Abstract

As our society ages, increasing numbers of older Americans will be diagnosed and eventually will die of cancer. To date, psycho-oncology interventions for advanced cancer patients have been more successful in reaching younger adult age groups and generally have not been designed to respond to the unique needs and preferences of older patients. Theories and research on successful aging (Baltes and Baltes 1990; Baltes 1997), health information processing style (Miller 1995; Miller et al 2001) and non-directive client-centered therapy (Rogers 1951, 1967), have guided the development of a coping and communication support (CCS) intervention. Key components of this age-sensitive and tailored intervention are described, including problem domains addressed, intervention strategies used and the role of the CCS practitioner. Age group comparisons in frequency of contact, problems raised and intervention strategies used during the first six weeks of follow up indicate that older patients were similar to middle-aged patients in their level of engagement, problems faced and intervention strategies used. Middle-aged patients were more likely to have problems communicating with family members at intervention start up and practical problems as well in follow up contacts. This is the first intervention study specifically designed to be age sensitive and to examine age differences in engagement from the early treatment phase for late-stage cancer through end of life. This tailored intervention is expected to positively affect patients’ quality of care and quality of life over time.

Introduction

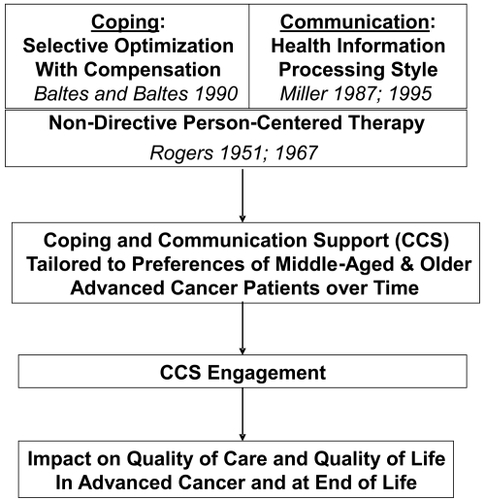

This paper describes our development of a coping and communication support (CCS) intervention for advanced cancer patients. Key components of this age-sensitive and tailored intervention are described, including problem domains addressed, intervention strategies used and the role of the CCS practitioner. Preliminary data on similarities and differences in middle-aged and older patients’ initial problems, preferences and engagement in the intervention are reported. Although family caregivers are an integral part of our intervention study, this article reports only on patients. The CCS intervention is implemented with newly diagnosed late-stage cancer patients who are middle-aged and older. It is tailored to patients’ needs and preferences and designed to support them over the period of time when life goals and care goals are expected to shift. The intervention is informed by three theoretical frameworks. First, based on a model of successful aging over the lifespan (CitationBaltes and Baltes 1990; CitationBaltes 1997), the intervention offers patients ongoing coping and communication support to facilitate selective optimization with compensation that may effectively maintain and achieve evolving goals. Second, recognizing the importance of health information processing style in cancer communication (CitationMiller 1995; CitationMiller et al 2001), the intervention takes into account patients’ propensities to monitor and blunt against threatening health information. Third and last, understanding that most middle-aged and older patients have faced previous life stressors, the intervention assumes that most patients in these mature age groups will be responsive to a non-directive client-centered approach to intervening (CitationRogers 1951, Citation1967).

Aging and advanced cancer

The incidence of cancer is rising and occurs with greater frequency throughout the middle and later years (CitationYancik 1997; CitationACS 2006). It is the leading cause of death among women in their forties and fifties and the second leading cause of death for men in this age group (CitationMerrill and Verbrugge 1999). The prevalence of cancer is highest among adults over age 60 and has now replaced heart disease as the leading cause of death among older adults in their sixties and seventies (CitationExtermann 2002). Age is an important factor in communication and medical decision making in both hospital (CitationHamel et al 1999; CitationCoe and Miller 2000; CitationRose et al 2000, Citation2004) and community-based settings (CitationSiegler and Levine 2000; CitationBalducci and Beghe 2002). For patients with advanced cancer, decision making often occurs within “palliative care”. The objective of palliative care is to optimize quality of life and manage symptoms rather than to cure, but its treatments may range from invasive measures that can prolong life to measures assuring comfort, regardless of effect on life extension (CitationCleary and Carbone 1997; CitationEsper et al 1999).

The context of when in the life span a diagnosis of cancer occurs has major implications for patients in terms of distress, coping, and communication problems (CitationGanz et al 1985; CitationRose 1991, Citation1993; CitationFilipp 1992; CitationRose et al 2004). The potential need to facilitate and advocate for the expression of care needs and assure implementation of preferences has been shown differ for older cancer patients (CitationNussbaum et al 2003; CitationRose et al 2004). Many older adults look forward to continued years of independence, yet with advancing age the majority must cope with growing limitations in physical and cognitive functioning as well as the loss of loved ones. At the same time, older adults may be more reticent to become actively involved in medical treatment decision making (CitationHaug and Ory 1997; CitationAdelman et al 2000). Terminal cancer in middle-aged adults often brings other challenges for patients, especially as children approach adulthood and/or older parents require assistance. Such different circumstances have significant effects on coping and decision making for patients. Concerns about aging and the personal burden of treatment (CitationBalducci and Beghe 2002) as well as about the potential use of age as a criterion for medical decision making (CitationGinzberg 1990; CitationBinstock and Post 1991) further emphasize the importance of developing age-sensitive interventions that can maximize patient adaptation to both aging and cancerrelated losses.

The few studies that do compare middle-aged and older age groups find important differences in both medical and psychosocial domains (CitationProhaska et al 1985; CitationFilipp 1992; CitationRose 1993; CitationClark-Plaskie and Lachmann 1999). For example, in comparing hospitalized advanced cancer patients, differences were found between middle-aged and older patients’ preferences as well as end-of-life care practices and outcomes (CitationRose et al 2000, Citation2004). Indeed, comparisons between middle-aged and older advanced cancer patients can provide more precise information about potential unique problems and intervention effects in the earlier versus later stages of maturity. Thus, in assessing age differences in processes and outcomes of interventions, it is important to compare middle-aged patients in their forties and fifties (40–60) and young-old patients in their sixties and seventies (61–80). These two age groups, with slight variation in proposed age cut-points (eg, 60 vs 65), have been conceptualized as worthy of separate analysis in studies on adult development and health and disease in adulthood (CitationSilliman et al 1997; CitationMerluzzi and Nairn 1999; CitationMerrill and Verbrugge 1999; CitationStaudinger and Bluck 2001). In advanced cancer, the great majority (>90%) of patients seeking treatment in tertiary cancer care are between 40 and 80 years old (CitationRose et al 2004).

CitationBaltes and Baltes (1990) developed a theoretical model of successful aging that proffers selective optimization with compensation over the lifespan. According to this model, selection processes address the choice of goals, life domains, and life tasks whereas compensation and optimization are concerned with the means to maintain or enhance chosen goals overtime (CitationBaltes and Carstensen 1999, p 218). Optimization involves a narrowing of goals and expectations that build on remaining strengths and capacities for realistic achievement. Compensation often requires intervention, as a response to loss in capacity to meet goals, can be automatic or planned and might require new skills (CitationBaltes and Baltes 1990; CitationBaltes 1997). Similarly, in advanced cancer, coping and adaptation often necessitates clarifying and shifting life goals and goals of care while simultaneously modifying strategies for optimization with compensation from the early treatment phase through end of life. As the disease progresses, patients may seek support in (1) refocusing on personal goals that are most valued and achievable and (2) compensating through medical care and practical supportive services that maximize achievement of goals, including home care and hospice (CitationMor et al 1987, Citation1992). These adaptive processes and needs for support may differ for older patients (eg, CitationRose 1993; CitationMor et al 1994).

