Abstract

Although medical treatment of COPD has advanced, nonadherence to medication regimens poses a significant barrier to optimal management. Underuse, overuse, and improper use continue to be the most common causes of poor adherence to therapy. An average of 40%–60% of patients with COPD adheres to the prescribed regimen and only 1 out of 10 patients with a metered dose inhaler performs all essential steps correctly. Adherence to therapy is multifactorial and involves both the patient and the primary care provider. The effect of patient instruction on inhaler adherence and rescue medication utilization in patients with COPD does not seem to parallel the good results reported in patients with asthma. While use of a combined inhaler may facilitate adherence to medications and improve efficacy, pharmacoeconomic factors may influence patient’s selection of both the device and the regimen. Patient’s health beliefs, experiences, and behaviors play a significant role in adherence to pharmacological therapy. This manuscript reviews important aspects associated with medication adherence in patients with COPD and identifies some predictors of poor adherence.

Introduction to management issues in COPD

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, currently 210 million people have COPD and 3 million people died of COPD in 2005. The WHO predicts that COPD will become the fourth leading cause of death worldwide by 2030 (CitationCOPD 2007). The burden of COPD assessed by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) ranks 10th worldwide (CitationWHO 2008). Total deaths from COPD are projected to increase by more than 30% in the next 10 years unless urgent preventive measures are in place (CitationCOPD 2007).

Although COPD cannot be cured, optimal management provides symptom control, slows progression of the disease, and may improve the quality of life (CitationKaplan and Ries 2005; CitationRodriguez-Roisin 2005). Management of COPD becomes suboptimal when physicians fail to prescribe appropriate therapies, due to poor adherence to evidence-based guidelines and underdiagnosis (CitationSnider 1985; Foster et al 2007), or when patients fail to adhere to prescribed treatment regimens. There are a limited number of studies on the physician knowledge and practice patterns for individuals with COPD that may result in suboptimal management and adversely affect patient outcomes (CitationRamsey 2000; CitationGeorge et al 2005; Foster et al 2007; Sestini et al 2007).

Adherence is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behavior (in terms of taking medications, following diets, or executing lifestyle changes) coincides with medical or health advice” (CitationHaynes et al 1979). Adherence to medication regimens is often suboptimal when patients are on long-term pharmacotherapy using repeat prescriptions. A study published by the WHO estimated 50% adherence or less for patients on long-term pharmacotherapy (CitationWHO 2003).

Adhering to inhaled medications is of paramount importance in the management of patients with COPD in both clinical and ambulatory settings. These pharmacologic agents include bronchodilators and corticosteroids used in a variety of aerosol devices that include small volume nebulizers (SVNs), pressurized metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs), and dry powder inhalers (DPIs). Selection of the medication and the device typically depends on the efficacy of the different inhaled medications and the devices. However, this selection is often limited by the availability of a match between the medication prescribed and the aerosol device. While it is desirable that the medications prescribed to a patient are delivered through the same or similar devices, adherence to the right medication – device combination may be influenced by commercial availability. The medication – device availability problem will be compounded by the phasing-out of CFC-propelled pMDIs at the end of 2009 as proposed by the Federal register ruling (CitationFDA 2007). Replacement of CFC-propelled pMDIs by hydrofluoroalkane (HFA)-propelled pMDIs has been more difficult than expected since it has resulted in a redesign of the entire pMDI metering-valve system at a higher cost than simply replacing the propellant. This transitioning will initially restrict the list of available agents and could have considerable financial implications in the routine management of patients with COPD (CitationRau 2005; CitationSmyth 2005).

Medication regimens for patients with COPD are particularly vulnerable to adherence problems because of the chronic nature of the disease, the use of multiple medications or polypharmacy, and the periods of symptom remission. Patients with COPD are often prescribed aerosolized medications to use from 2 to 6 times daily plus concurrent therapy for other comorbidities that may include diabetes, hypertension, and coronary artery disease (CitationKrigsman et al 2007a; CitationSteinman et al 2006).

Despite the efforts of the global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) to provide clinicians with the best therapeutic guidance, adherence to pharmacologic therapy among patients with COPD has been historically poor (CitationWindsor et al 1980; CitationKaplan et al 1990; CitationDolce et al 1991; CitationGeorge et al 2005; CitationKrigsman et al 2007b, Citationc). Patients with COPD display significantly lower adherence to treatment than asthmatic patients (CitationJames et al 1985; CitationCochrane 1992; CitationHaupt et al 2008). Several studies have reported that an average of 60% of patients with COPD do not adhere to prescribed therapy (CitationChryssidis et al 1981; CitationTaylor et al 1984; CitationDompeling et al 1992; CitationBosley et al 1994; CitationKrigsman et al 2007b, Citationc; CitationHaupt et al 2008) and that up to 85% of patients use their inhaler ineffectively (CitationCrompton 1990; CitationThompson et al 1994; CitationVan Beerendonk et al 1998; Citationvan der Palen et al 1995, Citation1998; CitationHesselink et al 2001; CitationSerra-Batlles et al 2002). British and Swedish studies indicate that 10%–20% of repeat prescriptions never reach a pharmacy (CitationRashid 1982; CitationNilsson et al 1995).

Adherence to therapy in COPD is complex. Patients with COPD require adequate education on the disease process, comorbidities, and also on the use of different medications and devices (CitationChryssidis et al 1981; CitationDolce et al 1991). They often need to make important behavioral and lifestyle changes such as starting a smoking cessation program, adhering to an exercise program, and wearing oxygen.

Several methods are used to measure adherence: refill adherence based on pharmacy records of dispensed prescription or manual recording of collected prescriptions, and self-reports of compliance using medication adherence report scales (MARS) (CitationGeorge et al 2005). Although adherence should ideally be measured upon ingestion or administration of the medication, this is not practical for large groups. Most studies rely on a mixture of refill adherence and self-report. Since the most commonly used method to measure is the self-report (CitationFarmer 1999) this review focuses only on this technique.

