Abstract

This study notes the differences between trust and distrust perceptions by the elderly as compared with younger populations. Given the importance of trust and distrust in compliance, changing behaviors, and forming partnerships for both health and disease management, it is necessary to be able to measure patient–doctor trust and distrust (PDTD). Following recent conceptualizations on trust and distrust as coexistent states, this study hypothesizes predictors of PDTD. We are proposing that these predictors form the basis for designing, developing and validating a PDTD scale (PDTDS). It is important to capture the trust–distrust perceptions of older patients as they confront the complexities and vulnerabilities of the modern healthcare delivery system. This is necessary if we are to design interventions to change behaviors of both the healthcare provider and the older patient.

Keywords:

Introduction

Trust in the doctor and the healthcare system is important for patient satisfaction, compliance and partnership towards successful aging and better disease management. CitationWilliams (2001) defined trust as “one’s willingness to rely on another’s actions in a situation involving the risk of opportunism.” Recent work on trust has increasingly focused on conceptualizations regarding distrust (CitationSitkin and Ross 1993; CitationBies and Tripp 1996; CitationSitkin and Stickel 1996). Distrust entails “the belief that a person’s values or motives will lead one to approach all situations in an unacceptable way” (CitationSitkin and Ross 1993). Distrust is not mistrust or no-trust, the contradictory notion of trust. Distrust is a qualified conditional trust in doctors and/or the healthcare delivery system on the part of the patient. The latter may be burdened by cost, beset by anxiety, having to cope with difficulties of navigating the managed care system, and confused by the complexities of modern medicine. In the midst of such a multifaceted healthcare delivery system, positive and legitimate distrust can co-exist with positive trust during patient–physician encounters. This area of positive distrust has received minimal attention in the medical literature (CitationMcGary 1999; CitationGoold 2002; CitationRose et al 2004), when compared with the numerous studies relating to patient–physician trust (CitationThom and Campbell 1997; CitationKao, Green, David, et al 1998; CitationKao, Green, Zaslavsky, et al 1998; CitationSafran et al 1998; CitationThom et al 1999; CitationLeisen and Hyman 2001; CitationThom 2001; CitationHall et al 2002), that followed the sentinel work of CitationAnderson and Dedrick’s (1990) patient–physician trust scale. When it comes to the elderly, however, there appears to be a paucity of research on trust or distrust (CitationMontgomery et al 2004; CitationMoreno-John et al 2004; CitationTrachtenberg et al 2005), despite the fact that the elderly account for over 30% in medical resource utilization as a group in the US. Moreover, with increasing longevity and the growing numbers of the elderly worldwide, the issue of patient–doctor trust and distrust (PDTD) in this group of patients clearly merits research. In this exploratory study we will focus on the concept of trust and distrust as perceived by a convenient sample of older patients with chronic diseases who had interacted with their doctors and healthcare delivery systems over a long period of time. We will then review the literature as it relates to the dynamics of trust–distrust in the day-to-day patient–doctor encounter and define a set of hypothesized predictors of PDTD. We hope these predictors will serve as a basis to develop a PDTD scale (PDTDS).

Importance of patient trust–distrust determinants

It is important to understand the concept of PDTD. We would therefore like to expound on the trust–distrust concept based on various theories of trust and distrust and accordingly, derive hypothesized predictors of trust–distrust. Traditionally, patients have relied on trust in medical professionals to minimize the stress and uncertainty associated with their illness. If in addition, patients have to worry about their physician’s control, given the increasing strictures of managed care and the perceptions related to the trustworthiness of the Health Maintenance Organization (HMO), it may become a major factor in how patients trust their physicians (CitationGray 1997). In the last four to five years, state regulators have reported a 50% rise in complaints about HMOs by patients and physicians, particularly regarding healthcare service denials or delays, and most of these complaints reflect the public’s increasing distrust of managed care rather than a true decline in quality healthcare (CitationMechanic and Rosenthal 1999). Obviously, increasing trust of patients in the entire healthcare delivery system, inclusive of managed care, is critical.

