Abstract

Intimate partner homicide suicide (IPHS) constitutes the most violent domestic abuse outcome, devastating individuals, families, neighborhoods and communities. This research used content analysis to analyze 225 murder suicide events (444 deaths) among dyads with at least one member 60 or older. Data were collected from newspaper articles, television news transcripts, police reports and obituaries published between 1999 and 2005. Findings suggest the most dangerous setting was the home and the majority of perpetrators were men. Firearms were most often employed in the violence. Relationship strife was present in some cases, but only slightly higher than the divorce rate for that age group. Illness was cited in just over half of the cases, but 30% of sick elderly couples had only a perpetrator who was ill. Evidence of suicide pacts and mercy killings were very rare and practitioners are encouraged to properly investigate these events. Suicidal men in this age range must be recognized as a potential threat to others, primarily their partner. Homicide was sometimes the primary motive, and the perpetrators in those cases resembled the “intimate terrorist.” Victims in those cases were often terrorized before the murder. Clinicians are educated about the patterns of fatal violence in later life dyads and provided with strategies for prevention.

Introduction and background

Elder abuse is a recognized social problem, which is thought to be increasing in magnitude with the aging of the population (CitationBonnie and Wallace 2002). Severe harm can be perpetrated by trusted family members, including the intimate partner. In the worst cases, fatalities may result for both members of the elderly dyad in what is commonly known as a “murder-suicide.” It is vital that these actions be recognized as domestic violence. The author’s academic specialties are in the areas of elder abuse, dyad aggression and family violence (CitationSalari and Baldwin 2002; CitationSalari 2006), but this work benefits further from her previous experience as a hotline volunteer and victim’s advocate for a battered women’s coalition. This manuscript is dedicated to the prevention of intimate partner homicide suicide among older couples. Clinicians are advised of prevention strategies that can be gleaned from preliminary findings of a sample of 225 events in the US between 1999 and 2005.

Later life intimate partner homicide suicide (IPHS) represents the most severe form of domestic partner abuse and usually results in at least two deaths. IPHS is lethal for individuals and has far reaching effects on public health as events traumatize families, friends, neighborhoods and entire communities. Men are most often the perpetrators and women the victims (CitationViolence Policy Center 2002). In some instances secondary victims outside the intimate partnership are also injured or killed (eg, children, grandchildren, friends, siblings or neighbors). The criminal justice system is bypassed since both victim and perpetrator are deceased, a condition which serves as a barrier to closure among family survivors and significant others. A “suicide contagion” effect has been noted, including situations of murder-suicide clusters and “copy cat” responses by persons living nearby who are at risk of imitating this negative behavior (CitationCDC 1994; CitationThe Virginian Pilot 2000).

Scholars who focus their research on domestic violence have acknowledged the topic is difficult to study. Self reports on surveys may be subject to error from “social desirability effects,” which might cause both perpetrators and victims to misreport or omit their experiences (CitationSalari and Baldwin 2002). Shelter programs have clients who are attempting to flee domestic violence, but their populations are not representative and usually systematically lack victims from the older generations. Homicide suicide studies have the potential to examine severe abuse, without the typical difficulties found in domestic violence research. Although the motive may not always be clear, it is possible to study the perpetrator, victim, setting, relationship and consequences of the event.

IPHS is so severe that news media outlets tend to include the events in their reporting. This publicity can be utilized by researchers who wish to study severe domestic violence. Newspaper surveillance studies have been useful to examine the relationships between perpetrators and victims and determine the approximate incidence of homicide suicides in the United States (CitationMalphurs and Cohen 2002; CitationVPC 2002). Fatality reports in a few individual states have also been helpful indicators of fatal family violence (CitationWashington state coalition against domestic violence 2003), but there is currently no national counting system to officially link homicide and suicide deaths together in the US. Treating these as separate events serves as a barrier to homicide-suicide prevention (CitationMarzuk Tardiff and Hirsch 1992; CitationAderibigbe 1997).

Estimates suggest up to 1,500 deaths per year result from homicide suicide, and the majority take place among intimate partners (CitationMarzuk Tardiff and Hirsch 1992; CitationMalphers and Cohen 2002; CitationViolence Policy Center 2002). States with larger populations (FL, CA, TX, NY) have the greatest representation, and Florida’s high proportion of elderly in the population gives it a first place ranking (CitationMalphurs and Cohen 2002; CitationViolence Policy Center 2002). Elder murder-suicides have increased recently, a trend that will likely continue (CitationCohen et al 1998) due to the aging of the Baby Boom (Prichard 1992; CitationCBS News 2004), the greater potential for poor health in old age and the heightened suicide rate among older white males (CitationVPC 2002). Another factor may be the greater firearm availability among seniors (CitationConwell et al 2002; CitationChristian Science Monitor 2004), including those with dementia (CitationReuters Health 1999). Recent increases in intimate partner homicide victimization for women aged 35–49 and 65 and over are also a concern (US CitationDepartment of Justice 2001).

Additional factors that may increase the vulnerability of older persons are related to gender socialization and the use of formal services. Current cohorts of elderly persons were socialized during an era where (1) mental health treatment was stigmatized, (2) victims were discouraged from notifying police during a domestic dispute, and (3) abused partners did not obtain legal protection, such as a restraining order. Gender socialization norms in the past differed from modern standards and elderly cohorts were influenced to accept the husband’s role in the family as dominant, including behaviors that would be seen as controlling or emotionally distant by today’s standards (CitationSalari and Zhang 2006).

