Abstract

Aging per se has a small effect on oral tissues and functions, and most changes are secondary to extrinsic factors. The most common oral diseases in the elderly are increased tooth loss due to periodontal disease and dental caries, and oral precancer/cancer. There are many general, medical and socioeconomic factors related to dental disease (ie, disease, medications, cost, educational background, social class). Retaining less than 20 teeth is related to chewing difficulties. Tooth loss and the associated reduced masticatory performance lead to a diet poor in fibers, rich in saturated fat and cholesterols, related to cardiovascular disease, stroke, and gastrointestinal cancer. The presence of occlusal tooth contacts is also important for swallowing. Xerostomia is common in the elderly, causing pain and discomfort, and is usually related to disease and medication. Oral health parameters (ie, periodontal disease, tooth loss, poor oral hygiene) have also been related to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, bacterial pneumonia, and increased mortality, but the results are not yet conclusive, because of the many confounding factors. Oral health affects quality of life of the elderly, because of its impact on eating, comfort, appearance and socializing. On the other hand, impaired general condition deteriorates oral condition. It is therefore important for the medical practitioner to exchange information and cooperate with a dentist in order to improve patient care.

Introduction

Many functions that are essential and sometimes characteristic to humans are performed by the stomatognathic system; speaking, chewing, tasting, swallowing, laughing, smiling, kissing, and socializing.

Ageing affects oral tissues, as any other part of the human body. However, many age-related changes apparent in mouth and in the functions of the stomatognathic system are secondary to extrinsic factors, other than age per se.

According to the Policy basis for the WHO Oral Health Programme, (a) oral health is integral and essential to general health, (b) it is a determinant factor for quality of life, (c) oral health and general health are interrelated, and (d) proper oral health care reduces premature mortality (CitationPetersen 2003).

Findings in the mouth inform the physician about conditions that might affect the patient’s overall health. On the other hand, systemic diseases and medications can cause oral diseases. Therefore, exchange of information between the physician and the dentist is very important. Moreover, impaired oral function is so common in the elderly that many physicians think that it can not be improved. However, there role to encourage their patients to seek dental help is valuable.

During the last 15-years Gerodontology has been included in the curriculae of many Dental Schools (CitationNitschke et al 2001; CitationMohammad et al 2003; CitationKossioni and Karkazis 2006). Three factors are mainly responsible: (a) the increased number of older persons in the present society, (b) their often complicated general condition that affects dental management, and (c) the changes in the dental disease and needs.

The aim of this paper is to describe the age-related changes in the stomatognathic system, to differentiate between the true age-changes and those related to other factors, to discuss the existing evidence about the interrelation of general health and oral health, and to identify ways to reduce their effect on the daily life of the elderly.

The aging stomatognathic system

The most common oral diseases

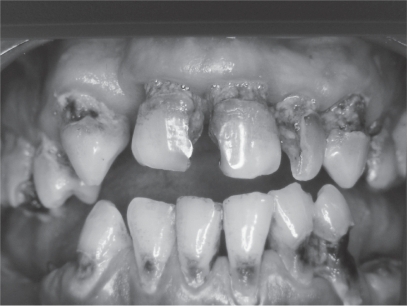

The most common problems in the aging mouth are increased tooth loss (), periodontal disease, dental caries () and oral precancer/cancer (CitationPetersen 2003; CitationPetersen and Yamamoto 2005). Tooth loss is related to periodontal disease, dental caries, impaired general medical condition and socioeconomic factors such as “dental fear”, negative attitude towards oral health, increased cost, reduced access to dental services, low educational background, and low social class. The prevalence of edentulousness in the elderly reported by different studies in the various societies varies (6%–78%) (CitationPetersen 2003). However in many industrialized countries there is a trend towards decline in tooth loss (CitationPedersen and Yamamoto 2005).

Tooth loss is not inevitable as we grow old. Regular visits to the dentist and maintenance of proper oral care can reduce edentulousness.

Motor performance

Age changes in oral motor performance are not as evident as in other parts of the body (CitationBaum et al 1991; CitationKossioni and Karkazis 1995, Citation1998). For example, simple masseteric reflex activity is maintained until very old age (CitationKossioni and Karkazis 1998). This is probably due to continuous use of jaw muscles for chewing, swallowing, speaking, smiling and to the particular functional role of these reflexes in humans.