This trust–distrust bi-dimensional but mutually complementing perspective may provide a better and more insightful framework to understand the dynamics of patient–doctor trust-relations than those expressed in existing trust scales (CitationAnderson and Dedrick 1990; CitationThom and Campbell 1997; CitationSafran et al 1998; CitationLeisen and Hyman 2001; CitationThom 2001; CitationHall et al 2002). Distrust is not mistrust, nor the opposite of trust, but a complimentary dimension that can enable doctors, nurses, managed care executives, and even governments who subsidize healthcare, to understand the specific and even positive role of distrust in patient–doctor trust. High levels of patient–doctor trust can coexist with high levels of patient–doctor distrust. Given the current complex US healthcare delivery system, patients are bound to experience high levels of trust and distrust with healthcare providers. Moreover, the perceived complexity, ambiguity, and vulnerability of healthcare delivery inputs, its processes and outcomes, and patient–physician encounters are bound to be a mix of high trust and distrust states that need to be carefully studied, predicted, and managed.

Measuring PDTD in older populations is important, especially, to better understand patient perceptions and design interventions to influence both doctor and patient behaviors. In chronic disease management, trust and distrust are important if patients are to adhere to care plans in partnership with their doctors.

Methodology

As an initial and experimental approach to the understanding of patient trust–distrust in doctors, we analyzed the results from an earlier study of patient trust in doctors where distrust was only a component of a scale that measured patient trust and satisfaction with doctors. This scale was administered to a convenient sample of 515 patients with chronic diseases. The scale (see ) was designed to assess four major trust factors: Trust 1 (cooperation and caring attributes by doctors); Trust 2 (quality and hospital reputation); Trust 3 (patient’s confidence in doctors); and Trust 4 (patient’s distrust and fear in the healthcare delivery system).

Based on these preliminary results we undertook to investigate in depth the trust–distrust literature both in the management and the medical sociology fields and accordingly, derive a set of hypothesized predictors which we believe can be used as the basis for developing a PDTDS.

Results

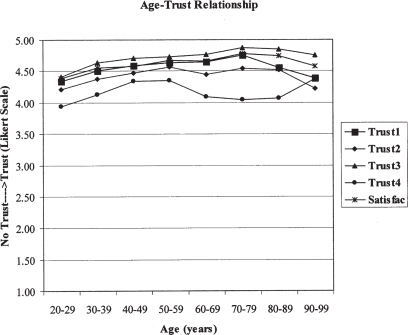

Our preliminary study involved a mixed population of 200 breast cancer survivors, 174 hospitalized patients, and 141 ambulatory care patients. The demographics of the study population are presented in . We then compared the age–trust relationship and patient satisfaction (). As observed in , whereas the first three constructs of the trust instrument (Trust 1, Trust 2, and Trust 3) moved in tandem with patient satisfaction, the fourth component that measured trust–distrust (Trust 4) significantly departed from the other three trust components and the satisfaction construct. Additionally, when the patient data was classified into age-groups, elderly (aged 65 years and above) and younger (aged less than 65), there were significant differences (p=0.005) in trust and distrust levels between the elderly and younger patients (). To further investigate and analyze this phenomenon, we chose the first sample of 200 female breast-cancer patients. In this sample, we studied two major groups: 101 African-American and 69 Caucasian patients. These results are provided in . As observed in , while the first trust components are statistically equivalent across both groups, the fourth component of trust–distrust shows significantly (p=0.028) higher levels of distrust among African-American patients. These results caused us to study the conceptual and theoretical foundations of patient trust–distrust and their determinants.

Figure 1 The relationship between age, trust (Trust 1 – cooperation, caring, and vulnerability; Trust 2 – quality and hospital reputation; Trust 3 – confidence; Trust 4 – distrust and fear) and patient satisfaction.

Table 1 Sample sociodemographics

Table 2 Comparison between trust and satisfaction among elderly (age ≥65 years) and younger (age <65 years) groups

Table 3 Characteristics of the female breast cancer patients (Study 1: n=170)