What is the role of dementia in later life homicide suicide? While some have introduced a case study approach where the perpetrator had Alzheimer’s disease (CitationLecso 1989), other studies have suggested that perpetrators with AD are more likely to commit suicide only, rather than a combined homicide-suicide (CitationMaphurs et al 2001). Perhaps this pattern is due to the relatively greater complexity of the homicide-suicide act. More commonly, victims may suffer from dementia and have a caregiver who suffers ill effects of stress and burden, without a proper support system in place. There may also be a homicide suicide perpetrator who holds a dependent-protective attachment to the spouse and feels a strong need to control their fate (CitationMalphurs et al 2001).

Elder murder-suicide has traditionally been studied by researchers in forensics and psychiatry. CitationRichman (2001) suggests that impulses of a death wish, homicidal ideation, suicide pact and murder-suicide ideation are present far more frequently than is commonly realized. The literature argues that untreated depression represents a major causal factor and there is a great need for medical intervention by practitioners (CitationRosenbaum 1990; CitationCohen et al 1998). Clearly, depression plays a major role for those who have chosen suicide, and pharmaceutical or other mental health treatment could have potentially helped alleviate the problem. There are also reports of Axis II personality disorders among perpetrators of homicide-suicide (CitationRosenbaum 1990).

Why do suicidal perpetrators include their partners in these violent events? Those who have a primarily suicidal motive may perceive that their partner would suffer without them, and they make the unilateral decision to end life for both parties. The belief that the perpetrator is doing the victim a favor is sometimes termed “altruistic” motive (CitationMarzuk et al 1992). Obviously, the act is not actually beneficial to the victim, so an “egotistic” term for this motive might better describe the situation. Another potential suicidal motive involves mutual consent of both parties, which is considered a “suicide pact” or in the case of severe illness, a “mercy killing.” The CitationCDC (2004) definition of mercy killing involves an act to “bring about immediate death allegedly in a painless way and based on a clear indication that the dying person wished to die because of a terminal or hopeless condition (8–18).” Researchers coding violent deaths are warned not to assume that a murder-suicide by a sick, elderly couple qualifies, unless specific evidence exists. Media reports of IPHS in later life often describe the motive as a “mercy killing” without proper investigation into the specifics of the case, especially with regard to victim consent. Mercy killing motives are rare (CitationMalphurs and Cohen 2005; CitationSalari 2005).

It is important to distinguish that in other cases the primary intent is homicide and the event represents domestic violence rather than a primarily self destructive motive (CitationSalari and Lefevre-Sillito 2006). It is well known in the domestic violence literature that the most dangerous time in an abusive relationship is when the victim is leaving or has left. Homicide risk is greater for victims who are in an estranged, versus intact relationship (CitationJohnson and Hotton 2003). For that reason, we include couples who are ex-intimates or in the process of separation in this research.

Research on domestic violence (DV) distinctions have advanced in recent years, but little is known about how they apply to later life homicide-suicide. According to CitationJohnson and Ferraro (2000), the most dangerous domestic violence perpetrator is an intimate terrorist (IT) who uses threats, violence, and other power and control tactics to severely isolate the victim. IT perpetrators are typically male, patriarchal, blame others, take no responsibility for their actions and are potentially homicidal (CitationJohnson and Ferraro 2000). One could speculate that in the IPHS, the suicide act is secondary to the primary homicide motive and may represent an attempt by the IT to prevent prosecution for their crime. There may be a resistance among family members and others to recognize the intimate terrorist among older persons. Clinicians need to be aware of the different primary motivations for IPHS violence, in order to detect this form of abuse and shelter the victim before fatalities result.

There may be other issues, such as a psychotic break or substance abuse that would explain the choice of intimate partner homicide-suicide. Substance abuse has been found to be a strong predictor of injurious aggression in a national sample of dyads (CitationSalari and Baldwin 2002). Studies of domestic homicide indicate a large role of alcohol, but homicide-suicide cases tend to have some other mechanism at play – as autopsies rarely find intoxication to be a factor (CitationRosenbaum 1990).

This research uses content analysis to examine a large sample of news reports of 225 elderly intimate partner homicide suicide events in the US between 1999 and 2005. Descriptions of the characteristics of victims and perpetrators (eg, gender, health status), the location, motivations, the role of domestic violence, mental illness, suicidal ideation and substance abuse are provided and discussed Strategies to prevent IPHS are introduced to clinicians based on the research findings, as well as advisories from suicide prevention and domestic violence victim’s advocacy organizations.

Data and methods

Many previous homicide-suicide studies have utilized small samples from a limited geographic area (CitationRosenbaum 1990; CitationCohen et al 1998; CitationMalphurs et al 2001; CitationCampanelli and Gilson 2002; CitationMalphurs and Cohen 2005). Others have focused on determining national prevalence and have included relationships between perpetrator and victim that were not necessarily intimate partners (eg, coworkers, neighbors, siblings, etc.) (CitationAderibigbe 1997; CitationCapanelli and Gilson 2002; CitationMalphurs and Cohen 2002; CitationViolence Policy Center 2002). This study specifically limits the examination to intimate partner homicide suicide events, rather than grouping these other relationships into one sample. Examining both members of the dyad has been a recent and important development in domestic violence research (CitationSalari and Baldwin 2002), but in-depth examinations have yet to focus on older couples specifically. This sample goes beyond estimates of IPHS prevalence to provide clinicians with patterns of within group differences associated with homicide-suicide in later life.

