Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the most common causes of neurological disability in young and middle-aged adults, with current prevalence rates estimated to be 30 per 100,000 populations. Women are approximately twice as susceptible as males, but males are more likely to have progressive disease. The onset of the disease normally occurs between 20 and 40 years of age, with a peak incidence during the late twenties and early thirties, resulting in many years of disability for a large proportion of patients, many of whom require wheelchairs and some nursing home or hospital care. The aim of this study is to update a previous review which considered the cost-effectiveness of disease-modifying drugs (DMDs), such as interferons and glatiramer acetate, with more up to date therapies, such as mitaxantrone hydrochloride and natalizumab in the treatment of MS. The development and availability of new agents has been accompanied by an increased optimism that treatment regimens for MS would be more effective; that the number, severity and duration of relapses would diminish; that disease progression would be delayed; and that disability accumulation would be reduced. However, doubts have been expressed about the effectiveness of these treatments, which has only served to compound the problems associated with endeavors to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of such interventions.

Multiple sclerosis: the context

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is believed to affect more than 1 million people worldwideCitation1 and is one of the most common causes of neurological disability in young and middle-aged adults.Citation2–Citation4 Prevalence rates vary considerably, though recent estimates put the global prevalence at any one time at 30 per 100,000 population,Citation5 with rates highest in northern parts of Europe, southern Australia and the middle part of North America. Women are approximately twice as susceptible as males,Citation2,Citation6,Citation7 but males are more likely to have progressive disease from onset.Citation8,Citation9 The onset of the disease normally occurs between 20 and 40 years of age, with a peak incidence during the late twenties and early thirties.Citation10,Citation11 The relatively early age of onset results in many years of disability for a large proportion of patients, many of whom require wheelchairs and some nursing home or hospital care.Citation12

While the cause and pathogenesis of MS are unknown, it is believed to be primarily an inflammatory condition in which autoimmune attack is associated with breakdown of the normal barrier separating blood from the brain. This leads to the destruction of myelin sheaths that normally facilitate nerve conduction. Although many episodes may be asymptomatic, the central nervous system has a limited capacity to repair areas of demyelination and repeated inflammatory attack often leads to scarring and loss of nerve cells themselves. It is the scarring and neuronal loss that probably underlie many of the chronic symptoms associated with MS, including limitation of mobility, ataxia, spasticity, pain, cognitive dysfunction and mood disturbance.Citation13 MS is a diverse disease initially characterized, in most cases, by recurrent attacks of neurological dysfunction (relapses) followed by periods of complete or incomplete recovery (remissions). If recovery from relapses is incomplete, there will be stepwise increases in disability. This is relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and accounts for between 65% and 85% of cases at onset.Citation13–Citation15 However, within 10 years about 50% develop the secondary progressive form of the disease, SPMS.Citation16 Approximately 15% of patients experience progressive MS from the outset with unrelenting advancement of the disease and maximum disability ensuing within months or over several years,Citation16 while a small proportion have a benign course with minimal disability after 10 to 15 years.Citation13 For those with RRMS, relapses occur unexpectedly, with symptoms appearing over a few hours and maximum recovery, although not necessarily complete, usually taking several weeks. Typically, relapses may involve visual disturbance (eg, blurred or double vision), sensory problems (numbness, tingling and pain), limb weakness or paralysis, or any combination of the above. On rare occasions, more serious relapses can occur involving life-threatening emergencies such as brain stem inflammation leading to total paralysis and respiratory failure.

The costFootnotea of multiple sclerosis

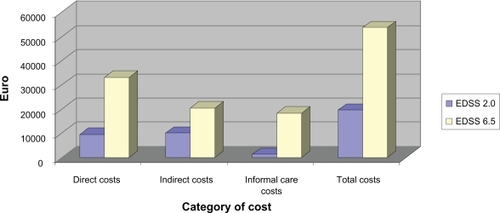

A number of studies have attempted to assess the costs of MS.Citation15,Citation17–Citation46 These have provided a wealth of information, but a variable picture emerges as to what constitutes the total cost of care. The full economic cost of MS is substantial, given that patients experience a major perturbation in their daily activities and the disease mainly affects young people, who are obliged to restrict their levels of economic activity, either temporarily or permanently.Citation16 A review of the literature demonstrated that positive relationships exist between some components of the direct costs of the disease and indirect costs – the largest element of the cost of the disease.Citation29 Studies have also shown that the total costs for patients increase with disability, as measured by the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS).Citation47 The EDSS scale is an instrument rating elements of neurological impairment, based upon an elaboration of the standard neurological examination. The scale ranges from 0 (no impairment) to 10 (death from MS).

A 2005 Swedish study by Kobelt et alCitation46 produced per patient total costs of €27,254 for mild MS (EDSS ≤ 2.0) and €52,457 for patients with severe MS (EDSS ≥ 6.5) (). This study represents one of the largest undertaken in terms of the number of patients included (n = 2048). The major direct cost driver in the UK was ambulatory care, which the authors put down to high DMD usage in the UK, thus increasing outpatient visits to neurologists. Indirect costs at EDSS ≤ 2.0 were calculated to be €10,142. However they double as disease severity increases to EDSS ≥ 6.5 (€20,545). This is mainly put down to the employment status of the patient (high levels of early retirement) which in turn increased the costs of informal care (EDSS ≥ 6.5 (€18,382).Citation46 Indirect costs tend to be the largest component of the overall cost burden in MS,Citation15,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22,Citation27,Citation31,Citation33–Citation46 due to patients having to leave the labor market because of their disability and carers also having to leave employment situations to provide the necessary support and care.Citation26 The question of whether the costs associated with informal care provided by friends and relatives should be included remains unclear, as they are difficult to quantify and value.Citation17 It is accepted that specific inputs to the care process provided by informal carers should be included in direct costs, but the issue of whether production losses resulting from such care inputs should be included remains contentious.

Figure 1 Costs (Euros) of multiple sclerosis by disease severity, UK 2005.

The impact of MS on quality of life has also received considerable attention. The most common symptoms associated with MS include motor weakness, spasticity, sensory impairment, ataxia, tremor, nystagmus, dysarthria, vision changes, depression, cognitive abnormalities, fatigue, and bowel, bladder and sexual dysfunction. In addition, patients may also experience secondary complications such as urinary tract infections, respiratory infections, decubiti and muscle contractures.Citation29 These primary and secondary symptoms result in people with MS suffering marked reductions in their quality of life (QOL), both during the early phases of the disease and as it increasingly impacts on levels of disability.Citation17,Citation48–Citation52 Relapses have a particularly devastating effect on patients lives, since relapses are unpredictable in terms of timing, duration and severity, and therefore restrict patients ability to plan their lives, especially for major events such as holidays and family celebrations.Citation52

While MS has an impact on all members of the family, the major responsibilities for care tends to rest with the primary carer – in most cases the spouse – who has to adopt other functions and responsibilities, including wage earner, homemaker, primary parent as well as carer.Citation53 The physical, mental and financial burdens placed on carers are often significant and can lead to stress, fatigue and depression and, in many cases, the quality of life of the carer reflects that of the patient.Citation54

The next section outlines the aim and objectives of this review and describes the approaches adopted in the collection and assessment of relevant studies.

Purpose of study and methods employed

The aim of this study is to examine the approaches used to assess the cost-effectiveness of disease modifying therapies in the treatment of MS such as interferons and glatiramer acetate, and to include recent additions to the formulary such as mitaxantrone hydrochloride (MH) and natalizumab in the treatment of MS. Electronic databases including Medline and Pubmed were searched for studies on the cost-effectiveness of interventions in the field of MS. Additional studies identified through searching bibliographies of related publications and using the Google internet search function. Included studies were assessed using standard critical appraisal criteria. Search terms were: Multiple Sclerosis, Disease management, Immunomodulatory drugs, Cost-Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness Analysis, Quality of life, Economic Evaluation, Cost Analysis, Cost benefit, Cost-utility, cost-utility analysis, Cost minimization, Pharmacoeconomics.

Inclusion criteria

Language of publication restricted to English.

Studies that focused on the diagnosis, prevention and or treatment of MS and reported a synthesis of associated costs and benefits.

Studies that compared treatment with immunomodulatory drugs; and used patient based outcomes such as relapses, disease progression, and side effects.