Conceptual and theoretical foundations of patient trust–distrust in doctors

While there is widespread agreement on the importance of trust–distrust in human conduct, there also appears a bewildering diversity in defining the construct of trust (CitationHosmer 1995). Trust researchers have developed different trust constructs in response to disparate sets of questions regarding social phenomena (CitationBigley and Pearce 1998). There has been remarkably little effort, however, to integrate these different perspectives (CitationLewicki and Bunker 1996; CitationBigley and Pearce 1998). The formidable variety in approaches to trust is largely a function of the diverse theoretical perspectives and research interests of scholars engaged in trust research (CitationLewicki and Bunker 1996). For instance, personality theorists view trust as an individual attribute or difference; sociologists and economists study trust as an institutional phenomenon or arrangement, and social psychologists conceptualize trust as behavior in a situational context: eg, an expectation of another party in a transaction (CitationSitkin and Ross 1993; CitationLewicki and Bunker 1996). Whereas earlier trust literature in the management field contrasts trust with distrust as polar opposites, later developments reveal a complimentary approach to trust and distrust. Trust and distrust are separate dimensions that can coexist and mutually reinforce each other. It is therefore necessary to review these two streams of literature for a better understanding of the concepts of trust and distrust. summarizes the discussions to follow.

Table 4 A synthesis of theories and definitions of trust and distrust

Trust and distrust as polar opposites

Psychological view of trust and distrust

The earliest views on trust reflect a psychological approach. CitationMellinger (1956) defined trust as an individual’s confidence in another person’s intentions and motives, and the sincerity of that person’s word. Following this approach, CitationRead (1962) argued that trusting individuals: (a) expect their interests to be protected and promoted by those they trust; (b) feel confident about disclosing negative personal information about themselves; (c) feel assured of full and frank information sharing; and (d) are prepared to overlook apparent breaches of trust relationship. CitationDeutsch (1960) viewed trust as an individual’s confidence in the intentions and capabilities of the trust partner and the belief that he or she would behave as hoped. CitationDeutsch (1960) also viewed distrust as confidence about a relationship partner’s undesirable behavior, stemming from the knowledge of his or her capabilities and intentions. Our first research hypothesis in this regard is:

Hypothesis 1: The higher the patients’ sense that their interests are not being protected or promoted by doctors and nurses, the higher their distrust is with doctors and other healthcare providers.

Behavior theory of trust and distrust

Examining trust and distrust from a rational (predictive) choice perspective, behavior decision theorists define trust as co-operative conduct and distrust as nonco-operative conduct in a mixed-motive game situation, and see trust and distrust as polar opposites (CitationColeman 1990). Some earlier social psychological studies also considered trust and distrust as conflicting psychological states, and hence as unstable and transitory, and reckoned trust and distrust as opposing attributes (CitationLewis and Weigert 1985). Normatively, therefore, trust was viewed as something good, and distrust as something bad or as a psychological disorder. Distrust was considered to reflect psychological imbalance and inconsistency, both adverse conditions that must be avoided (CitationDeutsch 1960). Our second research hypothesis in this regard is:

Hypothesis 2: The higher the patients’ sense of nonco-operative conduct and conflicting interests on the part of doctors and nurses, the higher their distrust is with doctors and other healthcare providers.

Personality dispositional view of trust and distrust

For personality researchers who view trust as an individual difference, trust and distrust exist at opposite ends of a single trust–distrust continuum (CitationRotter 1971). They are mutually exclusive and opposite conditions. In general, low trust expectations are indicative of high distrust from this point of view (CitationStack 1978; CitationTardy 1988). The central focus of these theories is how individuals develop their propensities to trust, and how these predilections affect their thoughts and actions regarding persons (CitationRotter 1967, Citation1971, Citation1980). According to these theories, factors exist within individuals that predispose them to trust or distrust others, especially when they do not know them. CitationRotter (1967, Citation1971, Citation1980) argues that trust is a stable belief based on individuals’ extrapolations from their early life-experiences. Trust develops during childhood as an infant seeks and receives help from its benevolent caregiver. Children of trusting parents trust others more easily than children of distrusting parents, and children with trusting siblings are better predisposed to trust. The more novel, complex, and unfamiliar the situations, the more influence such predispositions bear on trusting (or distrusting) behavior. According to CitationHardin 1998. people with trusting dispositions co-operate better, whereas people with distrusting predispositions tend to avoid co-operative activities, fearing exploitations. The latter, have fewer positive interaction experiences that beget trust; the former have more and progressively increase their trust. In this sense, trust begets trust, and distrust perpetuates distrusting predilections.

Cognition-based trust researchers, however, would argue that trust relies on rapid, cognitive cues or first impressions, as opposed to personal dispositional characteristics of trust (CitationLewis and Weigert 1985; CitationMeyerson et al 1996). Especially, during first new patient–doctor encounters, parties may have to develop trust based on initial cognitive cues and first impressions. In such situations, individuals may have to rely either on one’s predispositions to trust or on institution-based trust-development cues. Our third research hypothesis in this regard is:

Hypothesis 3: The higher the patients’ predispositions to distrust the complex, unfamiliar, and costly healthcare system, the higher their distrust is with doctors and other healthcare providers.

