Abstract

Falls in the elderly are an important independent marker of frailty. Up to half of elderly people over 65 experience a fall every year. They are associated with high morbidity and mortality and are responsible for greater than 20 billion dollars a year in healthcare costs in the United States. This article presents a review and guide for the primary care provider of the predisposing and situational risk factors for falls; comprehensive assessment for screening and tailored intervention; and discussion of single and multicomponent measures for fall prevention and management in the older person living in the community. Interventions for the cognitively impaired and demented elderly will also be addressed.

Keywords:

Introduction

Falls have been recognized for decades by health care professionals as an etiology for injury, but were not seen as an important independent marker of frailty until more recently. They are associated with a high mortality that is not always explainable by the fall injury itself (CitationTinetti et al 1995). For good reason, today it is considered a health problem on its own and a unique geriatric syndrome.

This article discusses nonsyncopal falls, that is, falls that are not associated with a loss of consciousness, stroke or seizure, nor related to a violent blow. While the etiology and risk factors for falls may be similar in the community and nursing home, the relative frequencies and interventions are different in these populations. This article will focus on the older patient in the community.

It is important to understand that many of these falls are multifactorial in origin and do not result from one intrinsic or extrinsic cause. However, many nonsyncopal falls in the older adult occur when environmental hazards or demands outweigh the individual’s ability to maintain postural stability. While children and athletes have an even higher incidence of falls than the elderly, the elderly have a higher susceptibility to injury which makes their falls so devastating (CitationAmerican Geriatrics Society et al 2001).

Often because they believe falls are a normal part of aging or because they have never fallen, older persons do not realize the risk factors for falls and may never report them to their physicians if they do occur. If the physician does not specifically screen for falls, there is a missed opportunity to prevent future incidents.

This article examines the prevalence of falls, the most common risk factors for falls and the steps involved in patient evaluation. Identifying those at risk for falls and evaluating a patient after a fall will also be discussed. Lastly, recommendations for therapeutic and preventative approaches will be offered.

Prevalence and morbidity

In persons over 65 years old, 35%–45% of community-dwelling adults report a fall every year (CitationAmerican Geriatrics Society et al 2001). However, in those over 80 years old who live in the community, 50% fall each year (CitationO’Loughlin et al 1993; CitationBlake et al 1998; CitationTinetti et al 1998). Of those, half will go on to fall a second time.

Although only 20% seek immediate medical attention because of the fall, only 5% of those result in fracture and 5%–10% in other serious injury (CitationKannus et al 2005). At the same time, 40% of hospital admissions of those over 65 years old are reported to be the result of falls (CitationSattin et al 1990). The consequences of falls among older adults are often devastating. One-half of elderly admitted to the hospital for a fall-related injury are discharged to a long-term care institution (CitationSattin et al 1990). Recurrent falls are also a common reason for admission to long-term care institutions (CitationAmerican Geriatrics Society et al 2001).

Falls that do not result in injury often begin a downward cycle of fear that leads to inactivity and decreased strength, agility, and balance. In the worst case, this can lead to loss of independence, including long-term care placement. 25%–55% of older persons fear falling, and of those who have fear, another 20–55% restricts their activities because of this fear (CitationMurphy et al 2003).

Unintentional injury is the 5th leading cause of death in person over age 65 and two-thirds of those are due to falls and their complications (CitationAmerican Geriatrics Society et al 2001). The cost of falls to society is enormous. In 1994 the total costs for injurious falls including hospitalizations, surgery and recovery among others was $20.2 billion dollars, and is projected to reach 32.4 billion (in 1994 US dollars) by 2020 (CitationChang et al 2004).

Risk factors

The ability to maintain one’s stability is dependent on the intricate functioning of sensory, central integrative and musculoskeletal effector components (CitationThomas et al 2003). As one ages, there are cumulative impairments and diseases which are superimposed on age-related physiologic changes whose ultimate aggregation may result in a fall (CitationWolfson et al 1985). As a result, falls often serve as a nonspecific marker for an underlying disease or a disability and may be the only indicator to the health care practitioner of an acute illness or a worsening of a chronic disease. For example, an acute febrile illness, such as a community acquired pneumonia or a urinary tract infection, may precipitate a fall by impairing stability and decreasing one’s ability to maintain the intricate balance needed to avoid a fall (CitationTinetti et al 1988).