Here, the definition of intimate partners could also include ex-partners, since the greatest danger in a domestic violence relationship is when the victim is leaving or has left the relationship (CitationJohnson and Hotton 2003). The timing of the homicide and suicide acts most often occur in an immediate time frame, but occasionally the murder may precede the suicide by a longer stretch of time. This research conforms to previous studies by counting the administration of potentially lethal acts of homicide and suicide within one week of one another (CitationCampanelli and Gilson 2002).

This study is part of a larger project that examines over 1,600 deaths from 731 intimate partner homicide suicide events among young adults (18–44), middle aged (45–59) and elderly dyads (60+). Here we analyzed just the news reports describing 225 IPHS events of elderly persons. Data were collected from TV news cast transcripts, newspaper articles, obituaries and published police reports from a variety of sources. Along with traditional search engines, the most helpful website was http://www.newslink.org which provided access to approximately 1,193 news sources online. Keyword searches included homicide suicide, murder suicide, couple found dead, elderly murder suicide, etc. The time span (1999–2005) was chosen for several reasons, including the ability to successfully search archives, to include a large sample size and to increase the probability of including all states. Earlier years (1998 and earlier) were determined to have less success with regard to news archive searches and availability. Intimate partner homicide suicide reports were analyzed using quantitative and qualitative content analysis.

Content analysis has been defined as a research technique that offers objective, systemic and quantitative description of the content of communications (CitationBerelson 1952). These methods require an in-depth examination of the reports, along with proper coding of variables and reliability checks. In this research, agreement was reached by three research investigators who discussed the case until a code could be determined. For the IPHS preliminary sample, codes were represented in categories on a grid, as researchers catalogued the date, day of the week, perpetrator age, victim age, perpetrator name/sex, victim name/sex/relationship, secondary victims, pet victims, military history, occupation, method of murder-suicide (caliber firearm, etc.), timing, location of bodies (eg, home, yard, car, bed, hallway), SES, state/city location, rural/urban, health conditions, domestic violence history, protective orders, police involvement, and a comment section for information such as neighbor comments, social isolation, separation, divorce and the conditions under which they were found. Cases were analyzed as a whole and a determination of “primary motive” was made based on a number of factors. The motive categories were developed in CitationSalari and Lefevre-Sillito (2006) and conservative methods were used to code cases (2 or more characteristics must be present for code). Based on evidence, perpetrators were primarily: (1) suicidal (ie, sad, known suicidal ideation, turmoil, confusion, note, financial trouble, severe health problems, quiet, pleasant personality, not an angry person); (2) homicidal (domestic violence history, threats, intimate terrorist, protective order, crimes against victim, stalked, kidnapped, severe wounds, jealousy, known to be angry/nasty); (3) influenced by drug/alchohol; and (4) severe mental health problems (ie, psychotic break, paranoia, etc.). Cases were coded as missing if they were unclear or the motive was absent in the news report.

Qualitative content analysis uses procedures to preserve the advantages of quantitative content analysis, as developed by communication science researchers and further develop the methods to include qualitative-interpretive steps of analysis (CitationMayring 2000). Qualitative data from narratives of police personnel, neighbors and family members were analyzed to determine what commonalities and differences were evident in the public reactions. These relevant groupings of verbal narratives have been represented in the research by using direct quotes and case studies to describe the concepts and theoretical trends. This triangulation strengthens both quantitative and qualitative data analysis by combining insights from both (CitationMax and Lynn 2006) and provides a rich picture of the circumstances surrounding IPHS among later life dyads.

Results

Elderly couples with at least one member over 60 who were involved in homicide suicide between 1999 and 2005 were analyzed in this research. In the 225 domestic violence events, 444 deaths resulted, including 16 who were secondary victims. Survival was very rare, but in 22 cases there was at least one survivor in the intimate dyad. Several of the reports of IPHS mentioned that this event did not exist alone, but there had recently been others in the local geographic vicinity. This finding is not conclusive, but indicates that homicide-suicide contagion may be a real phenomenon.

The partnerships were mostly intact marriages and the husbands tended to be older than the wives (sometimes decades older). illustrates that the vast majority of violence perpetrators (96%) were men.

Most victims did not consent to the act and when the danger was known to the victim, some fought back or attempted to flee. However, there was evidence that most were surprise attacked and seemed unaware of their fate. Reports noted victims were engaged in some other activity such as eating, sleeping or resting.

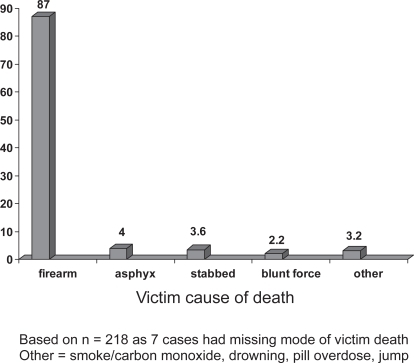

illustrates the vast majority of victims were killed/injured by a firearm (87%) and other methods made up a minority of cases. There were some situations where perpetrators changed the mode of death and died of other methods, such as hanging. In most cases and both partners died of firearm head wounds, and often the victim was shot in the back or back of the head – which demonstrates the theory of a surprise attack.

It was impossible to determine the socioeconomic status of the couple in every case, but in general there was evidence of a great variety. Most owned their homes, and the location of those homes ranged from trailer parks to wealthy gated communities. In a few cases, financial problems and mounting debt were cited as a pre-curser to the violence. Difficulties arose from severe gambling debt, unpaid medical bills, income tax concerns and perpetrators who had been victims of financial scams.