Expectation theory of trust and distrust

Expectation theory defines trust as “a generalized expectancy held by an individual that the word, promise, oral or written statement of another individual or group can be relied upon” (CitationRotter 1980). Trust is “a set of expectations shared by all those involved in an exchange” (CitationZucker 1986). Trust is based on an individual’s expectations that others will behave in ways that are helpful or at least not harmful (CitationGambetta 1988). CitationZucker’s (1986) definition of trust as a preconscious expectation suggests that vulnerability is only salient to trustors after a trustee has caused them harm. In reciprocal terms, distrust is understood as the expectation that others will not act in one’s best interests, even engaging in potentially harmful behavior (CitationGovier 1994). Our fourth research hypothesis in this regard is:

Hypothesis 4: The higher are the patients’ expectations regarding doctors, nurses, hospitals and managed healthcare, the higher their distrust is with doctors and other healthcare providers.

Criticism of trust and distrust as polar opposites

Research within management literature has focused on trust primarily in terms of “rational prediction” (CitationLewis and Weigert 1985) wherein agents conceive distrust as a highly risky situation that must be reduced or avoided by rational choices that predict distrust. Such “predictive” accounts of trust “appear to eliminate what they say they describe”, thus disregarding or removing core elements of trust (CitationLewis and Weigert 1985). Under this view, trust exists only in an uncertain and risky environment; that is, trust cannot exist in an environment of certainty (CitationBhattacharya et al 1998).

The expectation-approach views trust as a disposition that would be most predictive in situations where individuals are relatively unfamiliar with one another. Trust, in this tradition, is viewed as a calculated decision to cooperate with specific others, based on information about others’ personal qualities and social constraints: a context that very much reflects the patient–doctor trust encounter situation. Under this view, trust reflects an aspect of predictability, that is, it is an expectation; it cannot exist without some possibility of error. That is, trust can exist with some distrust. For instance, when patients say they trust a doctor, they do not necessarily make a statement whether the doctor is good or bad; but they reflect the notion of trust as a prediction of the doctor’s behavior in a given context (CitationBhattacharya et al 1998).

summarizes various polar theories of trust and distrust. Key assumptions of these theories are: (a) trust and distrust are mutually exclusive and opposite unidimensional conditions; that is, trust and distrust are polar opposites; (b) trust is good and distrust is bad; (c) the social context of trust and distrust is either irrelevant or of low consequence (CitationLewicki et al 1998). Most of these models are “undersocialized” and omit the role of concrete personal and social relationships and structures of such relations.

The major problem for these divergent views on trust and distrust is that scholars (a) have given limited attention to the role of social context in trust and distrust research, and (b) have considered trust–distrust as a one-dimensional construct. In the latter case, scholars have considered interpersonal relationships within organization or exchange situations as one-dimensional, with a single dimension or component of relationship to determine the quality of the entire relationship (CitationLewicki et al 1998).

Trust and distrust as complimentary constructs

Trust and distrust are reciprocal terms. Both trust and distrust are separate but linked dimensions. They are not polar opposites on a single continuum such that low trust means high distrust and high trust means low distrust. Trust and distrust both entail certain expectations, but whereas trust expectations anticipate beneficial conduct from others, distrust expectations anticipate injurious conduct (CitationLewicki et al 1998). Both involve movements toward certainty: trust concerning expectations of things hoped for and distrust concerning expectations of things feared. Hence, both states can coexist (CitationPriester and Petty 1996); they are functional equivalents (CitationLuhmann 1990).

Organizational psychology theory of trust and distrust

Institution-based trust means that one believes the necessary impersonal structures are in place to enable one to act in anticipation of a successful future endeavor (CitationZucker 1986; CitationShapiro 1987). CitationZucker (1986) describes how certain specific institutional or social structures and arrangements generate trust. Institution-based distrust means that one believes the necessary impersonal structures are not in place. For instance, rational bureaucratic organizational forms could be trust-producing mechanisms for situations where the scale and scope of economic activity overwhelm interpersonal trust relations. Public auditing of firms, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulations, Federal Trade Commission (FTC) mandates and other government vigilance programs may increase customer trust in those companies. Institution-based trust researchers maintain that trust reflects the security one feels about a situation because of guarantees, safety nets, or other structures (CitationZucker 1986; CitationShapiro 1987). Thus, the safe and structured atmosphere of a classroom may enable students to develop high levels of initial trust (CitationLewis and Weigert 1985; CitationShapiro 1987). Tough screening and high professional experience levels of new recruits may help senior employees to trust then implicitly.

