Abstract

Interventions to reduce mortality and disability in older people are vital. Aspirin is cheap and effective and known to prevent cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, many cancers, and Alzheimer dementia. The widespread use of aspirin in older people is limited by its gastrointestinal side effects. Understanding age-related changes in gastrointestinal physiology that could put older people at risk of the side effects of aspirin may direct strategies to improve tolerance and hence lead to greater numbers of older people being able to take this effective intervention.

Introduction

As the population ages, clinical and cost effective strategies to increase lifespan whilst reducing disability are becoming a major public health agenda. The cyclooxygenase inhibitor aspirin has the potential to be such a strategy, as it is a simple, cheap intervention that is increasingly recognized as preventing a wide range of diseases associated with significant morbidity, and as a result will ensure healthy life into older age.

Evidence for the benefits of aspirin is now so overwhelming that strategies to deliver it to as many older people as possible are a health promotion priority. Many cancers, strokes, myocardial infarctions, and cases of Alzheimer dementia might be prevented if more older people could benefit from the risk reductions of aspirin.

Evidence supporting the benefits of aspirin

Aspirin is one of the most frequently prescribed medications for older people (CitationScomerville et al 1986). It is taken to control inflammation in arthritis, but more importantly has been shown in meta-analyses to reduce events in those at risk from cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease (CitationAntiplatelet Trialists Collaborative 2002; CitationHayden et al 2002). There is also emerging evidence that aspirin use protects against Alzheimer dementia and a wide range of cancers including breast, esophageal, prostate, colorectal, and lung carcinomas (CitationDubois et al 1998; CitationSmith et al 2000; CitationBardou et al 2004).

Mathematical modeling confirms that the beneficial effects of aspirin are potentially so great that encouraging low-dose aspirin use in all 50-year-old subjects would reduce disability and double the chances of living a healthy life into old age (CitationMorgan 2003). Many studies are now suggesting that the benefits of long-term low-dose aspirin outweigh the risks (CitationEidelman et al 2003). In the elderly, these benefits are to an extent similar to, and often greater than, that observed in younger age groups (CitationDornbrook et al 2003). However, the studies necessary to acquire such data in older age groups will require huge numbers such as that seen in the ongoing Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) study with 15000 subjects aged over 70 being followed for 5 years (CitationNelson et al 2003).

Despite the acknowledged benefits of aspirin, a cross-sectional population survey found only 7.1% were taking aspirin as a primary preventative measure (CitationTrinder et al 2003). Furthermore, of those prescribed aspirin for secondary prevention, 8% were no longer taking it at 6-month follow up, presumably because of side effects (CitationEagle et al 2004).

Gastrointestinal adverse effects of aspirin

The widespread use of aspirin by older people has historically been limited as many develop abdominal side effects. Almost 50% of those prescribed aspirin for secondary prevention report gastrointestinal symptoms after just 2 weeks of use (CitationLaheij et al 2001; CitationNiv et al 2005) and almost one-third of aspirin users have endoscopically visible lesions within one hour of ingestion (CitationHawkey et al 1991; CitationCole et al 1999). Symptoms are recognized as a poor predictor for gastrointestinal lesions with 48% of asymptomatic aspirin users having lesions visible at endoscopy.

Aspirin can lead to adverse gastrointestinal effects ranging from dyspepsia with endoscopically normal gastric mucosa, asymptomatic and symptomatic lesions such as erosions and ulcers, and complications of ulcers including bleeding and perforation. Although these gastrointestinal effects are dose dependant, even lower doses of aspirin are being increasingly recognized as a cause of gastrointestinal bleeding (CitationStack et al 2002).

It is controversial, however, whether simply being old makes you more susceptible to aspirin-induced gastrointestinal damage or whether comorbidity, comedications, and past history are more important predictors of toxicity than age and perhaps more relevant to therapeutic decision making in this population (CitationSolomon and Gurwtiz 1997). Risk factors for aspirin-induced gastrointestinal complications are shown in .