The perpetrator and victim were often retired, but their previous occupations were sometimes listed. Perpetrator occupations included veteran, police officer, medical doctor, a urban planner, factory worker, farmer, air traffic controller, guidance counselor, decorator, school bus driver, elected city employee, handyman, minister (pastor, deacon), teacher, professor, IBM worker, school principal, jazz musician, restaurant owner, fire fighter, mortgage broker and truck driver. Victims were more often women who were primarily homemakers. Many were active in voluntary organizations and for those who had jobs/careers, their occupations included, medical doctor, nurse, dentist, teacher, store manager, cook, grocery worker, restaurant owner, guidance counselor, waitress and maid. Clearly, there was a great variety in the life work of the people who were affected by this lethal domestic violence.

Health status

Elderly persons are more likely to have chronic health problems than other age groups. This research discovered that health issues were cited in a slight majority of cases (55%), but the conditions did not always relate to the motive for the IPHS. Approximately 7.5 percent of victims had some form of dementia, but it was rarely found among perpetrators. Of those dyads with reported health problems, 34 percent had only a victim who was ill, 30 percent had only a perpetrator who was ill and in 36% of ill couples both had health problems. It is worth noting that of the 225 cases, 101 elderly couples had no health problems listed at all. Despite widespread attention to poor health motives, IPHS in elderly couples is clearly not just about poor health status.

There were seven cases where someone from the couple had been recently hospitalized. In one case the husband was described as being frustrated with frequent trips to the hospital for his wife’s medical problems. He had once said that he “wished it would all be over.” In two other cases, it was the perpetrator who had been hospitalized for mental health reasons. Mental health will be addressed later in greater depth.

Location

Approximately ten events involved residents (or recently discharged residents) in a nursing home or assisted living (AL) facility. The proportion associated with these settings was 4.4 percent, which was not disproportionately higher than the 4.3 percent institutionalization rate of the elderly in the US population (CitationNational Center for Health Statistics 2004). It cannot be considered that a nursing home is a particularly high risk setting for this violence. However, evidence suggests that when they did occur, homicide suicide events severely disrupted the entire residence facility. An AL staff member described the fallout this way “We are used to dealing with death here, but not in such a tragic way. It’s a shock. We are working through the trauma of it.” In a few of these cases, the husband still lived at home and the wife was institutionalized, representing a physical separation in living arrangements. In three cases, the ill spouse was intentionally discharged and brought home, a move which most likely overwhelmed the male caregiver and contributed to the homicide suicide event. There is also a chance that the IPHS event had been pre-planned in these cases, and the perpetrator preferred to make the couple’s home the location of his final act. In other situations where the couple lived at home, and the husband was the caregiver, he seemed to be resistant to the option of nursing home admission. One victim had severe AD when her husband committed the fatal violence. A neighbor remarked “He couldn’t watch her deteriorate, and wasn’t going to leave her in a nursing home.” The assumption in that statement seemed to suggest that the nursing home option would have been somehow worse than the murder-suicide event.

The home was the most common setting for the IPHS, which suggests that the home is not always a safe place for elderly persons. In addition, the victim was most often found in the bedroom, which is perhaps an indicator of the intimacy of the relationship between victim and perpetrator. Non-intimate partner homicide perpetrators typically do not have access to the private setting of a bedroom to commit the crime. The location of the incident also gives a glimpse into the victim’s trust of the perpetrator and her activity prior to the murder, as many were sleeping or resting. There were other instances where victims appeared to be eating or sitting in another room of the house. Occasionally they had been in the yard, but the vast majority of events occurred indoors – in the privacy of the home.

Community dwelling elderly couples had sometimes used home-based services such as hospice (2) and visiting nurses or caretakers (3), and personnel from these agencies sometimes discovered the bodies. Evidence suggested that the vast majority of community dwelling couples employed no formal help prior to their deaths. So, it cannot be assumed that all formal services available to the couple were exhausted prior to the decision to commit this crime.

Retirement communities might provide better access to aging services because of the residential concentration of older people. In this sample, there were at least six couples who lived in retirement community environments. Their deaths had a negative impact on the entire neighborhood. One woman described her disappointed reaction to the couple who leapt from an upper story window of a retirement structure “It was cruel to themselves and the whole building.” Others in the building described their own difficulty conducting their everyday routines, with the memories of the violence that had taken place there. In these situations neighbors may show symptoms of post traumatic stress disorder; grief counseling would clearly be indicated.

Suicidal primary intent

Primary motive was determined in 173 cases and unclear or missing in 52. Approximately 128 (74%) of those with a detected primary motive had a perpetrator who was suicidal in nature. In a related study, it was determined suicidal primary intent was much more common among the elderly than young adult or even middle aged perpetrators (CitationSalari and Lefevre-Sillito 2006). The typical situation involved a perpetrator who planned to kill him/herself, but at some point prior to the act, made the decision to kill their partner. They may have been concerned about how the spouse would handle the suicide. Another possibility is that they viewed their spouse as an extension of themselves, rather than an autonomous person.

In some situations, depression was evident prior to the event. For example, one wealthy man described as “a model husband to his high school sweetheart” had been bothered by the recent controversial sale of his family business. His son said “Dad looked down and was quieter than normal at this 60th birthday party last month.”

