Abstract

Depression is common in COPD patients. Around 40% are affected by severe depressive symptoms or clinical depression. It is not easy to diagnose depression in COPD patients because of overlapping symptoms between COPD and depression. However, the six-item Hamilton Depression Subscale appears to be a useful screening tool. Quality of life is strongly impaired in COPD patients and patients’ quality of life emerges to be more correlated with the presence of depressive symptoms than with the severity of COPD. Nortriptyline and imipramine are effective in the treatment of depression, but little is known about the usefulness of newer antidepressants. In patients with milder depression, pulmonary rehabilitation as well as cognitive-behavioral therapy are effective. Little is known about the long-term outcome in COPD patients with co-morbid depression. Preliminary data suggest that co-morbid depression may be an independent protector for mortality.

Introduction

It is recognized that many physical illnesses may have a direct link to the appearance of depressive syndromes and many studies have documented a high rate of depression and anxiety among patients suffering from COPD (CitationYellowlees et al 1987; CitationKarajgi et al 1990; Citationvan Ede et al 1999; CitationAghanwa and Erhabor 2001; CitationDowson et al 2001; CitationMikkelsen et al. 2004). COPD is a severe treatment-resistant pulmonary disease with varying impact on the patient’s general physical condition, functioning, and quality of life. It is assumed that a successful treatment of a co-morbid depression leads to improved quality of life and less restricted general functioning (CitationRodin et al 1991). However, the evaluation of psychopathology in medical patients, eg, those with COPD, presents special problems. Almost all self-report and clinicians’ rating scales for detecting depression is biased by a large number of items dealing with somatic symptoms. For example, the Hamilton Depression Scale (Ham-D) (CitationHamilton 1960; CitationHamilton 1967) has eight or nine items reflecting somatic complaints or changes in somatic functioning. Such items are also included in the official diagnostic criteria for depression, ie, ICD-10 (CitationWHO 1992) and DSM-IV (CitationAPA 1994). Therefore, it is difficult to decide when these somatic symptoms are secondary to depression and when they are a secondary to the somatic illness.

This review will focus on our knowledge about epidemiology, diagnostic procedures, treatment aspects, and quality of life in COPD patients with co-morbid depression. We will also summarize recent findings concerning how the interaction between depression and COPD may affect patients’ survival.

Prevalence and co-morbidity

The prevalence of depressive symptoms in COPD patients varies considerably. Two recent reviews (Citationvan Ede et al 1999; CitationMikkelsen et al 2004) found a prevalence of depression, ranging from 6% to 57%.

CitationVan Ede et al (1999) found a prevalence ranging from 6% to 42%. They emphasized that only 4 out of 34 studies had a control group (CitationMcSweeny et al 1982; CitationPrigatano et al 1984; CitationIsoaho et al 1995; CitationEngstrom et al 1996). However, all four studies showed that the prevalence was higher in the study group, ie, the COPD patients, but the difference was statistically significant in two of the studies only (CitationMcSweeny et al 1982; CitationPrigatano et al 1984).

CitationMikkelsen et al (2004) pointed out that two of the latest prevalence studies identified clinically significant depressive symptoms in 42%–57% of COPD patients (CitationYohannes et al 2000; CitationLacasse et al 2001). The major co-morbidity studies are summarized in .

Table 1 Summary of co-morbidity studies: Prevalence of psychiatric co-morbidity in COPD patients

There are many possible explanations for these differing results. Many studies are performed on small samples and are lacking control groups. The way the psychiatric diagnoses are obtained also varies. Some studies utilize established diagnostic criteria, other studies only use clinical assessments or self-reported symptoms. Most studies contain no formal data analysis and only simple descriptive statistics. Finally, differences in the objective characteristics and severity of COPD may contribute to the variations in prevalence figures.

In summary, the prevalence of depression is high in COPD patients, for both occurrence of “significant symptoms” and clinical depression. Although there are large variations in prevalence figures, the latest studies point out a prevalence of more than 40% (CitationYohannes et al 2000; CitationStage et al 2003).

Quality of life

According to CitationMcSweeny et al (1982), quality of life is concerned with the following four dimensions: emotional functioning, social-role functioning, activities of daily living (ADL), and recreational pastimes.

Compared with persons without physical illness, COPD patients have impaired quality of life (CitationMcSweeny et al 1982; CitationPrigatano et al 1984; CitationYohannes et al 1998).