Age per se has little effect on masticatory performance (CitationHeath 1982; CitationCarlsson 1984). Tooth loss is the main cause of reduced masticatory efficiency and affects food choice.

Although old people wearing dentures present similar patterns of functional adjustments to food consistency with dentate persons, indicating that the role of periodontal ligament mechanoreceptors is taken over by other receptors (CitationKarkazis and Kossioni 1998), their masticatory performance differs in some respects. They have less masticatory strength (CitationHeath 1982; CitationCarlsson 1984), they need more time to chew the food (CitationHelkimo et al 1978; CitationHeath 1982), the movement velocity of the mandible is reduced (CitationJemt 1981) and their masticatory efficiency is reduced by 16%–50% (CitationHeath 1982).

Tooth loss, masticatory performance and diet

Perceived masticatory ability increases with increasing numbers of natural teeth and/or pairs of opposing posterior teeth (CitationKossioni and Karkazis 1999; CitationSheiham et al 1999). People with more than 20 teeth present few chewing difficulties (CitationHelkimo et al 1978; CitationWitter et al 1990; CitationSheiham et al 1999).

People wearing full dentures, or people with extensive tooth loss consume less fruit, vegetables and meat and prefer food that is soft, rich in saturated fats and cholesterols (CitationLaurin et al 1992; CitationJohanson et al 1994; CitationKrall et al 1998). This type of diet is associated with various medical conditions, ie, cardiovascular disease and gastrointestinal cancer.

Moreover, compromised oral health (extensive tooth loss, absence of dentures) has been associated with nutritional deficiencies in very old, institutionalized and frail people, where reduced body mass index and serum albumin concentration have been recorded (CitationMojon et al 1999). In institutions, it is important to include a dentist and a dental hygienist in the care team (CitationMojon et al 1999).

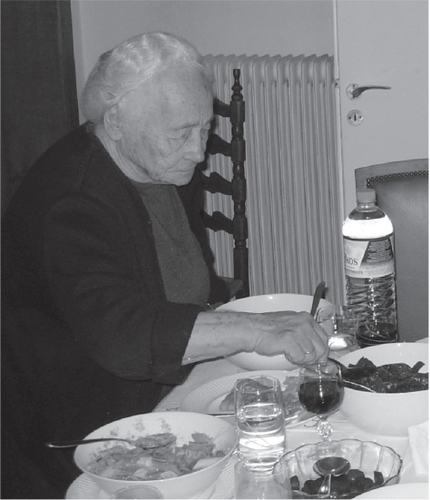

People with dentures have specific difficulties eating hard consistency food (apples, raw carrots, meat), food with seeds which enter under the dentures causing discomfort and pain (tomatoes, grapes) and sticky foods attached to the acrylic dentures’ teeth displacing the dentures (chocolate, gums) (CitationEttinger 1987). Denture problems also lead to social isolation, in order to avoid embarrassment from denture displacement, pain and discomfort during meals. Dental care can control those symptoms and improve quality of life of the edentulous persons ().

However there are studies indicating that the correlation between masticatory variables and dietary selection is weak in the elderly (CitationOsterberg et al 2002), while the improvement of dentures, or the fabrication of new ones have little effect on dietary selection (CitationSandstrom and Lindquist 1987; CitationLaurin et al 1992). It is true that food selection is influenced by various factors such as cost, institutionalization, general medical condition, pain, xerostomia, loneliness, income, knowledge, culture, background etc (CitationHeath 1982; CitationChen and Lowenstein 1984; CitationKossioni and Karkazis 1999; CitationSheiham et al 1999; CitationOsterberg et al 2002). CitationChen and Lowenstein (1984) showed a positive correlation between masticatory problems and nutritional deficiencies and masticatory problems and hypertension, diabetes and ischemic heart disease only in people with a low socioeconomic background, indicating the role of general factors to food intake.

It is therefore very important to include dietary counseling, in order to improve dietary selection in people with compromised dentitions (CitationOsterberg et al 2002).

Xerostomia (oral dryness)

Xerostomia is common in the elderly. Various studies report prevalence of subjective feelings of dry mouth of 12%–28%, which increases to 40%–60% for those living in institutions (CitationNarhi 1994; CitationEttinger 1996; CitationKossioni and Karkazis 1999; CitationField et al 2001). Dry mouth causes severe problems to the oral tissues and function, such as high incidence of caries, gingivitis, difficulties in chewing, swallowing, speaking and tasting, burning mouth, oral pain, oral malodour, increased vulnerability of the oral mucosa to mechanical trauma and microbial infection, and dentures’ discomfort (CitationBaum et al 1991; CitationHaugen 1992; CitationNarhi 1994; CitationSreebny and Schwartz 1997; CitationCassolato and Turnbull 2003; CitationPetersen and Yamamoto 2005).

