Abstract

Physical exercise is proposed as a highly effective means of treating and preventing the main causes of morbidity and mortality – most of which are associated with aging – in industrialized countries. Low physical fitness is an important risk factor for cardiovascular and all-causes morbidity and mortality; indeed, it is even a predictor of these problems. When properly measured, the assessment of physical fitness can be a highly valuable indicator of health and life expectancy and, therefore, should be performed routinely in the clinical setting. Individually adapted training programs could be prescribed based on fitness assessment results and an adequate knowledge of patient lifestyle and daily physical activity. Such training programs would allow people to develop their maximum physical potential, improve their physical and mental health, and attenuate the negative consequences of aging.

Introduction

The increase in life expectancy and the reduction in the birth rate are major problems faced by industrialized societies. From a health and social point of view, it is more important that research be orientated towards promoting healthier aging than simply finding better ways to treat aging-related illnesses (CitationAbbott 2004). A highly effective form of promoting healthy aging is the practice of physical exercise with the aim of improving physical fitness. Several studies have clearly shown that physical fitness is an important predictor of both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. In addition it is a good predictor of being able to live an independent life at old age (CitationMyers et al 2002; CitationMyers 2003; CitationGulati et al 2003; CitationKurl et al 2003; CitationPiepoli et al 2004). This work discusses the importance of physical fitness as an index of health, the relationship between physical fitness and aging, how to assess physical fitness in a clinical setting, and the prescription of exercise for improving physical fitness and, consequently, positively influencing the aging process.

Physical exercise as an anti-aging intervention

Appropriately undertaken, physical exercise is the best means currently available for delaying and preventing the consequences of aging, and of improving health and wellbeing.

It is important to differentiate between three different but inter-related concepts: physical activity, physical exercise, and physical fitness. Physical activity refers to any body movement produced by muscle action that increases energy expenditure. Exercise refers to planned, structured, repetitive, and purposeful physical activity. Physical fitness is the capacity to perform physical exercise. Physical fitness makes reference to the full range of physical qualities, eg, aerobic capacity, strength, speed, agility, coordination, and flexibility. It can be understood as an integrated measurement of all the functions (skeletomuscular, cardiorespiratory, hematocirculatory, psychoneurological, and endocrine-metabolic) and structures involved in the performance of physical activity or physical exercise or both. Thus, being physically fit implies that the response of these functions and structures will be adequate. A person cannot be more physically fit than that allowed by the function or structure in poorest condition in their body.

Anti-aging-related physical fitness includes those components of physical fitness associated more with aspects of good health and/or disease prevention (Figure ).

The importance of physical fitness

The physical fitness of both men (CitationMyers et al 2002; CitationMyers 2003) and women (CitationGulati et al 2003) is an excellent predictor of life expectancy, both for those who are healthy (CitationKurl et al 2003) and for those who suffer some form of heart disease (CitationPiepoli et al 2004).

Over the last 15 years, numerous epidemiological and prospective studies have reported a strong association between physical fitness and the morbidity–mortality index of the population (CitationBalady 2002; CitationCarnethon et al 2003), even in overweight and obese persons (CitationBlair and Brodney 1999). Being physically fit drastically reduces all-cause mortality (CitationMyers 2003). Improving one’s physical fitness can reduce the risk of death by 44% (CitationBlair et al 1995). In addition, several studies have shown that improving physical fitness has a favorable influence on self image, self-esteem, and depression, as well as anxiety and panic syndromes (CitationKirkcaldy et al 2002; CitationStrawbridge et al 2002; CitationGoodwin 2003). It has even been reported that, while pharmacological anti-depression treatment may induce a more rapid initial response, the efficacy of exercise is the same at 16 weeks (CitationBlumenthal et al 1999) (Table ).

Table 1 Beneficial effects on health of practicing regular physical exercise

The aerobic capacity as an index of health

The aerobic capacity is one of the most important components of physical fitness. Maximum aerobic capacity is expressed in terms of maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max). The VO2max can be expressed with respect to subject weight (ml/kg/min), in absolute terms (L/min), or in metabolic equivalents (METs) (1 MET is the energy expenditure at rest [~3.5 ml/kg/min]). Thus, if a subject has a VO2max of 42 ml/kg/min, he also has an energy expenditure of 12 METS (ie, he is able to increase his resting energy expenditure 12-fold).