Psycho-oncology interventions for advanced cancer patients

During the past several decades, numerous psycho-oncology interventions to reduce cancer patients’ distress levels and improve coping skills have been tested (CitationRowland 1990; CitationFawzy et al 1995; CitationNezu et al 1998; CitationMeyer and Mark 1999). The majority of these interventions involve structured, time-limited support groups or educational programs for patients, particularly in the early diagnosis and treatment phase of the disease. Psycho-oncology interventions primarily focus on patients’ emotional and physical distress and coping abilities (CitationMassie et al 1990; CitationFawzy et al 1995; CitationLoscalzo and Brintzenhofeszoc 1998; CitationBaum and Andersen 2001; CitationBalducci and Beghe 2002). However an additional important goal for such interventions is to improve patients’ ability to understand symptoms and treatment decisions and communicate their ongoing needs and preferences for support and care to their physicians. This is especially important given that previous interventions to improve physician decision making practices and patient quality of life outcomes have had minimal effect (eg, CitationSupport Principal Investigators 1995). Indeed, numerous studies indicate that seriously ill patients and their physicians continue to have difficulty communicating about poor prognoses and end-of-life care (CitationMiyaji 1993,Citation1994; CitationWeeks et al 1998; CitationLynn et al 2000a, Citation2000b).

Lessons learned from the unsuccessful SUPPORT intervention, which involved nurse discussions with hospitalized patients and families about care decisions, have informed the development of more recent initiatives (CitationSUPPORT Principal Investigators 1995; CitationLynn et al 2000a). For example, CitationJoanne Lynn and her colleagues (2000b) made the following observations of factors that may have contributed to SUPPORT’s ineffectiveness: (1) patients’ preferences evolve as they confront new situations, and patients often find difficulty in fully articulating their wishes; (2) as the disease progresses, care situations are resolved in predictable ways and may go unmentioned as decision points; (3) patients and families often delay or dodge taking responsibility for making a choice, perhaps fearing uncertainty or subsequent regret; and (4) patients may behave in seemingly irrational ways, focusing on how they appear to loved ones, avoiding talk about death, and/or framing their experience in fatalistic or magical ways (p S215). Such behaviors have been well documented in cancer patients and are often described in terms of distress, coping and communication problems (CitationRoland 1990; CitationGrassi et al 1993; CitationDavidson et al 1999).

The dynamic nature of coping and communication in late stage cancer patients (CitationDavidson et al 1999; CitationNezu, Nezu, Houts, et al 1999; CitationFolkman and Greer 2000) argues for interventions that support patients across conditions and settings, over time, and through illness progression as life circumstances and perspectives about goals of care evolve. Telephone interventions have had promise in this regard and models have been tested (CitationBucher et al 1998), ranging from structured, fairly brief interventions (CitationAlter et al 1996; CitationNezu, Nezu, Friedman, et al 1999; CitationNezu, Nezu, Houts, et al 1999) to long term counseling interventions for early stage (CitationMarcus et al 1998) or high risk/metastatic breast cancer patients (CitationDonnelly et al 2000). Issues surrounding coping and communication behaviors are independent of late-stage cancer type. Thus, all patients with near end stage cancers may benefit from a coping and communication support intervention tailored to patient preferences.

Aging and psycho-oncology interventions

Psycho-oncology interventions appeal largely to patients who are middle-aged or younger adults (CitationMassie et al 1990; CitationMeyer and Mark 1999; CitationNezu, Nezu, Friedman, et al 1999). However, age is not specifically evaluated in most reviews of psycho-oncology interventions for adults (CitationMassie et al 1990; CitationFawzy et al 1995). The fact that older patients report lower levels of distress is often interpreted as their having less need or urgency for coping and communication support (CitationGrassi et al 1993; CitationNordin and Glimelius 1998; CitationSchnoll et al 1998). This may potentially mask the unique problems that older patients experience (CitationHarrison and Maguire 1995; CitationGanz 1997; CitationExtermann 2002). Interventions typically have not been designed to accommodate preferences for engagement of different age groups, especially older adults.

Review of psycho-oncology and coping literature suggests several components that are key for a coping and communication support intervention tailored to advanced cancer patients over time: (1) initial screening for level of distress and related problems, including communication difficulties; (2) an in-home face-to-face care conference with a trained practitioner to set the stage for addressing coping and communication concerns of patients and family caregivers; (3) ongoing follow-up contact with a trained practitioner to address new stressors as well as to reappraise continuing coping and communication problems; and (4) multiple means of immediate access to the practitioner including phone and e-mail communication and requests for web-search guidance. These components have been tested in previous intervention studies, although no single study represents the full combination in programs for middle-aged and older advanced cancer patients.

Based on research linking distress with poor coping, care decision making and quality-of-life outcomes, The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (CitationNCCN 1999) has recommended screening cancer patients of all ages for psychosocial distress and problems associated with distress (CitationZabora 1990). Anxiety and depression are associated with coping and communication problems, as well as with amplification of pain and other symptoms (CitationBlock 2000; CitationMcCarthy et al 2000). Anxiety in particular is linked to avoidance or blunting behaviors (CitationDunkel-Schetter et al 1992; CitationMiller 1995; CitationMiller et al 1996; CitationNordin and Glimelius, 1998) that can undermine contact and communication with physicians and/or family members. Indeed, middle-aged and older patients can be helped to understand the connection between their coping and communication behaviors (CitationOng et al 1999; CitationDowsett et al 2000) and this may be best accomplished using Miller’s guidelines for tailoring psychosocial interventions to the individual’s health information-processing style (CitationMiller et al 2001). With a better understanding of one’s own tendency to engage in monitoring and blunting behaviors in response to threatening health cues, patients may be helped to communicate more effectively with clinicians. Cancer patients’ communication preferences (CitationRose 1990, Citation1993) can be important considerations in coaching patients on how to better interact with clinicians, especially as life goals and care goals may shift (CitationButow et al 1994; CitationTennstedt 2000). Communication problems with physicians differ by age group and may be difficult to detect or accurately assess in elderly patients (CitationGanz 1997; CitationAdelman et al 2000; CitationNussbaum et al 2003).

Our coping and communication support intervention is tailored to the preferences of middle-aged and older advanced cancer patients and includes components suggested as essential by previous studies. It is based on three theoretical frameworks (see for our conceptual model). First, as in models of successful aging, coping and adaptation in advanced cancer involves a process of selecting and shifting personal life goals and goals of care while simultaneously developing strategies for optimization with compensation (ie, CitationBaltes and Baltes 1990; CitationBaltes 1997) from the early treatment phase through end of life. Second, communication in advanced cancer is affected by patients’ health information processing style (ie, monitoring and blunting; CitationMiller 1987, Citation1995) and understanding individual differences in attention to and avoidance of threatening health cues is key in developing strategies for more effective communication and decision making about goals over time. Third, the majority of middle-aged and older adults diagnosed with late-stage cancer have already adapted to a number of previous life changes and stresses. Consequently, patients in these mature age groups may be most responsive to a non-directive person-centered approach (CitationRogers 1951, Citation1967) in providing coping and communication support over time. It is anticipated that this tailored intervention may be associated with quality of care and quality of life in advanced cancer and with quality of care and quality of life outcomes at end of life.

CCS intervention design and methods

Components of the CCS intervention

This intervention is designed to be implemented with newly diagnosed late-stage cancer patients who are estimated to have a median life expectancy of one year or less. We enroll stage IV (or stage III lung or pancreatic) patients with the goal of establishing a supportive relationship and providing ongoing coping and communication support from the early treatment phase for late-stage cancer through end of life. The CCS intervention is being tested in a randomized controlled trial conducted in two ambulatory cancer clinics that provide care for the underserved patients are stratified by the two age groups and randomized to the intervention described in this paper or to a usual care control group. There are five components to this tailored CCS intervention for middle aged and older advanced cancer patients as outlined below.