Numerous factors predispose patients with COPD to poor adherence. Recognition of the type of nonadherence in patients with COPD must be the first step in this complicated process of improving adherence. Prescription of an inhaled medication requires knowledge of different groups of medications and the potential clinical efficacy of combinations. It also requires being familiar with several aerosol delivery devices. Newer medications and devices improve clinical outcomes and ease of use but typically mean a higher out-of-pocket expense for patients. Patient’s perceptions of their illness, their understanding of the treatment, and their relationship with the primary care provider are critical to adherence to therapy. It is the aim of this manuscript is to review some of these important aspects affecting adherence to medication and to identify some predictors of poor adherence in patients with COPD.

Underuse, overuse, and improper use

There are three classic types of nonadherence to therapy: underuse, overuse, and improper use. Underuse is defined as a reduction of the apparent daily use versus a standard dose of a medication that is indicated for the treatment or prevention of a disease or condition (CitationLipton et al 1992; CitationHarrow et al 1997). Improper use or inappropriate use is confirmed by determining whether a drug is ineffective, not indicated, or if there is unnecessary duplication of therapy (CitationSteinman et al 2006).

Although these three factors have been well defined in the literature, there is limited evidence that links specific factors to each form of nonadherence in patients with COPD. The most common type of nonadherence in patients with COPD is underuse (CitationHarrow et al 1997; CitationGeorge et al 2005). By contrast, improper use is the most frequent type of nonadherence in patients older than 65 years with polypharmacy (taking 2 or more medications) (CitationSteinman et al 2006). Factors with tendency for association with unnecessary drug use include white race, income <US$30,000/year, more than 6.8 (±2) of prescription medications, and lack of patient’s health belief (Rossi et al 2007). In older adults, higher levels of independence and self-reliance have been associated with lower adherence to a medication regimen (CitationInsel et al 2006). The two most common reasons for a medication to be considered inappropriate are lack of effectiveness and lack of indication (CitationHajjar et al 2005; CitationSteinman et al 2006; Rossi et al 2007). Inhaled medications are not on the top 5 medications that are inappropriately used in patients older than 65 years (CitationHajjar et al 2005; Rossi et al 2007).

In patients with COPD, underuse is followed in frequency by overuse and improper use of the medication delivering device. Underuse could be sporadic or systematic. From forgetting an occasional dose to changing dosing schedule, patients with underuse are at a higher risk for adherence-related morbidity. A recent evaluation of the use of ICS in primary care patients revealed that up to 30% of the patients did not have a clear indication for this medication (CitationLucas et al 2008). Although improper use and underuse often coexist in the same patient, improper use may not correlate with underuse (CitationSteinman et al 2006).

There is evidence of overuse of short-acting beta agonists in patients with asthma (Lynd et al 2002), but little is known about the real incidence of overuse in patients with COPD. During respiratory distress, approximately half of the patients report using more than the prescribed amount of medications (CitationDolce et al 1991; CitationBosley et al 1994).

Clinical efficacy of major classes of medications and combinations

Determination of clinical efficacy involves evaluation of outcomes such as lung function, rate of exacerbations, and mortality. However, these outcome parameters need to be a reflection of the clinical efficacy perceived by the patient. A combination of objective and subjective clinical efficacy is a critical determinant of adherence to therapy. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), long-acting β2-agonists (LABAs), and anticholinergics have been recommended for the treatment of COPD. LABAs are recommended by GOLD (GOLD 2007) when patients continue to experience problems on short-acting bronchodilators (SABAs). The most obvious benefit of combination therapy is in terms of patient convenience that may lead to greater treatment adherence.

Lung function

Current evidence indicates that there is statistically significant difference in FEV1 and in health status measurements in favor of LABAs (CitationAppleton et al 2006) and ICS (CitationYang et al 2007). Several randomized controlled trials have found that a LABA – ICS combination therapy is associated with a significant increase over the baseline FEV1 when compared with the groups receiving placebo, LABA alone, or ICS alone (CitationCalverley et al 2007; CitationNannini et al 2007a). Addition of tiotropium to the LABA – ICS combination significantly improves lung function (CitationAaron et al 2007). The combination of ipratropium bromide and albuterol in patients with COPD results in significant improvement in peak FEV1 compared with albuterol or ipratropium alone (CitationGross et al 1998). CitationTashkin et al (2007) reported no significant difference in lung function measured by FEV1 in a group of patients with COPD randomized to SVN, pMDI, and concomitant treatment involving SVN (morning and night) plus pMDI (afternoon and evening) using a combination of albuterol and ipratropium bromide.

Rate of exacerbations, hospitalizations, and mortality

Using LABA – ICS is associated with a significant reduction in the rate of exacerbation, admission rates, and mortality (CitationAaron et al 2007; CitationCalverley et al 2007; CitationNannini et al 2007b, Citation7c). Combination therapy may reduce 1 exacerbation of COPD every 2–4 years (CitationCalverley et al 2007). Patients with COPD at any stage may perceive the lower health resource utilization as a motivator to adhere more rigorously to medications. However, this correlation has not been determined. Trials of short-acting anticholinergic and SABA combinations have shown a significant reduction in exacerbations compared with monotherapy, but no difference in mortality (CitationSin et al 2003).

Use of rescue medication

The use of rescue medications during COPD exacerbations may seem to be the most feasible explanation for overuse. During an exacerbation, an average of 1 additional puff during the day and half a puff during the night is seen two weeks prior and after an exacerbation regardless of COPD stage (CitationCalverley et al 2005). However, changes in rescue medication intake poorly correlate with exacerbations (CitationCalverley et al 2005). The use of LABA – ICS has been associated with a significant reduction in mean puffs per day of SABA (CitationMahler et al 2002; CitationHanania et al 2003), significant increases in the percentage of nights with no awakenings requiring SABA versus placebo, and a significant difference in median percentage of days without use of relief medication (CitationCalverley et al 2003a, Citationb; CitationSzafranski et al 2003).

