Abstract

Respiratory disease has never received priority in relation to its impact on health. Estimated DALYs lost in 2002 were 12% globally (similar for industrialized and developing countries). Chronic airflow limitation (due mainly to asthma and COPD) alone affects more than 100 million persons in the world and the majority of them live in developing countries. International guidelines for management of asthma (GINA) and COPD (GOLD) have been adopted and their cost-effectiveness demonstrated in industrialized countries. As resources are scarce in developing countries, adaptation of these guidelines using only essential drugs is required. It remains for governments to set priorities. To make these choices, a set of criteria have been proposed. It is vital that the results of scientific investigations are presented in these terms to facilitate their use by decision-makers. To respond to this emerging public health problem in developing countries, WHO has developed 2 initiatives: “Practical Approach to Lung Health (PAL)” and the Global Alliance Against Chronic Respiratory Diseases (GARD)”, and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (The Union) has launched a new initiative to increase affordability of essential asthma drugs for patients in developing countries termed the “Asthma Drug Facility” (ADF), which could facilitate the care of patients living in these parts of the world.

Introduction

Chronic respiratory diseases have never, in any area of the world, been accorded a priority relative to their extent and impact. No political jurisdiction (rich or poor) proportionally commits resources to chronic respiratory diseases equivalent to the burden they represent in the community, whether for research, prevention, or clinical services. It was only in 2005, that the World Health Organisation (WHO) released a report highlighting the high burden of chronic diseases particularly in developing countries and the need for urgent action in the prevention and control of chronic diseases including chronic respiratory diseases (CitationWHO 2005). The reasons for this neglect are unclear. Several possible explanations can be offered.

These diseases have traditionally been stigmatized. It has been virtually impossible to mobilize either patients or society to address them as has been done for HIV/AIDS (Mawar et al 2006; CitationVanable et al 2006), cardiovascular diseases, or cancer (CitationChapple et al 2004). With conditions related to tobacco smoke exposure (lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) there has been a ‘blame the victim’ approach which promotes stigmatization (CitationBayer and Stuber 2006). In addition, the main burden of conditions such as tuberculosis and pneumonia in children are highly associated with poverty and inequity which in turn is fraught with a sense of ‘powerlessness’ which mitigates against social mobilization (CitationAnyangwe et al 2006).

Unlike cancer or cardiovascular diseases, the various respiratory conditions have been ‘partitioned’ to other ‘categories’ (even though they are generally managed within a single subspecialty of medicine) and are thus not ‘counted’ as a single entity, to be compared with other groups. Examples include lung cancer (counted as ‘cancer’), acute respiratory illnesses (especially pneumonia), and tuberculosis (often managed by lung specialists but ‘counted’ with infectious diseases).

Finally, these diseases (and especially chronic airflow limitation) can be ‘silent’. Even where there is extensive knowledge and expertise concerning them, they are frequently unrecognized. For example, if one reviews the medical records of a sample of patients on an adult medical ward in industrialized countries, the frequency with which chronic airflow limitation is mentioned in the clinical record is usually much less than the prevalence of the disease in the community; the frequency of the condition among hospitalized patients in a medical ward is most certainly substantially higher.

This article seeks to address the issue of chronic airflow limitation; a major contributor to the burden of chronic respiratory disease. It will focus on the situation in developing countries where the majority of the world’s population lives. It will outline what is known about the burden of disease and available interventions and will propose an approach to setting priority for action. For the purposes of this article, chronic airflow limitation refers to diseases that cause reduced pulmonary function related to disease of the airways and includes both fixed airflow limitation (as in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), bronchiectasis, and the sequelae of tuberculosis) and variable airflow limitation (as in asthma).

Burden of disease

Calculation of the burden of all respiratory diseases combined can be made from recent published reports (CitationLopez et al 2006) and indicates that respiratory diseases account for 15% of deaths in low-middle-income countries and 14% in high-income countries, second only to cardiovascular diseases which account for 21% and 27% respectively. Viewed in terms of premature deaths (years of life lost), this is even more dramatic: respiratory diseases account for 17%, compared with 15% for other communicable diseases and 14% for cardiovascular diseases. Among the respiratory diseases, lower respiratory tract infections account for the greatest proportion of years of life lost (48% of those due to respiratory diseases) with chronic airflow limitation accounting for a lower proportion (17%).

