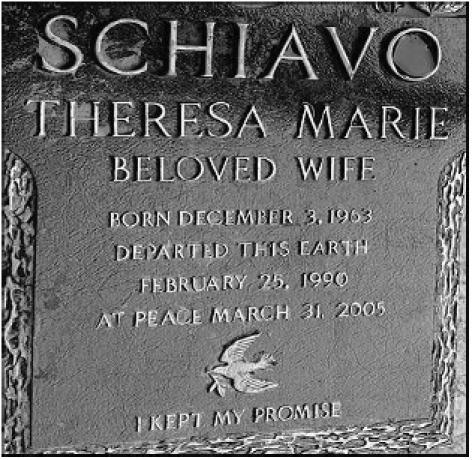

At age four, my eldest son once asked me “Daddy, how old are people when they die?”. I allowed “As old as they are going to get”. In this, Theresa Marie Schiavo, who died at 41, is no different from Pope John Paul II, who died at 87. They were each as old as they were going to get. One died as a consequence of an express decision to remove a medical intervention, the other as a consequence of the natural course of illness.

In late October of 2003, I was appointed by the State of Florida to serve as the Special Guardian ad Litem to Theresa Maria Schiavo, subsequent to a specially enacted Florida Law (Terri's Law). I was charged with reviewing the then 14 years of medical and legal history and documentation in the case, and reporting to the Governor and the courts as to the feasibility of conducting additional tests. To accomplish this, I reviewed more than 30000 pages of legal and medical documents, visited frequently with my ward, Ms Schiavo, and worked with her family and attorneys. My interactions with Ms Schiavo were very direct and intimate: I would visit her for as long as four hours at a time, sometimes more than once a day. I would hold her hand, stroke her hair, hold her head in my hands, and seek some evidence that she was capable of responding, rather than merely exhibiting reflexive behaviors. I begged and cajoled her, played music for her, and asked her parents to help me elicit responses. I had only thirty days to prepare my final report.

Ms Schiavo lived to be 41 years old, but her conscious awareness and interaction during life lasted for only 26 of those years. At the age of 26 she suffered a cardiac arrest that led to profound brain damage, resuscitation, a tracheotomy and respirator-assisted breathing, insertion of a gastric feeding tube, a subsequent month-long coma, followed by fifteen years in what was early and consistently diagnosed as being a persistent vegetative state (PVS).

During the first four years following Ms Schiavo's accident, extensive efforts were deployed to rehabilitate her. She was given intense physical and occupational therapy and was brought to California by her husband to have experimental electrodes implanted in her brain. None of this elicited positive responses or anything other than continued prognoses of no reasonable medical hope of recovery. Her husband and her parents did not embrace that prognosis, but did not categorically refute it until some years later.

Prior to her collapse in the early hours of a February morning in 1990, the Schiavos had spent nearly a year and a half seeking fertility counseling from an obstetrician. They very much wanted children, but were having difficulty. For years prior to that, there is undisputed evidence that Ms Schiavo had succeeded in battling a significant weight problem. By the time she was 18, she weighed 250 pounds, and decided to change her life. Six years into her marriage to Michael, she had achieved a weight of only 110 pounds, and there remains circumstantial evidence that she may have had an eating disorder. Indeed, after her collapse, Mr Schiavo sued the fertility specialist for failing to adequately assess his wife's physical health and her probable eating disorder. It was a long-shot case, but nearly four years after her accident, a jury awarded over a million US dollars to the couple: $300 000 to Mr Schiavo for loss of consortium, and more than $700 000 to Ms Schiavo for maintenance, given the futility of her circumstance. From that point forward, a world of change occurred in the lives of the Schiavos and Theresa's parents, the Schindlers.

For the next 11 years, the families would exercise their hostilities in court: the Schindlers seeking to remove Michael from guardianship over his wife; and Michael protecting what he consistently stated to be his wife's best interests and specific intentions. It got nasty and then nastier. In the end, Ms Schiavo became somebody known about around the world, but known to only a few. Her parents succeeded in garnering the active support of the Governor of Florida, the Florida Legislature, the Congress of the United States, the President of the United States, and Pope John Paul II. All this was done while now common photos and home videos of her partially clad, patently disabled body were projected on tabloids and television screens. All of this was done without her awareness or knowledge.