Safety and tolerability of major classes of medications and combinations

Adverse events to medications are reported by 90% of the patients with COPD (CitationCalverley et al 2007). The presence of serious side effects negatively affects adherence. An increase in the risk of pneumonia in patients with COPD using a combination of ICS and LABA has been reported in several studies (CitationCalverley et al 2007; CitationNannini et al 2007b). The most frequently reported adverse event was an exacerbation of COPD. Although there is no significant difference in the occurrence of overall reported adverse events between LABA – ICS and placebo, pneumonia, candidiasis, nasopharyngitis, hoarseness, and upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) occurred more frequently when treated with a LABA – ICS combination () (CitationNannini et al 2007a).

Table 1 Most common adverse effects with combination therapy

Adherence to individual medications and combinations

Type of medication

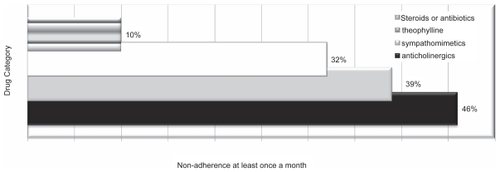

Patients with COPD have the lowest adherence to a regimen that included inhaled anticholinergic agents followed in order by the inhaled sympathomimetics, theophylline, corticosteroids, and antibiotics (CitationDolce et al 1991) ().

The ability to produce quick relief of symptoms or the safety profiles could explain class differences. It has been suggested that compliance to corticosteroids should be lower than to bronchodilators, because of the lack of direct symptom-relieving effect of the corticosteroids. However, patients may adhere to regimens that include oral corticosteroids and antibiotics more frequently because these medications are typically prescribed for short periods of time. Since they are prescribed to deal with acute symptoms, the patients’ perception is that these medications are more urgent and necessary.

Complexity of medication regimens

It has been previously reported that overall, the average number of time-contingent and as needed (P.R.N.) medications per patient may be as high as 6.26 (range, 1–16) (CitationDolce et al 1991). Up to 77% of patients with COPD may receive 2 or more oral-contingent medications (CitationDolce et al 1991). One-third typically receive 2 or more inhaled time-contingent medications, 45% receive 1 inhaled time-contingent medication, and 23% receive no inhaled time-contingent medications (CitationDolce et al 1991). The average of prescribed oral time-contingent and inhaled time-contingent medications are 3.53 and 1.17, respectively. Thirty percent of patients with COPD are prescribed oral P.R.N. medications and 17% had inhaled P.R.N. medications (CitationDolce et al 1991). Many of these medications have different dosing schedules. Thus, it is quite common for patients to be prescribed a combination of 5–8 oral and inhaled medications, with many medications requiring different dosing patterns.

Use of ipratropium bromide and albuterol in one inhaler is associated with a significantly lower risk of an emergency department visit or hospitalization, lower mean monthly health charges, shorter hospital stays, and greater likelihood of compliance than if used in two separate inhalers (CitationChrischilles et al 2002).

Selection of the aerosol delivery device

All aerosol delivery devices have relative advantages and disadvantages, as well as a potential to affect outcomes. The marketing of a myriad of aerosol delivery devices has resulted in a confusing number of choices for clinicians and patients. Although the fundamental principle of prescribing is based on the use of the most clinical and cost-effective medication and device, choices may become influenced by factors that are not clinically relevant or evidence-based. The ability of the patient to use the prescribed device affects adherence to treatment.

Clinical efficacy

The overall conclusion of numerous studies demonstrates that there is no evidence to support clinically important differences between aerosol devices. A systematic review (CitationDolovich et al 2005) identified 394 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing inhaled corticosteroid, β2-agonist, and anticholinergic agents that were delivered by pMDI, pMDI with spacer/holding chamber, nebulizer, or DPI. None of the pooled meta-analyses found a significant difference between devices in any efficacy outcome of patients with asthma and COPD in the outpatient and hospital acute care settings. A recent clinical trial (CitationTashkin et al 2007) reported no appreciable changes from baseline or pair wise differences between SVN and pMDI treatment arms at weeks 6 or 12 in peak flow measurements and symptom scores of patients with COPD.

In all the pooled meta-analyses, each of the delivery devices has provided similar outcomes in patients using the correct technique for inhalation. However, clinical benefit also depends on the ability of the patients to use the device and on their adherence. Real-life observational studies that evaluated patient inhalation techniques have shown frequent improper use of pMDIs and DPIs that may result in significant clinical differences between devices.

Patient acceptability and preference

Elderly patients with COPD show a preference for the SVN with regard to effectiveness and in favor of the pMDI with regard to acceptability (CitationBalzano et al 2000). SVN treatment is often prescribed to patients who prefer SVNs or demonstrate poor coordination with either a pMDI or DPI. Because SVNs are not as portable as pMDIs or DPIs, ambulatory patients find pMDIs and DPIs more convenient for use when they are away from home.

Inhalers and dosing technique

Although patients may adhere to the dosing schedule, they may use the inhaler improperly (CitationMcFadden 1986). Inhaler specific design features also contribute significantly to the patient’s adherence to treatment (CitationBrown et al 1992; CitationWoodman et al 1993; Citationvan der Palen et al 1994). Patient technique is a process that encompasses an individual’s previous experiences, education, abilities, and the teaching received on the specific device. These factors may interact to various degrees with the different types of inhaler devices to influence eventual technique and adherence. The typical method to evaluate inhaler technique is by assigning a score on the number of steps performed correctly out of the total number of possible steps. An evaluation of inhaler use in 316 patients suffering from asthma or COPD found that 89% of the patients made at least one mistake in the inhalation technique (Citationvan Beerendonk et al 1998). The most common skill error was “not continuing to inhale slowly after actuation of the inhaler” (69.6%). The nonskill item most patients had difficulties with was “exhaling before the inhalation” (65.8%). Patients who used a pMDI made significantly fewer nonskill mistakes than patients using a DPI (Citationvan Beerendonk et al 1998). A systematic review (CitationBrocklebank and Ram 2001) using the outcome of “ideal” inhaler technique showed that the percentage of patients with all steps correct was 43% for pMDI alone, 55% for pMDI + spacer, and 59% for DPI. There was statistical difference between pMDI alone and DPI or pMDI + spacer, but whether this is clinically significant is difficult to judge, particularly if cost efficacy is considered. The data support the conclusion of many reports that pMDI devices are poorly used.