As part of an effort to prioritize health needs by quantifying the global burden of disease, health economists working in conjunction with the World Bank developed “Disability-Adjusted Life Years” (DALYs); a statistical measurement for account for both death and disability (World Bank 1993). From the World Health Report 2004 (CitationWHO 2004), the estimated DALYs lost due to all respiratory diseases in 2002 was 184 million (12% of the total) compared with 21% for other infectious and parasitic diseases, 13% for neuropsychiatric diseases, and 10% for cardiovascular diseases. Among the respiratory diseases, lower respiratory tract infections accounted for the greatest proportion (50%), with chronic airflow limitation accounting for 23%.

The prevalence of chronic airflow limitation is relatively high. The prevalence of asthma in adults (Table ) has been demonstrated between 1% and 10% with a median estimate around 2%–3% (CitationECRHS 1996). Among these cases, it is likely that a minority (less than 30%) have chronic airflow limitation (CitationAït-Khaled and Enarson 2005), yielding a community prevalence of asthma with chronic airflow limitation of 0.5 to 1.0%. The World Health Report 2004 estimates a range of COPD up to 1.7%, with the global median at just over 1.0%. These are in contrast to prevalence studies of COPD in the general population (confirmed by spirometry) among adults (Table ) in Europe, America, and Latin America (CitationMueller et al 1971; CitationGulsvik 1979; CitationLange et al 1989; CitationBakke et al 1991; CitationMarco-Jordan et al 1998; CitationMannino et al 2000; CitationViegi et al 2000; CitationVon Hertzen et al 2000; CitationMenezes et al 2005), where the prevalence varied from 4% to 27%. The PLATINO study (CitationMenezes et al 2005) describes the epidemiology of COPD in five major Latin American cities: Sao Paulo (Brazil), Santiago (Chile), Mexico City (Mexico), Montevideo (Uruguay), and Caracas (Venezuela). The same methodology was used and COPD defined as a ratio less than 0.7 of postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) divided by forced vital capacity (FVC). Crude rates of COPD ranged from 7.8% (95% CI 5.9–9.7) in Mexico City to 19.7% (95% CI 17.2–22.2) in Montevideo. After adjustment for key risk factors, the prevalence of COPD in Mexico City remained significantly lower than that in other cities. Altitude may explain part of the difference in prevalence. These results suggest that COPD is a greater health problem in Latin America than previously realised and suggests of a high prevalence of COPD in developing countries and particularly in middle income countries which are in similar epidemiologic transition (North and South Africa, Asia).

Table 1 Estimated prevalence of asthma symptoms

Table 2 Prevalence in general population of airway obstruction by spirometry (FEV1/FVC <70%)

The figures are based on very limited information. There are virtually no community-based surveys of the prevalence of chronic airflow limitation in low-income countries (such as the countries of Africa). More extensive information is available for asthma where the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (ISAAC) has led the way in providing comparative results from across the world (CitationBeasley et al 1998). However, this initiative providing a worldwide map of prevalence of asthma symptoms (Table ) has not yet provided results of lung function and is thus not able to give estimates of chronic airflow limitation among asthma patients. Moreover, its focus is children, which means that population estimates will under represent the situation. More recent initiatives, such as the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study, will hopefully improve our knowledge, however this very costly survey will be difficult to conduct in low and in the majority of middle countries. It is lamentable that information on a condition as widespread and as devastating as chronic airflow limitation is so lacking and underscores the point that these patients are greatly underserved.

Based on the available data, the combined community prevalence of airflow limitation due to the two conditions could be estimated in excess of 100 million persons (possibly substantially higher). Estimated DALYs lost in 2002 can be compared among regions (CitationWHO 2004). For comparative purposes and to illustrate the situation in low-income countries, those for Africa can be compared with the global estimates. DALYs lost due to all respiratory diseases were 14% for Africa compared with 12% globally. Among the respiratory diseases, lower respiratory tract infections accounted for a much greater proportion in Africa (68% compared with 50%), COPD accounted for just over 2% compared with 15% and asthma for just over 4% compared with 8% globally. Among patients seeking care in the health services of various developing countries implementing the “Practical Approach to Lung Health” asthma and COPD represent more than 1% of all consultations (Table ).

Table 3 Frequency of various conditions for which patients consulted health services in various countries implementing the Practical Approach to Lung Health

These estimates, however, must be viewed with extreme caution due to the severe limitation in data upon which they are based and the prevalence of chronic airflow limitation may be substantially higher than currently believed (as was the case in the studies in Latin America by CitationMenezes and colleagues [2005]). Nevertheless, even with the limited information available, we must conclude that chronic airflow limitation does account for a substantial burden of disease, even in the poorest countries where life expectancy is drastically lower and the effects of such chronic diseases would be expected to be consequently less. That so little attention is given to respiratory diseases in general, and to chronic airflow limitation in particular, in this setting is a travesty.