Studies restricted by date of conversion rates pre 1999.

Studies published in a peer reviewed journal.

Exclusion criteria

Non-English language publications

Abstracts presented at conferences

Studies not available in full text.

Studies were excluded if they did not conform, in the main, to the recognized conventions for health economic appraisals,Citation55 but some of these provided useful contextual information for this review.

The next section examines the range of available therapies available for the treatment of MS and provides an overview of the discussions relating to the relative effectiveness of such interventions.

The clinical effectiveness of treatments in MS

It has been argued that the management of patients with MS should begin at the time of diagnosis.Citation56 There are three aspects to the management of MS:Citation13

the prevention of disease progression and relapse rates;

the treatment of acute exacerbations;

the treatment of chronic symptoms.

Prior to the advent of disease-modifying drugs (DMDs), the mainstay of MS therapy was symptomatic treatment (both physical and pharmacological) and this still remains a central tenet of patient management in conjunction with disease-modifying therapy. Steroids are the treatment for acute exacerbations, but these do not affect consequent disability, while chronic symptoms are treated by physiotherapy and anti-spasticity drugs, and fatigue by psychological and physiological treatments and by neurorehabilitation.Citation13 Counseling is also important and may be given by health professionals or more informally through patient support groups and MS charities. However, the quality and scope of therapies and services available to sufferers of MS differ widely within countries and across countries.Citation32,Citation57

In relation to RRMS, the goals of treatment ideally are to:Citation12,Citation58,Citation59

treat acute relapses;

improve health-related quality of life;

reduce the frequency and severity of relapses;

delay disability accumulation; and

postpone the onset of the progressive phase of the disease.

The development and availability of DMDs was accompanied by an increased optimism that the above goals could be achieved, and these technologies have been approved by a number of regulatory authorities for use in the treatment of MS.

Evidence from randomized controlled trialsCitation60–Citation72 suggest that interferons, as a class, reduce both relapse rate and severity, and also delay the progression of disability especially in relapse remitting MS. There is also a marked and rapid reduction in MS disease activity, as measured by repeated brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.Citation12,Citation73 However, doubts have continued to be expressed about the validity of such evidence and the extent to which interferons are effectiveCitation3,Citation13 and the extent of their benefits relative to side effects and costs.Citation74 In addition to the clinical trials of interferons in MS, a number of reviews have aimed to assess the effectiveness of these therapeutic interventions,Citation3,Citation13,Citation58,Citation75–Citation83 but arriving at a consensus has been problematic due to the methodological quality of trials undertaken.Citation3,Citation79,Citation84,Citation85 It has been argued that “well conducted trials using outcome measures with clinical significance for groups of patients with different types of multiple sclerosis and long term follow up are needed if the evidence base of treatment for the disease is to be improved.”Citation85

Glatiramer acetate consists of a random mixture of four naturally occurring amino acids, which was initially developed to mimic myelin basic protein, one of the antigens thought to be involved in the pathogenesis of MS.Citation86 It has a different mechanism of action to that of the interferons and appears to have a more favorable tolerability profile,Citation59,Citation87 but has an efficacy profile broadly similar to that of the interferons.Citation87 In a review of its effectiveness, it was concluded that the extent of benefits were not clear,Citation13 while studies which have reported on the follow-up long term effects of glatiramer acetate,Citation87,Citation88 have also been confronted with methodological issues, which have tended to cloud the quality of these studies.Citation87 The 2008 REGARD studyCitation89 which compared the use of interferon beta-1a (IFNβ-1a) (Rebif®) and glatiramer acetate in patients with RRMS, found that with the outcome measure tested – time to first relapse – there was no significant difference between the two treatment groups. However, the authors acknowledged that “the ability to predict clinical superiority in a head to head study on the basis of results from separate placebo-controlled studies of each drug might be restricted and is challenged by a trial population with low disease activity”.

MH acts to “damage” rapidly dividing cells, such as those in the immune system and is usually used, in combination with other drugs, as a type of chemotherapy to treat certain types of cancer. In recent years it has also been used to treat very active RMSS or SPMS. During the period of treatment, mitoxantrone appears to work in MS by suppressing the immune system and giving the nervous system a chance to recover from recent relapses.Citation90 MH was licensed for the treatment of MS in October 2000 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but it is not licensed in some other countries for the treatment of MS and is used as an “off-licence” treatment for MS.Citation90 According to the MIMS study,Citation91 the high dose of MH (12 mg/m2 every 3 months for up to 24 months) was “effective and generally well tolerated, and significant treatment effects were found by all of the outcome measures”.Citation91 Although beneficial effects were also observed with the low-dose drug when compared to placebo, they were not as convincing as with the higher dose. The authors believed that “mitoxantrone provides a new therapeutic option for people with worsening relapsing remitting MS, or secondary progressive MS”.Citation91

Natalizumab is a monotherapy DMD approved for use by the FDA and the European Union (EU) in June 2006. It is one of the more recent additions for treatment in MS. It is thought that natalizumab exerts its therapeutic efficacy by blocking the pass of T cells, a specific immune cell which plays a major role in the pathogenesis of MS, through the blood–brain barrier, thus preventing these cells reach the central nervous system.Citation90 Natalizumab is currently licensed as a single disease modifying therapy for 2 subgroups of highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (HARRMS) sufferers and are classed as: “patients who have had 2 or more relapses with one or more gadolinium enhancing lesions on brain MRI or a significant increase in T2 lesion load compared with a recent MRI and patients who have failed to respond to a full and adequate course of inteferon b. Patients should have had at least one relapse in the previous year while on therapy, and have at least nine T2-hyperintense lesions in cranial MRI or at least one gadolinium-enhancing lesion.”Citation92 Results from the clinical effectiveness AFFIRM trialCitation93 are very favorable, with Natilizumab reducing the risk of sustained progression of disability by 42%, with the cumulative probability of progression being 17% compared to 29% in the placebo group. The rate of relapses was reduced by 68% and led to an 82% reduction in the accumulation of new or enlarged hyperintense lesions.Citation94 Natalizumab costs £1,130 (€1,167) per 300 mg vial, with an annual cost of approximately £14,730 (€15,214) per patientCitation95 (excluding hospital outpatient costs).

The result of this uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of these disease therapies in the treatment of MS has compounded the problems associated with endeavors to estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of such interventions.

The cost-effectiveness of DMDs in MS

In addition to the uncertainties associated with the clinical effectiveness, there are a number of issues that have resulted in a wide range of estimates of cost-effectiveness and hampered attempts to establish any consensus relating to the cost-effectiveness of DMDs. These issues relate to the appropriateness of the data used from the trials, the natural history or epidemiological data used to extrapolate to longer time horizons and the structure of models used. Methodological issues relating to the nature, derivation and quality of data used to populate the models and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria in terms of parameter selection can often render any estimations of cost-effectiveness less than robust.

While, increasing use has been made of Markov models, which allow for the management of patients in and between different health states over time, to assess the relative cost effectiveness of DMDs in MS, problems are still too readily apparent. The timescales involved frequently extend beyond the duration of clinical trials developed to assess clinical effects, and there is a lack of consensus as to the longer-term effects of DMDs. The wide range of estimates reflects the difficulties inherent in translating the results from clinical trials into models that assess the cost-effectiveness of interventions in MS, while the lack of homogeneity in study design also contributes to the wide variation in the estimates of cost-effectiveness and the difficulty of arriving at a consensus. Short-term analyses avoid the problems of attempting to extrapolate from clinical data, but fail to do justice to the duration of the illness and its progression over time, while longer-term studies may capture the longer-term effects, but do so with only limited evidence to substantiate the extrapolations from relatively short-term data and the assumptions underlying the construction of the models (for a full list of studies see ). For example, efficacy data from the EVIDENCE trialCitation66–Citation68 which lasted for 64 weeks was utilized in a model that simulated effects for a 4-year period. GuoCitation96 explained that the relatively short modeling timeframe was used to give consistency to “many US Payers realistic time horizon”, and also to maintain analytical relevance with the likelihood of newer IFNβ-1a treatments becoming available during the projected time span. Further, clinical trial data from the IFNβ-1b StudyCitation60,Citation64,Citation65 is utilized 9 times in various studies and, while, the trial lasted for 3 years, models have been developedCitation15,Citation97–Citation103 that cover timeframes of 10 years up to 40 years.