Trusting intention at the beginning of a relationship may be high because of institution-based trust stimulators. Institution-based trust literature speaks of two such stimulators: situation normality and structural assurances. Situation-normality: defined as the belief that successful interaction is likely because the situation is normal (CitationGarfinkel 1963) or customary (CitationBaier 1986), or that everything is in proper order (CitationLewis and Weigert 1985). Structural assurances: defined as the socially learned belief that successful interaction is likely because of such structural safeguards or contextual conditions as promises, contracts, regulations, legal recourse, and guarantees are in place. The current healthcare crisis as a result of lack of insurance, high prices of prescription drugs in the US and fragmentation of care are instances of breakdown of situation normality and structural assurances such that high levels of trust and distrust could coexist. A fifth researchable hypothesis in this regard is:

Hypothesis 5: The higher the patients’ sense of situation abnormality and lack of structural assurances in modern health delivery system, the higher their distrust is with doctors and other healthcare providers.

Sociological theory of trust and distrust

Sociologists recognize the importance of trust and distrust as mechanisms for reducing social complexity and uncertainty, and, accordingly, view them as functional equivalents or substitutes. CitationLuhmann (1990) argues that both trust and distrust function to allow rational actors to understand, contain, and manage social uncertainty and complexity, but they do so by different means. Trust reduces social complexity and uncertainty by disallowing undesirable conduct from consideration and replacing it with desirable conduct. Conversely, distrust functions to reduce social complexity and uncertainty by allowing undesirable conduct and by disallowing desirable conduct in considering alternatives in a given situation. In the latter case, distrust becomes a “positive expectation of injurious action” (CitationLuhmann 1990). Distrust simplifies the social world, allowing the individual to move rationally to take protective action based on these positive expectations of harm. Social structures appear most stable where there is a healthy dose of both trust and distrust to generate a productive tension of confidence (CitationLewicki et al 1998). CitationLuhmann (1990) even argues that “trust cannot exist apart from distrust, and trust cannot increase without increases in distrust. Increases in trust or distrust – apart from increases in the other – may do more harm than good.” An over-trusted person can often exploit the over-trusting person. “Apart from a genuine openness to the possible necessity of distrust, benign and unconditional trust appears to be an extremely dangerous strategy for managing social relations” (CitationLewicki et al 1998). Our sixth research hypothesis in this connection is:

Hypothesis 6: The higher the patients’ sense of social complexity and uncertainty brought about by undesirable behaviors of doctors, managed healthcare and other healthcare providers, the higher their distrust is with doctors and other healthcare providers.

Social psychology theory of trust and distrust

Human psychology functions in a social context. Hence, if the social context of an exchange situation or an organizational relationship is properly focused and fully brought into the social equation, then it is quite possible that an individual who trusts a partner on some attributes (eg, scientific knowledge, technical skill) may distrust that partner on other features (eg, social skills, ethical conduct, compassion skills), and both these states can coexist. According to social psychologists (CitationCacioppo et al 1997), positive-valent and negative-valent attitudes can coexist, and thus, trust which involves confident positive expectations and distrust which implies confident negative expectations regarding trusting partners, can operate simultaneously in the same individual, although from different viewpoints (CitationLewicki et al 1998).