In another case both of the partners had some health problems and the husband (67) had foreshadowed his plan in a statement to neighbors “I don’t know what is going to happen to your neighbors… All we do is live on pills, pills, pills, pills…” After the homicide-suicide event, a neighbor stated “They were quiet, good people… It’s really sad… It is pretty hard to live in a house with someone in depression. It put [wife] in a bad position. She tried to remain positive.” In this case, a physician visit had been previously scheduled for the week following the event, but the perpetrator did not wait for that potential intervention.

Typically, in a primarily suicidal case, neighbors did not know of previous problems between the partners. Depression was not necessarily obvious in all situations. Neighbors and acquaintances were often shocked to hear the fate of the elderly couple. One close friend stated “The murder suicide came as a total surprise. They had no financial problems, no ongoing arguments. I was with him every weekend and you talk about that sort of thing to your best friend.” Narratives tended to be complementary of the victim and the perpetrator. Neighbors in another case said “You couldn’t ask for better neighbors… They never fought… I’m close to being in shock over this… They were always upbeat, just he most pleasant people you would ever want to meet.”

The deaths of two volunteer “citizen cops” caught neighbors off guard as they recognized that the victim had future plans “There was not even a hint that there was a problem … they seemed so happy … devoted to each other … the victim was happy about an upcoming visit from her brother … I was shocked – I can understand wanting to kill yourself, but why take someone else’s life?”

Even in the rare “suicide pact” cases (4%), special care was taken to determine the consent of each party. In some cases with joint or victim authored suicide notes, the intent was clearly mutual. These would conform more closely to the CDC “mercy killing” definition. In other cases, it appeared that one partner went along with the violence, but was actually coerced into that decision by the partner with a more dominant personality. Two surviving perpetrators claimed to have the victim’s consent in a suicide pact arrangement, but both were eventually charged with murder. In one case there was evidence of previous domestic violence by the perpetrator (52) against the victim (73) (a gay male couple). In the other situation, the husband (80) had claimed his wife (74) had terminal cancer, but the autopsy found she had no evidence of any illness.

Domestic violence and homicidal primary intent

Homicide appeared to be the primary intent of 24 percent (41) of the motive determined cases. In these situations, victims sometimes attempted to flee, fought back or hid from the attack. Clearly these victims were often terrorized prior to their death.

A history of domestic violence in the dyad had been known to others prior to the IPHS in 32 cases (14%) of the total events sample. For one victim (65) who worked as a nurse practitioner, co-workers said she had spoken of stress at home. Her physician boss noted “I suppose we knew there was a bit of difficulty, but we never anticipated something like this.”

Protective orders (PO) are legal documents designed to keep the perpetrator away from the victim. Unfortunately, they are not always successful measures of safety, as perpetrators may violate the order. In this sample, four POs had been issued prior to the intimate partner homicide suicide event. This suggests two points 1) the legal order was not effective in protecting these victims, and 2) there was a low rate of reliance on formal legal help among older victims of domestic violence. Gender role socialization differs by birth cohort (CitationSalari and Zhang 2006) and older persons were taught to keep family problems a secret and protect family perpetrators. Another possibility is that these victims cohabitated with their perpetrators, so they were not necessarily eligible for a protective order.

Approximately twenty-eight (12.4%) of the cases contained evidence the perpetrator may have been an intimate terrorist (IT). Negative attitudes and behaviors of the perpetrator had been noticed in the past. In a rural Texas case, a neighbor described the victim (73) was a “nice, quiet person, soft spoken … really friendly.” A relative indicated the truth about the perpetrator (61) “George had a hot temper that may have gotten out of hand and caused this tragedy.”

Another common theme from the qualitative narratives suggested victims were severely isolated from others. Neighbor’s statements indicated “No one knew them in the 25 years of living here… They didn’t socialize with many of the neighbors.” In another case, the neighbor believed the wife (81) was not permitted by her husband (85) to speak to anyone “I tried to talk to her, she would smile and then turn her face. She didn’t dare.” Neighbors in that case noted that they were “private people” and the wife rarely left the house. In the situations described above, it is possible that the victim was being confined in the residence. The perpetrator demonstrated his “control” as he called 911 to report the homicide prior to his own death. Unfortunately, police responding to the scene saw no evidence of a struggle and concluded that it might have been consensual. It is important for law enforcement and medical responders to understand the dynamics of later life domestic violence in order to reach proper conclusions in these cases.

Communications

The researcher did not have access to actual suicide notes, but many reports (30) noted some written information was left at the scene. With the exception of 6 joint or victim authored notes, all were sole authored by the perpetrator. Often these documents represented a window into the perpetrator’s thinking prior to the suicide. In many cases, perpetrators left notes along with funeral plans and financial documents. Of the reports available, there seem to be 2 options: 1) narcissism and 2) blame the victim. In the reports that suggested a narcissistic tone to the notes, the killer focused mostly on his/her own lose ends or possessions, with little or no discussion of the event or the homicide victim. In IT cases, the perpetrator would sometimes leave a note that actually blamed the victim for causing the tragedy. In one such case, the victim (61) was stabbed six times with a knife in the neck and chest and her live-in boyfriend (66) killer left 2 notes describing his mounting frustration and blamed her for making him unhappy and in effect, causing both of their deaths.

There were also 13 cases where perpetrators reportedly called 911 after the murder. In some of those cases, the dispatch operator heard the firearm discharge during the perpetrator’s suicide. An Asian American father (65) left a recorded message on his son’s answering machine after he had bludgeoned his wife (65): “Your Mother is dead and your Father will be dead by the time anyone gets here.” It is not clear why perpetrators feel the need to call relatives or emergency services, but it represents a delay in their own demise – and perhaps a chance to prevent the self abuse. They may also be expressing a concern about what will happen with their own remains.