Table 1 Economic evaluations of disease modifying drugs in MS

However, recent studies have generally produced more favorable cost-effectiveness ratios, benefiting from more relevant and up-to-date data relating to disease progressionCitation15,Citation83,Citation92,Citation96,Citation98,Citation99,Citation102,Citation111,Citation113,Citation118 and it may be reasonable to conclude that the cost-effectiveness of interventions improves when longer time perspectives are employed, and the models more accurately reflect the progression of disease experienced by patients.Citation15,Citation96 As well as the time horizon, the estimates are highly sensitive to the approach taken to discounting costs and benefits; the cost of the therapies; the costs of patient management; disease progression, with and without treatment, and what happens to patients when they stop treatment; the impact of MS on carers in terms of utility loss and costs incurred; the effect of non-responders and adverse events associated with the therapies; the relationship between disability levels and utility losses and the extent to which indirect costs are included.

In addition, the assignment of utility scores to various “states” in MS have proved to be very contentious. These states are often founded on EDSS,Citation47 but concerns relating to its large inter-rater reliability, its ordinal nature and its unnecessary focus on certain categories of functional impairment have led to questions being posed regarding the validity of results derived from its use.Citation7,Citation104 The utility values attached to each of the EDSS states have varied considerably. It has been estimated that the difference between EDSS state 0 and 3.0 represents a 30% reduction in a patient’s quality of life, a similar reduction in quality of life from state 3.0 to state 7.0, while states 9.0 (helpless bed patient; can communicate and eat) and 9.5 (totally helpless bed patient; unable to communicate effectively or eat/swallow) have been valued at less than zero).Citation98 Variations in the utility scores associated with disease categories, the impact of relapses and the utility losses resulting, plus the speed of disease progression have all contributed to the difficulties involved in estimating the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) losses for a patient suffering with MS.

Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis by drug

This paper focuses on recent additions to the literature and develops the base established in a previous review,Citation105 but in order to provide a suitable context, a brief discussion of “older” studies and their limitations is presented below.

The perspective employed in the studies had a major effect on the cost-effectiveness ratios. For example, Brown et alCitation97 examined the cost-effectiveness (CE) of IFNβ-1b in slowing disability progression in patients with RRMS. The model was designed to estimate costs and outcomes for cohorts of 1000 females and 1000 males followed 40 years from onset, with the primary health outcome being cost per disability year avoided (DYA). Results showed that over the natural history of RRMS, females were expected to achieve 10.5% fewer disability years (9% after discounting at 5%). The cost per DYA was relatively high with CAN$189,230 (US$124,892), and increasing to CAN$274,842 (US$181,395) after discounting at 5%, with the authors recognizing that the cost perspective they adopted was “relatively narrow” as they only included direct costs and no indirect costs. The 2002 study by NuijtenCitation15 used clinical dataCitation64 to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of both IFNβ-1a and IFNβ-1b in the treatment of MS versus standard care. A Markov model was designed containing 4 mutually exclusive Markov states corresponding to 4 EDSS severity points and the incremental cost-effectiveness was measured by cost per QALY. Total per patient costs (discounted at 6%) for IFNβ arm was £221,436 (US$364,993) versus £51,214 (US$84,416) for the no treatment (standard care) group. The higher costs for the IFNβ arm derived from the cost of IFN ((£179,367) (US$295,651)). The average QALY gained was estimated at 28.2 versus 24.9 for the standard care group, a gain of 3.3 QALYs. The authors conclude that using IFN as preventative treatment “may not be fully justified from a health-economic perspective”, but they acknowledge that it is “associated with an improved effectiveness compared with no preventative treatment.”

Parkin et alCitation100 evaluated the cost-effectiveness of IFNβ-1b in patients with RRMS. The clinical data was taken from 2 trials by the IFBN Multiple Sclerosis Study GroupCitation60,Citation64 with patient, cost and quality of life data collected from questionnaires administered (EQ-5D and MSQOL). When discounted at 6%, IFNβ-1b was shown to reduce relapse by 1.52 per patient (over 5 years) giving a cost-effectiveness ratio of £28,700 (US$44,428) per relapse avoided. With a QALY gain of 0.054, this gave a cost-utility ratio of £809,900 (US$1,253,725) per QALY gained. Allowing for effects of progression over 5 years, the QALY gained reduces to £328,300 (US$508,208). Parkin’s studyCitation100 cited the lack of severe EDSS scores and no indirect costs as limitations of the study. However, new EDSS states were added in for the 1999 updateCitation107 to give a “range of different EDSS levels”. In this update,Citation107 new data were also collected for costs and QOL with the patients split into two groups: patients who had suffered a relapse in the last 6 months and those who had not. A decision analytic model was then constructed using EDSS health states to calculate both the cost-effectiveness and cost-utility. The authors concluded that IFNβ-1b produces short-term QOL gains in patients with RRMS, however, the QALY gains are small and thus “the benefits are achieved only with a large additional cost”.

Studies that employed a societal perspective have, on occasions, produced more favorable cost-effectiveness ratios. For example, Forbes et al’s 1999 studyCitation74 evaluated the cost-utility of IFNβ-1b in SPMS in 132 ambulatory patients studied from a healthcare sector perspective but employed a societal perspective in the sensitivity analysis. The cost per QALY gained, from a healthcare perspective was estimated to be £1,024,393 (US$1,602,509) with a 95% confidence interval of £276,191 (US$432,059) to £1,484,824 (US$2,322,784). From a societal perspective, the authors claim the cost per QALY gained reduced by “only 0.2%” to around £1,022,344 (US$1,679,507). The authors concluded that it was “probably appropriate to allocate more resources to people with secondary multiple sclerosis, but access to IFNβ-1b should be restricted.”Kendrick et al’s 2000 studyCitation106 examined the CE of long term IFNβ-1a, and set out to challenge the assumptions of the clinical and cost benefit of IFNβ-1a used in previous CE studies. The model estimated the rate of disability progression in the RRMS patients receiving either IFNβ-1a or standard care (ie, without DMDs) and was extrapolated to produce annual EDSS scores for a period of 20 years. Results of the model showed high disease progression within the placebo arm (progression to EDSS stage II by 4 years from start of study) compared to patients receiving IFNβ-1a (progression to stage II by 11 years) Further extrapolation showed the same sets of patients progressing to stage III by 9 and 20 years respectively. Total costs per QALY (discounted at 6%) ranged from £27,000 (US$42,237) to £38,000 (US$59,445) depending on the length of IFNβ-1a treatment. Once societal costs (all costs including both direct and indirect) were included in the model, it was claimed that treatment of RRMS with IFNβ-1a could provide “substantial” cost savings to society, increasing with treatment duration. Phillips et alCitation102 cited the similar assumptions and lack of ability to “closely reflect clinical practice” in the study. However, this study, which followed Parkin’sCitation100 data and model closely, also considered the impact on indirect costs in the analysis to obtain a wider societal perspective and arrived at a more favorable cost-effectiveness ratio.

The next section summarizes and discusses more recent studies grouped by the disease modifying therapy.

Interferon

A US study by Guo et alCitation96 examined the clinical and economic effectiveness of the treatment of RRMS using high-dose/high frequency subcutaneous (SC) IFNβ-1a, compared with low-dose weekly intramuscular (IM) IFNβ-1a. The study was performed from the US Payer’s perspective with a discrete event simulation model (DES) populated with data mainly taken from the EVIDENCE trial.Citation66–Citation68 The use of the DES model, over the more commonly used Markov model, was designed to utilise its flexibility when comparing various treatment scenarios, with the authors arguing that a Markov model “forces a disease into a few mutually exclusive states within a fixed time”, eg, fixed EDSS stages. The model simulated 1000 pairs of patients over a 4 year timeframe. Discounting was calculated annually at 3% beyond the first year. The total mean costs per patient (discounted) were US$79,890 (€67,477) with SC IFNβ-1a, compared with US$74,485 (€62,912) with IM IFNβ-1a. However, even though this means an increase of US$5405 (€4,565) per patient, SC IFNβ-1a was estimated to save 23 relapse-free days per patient – an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of US$10,755 (€9,084) per relapse prevented and US$ 232 (€196) per relapse-free day prevented. The authors estimated that there was a 95% probability that the cost per relapse prevented would be below US$20,000 and the cost per relapse-free day would be below US$420. They concluded that based on 1000 replications of the 1000 pairs of patients from the EVIDENCE trial, SC IFNβ-1a would have greater health benefits over 4 years than IM IFNβ-1a. However, this study had a limited time duration and did not include indirect costs in the analysis. Further, the cost-effectiveness was measured in relation to relapses prevented and relapse-free days and therefore make it difficult to gauge the relative cost-effectiveness compared with other products.