CitationWatson and Tellegen (1985) noted that high positive affectivity (eg, active, strong, excited, enthusiastic, and elated) was not synonymous with low negative affectivity (eg, calm, relaxed, and placid). Similarly, low positive affectivity (eg, sleepy, dull, drowsy, and sluggish) was not synonymous with high negative affectivity (eg, distressed, scornful, hostile, fearful, nervous, and jittery). These and other studies (CitationCacioppo and Gardner 1993) clearly indicate that positive-valent and negative-valent constructs are separable. The two constructs may systematically and negatively correlate, but their antecedents and consequences may be separate and distinct (CitationCacioppo and Gardner 1993). The factors related to positive affect are distinct from those surrounding negative affect (CitationWatson and Tellegen 1985). These considerations indicate that the bases of trust and distrust may be different and separable. That is, trust is not the opposite of distrust; there may not be a singular trust–distrust continuum. High trust may be opposed to low trust; and high distrust may be antithetical to low distrust. The two states, even though ambivalent, could coexist. Our seventh research hypothesis may be stated as follows:

Hypothesis 7: The higher the patients’ level of negative-valent attitudes regarding doctors, nurses, hospitals, and managed healthcare, the higher their distrust is with doctors and other healthcare providers.

Interdependence theory of trust and distrust

Recent definitions of trust imply interdependent behavioral expectations. Thus, CitationHosmer (1995) defines trust as one party’s optimistic expectations of the behavior of another, when the party must make a decision about how to act under conditions of vulnerability and dependence. According to CitationMoorman and colleagues (1992) and CitationMishra (1996), vulnerability is an important constituent of trust. That is, in the absence of risk or vulnerability trust is not necessary, since outcomes are not of consequence to trustors. Sabel’s definition of trust assumes vulnerability: “trust is the mutual confidence that no party to an exchange will exploit the other’s vulnerability” (CitationSabel 1993). According to CitationMayer and colleagues (1995), vulnerability accompanies trust. They define trust as “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control the other party.” CitationZucker’s (1986) definition of trust as a preconscious expectation suggests that vulnerability is only salient to trustors after a trustee has caused them harm. Following this important trend, we will incorporate the domain of vulnerability in the trust–distrust scale, since so much of modern medicine in all its complexity, speed on innovation, and cost-conscious managed care involves vulnerability. CitationWilliams (2001) defines trust as “one’s willingness to rely on another’s actions in a situation involving the risk of opportunism.” In contrast, distrust entails “the belief that a person’s values or motives will lead one to approach all situations in an unacceptable way” (CitationSitkin and Ross 1993).

In fact, trust-research “appears to be premised on the general idea that actors (ie, individuals, groups or organizations) become, in some ways, vulnerable to one another as they interact in social situations, relationships and systems” (CitationBigley and Pearce 1998). As organizational arrangements become more complex (as in the current healthcare environment), actors’ vulnerability to one another could become broader and deeper, and trust may be one of the best mechanisms actors have to cope with these new conditions (CitationBigley and Pearce 1998). Often, patients are unfamiliar with physicians, surgeons, nurses, and hospitals. Gathered information in this regard may not be complete or totally reliable for establishing affective bonds with one another. Patient trust may be an effective surrogate in this regard. Our eighth related research hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 8: The higher the patient’s sense of unfamiliarity and vulnerability with the complexity of modern health delivery system, the higher their dependence upon and distrust with doctors and other healthcare providers.

Complimentary theories of trust and distrust

summarizes various complimentary theories of trust and distrust. They make some key assumptions: (a) Trust and distrust are mutually inclusive and complementary bi-dimensional conditions; that is, trust and distrust can coexist and reinforce each other; (b) Trust is good and positive and distrust is also good and positive, although based on different expectations; trust relates to beneficial expectations; distrust involves hazardous expectations; life experiences involves both, and often at the same time; (c) Trust–distrust is embedded in the complex, unfamiliar, and vulnerable social context of human relationships.

Discussion

The importance of PDTD cannot be underestimated as it relates to compliance and patient satisfaction. There have been recent changes in the experiences of Medicare beneficiaries as a result of decline in the quality of interactions between patients and their doctors, a breakdown in continuity and integration of care and difficulties with access to care despite improvements in medical technology (CitationMontgomery et al 2004).