Only the courts, at the state and federal levels, stood firm in a position on Ms Schiavo. In the face of extraordinary measures by state and federal legislators and chief executives, the local circuit court was joined by state and federal courts of appeal and the supreme courts in upholding Ms Schiavo's right, through the evidence provided, not to remain in her state and to be allowed to have her feeding tube removed and die.

What was the value of the clinical information and the clinical interventions deployed in Ms Schiavo's case? How did these data coincide with the law? And what happens when there is a disconnect between clinical standards and decisions that cause the ultimate aging phenomenon: death?

Here is the dilemma in a nutshell. The technical standards of evidence in each state's judicial system vary around the issue of how to determine an individual's intentions about end-of-life decisions. But the medical science underlying the determination of neurological states should be far more consistent. By this is implied that there should be clear and convincing, empirically derived clinical guidelines and measures for specific medical conditions, such as “persistently vegetative”.

Is it reasonable to assume that standards developed by national organizations, such as the American Academy of Neurology (AAN); and statutes crafted following years of bipartisan efforts, such as the Florida guardianship laws, should serve as the guidelines against which life and death decisions shall be made when there is controversy among family members or between families and institutions/providers? Dr Ronald Cranford, the distinguished neurologist who provided expert opinions in the cases of Karen Ann Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and Theresa Schiavo, points to the professionally crafted AAN guidelines as the gold standard for assessing persons in PVS. Yet PVS itself has been subjected to allegations of nebulous and even misapplication by some neurologists and many others, particularly in light of claims that there exists a “minimally conscious state” or “locked-in syndrome” which might be missed.

According to Florida law, persons diagnosed with PVS fall into the same category as those with terminal and end-of-life disease states. This became important in Ms Schiavo's case because of the reasonable issues surrounding care, continuation of care, interventions versus maintenance, and most vitally, decisions to end life. And these factors, despite what may be consistent scientific definitions of a disease, will always be subject to distinctive state laws regarding how decisions about end-of-life can be made.

For example, in the case of Nancy Cruzan, Ms Cruzan had clearly articulated an intention not to be kept alive in her severely debilitated state following a horrific car accident. But that articulation was verbal and not written; it was not memorialized in the particular fashion required by Missouri law. For that reason, while the US Supreme Court recognized the nature of her condition and the futility of her circumstance; and further acknowledged that she may have articulated an intent, they placed express Missouri law above the science and medical guidelines. The Cruzan case clearly established that the laws of the individual states would serve as the bases for the application of the medical science.

That is why in the case of Ms Schiavo, the nexus seemed for many to favor a relatively easy resolution of the dispute that emerged between her parents and her husband over the latter's decision to help Ms Schiavo die by removing her feeding tube. And this is where the vicissitudes of law and medicine formed a sticky nexus that to this day has created monstrous political, spiritual, and even clinical chasms across America over end-of-life applications.

Ms Schiavo did not have a formal, written, executed advance directive. She did not have a healthcare surrogate authorizing anybody to make decisions in her stead; and she did not have a living will articulating in writing her intentions regarding heroic measures, clinical interventions, or her wish with respect to being kept alive by artificial means if she were in a diagnosed persistent vegetative state. But Florida law provides for means by which Ms Schiavo's intentions were established.

First, Mr Schiavo had been formally appointed by the Florida courts to serve as his wife's legal guardian shortly after the accident, and this was undisputed by her parents. In fact, for nearly four years, Mr Schiavo worked closely with his in laws to provide care and attention to the common object of their affections, Theresa. By virtue of this guardianship status, Mr Schiavo was empowered, in Florida, to make many decisions about his wife, her property, and her care. But he could not independently make the decision to terminate her artificial nutrition.

Second, Mr Schiavo placed into evidence statements made by his wife, prior to her accident, overheard by him and other witnesses. These statements established that Ms Schiavo had expressed a clear intention not to be kept alive if she were ever to be in a permanently unconscious state. While the validity of these statements was challenged by Ms Schiavo's parents, the Florida courts determined that they represented credible evidence of Ms Schiavo's intentions; that the credibility was clear and convincing; and that the Florida Rules of Evidence supported their admission and acceptance.