The financial consequences of chronic respiratory diseases are high and underscore the need for more investment on research and policy. The cost of asthma has increased in recent years in industrialised countries. For example, in 1998, asthma in USA (CitationWeiss and Sullivan 2001) accounted for an estimated US$12.7 billions annually (more than 2 times the estimated cost for 1990). Data on the direct (cost of health-care resources) and indirect (cost of the consequences of the disability) costs of COPD are also available only from industrialised countries. For example in 1993, the total annual economic burden of COPD in USA was estimated at US$23.9 billions (NHLB 1998). These data demonstrate that the total cost for COPD is greater than for other common respiratory disease such as asthma, influenza, pneumonia and tuberculosis.

Tobacco is the main etiological agent for chronic airflow limitation worldwide, although exposure to combustion products of biomass fuel is an important and underestimated risk factor in developing countries (CitationBaris and Ezzati 2004).

Interventions to improve prevention and management

During the last two decades, guidelines for standard case management of asthma and COPD have been adopted in most industrialized countries. They began with the Global Initiative of Asthma (GINA) (GINA 1995), updated in 2005. These guidelines recommend standardised management for asthma attacks and emphasize the crucial need of long-term treatment of asthma to alleviate disease severity, improve quality of life and to prevent exacerbations and attacks. Prevention aims to limit environmental factors that act as triggering factors (essentially allergens and tobacco). The technical measures proposed are based on the pathophysiology of asthma as a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways (explaining the need of regular use of inhaled steroids) that lead to recurrent episodes of symptoms linked to airflow obstruction (explaining the need of bronchodilators). The characteristic variability of airflow limitation in asthma highlights the importance of tools to measure and monitor lung function (spirometers and peak expiratory flow meters) to confirm the diagnosis and document the grade of severity. The following principles of GINA have been adopted in national guidelines, with regional or local adaptations:

Clear objectives for case management;

Diagnosis based on clinical history and lung function;

Classification of severity based on history and lung function;

Long-term treatment adapted to the severity grade;

Patient education and strong partnership with care providers to improve adherence to treatment and to promote self-management;

Routine follow-up for evaluation and adaptation of treatment.

Severity grade is determined by the level of airflow limitation after bronchodilator test demonstrating no, or incomplete (<15%), reversibility. The principles of case management are the following:

Diagnosis of air flow obstruction based on spirometry: FEV/FVC <70%;

Severity grade based on level of FEV1:

Stage 0: At risk – Normal spirometry; chronic symptoms (cough and sputum production).

Stage I: Mild COPD – FEV1/FVC < 70%, FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted and usually but not always chronic symptoms (cough, sputum production).

Stage II: Moderate COPD – FEV1/FVC < 70%, 50% ≤ FEV1 < 80% predicted and chronic symptoms (cough, sputum production) usually with shortness of breath.

Stage III: Severe COPD – FEV1/FVC < 70%, 30% ≤ FEV1 < 50% predicted and chronic symptoms (cough, sputum production, dyspnoea)

Stage IV : Very severe COPD – FEV1/FVC < 70%, FEV1 < 30% or FEV1 < 50% predicted plus chronic respiratory failure with clinical signs of right heart failure;

Secondary prevention is based on:

smoking cessation

avoidance of other exacerbating factors (indoor, work place pollution) and

influenza vaccination;

Stepwise treatment based on inhaled bronchodilators (short-acting beta 2 and/or anticholinergics) and long-acting beta agonists and inhaled steroids for moderate and severe cases with repeated exacerbations;

Rehabilitation;

Long term oxygen therapy for hypoxemia or heart failure.

Efficacy of interventions

Cochrane systematic reviews have confirmed both efficacy and safety of inhaled steroids in the management of asthma for adults and children (CitationAdams et al 2001, Citation2005a, Citation2005b). All inhaled steroids demonstrate a dose-response relationship for efficacy, but most of the benefit is in mild to moderate disease with low-moderate dose range of each drug. In patients with severe disease who are dependant of oral steroids, there may be a benefit in reducing oral steroids by using high-dose of inhaled steroids (CitationAdams and Jones 2006). Long-acting beta agonists provide additional improvement in lung function and in symptoms and could reduce the rate of exacerbations requiring oral steroids without additional serious adverse reactions (CitationNi Chroinin et al 2004, Citation2005).