Expectations of care by the elderly include trust and the need for a sense of personal touch. Trust is complex in the older person given that they could be satisfied but not trust providers or they could trust providers but not be satisfied (CitationHupcey et al 2004). A recent study on how patients’ trust relates to their involvement in medical care (CitationTrachtenberg et al 2005) identifies age as an important predictor with older patients being more compliant, deferential, passive, and trusting of their doctors as compared with younger patients. Our preliminary studies and those of other research workers appears to support that the perceptions of PDTD in the elderly are different from the rest of the patient population. It is therefore necessary to have an ability to measure PDTD as a basis for developing interventions that can positively affect both patient and doctor behaviors during the clinical encounter. We are proposing a set of eight hypothesized predictors, based on the trust distrust theories that could serve as a basis for developing a PDTD scale.

synthesizes patient–physician interpersonal relations as a function of Low versus High, Trust and Distrust. Each quadrant suggests clear implications to physicians, doctors and other healthcare givers, as well as to patients. It is a challenge for all healthcare givers to generate in their patients lower levels of fear, skepticism, and cynicism such that costs of patient monitoring and fragmentation of care is significantly reduced. Analogously, healthcare providers must do everything within their power and skills to generate in their patients high levels of hope, faith, confidence, assurance, and also welcome high patient cooperation.

Table 5 Patient–physician interpersonal relations as a function of low and high, trust and distrust

Based on the trust–distrust literature reviewed earlier and the various factors of trust–distrust hypothesized, we present a tentative patient’s trust–distrust measurement instrument in . Accordingly, indicates which theory reflects which scale statement. Following , projects which statement is best positioned to fall into one of the four quadrants. Both and ensure nomological (conceptual–theoretical) validity of the trust–distrust scale. Finally, sketches costs versus benefits of various patient–physician trust–distrust encounters. The bottom line in healthcare is to have a profit margin so that ongoing research education and development of innovative modes of healthcare is possible.

Table 6 Patient–physician trust–distrust scale statements

Table 7 Distribution of trust–distrust scale statement by theories of trust–distrust

Table 8 Distribution of scale statement in the trust–distrust quadrants

Table 9 Profile of patient–physician trust levels: costs versus benefits

Concluding remarks

Distrust of doctors and the healthcare system may be a significant barrier to seeking proper medical care, enforcing effective preventive care and following treatment regimens. Hence, conceiving, formulating, and implementing various strategies to reduce patient distrust and mistrust are an important component of delivering modern healthcare.

Disclosure

To the best of our knowledge, there exists no known conflict of interest among the authors.

References

- AndersonLADedrickRF1990Development in the Trust in Physician scale: a measure to assess interpersonal trust in patient–physician relationshipsPsychol Rep6710911002084735

- BaierA1986Trust and antitrustEthics9623160

- BhattacharyaRDevinneyTMPillutlaMM1998A formal model of trust based on outcomesAcad Manage Rev2345972

- BiesRJTrippTM1996Beyond distrust: “getting even” and the need for revengeKramerRMTylerTRTrust in organizations: frontiers of theory and researchThousand Oaks, CASage24660

- BigleyGAPearceJL1998Straining for shared meaning in organization science: problems of trust and distrustAcad Manage Rev2340521

- CacioppoJTGardnerWL1993What underlies medical donor attitudes and behavior?Health Psychol12269718404799

- CacioppoJTGardnerWLBerntsonGG1997Beyond bipolar conceptualizations and measures: the case of attitudes and evaluative spacePerson Soc Psychol Rev1325

- ColemanJS1990The foundations of social theoryHarvardBelknap

- DeutschM1960The effect of motivational orientation upon trust and suspicionHuman Rel1312339

- GambettaD1988Can we trust TrustGambettaDTrust: making and breaking cooperative relationsNew York, NYBasil Blackwell21338

- GarfinkelH1963A conception and experimentation with “trust” as a condition of stable concerted actionsHarveyOJMotivations and social interactionsNew York, NYRonald Pr187238

- GooldSD2002Trust, distrust and trustworthinessJ Gen Intern Med17798111903779

- GovierT1994Is it a jungle out there? Trust, distrust, and the construction of social realityDialogue2516178

- GrayBH1997Trust and trustworthy care in the managed care eraHealth Affairs1634499018941

- HallMAZhengBDuganE2002Measuring patients’ trust in their primary care providersMed Care Res Rev5929331812205830

- HardinJW1998An in-depth look at congressional committee jurisdictions surrounding health issuesJ Health Polit Policy Law23517509626643

- HosmerLT1995Trust: the connecting link between organization theory and philosophical ethicsAcad Manage Rev20379403

- HupceyJEClarkMBHutchesonCR2004Expectations for care: older adults’ satisfaction with and trust in healthcare providersJ Gerontol Nurs30374515575190

- KaoACGreenDCDavidNA1998Patient’s trust in their physicians: effects of choice, continuity, and payment methodJ Gen Intern Med1368169798815