A clinically useful method for explaining the etiology of falls is to consider both the predisposing and situational risk factors. Predisposing risk factors are the intrinsic characteristics of the person that chronically impair stability and may make them more easily fall. The situational risk factors are those host, activity and environmental factors that are present at the time of the fall. In one-third of falls, the environment is considered the major risk factor; about 17% of falls cite gait and balance as the primary risk and dizziness in 13% of falls (CitationRubenstein et al 2001).

Looking at over 60 recent studies of risk factors for falls, over 25 different risk factors can be identified. It has also been shown that there is a linear relationship between the number of risk factors a person has and their likelihood for falls (CitationTinetti and Speechley 1989). In addition to predisposing and situational risk factors for falls, it has been found that increasing age and previous falls put one at higher risk for recurrent falls (CitationAmerican Geriatrics Society et al 2001).

Predisposing risk factors

Sensory

The primary sensory modalities, which are responsible for orienting a person in space, are the sensory, hearing, vestibular and proprioceptive systems. These systems require a delicate interaction in order to provide the necessary inputs to maintain ones stability. It is visual acuity, contrast sensitivity and depth perception (involved in spatial orientation) that are most relevant to maintaining postural stability and avoiding a fall (CitationGlynn et al 1991; CitationLord et al 1994). Bifocal glasses are problematic for those at risk of falls because when something happens to cause a fall, the person is unable to focus on their feet and the ground surface to stabilize themselves as they look down through the reading portion of the bifocals.

Hearing directly affects stability by the detection and interpretation of auditory stimuli which help orient a person in space. Greater than 50% of older people have some degree of hearing loss (CitationWoolf et al 1990). The vestibular system assists with spatial orientation at rest and with acceleration, and maintains visual fixation during head and body movements. The proprioceptive systems provide for spatial orientation during position changes, while walking on uneven surfaces or when other systems are impaired (CitationTinetti 1989). Patients with impairment in any of these systems will have worsened stability in the dark due to the greater reliance on visual input.

Central nervous system

Due to the complicated nature and interaction of the central nervous system and other systems necessary for stability, many disorders or diseases which affect this system may predispose an older patient to a fall. Diseases with obvious physical impairments (cerebrovascular accident, Parkinson’s disease) have increased risk of falls, as do diseases such as dementia, which have a negative effect on cognition (by adversely affecting problem solving and judgment). In addition, even white matter disease with no effect on cognition has been associated with a gait disorder (CitationMasdeu et al 1989).

Musculoskeletal

Any impairment of the musculoskeletal system including bones, joints or muscles/tendons may have an adverse affect on stability (CitationWhipple et al 1987). Any of the arthritides may increase the likelihood of a fall through multiple mechanisms, including pain, muscle weakness or decreased proprioception. Abnormalities of the foot should also be mentioned, as calluses, bunions or toe and nail deformities can lead to poor gait (secondary to decreased proprioception).

Medications

The relationship between medications and falls has been documented in various studies. These include such prescription medications as sedative-hypnotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics and cardiovascular agents like digoxin, type 1A antiarrhythmics and diuretics. (CitationRay et al 1990; CitationCumming 1998; CitationLeipzig et al 1999a, Citation1999b). In addition, the use of four or more medications and changes in dose have also been shown to be associated with falling (CitationRobbins et al 1989). Alcohol has also been associated with falls even in low doses (CitationNelson et al 1992). These effects may by due to multiple factors such as impairment of cognition, postural hypotension, dehydration, fatigue, or electrolyte disturbances.

Postural hypotension

Postural hypotension may result in a fall by compromising the cerebral blood flow (CitationLipsitz 1989). This condition affects 10% to 30% of older patients living in the community. It is often multifactorial in origin and such things as comorbidities and medications used to treat them are superimposed on age-related physiologic changes present in the older patient (eg, autonomic changes, decreased baroreceptor sensitivity).

Situational risk factors

Most falls occur during normal, non-hazardous activity in the community living older person. These include such activities as walking, changing position or performing basic activities of daily living. Hazardous activities such as climbing on ladders, standing on an unstable surface or playing sports account for a very small percentage of falls (CitationTinetti et al 1988).

The majority of falls in persons living in the community are probably due to environmental factors. Greater than 70% of falls in the community occur in the home. Approximately 10% of falls occur on stairs which represents a high percentage since it is out of proportion of time spent on them. Of these, descending is more hazardous than ascending (CitationTinetti et al 1988; CitationStartzell et al 2002). The literature reports that carrying heavy or bulky objects, slippery floors, and poor lighting are the most common environmental hazards associated with falls (CitationStevens et al 2001). Patterns on floors or walls may also be a potential hazard since they may either distort or improve visual perception (CitationOwen 1985). Of note, in nonambulatory older persons, falls are more likely to occur during transfers or due to faulty or improperly fitting equipment (CitationThapa et al 1996). Another potential hazard is the use of poorly fitting or slippery shoes.