Cochrane reviews of treatment of COPD have also been reported. Regular long-term use of ipratropium bromide, short-acting beta 2 agonist therapy or their combination show little benefit in stable COPD in improving lung function, symptoms, or exercise tolerance. Patients can choose the short-acting bronchodilator that gives the most improvement of their symptoms (CitationAppleton et al 2006). Long-acting beta agonists give small increases of FEV1 not associated with improvement in quality of life or reduction in breathlessness (CitationAppleton et al 2001). Long-acting anticholinergics reduce COPD exacerbations and hospitalizations.

Evaluation of effectiveness

The effectiveness of asthma guidelines has been demonstrated in several studies, in particular the Gaining Optimal Asthma Control (GOAL) study (CitationBateman et al 2004). The cost-effectiveness of inhaled steroids in management of persistent asthma has been consistently demonstrated, even in developing countries (CitationPerera 1995). The number of hospital days and emergency visits can be reduced by 50% to 80% for asthma patients requiring inhaled steroids. Substantial savings in healthcare costs have also been demonstrated (CitationPrice and Briggs 2002; CitationCastro et al 2003; CitationAdams et al 2001 CitationSchelledy et al 2005: CitationSimonella et al 2006).

Standard case management of COPD has been shown to improve the quality of life of patients and to decrease exacerbations and hospitalisations (CitationPaggiaro et al 1998; CitationFriedman et al 1999; CitationCalverley et al 2003a, Citation2003b; CitationOostenbrink.et al 2004), although long-term studies are lacking (CitationBarr et al 2005). Use of bronchodilators, steroids, and rehabilitation are recognized to be cost-effective (CitationRea et al 2004; CitationHalpin 2006) in industrialized countries. Management of COPD using the combination of all technical measures is usually costly (CitationWouters 2003; CitationOostenbrink and Rutten-van Molken 2004; CitationFournier et al 2005) and is not able to arrest, or decrease the progression in, the decline of lung function. A meta-analysis systematically conducted reviewed the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety on inhaled steroids in patient with COPD, and concluded that the risk-benefit ratio appears to favor inhaled steroids in patients with moderate to severe COPD (CitationGartlehner et al 2006), and has estimated that unplanned use of health services can be reduced by one-third. However, existing evidence does not indicate a treatment benefit for patients with mild COPD.

Relevance for developing countries

Most developing countries have no standard guidelines for assessing and managing chronic noncommunicable respiratory disease. Such services as exist in many low-income countries do not reach large parts of the population, particularly the poorest. A substantial proportion of this group of the population dies before age 40 (before they have the ‘possibility’ of developing chronic airflow limitation) and have limited or no access to health services. They represent 15% of the population in Latin America, 34% in the Middle East, and more than 40% in South-East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (CitationUNDP 1997). A clear priority must be to enhance access to health services in general if these patients are to benefit by the care they require.

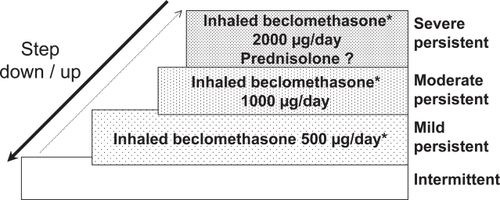

Some guidelines have been published for the management of COPD in developing countries. They include early recognition of disease by questionnaire, confirmation of diagnosis, and assessment of disease severity by clinical evaluation and spirometry (CitationSAPS 1998; CitationMHM and AMMMTS 1999). A standard case management approach for COPD for Asia and Africa has been proposed (CitationChan-Yeung et al 2004). The long term management recommended is a step-wise approach according to the disease severity (Figure ) using only inexpensive bronchodilatators: inhaled beta 2 short-action and/or inhaled ipratropium bromide with or without low dosage of slow release theophylline. Inhaled steroids are reserved for those where a clear response to a standardized trial of steroids has been demonstrated. Long-term oxygen therapy and rehabilitation programmes are usually not available in low-income countries.

Figure 1 Step-wise approach to treatment for COPD in developing countries.