When the pMDI is used, more than 50% of subjects may perform ≤5 out of 9 steps correctly and only about 11% of the subjects could perform all steps correctly (CitationLuk et al 2006) (see ).

Table 2 Steps for correct use of the inhaler

The most frequent problem is failure to coordinate actuation with inhalation and to hold their breath after inhalation. When patients are asked simple questions to establish if they have a basic understanding of their nebulized medication (eg, do you know what medications you use? how often? do you know if the medication you take has a bronchodilatory or anti-inflammatory effect?), 52% of patients are not able to answer these questions correctly; although 91% believe that they do understand the treatment they were prescribed. Of those who are unable to answer correctly, 60% are nonadherent (CitationBosley et al 1996). To complicate matters, primary care physicians are not familiar with relevant features of currently available inhalers (Sestini et al 2007).

Patient preference – ease of use

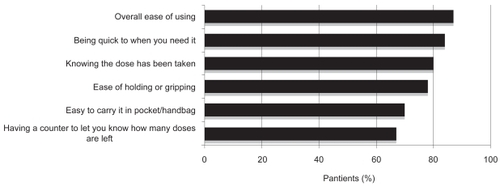

In a recent comparison of the Diskus® inhaler (DK) and the Handihaler® (HH) regarding preference and ease of use, although there was no difference in the number of instructions needed for both inhalers, more patients preferred the DK. The most important general items for patients were hygiene and a clear instruction leaflet (Citationvan der Palen et al 2007). Of the inhaler-specific aspects, more than 90% of patients find ease of use in general, ability to take the medication quickly, ease of use during an exacerbation, the feel in the hand, and ease of the cap important or very important ().

Figure 2 Features of an inhaler considered “very important” by patients with COPD (Data from CitationMoore and Stone 2004).

Inhaler resistance is a factor that contributes to suboptimal inhalation of medication in patients with COPD. Over the years, there has been a trend to increase inhaler resistance. Patients have a preference for devices that allow them to inhale the medication quickly (Citationvan der Palen et al 2007). Eight popular DPIs seem to be acceptable with regard to their internal resistance, but the trend to increase the resistance of inhalers may have reached a critical point with regard to acceptability (Citationvan der Palen et al 2007).

Patients report overwhelmingly (98% vs 2%) that perceived benefits from using a SVN over a pMDI or DPI (eg, improved breathing, greater self-confidence, and less need to contact health care providers) outweigh perceived disadvantages (eg, longer time required for nebulizer treatment and cleaning the device) (CitationBarta et al 2002).

Pharmacoeconomics

Pharmacoeconomics has emerged to formalize the decision-making process for the adoption of new medications and devices. In addition, the implementation of clinical practice guidelines can be costly (CitationHaycox and Bagust 1999). In the US, in 2000, the total annual costs related to COPD were in excess of $US32 billion (CitationCOPD 2008). In the US, 97% of people over 65 years who receive incomplete Medicare coverage need supplemental insurance (CitationRoberts 2006). Since the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 only went into effect in 2006, its impact on suboptimal medication use is still to be determined (CitationMaio et al 2005).

Medication-related cost

Although underuse can result in morbidity and health care cost, the cost of the medication is believed to be one of the most important determinants of underuse (CitationHanlon et al 2001; CitationStuart 2004; CitationMaio et al 2005). Tiotropium has demonstrated the highest expected net benefit for ratios of the willingness to pay per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) (CitationRutten-van Mölken et al 2007). The incremental cost per additional QALY is lower with tiotropium than salmeterol or ipratropium bromide (CitationOba 2007). The practice of offering tiotropium bromide for patients with COPD-related hospitalizations instead of ipratropium bromide is favored (CitationOnukwugha et al 2008). There is a potential overall cost saving of 83% after the addition of tiotropium to the medical regimen of patients with COPD (CitationLee et al 2006). Fluticasone – salmeterol (FLU – SAL) and budesonide – formoterol (BUD – FOR) are the most cost effective strategies. However, there is a slight superiority of FLU – SAL. Incremental cost-effectiveness of FLU – SAL versus SAL was 679.5 (US$1,001) per avoided exacerbation and 3.3 (US$4.86) per symptom-free day (CitationDal et al 2007).

Device-related cost

Important breakthroughs in biotechnology and nanotechnology have resulted in the creation of a myriad of aerosol devices that have dramatically improved medication delivery to patients with respiratory diseases (CitationDames et al 2007; CitationDhand 2008). However, these advances have come at a steep price. It is well known that the costs of both the DPIs and SVNs are substantially higher than pMDI devices for all classes of medication (CitationBrocklebank and Ram 2001), that there is lack of many DPIs in generic forms, and that while 80% of SVNs and medications are reimbursable by Medicare, pMDIs and DPIs are not covered (CitationRau 2005). Although spacers significantly improve drug delivery, the high cost of these simple attachments may be sufficient to deter many patients from using them. Although routine substitution of pMDI therapy for SVN therapy can be accomplished with considerable reductions in the hospital setting (CitationBowton et al 1992), several authors have reported that no aerosol delivery device could be categorically rated as not cost-effective (CitationPeters et al 2002).

Patient beliefs, experiences, and behaviors

Significant differences in health beliefs, experiences, and behaviors are observed between COPD patients with different levels of adherence. While education plays an important role on modifying beliefs, patients are likely to modify the recommended therapy based on how they feel or their level of dyspnea.

COPD patients with suboptimal adherence have insufficient understanding about their illness and the options for managing their illness, show a low level of satisfaction with and faith in the treating physician, and rely more on natural remedies (CitationGeorge et al 2005). They also perceive the management of COPD as a mystery and show low confidence in drug therapy (CitationTurner et al 1995; CitationIncalzi et al 2001; CitationGeorge et al 2005).