Iskedjian et al’s 2005 Canadian studyCitation108 estimated the cost-effectiveness of Avonex® (IFNβ-1a) compared with current treatment of clinically definite multiple sclerosis (CDMS) following a single demyelinating event (SDE). The study performed both a cost-effectiveness (CEA) and cost-utility analysis (CUA) from the societal and healthcare sector perspectives. A Markov model was designed to generate the time spent in the pre-CDMS state (monosymptomatic life years (MLY)) and quality adjusted monosymptomatic life years gained (QAMLY) for the CEA and CUA perspectives respectively. Clinical data on the progression to CDMS was derived from the CHAMPS studyCitation69 and a 1989 Canadian study.Citation8 Costs were derived from two Canadian cost of illness (COI) studies.Citation26,Citation109 The time horizon was set at 12 years by doubling the projected median time (6 years) a patient on Avonex would progress to the CDMS state. This enabled the authors to analyze the outcomes of the majority of the patients who suffered an SDE. The time horizon for the CUA model was 15 years. This was the median time for progression to CDMS state (6 years) added to the median time of progression to EDDS 3 (approx 7 years). Outcomes at 20 and 30 years were captured through sensitivity analysis. From the Ministry of Health (MoH) perspective, the incremental cost-effectiveness of Avonex per MLY gained was CAN$53,110 (€37,658). In the CUA, the cost per QAMLY gained was CAN$227,586 (€161,371). From the societal perspective, the CEA ratio was CAN$44,789 (€31,758) per MLY gained and CAN$189,286 (€134,214) per QAMLY gained. The results of this study are favorable towards both the clinical and cost-effectiveness of Avonex for patients experiencing an SDE. Additionally the authors suggest that the overall incremental cost-effectiveness of Avonex increases if treatment is administered pre-CDMS.

Kobelt et al’s 2003 studyCitation99 employed a Markov model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of IFNβ-1b treatment in patients with RRMS or SPMS. The study aimed to address how “treatment affects disease progression from diagnosis to severe disability”. Using clinical data from two 5-year trials,Citation64,Citation70 natural history dataCitation8 and cost-utility data,Citation17 Kobelt’s study was performed from both the healthcare sector and societal perspective in Sweden. The model used the EDSS scale to define disease parameters and captures a mix of patients with both RRMS and SPMS according to the level of exacerbations suffered. The model consisted of 40 cycles (10 years) that is four 3-month cycles per year, with the IFNβ-1b intervention lasting 12 cycles (3 years) discounted at 3%. Mean total costs in the placebo arm amounted to €399,200 with the intervention €400,700. Cost per QALY gained was €7,800 (after 12 cycles). However, QALY gained increased to €38,700 with IFNβ-1b when treatment was increased to 54 months, and with potential cost savings being evident in the more severe states for the same time scale. At a willingness to pay (WTP) threshold of €50,000, the probability that IFNβ-1b was cost-effective was around 80%, which would increase to 90% at a WTP threshold of €80,000. The sample contains an SPMS subgroup combined with an RRMS subgroup from a differing trial as the authors had selected these due to their disease progression, rather than on relapse rate. Therefore the analysis supported the authors’ hypothesis that there is a larger treatment effect the more active the disease. Kobelt’s study claimed that the combination of RRMS and SPMS patients from two separate studiesCitation8,Citation64,Citation65 might result in a population of two groups that “were not fully comparable”. The issue of non-compliance in the clinical trials was also highlighted as a factor that might artificially improve the cost-effectiveness – a problem also seen in other studies.Citation92,Citation103

Kobelt et al’s 2000 studyCitation110 estimated the cost-effectiveness of treatment of SPMS with IFNβ-1b. Using data from a population-based observational study,Citation17 a Markov model was developed to estimate the incremental cost per QALY for treatment with IFNβ-1b compared with no treatment. Taking a Swedish societal perspective, the model was based on a 10 year time horizon (in cycles of 3 months) with Markov states based on EDSS measurements. The mean total cost of a relapse was estimated to be SEK 25,700 (€2,714). For the base case, the incremental QALY gain over 10 years was SEK 55,500 (€5,862) resulting in a cost per QALY of SEK 342,700 (€36,194) (including all costs). When indirect costs were excluded, the cost per QALY increased to SEK 542,000 (€57,243). Employing a cost-effectiveness threshold of US$60,000 (€51,418), the vast majority of cost-utility ratios were either below or equal the threshold.

Kobelt’s 2002 studyCitation111 used an adapted version of the Markov model described above, populated with natural history data of MS based on the London, Ontario study.Citation8 The inclusion of these data was to reflect more accurately disease progression rather than using progression rates from clinical trial data which could result in potential bias. The model had 6 disease progression steps as opposed to the seven the earlier model. Using the same Swedish cost data,Citation17 and discounting at 3%, this cost-utility analysis produced cost of care savings of SEK 177,400 (€18,736), of which SEK 11,600 (€1,225) were due to relapse reduction. When all costs (including indirect costs) were included, the potential savings were SEK 150,300 (€15,874). The QALY was also estimated at SEK 257,200 (27,164) in the base case. The authors attributed the higher cost-utility ratio of SEK 542,000 (€57,243) compared with the previous study to “the underestimate of the progression of disability”. The study concluded that the cost per QALY falls below the threshold of US$30,000 (€25,709) “that in previous studies has been accepted as cost-effective in Sweden”.

Lazzaro et al’s 2009 studyCitation112 is the most recent economic evaluation of IFNβ-1b in the treatment of MS, the cost of treatment of IFNβ-1b from the diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) was compared to the cost of treatment once conversion to clinically definite MS (CDMS) has happened, from the Italian healthcare sector and societal perspectives. The study incorporated the patients enrolled in the BENEFIT studyCitation71 into a 25-year epidemiological model. From the healthcare sector perspective, the annual IFNβ-1b treatment costs per patient amounted to €7,150, €19,105 and €32,767 for the CIS, RRMS and SPMS patients respectively. IFNβ-1b was the major cost driver for CIS patients, with hospital admissions being the largest cost component for RRMS and SPMS patients. Conversely, from the societal perspective, the annual cost of treatment rose to €7,307, €25,349 and €45,841 for the CIS, RRMS and SPMS patients respectively. The cost drivers for the CIS patients were again the cost of IFNβ-1b. However, the major cost drivers for both the RRMS and SPMS patients were loss of working days combined with patient and family resources. The QALYs gained achieved statistical significance (P < 0.0001) with 7.84 QALYs gained for the CIS arm, compared to 7.49 for the untreated arm. The authors concluded that early treatment of IFNβ-1b was cost-effective from the health-care sector point of view with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of €2,575 falling well below the unofficial acceptable incremental QALY range of between €12,000 and €60,000. The study also suggested that early treatment of CIS with IFNβ-1b would significantly reduce disease progression to CDMS thus making it cost-effective in the long term.

A 2003 study by Lepen et alCitation113 used econometric modeling of the 4 year data from the PRISMS studyCitation72 and, using the area under the EDSS-time curve (AUC-EDSS) as an integrated measure of disability, calculated the effectiveness of IFNβ-1a as number of EDSS-months of disability saved. By projecting the data over 10 and 20 years, the authors hypothesized that because the model would produce “real cost-effectiveness results in terms of cost per EDSS month of disability prevented”, it may be more “valid and more clinically meaningful than cost-utility ratios”. Cost data was derived from Murphy et al’s 1998 cost of illness study.Citation21 The model reported that after 10 years, the IFNβ-1a arm experienced 484 EDSS-months of disability compared to 605 for the placebo arm. For 20 years, these figures increased to 1266 and 1587 respectively. For the UK, the total cost of care (including standard care and IFNβ-1a treatment was) £243,141 (€389,711) for 10 years. This gave a cost per EDSS-month saved of £453 (€726). At 20 years, the total costs rose to £448,602 (€719,029) with the cost per EDSS-month saved reducing to £222 (€356). The authors concluded that maintaining the patient at their current EDSS level reflected the increasing economic benefit of IFNβ-1a. Secondary analysis in the study confirmed that using a one dose of 44 μg rather than three doses of 22 μg per week saved 15 EDSS-months over 10 years, giving a cost of £14,000 (€22,440) per EDSS-month saved. However, the authors acknowledged the limitation of using the AUC measure as “a patient with a period of improvement followed by deterioration might have the same AUC as one who showed deterioration followed by improvement”. This, the authors add, may lead to “erroneous disability projections” if modeled over 20 years.