Although the publication and distribution of international consensus reports are important advances, the benefits have not yet reached patients in many developing countries. Results achieved are not the same as in clinical trials, even in industrialized countries (CitationRabe et al 2000, Citation2004; CitationLai et al 2003; CitationNeffen et al 2005). Such guidelines are usually developed by professional societies and/or specialists and rarely involve service providers at the primary care level (CitationLalloo and Mclvor 2006). Additional bottlenecks in developing countries are: the low priority accorded to chronic diseases as compared with infectious diseases; lack of organization of follow-up; cultural barriers; poor education of health workers; lack of spirometry in low-income countries; and lack of access to, and the high cost of necessary drugs (CitationSterk et al 1999; CitationEnarson and Aït-Khaled 1999; CitationAït-Khaled et al 2000; CitationGelders et al 2006; CitationWan and Aït-Khaled 2006).

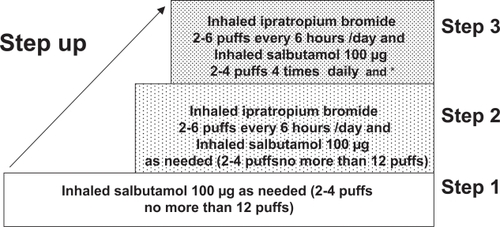

The Union Asthma guide published in 1996 and revised in 2005 (CitationAït-Khaled and Enarson 2005) proposes a technical package for asthma management, implemented within general health services, and appropriate for services where resources are extremely limited. The standard case management approach recommends the use of two drugs, both of which are included in the WHO essential drugs list: inhaled beclomethasone 250 μg/puff and inhaled salbutamol 100 μg/puff (Figure ). A standardized information system is recommended, including a patient register in which each new patient with persistent asthma is registered, with information on initial status and follow-up. Routine analysis of case notification and of outcome of management is based on the register. Evaluation of this approach in several low- and middle-income countries demonstrated its feasibility (CitationAït-Khaled et al 2006a) and its efficiency estimated after one year of follow-up (CitationAït-Khaled et al 2006b). Despite a high proportion of patients (31%) who did not continue treatment for at least one year, 51% of patients in the cohort had a decrease in their severity of disease (CitationAït-Khaled et al 2006b); emergency visits and hospitalizations were dramatically reduced with substantial cost-saving to the health services.

Setting priorities for management of chronic airflow limitation

In developing countries, the objective of chronic respiratory disease prevention and management is to decrease the burden of illness, prevent avoidable deaths, and increase the quality of life of patients. This is achieved by adaptation of international guidelines to the particular context of developing countries. Such efforts have as objectives to (CitationAït-Khaled et al 2001, Citation2002; CitationBousquet et al 2003):

Reduce tobacco smoking in the whole population;

Encourage smoking cessation for patients who access services;

Improve quality of services by standard case management;

Promote cost-effective approaches to treatment;

Enhance access to affordable essential medications;

Avoid ineffective and costly services.

This problem requires firm political action directed to endorsing and implementing the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and, particularly, to increase legislation to reduce tobacco consumption (CitationWHO 1999). Secondary prevention is essential. This includes smoking cessation programmes, the simplest and most appropriate of which is an intervention called ‘brief advice’ (CitationSlama et al 1995; CitationSlama 1998; CitationFiore et al 2000). In many countries, efforts to reduce the effects of exposure to combustion products of biomass fuel are important (CitationBaris and Ezzati 2004). For COPD, a number of interventions are not justifiable and should not be used, including periodic courses of antibiotics, long-term oral steroids, and mucolytics.

For asthma, a Cochrane review concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support initiating therapy with a combination of inhaled glucocorticoids and long-acting beta2-agonist rather than inhaled glucocorticoids alone as first line therapy for persistent asthma in steroid-naïve adults (CitationNi Chroinin et al 2004). Costly investigations not recommended for use in developing countries include allergy skin tests, measurement of total and specific IGE, and nonspecific bronchial challenge. Immunotherapy is not recommended in low income countries (CitationSterk et al 1999; CitationBousquet et al 2001) because, in addition to its very high cost and limited indications, many allergens are not well identified in these developing countries, and rare side effects might be severe.

International guidelines for management of COPD may be very difficult to implement in low-income countries as they require redirecting existing resources from other priority activities. This may be possible in some middle-income countries where the resources are greater and quality of services better and in some particular settings in low income countries (private hospitals or universities).

As resources are not limitless, it remains for governments to choose some interventions over others. To make these choices, a set of criteria has been proposed by the WHO, in collaboration with the Public Health Agency of Canada. In acknowledging the growing problem of chronic diseases in developing countries and its relative neglect, they have recommended the following definition of categories of cost-effectiveness (CitationWHO 2005):

Very cost-effective: interventions that avert each DALY at a cost less than gross domestic product per head;

Cost-effective: interventions that avert each DALY at a cost between one and three times gross domestic product per head;

Not cost-effective: interventions that avert each DALY at a cost higher than three times gross domestic product per head.