COPD patients with co-morbid depression have impaired quality of life compared with COPD patients without depression (CitationBosley et al 1996; CitationYohannes et al 1998; CitationKim et al 2000; CitationAydin and Ulusahin 2001; CitationFelker et al 2001; CitationYohannes et al 2003). CitationYohannes et al (2003) also showed that COPD patients’ quality of life was more correlated to the presence of depressive symptoms than to the severity of COPD as measured by FEV1. This phenomenon was also demonstrated by CitationKim et al (2000). In a different study 28 patients were followed over 4 years, but even though their physical condition got better because of aggressive medical treatment, no improvement in quality of life was shown (Citationvan Schayck 1997).

In spite of this, co-morbid depression does not seem to worsen the physical aspects of COPD (CitationLight et al 1985; CitationBorak et al 1998). For example CitationLight et al (1985) found no significant correlation between the level of depression or anxiety and the distance that the patient could walk in 12 minutes.

Diagnostic aspects

Today, the ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria for depression are the most common diagnostic tools. When it comes to depression in patients with severe somatic illness, the validity of the ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria for depression may to a certain degree be questioned because it is difficult to decide when somatic symptoms are secondary to depression and when they are secondary to somatic illness. In fact, the ICD-10 has a general exclusion criterion that the depressive episode is not attributed to any organic cause, while the DSM-III-R/IV is less restrictive on the matter. Severe COPD could lead to somatic symptoms impossible to separate from depressive symptoms. CitationEndicott (1984) has therefore suggested replacement of the somatic symptoms in the DSM-III-R/IV criteria with alternative non-somatic depressive symptoms, ie, replace change in appetite–weight with tearfulness–depressed appearance, sleep disturbances with social withdrawal, fatigue or loss of energy with brooding–pessimism, and diminished ability to think or concentrate with lack of reactivity to environmental events. These modifications have to some extent been validated (CitationRapp and Vrana 1989; CitationKathol et al 1990) and may be they should be used when trying to identify depression in subjects with somatic illness. However, as long as there is no method for deciding whether the somatic symptoms are secondary to depression or COPD, the classification will be biased.

In a recent study, we tested the internal and external validity of the six-item Hamilton Depression subscale (HAM-D-6) in a sample of 49 COPD patients (CitationStage et al 2003). We found that HAM-D-6 could be used as a screening instrument for depression in COPD patients, ie, the sensitivity of the test was 0.91, the specificity was 0.88, the positive predictive value 0.87, and the negative predictive value was 0.91 when the cut-off score was set to 7 or more on HAM-D-6. The HAM-D-6 items are shown in . If the HAM-D-6 total score is 10 or more, treatment with an antidepressant is often required.

Table 2 The six-item Hamilton Depression subscale (HAM-D-6)

Treatment of depression in COPD patients

Antidepressants

The tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have been tested in a few studies (CitationLight et al 1986; CitationSharma et al 1988; CitationBorson et al 1992). Although the results are contradictory, there is some evidence that TCAs are effective. CitationBorson et al (1998) studied 30 patients who completed a 12-week, randomized, controlled trial of nortriptyline. Nortriptyline was clearly superior to placebo for treatment of depression. Nortriptyline treatment was accompanied by marked improvements in anxiety, certain respiratory symptoms, overall physical comfort, and day-to-day function; placebo effects were negligible. Physiological measures reflecting pulmonary insufficiency were generally unaffected by treatment. It has also been shown that imipramine in combination with diazpam is effective (CitationSharma et al 1988), while doxepine failed in a placebo-controlled trial (CitationLight et al 1986). shows treatment information about imipramine and nortriptyline. Note that the doses of imipramine and nortriptyline are lower than in patients without co-morbid COPD, mainly because most COPD patients are elderly. Treating elderly patients with TCAs like imipramine and nortriptyline is not unproblematic due to an increased risk of severe side-effects. The decision to start a TCA treatment balances the documented efficacy and the increased risk of side-effects in elderly patients.

Table 3 Treatment information about the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) imipramine and nortriptyline: the decision to start a TCA treatment balances the documented efficacy and the increased risk of side-effects in elderly patients

Little is known about the effectiveness of newer antidepressants like the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) but smaller studies and case reports suggests that SSRIs are well tolerated although the compliance may be poor (CitationPapp et al 1995; CitationSmoller et al 1998; CitationYohannes et al 2001).

Benzodiazepines and other drugs

Benzodiazepines have anxiolytic effect in COPD patients (CitationNutt et al 1999), but may cause respiratory depression. Therefore, benzodiazepines should be considered only if other anxiolytic agents have failed.

Buspirone has been tested in COPD patients, but the results are not conclusive (CitationArgyropoulou et al 1993; CitationSingh et al 1993).

Non-pharmacological treatment

In general the non-pharmocological treatment of depression in COPD is limited to patients with milder depression and here multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation as well as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) appears effective (CitationBorson et al 1998).