However, ageing is not the main cause of xerostomia. Xerostomia is usually related to systemic disease, medications and head and neck radiotherapy (CitationHaugen 1992; CitationEttinger 1996; CitationSreebny and Schwartz 1997; CitationCassolato and Turnbull 2003). Many drugs are responsible including: antipsychotics (clozapine, chlorpromazine), tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, imipramine, doxepin), selective serotonine reuptake inhibitors (sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine), antihypertensives (clonidine, methyldopa, prazosin), diuretics (spirnolactone, chlorothiazide, furosemide), sedatives (flurazapam, triazolam, temazepam) (CitationCassolato and Turnbull 2003). They mainly act by inhibiting signalling pathways within salivary tissue and reducing the output of the gland (CitationCassolato and Turnbull 2003).

It is very important to treat xerostomia because this will significantly improve the patients’ quality of life. Treatment includes: regular review of drug regimens, reduction of total number of drugs, substitute xerostomic drugs with alternatives that have less xerostomic effect, modification of drug dose and schedule, intake of systemic cholinergic stimulants (pilocarpine HCL) if no contraindicated, frequent drinking of water and milk, use of saliva substitutes, use of saliva stimulants (chewing sugar free gum, sucking sugar-free lemon candies), avoiding smoking, avoiding dry food and alcohol consumption, frequent dental visits, improvement of denture fitting, improvement of oral hygiene, use of topical fluorides and antibacterial mouthwashes (chlorexidine 0.12%) (CitationEttinger 1996; CitationSreebny and Schwartz 1997; CitationCassolato and Turnbull 2003).

A very close cooperation between the medical doctor and the dentist is imperative to control xerostomia and its side effects. Moreover, the people who are taking care of the frail institutionalized elderly must be informed about the problem and the necessary measures.

Dysphagia (swallowing difficulty)

Normal swallowing is very important to avoid aspiration pneumonia. It is little affected by age (CitationLogemann 1990; CitationBaum et al 1991), but it is affected by disease, xerostomia and unstable occlusion. The tongue and the mandible are stabilized in order to easily swallow hard food. This is best accomplished with the contraction of the jaw elevator muscles and the occlusion of the teeth (CitationZarb et al 1988). Therefore, providing occlusal stability by dental restorative treatment (ie, by fabricating bridges, partial dentures, and full dentures) helps swallowing function in the old age.

Resorption of the alveolar bone

After the extraction of the teeth the alveolar bone is gradually and continuously reducing (CitationKlemetti 1996; CitationKarkazis et al 1997; CitationCarlsson 2004). In the study of CitationKarkazis et al (1997) the overall reduction in the anterior mandibular height was 7.87 mm in a 7-years’ period, but the interindividual variation was increased. The main clinical consequence of this problem is difficulty in the fabrication and functioning of complete dentures. Resorption is more pronounced in the mandible than in the maxilla and there are many old people who do not wear their lower dentures, as they find it difficult to control them.

The interindividual variation in bone loss is significant and the etiology is complex. Many factors have been implicated: ie, age, gender, length of edentulism, denture wearing habits, occlusal loading, nutrition, disease, medication, but the results are not conclusive (CitationKlemetti 1996; CitationPalmqvist et al 2003; CitationPietrokowski et al 2003; CitationCarlsson 2004). Age itself has not yet proven to be of significant importance. Factors that seem to be involved are the female gender, the length of edentulism, pressure from denture wearing, and osteoporosis.

The best treatment of this problem is to prevent it by preserving natural teeth or even roots and construct appropriate prosthetic appliances (ie, overdentures). The placement of dental implants seems to provide functional stimulus to the bone and reduce bone loss (CitationCarlsson 2004).

Oral health and general health

In the recent years there has been increased evidence of an interrelationship between oral and general health. This has been a subject of dispute for many years, and various studies have provided different results, because of the variations in study design, the population studied and the performed analysis (CitationBarnett 2006). It is important to differentiate between results that indicate an association between the two conditions and those that prove a causal relationship (CitationBarnett 2006). The main reason for this discussion is that both noncommunicable chronic diseases and oral diseases may have common risk factors related to lifestyle (eg, smoking, diet) (CitationPetersen 2003; CitationDemmer and Desvarieux 2006).