The degree of difficulty to handle some medications and patient satisfaction with the information shared by the doctors is the more significant patient experiences that correlate with adherence to therapy for COPD (CitationGeorge et al 2005). The level of patient satisfaction heavily depends on the adequacy of communication between clinician and patient as perceived by the patient. Although complexity of medication regimens, concerns about side effects, cost of treatment, and the number of regular medications in the regimen have been considered critical to adherence, these experiences have not been consistently correlated with poor adherence by all the studies (CitationGeorge et al 2005).

Since patients with COPD are often coached to increase their prescribed doses when exacerbations are identified, the behavior of decreasing the doses when feeling well explains quite well the frequency of underuse in some patients with COPD. This change in frequency of therapy creates confusion about medications and results in sometimes not taking any actions when exacerbations arrive (CitationGeorge et al 2005).

A recent meta-analysis (CitationDiMatteo et al 2007) suggested that the objective severity of patients’ disease conditions, and their awareness of this severity, can predict their adherence. Patients who are most severely ill with serious diseases may be at greatest risk for nonadherence to treatment. Depression further complicates therapy adherence among COPD patients. Depressed medical patients are 3 times more likely to be noncompliant with medication regimens, exercise, diet, health related behavior, vaccination, and appointments (CitationDiMatteo et al 2007). Patients with chronic illness are also likely to adhere to therapy if they trust the provider who prescribes the regimen, if there is evidence that the regimen is effective and does not cause distressing or frightening side effects that outweigh any therapeutic benefits, if the regimen does not significantly interfere with important daily activities, and if it does not have a significant impact on the individual’s sense of identity (CitationStrauss and Glaser 1975).

shows beliefs, experiences, and health behaviors identified as strong predictors of low adherence to treatment in 276 patients with COPD. Each item is listed in order of statistical significance compared with subjects with high adherence (CitationGeorge et al 2005).

Table 3 Beliefs, experiences, and health behaviors identified predictors of low adherence to treatment in 276 patients with COPD. The highlighted variables explained almost 20% variance in nonadherence in this study (CitationGeorge et al 2005)

Patient satisfaction, patient preferences, and quality of life

Although patient’s view of therapy is important as discussed above, relatively little has been investigated on the patient view of therapy involving monotherapy versus combination therapy and the use of a particular aerosol device. Most investigators assess the suitability of this form of therapy on response to lung function tests, reported improvements in exercise ability, and other indices of clinical efficacy mentioned above. Evaluation of issues such as well-being and symptom control, self-confidence, dependency, time and technical issues, as well as side effects and adherence provides a global assessment of quality of life. In a survey of 82 patients with chronic lung conditions on domiciliary nebulizer therapy, 98% of the patients receiving SVNs therapy reported favoring SVNs over pMDIs due to improved breathing, greater self-confidence, and less need to contact health care providers (CitationBarta et al 2002).

The greatest change in quality of life have been reported when combination LABA – ICS is used in patients with COPD (mean reduction of 3.0 units over 3 years) compared with a placebo group (a mean score of 48.4 at baseline, with an increase of 0.2 unit in the placebo group) (CitationCalverley et al 2007). The combination BUD – FOR has a more significant reduction in the St George Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) than the FLU – SAL or placebo (CitationD’Urzo et al 2001; CitationAaron et al 2007; CitationNannini et al 2007b).

Patients with COPD who are treated with an albuterol/ipratropium combination via SVN have statistically significant improvements from baseline in the SGRQ at 6 weeks. The concomitant use of SVN plus pMDI maintains significant improvement in total questionnaire score and symptom sub-scores at week 12 (CitationTashkin et al 2007).

Self-reported adherence

Although several techniques are used to measure adherence, the most commonly used is based on self-reports, which tend to overestimate adherence (CitationFarmer 1999). MARS is commonly used for self-reported adherence. A score of 25 indicates perfect adherence (CitationGeorge et al 2005).

Fifty percent of patients with COPD do not take their medications as prescribed (CitationJames et al 1985). Patients on regimens of up to 4 times daily who take less than 70% of the dose prescribed, and those on regimens of 5 times daily or over who take less than 60% of the dose prescribed, are defined as poorly adherent (CitationMoriskey et al 1986; CitationBosley et al 1996). Underuse, especially during periods of respiratory distress, is more common than overuse (CitationChryssidis et al 1981; CitationJames et al 1985; CitationDolce et al 1991).

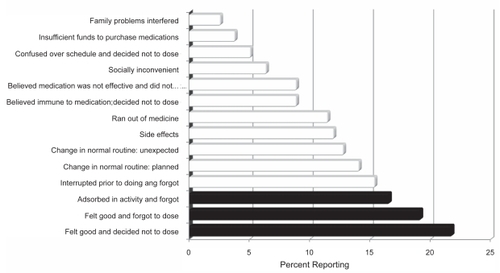

While a qualitative study of compliance to medication and lifestyle modification in patients with COPD found that all patients except one reported good adherence to medication (CitationJones et al 2004), the overall reported adherence to treatment in COPD ranges from 41.3% (CitationTaylor et al 1984) to 57% (CitationDolce et al 1991; CitationBosley et al 1994). Factors such as fear of dyspnea and feelings of vulnerability appear to contribute to improvement in compliance. Ninety-three patients were asked how often they missed doses from their nebulizers and 66% stated that they never did (61% of the nonadherers and 72% of the adherers). Six percent reported missing doses only once a month, 10% admitted to missing doses once a week, and 7% (11% of the nonadherers and 3% of the adherers) stated that they missed a dose once a day (CitationBosley et al 1994). Eleven percent of both adherers and nonadherers stated that they used the nebulizer only when they felt they needed to. Forgetting or deciding not to dose has been reported as the most common cause of poor adherence () (CitationDolce et al 1991). Forgetting is reported by 51% of the patients, and 31% of the patients report consciously deciding not to dose.