Table 1 Risk factors for aspirin-induced gastrointestinal complications

Developing strategies to improve tolerability of aspirin

Gastrointestinal side effects of aspirin occur more frequently in older people (CitationAalykke 2001). Therefore strategies to improve tolerability might be directed in two ways: at those specific physiological abnormalities that identify individuals who are less able to tolerate aspirin irrespective of their age, and at age-related changes in gastrointestinal physiology that might predict why older people tolerate aspirin less well compared with younger age groups (). This review will focus primarily on this second strategy.

Table 2 Potential strategies to improve tolerability of aspirin in older people

Strategies to improve tolerability: the eradication of Helicobacter pylori

Many changes in gastrointestinal physiology once thought to be primary effects of aging have been reexamined since the discovery of the microorganism Helicobacter pylori (CitationKateralis et al 1993; CitationFeldman et al 1996). Infection with H. pylori itself induces changes in gastrointestinal physiology, which is of relevance when it is appreciated that in the Western world infection rates increase with age, with up to 80% of 80-year-old subjects infected (CitationMarshall 1994).

Both aspirin use and H. pylori infection cause peptic ulcers, but whether the incidence is greater when both are present is unclear (CitationVoutilainen et al 2001). H. pylori and aspirin are independent risk factors for ulceration in all age groups (CitationLanas et al 2002), however, studies specifically involving older people suggest that there may be a synergistic effect on risk (CitationNg et al 2000; CitationSeinela and Ahvenainen 2000).

Low doses of aspirin induced endoscopically visible upper gastrointestinal mucosal damage more frequently in H. pylori positive subjects (50%) compared with 16% of H. pylori negative volunteers (CitationFeldman et al 2001). Furthermore, eradication of H. pylori reduces damage caused by low doses of aspirin and recurrence of ulcers during aspirin use (CitationMcCarthy 1998) and improves adaptability of the gastrointestinal tract to aspirin (CitationKonteruk et al 1997, Citation1998). Unfortunately, H. pylori eradication will not always improve aspirin tolerability, as gastrointestinal symptoms, ulcers, and their complications are associated with aspirin use in those with, and without, H. pylori infection (CitationSeinela and Ahvenainen 2000).

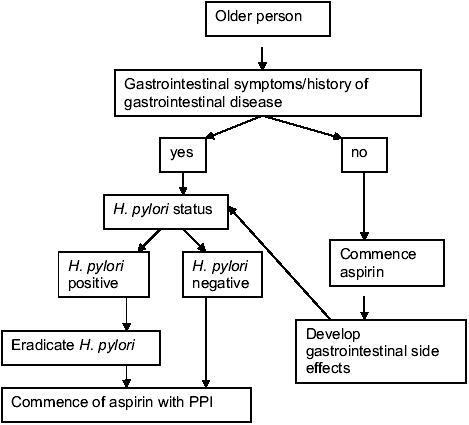

Despite this, it would seem pragmatic to recommend eradication of H. pylori infection prior to commencing long-term aspirin treatment. Whether or not this approach is appropriate in all older people, irrespective of symptoms, or only in those with gastrointestinal symptoms or a history of peptic ulceration (CitationNICE 2005) requires large studies in older people and should include evaluation of aspirin tolerance after H. pylori eradication ().

Structural changes with age in the upper gastrointestinal tract could affect tolerance of aspirin

Gastrointestinal transit time, in particular gastric emptying, is slower in older people (CitationBrogna et al 1999), which potentially increases exposure of the gastric mucosa to ingested drugs. Such direct toxic effects provide the rationale for the use of enteric-coated aspirin. Theoretically, influencing the time of exposure to, or the formulation of, aspirin preparations, or reversing the age-associated decline in gastrointestinal transit time, may influence the ability of older people to tolerate aspirin.