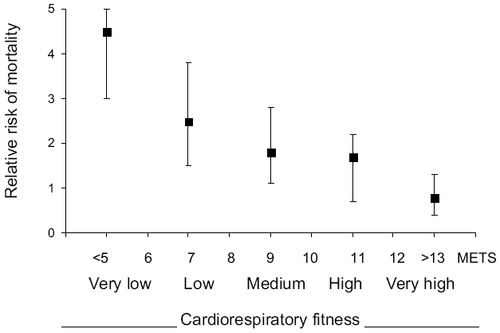

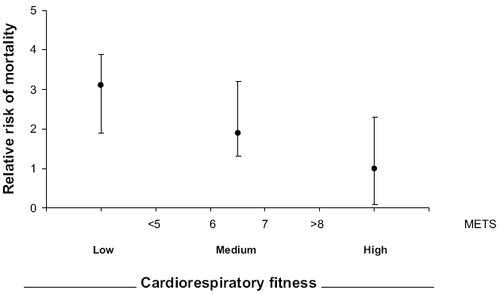

A number of important prospective studies have shown that the VO2max is the most important predictor of all-cause mortality, and in particular of cardiovascular death. This is true both for healthy persons and those with cardiovascular disease (CitationCarnethon et al 2003), and for both men (CitationLaukkanen et al 2001; CitationBalady 2002; CitationKurl et al 2003) and women (CitationGulati et al 2003; CitationMora et al 2003) of different ages (CitationMyers et al 2002). An almost linear reduction in mortality is seen as the aerobic capacity increases (CitationMyers et al 2002; CitationMora et al 2003) (, ). For each increase of 1 MET there is a 12% increase in the life expectancy of men (CitationMyers et al 2002) and a 17% increase in women (CitationGulati et al 2003; and , respectively). This is even more evident if cardiovascular mortality is considered alone, and is true for both men (CitationCarnethon et al 2003; CitationKurl et al 2003) and women (CitationGulati et al 2003; CitationMora et al 2003). An inverse relationship has also been found between aerobic capacity and mortality due to cancer – a relationship quite independent of age, alcohol intake, the suffering of diabetes mellitus, and even the use of tobacco (CitationLee and Blair 2002; CitationEvenson et al 2003; CitationLee et al 2003; Sawada, Muto, et al 2003). Similarly, it has been shown that the VO2max is an important determinant of insulin sensitivity (CitationSeibaek et al 2003; Sawada, CitationLee, et al 2003); low VO2max levels are associated with metabolic syndrome (abdominal obesity, glucose intolerance, type II diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance) (CitationBertoli et al 2003; CitationLakka et al 2003). A good aerobic capacity reduces the neuronal losses associated with aging (CitationColcombe et al 2003) and protects against cognitive dysfunction (CitationBarnes et al 2003).

Figure 2 The maximum aerobic capacity is a powerful predictor of all-cause mortality in men (drawn from data contained in CitationMyers et al 2002). The figure shows percentage survival as a function of the aerobic capacity (VO2max expressed in METs). Survival is worse in subjects with lower aerobic capacity.

Abbreviations: METs, metabolic equivalents; VO2max, maximum oxygen consumption.

Figure 3 The maximum aerobic capacity is a powerful predictor of all-cause mortality in women (drawn from data contained in CitationMora et al 2003). The figure shows percentage survival as a function of the aerobic capacity (VO2max expressed in METs). Survival is worse in subjects with lower aerobic capacity.

Muscular strength as an index of health

Hand grip strength, assessed by the manual dynamometer test, is currently considered to be a reliable marker of health and wellbeing (CitationLord et al 2003; CitationChang et al 2004; CitationHulsmann et al 2004) and a potent predictor of mortality and the expectancy of being able to live independently (CitationMetter et al 2002; CitationSeguin and Nelson 2003). Figure shows the decline in this quality with the passage of time. Given its importance, efforts should be made to reduce the errors associated with its measurement (CitationRuiz et al 2002).

Figure 4 Deterioration of hand grip strength with age (cross-sectional study performed on healthy Spanish people [222 men, and 208 women]).