Screening for distress and communication problems

Newly diagnosed late-stage cancer patients who enroll in the study are first screened by clinic-based research staff for distress (distress thermometer), anxiety, depression, and problems associated with distress, using the 1999 NCCC guidelines. Patients randomized to the intervention are then called by a randomly assigned coping and communication support practitioner (CCSP; see below for a description of CCSPs) to schedule an in-home care conference. In this call, patients are encouraged to choose a family member (the person upon whom they most depend for support and assistance in care decision making) to participate in the care conference.

Initial care conference

A key feature of this intervention is the initial care conference to establish a connection between the patient and family member/s and the CCSP to set the stage for telephone follow-up. Whenever possible, this initial care conference occurs in the patient’s home environment, thus allowing the CCSP to observe the relationship between patient and family and to assess the home and determine potential needs for practical assistance. During the conference, CCSPs review patient responses that were collected in the baseline interview about distress, including measures of anxiety and depression (POMS short form) (CitationSachman 1983) and health information processing style (Monitor-Blunter Style Scale – MBSS Short Form) (CitationSteptoe 1989). The MBSS assesses patients’ tendency to seek out information about threatening health cues (monitoring) and to seek distraction from threatening health cues (blunting) that can prompt discussion about (1) coping and communication issues, (2) strategies to address problems, and (3) concerns and expectations regarding illness and treatment. The CCSP also identifies patient preferences for their own engagement in the intervention (eg, type and frequency of contact) and how to include a family member in intervention follow-up. This is primarily a phone intervention available to patients 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. An initial schedule for follow-up phone contacts is set and amended by patients with each future contact.

During the initial care conference, the CCSP describes her goals for enhancing patient communication and shared decision making with healthcare team members, consulting about symptom management, and possibly facilitating patient contact with the physician, nurse/s, or social worker if needed. Patients are given a packet of information about the cancer clinic, potentially relevant community resources and how to contact CCSPs. To ensure that underserved patients have access to their CCSP, cell phones or a toll free phone number are provided for individuals who do not have home phones.

CCS follow-up phone contacts

Telephone interventions have been shown to be timely and efficacious for cancer patients (CitationAlter et al 1996; CitationBucher et al 1998; CitationMarcus et al 1998; CitationDonnelly et al 2000). In this study, the schedule for telephone contacts is flexible and tailored to patient preference. Telephone contacts offer opportunities to: (1) explore the physical, emotional, functional and social impact of advanced cancer and its treatment; (2) prepare patients psychologically for future therapy or progression of disease; (3) identify personal goals and goals of treatment; (4) identify further needs for information/support; (5) enhance expression of affect; (6) support hope and appropriate psychological defense; (7) foster independence; (8) facilitate coping; (9) optimize social support; (10) address practical problems; and (11) refer patients for symptom management, informational needs, and support.

All patients receive a follow up phone call from their CCSP within two weeks following the introductory care conference to check on patient understanding and preferences for engagement. Patients who initially score 4 or more on the distress thermometer are specifically encouraged to receive monthly phone contacts from their CCSP to monitor distress. If distress remains high or worsens after the first phone contact, or if the patient has significant emotional or psychiatric symptoms, the CCSP consults with the more highly trained intervention coordinator about additional evaluation and potential referral for psychiatric services. No prearranged schedule is proposed for low distress patients (scores less than 4 on the distress thermometer) unless requested. These patients are encouraged to contact their CCSP as desired. The CCS intervention continues until the patient dies. If the patient is referred to hospice at any time, the patient and caregiver decide whether to continue contact with the CCSP.

At each contact, the CCSPs review patient concerns and/or communication issues, identify symptoms, and provide consultation and referral for patients regarding symptom management. Patients and families are referred to their physician or appropriate care provider when symptoms are perceived to require health care provider intervention. Patients’ tendency to engage in monitoring and blunting in the context of threatening health cues is discussed with the patient to facilitate personal insight and develop strategies to address potential barriers in medical decision making (CitationMiller 1995; CitationMiller et al 2001). Discussions about patients’ preferences for intervention (eg, role-playing situations, facilitating/participating in discussion with members of the healthcare team) may occur as well.

CCS conjoint visit or health care team contacts

The CCSP’s role is to encourage direct communication between patient and physician. However, if patients are uncomfortable with this, the CCSP interacts with the physician and other members of the healthcare team in a facilitative role (with patient permission). The patient may request his/her CCSP to be present during a physician visit (conjoint visit) in the cancer clinic or to directly interact with the health care team. CCSP’s knowledge of patients’ information processing styles is helpful to promote effective communication between patients and healthcare providers. Suggestions made in earlier patient/health care contacts may be discussed and recommendations for supportive interventions (eg, nutrition, social work, home care) can be shared. In some instances, patients may prefer to meet face-to-face with their CCSP in the cancer clinic, while waiting for a scheduled appointment or treatment, although telephone calls are the primary mode of communication in the CCS intervention.

E-mail access and web-guidance

Patients with access to the internet may contact their CCSP by e-mail as well. E-mail/internet use in clinical practice is not without its challenges and we will explore its perceived usefulness and difficulties. Currently, older and underserved patients are less likely to use this mode of communication for information support (CitationDavison et al 2000; CitationSmyth et al 2007) and we expect this mode of contact to be fairly uncommon. In the introductory care conference, patients who have access to a computer and the internet are helped to determine how to utilize this aspect of the intervention eg, sending emails to CCSP and learning how to interpret or search for information on the web (CitationBucher and Houts 1999). Referrals for guided searches and perspectives on the accuracy of web-based information or recommendations are made to the American Cancer Society, the National Cancer Institute and reliable local sources.

Problem domains identified and addressed in the CCS intervention

Seven focal problem domains were identified from a review of the literature on coping and communication in advanced cancer. Specification of problem domains for interventions and quality improvement in palliative care is a useful example in this regard (CitationNCP 2001). Our goal in addressing the problem areas described below is to foster effective coping and communication in maintaining or shifting life goals and care goals according to patient needs and preferences. Middle-aged and older adult patients may experience problems in any of the seven domains, although the frequency or extent of these problems may differ by age group over time. (Intervention strategies used to address these problems areas are described in a subsequent section of this paper).

Psychological

Assessment of psychological distress and well being is based on the premise that every patient at every stage of the cancer continuum experiences some degree of psychological distress (CitationHolland 1999, Citation2000). It is estimated that approximately one-third of patients with cancer experience severe psychological distress (CitationDerogatis et al 1983; CitationZabora et al 2001), with the prevalence of anxiety and depression being as high as 70% in advanced cancer (CitationKaasa et al 1993).

Existential

A study of concerns of the terminally ill (CitationGreisinger et al 1997) found that coping with existential issues was the most important type of concern among more than 85% of patients with advanced cancer. Existential issues that threaten a person’s intactness are experienced as one confronts one’s mortality or the associated concerns regarding health, futility, meaningless, remorse, death related anxiety and disruption and engagement with and purpose in life (CitationKissane 2000). “Existential plight” is recognized as “a distinct phase of cancer to which almost all patients are subjected” (CitationWeisman and Worden 1976, p 3) and is also a developmental issue with aging as patients reflect on the course of their lives (CitationNussbaum et al 2003).

Communication with family and friends

This problem area encompasses the relationship between patients and families, communication problems, satisfaction with relationships, etc. Patients and families need to relate on unique levels as the disease progresses and their relationship and communication patterns change. Patients with advanced cancer frequently identify communication with family and friends as a prominent concern (CitationGreisinger et al 1997). This includes being able to express feelings, say goodbye, and know that family members will manage after death (CitationSpiroch et al 2000). Stress in the patient/family member dyad can worsen if patients give up decision-making, become incapable of understanding the ramifications of decisions or stop communicating their wishes. A “conspiracy of silence” can develop as patients and family members attempt to protect each other from difficult emotions or conflicts (CitationRose and Haug 1999; CitationZhang and Siminoff 2003a). Patient-family discord about treatment decisions can be influenced by differing perceptions of stress and symptoms or goals for cancer care (CitationZhang and Siminoff 2003b; CitationSiminoff, Rose, et al 2006). The CCS intervention can promote support and understanding between patients and family members in identifying symptoms, facilitating expression of feelings, and discussing patients’ wishes for treatment goals.