Evaluation after a fall

History

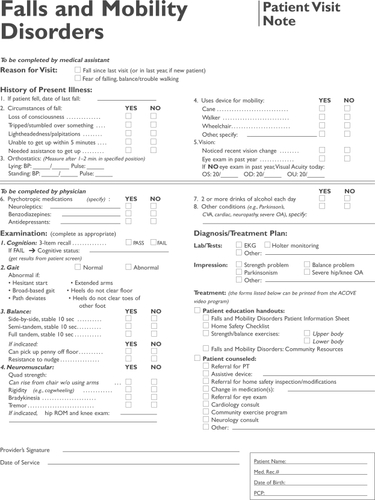

It is critical to begin an evaluation of a fall with a careful history and physical examination. This examination could be in the acute setting if the patient presents immediately after a fall, or at the next office visit when the patient reports or the physician screens for recent incidents. The assessing care of vulnerable elders (ACOVE) project has created a series of forms for use by practicing internists in treating geriatric syndromes. The project initially looked at quality indicators using an evidence-based approach, and was overseen by a panel of experts (CitationRubenstein et al 2001; CitationShekelle et al 2001; CitationWenger and Shekelle 2001). Falls were one of the topics addressed, and is an example of one such form and is useful for reference (CitationACOVE 2006).

It is important to take a thorough history of all possible contributing factors to the fall. First, care should be taken to investigate the time period just prior to the event and then what happened as a result of the fall: was there loss of consciousness, tripping or stumbling, lightheadedness or palpitations; did the patient have any difficulty getting up? Next, a careful review of the major risk factors needs to be completed: what medical problems do they have such as Parkinson’s, strokes, cardiac, neuropathy, severe osteoarthritis or dementia? A thorough review of medications with specific attention to recent changes or adjustments is also prudent, with a focus on vasodilators, diuretics and sedative hypnotic drugs. Determining whether an assistive device is ever used, even if it is only outside the house, is also helpful. These assistive devices are often used incorrectly or the device is the wrong height. Use of an assistive device has been shown in multiple studies to be associated with an increased risk of falling (CitationAmerican Geriatrics Society et al 2001). Lastly, asking about their vision and alcohol use is important in understanding all possible causes.

Physical exam

The physical exam should focus on gait, balance and strength, in addition to the neurologic and cardiac exams. To start, all patients after a fall need to have orthostatic vital signs taken, as some never report symptoms. In addition, if a patient has not had an eye exam in the last year the visual acuity should be measured. The cardiac exam should include auscultation and palpation of the heart for murmurs and cardiac rhythm. The carotid arteries should also be examined for bruits. During the neurologic examination symmetry in strength is important to look for. Rigidity or cogwheeling, bradykinesia or tremor may raise suspicion for Parkinsonism. Examination of the feet for neuropathy and of the joints for arthritis is also important to evaluate. Cognitive impairment and dementia should be evaluated with the use of a simple test such as the three item recall.

The largest portion of the physical exam should focus on the gait, balance and quadriceps strength. Gait and strength are quickly and easily examined using the “Get Up and Go” test, where the patient is instructed to rise from a seated position without the use of their arms (quadriceps strength) and walk 10 feet, turn, and sit back down (CitationMathuas et al 1986; CitationPodsiadlo and Richardson 1991). In observing the gait, the practitioner should look for any hesitant starts, broad-based gait, extended arms, whether the path deviates and if the heels do not clear the floor. This test is often timed, and different cut off times exist for different indications. In this setting, where the provider is trying to identify the major or multiple causes of the fall, the end result is to be able to tailor the treatment plan by identifying abnormalities in gait or stature, so timing is not as critical.

Many different tests exist for balance. One quick and easy balance test is to check the ability of the patient to hold three poses, each for 10 seconds: first feet side by side, then semi-tandem, and finally tandem. Other balance tests involve more performance-oriented tasks like picking a penny off the floor, or being able to resist a nudge when standing with two feet together. A more comprehensive test for balance is the performance-oriented mobility assessment of balance (B-POMA), which includes measures of sitting and standing balance, the ability to withstand a nudge on the sternum, and the ability to reach up, bend down, and extend the back.