Figure 3 Common causes of poor adherence. (Data from CitationDolce et al 1991). Solid bars indicate the top three reasons cited for missing medications.

Demographics

An evaluation of predictors of patient adherence to long-term home nebulizer therapy in 985 patients with moderate to severe COPD enrolled in the Intermittent Positive Pressure Breathing (IPPB) Trial revealed that 49.4% of patients were nonadherent (CitationTurner et al 1995). Good adherence was predicted by white race, married status, abstinence from cigarettes and alcohol, serum theophylline level >9 pg/mL, more severe dyspnea, and reduced FEV1 (p < 0.05). Subjects who were adherent to nebulizer therapy were older, better educated, had a stable lifestyle, were more likely to report that the therapy made them feel better, and were more likely to keep clinic appointments.

Refill adherence tends to be lower in younger patients, but lower in men than women (ratio of repeat prescriptions; 40/60 men/women) (CitationRovelli et al 1989; CitationRand et al 1995; CitationLeventhal and Crouch 1997). Men seem to have higher oversupplies (25%) than women (21%) and women slightly more undersupplies (22%) than men (20%) (CitationAndersson et al 2005). Older patients typically have more difficulty with the correct use of the inhaler than younger patients but there seems to be no difference in errors between men and women (Citationvan Beerendonk et al 1998).

A study on adherence to prescribed regimens of 74 patients with COPD reported that almost 54% of the patients (men = 27, women = 15) stopped their medications periodically over the previous 3 months, 47% (men = 26, women = 11) noted forgetting doses over the previous 3 months, and 44% (men = 23, women = 11) acknowledged being “careless” in taking their medications (CitationDolce et al 1991). Thirty-nine patients (men = 25, women = 14) reported using more medication than was prescribed in times of distress. Thirty-eight percent of the men and 12% of the women used their inhaled medications with unsatisfactory technique.

Independent variables that are significantly associated with correct user of pMDI included sex and smoking status (CitationLuk et al 2006). Men were more likely to use pMDI correctly: 77% of men used pMDI correctly, but only 33% of women used pMDI correctly. Non-smokers were more likely to have correct inhaler technique, whereas smokers were less likely. No significant association was observed between age, drinking, education level or living condition and correct pMDI technique.

Impact of teaching

Although patients may read the instruction leaflet and receive face-to-face instruction, it is critical to evaluate whether or not patients are able to use the aerosol delivery device correctly. Patients’ interest in reading written medical information such as how to use the inhaler may be influenced by several patient factors including disease state, health locus of control, coping style, health literacy levels, and occupation (CitationKoo et al 2006). Since non-adherent patients have a tendency to report more confusion about medications than the highly adherent group, health care providers may need to spend more time especially with the elderly and those patients with polypharmacy (CitationGeorge et al 2005).

Even immediately after face-to-face instruction patients make mistakes. In a study comparing the Diskus and the Turbuhaler DPIs, 8% of patients made mistakes using the Diskus DPI and 26% using the Turbuhaler DPI right after reading the instruction leaflets (Citationvan der Palen et al 1998). Retention of instructions on appropriate use of the devices is progressively lost over time (Citationvan der Palen et al 1997). Inhalation technique was evaluated on average 6 months after they had received 3 different forms of instruction. Ninety-seven percent of the patients with small-group instruction demonstrated a good inhalation technique in comparison to 75% after video instruction, and 76% after personal instruction.

Using “ideal” technique as an outcome, the relative risk of all steps correct in teaching intervention groups compared with non-intervention groups has been around 2.08 (95% CI 1.59–2.78). The evidence shows that there is no difference between the pMDI and DPI. Any initial difference between the pMDI and DPI appears to be related partly to selection bias since appropriate inhaler technique achieved after a period of teaching has shown equivalent results for both pMDI and DPI (CitationBrocklebank and Ram 2001). The inhaler technique improves by counseling and the percentage of subjects performing steps correctly may double (CitationLuk et al 2006).

Evaluation of the proportion of patients with COPD who are compliant with ICS use after education in a 1-year follow up showed no significant difference when compared with those who did not get the education (CitationGallefos et al 1999). However, the educated patients with COPD received less than half the amount of SABAs as rescue medications compared with the control group.

A sizeable number of primary care physicians treating patients with COPD are not aware of the GOLD guidelines and seem unclear about the role of inhaled medications at different stages of COPD (Foster et al 2007). Since primary care physicians provide care for a large percentage of patients with mild-to-moderate COPD, their diagnostic skills along with the knowledge and implementation of the guidelines is critical to the education, clinical outcome, and adherence to therapy of their patients with COPD.

Summary

By considering only adherence to medications and the impact of teaching, we are falling short of recognizing the critical role played by other forms of nonpharmacologic treatment such as smoking cessation, alternative medicine, diet, exercise, and psychotherapy and their impact at different stages of COPD and/or in patients of different cultures. All aspects of therapy and the impact each one has on the currently reported poor adherence to COPD therapy need to be evaluated. Adherence to therapy at different stages of COPD is important since the extent of impairment influences perceived symptoms, medication algorithms, ability to adhere with therapy and perceived benefit of medication. This distinction could have significant implications in important outcomes discussed earlier. However, we could not find reports that measured the impact of specific stages of COPD on adherence to medication.

Therapies for COPD can be effective and improve outcomes only if well prescribed and if they are used by patients. The most common type of nonadherence to therapy is underuse. More than half of patients with COPD report missing or skipping doses of their medication (CitationGeorge et al 2005; CitationHaupt et al 2008; CitationKrigsman et al 2007a, Citationb, Citationc). Forgetting to dose is the most common situational factor that explains poor adherence (CitationDolce et al 1991; CitationBosley et al 1994). The decision not to dose due to feeling good is concerning. During respiratory distress, patients often report using more than the prescribed amount of medications (CitationBosley et al 1994; CitationDolce et al 1991).