Communication with healthcare providers

Communication issues with healthcare providers in advanced cancer can affect informed decisions about end-of-life care. Research on patient-physician communication indicates that patients continue to have unmet communication needs. Serious gaps in recall and understanding that can occur during psychological and physical health crises and differences in communication styles of providers and their underserved or older patients can complicate decision making (CitationSiminoff, Graham, et al 2006). Indeed, the SUPPORT study (CitationSUPPORT Principal Investigators 1995) determined that physicians and other healthcare professionals had an inaccurate understanding of symptoms and end-of-life wishes of patients with advanced disease. Additionally, patient preferences and needs for information can differ widely (CitationClayton et al 2005). Interventions to facilitate such ongoing communication and decision making with health care providers should be available at times when the patient most needs assistance in understanding and clarifying personal goals and treatment goals and concerns over time through the shifts that may occur in palliative care.

Symptom management

Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that patients with advanced cancer (CitationWalsh et al 2000), report a high prevalence of symptoms related to treatment or disease. Symptom distress is the strongest predictor of overall quality of life in people with advanced cancer (CitationMcMillan and Small 2002). The amount or level of physical or mental upset, anguish, or suffering experienced by a person differs depending on specific symptoms. For instance, patients experiencing pain are twice as likely to develop psychiatric complications as patients without pain (CitationDerogatis et al 1983). As symptoms worsen with advanced disease, patients can benefit from opportunities to express concerns about specific symptoms and their management (CitationGreisinger et al 1997). CCSPs may be able to help patients advocate for themselves with their health care providers about urgent or emergent symptom distress to obtain appropriate treatment.

Practical concerns

The financial burden on cancer patients has grown considerably, with many expenses related to cancer care being hidden costs, including insurance premiums, deductibles, copayments, transportation, lost income, and miscellaneous expenses (CitationWagner and Lacey 2004). These expenses can promote a barrier to comprehensive cancer care. Factors related to being underserved also may pose challenges in cancer care, including inadequate educational attainment and low literacy (CitationNielsen-Bohlman et al 2004), unemployment, substandard housing, chronic malnutrition, limited access to health care, and risk promoting lifestyles, attitudes and behaviors. Practical issues and concrete service needs require serious attention in a coping and communication intervention for advanced cancer patients (CitationMor et al 1987, Citation1992) and these needs are expected to differ by age group (eg, CitationMor et al 1994).

Caregiver burden

Advanced cancer patients may become concerned about being a burden to others. Such concerns may be triggered by the apparent impact on the personal time, social roles, physical and emotional states, and financial resources of family caregivers (CitationGiven et al 2001). With increased illness, patients may become concerned about the amount of time and difficulty of caregiving tasks, such as administering medical/nursing treatments, providing emotional support, assisting with activities of daily living, and arranging for medical treatment and follow ups (CitationBakas et al 2004). The CCS intervention is designed to assess and address patients concerns about burden, using a number of interventions strategies described below.

Intervention strategies used in the CCS intervention

Coping and communication support is provided through a variety of intervention strategies. Based on a review of this literature (eg, CitationAndersen 1992; Meyer and Mark 1995) and applications to theoretical frameworks that inform our conceptual model (see ), we identified eight key strategies that may be used in the CCS intervention.

Supportive listening

As patients and caregivers experience treatments and symptoms associated with cancer, fears and psychological responses are common but can be difficult to express. The therapeutic value of expression of affect is demonstrated to be a mediating factor in the stress associated with cancer. Efforts to suppress sadness and other difficult emotions have been reported to increase dysphoric mood (CitationClassen et al 1996) and are associated with poorer coping (CitationKoopman et al 1998; CitationDerogatis et al 1979). Supportive listening can facilitate facing life threatening issues directly and help patients shift from emotion-focused to problem-focused coping (CitationMoos and Schaefer 1987) and can limit feelings of social isolation (CitationSpiegel and Diamond 2001). Facilitating emotional expression modulates distress and prepares the individual to cope with current and future stressors.

Education/handouts

The value of knowledge in adjustment to illness is well established. Patients with advanced cancer have many questions about disease course, prognosis and treatments. An essential element of effective cancer treatment includes knowledge acquisition. Psycho educational interventions including discussing concerns, giving and receiving information, problem solving, coping skills training, facilitating expression of emotion and social support have been found to reduce depressive symptoms in patients with cancer (CitationBarsevick et al 2002) and are beneficial to cancer patients in relation to pain (CitationDevine 2003), and nausea and vomiting (CitationDevine and Westlake 1995). In the CCS intervention, examples of educational topics include information and guidance about health system entry, cancer staging, helping patients understand when goals of care shift and whether decisions may be required, symptom management, utilizing information in approved sites, cancer therapy, and coping.

Cognitive/problem-solving

Cognitive behavioral approaches have empirical value in reducing and managing psychological distress in patients with cancer (CitationManne and Andrykowski 2006). For the purpose of the CCS intervention, cognitive therapy and problem solving will be separated from the behavioral interventions. This approach is based on the cognitive model, that the way situations are perceived influences emotions and includes problem solving and exploring automatic thoughts and coaching. Effective problem solving has been shown to reduce depression (CitationHuibers et al 2003) and improve quality of life of cancer patients in preliminary findings (CitationNezu et al 1998). Exploring problems and coaching patients on effective identification and communication of the needs and goals of themselves, their families, friends and healthcare providers is key in this intervention.

Validation

The role of a helper in client-centered therapy is to assume the internal frame of reference of the client, to perceive the world as the client sees it, to perceive the client himself as he is seen by himself, and to communicate something of this empathic understanding to the client (CitationRogers 1951, p 29). The central hypothesis of this approach is that the individual has within him/herself vast resources for self understanding, for altering his/her self concept, attitudes, and self-directed behavior--and that these resources can be tapped if only a definable climate of facilitative psychological attitudes can be provided. Training in client-centered empathic communication includes nonverbal and verbal behaviors such as reflection, validation, support, partnership, and respect. Validation of the individual’s position is perceived as accepting and is a useful intervention demonstrated by using statements expressing acceptance of the individual’s views, or legitimizing a concern. The validation of patient concerns is useful as a technique to promote safety (CitationEllingson and Buzzanell 1999) and quality care for depressed patients.

Case navigation

It is important to clarify the meaning of case navigation as one strategy used in the CCS intervention, given the rapid growth in clinical use of “navigators” to improve cancer care (CitationDignan et al 2005; CitationDohan and Schrag 2005; CitationFreeman 2006; CitationRayford 2006). The role of the navigator has been focused mostly on maximizing adherence to clinically accepted cancer screening and treatment protocols and minimizing perceived barriers to care (CitationSchrag 2005). Alternatively, CCSPs take direction from the patient without access to medical information or formal connection to the clinic or physician group. In the CCS intervention, case navigation may involve coordinating transportation, providing outreach and education, arranging clinic appointments, facilitating reimbursement for services, bridging cultural and language differences between providers and patients, and providing emotional and social support according to patient preference. CitationMor and colleagues (1992) found with advanced cancer that older age and low income predicted a need for help with personal care and transportation. This intervention was designed to reduce the prevalence of unmet needs by helping patients access important services and resources within the healthcare system and in the community.