Another test that is often employed is the “functional reach” test which measures neuromuscular base of support (both balance and quad strength). It requires a yardstick to be leveled at the height of the acromion and the person to reach as far forward without falling or taking a step.

None of these tests have been shown to be a superior measure of balance problems, and different groups have recommended different tests. ACOVE recommends evaluating the older person using the three poses ending with tandem stance.

Laboratory evaluation

No laboratory or other tests have been shown to be useful in general for the evaluation of falls. However, if a patient presents acutely after a fall, a more through laboratory examination might be performed. Especially if the history or physical exam suggests an underlying issue, then the appropriate tests should be undertaken. However, if a patient is being evaluated for a fall that occurred further in the past, then little or no laboratory examination needs to be performed.

History and examination for those at risk for falls

The American Geriatrics Society position statement recommends that clinicians who care for older persons ask about falls annually. If a patient reports a single fall, then a balance and gait screening should be performed using the “Get Up and Go” test. If there is any difficulty in this testing, then further assessment and intervention is required (CitationAmerican Geriatrics Society et al 2001). In the newer guidelines presented at the 2006 American Geriatrics Society meeting, the screening questions by clinicians are expanded to include: (1) recurrent falls, (2) difficulty walking or balance, (3) fear of falling, and (4) presentation with an acute fall. If any of these are positive, then the patient should have a comprehensive assessment as described above.

There have been multiple studies to evaluate different tests for gait, balance and strength to identify the most effective screening test. There is very good evidence that a balance and gait assessment is the best way to identify those at risk for falls (CitationNevitt et al 1989), but the choice of test for performing this assessment is not so clear.

Some tests such as the berg balance scale (BBS) and fast evaluation of mobility, balance and fear (FEMBAF) take up to 20 minutes to complete. Therefore, those tests are difficult to apply clinically. There are four tests that are commonly used and each take less than 5 minutes to complete: the functional reach test (FRT), which has been shown to have predictive validity in elderly males (CitationDuncon et al 1992), the one-leg stance test (OLST), timed get up and go test (TUG), and the balance portion of the performance oriented mobility assessment (B-POMA) which is the longest of the four to complete. All have reasonable inter-rater reliability. Comparing these tests in frail elders and then retrospectively looking to see which elders had fallen, one study found that the OLST and the B-POMA both had statistically significant differences between fallers and non-fallers. The OLST had sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 89% using a 1.02 second cut-off and the B-POMA had an 83% sensitivity and a 72% specificity using a score of 11 (CitationThomas and Lane 2005).

Since there is no consensus as to the exact test to use, it is most important to ask about falls or fear of falls and then do as simple a test in the office as possible to screen for those at risk in order to formulate a prevention strategy.

Management and prevention of falls

After a thorough assessment is made of the patient’s medical, predisposing and situational risk factors for falls, several interventions are available to providers to manage and prevent future falls. This section will review current trials and new evidence for interventions aimed at fall management and prevention for elderly people living in the community. Measures to prevent and manage falls risks in community-dwelling elderly with cognitive impairment will also be discussed.

Single interventions

Exercise: strength, gait, and balance training

Strength and balance training improve many falls risk factors, including muscle strength, flexibility, coordination, balance, proprioception, reaction time and gait. Almost without exception, there has been benefit of strength and balance training for the elderly living in the community. A large review of trials showed a risk reduction in both non-injurious and injurious falls of 15%–50% over a maximum of two years, and was seen regardless of whether the study employed tailored training or untargeted group interventions (CitationKannus et al 1999). These improvements have been shown even in trials involving the very old and frail. Exercises focused on balance, such as Tai Chi, seem to be especially helpful (CitationBuchner et al 1993; CitationLi et al 2005). The most recent Cochrane pooled analysis of the same trials, however, found a reduction in the number of falls only in targeted interventions for community-dwelling elderly, and no benefit in untargeted interventions for similar populations (CitationRobbins et al 1989; CitationGillespie et al 2003).

Of note, two trials of focused exercise interventions showed negative results. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of women with a known history of falls and fracture showed an increase in falls in the group assigned to a brisk walking regimen (CitationEbrahim et al 1997). Another examined the effects of focused, progressive quadriceps training in 222 frail elderly. Although there was no difference in subsequent falls between the two groups, the intervention group sustained significantly more musculoskeletal injuries (CitationLatham et al 2003). Therefore, these focused programs should not be recommended in patients who are frail, elderly, or have a prior history of falls.