Glatiramer acetate

In 2001, Bose et alCitation114 estimated the cost-effectiveness of glatiramer acetate in the treatment of RRMS using clinical data from the pivotal clinical trial for Copaxone®Citation88,Citation115 combined with published cost and natural history data. The EDSS states used ranged from 0 to 7. The perspective was from the healthcare sector so no indirect costs were included. The cost per relapse, calculated from Parkin,Citation100 was £2,362 (€3,786). Base case estimates for both 6 and 8 years demonstrated that cost-effectiveness improved as the time horizon lengthens with £13,626 (€21,840) and £11,000 (€17,631) cost per relapse avoided respectively. Cost per disability unit avoided was estimated at £11,935 (€19,130) and £8,862 (€14,204) for 6 and 8 years respectively. When the duration of a relapse was one month instead of two, the cost per QALY over 8 years was £64,636 (€103,600). Further, after discounting at 6%, the cost per relapse avoided was £12,092 (€19,381), with cost per QALY being £24,870 (€39,862). Differential discounting (6% on costs and 1.5% on benefits) resulted in the cost per relapse at 8 years being £10,184 (€16,323) and cost per QALY £20,929 (€33,545). Finally, when indirect and informal costs were added (by doubling the cost per relapse to £4,724 (€7,572)) the cost per relapse avoided declined from £11,000 (€17,631) to £8,632 (€13,836), and cost per QALY declined to £17,733 (€28,423) in the base case. However, in terms of the cost-effectiveness of glatiramar acetate, Bose used natural history data to fill in a gap where clinical data was not available for the placebo arm patients beyond 35 months. Finally, in terms of the cost per QALY ratio being driven by utility loss associated with relapse, the authors conclude that analysis “would have been improved with more robust data”.

Natalizumab

The study by Gani et alCitation92 examined the cost-effectiveness of natalizumab (Tysabri) compared with IFNβ, glatiramer acetate and best supportive care in patients with highly active RRMS (HARRMS). Using previously published data, including efficacy data from the AFFIRM study,Citation93 a 30-year model was developed from a societal perspective, based on a previous study by Chilcott.Citation98 Of the 3 disease modifying treatments, natalizumab resulted in the most cost-effective ICER of £2,300 (€3,348) per QALY gained, compared with IFNβ’s ICER of £2,000 (€2,911) and glatiramer acetate’s ICER of £8,200 (€11,937) per QALY gained. Sensitivity analysis showed that the cost-effectiveness of natalizumab reduced when the timeline horizon was reduced to 20 years. When viewed from the healthcare sector perspective, the cost-effectiveness also fell. With a WTP threshold set at £30,000 (€43,671) per QALY, the probability of natalizumab being cost-effective was 89%, 90% and 94% respectively compared to IFNβ-1b, glatiramer acetate and best supportive care (BSC) respectively. In conclusion, the authors suggested that natalizumab for patients with HARRMS was more cost-effective than IFNβ, glatiramer acetate and best supportive care if the societal WTP was higher than £8,200 (€11,937) per QALY or £26,000 (€37,849) per QALY from the healthcare sector perspective. However, the authors acknowledged the limitations linked to the combining of RRMS and SPMS patients from the AFFIRM studyCitation93 and the London Ontario dataset,Citation8 while they did not include all indirect costs and also experienced the same uncertainty as KobeltCitation94 when considering non compliance.

Kobelt et al’s 2008 studyCitation94 modeled the cost-effectiveness of natalizumab compared with current practice. Employing a Swedish healthcare sector and societal perspective, Kobelt’s study used existing literature – AFFIRM,Citation93 Ontario data setCitation8 and cost data from 2 previous Swedish studiesCitation116,Citation117 – and developed a model that covered a 20-year time frame with effects and costs discounted at 3%. The total cost of natilizamub was €609,850, €3,830 less than standard care, with a cost per QALY dominating, thus representing a best case scenario. The cost of natalizumab was €352,175 with a cost per QALY of €38,000, from the healthcare sector perspective. From the societal perspective, natalizumab was dominat in 55% of cases and the probability that the cost per QALY was < €50,000 was 75%. The authors concluded that for the population data used and from a societal perspective, “natalizumab provides an additional health benefit at a similar cost to current DMDs”.

Both these studies suffered from uncertainties, while Kobelt et al also expressed concern that all the RRMS patients started at EDSS 3.5. Additionally, the open-label extension of the AFFIRM study was stopped due to the appearance of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in 2 patients, all of which resulted in Kobelt et al concluding that the “analysis has to be treated with caution”.

Thus even with newer therapies the uncertainties relating to their respective uncertainties remain.

Comparison studies of disease modifying therapies

Interferon and glatiramer acetate

Bell et al’s 2007 studyCitation118 compared the cost-effectiveness of 4 immunomodulatory drugs: SC glatiramer acetate and 3 IFNβs: IM IFNβ-1a, SC IFNβ-1a and SC IFNβ-1b. A Markov model populated by data from the literature was developed to assess the cost-effectiveness of 5 treatment strategies for RRMS patients compared to symptom management alone. The model incorporated the EDSS scale with 7 specific transition health states with the time horizon set at 13 years (approximation of a patient’s lifetime with MS) and was measured from the US societal perspective. Total costs for the lifetime of a patient were calculated at US$295,586 (€217,919) for symptom management arm and US$352,760 (€260,071), US$364,267 (€268,554), US$377,996 (€278,676) and US$358,509 (€264,309) for each drug arm respectively. When direct medical costs were compared, the additional costs of drug treatment were partially offset by cost savings in MS related medical costs. The SC glatiramer acetate arm had the largest cost offset with 24% saved compared to 17% to 22% cost saved by beta IFNs. Overall, the SC glatiramer acetate patients received greater cost benefits with the incremental cost per QALY of US$258,465 (€190,552) compared to US$337,968 (€249,165), US$416,301 (€306,916) and US$310,691 (€229,056) for the 3 IFNβ treatments respectively. The authors concluded that all 4 drug treatments were associated with increased benefits for RRMS patients compared to symptom treatment alone, with SC glatiramer acetate being best strategy.

Prosser et alCitation103 compared the cost-effectiveness of 3 immunomodulatory drugs (IFNβ-1a, IFNβ-1b and glatiramer acetate) for newly diagnosed non-PPMS, compared with no treatment. A state transition model was developed with a 10-year treatment duration from the societal perspective. Costs were discounted at 3% per year. From base case analysis, IFNβ-1a provided more health benefits and resulted in an ICER of US$1,838,000 (€1,575,088)/QALY for men and US$2,218,000 (€1,900,732)/QALY for women. With 10-year treatment of IFNβ-1a, this resulted in gains of 11 QALYs for men and 13 for women. IFNβ-1b proved to be less effective and more costly than the no treatment. Glatiramer acetate had a higher ICER, but lower cost compared to IFNβ-1b. When treatment duration was varied to 40 years, the ICER for IFNβ-1a decreased to US$250,000 (€214,239)/QALY for women and US$235,000 (€201,385)/QALY for men.

This study demonstrated the significance of treatment duration on the relative cost-effectiveness of the therapies. “No treatment” for treatment duration of ≤6 years was found to be the most clinically and cost-effective option as treatments associated with side effects “outweighed the benefits of treatment”. Glatiramer acetate was found to be the most effective treatment between 6 and 9 years duration, whilst treatment of IFNβ-1a was found to be most effective for 10 years or more. The authors concluded that IFNβ-1a was the “best strategy in terms of health outcome”. However, the study suffered from assumptions made due to lack of information on the age at onset, relapse frequency or type of symptoms at onset of disease presented major limitations which the authors argued could affect the favorability of cost-effectiveness ratios.