Atrophy of the gastric mucosa incidence increases with age (CitationJames 2000) partly because of the increased prevalence of H. pylori in older people. Gastric atrophy results in smaller volumes of less acidic gastric juice in the stomach lumen. This reduced ability to dilute ingested drugs will potentially increase the risk of direct gastrointestinal toxic side effects. Further study is required to determine whether widespread H. pylori eradication programmes would decrease gastric atrophy prevalence in older people and allow better tolerance of aspirin.

Improving tolerance of aspirin by addressing age-related changes in gastrointestinal physiology

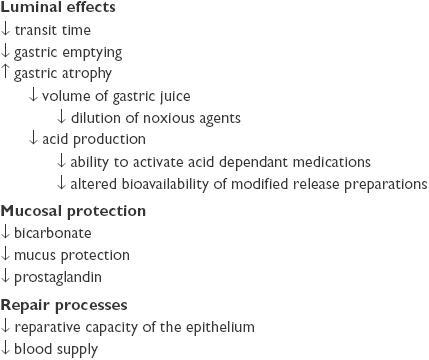

There is limited research examining age-related changes in the human upper gastrointestinal tract that might explain why older people tolerate aspirin less well. What is currently known about changes in physiology in the older stomach and duodenum is summarized in . An understanding of these changes in gastric physiology with age could direct interventions that lead to improved tolerance.

In the human gastrointestinal tract there is a balance between aggressive factors (gastric acid and pepsin) and mucosal protective mechanisms (mucus and bicarbonate). Current evidence does not suggest that the increase in dyspeptic symptoms or ulceration in older people taking aspirin is related to an age-related increase in the aggressive factors: gastric acid or pepsin. Gastric acid secretion may be reduced in older people due to the increase in gastric atrophy, and pepsin output is also lower (CitationFeldman et al 1996). However, age-related deficiencies in the ability of the mucosa to protect and repair itself have been documented, and any additional depletion due to medication such as aspirin will further increase mucosal vulnerability (CitationGuslandi et al 1999).

Gastrointestinal mucosal protective molecules such as prostaglandins decline with advancing age (CitationCryer, Lee, et al 1992; CitationCryer, Redfern, et al 1992; CitationGoto et al 1992; CitationLee and Feldman 1994). Prostaglandins stimulate protective mechanisms such as mucus and bicarbonate whilst aspirin inhibits prostaglandin production and causes gastric damage (CitationSababi et al 1995). The lower levels of prostaglandins in the gastric mucosa of older people makes them more susceptible to damage by a further reduction in prostaglandin synthesis caused by aspirin.

The first line of mucosal protection from exogenous toxins and luminal acid and pepsin is the mucus gel layer. Studies have shown both a quantitative reduction in mucus production with age and impaired quality of the mucus (CitationCorfield et al 1993; CitationFarinati et al 1993; CitationNewton, Jordan et al 2000), and as a result an increased susceptibility to damage by aspirin (CitationCorfield et al 1993).

The ability of the gastric mucosa to protect itself by repelling toxins is independently decreased in association with H. pylori induced gastritis and NSAID use (CitationGoddard et al 1987; CitationSpychal et al 1990) and also with aging (CitationHackelsberger et al 1998). It is not clear whether these factors work synergistically.

There is also an age-related decline in the ability of the gastrointestinal mucosa to neutralize luminal acid by bicarbonate secretion (CitationKim et al 1990; CitationLee 1997; CitationFeldman et al 1998; CitationGuslandi et al 1999). The older stomach is also less able to repair itself after damage (CitationLee et al 1998; CitationLiu et al 1998), which when taken with the antithrombotic effects of aspirin may account for gastrointestinal side effects. Control of the repair processes is poorly understood but does have the potential to be manipulated (CitationMajumdar et al 1997). Trefoil proteins are a family of mucosal repair proteins thought to be important in gastrointestinal protection (CitationMay and Westley 1997). Trefoil factor family 1 (TFF1)and TFF2 are expressed in the stomach and TFF2 and TFF3 are expressed in the duodenum. TFF1 is intimately associated with gastric mucus (CitationNewton, Allen, et al 2000) and gastric concentrations of TFF2 show a circadian variation (CitationSemple et al 2001) increasing dramatically at night. Recent work by our group has shown that the nocturnal peak of mucosally protective TFF2 is lower and earlier in older people (CitationJohns et al 2005), and manipulating the nocturnal increase of cytoprotective TFF2 or encouraging patients to take aspirin at night when the mucosal protective mechanisms are optimal may improve tolerability.