CBT for this group of patients includes increasing the patients’ body-awareness by exercises in relaxation and breathing. The cognitive elements of the treatment are aimed at identifying automatic thoughts and promote a more adaptive cognitive style. Graduated exposure and desensitizing is then attempted to reduce fears of symptoms as well as alleviating the panic reactions. CitationEiser et al (1997) found that six sessions of CBT resulted in sustained improvement in exercise tolerance in patients suffering from severe COPD and anxiety. In a recent randomized clinical trial (CitationKunik et al 2001), a single 2-hour session of group CBT and weekly calls over 6 weeks reduced both depressed mood and anxiety. The effect was significantly better than in the control group (2-hour education and weekly calls). There were no improvements in physical functioning in either group.

Pulmonary rehabilitation programs have also been described for COPD patients for co-morbid anxiety and depression. By means of progressive exercise, training of respiratory function, and psycho-education, patients obtained better exercise tolerance, less dyspnea, and better quality of life (CitationRies et al 1995; CitationEmery et al 1998; CitationWithers et al 1999; Citationde Godoy and de Godoy 2003; CitationGaruti et al 2003).

Does depression affect the long-term outcome in COPD patients?

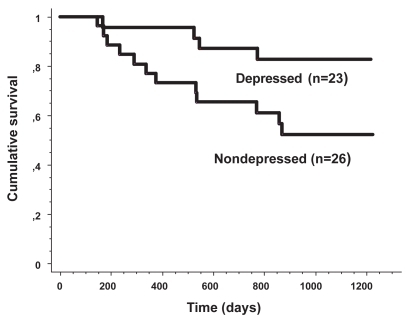

Few studies have examined the long-term outcome of depressed COPD patients. Yet we recently published a study focusing on the survival in COPD patients (CitationStage et al 2005). We found that co-morbid depression significantly reduced the mortality risk at follow-up. The impact of depression remained after control for FEV1, the only multivariate significant predictor of mortality in the data set (hazard ratio, 0.27; 95% confidence interval, 0.09–0.84; p=0.024). The cumulative mortality for depressed and non-depressed COPD patients is shown in . We concluded that depression appears to be an independent protector for mortality, although we have no clues about the underlying mechanism. However, the study included only 49 patients and it should be replicated in a larger sample.

Figure 1 Cumulative mortality for depressed and non-depressed COPD patients. Reprinted from CitationStage KB, Middelboe T, Pisinger C. 2005. Depression and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Impact on survival. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 111:320–3. Copyright © 2005 with permission from Blackwell Publishing.

Conclusion

Depression is very common in COPD patients. Around 40% are affected by severe depressive symptoms or clinical depressions. It is not easy to diagnose depression in COPD patients because of the overlapping symptoms between COPD and depression. However, the six-item Hamilton Depression Subscale (HAM-D-6) appears to be a useful screening tool. Quality of life is strongly impaired in COPD patients and patients’ quality of life emerges to be more correlated with the presence of depressive symptoms than with the severity of COPD. Nortriptyline and imipramine are effective in the treatment of depression, but little is known about the usefulness of newer antidepressants. In patients with milder depressionm, pulmonary rehabilitation as well as cognitive-behavioral therapy seem effective. Little is known about the long-term outcome in COPD patients with co-morbid depression. Preliminary data suggest that co-morbid depression may be an independent protector for mortality.

Much more research is needed concerning epidemiology, psychopathology, quality of life, treatment, and long-term outcome.

The key points of this review are shown in .

References

- AghanwaHSErhaborGE2001Specific psychiatric morbidity among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a Nigerian general hospitalJ Psychosom Res501798311369022

- [APA] American Psychiatric Association1994Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4rd edition (DSM-IV)Washington, DCAPA

- ArgyropoulouPPatakasDKoukouA1993Buspirone effect on breathlessness and exercise performance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration60216208265878

- AydinIOUlusahinA2001Depression, anxiety comorbidity, and disability in tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: applicability of GHQ-12Gen Hosp Psychiatry23778311313075

- BorakJChodosowskaEMatuszewskiA1998Emotional status does not alter exercise tolerance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J1237039727787

- BorsonSClaypooleKClaypooleK1998Depression and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease:treatment trialsSemin Clin Neuropsychiatry31153010085198

- BorsonSMcDonaldGJGayleT1992Improvement in mood, physical symptoms, and function with nortriptyline for depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePsychosomatics331902011557484

- BosleyCMCordenZMReesPJ1996Psychological factors associated with use of home nebulized therapy for COPDEur Respir J92346508947083

- de GodoyDVde GodoyRF2003A randomized controlled trial of the effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Phys Med Rehabil841154712917854

- DowsonCLaingRBarracloughR2001The use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease:a pilot studyN Z Med J114447911700772