International responses

WHO has responded to the needs in two ways. A comprehensive integrated package for the standardized management for respiratory disease, Practical Approach to Lung health (PAL) (CitationOttmani et al 2005), has been developed and implemented in several developing countries. More recently a new WHO initiative, Global Alliance for Respiratory Chronic Diseases (GARD), has been launched. The Union contributes to these initiatives through:

Creation of an Asthma Drug Facility to improve availability and affordability of essential asthma drugs (CitationAït-Khaled 2006; CitationBillo 2004, Citation2006)

Implementation of an integrated package for improvement of quality of care at the first level of referral in developing countries. (CitationEnarson 1998)

References

- AdamsRJFuhlbriggeAFinkenelsteinJA2001Impact of inhaled anti-inflammatory therapy on hospitalisations and emergency department visits for children with asthmaPediatrics1077061111335748

- AdamsNPBestallJBMaloufR2005aBeclomethasone versus placebo for chronic asthmaCochrane Database Syst Rev1CD00273815674896

- AdamsNPBestallJMLassersonTJ2005bFluticasone versus beclomethasone or budesonide for chronic asthma in adults and childrenCochrane Database Syst Rev2CD002310

- AdamsNPJonesPW2006The dos-response characteristics of inhaled corticosteroids when used to treat asthma: An overview of Cochrane systematic reviewsRespir Med100129730616806876

- Aït-KhaledNAureganGBencharifN2000Affordability of inhaled corticosteroids as a potential barrier to treatment of asthma in some developing countriesInt J Tuberc Lung Dis42687110751075

- Aït-KhaledNEnarsonDABousquetJ2001Chronic respiratory diseases in developing countries: the burden and strategies for prevention and managementBull World Health Organ79971911693980

- Ait- KhaledNChauletPEnarsonDA2002Clinical management of clinical obstructive pulmonary diseaseSimilowskiTDerennePEpidemiology and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in AfricaNew YorkMarcel Dekker43100730

- Aït-KhaledNEnarsonDA2005Management of asthmaA guide to the essentials of good clinical practice2nd edParis, FranceInternational Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung DiseaseURL: http//:www.iuatld.org

- Aït-KhaledNEnarsonDABencharifN2006aImplementation of asthma guidelines in health centres of several developing countriesInt J Tuberc Lung Dis101049

- Aït-KhaledN2006Favoriser l’accessibilité aux médicaments essentiels de l’asthmeRev Mal Resp2310S7610S79

- Aït-KhaledNEnarsonDABencharifN2006bTreatment outcome of asthma after one year follow-up in health centres of several developing countriesInt J Tuberc Lung Dis1091116

- AmosA1996Women and smoking: a global issueWorld Health Stat Q4912733

- AnyangweSCMtongaCChirwaB2006Health inequities, environmental insecurity and the attainments of the millennium development goals in sub-Saharan Africa: The case study of ZambiaInt J Environ Res Public Health32172716968967

- AppletonSPoolePSmithB2001Long-acting beta2-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with poorly reversible airflow limitationCochrane Database Syst Rev4CD001104

- AppletonSJonesTPooleP2006Ipratropium bromide versus short acting beta-2 agonists for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev2CD00138716625543

- BarrRGBourbeauJCamargoCA2005Tiotropium for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev2CD00287615846642

- BayerRStuberJ2006Tobacco control, stigma, and public health : rethinking the relationsAm J Public Health96475016317199

- BeasleyRKeilUVon MutiusEISAAC Steering Committee1998Worldwide variation in the prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinoconjonctivitis and atopic eczema symptoms: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC)Lancet3511225329643741

- BakkeSBasteVHanoaR1991Prevalence of obstructive lung disease in a general population: relation to occupational title and exposure to some airborne agentsThorax46863701792631

- BarisEEzzatiM2004Should interventions to reduce respirable pollutants be linked to tuberculosis control programmes?BMJ3291090315528622

- BatemanEDBousheyHABousquetJGOAL Investigators Group2004Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma Control StudyAm J Respir Crit Care Med1708364415256389

- BilloN2004Do we need an asthma drug facility?Int J Tuberc Lung Dis839115141728

- BilloN2006ADF from concept to realityInt J Tuber Lung Dis10709

- BousquetJNdiayeMAït-KhaledN2003Management of chronic respiratory and allergic diseases in developing countries. Focus on sub-Saharan AfricaAllergy582658312708972