Behavioral

Behavioral strategies in providing coping and communication support span guided imagery, relaxation training, music, distraction, role playing, and other broadly accepted complementary therapies involving behavioral change by the patient. The use of such behavioral interventions during cancer treatment has shown positive benefits in reducing anticipatory nausea, pain, and distress (CitationLuebbert et al 2001; CitationRedd et al 2001; CitationMiller and Kearney 2004). Although complementary therapies have been less frequently pursued by the current cohort of older adults (CitationRose et al 1998), the potential benefit of such therapies in palliation could be similar for patients in this age group. Middle-aged and older patients will be informed of appropriate strategies and may be coached in behavioral interventions in facilitating coping.

Web-based guidance

Computer-based programs have been tested with underserved women with breast cancer and have shown value in improving competence in seeking information, participating in care, communicating with physicians, and obtaining social support (CitationGustafson et al 2001). Computer based nursing interventions providing information on symptoms and symptom management, emotional support and counseling for patients with newly diagnosed cancer and families has been shown to be effective in reducing depression and improving other measures of psychological health (CitationRawl et al 2002). Computer mediated communication systems have been utilized for support groups to reduce or eliminate the barriers to face-to-face support. Patients may need ongoing guidance in seeking or interpreting information and its credibility in the media and on the internet.

Referral

The CCS intervention is designed to supplement usual care in the oncology care setting. In the development of the NCCN Distress Management Guidelines (CitationNCCN 2006), it was recognized that 1/3 of cancer patients in the outpatient setting experienced significant distress and an even larger proportion of those with poorer prognosis experienced distress (CitationZabora et al 2001). A distress rating of 4 or greater results in referral to trained staff who explore the source of distress in more depth (CitationNCCN 2006). Although this intervention may effectively address normal fears, worries, communication concerns, and practical needs, referral is a critical part of comprehensive care. Indeed, an important goal of this intervention is to help patients best communicate their needs and wishes to the staff involved in their care.

Coping and communication support practitioners (CCSP)

The role of the CCSP was developed to assist patients with advanced cancer to understand their options for treatment, communicate their needs regarding treatment and end-of-life decisions effectively, ensure resolution of practical issues through services/referrals, navigate the healthcare system for pain and symptom management and learn ways of coping with emotional and existential issues that often accompany the diagnosis and management of cancer and terminal illness. CCSPs are advanced practice nurses with either a master’s degree in psychiatric/mental health or with other mental health training. Recruits to this position are screened for their experience with aging, cancer, and mental health; level of knowledge about coping and communication; commitment to the communication skills needed for this study; ability to accommodate to flexible hours; and comfort with allowing the client to ultimately control or chart their own course.

Given that CCSPs provide telephone access on a 24/7 schedule, it has been determined that a reasonable full-time caseload is 80-100 clients, including patients and their family caregivers. By design, CCSPs rely on patients’ perspectives and preferences; they do not have access to patient medical records. Challenges faced by CCSPs include not having access to records, 24/7 scheduling, the unpredictability of crises which may occur in multiplicity, and the unpredictable requests of high user clients who require frequent and lengthy contacts. In addition, working between the terminally ill who may present with poor resources and an overburdened health care system can be a significant stressor. Several techniques are utilized to mediate the workload stress. One is the weekly team care conferences where attendees provide expertise in medicine, geriatrics, palliative care and clinical ethics and in discussions of ethical concerns and difficult situations for problem-solving and support. The second is frequent opportunities to memorialize the deaths of patients and to recognize the impact of these deaths on the CCSP and team. In addition, the CCSPs keep weekly logs of their insights, most difficult challenges, and ideas about rapport-building with patients which are discussed with the CCS Intervention Coordinator for further exploration when needed.

CCSP training begins with an orientation to the three theoretical frameworks illustrated in . They are instructed in applying the theory of successful aging as “selective optimization with compensation” to foster effective coping and adaptation among recently diagnosed late-stage cancer patients through end of life. Special attention is given to theory and research on patient-doctor communication and decision making processes in cancer during the active treatment phase and at end of life. The CCSPs are taught the importance of health information processing styles and how to take into account patient scores on monitoring and blunting when coaching patients. They are informed in the use of Rogerian Client-Centered (Person-Centered) approach to establish therapeutic rapport with the patient. In that light, the goal of all interactions is a nondirective style toward facilitation of self-actualization, self-realization and helping the client to explore barriers to expressing goals for therapy and make appropriate decisions for treatment. As many patients express practical concerns, the CCSP is trained to help explore problems or may be asked to make calls and obtain services. In addition, the CCSP must provide brief therapies that foster relaxation, problem-solving, and coaching.

The CCSPs provide an important adjunctive role to the healthcare team in coaching, promoting and educating patients on new skills in communication, and assisting patients to optimize participation in their own health care experience. This role changes over time as the illness of the patient progresses, treatment fails, or as realization of possible death occurs. A detailed description of CCSP roles and responsibilities, training and methods to ensure fidelity of the CCS intervention are described by CitationRadziewicz and colleagues (2007).

A critical responsibility of CCSPs is to document patient preferences, problem domains, intervention strategies and engagement in the CCS intervention. These data are essential to answer important questions about similarities and differences between middle-aged patients, in their 40s and 50s, and young-old advanced cancer patients, in their 60s and 70s, who constitute the great majority of patients treated in tertiary care ambulatory cancer clinics. It is important to note that less than five percent of patients enrolled in this study are over age 80 and, although these patients are also randomized to the intervention, this old-old age group (eg, CitationRose et al 2004) will be separately analyzed at the end of the study period.

The CCSPs document patient engagement in the intervention from the initial care conference to patients’ death. A password protected web-accessible database was specifically designed to document each contact with the patient. For the initial care conference, data are entered about the context (setting and length), problem domains identified and patient preferences for engagement, including frequency, mode (phone, cancer clinic, email) and directionality (initiation by CCSP, patient or family) of follow up contact. Similarly, for every follow up contact, data are entered about mode and directionality of communication, problem domains raised, intervention strategies used and any changes in preference for contact. Patient engagement in the intervention over time is examined to determine the frequency and length of contacts as well as in the problem domains raised and types of intervention strategies used after the initial care conference. In this paper, we report data on middle-aged (ages 40–60; N = 82) and young-old (ages 61–80; N = 79) patients who were enrolled and randomized to the intervention, who participated in an initial care conference and had access to the intervention for a minimum of six weeks after the initial care conference. These data represent patterns of engagement for patients enrolled during the first half of a four-year recruitment period in the CCS intervention study.

Patient engagement in the CCS intervention

Profile of middle-aged and young-old advanced cancer patients

Demographic characteristics

Advanced cancer patients in the two age groups were not significantly different on the majority of demographic characteristics (see ). The majority of patients enrolled in the two cancer clinics and randomized to the CCS intervention were male, had annual incomes below $20,000, and had a high school education. Middle-aged patients were more likely than older patients to be unmarried, uninsured or on Medicaid only, indicating that this population may be especially vulnerable in coping with the diagnosis and treatment of late-stage cancer.

Table 1 Advanced cancer patients’ demographic characteristics at intake

Physical and psychosocial status

Patients’ physical status, psychosocial status and health information processing style were assessed at baseline. includes a brief profile of patient characteristics in these areas by patient age group. Physical status was assessed in a count of comorbidities documented in chart reviews and standardized measures of physical symptom distress and functional limitations. The 13-item symptom distress scale (CitationMcCorkle and Young, 1978) was administered during the initial screen for distress and limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) (CitationKatz et al 1963) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (CitationFillenbaum 1988) were measured in baseline interviews. Psychosocial status was measured on the distress thermometer (CitationNCCN 1999) and on anxiety and depression subscales of the Profile of Mood Scale (POMS, Short Form) (CitationSachman 1983) administered during the initial screen for distress. Health Information Processing Style was assessed with the Miller Monitoring and Blunting Scale-Abbreviated Version (CitationMiller 1987; CitationSteptoe 1989) in baseline interviews with patients.