In animals, a reduction in basal gastric blood flow (CitationLee 1996) and an attenuation of gastric blood flow in response to injury has been observed with age (CitationGronbech and Lacy 1994; CitationMiyake et al 1996), though this is controversial (CitationTaha 1993). If there are reductions in gastric blood flow in older people, coprescription of the vasodilator nitric oxide with aspirin (NO-NSAID) may have potential (CitationWallace et al 1995).

Strategies known to reduce gastrointestinal complications of aspirin in older people

Studies carried out specifically in older age groups have shown in both acute and chronic users of aspirin, that concomitant use of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) reduces the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (odds ratio [OR] 1.12 chronic, 1.05, acute) (CitationPilotto et al 2003) and risk of peptic ulcer disease (CitationPilotto et al 2004).

This benefit from PPI coprescription with aspirin is greater than with either the prostaglandin analog misoprostol (OR 1.91) and H2 blockers (OR 2.26). This has prompted the recommendation that PPI cotreatment is advisable in symptomatic older patients who need treatment with aspirin. However, whether a similar approach is appropriate for primary prevention of complications in asymptomatic older people requiring aspirin needs study.

In addition, although the studies confirm that both PPI and misoprostol are effective at reducing the risk of ulcer recurrence (CitationGoldstein et al 2004), this does not guide clinical practice when confronted with a patient who simply develops gastrointestinal symptoms (rather than complications) after commencing aspirin.

Some have suggested that in high-risk patients with aspirin-associated peptic ulcer disease, conversion to other antiplatelet therapies such as clopidogrel may be appropriate. However, studies suggest that complication rates with clopidogrel are no better than continuation of aspirin alone (CitationNg et al 2004), with studies confirming that aspirin plus PPI is superior to clopidogrel in the prevention of recurrence (CitationChan et al 2005).

Patients taking long-term, low-dose aspirin who have had ulcer complications respond to acid suppressive treatments such as a PPI after eradication of H. pylori (CitationLai et al 2002), but eradication alone may be superior to the use of a PPI (CitationChan et al 2001). It should be remembered that coprescription of acid suppressive treatments with aspirin to improve tolerability in older people is unlikely to be the whole answer as physiologically there is no age-related increase in acid.

Future directions

Damage to the gastrointestinal mucosa is related to aspirin dose (CitationMoore et al 1989, Citation1991) and lower doses of aspirin have fewer side effects (CitationSerrano et al 2002). Therefore, it may be that some aspirin is better than no aspirin, and studies in older age groups would determine whether smaller doses of aspirin could be tolerated and give some, if not all, of the benefits obtained with larger doses in younger age groups. In the past, treatment of those who developed adverse side effects was terminated. The evidence for the use of aspirin is now so overwhelming that we need to consider how to give some aspirin to as many people as possible.

There are huge implications for allowing greater numbers of older people to benefit from taking aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, Alzheimer dementia, and cancer. Defining the underlying age-related changes in physiology that make the older gastrointestinal tract susceptible to damage will identify targets for therapy. Reducing deficiencies in mucosal repair proteins, such as growth factors and trefoil proteins, may improve the reparative process. Delineating the pathways of action of these molecules in older people is therefore important. Conceptually simple strategies such as reducing the prevalence of gastric atrophy or reversing the age-associated decline in gastric emptying may also be effective.