![Figure 4 Deterioration of hand grip strength with age (cross-sectional study performed on healthy Spanish people [222 men, and 208 women]).](/cms/asset/5dfcb7c4-24db-4f0e-8375-402bc55549da/dcia_a_13213_f0004_b.jpg)

A recent study performed with patients with heart disease shows that the isokinetic strength of the extensor muscles (quadriceps) and especially the flexors of the knee (ischiotibial muscles), is strongly associated with mortality – and has even better predictive power than variables such as VO2max (CitationHulsmann et al 2004). In addition, the maintenance of good muscular tone in the legs is directly related to a drastic reduction in the number of falls (and therefore of bone fractures) suffered (CitationLord et al 2003; CitationChang et al 2004).

Assessment of physical fitness

Knowing a person’s true physical fitness is fundamental for prescribing any program of physical exercise to help prevent the consequences of aging. Physical fitness is assessed by a battery of validated tests that provides a complete evaluation of the physical qualities associated with physical fitness (CitationLaukkanen et al 1992; EC and UKK 1998). These tests should always include the assessment of aerobic capacity, the muscular strength of the upper and lower body, flexibility, and psychokinetic capacities (ie, agility, coordination, balance, visual and auditory reaction times). Table shows the tests most commonly used in clinical practice for the evaluation of physical fitness orientated towards anti-aging therapy.

Table 2 Some of the most used clinical tests for assessing physical fitness with a view to anti-aging therapy

Prescription of exercise as an anti-aging therapy

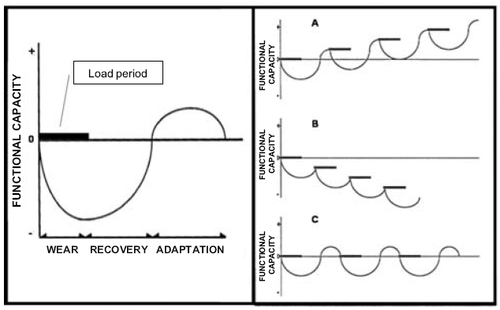

The prescription of exercise with the aim of attenuating the physiological consequences of aging should be orientated towards increasing daily physical activity and improving physical fitness. The aim is to provoke optimum stimulation (training) in order to achieve maximum adaptation, but without over-stimulating (Figure ). In exercise physiology terms, the aim is to train to the maximum but not to overtrain (CitationCastillo and Gutiérrez 2001; CitationGutiérrez et al 2003). Thus, it is very important to correctly individualize exercise and to monitor functional adaptation; this will allow adjustments to be made according to the medical and physiological condition of the subject at each moment. In general terms, exercise prescription is based upon the frequency, intensity and duration of training, the type of activity, and the initial level of fitness (the main determinant).

Figure 5 Left: Physical exercise (Load period) implies organic wear that reduces functional capacity (Wear). With rest and correct nutrition, lost functional capacity can be recovered (Recovery). This is followed by a period of overcompensation to exertion (Adaptation). This forms the theoretical basis of training. Right: The timing of training (A, B o C) influences functional capacity - either improving it (A), causing it to worsen (B) or having no effect (C) (CitationDelgado et al 2004).

Exercise prescription for aerobic training

Physical activities that develop cardiorespiratory fitness lie at the heart of any exercise program (CitationDelgado et al 2004). These activities are designed to improve both the capacity and efficiency of cardiovascular and metabolic systems. They also help in the control and reduction of body fat.

The results of aerobic exercise, eg, walking, are very positive, especially for cardiovascular health. These improvements are independent of race, sex, age, and body mass index (CitationManson et al 2002). A program of regular aerobic exercise of three to six months duration can improve aerobic capacity by 15%–30% (CitationACSM 1998). Undertaking weekly aerobic exercise lasting 60–90 minutes leads to significant reductions in the systolic and diastolic blood pressure in hypertensive men and women. No further improvement is seen if this time is extended (CitationIshikawa-Takata et al 2003). There is substantial evidence that aerobic training exerts a favorable influence on the blood lipid and lipoprotein profiles at any age (CitationPate et al 1995; CitationFletcher et al 1996). The dose-response relationships between the amount of exercise and favorable blood lipid and lipoproteins changes suggest that exercise can exert a positive influence on blood lipids even at low training volumes, although the effects may not be observed until certain exercise thresholds are met (CitationACSM 1998). Another important benefit of aerobic exercise is the reduction it causes in insulin resistance (CitationSato et al 2003). Similar results have been obtained in the treatment of diabetes and metabolic syndrome (CitationWatkins et al 2003; CitationSwartz et al 2003). Finally, aerobic exercise performed for 30 min at least three times per week has been shown to have a potent therapeutic effect on certain mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety and panic syndromes (CitationBabyak et al 2000; CitationPaluska and Schwenk 2000).