In an evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of 4 DMDs in the treatment of RRMS and SPMS,Citation98 3 IFNβs and glatiramer acetate were compared to no treatment in a 20-year model, with cost per QALY being the main outcome measure. Using data from the literature, the model simulated the clinical course of MS by using 10 point EDSS health states (RRMS from point 0 to 10; SPMS from point 2 to 10). IFNβ-1a 6 MIU/week (Avonex) proved to be the most cost-effective at £42,041 (€67,384) per QALY gained. The least cost-effective was glatiramer acetate with 20 mg/week (Copaxone) at £97,636 [€156,493]) per QALY gained. The probability that any of the interventions would be less than a WTP threshold of £20,000 (€32,056) was between 3% and 18%. Due to the uncertainty surrounding the point estimates of cost-effectiveness, the authors suggested further research to establish the actual benefit derived from the treatment – specifically delays in relation to disease progression. The authors also recommended “real data” on the progress of people once treatment has ceased.

Interferon and mitoxantrone

Touchette et alCitation119 aimed to compare the cost-utility of IV MH and SC IFNβ-1b with routine supportive care in patients with progressive relapsing MS (PRMS) and SPMS. The IV MH was administered every 3 months compared to the IFN, which was administered every other day. A Markov model was populated using EDSS level 3 as an entering point (using existing published data including the MIMS study,Citation91 EUSPMS studyCitation63 and utility measures from Parkin).Citation100 Patients’ disease progression was followed for 10 years and the study was undertaken from both the insurer’s and societal perspectives, with data gathered from Olmsted County (MMSDPC study).Citation120 IV MH resulted in 5.0860 QALYS costing US$53,378 (€53,007), compared with routine supportive care (4.9650 QALYS over 10-years costing US$46,331 (€46,009)). IFN produced a QALY of 5.17 with a cost estimate of US$115,833 (€115,028). From a societal perspective, IV MH was US$378,464 (€375,833) with IFN remaining the most costly at US$433,932 (€430,916). When compared with routine supportive care, the IV MH resulted in a cost-utility ratio of US$58,272 (€57,867) per QALY, and from the societal perspective, IV MH was less costly and produced larger QALY gains.

The cost-utility ratios for IFN were higher from both the insurer and societal perspective (US$338,738 (€336,383) and US$245,700 (€243,992) respectively, compared to routine care. The mean cost-utility ratio for IFNβ-1b relative to MH was US$741,044 (95% CIs: –US$6,564,807, US$7,482,341) and likely to be less than US$100,000 on less than 1% of occasions. The authors concluded that from the insurers’ perspective, IV MH in patients with PRMS and SPMS with EDSS scores of between 3 and 6 was a cost-effective option. From a societal perspective it represented a cost saving. Conversely, IFN treatment was not seen to be cost-effective in the population with the results being sensitive to both the clinical and cost-effectiveness of IV MH. However, the analysis suffers from the same limitations as those in Parkin’s studyCitation100 with regard to the use of utility measures.

Discussion and conclusion

The evaluation of DMDs for the treatment of MS provides an excellent scenario for illustrating the complexities involved in attempting to integrate the evidence relating to effectiveness and resource utilization. A number of useful frameworks and matrices have been proposed. For example, interventions with cost-QALY ratios of between $4,839 (€5,562) and $32,258 (€37,078) were adjudged to be cost-effective when there was good clinical evidence of their effectiveness,Citation121 while this has been adapted more recently as an aide for decision-makers.Citation122 Another issue is what actually is a reasonable indicator of cost-effectiveness? It has been argued, for example, that NICE is more likely to view a technology favorably, subject to other relevant factors, if it costs less that $48,387 (€55,617) per QALY,Citation123 while the risk sharing scheme for MS treatments has a threshold of $58,065 (€66,741) per QALY.Citation124 Other studies have suggested that a cost per QALY threshold of $50,000 (€57,471) is appropriate,Citation125,Citation126 while a survey of health economists has suggested a threshold of $60,000 (€68,966).Citation110

The papers discussed in this review represent the wealth of information available to decision makers in relation to DMDs in the treatment of MS. However, all papers have limitations associated with them, which mean that the conclusions derived from a review of cost-effectiveness studies of DMDs remain equivocal. Issues relating to model design,Citation15,Citation100,Citation101,Citation107,Citation113 use of natural history data and, reliance on clinical data that are subject to a variety of interpretations have been common features of studies undertaken to date and have conspired to generate an evidence-base that is at best muddled and inconclusive .

Recent studies have benefited from more relevant and up-to-date data relating to disease progressionCitation15,Citation83,Citation92,Citation96,Citation98,Citation99,Citation102,Citation111,Citation113,Citation118 and have generally produced more favorable cost-effectiveness ratios, which are reflected in the cost-effectiveness acceptability curves produced. It therefore may be reasonable to conclude that the cost-effectiveness of interventions improves when longer time perspectives are employed, and the models reflect the progression of disease experienced by patients.Citation15,Citation96 As well as the time horizon, the estimates are highly sensitive to the approach taken to discounting costs and benefits; the cost of the therapies; the costs of patient management; disease progression, with and without treatment, and what happens to patients when they stop treatment; the impact of MS on carers in terms of utility loss and costs incurred; the effect of non-responders and adverse events associated with the therapies; the relationship between disability levels and utility losses and the extent to which indirect costs are included.

In conclusion, it would appear that the balance of evidence suggests that DMDs for patients with MS are not cost-effective when measured against prevailing cost/QALY thresholds. However, more recent studies have tended to tilt this balance and demonstrated a trend in producing lower cost-effectiveness ratios, which are either within thresholds or are reasonably close to them. Further, the use of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves in more recent studies has also served to highlight the likelihood that DMDs can be viewed as representing value for money. As more appropriate, robust information becomes available over the lifetime of the disease and as greater numbers of patient histories become documented, it is to be hoped that the quantity and quality of evidence on the impact of the drugs on disease progression clarifies issues relating to the effectiveness of the treatments, which, in turn, can lead to more informed judgement to place alongside the evidence-base in relation to decision making.

In addition, there are currently several major trials looking at the efficacy of new DMDs such as alemtuzumab (Phase III), Fingolimod (Phase III), cladribine (Phase III) and the controversial cannabinoid Sativex (Phase I). Therefore, it seems timely that developments in the field of health economics will hopefully address the methodological difficulties associated with modeling disease progression in order to move towards a consensus relating to the extent to which DMDs in the treatment of patients with MS can be regarded as being cost-effective.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

a Currencies have been reported in Euros and the specific currency used in the study. Conversion of currencies was calculated for the 1 January of the currency rate year stated by the author. Every effort has been made to maintain the accuracy and integrity of the original estimate.

References

- DeanGHow many people in the world have multiple sclerosis?Neuroepidemiology199413178190200

- HauserSLMultiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseasesIsselbacherKJBraunwaldEWilsonJDHarrisons’s Principles of Internal MedicineNew YorkMcGraw-Hill1994

- NoseworthyJHLucchinettiCRodriguezMWeinshenkerBGMedical progress: multiple sclerosisN Eng J Med2000343938952

- FieschiCPozzilliCBastianelloSHuman recombinant interferon beta in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: preliminary observationsMultiple Sclerosis19951S28S319345395

- http://www.mssociety.org.uk/news_events/news/press_releases/atlas.html. Accessed June 2009.

- http://www.nationalmssociety.org/Sourcebook-Epidemiology.asp. Accessed 25 March 2003.