Conclusion

Aging of the stomach and duodenum is an important but poorly understood area of gerontology. In older people, the major causes of mortality and morbidity are cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, gastrointestinal cancers, and dementia. Understanding how aspirin reduces risk in these diseases and whether or not older people are intrinsically at risk of side effects because of age-related changes in gastrointestinal physiology should allow greater numbers of older people to benefit from the risk reductions associated with taking aspirin. Research in this area could be translated directly into the clinical setting and potentially make a real impact upon the quality of life of older people.

References

- AalykkeCLauritsenKEpidemiology of NSAID-related gastroduodenal mucosal injuryBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol20011570422

- Antiplatelet Trialists CollaborationCollaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction and stroke in high risk patientsBMJ2002324718611786451

- BardouMBarkunANGhosnJEffect of chronic intake of NSAID and cyclooxygenase 2 selective inhibitors on oesophageal cancer incidenceClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20042880715476151

- BrognaAFerraraRBucceriAMInfluence of ageing on gastrointestinal transit time: an ultrasonographic and radiologic studyInvest Radiol199934357910226848

- ChanFKChingJYLHungLCTClopidogrel versus aspirin and esomeprazole to prevent recurrent ulcer bleedingNEJM20053522384415659723

- ChanFKChungSCSuenBYPreventing recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection who are taking low dose aspirin or naproxenNEJM20013449677311274623

- ColeATHudsonNLiewLCProtection of human gastric mucosa against aspirin – enteric coating or dose reduction?Aliment Pharmacol Ther1999131879310102949

- CorfieldAPWagnerSASafeASialic acids in human gastric aspirates: detection of 9-O-lactyl-and 9-O-acetylneuraminic acids and a decrease in total sialic acid concentration with ageClin Sci19938457398504635

- CryerBLeeEFeldmanMFactors influencing gastroduodenal mucosal prostaglandin concentrations: roles of smoking and agingAnn Intern Med1992116636401546863

- CryerBRedfernSGoldschiedtMEffect of aging on gastric and duodenal mucosal prostaglandin concentrations in humansGastroenterology19921021118231551520

- DornbrookLKAPieperJARothMTPrimary prevention of coronary heart disease in the elderlyAnn Pharmacother20033716546314565805

- DuboisRNAbramsonSBCroffordLCyclooxygenase in biology and diseaseFASEB J1998121063739737710

- EagleKAKlineREGoodmanSAdherence to evidence based therapies after discharge for acute coronary syndromes: an ongoing prospective observational studyAJM20041177381

- EidelmanRSHebertPRWeismanSMAn update on aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseaseArch Inter Med2003163200610

- FarinatiFFormentiniSDella LiberaGChanges in parietal cell and mucous cell mass in the gastric mucosa of normal subjects with age: a morphometric studyGerontology199339146518406057

- FeldmanMCryerBEffects of normal aging on gastric non-parietal fluid and electrolyte secretion in humansGerontology19984422279657083

- FeldmanMCryerBMallatDRole of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastrointestinal injury and gastric prostaglandin synthesis during long term/low dose aspirin therapy: a prospective placebo-controlled, double blind randomized trialAm J Gastroenterol2001961751711419825

- FeldmanMCryerBMcArthurKEEffects of aging and gastritis on gastric acid and pepsin secretion in humans: a prospective studyGastroenterology19961101043528612992

- GalleraniMSimonataMManfrediniRRisk of hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal tract bleedingJ Clin Epidemiol2004571031015019017

- GoddardPJHillsBALichtenbergerLMDose aspirin damage canine gastric mucosa by reducing surface hydrophobicityAm J Physiol1987252G421303826379

- GoldsteinJLHuangBChristopoulosNGUlcer recurrence in high risk patients receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs plus low dose aspirin: results in post hoc subanalysisClin Ther20042616374315598480

- GotoHSugiyamaSOharaAAge associated decreases in prostaglandin contents in human gastric mucosaBiochem Biophys Res Commun1992186144381510674