A training frequency of 3–5 days a week is recommended. It is preferable to avoid single, hard bouts of exercise once a week (CitationRuiz et al 2004). Training intensity should be at some 55%/65%–90% of the maximum heart rate, or of the maximum reserve heart rate (maximum HR –rest HR) (CitationACSM 1998). Lower intensity values, eg, 40%–49% of the maximum reserve heart rate and 55%–64% of the maximum heart rate, are recommended for unfit individuals. The duration of training should be 30–60 min of continuous or intermittent (10 min or longer bouts accumulated over the day) aerobic activity. The duration is dependent on the intensity of the activity; thus, lower-intensity activity should be conducted over 30 min or more, while individuals training at higher intensity levels should do so for 20 min or more. Because of the importance of “total fitness”, that this is more readily attained with exercise sessions of longer duration, and given the potential hazards and adherence problems associated with high-intensity activity, moderate-intensity activity of longer duration is recommended for adults not training for athletic competition (CitationACSM 1998). Any activity that uses the large muscle groups (eg, walking, hiking, running, jogging, cycling, cross-country skiing, aerobic dancing, rope skipping, rowing, stair climbing, swimming, skating, endurance game activities, etc.), that can be maintained continuously and is rhythmical and aerobic in nature, is recommendable. Brisk walking is preferable for older people since this has a low impact on the joints, although recreational sports are also recommended. These guidelines for healthy adults are those published by the American College of Sports Medicine (CitationACSM 1998).

Prescribing exercise for improving muscular strength

Resistance training has been shown to be the most effective method for developing skeletomuscular strength, and it is currently prescribed by many major health organizations for improving health and fitness (CitationAACPR 1999; CitationACSM 2002). Resistance training reduces the risk factors associated with coronary heart disease (CitationFahlman et al 2002), non-insulin-dependent diabetes (CitationFluckey et al 1994), and colon cancer (CitationKoffler et al 1992), it prevents osteoporosis (Citationvon Stengel et al 2005), promotes weight loss and weight maintenance, improves dynamic stability, preserves functional capacity (CitationEvans 1999), and fosters psychological well-being (CitationEwart 1989). These benefits can be safely obtained when an individualized program is prescribed.

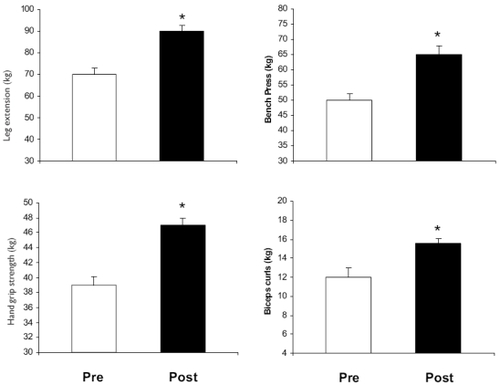

Appropriate strength training produces a significant increase in muscular strength in a relatively short time, as shown in studies that have followed men and women (aged 45–65 years) involved in a six month training program (unpublished; Figure ). Table shows the gains in strength that can be obtained.

Table 3 Strength gains after a resistance training period in older people

Figure 6 Effects of a resistance training program (3 days/week) for 3 months on maximum strength in older people.

Muscular strength and endurance can be developed by means of static (isometric) or dynamic (isotonic or isokinetic) exercises (CitationACSM 2002). Although each type of training has its advantages and limitations, for healthy adults, dynamic resistance exercises are recommended since they best mimic everyday activities (CitationIki et al 2002). Resistance training for the average participant should be rhythmical, performed at a moderate-to-slow and controlled speed, involve a full range of motion, and demand a normal breathing pattern during lifting movements. Heavy resistance exercise can cause a dramatic acute increase in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure (CitationLachowetz et al 1998), especially when a Valsalva manoeuvre is undertaken (CitationACSM 2002).