Table 2 Advanced cancer patients’ physical and psychosocial characteristics

As shown in , there were significant differences between middle-aged and young-old advanced cancer patients in co-morbid conditions, symptom distress, and psychosocial status but not in functional status or health information processing style. Whereas young-old patients had more documented co-morbidities, middle-aged patients reported more physical symptoms and emotional distress and experienced higher levels of anxiety and depression than the older patients. In terms of health information processing style, patients in both age groups had higher scores in monitoring than in blunting.

Patient preferences and engagement in the CCS intervention

Preliminary findings on the initial care conference

The context of patients’ initial care conference was similar for the two age groups, including the agreed upon setting and actual length of these meetings (see ). Although there were no significant differences in these variables, it is important to note a tendency for more middle aged patients to prefer meeting in the cancer clinic versus their own home. These initial care conferences lasted approximately an hour and a half for patients in both age groups. On average, patients in both age groups were first seen within their fourth month following a diagnosis of late-stage cancer and virtually all patients identified one or more problems during the initial care conference (see ). Symptom management and psychological and practical aspects of coping were the most prevalent problems raised by both age groups. More middle aged than young-old patients raised problems in communicating with family/friends about their disease and/or treatment decision making. The great majority of patients preferred that the CCSP take the initiative in follow up contacts, primarily by phone and on a weekly to monthly basis.

Table 3 Context of initial care conference

Table 4 Advanced cancer patients’ problems and preferences in initial care conference

Preliminary findings on engagement in the intervention, problems identified and strategies used in the first six weeks following the initial care conference

There was a non-significant trend of middle-aged patients engaging in more follow-up contacts and of greater variability in their engagement. The majority of patients in both age groups had at least three follow up contacts with CCSPs within the first six weeks after the initial care conference. The majority of patients had weekly to monthly contacts and over 90 percent of these contacts occurred by phone with the great majority initiated by the CCSP, as originally preferred by patients (see ).

Table 5 Characteristics of patient contacts in first six weeks after initial care conference

As indicated in , the pattern of problems most frequently raised during follow up contacts was similar to the initial care conference, with symptom, practical, and psychological problems being most common. However, there were more age group differences in problem domains raised during follow up contacts, with more middle-aged patients raising practical and existential concerns in addition to problems communicating with family/friends about their disease or treatment goals. In both age groups, symptoms were raised in approximately 80% of follow up contacts. There were no apparent age-group differences in the intervention strategies used during follow up contacts. In both age groups the three most commonly used strategies in the early weeks of follow up contact were supportive listening, education/handouts and cognitive problem solving.

Table 6 Problem domains raised and intervention strategies used in first six weeks after initial care conference

Discussion of findings on patient engagement in the CCS intervention

This paper has described the CCS intervention and reported preliminary findings on the similarities and differences between middle-aged and young-old patients’ patterns of initial engagement in the intervention. As anticipated, the demographic profile of advanced cancer patients in this intervention was representative of populations treated in ambulatory cancer clinics that provide care for the underserved. The majority of patients in both age groups reported annual incomes below $20,000 and typically had a high school education. Because one of the two ambulatory cancer clinics in this study was in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center, it is not surprising that the majority of patients in both age groups were male. The finding that approximately 40% of patients were African American was expected, given that African Americans are the largest underserved minority group in the region. Middle-aged patients were especially vulnerable, given that more of these patients were unmarried and without medical insurance.

Consistent with findings in previous studies of advanced cancer patients, middle-aged patients reported higher levels of physical and emotional distress than older patients, including greater depression and anxiety. In contrast, as expected, older patients had more documented co-morbidities, averaging two conditions in addition to their cancer. The finding that most advanced cancer patients in both age groups were not experiencing significant functional limitation is consistent with previous literature, and may in part be explained by the fact that patients were only recently diagnosed and that older patients were young-old versus old-old. There was no age group difference in patients’ health information processing style, considered to be a stable characteristic of individuals. The finding that patients in both age groups had higher scores in monitoring than in blunting style will require further analyses to understand its meaning and implications. Given past and present data on older patients’ lower distress ratings and their relatively low rates of participation in previous psycho-oncology programs, an important question here was whether older patients would need or chose to engage in CCS intervention and in what ways.

Patients randomized to the CCS intervention were contacted by a CCSP by phone to arrange the initial face-to-face care conference, preferably in the patient’s home. Although there were no significant age group differences in the agreed upon setting, it appears that older patients may be more willing to allow a home visit. On average, these initial care conferences take about an hour and a half to establish rapport and assess the patient’s overall situation, including initial coping and communication problems and preferences for follow-up contact. Although our ultimate goal is to implement this type of intervention as soon as possible after a diagnosis is made, the lag time from diagnosis to the initial care conference associated with this being a randomized clinical trial was longer than would be expected if implemented as usual care in cancer clinics. The majority of patients enrolled were receiving at least one form of active treatment (ie, chemotherapy, radiation or surgery).

In the initial care conference, virtually all middle-aged and young-old patients raised at least one problem area of concern, primarily related to symptoms, psychological or practical issues. At the outset, middle-aged patients reported more problems in communicating with family and friends about their cancer or treatment decisions. Neither age group expressed concerns about being a burden to family, at least during this early treatment phase. Although older patients had reported less physical and psychosocial distress at intake, their preferences for engagement in the intervention were very similar to those of middle-aged patients. Indeed, the great majority of patients in both age groups preferred to have contact on a weekly to monthly basis, conducted primarily by phone, with the CCSP initiating contact. This is the first study to document older cancer patients’ initial preferences for a tailored coping and communication support intervention. As it turns out, their preferences are similar to those of middle-aged advanced cancer patients.

Patterns of actual engagement during the first six weeks following the care conference were consistent with initial preferences and did not differ by age group. On average, patients had three to four contacts lasting approximately 10 minutes each and most of these were phone calls initiated by the CCSP. Although generally in keeping with initial preferences for weekly to monthly contact, patients’ original preferences appear to represent a slight overestimation of contacts sought during subsequent weeks. As in the initial care conference, the most common problem domains raised by patients in follow up contacts were related to symptoms, practical and psychological issues. The finding that more middle-aged than young-old patients raised practical or existential concerns and problems in communicating with family and friends provides important insight into the potential unique challenges faced by patients in this age group. Regardless of these age group differences in the prevalence of certain problem domains, the CCSPs used similar intervention strategies with the two groups.

The common use of supportive listening underlines the goals of this non-directive CCS intervention tailored to the ongoing needs and preferences of patients. Cognitive/problem-solving and educational support strategies also were used with the majority of patients in both age groups. Although validation was not originally conceptualized as a distinct intervention strategy, it has proven to be an important one in more recent documentation with approximately half of the patients in this sample. Attention to behavioral strategies, including the use of complementary therapies was reported only for 14% of middle-aged and 8% of older patients during this early treatment phase. Finally, although 17% of middle-aged and 22% of young-old patients reported having some form of access to the internet, these patients did not engage by email and CCSPs did not report providing web guidance to such patients in either age group during the initial six weeks of contact.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this CCS intervention is the first psycho-oncology intervention specifically designed to be age sensitive and to examine age-group differences in engagement from the early treatment phase for late-stage cancer through end of life. The intervention was designed to facilitate older patients’ access to and engagement in the intervention based on their own preferences for coping and communication support over time. With this in mind, the development of this intervention was informed by theory and research on successful aging (CitationBaltes and Baltes 1990; CitationBaltes 1997), health information processing style (CitationMiller1995; CitationMiller et al 2001) and non-directive client-centered therapy (CitationRogers 1951, Citation1961, Citation1967). Preliminary data on middle-aged and older patients indicate that older patients raise similar problems and voice similar preferences for engagement in the intervention, regardless of the fact that their baseline physical and emotional distress levels were lower. Older patients also did not differ from middle-aged patients in their level of engagement, key problems faced and intervention strategies used during the first six weeks of follow up contact. However, the finding that more middle-aged than young-old patients raised problems in communicating with family and friends and practical and existential concerns as well in follow up contacts provides important insight into the potentially unique coping and communication challenges faced by patients in the two age groups.