- BousquetJVan CauwenbergPKhaltaevN2001ARIA workshop report in collaboration with WHOJ Allergy Clin Immunol1085 SupplS14733411707753

- CalverleyPMPauwelsRVestboJTrial of Inhaled steroids and long acting beta 2 agonists. study group2003aCombined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trialLancet3614495612583942

- CalverleyPMBoonsawatWCsekeZ2003bMaintenance therapy with budesonide and fomoterol in chronic obstructive diseaseEur Respir J229121914680078

- CastroMZimmermanNACrockerS2003Asthma intervention program prevents readmissions in high healthcare usersAm J Respir Crit Care16810959

- Chan-YeungMAït-KhaledNWhiteN2004Management of COPD in Asia and AfricaInt Union Tuberc Lung Dis815970

- ChappleAZieblandSMcPhersonA2004Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: qualitative studyBMJ328147015194599

- EnarsonDAAït-KhaledN1999Cultural barriers to asthma managementPediatr Pulmonol2829730010497379

- EnarsonDA1998Lung health and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung DiseaseInt J Tuberc Lung Dis2969709869109

- [ECRHS] European Community Respiratory Health Survey1996Variations in the prevalence of respiratory symptoms, self-reported asthma attacks, and use of asthma medications in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS)Eur Respir J9687958726932

- FioreMCBaileyWCCohenSJ2000Treating tobacco use and dependance Clinical Practice GuidelineRockville, MDU.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- FriedmanMSerbyCWHillemanDE1999Pharmacoeconomic Evaluation of a combination of Ipratropium Plus Albuterol Compared With Ipratropium and albuterol alone in COPDChest1156354110084468

- FournierMTonnelABHoussetB2005Economic burden of COPD in France: The Scope Study [French]Rev Mal Respir222475516092163

- GartlehnerGHansenRACarsonSS2006Efficacy and safety of inhaled corticosteroids in patients with COPD. A systematic review and meta-analysis of health outcomesAnn Fam Med42536216735528

- GeldersSEwenMNoguchiN2006Price, availability and affordability. An international comparison of chronic disease medicines [online]. Accessed on February 2, 2007. Geneva: WHO, Health Action International. URL: http://mednet3.who.int/medprices/CHRONIC.pdf

- [GINA] Global Initiative for Asthma2005Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. NHLBI/WHO workshop report [online]. Accessed on February 2, 2007. NIH publication number 95–3659. Revision 2005. URL: http://www.gina.com/

- [GOLD] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease2005Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [online]. Accessed on February 2, 2007. NIH, NHLBI publication Number 2701, April 2001. Updated 2005. URL: http://www.goldcopd.org/

- GulsvikA1979Prevalence and manifestations of obstructive lung disease in the city of OsloScand J Respir Dis6028696524075

- HalpinDM2006Heath economics of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseProc Am Thorac322733

- LaiCKWDe GuiaTSKimYY2003Asthma control in Asia-Pacific StudyJ Allergy Clin Immunol11126312589343

- LallooUGMclvorRA2006Management of chronic asthma in adults in diverse regions of the worldInt Union Tuberc Lung Dis1047483

- LangePGrothSNyboeJ1989Chronic obstructive lung disease in Copenhagen: cross-sectional, epidemiological aspectsJ Intern Med22625322787829

- LopezADMathersCDEzzatiM2006Global and regional burden of diseases and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health dataLancet36717475716731270

- ManninoDMGagnonRCPettyTL2000Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994Arch Intern Med1601683910847262

- Marco-JordanLMartin-BerraJInigoMC1998Enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva cronica en la poblacion general: estudio epidemiologico realizado en GuipuzcoaArch Bronconeumol342379580182

- MawarNSahaSPanditA2005The third phase of HIV pandemic: social consequences of HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination and future needsIndian J Med Resp12247184

- MenezesAMPerez-PadillaRJardimJB2005Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence studyLancet36618758116310554

- [MHM and AMMMTS] Ministry of Health of Malaysia, Academy of Medicine of Malaysia and Malaysian Thoracic Society1999Guidelines in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A consensus statementMed J Malaysia5438740111045071

- MuellerREKebleDLPlummerJ1971The prevalence of chronic bronchitis, chronic airway obstruction, and respiratory symptoms in a Colorado cityAm Rev Respir Dis103209285100088

- [MHLBI] National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute1998Morbidity and mortality: 1998 Chartbook on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseasesBethesda MDUS Department, of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health