Adherence also depends on clinical efficacy of the prescribed medications. In patients with COPD, a LABA – ICS combination produces a statistically significant and clinically relevant benefit without substantial differences between aerosol delivery systems. The superiority of combination inhalers should be viewed against the increased risk of side effects, particularly pneumonia (CitationCalverley et al 2007). The class of medication appears to be uniformly associated with adherence. There is a noticeable pattern for patients to report better adherence with corticosteroids and antibiotics than with theophylline, inhaled beta agonists, and inhaled anticholinergic agents. Unfortunately, the underlying causes of these differences have not been determined. The complexity of medication regimens frequently prescribed for patients with COPD adversely affect adherence to treatment (CitationKrigsman et al 2007a).

When selecting an aerosol delivery device for patients with COPD, the following aspects should be considered to improve adherence to therapy: device – medication availability; clinical setting; patient age and the ability to use the selected device correctly; device use with multiple medications; cost and reimbursement; medication administration time; convenience in both outpatient and inpatient settings; and physician and patient preference. Almost all popular inhalers seem to be acceptable when overall preference is assessed, but most patients choose their devices based on ease of use in general and during an exacerbation, the feel of the device in the hand, ease of opening the cap, and the ability to take the medication quickly in case of an impending exacerbation (Citationvan der Palen et al 2007). Patients using combined SVN therapy morning and night with midday inhaler use seem to have the most statistically significant improvements in quality of life. This concomitant regimen may provide the additional symptom relief offered by a SVN with the convenience of an inhaler when patients are away from home (CitationBalzano et al 2000; CitationTashkin et al 2007). Since most patients consider the pMDI to be more acceptable and the SVN to be more effective, these preferences should be taken into consideration when prescribing a maintenance aerosol inhalation treatment.

There is significant evidence showing that nearly 100% of patients with COPD make errors on the steps necessary to adequately use inhalers and many patients with COPD display a technique that possibly delivers an inadequate dose of medication (CitationHesselink et al 2001; CitationRau 2005; CitationLuk et al 2006). However, the number of instructions needed to obtain a perfect inhalation technique and the type of instruction that sustains patient’s mastery over time has not been clearly defined. Regular instructions, supervision, and check up of inhalation technique are the responsibility of the treating physician. Under real-life conditions, inappropriate use of inhalers is common and strongly correlates with a lack of instruction by the caregiver (Sestini et al 2007). The benefit of providing mere information and well-written instructions without “hands-on” demonstration has been thought as not providing information at all (Sestini et al 2007). Health professionals need to assess the utility of written medical information in the tailoring of patient education to meet patient needs.

Although insufficient funds have been reported of limited importance as a factor limiting adherence to a medication regimen (CitationDolce et al 1991), pharmacoeconomics is considered a relevant issue in clinical practice (CitationRoberts 2006). If reimbursement is considered, SVNs may be more cost effective and may explain why an increasing number of patients request a change to SVN (CitationRau 2005). Cost of the aerosol delivery device is at least as important as or perhaps more important than cost of the medication for adherence to therapy.

Patients’ acceptance and knowledge of the disease process as well as the recommended treatment, faith in the treatment, effective patient – clinician interaction are all critical for optimal medication adherence in patients with COPD. Psychological factors such as depression in patients with COPD have not been extensively studied. Depression may cause a patient to neglect themselves and their treatment and influence respiratory symptoms by being a cause of nonadherence. It is very possible that the increased sense of impairment in quality of life is associated with poor adherence to treatment (CitationDiMatteo et al 2000, Citation2007). Although some studies have revealed an association between demographic variables such as gender, age, and race to adherence, studies with larger samples are needed (CitationAndersson et al 2005; CitationLuk et al 2006).

There is a need for further research to determine how, when, and where in the course of COPD patients need to be educated on all aspects of their disease to improve adherence to their prescribed therapeutic regimen. Physicians’ role on adherence should be thoroughly investigated to establish strategies that improve adherence since current evidence has been focused mostly on the patient level. The impact of poor implementation of existing guidelines for COPD by physicians on patients’ adherence to treatment has been poorly investigated. Only about 45% of primary care physicians taking care of patients with COPD are aware of major COPD guidelines. However 75% of them do not use them to prescribe therapy for their patients with COPD (Foster et al 2007). The optimal use of recent advances in medicine depends heavily on developing effective communication between health care professionals and their patients (CitationMellins et al 1992). Strong education initiatives enable patients to respond effectively to the prescribed therapeutic regimens. A collaborative self-management approach recognizes the patient’s role in making his or her own health decisions and the physician’s role as an educator and facilitator of the patient’s health decisions (CitationBarry 2003). Health care practitioners should recognize the complexity of prescribed treatments and routinely utilize strategies to promote patient adherence.

Improving efforts by the physicians to increase education about the illness and the treatment options along with the inclusion of psychological treatments in management plans is critical to improving adherence to therapy in patients with COPD who find every day a challenge to adhere to their therapeutic regimen.

Disclosures

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- AaronSDVandemheenKLFergussonDCanadian Thoracic Society/Canadian Respiratory Clinical Research Consortium2007Tiotropium in Combination with Placebo, Salmeterol, or Fluticasone – Salmeterol for Treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseAnn Intern Med1465455517310045

- AnderssonKMelanderASvenssonC2005Repeat prescriptions: refill adherence in relation to patient and prescriber characteristics, reimbursement level and type of medicationEur J Public Health15621616126746

- AppletonSPoolePSmithB2006Long-acting beta2-agonists for poorly reversible chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev193CD00110416855959

- BalzanoGBattiloroRBiraghiM2000Effectiveness and acceptability of a domiciliary multidrug inhalation treatment in elderly patients with chronic airflow obstruction: metered dose inhaler versus jet nebulizerJ Aerosol Med13253310947321

- BarryMJ2003Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: developing comprehensive managementRespir Care4812253414651763

- BartaSCrawfordARobertsC2002Survey of patients’ views of domiciliary nebulizer treatment for chronic lung diseaseRespir Med963758112117035

- BosleyCMCordenZMReesPJ1996Psychological factors associated with use of home nebulized therapy for COPDEur Respir J92346508947083