- EiserNWestCEvansS1997Effects of psychotherapy in moderately severe COPD:a pilot studyEur Respir J10158149230251

- EmeryCFScheinRLHauckER1998Psychological and cognitive outcomes of a randomized trial of exercise among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseHealth Psychol17232409619472

- EndicottJ1984Measurement of depression in patients with cancerCancer53224376704912

- EngstromCPPerssonLOLarssonS1996Functional status and well being in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with regard to clinical parameters and smoking:a descriptive and comparative studyThorax51825308795672

- FelkerBKatonWHedrickSC2001The association between depressive symptoms and health status in patients with chronic pulmonary diseaseGen Hosp Psychiatry23566111313071

- GarutiGCilioneCDell’OrsoD2003Impact of comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation on anxiety and depression in hospitalized COPD patientsMonaldi Arch Chest Dis59566114533284

- HamiltonM1960A rating scale for depressionJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry26566214399272

- HamiltonM1967Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illnessBr J Soc Clin Psychol6278966080235

- IsoahoRKeistinenTLaippalaP1995Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and symptoms related to depression in elderly personsPsychol Rep76287977770581

- KarajgiBRifkinADoddiS1990The prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Psychiatry14720012301659

- KatholRGMutgiAWilliamsJ1990Diagnosis of major depression in cancer patients according to four sets of criteriaAm J Psychiatry147102142375435

- KimHFKunikMEMolinariVA2000Functional impairment in COPD patients:the impact of anxiety and depressionPsychosomatics414657111110109

- KunikMEBraunUStanleyMA2001One session cognitive behavioural therapy for elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePsychol Med317172311352373

- LacasseYRousseauLMaltaisF2001Prevalence of depressive symptoms and depression in patients with severe oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil2180611314288

- LightRWMerrillEJDesparsJ1986Doxepin treatment of depressed patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med1461377803521524

- LightRWMerrillEJDesparsJ1985Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Relationship to functional capacityChest873583965263

- McSweenyAJGrantIHeatonRK1982Life quality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med14247387065785

- MikkelsenRLMiddelboeTPisingerC2004Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A reviewNord J Psychiatry58657014985157

- NuttDBallengerJCLepineJP1999Panic disordersClinical diagnosis, managment and mechanismsLondonMartin Dunitz

- PappLAWeissJRGreenbergHE1995Sertraline for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbid anxiety and mood disordersAm J Psychiatry15215317573598

- PrigatanoGPWrightECLevinD1984Quality of life and its predictors in patients with mild hypoxemia and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med144161396380440

- RappSRVranaS1989Substituting nonsomatic for somatic symptoms in the diagnosis of depression in elderly male medical patientsAm J Psychiatry146119712002669537

- RiesALKaplanRMLimbergTM1995Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiologic and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Intern Med122823327741366

- RodinGCravenJLittlefieldC1991Depression in the medically illAn integrated approachNew YorkBrunner/Mazel

- SharmaTNGoyalRLGuptaPR1988Psychiatric disorders in COPD with special reference to the usefulness of imipramine-diazepam combinationIndian J Chest Dis Allied Sci3026383255690

- SinghNPDesparsJAStansburyDW1993Effects of buspirone on anxiety levels and exercise tolerance in patients with chronic airflow obstruction and mild anxietyChest10380048449072

- SmollerJWPollackMHSystromD1998Sertraline effects on dyspnea in patients with obstructive airways diseasePsychosomatics392499538672

- StageKBMiddelboeTPisingerC2003Measurement of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Nord J Psychiatry5729730112888404

- StageKBMiddelboeTPisingerC2005Depression and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Impact on survivalActa Psychiatr Scand111320315740469

- van EdeLYzermansCJBrouwerHJ1999Prevalence of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease:a systematic reviewThorax546889210413720

- van SchayckCP1997Measurement of quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePharmacoeconomics1113810172915

- WithersNJRudkinSTWhiteRJ1999Anxiety and depression in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the effects of pulmonary rehabilitationJ Cardiopulm Rehabil19362510609186

- [WHO] World Health Organization1992The ICD-10 Classification Of Mental and Behavioural DisordersGenevaWHO

- YellowleesPMAlpersJHBowdenJJ1987Psychiatric morbidity in patients with chronic airflow obstructionMed J Aust14630573821636

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJ2000Depression and anxiety in elderly outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, and validation of the BASDEC screening questionnaireInt J Geriatr Psychiatry151090611180464

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJ2003Prevalence of sub-threshold depression in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry18412612766917

- YohannesAMConnollyMJBaldwinRC2001A feasibility study of antidepressant drug therapy in depressed elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry16451411376459

- YohannesAMRoomiJWatersK1998Quality of life in elderly patients with COPD:measurement and predictive factorsRespir Med92123169926154