- RichardsRGSampsonFCBeardSMTappendenPA review of the natural history and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis: implications for resource allocation and health economic models. [abstract]Health Technol Assess2002617312022938

- WeinshenkerBBassBRiceGPNoseworthyJThe natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically-based study. I. Clinical course and disabilityBrain19891121331462917275

- WeinshenkerBBassBRiceGPNoseworthyJThe natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically-based study. II. Predictive value of the early clinical courseBrain19891121141911428

- RieumontMJDelucaSANeuroimaging evaluation in multiple sclerosisAm Fam Physician1993482732768342480

- HibberdPLThe use and misuse of statistics for epidemiological studies of multiple sclerosisAnn Neurol199436S218S2307998791

- Lyseng-WilliamsonKAPloskerGLManagement of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: defining the role of subcutaneous recombinant interferon-b-1a (Rebifâ)Dis Manage Health Outcomes200210307325

- CleggABryantJMilneRDisease-modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis: a rapid and systematic reviewHealth Technol Assess.20004iiv1101

- FrancisDAThe current therapy of multiple sclerosisJ Clin Pharm Ther19931877848458884

- NuijtenMJCHuttonJCost-effectiveness analysis of interferon beta in multiple sclerosis: a Markov process analysisValue Health20025445411873383

- GoodkinDEInterferon beta therapy for multiple sclerosisLancet1998352148614879820292

- HenrikssonFFredriksonSMastermanTJönssonBCosts, quality of life and disease severity in multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study in SwedenEur J Neurol20008273511509078

- O’BrienBMultiple SclerosisLondon, UKOffice of Health Economics1987

- HolmesJMadgwickTBatesDThe cost of multiple sclerosisBr J Med Econ19958181193

- HenrikssonFJönssonBThe economic cost of multiple sclerosis in Sweden in 1994Pharmacoeconomics19981359760617165326

- MurphyNConfavreuxCHasJEconomic evaluation of multiple sclerosis in the UK, Germany and FrancePharmacoeconomics19981360762217165327

- Whetten-GoldsteinKSloanFGoldsteinLKulasEA comprehensive assessment of the cost of multiple sclerosis in the United StatesMultiple Sclerosis199844194259839302

- KobeltGLindgrenPSmalaACosts and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. An observational study in GermanyHEPAC200126068

- KobeltGLindgrenPParkinDCosts and quality of life in multiple sclerosis. A cross-sectional observational study in the United KingdomStockholmStockholm School of Economics EFI Research Report No. 398, 2000

- AscheCVHoEChanBEconomic consequences of multiple sclerosis for CanadiansActa Neurol Scand1997952682749188900

- The Canadian Burden of Illness Study groupBurden of illness of multiple sclerosis: Part I – cost of illnessCan J Neurol Sci19982523309532277

- AmatoMPBattagliaMACaputoDThe costs of multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional, multicenter cost-of-illness study in ItalyJ Neurol200224915216311985380

- TissotEWoronoff-LemsiMCMultiple sclerosis: cost of the illnessRev Neurol (Paris)20011571169117411787352

- GrudzinskiANHakimZCoxERBootmanJLThe economics of multiple sclerosis. Distribution of costs and relationship to disease severityPharmacoeconomics19991522924010537431

- MidgardRRiiseTNylandHImpairment, disability, and handicap in multiple sclerosis. A cross-sectional study in an incident cohort in More and Romsdal County, NorwayJ Neurol19962433373448965107

- RieckmannPEarly multiple sclerosis therapy in the effects of public health economicsMed Klin200196Suppl 11721

- MiltenburgerCKobeltGQuality of life and cost of multiple sclerosisClin Neurol Neurosurg200210427227512127667

- PugliattiMRosatiGCartonHThe epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in EuropeEur J Neurol20061370072216834700

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPCosts and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in The NetherlandsEur J Health Econ20067556416416135

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPBattagliaMLucioniCUccelliACosts and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in ItalyEur J Health Econ200674554

- McCronePHeslinMKnappMBullPThompsonAMultiple Sclerosis in the UK: service use, costs, quality of life and disabilityPharmacoeconomics20082684786018793032

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPCosts and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in GermanyEur J Health Econ200673444

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPGerfinALutzJCosts and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in SwitzerlandEur J Health Econ200678695

- RotsteinZHazanRBarakYAchironAPerspectives in multiple sclerosis health care: special focus on the costs of multiple sclerosis20065511516

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPKerriganJRussellNNixonRCosts and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in the United KingdomEur J Health Econ2006796104

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPCosts and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in SpainEur J Health Econ200676574

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPCosts and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in AustriaEur J Health Econ200671423

- KobeltGBergJAtherleyDJönssonB Costs and Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis A Cross-Sectional Study in the USA Stockholm School of Economics in its series Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance with number 594; 2004.

- KobeltGCosts and quality of life for patients with multiple sclerosis in BelgiumEur J Health Econ200672433

- KobeltGPugliattiMCost of multiple sclerosis in EuropeEur J Neurol2005Suppl 12636715877782

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPFredriksonSJönssonBCosts and quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis in EuropeJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20067791892616690691

- KurtzkeJFRating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS)Neurology198333144414526685237

- MurphyNConfavreuxCHaasJKönigNRoulletEQuality of life in multiple sclerosis in France, Germany and the United KingdomJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1998654604669771766

- The Canadian Burden of Illness Study GroupBurden of illness of multiple sclerosis: Part II: Quality of LifeCan J Neurol Sci19982531389532278

- SchiaffinoKMShawarynMABlumDAssessing the psychosocial impact of multiple sclerosis: Learning from research on rheumatoid arthritisJ Neuro Rehab1996108189

- RudickRAMillerDCloughJDGraggLAFarmerRGQuality of life in multiple sclerosisArch Neurol199249123712421449401

- AronsonKJQuality of life among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregiversNeurology19974874809008497

- WhiteDMTreating the family with multiple sclerosisPhys Med Rehabil Clin N Am199896756879894117

- GregoryRJDislerPFirthSCaregivers of people with multiple sclerosis: A survey in New ZealandRehabil Nurs19962131378577979

- DrummondMFO’BrienBStoddartGLMethods for the Economic Evaluation of Healthcare ProgrammesOxfordOxford University Press1997

- StevensonVLThompsonAJThe management of multiple sclerosis: current and future therapiesDrugs today19983426728215094856

- FreemanJJohnsonJRollinsonSThompsonAHatchJStandards of health care for people with MS Multiple Sclerosis Society; September 1997.

- NaloneMLomaestroBOutcomes assessment of drug treatment in multiple sclerosis trialsPharmacoeconomics1996919821010160097

- MiloRPanitchHGlatiramer acetate or interferon-b for multiple sclerosis? A guide to drug choiceCNS Drugs199911289306

- The IFBN Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and the University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: Final outcome of the randomized controlled trialNeurology199545127712857617182

- JacobsLDCookfairDLRudickRAHerndonRMRichertJRIntramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis: the Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG)Ann Neurol1996392852948602746

- PRISMS Study GroupRandomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosisLancet1998352149815049820297

- European Study Group on Interferon beta-1b in Secondary Progressive Multiple SclerosisPlacebo-controlled multicentre randomised trial of interferon beta-1b in treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosisLancet1998352149114979820296

- The IFBN Multiple Sclerosis Study GroupInterferon beta-1b is effective in relapse-remitting multiple sclerosis, I: Clinical results of a multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trialNeurology1993436556618469318

- The IFBN Multiple Sclerosis Study Group, University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis GroupNeutralizing antibodies during treatment of multiple sclerosis with interferon beta-1b: Experience during the first three yearsNeurology1996478898948857714

- PanitchHGoodinDFrancisGBenefits of high-dose, high frequency interferon beta-1a in relapse remitting multiple sclerosis are sustained to 16 months: final comparative results of the EVIDENCE trialJ Neurol Sci2005239677416169561

- SchwidSRThorpeJShariefMEnhanced benefit of increasing beta-1a dose and frequency in relapse remitting multiple sclerosis: the EVIDENCE studyArch Neurol20056278579215883267

- Sandberg-WollheimMBeverCCarterJComparative tolerance of IFN beta-1a regimens in patients with relapse remitting multiple sclerosisJ Neurol200525281315654549

- JacobsLDBeckRWSimonJHKinkelRPBrownscheidleCMMurrayTJIntramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy initiated during a first demyelinating event in multiple sclerosisN Engl J Med200034389890411006365

- Placebo-controlled multicentre randomised trial of interferon beta-1b in treatment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. European Study Group on interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive MSLancet1998352149114979820296

- KapposLPolmanCHFreedmanMSfor the BENEFIT Study GroupTreatment with interferon beta1-b delays conversion to clinically definite and McDonald MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromesNeurology2006671242124916914693

- PRISMS Study Group and the University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis GroupPRISMS-4: long-term efficacy of interferon beta1-a in relapsing MSNeurology20015616281636 [erratum Neurology. 2001;57:1146].11425926

- GoodinDSFrohmanEMGarmanyGPDisease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosisNeurology200258168178