This intervention study will continue to enroll patients for another full year and will test hypotheses about age group differences in quality of care and quality of life outcomes for patients in the CCS intervention versus usual care control arms, from the early treatment phase after a diagnosis of advanced cancer through end of life. It is anticipated that this project will contribute to knowledge about processes and outcomes of the intervention for middle-aged and young-old advanced cancer patients who constitute the great majority of advanced cancer patients diagnosed and treated in ambulatory cancer clinics that provide care to the underserved. This age-sensitive and tailored intervention is expected to affect quality of care and quality of life outcomes for patients over time. Research findings will guide plans to modify and disseminate this intervention.

Acknowledgements

Funding sources National Cancer Institute: R01-CA10282, VHA HSR&D Merit: IIR-03-255, American Cancer Society: ROG-04-090-01. We wish to acknowledge our intervention staff (Rose Anne Berila and Amy Spuckler) and research staff (Mary Ellen Lawless, Anthony D’Eramo, Mary Hutchinson, Nasim Seifi) on this Project.

References

- American Cancer Society, [ACS]Facts and figures2006Atlanta, GAAmerican Cancer Society

- AdelmanRDGreeneMGOryMGCommunication between older patients and their physiciansClin Geriatr Med20001612410723614

- AlterCLFleishmanSBKornblithABSupportive telephone intervention for patients receiving chemotherapy – a pilot studyPsychosomatics199637425318824121

- AndersenBLPsychological interventions for cancer patients to enhance the quality of lifeJ Consult Clin Psychol199260552681506503

- BakasRAustinJKJessupSLTime and difficulty of tasks provided by family caregivers of stroke survivorsJ Neurosci Nurs2004369510615115364

- BalducciLBegheCManagement of cancer in the older personClin Geriatr2002105460

- BaltesPBOn the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: Selection, optimization and compensation as foundation of developmental theoryAm Psychol199752366809109347

- BaltesPBBaltesMMSuccessful aging: perspectives from the behavioral sciences1990New YorkCambridge University Press

- BaltesMMCarstensenLLBengstonVLSchaieKWSocial-psychological theories and their applications to aging: From individual to collectiveHandbook of theories of aging1999NYSpringer Publishing299226

- BarsevickAMSweeneyCHaneyEA systematic qualitative analysis of psychoeducational interventions for depression in patients with cancerOncol Nurs Forum200229738411817494

- BaumAAndersenBLBaumAAndersonBLPsychosocial intervention and cancerPsychosocial interventions for cancer2001Washington DCAmerican Psychological Association312

- BinstockRHPostSGBinstockRHPostSGOld age and the rationing of health careToo old for health care?1991BaltimoreJohns Hopkins University Press112

- BlockSDAssessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient ACP-ASIM end-of-life care consensus panelAnn Intern Med20001322091810651602

- BucherJAHoutsPSProblem-solving through electronic bulletin boardsJ Psychosoc Oncol1999168591

- BucherJAHoutsPSGlajchenMHollandJCTelephone counselingPsycho-oncology1998New YorkOxford University Press75866

- ButowPNDunnSMTattersallMHNPatient participation in the cancer consultation: evaluation of a question prompt sheetAnn Oncol199451999204

- Clark-PlaskieMLachmanMEWillisSLReidJDThe sense of control in midlifeLife in the middle psychological and social development in middle age1999San DiegoAcademic Press181208

- ClassenCKoopmanCAngellKCoping styles associated with psychological adjustment to advanced breast cancerHealth Psychol19961543478973923

- ClaytonJMButowPNTattersallMHNThe needs of terminally ill cancer patients versus those of caregivers for information regarding prognosis and end-of-life issuesCancer20051039571964

- ClearyJFCarbonePPPalliative medicine in the elderlyCancer1997801335479317188

- CoeRMMillerDKCommunication between the hospitalized older patient and physicianClin Geriatr Med2000161091810723622

- DavisonKPPennebakerJWDickersonSSWho talks? The social psychology of illness support groupsAm Psychol2000552051710717968

- DavidsonJRBrundageMDFeldman-StewartDLung cancer treatment decisions: Patients’ desires for participation and informationPsychooncology199985112010607984

- DerogatisLRMorrowGRFettingJThe prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patientsJAMA198324975176823028

- DerogatisLRAbeloffMDMelisartosNPsychological coping mechanisms and survival time in metastatic breast cancerJAMA197924215048470087

- DevineECA meta-analysis of the effect of psychoeducational interventions in pain on adults with cancerOncol Nurs Forum200330758912515986

- DevineECWestlakeSKThe effects of psychoeducational care provided to adults with cancer: Meta-analysis of 116 studiesOncol Nurs Forum1995221369818539178

- DignanMBBurhansstipanovLHaritonJCancer control200512Suppl 2283316327748

- Distress Treatment Guidelines for Patients, Version 1. 2005, National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Cancer Society

- DohanDSchragDUsing navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approachesCancer20051048485516010658

- DonnellyJMKornblithABFleishmanSA pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy by telephone with cancer patients and their partnersPsychooncology20009445610668059

- DowsettSMSaulJLButowPNCommunication styles in the cancer consultation: Preferences for a patient-centered approachPsychooncology200091475610767752

- Dunkel-SchetterCFeinsteinLGTaylorSEPatterns of coping with cancerHealth Psychol19921179871582383

- EllingsonLLBuzzanellPMListening to women’s narratives of breast cancer treatment: a feminist approach to patient satisfaction with physician-patient communicationHealth Commun1999111538316370974

- EsperPHamptonJNFinnJA new concept in cancer care. The supportive care programAm J Hosp Palliat Care1999167132211094908

- ExtermannACancer in the older patient: a geriatric approachAnn of Long-Term Care2002104954

- FawzyFIFawzyNWArndtLACritical review of psychosocial interventions in agingArch of Gen Psychiatry199552100137848046

- FilippS-HMontadaLFilippS-HLernerMJCould it be worse? The diagnosis of cancer as a prototype of traumatic life eventsLife crises and experiences of loss in adulthood1992Hillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers2356

- FillenbaumGGMultidimentional functional assessment of older adults1988Hillsdale, NJErlbaum

- FolkmanSGreerSPromoting psychological well-being in the face of serious illness: When theory, research and practice inform each otherPsychooncoloogy200091119

- FreemanHPPatient navigation: a community centered approach to reducing cancer mortalityJ Cancer Edu200621S1114

- GanzPAInteraction between the physician and the older patientThe oncologist’s perspectiveCancer199780127029317179

- GanzPASchagCCHeinrichRLThe psychosocial impact of cancer on the elderly: A comparison with younger patientsJ Am Geriatr Soc198533429353998352

- GinzbergEHigh-tech medicine and rising health care costsJAMA1990263182022107340

- GivenBKozachikSCollinsCMaasMBuckwalterKHardyMCaregiver role strainNursing care of older adult diagnoses: outcome and interventions2001St. Louis, MOMosby67995

- GrassiLRostiGLasalviaAPsychosocial variables associated with mental adjustment to cancerPsychooncology199321120

- GreisingerALorimorRAdayLTerminal ill cancer patients. Their most important concernsCancer Pract19975147549171550

- GustafsonDHHawkinsRPingreeSEffect of computer support on younger women with breast cancerJ Gen Intern Med2001164354511520380

- HamelMETenoJMGoldmanLPatient age and decisions to withhold life-sustaining treatments for seriously ill, hospitalized adultsAnn Intern Med19991301162510068357

- HarrisonJMaguirePInfluence of age on psychological adjustment to cancerJ Psychosoc Oncol19954338

- HaugMOryMIssues in elderly patient-provider interactionsResearch on Aging199793443589142

- HollandJCNCCN practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distressOncology1999131134710370925