Resistance training should be an integral part of any adult fitness program and should be of sufficient intensity to enhance strength, muscular endurance, and maintain fat-free mass. Resistance training should be progressive in nature, individualized, and provide a stimulus to all the major muscle groups. In the American College of Sports Medicine’s Position Stand (CitationACSM 2002), “The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adults,” the initial standard for a resistance training program was the performance of one set of 8–12 repetitions of 8–10 exercises, including one exercise for all major muscle groups (10–15 repetitions for older or more frail persons) (CitationArmstrong 1984).

It is recommended that novice lifters train with loads of 60%–70% of a one repetition maximum (RM) for 8–12 repetitions. Advanced individuals should use loading ranges of 70%–90% of the RM in a periodic fashion to maximize muscular strength (CitationACSM 2002). For progression in those individuals training at a specific RM load (eg, 8–12 repetitions), it is recommended that a 2%–10% increase be applied on the basis of muscle group size and involvement (ie, greater load increases may be used for large muscle groups and for multiple-joint exercises) when the individual can perform at his/her current intensity for one or two repetitions more than the desired number in two consecutive training sessions (CitationACSM 2002).

Recently, it has been reported that power training is more effective than strength training for maintaining bone mineral density in postmenopausal women (Citationvon Stengel et al 2005). This suggests that fast movements provide greater benefit than slow movements.

Prescribing exercise for flexibility

Flexibility exercise usually supplements exercises performed during the warm-up or cool-down period, and are useful for those who have poor flexibility or muscle and joint problems (such as low back pain).

Flexibility exercises do not improve resistance or strength, but several studies have shown that they increase muscular performance and tendon flexibility, and that they extend the amplitude of movement and the functionality of the joints (CitationACSM 1998). It is therefore a good idea to incorporate these exercises into any program directed towards improving physical fitness (CitationPollock et al 2000).

A general stretching program that exercises the major muscle/tendon groups (lower extremity anterior chain, lower extremity posterior chain, shoulder girdle, etc) should be developed using static, ballistic, or modified proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (contract/relax, hold/relax, active/assisted) techniques. Static stretches should be held for 10–20 s, whereas proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation techniques should include a 6 s contraction followed by 10–20 s assisted stretch (CitationACSM 2000).

Conclusion

Aging is a physiological process that can be influenced for the better (delaying it) or worse (accelerating it). The most recent scientific evidence shows that regularly and appropriately practiced physical exercise, in order to improve physical fitness, is currently the best way to delay or even prevent the consequences of aging. Such exercise always brings benefits, irrespective of the age, sex, health, or the physical condition of the person who undertakes it. In contrast, a lack of exercise clearly accelerates aging and its consequences, including one’s physical appearance. Among people of the same age and genetic background, those who remain physically active, who eat correctly, and who avoid risk factors, look younger and maintain a more youthful nature.

Recent research has shown that a person’s degree of physical fitness is an excellent predictor of life expectancy and quality of life. Improving one’s physical fitness increases life expectancy and prevents age-associated diseases. To be effective, the aerobic capacity needs to be increased, along with strength and joint mobility.

In conclusion, potentiating physical fitness is undoubtedly the best medicine available today for combating the inexorable process of aging.

References

- [AACPR] American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation1999Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention Programs3rd EdChampaign, ILHuman Kinetics

- AbbottA2004Growing old gracefullyNature4281161815014466

- [ACSM] American College of Sports Medicine1998Position stand: the recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness, and flexibility in healthy adultsMed Sci Sports Exerc30975919624661

- [ACSM] American College of Sports Medicine2002Position stand on progression models in resistance training for healthy adultsMed Sci Sports Exerc343648011828249

- ArmstrongRB1984Mechanisms of exercise-induced delayed onset muscular soreness: a brief reviewMed Sci Sports Exerc16529386392811

- BabyakMBlumenthalJAHermanS2000Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 monthsPsychosom Med62633811020092

- BaladyGJ2002Survival of the fittest-more evidenceN Engl J Med346852411893798

- BarnesDEYaffeKSatarianoWA2003A longitudinal study of cardiorespiratory fitness and cognitive function in healthy older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc514596512657064

- BertoliADi DanieleNCeccobelliM2003Lipid profile, BMI, body fat distribution, and aerobic fitness in men with metabolic syndromeActa Diabetol40130S133S