Although more research is needed to determine the optimum intensity, type, frequency and duration of exercise that is most clinically and cost effective, it can be recommended that regular strength and balance training, preferably tailored to the patient, be prescribed for the general elderly population. Especially given the relative economy, safety, availability and ease of implementation of an exercise regimen, it remains a mainstay of combination falls prevention strategies to both prevent falls and maintain musculoskeletal conditioning.

Environmental assessment and modification

Environmental assessment and modification can be done by the healthcare provider, but is most often performed by the physical therapist making visits to the home as part of a plan for personalized gait or balance training. In addition to prescribing and ensuring adequate use of assistive devices by the person at risk for falls (eg, canes, walkers, shoes), a home hazard assessment can clarify other environmental modifications that need to be made. Improving lighting and floor treatments (eg, higher wattage bulbs, nightlights, less resistant flooring, removing loose rugs) and changing furniture (higher chair seats with arms for support, increased bed height without siderails, raised toilet seats) are all thought to reduce falls at home from extrinsic causes (CitationKannus et al 1999; CitationThomas et al 2003).

A Cochrane review of five randomized trials showed that home hazard assessment and modification of the living environment professionally prescribed for people with a history of falls resulted in a risk reduction in recurrent falls during the study period of 33% (CitationGillespie et al 2003). Environmental assessment and modification, however, was not shown to be effective in older people without a history of falling. Therefore, this intervention should be recommended in those patients with known history of falls in order to prevent future falls.

Medication assessment and management

It is well-established that in the elderly, multiple medications (eg, psychotropics, sedatives, anxiolytics, antidepressants, blood pressure medications, anticholinergics), both singly and in combination, are associated with increased falls risk (CitationLeipzig et al 1999a, Citation1999b; CitationWoolf and Akesson 2003). Falls in association with other symptoms (eg, dizziness, orthostasis, sedation) are also cited as one of the most common adverse drug events in the elderly. It seems prudent that careful review and limiting of medications that are associated with falls is in good practice for elderly patients with and without a history of falling.

One randomized trial in 1999 showed that by the gradual withdrawal of antipsychotic medication in combination with an exercise program, a 66% risk reduction of falls was seen (CitationCampbell et al 1999). Although no trials examine medication reduction alone, multifactorial interventions which include medication reduction showed a reduction in risk for falls for older adults (CitationGillespie et al 2003).

Assessment and management of visual impairments

There is insufficient evidence to recommend vision evaluation as a single intervention for falls prevention. However, current AGS guidelines generally accept that screening for visual impairment followed by appropriate management should be part of the multifactorial assessment for falls, as visual impairment is known to greatly increase fall risk and several trials which include vision intervention showed positive overall results. Vision interventions range from baseline vision testing to vision correction and counseling regarding the appropriate use of multifocal lenses, to cataract surgery if indicated (CitationLord et al 1991; CitationClemson et al 2004; Citationde Boer et al 2004; CitationCampbell et al 2005).

A recent randomized trial of elderly women with first cataract showed that compared to delayed-surgery controls, expedited surgery resulted in a 34% reduced rate of fall (CitationHarwood et al 2005). Explanations for this are thought to be early cataract surgery leading to improvements in visual function, confidence, activity level, functional disability and anxiety. If further studies support this finding, recommendation of early cataract surgery may become a widespread intervention in this population of elderly in which cataracts are a common condition.

Prevent fall-related injuries

Calcium and vitamin D, treatment of osteoporosis

Maximizing peak bone mass and preventing bone loss through regular weight-bearing physical activity, calcium and vitamin D, with appropriate treatment of osteoporosis is standard of care and prevents fracture. This information is vast and well-established and is not the focus of this review.

Hip protectors

A Cochrane review of hip protector use in 14 randomized trials concluded that this intervention may be most protective in reducing fracture risk in high-risk elderly people (CitationParker et al 2004). The review showed no benefit in using hip protectors in elderly at low risk for falls. However, limitations of its use, including lack of head-to-head comparisons between different models and poor user adherence make this a suboptimally studied and used intervention. More research is needed before wide recommendations can be made regarding its use.

Diagnose and manage postural hypotension and cardioinhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity

Postural or orthostatic hypotension is a significant iatrogenic and primary risk factor for falls, and checking for orthostasis is a standard component for falls risk factor assessment. Management of postural hypotension includes several modalities such as limiting offending drugs, ensuring adequate hydration and salt intake, employing rehabilitative and reconditioning techniques (graded pressure-stockings, dorsiflexion/hand flexion before arising, slow position changes), and elevation of head of the bed. Starting an exercise regimen may also improve postural hypotension (CitationThomas et al 2003).