- GronbechJELacyERImpaired gastric defense mechanisms in aged rats: role of sensory neurons, blood flow, restitution and prostaglandinsGastroenterology1994106A84

- GuslandiMPellegriniASorghiMGastric mucosal defences in the elderlyGerontology199945206810394077

- HackelsbergerAPlatzerUNiliusMAge and Helicobacter pylori decrease gastric mucosal surface hydrophobicity independentlyGut19984346599824570

- HawkeyCJHawthorneABHudsonNSeparation of the impairment of homeostasis by aspirin from mucosal injury in the human stomachClin Sci199181565731657506

- HaydenMPignoneMPhillipsCAspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a summary of evidence for the US Preventive Services Task ForceAnn Intern Med20021361617211790072

- JamesOFWGrimley-EvansJFranklin-WilliamsTThe stomachThe Oxford textbook of geriatric medicine2000OxfordOxford Univ Pr.179256

- JohnsCENewtonJLWestleyBRThe diurnal rhythm of the cytoprotective trefoil protein TFF2 is reduced by factors associated with gastric morbidity: ageing, Helicobacter pylori infection and sleep deprivationAm J Gastroenterol20051001491715984970

- KateralisPHSeowFLinBPCEffect of age, Helicobacter pylori infection, gastritis with atrophy on serum gastrin and gastric acid secretion in healthy menGut199334103278174948

- KimSWParekhDTownsendCMEffects of aging on duodenal bicarbonate secretionAnn Surg199021233282396884

- KonterukJWDeminskiAKonturekSJHelicobacter pylori and gastric adaptation to repeated aspirin administration in humansJ Physiol Pharmacol199748383919376621

- KonterukJWDeminskiAKonturekSJInfection of Helicobacter pylori in gastric adaptation to continued administration of aspirin in humansGastroenterology1998114245559453483

- LaheijRJJansenJBVerbeekALHelicobacter pylori infection as a risk factor for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients using aspirin to prevent ischaemic heart diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther2001151055911421882

- LaiKCLamSKChuKMLansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term low-dose aspirin useNEJM20023462033812087138

- LanasAFuentesJBenitoRHelicobacter pylori increases the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking low-dose aspirinAliment Pharmacol Ther2002167798611929396

- LeeMAge-related changes in gastric blood flow in ratsGerontology1996422903

- LeeMThe aging stomach: implications for NSAID gastropathyGut19974142569391235

- LeeMFeldmanMAge-related reductions in gastric mucosal prostaglandin levels increase susceptibility to aspirin-induced injury in ratsGastroenterology19941071746507958687

- LeeMHardmanWECameronIAge-related changes in gastric mucosal repair and proliferative activities in rats exposed acutely to aspirinGerontology1998441982039657079

- LiuLTunerJRYuYDifferential expression of EGFR during the early reparative phase of the gastric mucosa between young and aged ratsAm J Physiol1998275G943509815022

- MajumdarAPFligielSEJaszewskiRGastric mucosal injury and repair: effect of ageingHistol Histopathol1997124915019151138

- MarshallBJHelicobacter pyloriAm J Gastroenterol199489S116288048402

- MayFEBWestleyBRTrefoil proteins: their role in normal and malignant cellsJ Pathol1997183479370940

- McCarthyDMHelicobacter pylori and non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs: does infection affect the outcome of NSAID therapy?Yale J Biol Med1998711011110378355

- MilaniSCalabroARole of growth factors and their receptors in gastric ulcer healingMicrosc Res Tech2001533607111376497

- MiyakeHInabaNKatoSIncreased susceptibility of rat gastric mucosa to ulcerogenic stimulation with aging: role of capsaicin sensitive sensory neuronsDig Dis Sci199641339458601380

- MooreJGBjorkmanDJNSAID-induced gastropathy in the elderly: understanding and avoidanceGeriatrics1989445172666269

- MooreJGBjorkmanDJMitchellMDAge does not influence acute aspirin-induced gastric mucosal damageGastroenterology1991100162692019367