Relationship status

The vast majority of cases in later life had a married couple, who were living together at the time of the fatal domestic violence event. Approximately 13 percent of the cases had some sort of estrangement (separated, divorcing, divorced, or severe marital problems) associated with the relationship. Compared to the general divorce rate for those 60+ in the US, this was a disproportionately high incidence of relationship problems. Some victims had filed for divorce or made other plans to leave the relationship and others had already left. Perpetrator actions were sometimes reactions to these spurned relationships. In one case, after the break-up of a two-year relationship, the former boyfriend (63) stalked the victim (47), threatened her, followed her car to work, stopped her car in a grass median and killed her. He drove his car further down the road and suicided 6 miles away. The delayed suicide suggests the homicide was his primary motive in that case.

In another case where the couple was recently estranged after a 38 year marriage, the husband (60) had calmly played golf in the morning and later that day chased his screaming wife (57) down street and shot her in the back of the head. When police arrived, he shot himself. These events took place in front of the neighbors, who were severely endangered and traumatized by the incident.

The estrangement usually represented a new change to the relationship, however there were some cases where the perpetrator seemed to hold a grudge or became more upset when the victim had moved on to another relationship. In a Pennsylvania case, the former husband (78) (divorced 30 years ago) stalked and found his ex-wife (75) and her current husband (71) and killed them in their own basement, before he killed himself at the scene.

Substance abuse or psychotic break motive

Unlike other domestic violence situations, the IPHS events tended not to have alcohol or other substance abuse influences. There were a few cases (4) where perpetrators had suffered a severe change in their mental status, which may have contributed to the domestic violence. According to one account, the perpetrator’s (62) personality had “changed suddenly” and he became suspicious, paranoid and threatened to kill himself. After going for 3 days without sleep, he killed his wife (49) and himself.

Secondary victims

IPHS is sometimes fatal for secondary victims, such as teenaged or adult children, in-laws, extended family of the victim, grandchildren and even neighbors or friends. This sample had 16 persons who were injured or killed along with the intimate partner. In cases where the perpetrator was primarily suicidal, the secondary victims were often killed when they were sleeping or otherwise unaware of their fate. In contrast, those cases perpetrated by an intimate terrorist tended to involve a protracted period of terror for the secondary victim(s). The son (9) of an arguing California couple witnessed his mother’s (44) murder and was shot by his father (83). He pretended he was dead and ran for help after he heard his father’s suicide.

Discussion

According to the World Health Organization, about 1 million persons worldwide commit suicide per year, which represents a greater death toll than the casualties of war (CitationKyodo World News Service 2004). Around the world, elderly people have a higher risk of completed suicide than any other age group, but their plight receives little attention and few efforts toward prevention (CitationO’Connell et al 2004). Homicides are the only crime that regularly results in the suicide of the perpetrator, an indication that one can be suicidal and homicidal at the same time (CitationGillespie et al 1998). It is important for practitioners to recognize that elder abuse can be perpetrated within an intimate dyad and traumatic fatalities may result.

Previous studies have not provided a clear examination of IPHS in relation to domestic violence. This research represents the collection and analysis of the largest sample of late life intimate partner homicide suicide reports to date. Evidence suggested there are several causes of this domestic violence, and commission of this crime may lead others who are at risk to imitate the maladaptive behavior. For the perpetrator, the act represents self abuse along with the destruction of significant others. For the victim, there is a tragic loss of autonomy, a lack of control over end of life decision making, a tarnished legacy, and the ultimate criminal victimization by a partner who was trusted.

Substance abuse is widely regarded as a significant cause of domestic violence, suicide and homicide risk. However, this research did not detect alcohol or drug use as a major factor in the IPHS cases. Later life IPHS appears to occur when perpetrators tend not to be under the influence of substances, dementia, or major psychotic symptomology. There was evidence that depression played a role in the event for most perpetrators.

Suicidal older persons may represent significant danger to others. For the majority of perpetrators in this sample, suicide represented the primary intent of the violence. Major life crises and events were present in some cases and may have propelled the desperate fatal act. For example, financial loss, problems with the law, income tax worries, and the effects of natural disasters were cited among the stresses confronting the couple. Health problems were mentioned in slightly more than half of the couples, but CDC defined mercy killings were not common. Among the cases with reported poor health, there were many situations where only the perpetrator was ill, reflecting a suicidal plan based on one’s own suffering. In cases where the victim was sick or demented, the male caregiver may have been overwhelmed by the care required – but there was very little evidence that an attempt was made to reach out to available formal services such as nursing homes, assisted living, hospice, adult day centers, visiting nurses or homemaker services. Rather than a consensual suicide pact or a hopeless situation of mercy killing, the evidence suggested a dominant and controlling perpetrator made the unilateral decision without the consent (or knowledge) of the victim. CitationMulphurs and Cohen (2005) in an intensive examination of a small sample of murder-suicides in Florida, also found that most were not mercy killings. Even those that were consensual, tended to have a coercive perpetrator and dependent victim. These conclusions were supported in this analysis of IPHS news reports.

Warning signs existed for some, but were absent for others. In the cases that were motivated primarily by suicide, there were some situations where the perpetrator had made comments to others of a potential plan. In other cases, people close to the couple were shocked and surprised to find out the event had transpired as they perceived there were no clues predicting this maladaptive outcome.