- BlairSNBrodneyS1999Effects of physical inactivity and obesity on morbidity and mortality: current evidence and research issuesMed Sci Sports Exerc31S6466210593541

- BlairSNKohlHWBarlowCE1995Changes in physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy and unhealthy menJAMA273109387707596

- BlumenthalJABabyakMAMooreKA1999Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depressionArch Intern Med15923495610547175

- CapodaglioPCapodaglioEMFerriA2005Muscle function and functional ability improves more in community-dwelling older women with a mixed-strength training programmeAge Ageing34141715713857

- CarnethonMRGiddingSSNehgmeR2003Cardiorespiratory fitness in young adulthood and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factorsJAMA290309210014679272

- CastilloMJGutiérrezA2001Entrenamiento y sobre-entrenamiento. Entrenar para ganar o entrenar para perderTécnicas de entrenamiento para deportes de equipoGranadaEditorial Universitaria

- ChangJTMortonSCRubensteinLZ2004Interventions for the prevention of falls in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trialsBMJ32868015031239

- ColcombeSJEricksonKIRazN2003Aerobic fitness reduces brain tissue loss in ageing humansJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci581768012586857

- DelgadoMGutiérrezACastilloMJ2004Entrenamiento físico-deportivo y alimentación. De la infancia a la edad adulta3rd edBarcelonaPaidotribo

- [EC and UKK] European Council and UKK institute1998Eurofit para adultos: evaluación de la aptitud física en relación con la saludEd. Espanola. MadridMinisterio de Educación y Cultura

- EnglundULittbrandHSondellA2005A 1-year combined weight-bearing training program is beneficial for bone mineral density and neuromuscular function in older womenOsteoporos Int1611172316133653

- EvansWJ1999Exercise training guidelines for the elderlyMed Sci Sports Exerc3112179927004

- EvensonKRStevensJCaiJ2003The effect of cardiorespiratory fitness and obesity on cancer mortality in women and menMed Sci Sports Exerc35270712569216

- EwartCK1989Psychological effects of resistive weight training: implications for cardiac patientsMed Sci Sports Exerc2168382696855

- FahlmanMMBoardleyDLambertCP2002Effects of endurance training and resistance training on plasma lipoprotein profiles in elderly womenJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci575460

- FletcherGFBaladyGBlairSN1996Statement on exercise: benefits and recommendations for physical activity programs for all Americans: a statement for health professionals by the Committee on Exercise and Cardiac. Rehabilitation of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart AssociationCirculation94857628772712

- FluckeyJDHickeyMBrambrinkJK1994Effects of resistance exercise on glucose tolerance in normal and glucose-intolerant subjectsJ Appl Physiol771087927836108

- GoodwinRD2003Association between physical activity and mental disorders among adults in the United StatesPrev Med3669870312744913

- GulatiMPandeyDKArnsdorfMF2003Exercise capacity and the risk of death in women: the St James Women Take Heart ProjectCirculation1081554912975254

- GutiérrezAGonzález-GrossMRuizJR2003Exposure to hypoxia decreases growth hormone response to physical exercise in untrained subjectsJ Sports Med Phys Fitness43554814767420

- HenwoodTRTaaffeDR2005Improved physical performance in older adults undertaking a short-term programme of high-velocity resistance trainingGerontology511081515711077

- HulsmannMQuittanMBergerR2004Muscle strength as a predictor of long-term survival in severe congestive heart failureEur J Heart Fail6101715012925

- HungCDaubBBlackB2004Exercise training improves overall physical fitness and quality of life in older women with coronary artery diseaseChest12610263115486358

- IkiMSaitoYDohiY2002Greater trunk muscle torque reduces postmenopausal bone loss at the spine independently of age, body size, and vitamin D receptor genotype in Japanese womenCalcif Tissue Int71300712154394

- Ishikawa-TakataKOhtaTTanakaH2003How much exercise is required to reduce blood pressure in essential hypertensives: A dose-response studyAJH166293312878367

- IzquierdoMIbanezJHakkinenK2004Once weekly combined resistance and cardiovascular training in healthy older menMed Sci Sports Exerc364354315076785

- KirkcaldyBDShephardRJSiefenRG2002The relationship between physical activity and self-image and problem behaviour among adolescentsSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol375445012395145

- KofflerKHMenkesRARedmondWE1992Strength training accelerates gastrointestinal transit in middle-aged and older menMed Sci Sports Exerc24415191560736