- ForbesRBLeesAWaughNSwinglerRJPopulation based cost utility study of interferon beta-1b in secondary progressive multiple sclerosisBMJ19993191529153310591710

- van OostenBWTruyenLBarkhofFPolmanCHChoosing drug therapy for multiple sclerosis: an updateDrugs1998565555699806103

- MäurerMRieckmannPRelapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: what is the potential for combination therapy?BioDrugs20001314915818034521

- RiceGPATretment of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: current recommendations and future prospectsBioDrugs19991226727718031181

- Weinstock-GuttmanJacobsLDWhat is new in the treatment of multiple sclerosis?Drugs20005940141010776827

- FillippiniGMunariLIncorvaiaBInterferons in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic reviewLancet200336154555212598138

- AmatoMPPharmacoeconomic considerations of multiple sclerosis therapy with the new disease-modifying agentsExpert Opin Pharmacother200452115212615461547

- lacheneckerPRieckmannPHealth outcomes in multiple sclerosisCurr Opin Neurol20041725726115167058

- TrygveHolmoyCeliusGulowsenElisabethCost effectiveness of natalizumab in multiple sclerosisExp Rev Pharmacoeconom Outcomes Res200811121

- KobeltGHealth economic issues in MSInt MS J200613172616420781

- CleggABryantJImmunomodulatory drugs for multiple sclerosis: a systematic review of clinical and cost effectivenessExpert Opin Pharmacother2001262363911336612

- BryantJCleggAMilneRSystematic review of immunumodulatory drugs for the treatment of people with multiple sclerosis: is there good quality evidence on effectiveness and cost?J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20017057457911309449

- TeitelbaumDMeshorerAHirshfiledTSuppression of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by a synthetic polypeptideEur J Immunol197112422485157960

- SimpsonDNobleSPerryCGlatiramer acetate: a review of its use in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosisCNS Drugs20021682585012421116

- JohnsonKPBrooksBRFordCCSustained clinical benefits of glatiramer acetate in relapsing multiple sclerosis patients observed for 6 years: Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study groupMult Scler2000625526610962546

- MikolDDBarkhofFChangPREGARD study groupComparison of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a with glatiramer acetate in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (the Rebif vs Glatiramer Acetate in Relapsing MS Disease [REGARD] study): a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trialLancet Neurol2008790391418789766

- http://www.mssociety.org.uk/research/index.html.

- HartungHPGonsetteRKonigNMitoxantrone in progressive multiple sclerosis: A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised, multicentre trialLancet20023602018202512504397

- GaniRGiovannoniGBatesDCost-effectiveness analyses of natalizumab (Tysabri) compared with other disease-modifying therapies for people with highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in the UKPharmacoeconomics20082661762718563952

- PolmanCHO’ConnorPWHavrdovaEA randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosisN Engl J Med200635489991016510744

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPModeling the cost-effectiveness of a new treatment for MS (natalizumab) compared with current standard practice in SwedenMult Scler20081467969018566030

- http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/word/TA127Niceguidanceword.doc. Accessed May 2009.

- GuoSBozkayaDWardATreating relapsing multiple sclerosis with subcutaneous versus intramuscular interferon-beta-1a: modelling the clinical and economic implicationsPharmacoeconomics200927395319178123

- BrownMGMurrayTJSketrisISCost-effectiveness of interferon beta-1b in slowing multiple sclerosis disability progression. First estimatesInt J Technol Assess Health Care20001675176711028131

- ChilcottJMcCabeCTappendenPModelling the cost effectiveness of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate in the management of multiple sclerosisBMJ200332652212623909

- KobeltGJönssonLFredriksonSCost-utility of interferon β1b 1-b in the treatment of patients with active relapsing-remiting or secondary progressive multiple sclerosisEur J Health Econom200345059

- ParkinDMcNameePJacobyAMillerPThomasSBatesDA cost-utility analysis of interferon beta for multiple sclerosisHealth Technol Assess.199824iii549580870

- ParkinDJacobyAMcNameePMillerPThomasSBatesDATreatment of multiple sclerosis with interferon b: an appraisal of cost-effectiveness and quality of lifeJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20006814414910644777

- PhillipsCJGilmourLGaleRPalmerMA cost utility model of beta-interferon in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosisJ Med Econ200143550

- ProsserLAKuntzKMCost-effectiveness of interferon beta-1a, interferon beta-1b, and glatiramer acetate in newly diagnosed non-primary progressive multiple sclerosisValue Health2004755456815367251

- DetournayBThe value of economic modelling studies in the evaluation of treatment strategies for multiple sclerosisValue in Health200251211873378

- PhillipsCJThe cost of multiple sclerosis and the cost effectiveness of disease-modifying agents in its treatmentCNS Drugs20041856157415222773

- KendrickMJohnsonKILong term treatment of multiple sclerosis with interferon beta may be cost-effectivePharmacoeconomics200118455311010603

- McNameePParkinDCost-effectiveness of interferon beta for multiple sclerosis: the implications of new information on clinical effectivenessHealth Technol Assess199924169179

- IskedjianMWalkerJHEconomic evaluation of Avonex (interferon beta-Ia) in patients following a single demyelinating eventMult Scler20051154255116193892

- GrimaDTTorrenceGWFrancisGRiceGPRosnerAJLafortuneLCost and health related quality of life consequences of multiple sclerosisMult Scler200069798

- KobeltGJönssonLHenrikssonFCost-utility of interferon beta 1b in secondary progressive multiple sclerosisInt J Technol Assess Health Care20001676878011028132

- KobeltGJönssonLMiltenbergerCCost-utility of interferon beta 1b in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, using natural history disease dataInt J Technol Assess Health Care20021812713811987436

- LazzaroCBianchiCPeracinoLEconomic evaluation of treating clinically isolated syndrome and subsequent multiple sclerosis with interferon beta-1bNeurol Sci200930213119169625

- LepenCCoylePVollmerTLong-term cost effectiveness of interferon-beta-1a in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an econometric modelClin Drug Investig200323571581

- BoseULadkaniDBurrellAShariefMCost-effectiveness analysis of glatiramer acetate in the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosisJ Med Econ20014207219

- JohnsonKPBrooksBRCohenJAExtended use of glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) is well tolerated and maintains its clinical effect on multiple sclerosis relapse rate and degree of disabilityNeurology1998507017089521260

- KobeltGBergJLindgrenPCosts and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in EuropeJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20067791892616690691

- BergJLindgrenPFredriksonSKobeltGCosts and quality of life of multiple sclerosis in SwedenEur J Health Econ20067S75S8517310342

- BellCGrahamJEarnshawSCost-effectiveness of four immunomodulatory therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a Markov model based on long-term clinical dataJ Manag Care Pharm20071324526117407391

- TouchetteDRDurginTLA cost-utility analysis of mitoxantrone hydrochloride and interferon beta-1b in the treatment of patients with secondary progressive or progressive relapsing multiple sclerosisClin Ther20032561163412749517

- Stolp-SmithKAAtkinsonEJCampionMEHealth care utilization in multiple sclerosis: A population-based study in Olmstead County, MNNeurology199850159416009633699

- StevensAColin-JonesDGabbayJQuick and Clean: authoritative health technology assessment for local health care contractingHealth Trends199527374210153156

- DonaldsonCMugfordMValeLUsing systematic reviews in economic evaluation: the basic principlesDonaldsonCMugfordMValeLEvidence-Based Health Economics: From Effectiveness to Efficiency in Systematic ReviewLondonBMJ Books2002

- TowseAPritchardCDoes NICE have a threshold? An external viewTowseAPritchardCDevlinNCost-effectiveness Thresholds: Economic and Ethical IssuesLondonOffice of Health Economics2003

- Department of HealthCost-effective provision of disease modifying therapies for people with multiple sclerosis Health Service Circular 2002/004, February 2002. http://www.info.doh.gov.uk/doh/coin4.nsf/12d101b4f7b73d020025693c005488a9/f4b139af5a7d8c2400256b52002e46e8/$FILE/004hsc2002.PDF

- FearonWFYeungACLeeDPCost-effectiveness of measuring fractional flow reserve to guide coronary interventionsAm Heart J200314588288712766748

- O’BrienBJGertsenKWillanARFaulknerLAIs there a kink in consumers’ threshold value for cost-effectiveness in health care?Health Econ20021117518011921315