Separate from and less prevalent than orthostatic hypotension, cardioinhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity can result in hypotension, bradycardia, paroxysmal asystole, syncope and subsequent falls. The SAFE PACE I trial examined the effect of pacemaker placement in older adults with this syndrome and saw a significant 58% reduction in falls and 70% reduction in fall-related injury in those elderly adults with this condition who received cardiac pacemakers (CitationKenny et al 2001). Unfortunately, clear cut benefit was not seen in frailer and cognitively impaired patients receiving pacemakers in the ongoing SAFE PACE II trial (CitationBrignole 2004); more research will be needed in this high-risk group.

Vitamin D supplementation

In addition to the known benefit of calcium and vitamin D in improving bone mass and preventing osteoporotic fractures, Vitamin D alone may prevent falls by alleviating muscle atrophy and improving musculoskeletal function and performance (CitationGillespie et al 2003). This effect may be enhanced by co-supplementation with calcium. However, available trials are heterogeneous and conflict significantly in their results. The largest randomized trials show no benefit of vitamin D supplementation on falls or falls-related fractures (CitationPorthouse et al 2005; CitationRecord Trial Group 2005). Pooled analyses of smaller trials do not show an overall benefit in falls reduction (CitationGillespie et al 2003).

It is currently unclear whether vitamin D can prevent falls or fractures related to falls. The optimum dosing and type of vitamin D and calcium supplementation for improving muscle function is also still unknown. However, because of its relatively easy and widely accepted use for osteoporosis prevention and treatment in the same population of patients, it is reasonable to recommend this treatment for elderly people at high risk for deficiency in these substances (eg, institutionalized or homebound frail elderly).

Multicomponent interventions

The multifactorial intervention strategy for falls prevention includes risk factor assessment and management of identified risk factors for community-dwelling older adults without known cognitive impairment. Theoretically, a multifactorial intervention should be more effective than a single intervention, given that the causes and risk factors for falls in older adults are often numerous and interwoven (CitationThomas et al 2003). Several randomized trials have shown, and systematic reviews and meta-analyses support, that multi-intervention strategies can prevent falls in community-dwelling, cognitively intact elderly adults by 20%–45% at both high and low risk for falls (CitationKannus et al 1999; CitationGillespie et al 2003). Unfortunately, this benefit was not shown in cognitively impaired patients (CitationJensen et al 2003; CitationShaw et al 2003).

The content of each multifactorial intervention program varies considerably between studies, including type and duration of exercise (strength, balance, gait training), physical therapy, footwear improvements, management of medical comorbidities and medications, vision assessments and treatments, hip protectors, staff and patient education, and environmental modification components (CitationKannus et al 2005). The trials using a “tailored” approach of offering participants only the interventions targeted toward their known set of risk factors seem to be the most logical and cost-effective. As such, general guidelines for falls prevention recommend using effective single-interventions as the components of a tailored multifactorial approach (CitationGillespie et al 2003; CitationTinetti 2003).

It should be noted that there are several limitations and difficulties in implementing multicomponent interventions to prevent falls in the elderly, including the requirement of these programs for multidisciplinary expertise and staffing, and ongoing issues with coordination and reimbursement. The current literature provides insufficient evidence of which components are essential and which, if any, are effective in cognitively impaired populations.

In summary, multicomponent interventions are better than any single intervention. Benefit from any intervention is seen most in those with history of falling than those at low-risk for falls. Single interventions found to be effective and are therefore recommended as part of tailored falls prevention regimens are balance/strength exercise training, environmental modification, medication management, early vision assessment and treatment (especially cataracts), appropriate footwear, and medical therapy of osteoporosis. Promising interventions that still need further study are early cataract surgery, cardiac pacing for those with cardioinhibitory carotid sinus hypersensitivity, and vitamin D supplementation with calcium for improved muscle function separate from osteoporosis prevention.

Special populations of community living elderly

Cognitively impaired and demented elderly

Patients with cognitive impairment and dementia are at increased risk for falls due to several intrinsic and extrinsic factors including postural and neurocardiovascular instability, medication use, and type of dementia. The few studies examining multifactorial interventions to prevent falls in this population have not shown a reduction in falls (CitationJensen et al 2003; CitationShaw et al 2003). The lack of benefit may be due to inability of demented patients to learn and remember new information and/or comply with prolonged exercise regimens. More studies are needed to see if any components of a multifactorial intervention are likely to be of benefit in this vulnerable and challenging population.