There were also cases where the homicide appeared to be the primary motive of the perpetrator and the suicide was intended to prevent prosecution. In the majority of those cases, there was evidence to suggest the killer was what Johnson and Ferraro termed an intimate terrorist. Victims in those cases were often stalked, abducted and terrorized prior to death. Evidence left at the scene sometimes conveyed that the perpetrator did not take responsibility for the act and blamed the victim for the tragedy. This finding points to the importance of making distinctions in the study of domestic violence among elderly intimate partners.

This form of elder abuse is destructive and traumatic to individuals, families and communities. There should be attempts made to deter this maladaptive behavior in later life. Domestic violence events should never be viewed as romantic or altruistic as it is often erroneously reported in the news media (CitationSalari 2005). Strategies for prevention are presented below.

Strategies for detection and prevention

The following recommendations for clinicians are based on the findings of this research, the author’s experience as a victim’s advocate, as well as supplemental tips from suicide prevention networks (CitationAmerican Association of Suicidology 2006) and domestic violence victim’s organizations (CitationWebsdale 2000). It should be noted that these tools may not be exhaustive and may or may not be effective in all cases.

Suicidal ideation is normally perceived as a problem of self abuse. However, it should be recognized by clinicians that suicidal persons may be harmful to others as well. Clinician contact may be with either partner: the potential perpetrator or the victim. For that reason, a suicide assessment would be useful for the patient, but also for the patient’s spouse. This may be obtained through a face-to-face meeting with that partner, or if that option is not available, the patient’s perception of that person’s risk factors may suffice. Dyad vulnerability to IPHS may be assessed by inquiries into the following characteristics for either partner:

Existence of major life stresses

Difficulty seeing a way out of a bad situation

Recent experiences of grief and bereavement

Depressive symptomology – sleep disturbances

Personality traits: flexibility vs. need for tight control

Knowledge of and willingness to use aging services

Severe disappointment with aging services or nursing home care

Previous suicide attempt or threat of suicide

Previous domestic violence incident

Abusive behavior that escalates over time

Anger, rage, seeking revenge and violent reactions

One partner strives for power and control over other

Obsessive – possessiveness relationship characteristics

Stalking behaviors or ideation

Threats to kill either partner

Police or legal involvement (restraining orders)

Weapon possession (gun collections, hunting rifles, etc.)

Previous history of using a weapon in a dispute

One partner allows the other to make decisions and speak for them

Isolation from others including neighbors, friends, relatives

Confinement or entrapment in the house

Fights or estrangement from relatives or victim’s support network

Narcissistic perspectives

Patriarchal or misogynist views

Lack of empathy for others

Inability to recognize partner’s autonomy

Belief that ending life would do victim a favor

Recognize and attempt to treat underlying clinical depression

Recognize warning signs of suicide

Recognize other local IPHS events may make couples vulnerable to murder-suicide contagion

Be available to lend support to one or both members of the dyad

Ask direct questions about suicidal intentions

Don’t act shocked or judgmental about plans for suicide—but act to remove means

Assess access to firearms and take action to limit availability

Ask about stockpiles of pills, poisons – if affirmative, call poison control

Employ the assistance of the larger family network

Utilize the help of a mental health professional

Utilize religious/spiritual leaders

Recognize IPHS may or may not be related to poor health conditions

In the case of poor health, encourage (take initiative) the use of formal services, including those which can be delivered to the home

Do not strip decision making power away from potential victims

Empower victims to make their own decisions

Recognize that leaving an abusive relationship is a process – not to be done hastily

Call police or Adult Protective Services for investigation of abuse to self or family

Investigate the potential use of shelter services (sometimes not appropriate for elderly)

Treat older adults as adults – do not trivialize, baby talk, infantilize

Make the suicidal ideation known to larger support network, do not swear to secrecy

Call local or national hotlines for suicide prevention and domestic violence victims advocacy assistance on behalf of couple

For the terminally ill, hospice services can be encouraged to support the patient and family members

The victim of ongoing domestic violence (or a controlling spouse) has been stripped of decision making power. Victim’s advocates strive to empower victims, without dominating them and making their decisions for them. When well intentioned health professionals “take over” and push victims into services or shelters they are not ready to accept, the victim is more likely to backtrack on progress made and/or return to the dangerous relationship. Recognizing and acknowledging the plight someone who has been controlled is helpful, as she/he will become aware that other people see what is happening and they care. Another barrier to safe escape involves the effects of repeated trauma and psychological abuse. The victim may suffer from post traumatic stress disorder or a situation of “learned helplessness” where their passive responses make them unable to escape. Professionals must recognize that some abused persons may choose to never leave the home. Adults in many areas have the right to self determination and can refuse adult protective services (unlike abused children). Advocates are beginning to recognize that often the victims are the best judge of the specific circumstances. Leaving or taking out a protective order may put the abused person in greater danger. It is not helpful to minimize the process and insist “Why don’t you just leave?” Gentle support, listening, acknowledging the mistreatment and connecting the victim to local professionals can help facilitate the process of leaving or staying safer within the home. These rules of advocacy may be particularly difficult with an older victim who has been socialized to have little if any help from formal services and police agencies. With the help of aging services (eg, visiting nurses, hospice, etc.) and adult protective services, the home could be made a safer place, if the victim refuses to seek shelter elsewhere.

Intimate terrorist perpetrators may be very difficult to treat. Most do not accept any responsibility for their actions. This attitude was evident in some of the suicide notes where the perpetrator blamed the victim for causing the IPHS event. Battering prevention programs typically are not known for their success, especially when the perpetrator has been sent by the courts.