Oral manifestations of systemic diseases, if early detected, could be extremely beneficial to the patient in terms of diagnosis (eg, microbial infections, immune disorders, nutritional deficiencies) (CitationPetersen 2003).

There is an increasing number of publications on the connection between periodontal disease and diabetes, oral infection and cardiovascular disease and oral infection and bacterial pneumonia. However the results are not clear and conclusive yet.

Inflammation is a common link between periodontal disease and diabetes, and there is some evidence indicating that diabetes is associated with an increased risk of developing periodontal disease, while the effect of periodontal disease on diabetes is less clear (CitationMealey 2006). Patients with diabetes and poor glycemic control have increased risk of developing periodontitis compared to patients with well-controlled diabetes, but periodontal treatment has variant effect on glycemic status (CitationMealey 2006).

Oral health parameters (eg, gingivitis involving bleeding, 1 to 14 natural teeth, xerostomia complaints, low salivary levels of S. Sanguis, positive plaque benzoyl-DL-arginine-naphtylamide test scores) and coronary heart disease have been associated in a convenience sample of 320 US veterans who were at least 60-years of age, but the results can not be generalized (CitationLoesche et al 1998). Regarding periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease there is evidence supporting a moderate relative epidemiological association, more pronounced in younger subjects and stronger for cerebrovascular disease than for coronary disease, but a causal effect is not yet proved (CitationDemmer and Desvarieux 2006). However, although there is no scientific evidence that preventing or treating periodontal disease will reduce cardiovascular disease, periodontal treatment is recommended because of the general benefit to the patients (CitationDemmer and Desvarieux 2006). A significant association has been recorded between tooth loss levels (as a marker of past periodontal disease) and carotid artery plaque prevalence (CitationDesvarieux et al 2003). Periodontal disease and fewer teeth have also been associated to ischemic stroke, but further studies are needed to be conducted to clarify whether those are independent risk factors (CitationJoshipura et al 2003). Incident tooth loss has also been associated with peripheral arterial disease, especially among men with periodontal disease (CitationHung et al 2003).

Institutionalized elderly with respiratory tract infections have significantly higher levels of dental plaque, containing bacteria that can cause chest infections (CitationDepartment of Health 2005). Infections originate from dental plaque on unclean teeth and dentures. Poor oral hygiene and the oral microflora have been specifically related to nosocomial ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia in special-care populations, but there is little evidence of an association between poor oral hygiene and periodontal disease and community acquired pneumonia (CitationScannapieco 2006). The presence of selected oral disorders (edentulous with defective denture bases or generalized stomatitis and dentate with visible calculus (), generalized gingivitis, and teeth with pulpal exposures) associated with low serum albumin (<35 g/L) increased the relative risk of respiratory tract infection to 3.2 (1.5–6.7), while it was 1.9 among subjects with oral problems and ALB > 35 g/L (CitationMojon et al 1997). The incidence of respiratory tract infection in frail institutionalized elderly was greater among dentate subjects and those who consulted a dentist in emergency (CitationMojon et al 1997). Preventive dental care is important in preventing serious lung infections in institutional settings (CitationMojon et al 1997; CitationScanapieco 2006). However the most efficient method is not clear yet (use of topical oral disinfectant with chemotherapeutic agents alone or with mechanical oral hygiene methods) (CitationScannapieco 2006).

Figure 4 Visible calculus on the labial surfaces of the lower teeth of an older female, due to poor oral hygiene.

A multivariate analysis adjusted for general health and lifestyle factors in a cohort born in 1910 in Finland, mostly living at home, has shown that the risk for death of old subjects with urgent need of dental treatment was 3.9 times higher than that of other subjects (CitationHamalainen et al 2005). Urgent need of dental treatment was regarded as pain, infection or condition leading to serious consequences if not treated (ie, chronic periapical abscess, acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, oral abscess, signs of oral cancer). The authors concluded that it is important to diagnose oral infections in time and eradicate them as soon as possible in order to prevent severe complications.

On the other hand, frail elderly often have deteriorated oral care because of impaired vision and manual dexterity, diminished muscle control and oral status susceptible to oral plaque accumulation (CitationWalls and Steele 2001). There are also problems from systemic diseases and medications causing xerostomia, altered smell and taste, and various oral diseases (CitationKossioni and Karkazis 1999, CitationPedersen and Yamamoto 2005).