- KaoACGreenDCZaslavskyAM1998The relationship between method of physician payment and patient trustJAMA2801708149832007

- LeisenBHymanMR2001An improved scale for assessing patients’ trust in their physicianHealth Market Q192342

- LewickiRJBunkerBB1996Developing and maintaining trust in work relationshipsKraemerRMTylerTRTrust in organizations: frontiers of theory and researchThousand Oaks, CASage11439

- LewickiRJMcAllisterDJBiesRJ1998Trust and distrust: new relationships and realitiesAcad Manage Rev2343858

- LewisJDWeigertAJ1985Trust as a social realitySoc Forces6396785

- LuhmannN1990Familiarity, confidence, trust: problems and alternativesGambettaDTrustLondonBlackwell94107

- MayerRCDavisJHSchoormanDF1995An integrated model of organizational trustAcad Manage Rev2070934

- McGaryH1999Distrust, social justice, and healthcareMt Sinai J Med662364010477475

- MechanicDRosenthalM1999Responses of HMO medical directors to trust building in managed careMilbank Q77310197026

- MellingerGD1956Interpersonal trust as a factor in communicationJ Abnorm Psychol523040913318834

- MeyersonDWeickKEKramerRM1996Swift trust and temporary groupsKramerRMTylerTRTrust in organizations: frontiers of theory and researchThousand Oaks, CASage16695

- MishraAK1996Organisational responses to crisis: the centrality of trustKramerRMTylerTRTrust in organizations: frontiers of theory and researchThousand Oaks, CASage

- MontgomeryJEIrishJTWilsonIB2004Primary care experiences of Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–2000J Gen Intern Med19991815482550

- MoormanCZaltmanGDeshpandeR1992Relationships between providers and users of marketing research: the dynamics of trust within and between organizationsJ Market Res2931428

- Moreno-JohnGGachieAFlemingCM2004Ethnic minority older adults participating in clinical research: developing trustJ Aging Health165 Suppl93S123S15448289

- PriesterJRPettyRE1996The gradual threshold model of ambivalence: relating the positive and negative bases of attitudes to subjective ambivalenceJ Personal Soc Psychol7143149

- ReadWH1962Upward communications in industrial hierarchiesHuman Rel15315

- RoseAPetersNSheaJA2004Development and testing of the healthcare system distrust scaleJ Gen Intern Med19576314748861

- RotterJB1967A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust, J Personal3565165

- RotterJB1971Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trustAm Psychol2644352

- RotterJB1980Interpersonal trust, trustworthiness, and gullibilityAm Psychol3517

- SabelCF1993Studied trust: Building new forms of cooperation in a volatile economyAm Psychol3517

- SafranDKosinkiMTarlovAR1998The primary care assessment survey: tests of data quality and measurement performanceMed Care36728399596063

- ShapiroSP1987The social control of interpersonal trustAm J Sociol9362358

- SitkinSBRossNL1993Explaining the limited selectiveness of legalistic “remedies” for trust/distrustOrgan Sci436781

- SitkinSBStickelD1996The road to hell: the dynamics of distrust in an era of qualityKramerRMTylerTRTrust in organizations: frontiers of theory and researchThousand Oaks, CASage196215

- StackL1978TrustLondonHExnerJDimensions of personalityLondonJohn Wiley & Sons56199

- TardyCH1988Interpersonal evaluations: measuring attraction and trustTardyCHA handbook for the study of human communicationNorwood, NJAblex26983

- TrachtenbergFDuganEHallMA2005How patients’ trust relates to their involvement in medical careJ Fam Pract543445215833226

- ThomDH2001Physician behaviors that predict patient trustJ Fam Pract50323811300984

- ThomDHCampbellB1997Patient–physician trust: an exploratory studyJ Fam Pract44169769040520

- ThomDHRibisiKMStewardAL1999Validation of a measure of patients’ trust in their physician: the trust in physician scaleMed Care375101710335753

- WatsonDTellegenA1985Toward a consensual structure of moodPsychol Bull982192353901060

- WilliamsM2001In whom we trust: group membership as an affective context for trust developmentAcad Manage Rev2637796

- ZuckerLG1986Production of trust: institutional sources of economic structure, 1840–1920StrawBMCummingsLLResearch in organizational behavior8Greenwich, CTJAI Pr53111