The results of the IPHS study also suggest there may be cases of severe partner violence without a long running history of domestic abuse. In these cases, the danger comes more from a suicidal spouse who makes the decision to unilaterally take everyone out together. These cases may be more difficult to detect and greater attention would be needed to be paid to treating the abuser and preventing his/her depression and suicidal ideation. Recognizing the potential harm to others by a suicidal person is also key to preventing multiple fatalities.

References

- AderibigbeYA1997Violence in America: a survey of suicide linked to homicidesJournal of Forensic Science426625

- American Association of Suicidology2006Understanding and helping the suicidal individual [online]Accessed 10/4/2006. URL: www.suicidology.org

- BerelsonB1952Content analysis in communication researchNew YorkFree Press

- BonnieRJWallaceRB2002Elder mistreatment: abuse, neglect, and exploitation in aging AmericaExecutive Summary. p 1.

- CampanelliCGilsonT2002Murder-suicide in New Hampshire, 1995–2000American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology232485112198350

- CBS News2004Senior suicide rate alarms doctorsCBSNEWS.com July 24, 2004.

- [CDC] Centers for disease control and prevention1994Suicide contagion and the reporting of suicide: recommendations from a national workshopMMWR Recommendations and Reports43(RR–6)918

- [CDC] Centers for disease control and prevention2004Coding manual: national violent death reporting system. NVDRS Version 2 Page 818National center for injury prevention and control. US Department of health and human services. Available online www.cdc.gov/injury

- Christian Science Monitor2004Elderly and armedTucson, AZ Jan. 7.

- CohenDLlorenteMEisdorferC1998Homicide-suicide in older personsAmerican Journal of Psychiatry15539069501751

- ConwellYDubersteinPRConnorK2002Access to firearms and risk for suicide in middle aged and older adultsAmerican Geriatric Psychiatry1040716

- GillespieMHearnVSilvermanRA1998Suicide following homicide in CanadaHomicide Studies24663

- JohnsonHHottonT2003Losing control: Homicide risk in estranged and intact intimate relationshipsHomicide Studies75884

- JohnsonMFerraroKJ2000Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: making distinctionsJournal of Marriage and Family6294863

- Kyodo World News Service2004More people killed from suicide than war: WHO9/9/2004.

- LescoPA1989Murder-suicide in Alzheimer’s diseaseJournal of the American Geriatrics Society3716782642936

- Lefevre-SillitoCSalariS2006Murder suicide: Couple characteristics, child outcomes and community impact 1999–2004International Conference on Violence, Abuse and TraumaSan Diego, CASeptember 17

- MalphursJECohenD2002A newspaper surveillance study of homicide-suicide in the United StatesAmerican Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology23142812040257

- MalphursJECohenD2005A statewide case-control study of spousal homicide-suicide in older personsAmerican Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry132111715728752

- MalphursJEEisdorferCCohenD2001Comparison of antecedents of homicide-suicide and suicide in older married menAmerican Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry9495711156752

- MarzukPMTardiffKHirschCS1992The epidemiology of murder-suicideJAMA2673179831593740

- MaxMBLynnJSelected qualitative methods, Ch 7 in Symptom research: Methods and opportunitiesInteractive textbook. http://painconsortium.nih.gov

- MayringP2000Qualitative content analysisForum: Qualitative Social Research, Online Journal 1(2). http://qualitative-research.net/fqs/fqs-e/2-00inhald-e.htm Accessed 3/20/06.

- National center for health statistics2004NCHS data on agingCenters for disease control and preventionhttp://cdc.gov/nchs

- O’ConnellHOChinACunninghamC2004Recent developments: Suicide in older peopleBritish Medical Journal329895915485967

- Reuters Health1999Demented patients often have access to loaded guns. Reviews Spangenberg et al research published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.105http://reutershealth.com

- RichmanJ2001–2002Family therapy with elderly suicidal patients: Communication and crisis aspectsOmega: Journal of Death and Dying4436170

- RosenbaumM1990The role of depression in couples involved in murder-suicide and homicideAmerican Journal of Psychiatry147103692375438

- SalariS2005Murder-suicide patterns and comparisons for middle aged and elderly intimate partners: 1999–2005Paper presentation Gerontological society of America annual meeting11Orlando, FL

- SalariS2006Infantilization as elder mistreatment: evidence from 5 adult day centersJournal of Elder Abuse and Neglect174

- SalariSBaldwinBM2002Verbal, physical and injurious couple aggression over timeJournal of Family Issues2352350

- SalariSLefevre-SillitoC2006Content analysis of intimate partner murder-suicide reports: comparing perpetrator intent in 3 age groupsPresentation Gerontological society of America annual meeting11Dallas TX

- SalariSZhangW2006Kin keepers and good providers: Gender socialization effects on well-being among birth cohortsAging and Mental Health104859616938684

- The Virginian Pilot2000Murder-suicide “cluster” recorded recently in Virginia24 Jul 2000.

- US Department of Justice2001Intimate partner violence and age of victim, 1993–1999[online]Bureau of justice statistics: Special report112Washington D.CURL: http://www.vpc.org

- Violence Policy Center VPC2002American roulette: The untold story of murder-suicide in the United States

- Washington state coalition against domestic violence2003Tell the world what happened to me: Findings and recommendations from the Washington state domestic violence fatality review. December 2002.

- WebsdaleN2000Lethality assessment tools: A critical analysis. VAWnet applied research forum. National resource center on domestic violence17