It is very important to include a dentist and a hygienist in the frail elderly care team and also to educate the nurses and the carers to perform oral hygiene for those who are unable to do it themselves.

Oral health and quality of life

Oral health affects quality of life (CitationMcGrath and Bedi 1999; CitationPedersen 2003; CitationPedersen and Yamamoto 2005).

Old people consider as important the impact of oral health especially on eating, comfort, carefree manner and appearance (CitationMcGrath and Bedi 1999). However, variation is recorded in the preferences between different sexes and social classes (CitationMcGrath and Bedi 1999). More men than women consider eating as important and more women confidence.

A very important factor is tooth loss. It has been related to difficulties in eating, pain, distress and social isolation (CitationJones et al 2003). Old people with more than 20 teeth present had better subjective physical health than those with fewer teeth (CitationAkifusa et al 2005).

Conclusion

There are many changes in the stomatognathic system with aging that can affect quality of life (tooth loss, masticatory problems, xerostomia, dysphagia). Impaired oral health is common, mainly due to the rare visits to the dentist and the often neglected oral hygiene. There is also increased evidence of an association between oral disease and systemic disease, especially in the frail elderly. Thus, exchanging information between the physician and the dentist is important. Oral care (preventive, restorative and surgical) will benefit the elderly. The medical practitioner should pay attention to the oral problems of the older subjects and encourage them to seek dental care.

References

- AkifusaSSohIAnsaiT2005Relationship of number of remaining teeth to health-related quality of life in community-dwelling elderlyGerodontology2291715934350

- BarnettML2006The oral-systemic disease connectionJADA1375S6S17012729

- BaumBJCarusoAJShipJA1991Oral physiologyPapasAChaunceyHGeriatric dentistry Aging and oral healthSt LouisMosby year Book7182

- CarlssonGE1984Masticatory efficiency: the effect of age, the loss of teeth and prosthetic rehabilitationInt Dent J349376376372

- CarlssonGE2004Responses of jaw bone to pressureGerodontology21657015185985

- CassolatoSFTurnbullRS2003Xerostomia: clinical aspects and treatmentGerodontology20647714697016

- ChenMKLowensteinF1984Masticatory handicap, socioeconomic status and chronic conditions among adultsJADA109916186595297

- DemmerRTDesvarieuxM2006Periodontal infections and cardiovascular disease. The heart of the matterJADA13714S20S17012731

- Department of Health2005Meeting the challenges of oral health for older people: a strategic review 2005Gerodontology22Suppl 1911

- DesvarieuxMDemmerRTRundekT2003Relationship between periodontal disease, tooth loss, and carotid artery plaque. The oral infections and vascular disease epidemiology study (INVEST)Stroke342120512893951

- EttingerRL1987Oral disease and its effect on the quality of lifeGerodontics310363305120

- EttingerRL1996Xerostomia: a symptom which acts as a diseaseAge and Ageing25409128921150

- EttingerRLWatkinsCCowenH2000Reflections on changes in geriatric dentistryJ Dent Educ6471572211258859

- FieldEAFearSHighamSM2001Age and medication are significant risk factors for xerostomia in an English population, attending general dental practiceGerodontology1821411813385

- HaugenLK1992Biological and physiological changes in the ageing individualInt Dent J42339481483727

- HamalainenPMeurmanJKauppinenM2005Oral infections as predictors of mortalityGerodontology22151716163906

- HeathMR1982The effect of maximum biting force and bone loss upon masticatory function and dietary selection of the elderlyInt Dent J32345566761273

- HelkimoECarlssonGEHelkimoM1978Chewing efficiency and state of dentitionActa Odont Scand363341273364

- HungH-CWillettWMerchantA2003Oral health and peripheral arterial diseaseCirculation1071152712615794

- JemtT1981Chewing patterns in dentate and complete denture wearers recorded my light-emitting diodesSwed Dent J51992056949328

- JoshipuraKJHungH-CRimmEB2003Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and incidence of ischemic strokeStroke34475212511749

- JohanssonITidehagPLundebergV1994Dental status, diet and cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged people in northern SwedenCommunity Dent Oral Epidemiol2243167882658

- JonesJAOrnerMBSpiroAIII2003Tooth loss and dentures: patients’ perspectivesInt Dent J533273414562938