- MorganGA quantitative illustration of the public health potential of aspirinMed Hypotheses200360900212699722

- NelsonMReidCBeillinLRationale for a trial of low dose aspirin for the primary prevention of major adverse cardiovascular events and vascular dementia in the elderly. Aspirin for reducing events in the elderly (ASPREE)Drugs Aging20032089790314565783

- NewtonJLAllenAWestleyBRThe human trefoil peptide, TFF1, is present in different molecular forms that are intimately associated with mucus in normal stomachGut2000463122010673290

- NewtonJLJordanNPearsonJThe adherent gastric antral and duodenal mucus layer thins with advancing age in subjects infected with Helicobacter pyloriGerontology200046153710754373

- NgFHWongBCYWongSYClopridogrel plus omeprazole compared with aspirin plus omeprazole for aspirin-induced symptomatic peptic ulcers/ erosions with low to moderate bleeding/re-bleeding risk – a single-blind, randomised controlled studyAliment Pharmacol Ther2004193596514984383

- NgTMFoackKMKhorJLNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Helicobacter pylori and bleeding gastric ulcerAliment Pharmacol Ther200014203910651661

- NICENICE dyspepsia guidelines in primary care. [online]2005 Accessed 19 Aug 2005. URL: http://www.nice.org.uk/pdf/CG017NICEguideline.pdf

- NivYBattlerAAbuksisGEndoscopy in asymptomatic minidose aspirin consumersDig Dis Sci200550788015712641

- PilottoAFranceschiMLeandroGThe risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in elderly users of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: the role of gastroprotective drugsAging Clin Exp Res200315494914959953

- PilottoAFranceschiMLeandroGProton pump inhibitors reduce the risk of uncomplicated peptic ulcer in elderly either acute or chronic users of aspirin/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsAliment Pharmacol Ther2004201091715569111

- SababiMNilssonEHolmLMucus and alkali secretion in the rat duodenum: effects of indomethacin, N-nitro-L-arginine and luminal acidGastroenterology19951091526347557135

- SeinelaLAhvenainenJPeptic ulcer in the very old patientsGerontology200046271510965183

- SempleJINewtonJLWestleyBRDramatic diurnal variation in the concentration of the human trefoil peptide TFF2 in gastric juiceGut2001486485511302963

- SerranoPLanasAArroyoMTRisk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking low-dose aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular diseasesAliment Pharmacol Ther20021619455312390104

- SmithWLDeWittDLGaravitoRMCyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biologyAnnu Rev Biochem2000691458210966456

- SolomonDHGurwtizJHToxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the elderly: is advanced age a risk factor?Am J Med1997102208159217572

- SommervilleKFaulknerGLangmanMJSNonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and bleeding peptic ulcerLancet1986146452869208

- SpychalRTGogginPMMarrerJMSurface hydrophobicity of gastric mucosa in peptic ulcer disease-relationship to gastritis and campylobacter pylori infectionGastroenterology199098125042323518

- StackWAAthertonJCHawkeyGMInteractions between Helicobacter pylori and other risk factors for peptic ulcer bleedingAliment Pharmacol Ther20021649750611876703

- TahaASAngersonWNakshabendiIGastric and duodenal mucosal blood flow in patients receiving non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs – influence of age, smoking, ulceration and Helicobacter pyloriAliment Pharmacol Ther199374158439636

- TrinderPRajaratnamGLewisMProphylactive aspirin use in the adult general populationJ Public Health Med2003253778014747600

- WallaceJLMcKnightWDel SoldataPAntithrombotic effects of nitric-oxide releasing gastric sparing aspirin derivativeJ Clin Invest1995962711188675638

- VoutilainenMMantynenTFarkkilaMImpact of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug and aspirin use on the prevalence of dyspepsia and uncomplicated peptic ulcer diseaseScand J Gastroenterol2001368172111495076