- KurlSLaukkanenJARauramaaR2003Cardiorespiratory fitness and the risk for stroke in menArch Intern Med1631682812885683

- LachowetzTEvonJPastiglioneJ1998The effect of an upper body strength program on intercollegiate baseball throwing velocityJ Strength Cond Res1211619

- LakkaTALaaksonenDELakkaHM2003Sedentary lifestyle, poor cardiorespiratory fitness, and the metabolic syndromeMed Sci Sports Exerc3512798612900679

- LaukkanenJALakkaTARauramaaR2001Cardiovascular fitness as a predictor of mortality in menArch Intern Med1618253111268224

- LaukkanenROjaPPasanenM1992Validity of a two kilometre walking test for estimating maximal aerobic power in overweight adultsInt J Obes Relat Metab Disord1626381318280

- LeeCDBlairSN2002Cardiorespiratory fitness and smoking-related and total cancer mortality in menMed Sci Sports Exerc34735911984287

- LeeCDFolsomARBlairSN2003Physical activity and stroke riskStroke34247514500932

- LordSRCastellSCorcoranJ2003The effect of group exercise on physical functioning and falls in frail older people living in retirement villages: a randomized, controlled trialJ Am Geriatr Soc5116859214687345

- MansonJEGreenlandPLaCroixAZ2002Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in womenN Engl J Med3477162512213942

- MetterEJTalbotLASchragerM2002Skeletal muscle strength as a predictor of all-cause mortality in healthy menJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci57B3596512242311

- MoraSRedbergRFCuiY2003Ability of exercise testing to predict cardiovascular and all-cause death in asymptomatic women: a 20-year follow-up of the lipid research clinics prevalence studyJAMA2901600714506119

- MyersJPrakashMFroelicherV2002Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testingN Engl J Med34679380111893790

- MyersJ2003Exercise and cardiovascular healthCirculation1072512515732

- PaluskaSASchwenkTL2000Physical activity and mental health: Current ConceptsSports Med291678010739267

- PateRRPrattMBlairSN1995Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports MedicineJAMA27340277823386

- PiepoliMFDavosCFrancisDP2004Exercise training meta-analysis of trials in patients with chronic heart failure (ExTraMATCH)BMJ32818914729656

- PollockMLFranklinBABaladyGJ2000AHA Science Advisory. Resistance exercise in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease: benefits, rationale, safety, and prescription: An advisory from the Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association; Position paper endorsed by the American College of Sports MedicineCirculation1018283310683360

- RuizJRMesaJLCastilloMJ2002Hand size influences optimal grip span in women but not in menJ Hand Surg27897901

- RuizJRMesaJLMMingoranceI2004Sports Requiring Stressful Physical Exertion Cause Abnormalities in Plasma Lipid ProfileRev Esp Cardiol5749950615225496

- SatoYNagasakiMNakaiN2003Physical exercise improves glucose metabolism in lifestyle-related diseasesExp Biol Med228120812

- SawadaSSLeeIMMutoT2003aCardiorespiratory fitness and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: prospective study of Japanese menDiabetes Care2629182214514602

- SawadaSSMutoTTanakaH2003bCardiorespiratory Fitness and Cancer Mortality in Japanese Men: A Prospective StudyMed Sci Sports Exerc3515465012972875

- SeguinRNelsonME2003The benefits of strength training for older adultsAm J Prev Med25S1419

- SeibaekMVestergaardHBurchardtH2003Insulin resistance and maximal oxygen uptakeClin Cardiol265152014640466

- StrawbridgeWJDelegerSRobertsRE2002Physical activity reduces the risk of subsequent depression for older adultsAm J Epidemiol1563283412181102

- SwartzAMStrathSJBassettDR2003Increasing daily walking improves glucose tolerance in overweight womenPrev Med373566214507493

- ThompsonKRMikeskyAEBahamondeRE2003Effects of physical training on proprioception in older womenJ Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact32233115758345

- von StengelSKemmlerWKLauberD2005Power training is more effective than strength training for maintaining bone mineral density in postmenopausal womenJ Appl Physiol3S875087

- WatkinsLLSherwoodAFeinglosM2003Effects of exercise and weight loss on cardiac risk factors associated with syndrome XArch Intern Med16318899512963561