Third, once these intentions had been established, then Mr Schiavo was able to exercise “substituted judgment” on behalf of his wife, acting in her “best interests”. This is a key to what followed, because it then brought in the element of medical judgment, in part as a formality, to establish that Ms Schiavo was, in fact, in a PVS. At that juncture, the war of the experts was initiated: something common in many court battles, but particularly colored in this case because of the nature of the clinical evidence and the science.

The diagnosis of PVS is not based upon blood tests or radiographs or other mechanical/electrical tests. Rather, it is a functional diagnosis that is made by the physician in concert with those tests, and is predicated on the physician's determinations that the patient meets the functional clinical checkpoints of the American College of Neurology.

And this is where the good science and medicine began to melt in the face of hope, beliefs, and value sets that disagreed substantively and vehemently with the very principle of allowing a living human being to be removed from any extant form of life support and allowed to die. As Ms Schiavo's parents stated during court proceedings, even if Ms Schiavo had executed a living will, they would have sought to nullify it because of their beliefs and their attested certainty about her beliefs regarding termination of life.

The point here is that the science and the medical guidelines became irrelevant in the face of belief systems that rejected them as inhuman and unconscionable. That is in great part why Florida's Governor Jeb Bush took such a strong and visible stand against the removal of the artificial feeding tube and continued to fight for her parent's right to keep her alive.

The disconnect here is that in the face of the science and medicine that established her condition, and the state law that had carved out how decisions may be made for persons in that condition, it took eleven years, court challenges, state and federal laws, papal statements, and the engagement of political forces at the highest levels before a conclusion was reached in the singular life of Ms Schiavo. And that conclusion was predicated expressly upon the judgment of the state and federal court systems that:

the specific scientific bases upon which Ms Schiavo had been diagnosed as being in a persistent vegetate state were valid (ie, the AAN guidelines);

Florida Law clearly established artificial nutrition as a medical intervention that could be removed in particular instances where PVS and the intention of the patient not to be maintained by artificial means were established;

the testimony of physician experts establishing that Ms Schiavo was PVS met the “clear and convincing” evidentiary level required by Florida law;

the evidence supporting Mr Schiavo's substituted judgment to remove her feeding tube was “clear and convincing”.

Indeed, the court system remained singularly consistent in its determination of the above, even though it afforded exquisite flexibility to Ms Schiavo's parents, allowing them to re-file same or similar motions for years.

So, the accepted clinical guidelines were applied and the law was followed. Ms Schiavo's artificial feeding tube was removed, for the third time, during Easter week of 2005, in the midst of additional international drama over the death of Pope John Paul II. The Pope, some months earlier, had issued a non-encyclical statement admonishing against the removal of artificial nutrition. On the day that Ms Schiavo's feeding tube was removed, his was inserted. Ms Schiavo died 13 days later, and then the Pope's death took over the national media stage.

Ms Schiavo's autopsy revealed what many close to the case clinically knew all along: the degree of atrophy and damage to her brain was profound, indeed, greater than some had predicted. Contrary to desperate allegations, there was no evidence of trauma. And the medical examiner could not categorically state the reason for her initial collapse, though a significant electrolyte imbalance due to bulimia was not ruled out. It was not possible to confirm the diagnosis of PVS, which requires a functional assessment in concert with other tests. So the prevailing expert opinions stood.

Ms Schiavo was as old as she was going to get when she died. Her husband and many others, argue that she “left this world” the night of her collapse in 1990. Her parents and their supporters, argue that she was killed: starved to death because of her inability to interact and her dependence on a simple plastic tube for food and water.

Standards of care and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment were followed and incorporated into the carefully crafted laws of the State of Florida. Had Ms Schiavo lived in Missouri, New Jersey, or New York State, she would not have been subject to the substituted judgment rule and she would be kept alive. In a healthcare system where we give some considerable lip service to evidence-based criteria and consistent outcomes, how do we square the application of these in the prevention or management of “maladaptive correlates of aging”? Indeed we can be right and wrong at the same time. We can do the right thing and achieve results that create not only dissonance within our society, but substantive questions about what we are really up to.

These matters take on increasing importance as we face the challenges of allocating scarce resources to an aging population. This topic has come in and out of political favor in the States, and has remained rather dormant since the early 1990s. A US public radio commentator, Daniel Schorr noted that perhaps Ms Schiavo will “unconsciously” cause us to revisit the rapidly growing challenges of resource decisions.