Conclusion

Falls in community-living elders is an important geriatric syndrome and are a major source of morbidity and mortality. Primary care providers are uniquely set up to provide a systematic and thorough evaluation of all older adults for their risk of falls. This should include an annual screening for falls with an assessment of predisposing and situational risk factors complete with history, physical exam, and if possible, a home safety evaluation. Primary care providers should also refer to other health care professionals such as ophthalmologists, optometrists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, podiatrists, social workers and nurses to aid them in evaluating risk factors and to coordinate and manage optimally tailored interventions for their patients.

References

- [ACOVE] Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders™ physician education program2006RAND Health—American Geriatrics Society—Pfizer

- American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopedic surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention2001Guideline for the prevention of falls in older personsJ Am Geriatr Soc496647211380764

- BlakeAMorganKBendallM1988Falls by elderly people at home: prevalence and associated factorsAge Ageing17365723266440

- BrignoleM2004Cardiovascular risk factors for falls in older peopleinternational symposium on preventing falls and fractures in older peopleYokohama, JapanJune 29–July 12004

- BuchnerDMCressMEWagnerEH1993The Seattle FICSIT/MoveIt study: the effect of exercise on gait and balance in older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc4132158440857

- CampbellAJRobertsonMCGardnerMM1999Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home-based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trialJ Am Geriatr Soc47850310404930

- CampbellAJRobertsonMCLaGrowSJ2005Randomized controlled trial of prevention of falls in people aged ≥75 with severe visual impairment: the VIP trialBMJ33181716183652

- ChangJMortonSRubensteinL2004Interventions for the prevention of falls in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trialsBMJ328680715031239

- ClemsonLCummingRGKendigH2004The effectiveness of a community-based program fro reducing the incidence of falls in the elderly: a randomized controlled trialJ Am Geriatr Soc5314879415341550

- CummingRG1998Epidemiology of medication-related falls and fractures in the elderlyDrugs Aging1243539467686

- de BoerMRPluijmSMLipsP2004Different aspects of visual impairment as risk factors for falls and fractures in older men and womenJ Bone Miner Res1915394715312256

- DunconPStudenskiSChandlerJ1992Functional reach: Predictive validity in a sample of elderly male veteransJ Gerontol47M931573190

- EbrahimSThompsonPWBaskaranV1997Randomized placebo-controlled trial of brisk walking in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosisAge and Aging2625360

- GillespieLDGillespieWJRobertsonMC2003Interventions for preventing falls in elderly peopleCochrane Database Syst Rev4

- GlynnRJSeddonJMKrugJHJr1991Falls in elderly patients with glaucomaArch Ophthalmol109205101993029

- HarwoodRHFossAJOsbornF2005Falls and health status in elderly women following first eye cataract surgery: a randomized controlled trialBr J Ophthalmol8953915615747

- JensenJNybergLGustafsonY2003Fall and injury prevention in residential care – effects in residents with higher and lower levels of cognitionJ Am Geriatr Soc516273512752837

- KannusPParkkariJKoskinenS1999Fall-induced injuries and death among older adultsJAMA28118959910349892

- KannusPSievanenHPalvanenM2005Prevention of falls and consequent injuries in elderly peopleLancet36618859316310556

- KennyRARichardsonDASteenN2001Carotid sinus syndrome: a modifiable risk factor for nonaccidental falls in older adults (SAFE PACE)J Am Coll Cardiol381491611691528

- LathamNKAndersonCSLeeA2003A randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: The frailty interventions trial in elderly subjects (FITNESS)J Am Geriatr512919

- LeipzigRMCummingRGTinettiME1999aDrugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Psychotropic drugsJ Am Geriatr Soc473099920227

- LeipzigRMCummingRGTinettiME1999bDrugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Cardiac and analgesic drugsJ Am Geriatr Soc4740509920228

- LiFHarmerPFisherKJ2005Tai chi and fall reductions in older adults: a randomized controlled trialJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci601879415814861

- LipsitzLA1989Orthostatic hypotension in the elderlyN Engl J Med32195272674714

- LordSRClarkRDWebsterIW1991Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity in relation to falls in an elderly populationAge and Aging2017581

- LordSRWardJAWilliamsP1994Physiological factors associated with falls in older community-dwelling womenJ Am Geriatr Soc42111077930338

- MasdeuJCWolfsonLLantosG1989Brain white-matter changes in the elderly prone to fallingArch Neurol46129262590013