- NeffenHFritsherCSchachtFCAIRLA Survey Group2005Asthma control in Latin America: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Latin America (AIRLA) surveyRev Panam Salud Publica17191715826399

- Ni ChroininMGreenstoneIRDucharmeFM2004Addition of inhaled long-acting beta2-agonists to inhaled steroids as first line therapy for persistent asthma in steroid-naive adultsCochrane Database Syst Rev4CD005307

- Ni ChroininMGreenstoneIRDanishA2005Long-acting beta2-agonists versus placebo in addition to inhaled corticosteroids in children and adults with chronic asthmaCochrane Database Syst Rev4CD00553516235410

- OostenbrinkJBRutten-van MölkenMPNoordJA2004One-year cost-effectiveness of tiotropium versus ipratropium to treat chronic obstructive pulmonay diseaseEur Respir J23241914979498

- OostenbrinkJBRutten-van MolkenMP2004Resource use and risks factors in high-cost exacerbations of COPDRespir Med9898839115338802

- OttmaniSESherpbierRPioA2005Practical Approach to Lung Health (PAL): A primary health care strategy for the integrated management of respiratory conditions in people five years of age and overGenevaWorld Health OrganizationWHO/HTM/TB/2005.351.

- PaggiaroPLDahleRBakranI1998Multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial of inhaled fluticasone in patients with COPD. International COPD study groupLancet14773809519948

- PereraBJ1995Efficacy and cost effectiveness of inhaled steroids in asthma in developing countriesArch Dis Child72312167763062

- PriceMJBriggsAH2002Development of an economic model to assess the cost effectiveness of asthma management strategiesPharmaconeconomics2018394

- RabeKFVermeirePASorianoJB2000Clinical management of asthma in 1999: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Europe (AIRE) studyEur Respir J1680211153575

- RabeKFAdachiMLaiCKW2004Worldwide severity and control of asthma in children and adults: the Global Asthma Insights and Reality SurveysJ Allergy Clin Immunol11440715241342

- ReaHMcAuleySStewartA2004A chronic disease management programme can reduce days hospital for patients with COPDIntern Med J346081415546454

- [SAPS] Working Group of the South African Pulmonary Society1998Guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseSouth African Med J888

- SchelledyDCMcCormickSRLeGrandTS2005The effect of a pediatric asthma management program provided by respiratory therapists and patient outcomes and costsHeart Lung34423816324962

- SimonellaLMarksGSandersonK2006Cost-effectiveness of current and optimal treatment for adult asthmaIntern Med J3624416640742

- SlamaKKarsentySHirschA1995Effectiveness of minimal intervention by general practitioners with their smoking patients: a randomised, controlled trial in FranceTob Control41629

- SlamaK1998Tobacco control and prevention. A guide for low income countries. Paris: International Union against Tuberculosis and. Lung Disease. URL at http://www.iuatld.org/

- SterkPJBuistSAWoolcockAJMarksGB1999The message from the 1998 World Asthma MeetingEur Respir J1414355310624779

- [UNDP] United Nations Development Programme1997Human development report 1997. Human development to eradicate poverty [French]ParisEditions Economica

- VanablePACareyMPBlairDC2006Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and womenAIDS Behav104738216604295

- ViegiGPedreschiMPistelliF2000Prevalence of airways obstruction in a general population: European Respiratory Society vs American Thoracic Society definitionChest1175 Suppl 2339S45S10843974

- Von HertzenLReunanenAImpivaaraO2000Airway obstruction in relation to symptoms in chronic respiratory disease—a nationally representative population studyRespir Med943566310845434

- WanAït-KhaledN2006Dissemination and implementation of Asthma Guidelines. State of the ArtInter J Tuberc Lung Dis1071016

- WeissKBSullivanSD2001The health economics of asthma and rhinitis. Assessing the economic impactJ Allergy Clin Immunol1073811149982

- World Bank1993World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health. World Bank Publication.

- [WHO] World Health Organization1999Framework convention on tobacco control. Technical Briefing Series. WHO/NCD/TF1/99.1–7

- [WHO] World Health Organization2004The World Health Report 2004: changing history. Statistical Annex 127–131GenevaWorld Health Organization

- [WHO] World Health Organization2005Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment [online]GenevaWorld Health Organization Accessed on November 8, 2006. URL: http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/contents/en/index.html

- WoutersEF2003Economic analysis of the confronting COPD survey: an overview of resultsRespir Med97suppl CS31412647938

- YachD1996Le tabac en AfriqueForum Mondial de la Santé17308