- HollandJCPerryMCAn algorithm for rapid assessment and referral of distressed patientsAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book2000Alexandria, VAAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology12938

- HuibersMJBeurskensAJBleijenbergGThe effectiveness of psychosocial interventions delivered by general practitionersThe Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online)2003(2)CD003494

- KaasaSMaltUHagenSPsychological distress in cancer patients with advanced diseaseRadiother Oncol19932719377692472

- KatzSFordABMoskowitzRWStudies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychological functionJAMA19631859141914044222

- KissaneDWPsychospiritual and existential distress: the challenge for palliative careAust Fam Physician2000291022511127057

- KoopmanCHermansonKDiamondSSocial support, life stress, pain and emotional adjustment to advanced breast cancerPsychooncology19987101119589508

- LoscalzoMBrintzenhofeszocKHollandJCBrief crisis counselingPsycho-oncology1998New YorkOxford University Press66275

- LuebbertKDahmeBHasenbringMThe effectiveness of relaxation training in reducing treatment-related symptoms and improving emotional adjustment in acute non-surgical cancer treatment: a meta-analytical reviewPsychooncology20011049050211747061

- LynnJArkesHRStevensMRethinking fundamental assumptions: SUPPORT’s implications for future reformJ Am Geriatr Soc200048S2142110809478

- LynnJDeVriesKOArkesHRIneffectiveness of the SUPPORT intervention: review of explanationsJ Am Geriatr Soc200048S2061310809477

- ManneSLAndrykowskiMAAre psychological interventions effective and accepted by cancer patients?II Using empirically supported therapy guidelines to decideAnn Behav Med2006329810316972804

- MarcusACGarrettKMCellaDTelephone counseling of breast cancer patients after treatment: A description of a randomized clinical trialPsychooncology19987470829885088

- MassieMJHollandJCStrakerNHollandJCRowlandJRPsychotherapeutic InterventionsHandbook of psycho-oncology: psychological care of the patient with cancer1990New YorkOxford University Press45569

- McCarthyEPPhillipsRSZhongZDying with cancer: patients’ function, symptoms, and care preferences as death approachesJ Am Geriatr Soc200048S1102110809464

- McCorkleRYoungKDevelopment of a symptom distress scaleCancer Nurs1978103738250445

- McMillanSCSmallBJSymptom distress and quality of life in patients with cancer newly admitted to hospice home careOncol Nurs Forum2002291421812432413

- MerluzziTVNairnRCAdulthood and aging: transitions in health and health cognitionLife-span perspectives on health and illness1999Mahwah, NJLawrence Erlbaum Assoc. Inc., Publishers189206

- MerrillSSVerbruggeLMWillisSLReidJDHealth and disease in midlifeLife in the middle1999San DiegoAcademic Press77103

- MeyerTJMarkMMSuinnRMVandenBosGREffects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized experimentsCancer patients and their families1999Washington DCAmerican Psychological Association16377

- MillerMKearneyNChemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting-Past reflections, present practice and future managementEur J Cancer Care2004137181

- MillerSMMonitoring and blunting: validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threatJ Pers Soc Psychol198752345533559895

- MillerSMMonitoring versus blunting styles of coping with cancer influence the information patients want and need about their diseaseCancer199576167778625088

- MillerSMRodoletzMSchroederCMApplications of the monitoring process model to coping with severe long-term medical threatsHealth Psychol199615216258698036

- MillerSMFangCYDiefenbachMABaumAAndersonBLTailoring psychosocial interventions to the individual’s health information processing style: the influence of monitoring versus blunting in cancer risk and diseasePsychosocial interventions for cancer2001Washington, DCAmerican Psychological Association34362

- MiyajiNTThe power of compassion: truth-telling among American doctors in the care of dying patientsSoc Sci Med199336249648426968

- MiyajiNTInformed consent, cancer, and truth in prognosis (letter)N Engl J Med19943318108065418

- MoosRHSchaeferJAMoosRHThe crisis of physical illness: an overview and conceptual approachCoping with physical illness: Vol. 2. New Perspectives1987New YorkPlenum325

- MorVAllenSMSiegelKDeterminants of need and unmet need among cancer patients residing at homeHealth Services Research199227337601500290

- MorVAllenSMalinMThe psychosocial impact of cancer on older versus younger patients and their familiesCancer1994747 Suppl2118278087779

- MorVGuadagnoliEWoolMAn examination of concrete service needs of advanced cancer patientsJ Psychosoc Oncol19875117

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network, [NCCN]Practice guidelines for the management of psychosocial distressOncology1999131134710370925

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network, [NCCN]NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology™: distress management, version 120068

- [NCP] National Concensus ProjectClinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP)2001 [online]. Accessed January 17, 2007. URL: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org

- NezuAMNezuCFriedmanSHelping cancer patients cope: a problem-solving approach1998Washington, DCAmerican Psychological Association

- NezuAMNezuCMHoutsPSRelevance of problem-solving therapy to psychosocial oncologyJ Psychosoc Oncol199916526

- NezuCMNezuAMFriedmanSHCancer and psychological distress: Two investigations regarding the role of social problem-solvingJ Psychosoc Oncol1999162741

- Nielsen-BohlmanLHealth literacy: a prescription to end confusion2004Washington DCThe National Academies Press, Institute of Medicine

- NordinKGlimeliusBReactions to gastrointestinal cancer – variation in mental adjustment and emotional well-being over time in patients with different prognosesPsychooncology19987413239809332

- NussbaumJFBaringerDKundratAHealth, communication and aging: cancer and older adultsHealth Communication20031518794

- OngLMLVisserMRMVan ZuurenFJCancer patients’ coping styles and doctor-patient communicationPsychooncology199981556610335559

- ProhaskaTRLeventhalEALeventhalHHealth practices and illness cognition in young, middle aged, and elderly adultsJ Gerontol198540569784031405

- RadziewiczRRoseJHO’TooleEAssessing treatment fidelity in a “navigator” coping and communication support intervention for advanced cancer patientsPsychooncology20071653

- RawlSMGivenBAGivenCWIntervention to improve psychological functioning for newly diagnosed patients with cancerOncol Nurs Forum2002299677512096294

- RayfordWManaging the low-socioeconomic-status prostate cancer patientJ Natl Med Assoc2006985213016623064

- ReddWHMontgomeryGHDuHamelKNBehavioral intervention for cancer treatmentJ Natl Cancer Inst20019381023 Accessed January 29, 2007. URL: http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/93/11/81011390531

- RogersCRClient-centered therapy1951LondonConstable and Robinson LTD

- RogersCROn becoming a person1961BostonHoughton Mifflin

- RogersCRThe therapeutic relationship and its impact1967MadisonUniversity of Wisconsin Press

- RoseJHSocial support and cancer: Adult patients’ desire for support from family, friends, and health professionalsAm J Community Psychol199018439642264559

- RoseJHA life course perspective on health threats in agingJ Gerontol Soc Work1991178597

- RoseJHInteractions between patients and providers: an exploratory study of age differences in emotional supportJ Psychosoc Oncol1993104367

- RoseJHO’TooleESkeistRComplementary therapies for older patients: an exploratory survey of primary care physicians’ attitudesClin Gerontologist199819319

- RoseJHHaugMBook review: communication and the cancer patient: Information and truthJ Ethics Law Aging19995713

- RoseJHO’TooleEDawsonNVAge differences in care practices and outcomes for hospitalized patients with cancerJ Am Geriatr Soc200048Suppl 5S25S3210809453

- RoseJHBowmanKFDeimlingGHealth maintenance activities and lay decision-making support: a comparison of young-old and old-old long-term survivorsJ Psychosoc Oncol2004222144

- RoseJHO’TooleEEDawsonNVPerspectives, preferences, care practices and outcomes among older and middle-aged patients with late-stage cancerAm J Clin Oncol200422490717