- MathiasSNayakUIsaacsB1986Balance in elderly patients: the “get up and go” testArch Phys Med Rehabil6738793487300

- MurphySDubinJGillT2003The development of fear of falling among community-living older women: predisposing factors and subsequent fall eventsJournal of Gerontology58A9437

- NelsonDESattinRWLangloisJA1992Alcohol as a risk factor for fall injury events among elderly persons living in the communityJ Am Geriatr Soc40658611607580

- NevittMCummingsSKiddS1989Risk factors for recurrent nonsyncopal falls. A prospective studyJAMA261266382709546

- O’LoughlinJRobbitailleYBoivinJ1993Incidence of and risk factors for falls and injurious falls among community-dwelling elderlyAm J Epidemiol137342548452142

- OwenDH1985Maintaining posture and avoiding tripping. Optical information for detecting and controlling orientation and locomotionClin Geriatr Med1581993913510

- ParkerMJGillespieLDGillespieWJ2004Hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in the elderlyCochrane Database Syst Rev3CD00125515266444

- PodsiadloDRichardsonS1991The timed “ up & go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly personsJ Am Geriatr Soc3914281991946

- PorthouseJCockayneSKingC2005Randomized controlled trial of supplementation with calcium and cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) for prevention of fractures in primary careBMJ3301003615860827

- RayWAGriffinMRShorrRI1990Adverse drug reactions and the elderlyHealth Aff911422

- The RECORD trial group2005Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low-trauma fractures in elderly people (Randomized evaluation or vitamin D, RECORD: a randomized placebo-controlled trial)Lancet3651621815885294

- RobbinsASRubensteinLZJosephsonKR1989Predictors of falls among elderly people. Results of two population-based studiesArch Intern Med1491628332742437

- RubensteinLJospehsonK2002The epidemiology of falls and syncopeClin Geriatr Med181415812180240

- RubensteinZLPowersCMacLeanD2001Quality indictors for the management and prevention of falls and mobility problems in vulnerable eldersAnn Intern Med1356869311601951

- SattinRLambertHDevitoC1990The incidence of fall injury events among the elderly in a defined populationAm J Epidemiol1311028372343855

- ShawFEBondJRichardsonDA2003Multifactorial intervention after a fall in older people with cognitive impairment and dementia presenting to the accident and emergency department: randomized controlled trialBMJ32673812521968

- ShekellePMacLeanCMortonS2001ACOVE quality indicatorsAnn Intern Med1356536711601948

- StartzellJKOwensDAMulfingerLM2002Stair negotiation in older people: a reviewJ Am Geriatr Soc485678010811553

- StevensMHolmanCDBennettN2001Preventing falls in older people: impact of an intervention to reduce environmental hazards in the homeJ Am Geriatr Soc491442711890581

- ThapaPBBrockmanKGGideonP1996Injurious falls in nonambulatory nursing home residents: a comparative study of circumstances, incidence, and risk factorsJ Am Geriatr Soc4427388600195

- ThomasDCEdelbergHKTinettiME2003FallsCasselCKGeriatric Medicine: an evidence based approach4th edNew YorkSpringer97994

- ThomasJLaneJ2005A pilot study to explore the predictive validity of 4 measures of falls risk in frail elderly patientsArch Phys Med Rehabil8616364016084819

- TinettiMSpeechleyNGinterS1988Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the communityN Eng J Med31917017

- TinettiMEInstability and falling in elderly patients. 1989Semin Neurol939452756252

- TinettiMESpeechleyM1989Prevention of falls among the elderlyN Engl J Med320105592648154

- TinettiMInouyeSGillT1995Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromesJAMA2731348537715059

- TinettiME2003Preventing falls in elderly personsN Engl J Med34842912510042

- WengerNShekelleP2001Assessing care of vulnerable elders: ACOVE project overviewAnn Intern Med135642611601946

- WhippleRHWolfsonLIAmermanPM1987The relationship of knee and ankle weakness to falls in nursing home residents: an isokinetic studyJ Am Geriatr Soc3513203794141

- WolfsonLIWhippleRAmermanP1985Gait and balance in the elderly. Two functional capacities that link sensory and motor ability to fallsClin Geriatr Med1649593913514

- WoolfADAkessonK2003Preventing fractures in elderly peopleBMJ327899512855529

- WoolfSHKamerowDBLawrenceRS1990The periodic health examination of older adults: The recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force. Part II. Screening testsJ Am Geriatr Soc38933422387958