- KarkazisHCKossioniAE1993Oral health status, treatment needs and demands of an elderly institutionalized population in AthensEur J Prosthodont Rest Dent115763

- KarkazisHCLambadakisJTsiklakisK1997Cephalometric evaluation of the changes in mandibular symphysis after 7 years of denture wearingGerodontology14101510530174

- KarkazisHCKossioniAE1998Surface EMG activity of the masseter muscle in denture wearers during chewing of hard and soft foodJ Oral Rehab25814

- KlemettiE1996A review of residual ridge resorption and bone densityJ Prosthet Dent75512148709016

- KossioniAEKarkazisHC1995Variation in the masseteric silent period in older dentate humans and in denture wearersArchs Oral Biol40114350

- KossioniAEKarkazisC1998Jaw reflexes in healthy old peopleAge and Ageing276899510408662

- KossioniAEKarkazisHC1999Socio-medical condition and oral functional status in an older institutionalized populationGerodontology1621810687505

- KossioniAEKarkazisHC2006Development of a gerodontology course in Athens: a pilot studyEur J Dent Educ10131616842586

- KrallEHayesCGarciaR1998How dentition status and masticatory function affect nutrient intakeJADA129126199766107

- LaurinDBrodeurJ-MLeducN1992Nutritional deficiencies and gastrointestinal disorders in the edentulous elderly: a literature reviewJ Can Dent Assoc58738401333877

- LoescheWJSchorkATerpenningMS1998Assessing the relationship between dental disease and coronary heart disease in elderly US veteransJADA129301119529805

- LogemannJA1990Effects of aging on the swallowing mechanismOtolaryngol Clin North Am231045562074979

- McCordJFWilsonMC1994Social problems in geriatric dentistry: an overviewGerodontology116367750966

- McGrathCBediR1999The importance of oral health to older people’s quality of lifeGerodontology5863

- MealeyBL2006Periodontal disease and diabetes. A two-way streetJADA13726S31S17012733

- MohammadARPreshawPMEttingerRL2003Current status of predoctoral geriatric education in US dental schoolsJ Dent Educ675091412809185

- MojonPBudtz-JorgensenEMichelJ-P1997Oral health and history of respiratory tract infection in frail institutionalised eldersGerodontology149169610298

- MojonPBudtz-JorgensenERapinC1999Relationship between oral health and nutrition in very old peopleAge and Ageing28463810529041

- NarhiTO1994Prevalence of subjective feelings of dry mouth in the elderlyJ Dent Res732058294614

- NitschkeIMullerFIlgnerA2001Undergraduate teaching in gerodontology in Austria, Switzerland and GermanyGerodontology21123915369014

- OsterbergTTsugaKRothenbergE2002Masticatory ability in 80-year-old subjects and its relation to intake of energy, nutrients and food itemsGerodontology199510112542218

- PalmqvistSCarlssonGEOwallB2003The combination syndrome: a literature reviewJ Prosthet Dent90270512942061

- PetersenPEYamamotoT2005Improving the oral health of older people: the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health ProgrammeCommunity Dent Oral Epidemiol33819215725170

- PetersenPE2003The world oral health report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century- the approach of the WHO global oral health programmeCommunity Dent Oral Epidemiol31Suppl 132415015736

- PietrokowskiJHarfinJLevyF2003The influence of age and denture wear on the size of edentulous structuresGerodontology2201005

- SandstromBLindquistLW1987The effect of different prosthetic restorations on the dietary selection in edentulous patientsActa Odont Scand4542383324624

- ScannapiecoFA2006Pneumonia in nonambulatory patients. The role of oral bacteria and oral hygieneJADA13721S25S17012732

- SheihamASteeleJGMarcenesW1999The impact of oral health on stated ability to eat certain foods; findings from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of Older people in Great BritainGerodontology16112010687504

- SreebnyLMSchwartzSS1997A reference guide to drugs and dry mouth – 2nd editionGerodontology1433479610301

- WallsAWGSteeleJG2001Geriatric oral health issues in the United KingdomInt Dent J51183711561877

- WitterDJCramwinckelABvan RossumGMJM1990Shortened dental arches and masticatory abilityJ Dent1818592212200

- ZarbGAMohlNDMackayHF1988Deglutition, respiration and speechMohlNDZarbGACarlssonGEA textbook of occlusionChicagoQuintessence Publishing Co Inc15360