- BosleyCMParryDTCochraneGM1994Patient compliance with inhaled medication. Does combining beta agonists with corticosteroids improve compliance?Eur Respir J750498013609

- BowtonDLGoldsmithWMHaponikEF1992Substitution of metered-dose inhalers for hand-held nebulizers. Success and cost savings in a large, acute-care hospitalChest10130581346514

- BrocklebankDRamF2001Comparison of the effectiveness of inhaler devices in asthma and chronic obstructive airways disease: a systematic review of the literatureHealth Technology Assessment5115511701099

- BrownPHLenneyLArmstrongS1992Breath-actuated inhalers in chronic asthma: comparison of Diskhaler and Turbuhaler for delivery of beta-agonistsEur Respir J51143451358674

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBTORCH investigators2007Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med3567758917314337

- CalverleyPMBonsawatWCsekeZ2003Maintenance therapy with budesonide and formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J22912914680078

- CalverleyPPauwelsDRLöfdahlCG2005Relationship between respiratory symptoms and medical treatment in exacerbations of COPDEur Respir J264061316135720

- CalverleyPPauwelsRVestboJ2003Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trialLancet3614495612583942

- Food and Drug Administration2007Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. drugs@FDARockville, MD URL: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/Accessed April 22, 2008

- ChapmanKRArvidssonPChuchalinAG2002The addition of salmeterol 50 microg bid to anticholinergic treatment in patients with COPD: a randomized, placebo controlled trialCan Respir J91788512068339

- ChrischillesEGildenDKubisiakJ2002Delivery of ipratropium and albuterol combination therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effectiveness of a two-in-one inhaler versus separate inhalersAm J Manag Care89021112395958

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)Fact sheet No 315. November 2007 [online]Accessed February 26, 2008 URL: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs315/en/index.html

- ChryssidisEFrewinDBFrithPA1981Compliance with aerosol therapy in COPDNZ Med J25037577

- CochraneGM1992Therapeutic compliance in asthma: its magnitude and implicationsEur Respir J5122241577134

- CromptonGK1990The adult patient’s difficulties with inhalersLung168Suppl658622117176

- D’UrzoADDe SalvoMCRamirez-RiveraA2001In patients with COPD, treatment with a combination of formoterol and ipratropium is more effective than a combination of salbutamol and ipratropium: a 3-week, randomized, double-blind, within-patient, multicenter studyChest11913475611348938

- DalNREandiMPradelliL2007Cost-effectiveness and healthcare budget impact in Italy of inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators for severe and very severe COPD patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis21697618044689

- DamesPGleichBFlemmerA2007Targeted delivery of magnetic aerosol droplets to the lungNature Nanotechnol24959918654347

- DhandR2008Aerosol delivery during mechanical ventilation: from basic techniques to new devicesJ Aerosol Med214560

- DiMatteoMRHaskardKBWilliamsSL2007Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysisMed Care45521817515779

- DiMatteoMRLepperHSCroghanTW2000Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherenceArch Intern Med1602101710904452

- DolceJJCrispCManzellaB1991Medication Adherence Patterns in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseChest99837412009784

- DolovichMBAhrensRCHessDR2005Device selection and outcomes of aerosol therapy: evidence-based guidelinesChest1273357115654001

- DompelingEVan GrunsvenPEVan SchayckCP1992Treatment with inhaled steroids in asthma and chronic bronchitis: longterm compliance and inhaler techniqueFam Pract9161661505703

- FarmerKC1999Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practiceClin Ther2110749010440628

- GallefossFBakkePS1999How does patient education and self-management among asthmatics and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affect medication?Am J Respir Crit Care Med1602000510588620

- GeorgeJKongDCThomanR2005Factors associated with medication nonadherence in patients with COPDChest128319820416304262

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD Updated 2007 [online]Accessed February 26, 2008 URL: http://www.goldcopd.com/Guidelineitem.asp?l1=2&l2=1&intId=989

- GrossNTashkinDMillerR1998Inhalation by nebulization of albuterol-ipratropium combination (Dey combination) is superior to either agent alone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration65354629782217

- HananiaNADarkenPHorstmanD2003The efficacy and safety of fluticasone propionate (250 microg)/salmeterol (50 microg) combined in the diskus inhaler for the treatment of COPDChest1248344312970006

- HanlonJTSchmaderKERubyCM2001Suboptimal prescribing in elderly inpatients and outpatientsJ Am Geriatr Soc49200911207875

- HarrowBSStromBLGansJA1997Impact of pharmaceutical under-utilization: a study of insurance drug claims dataJ Am Pharm Assoc (Wash)NS3751169479401

- HauptDKrigsmanKNilssonJL2008Medication persistence among patients with asthma/COPD drugsPharm World Sci 5 Feb [Epub ahead of print]

- HajjarEHanlonJTSloaneRJ2005Unnecessary drug use in frail older people at hospital dischargeJ Am Geriatr Soc5315182316137281

- HaycoxABagustA1999Clinical guidelines: the hidden costsBMJ31839139933210

- HaynesRBTaylorDWSackettDL1979Compliance in healthcareBaltimore, MDJohns Hopkins University Press17

- HesselinkAEPenninxBWWijnhovenHA2001Determinants of an incorrect inhalation technique in patients with asthma or COPDScand J Prim Health Care192556011822651

- IncalziRAPedoenCOnderG2001Predicting length of stay of older patients with exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAging13495711292153

- InselKCRemingerSLHsiaoCP2006The negative association of independent personality and medication adherenceJ Aging Health1840741816648393

- JamesPNEAndersonJBPriorJG1985Patterns of drug taking in patients with chronic airflow obstructionPostgrad Med J617102859583

- JonesRCMHylandMEHanneyK2004A qualitative study of compliance with medication and lifestyle modification in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)Primary Care Respir J131495416701658

- KaplanRMRiesAL2005Quality of life as an outcome measure in pulmonary diseasesJ Cardiopulm Rehabil253213116327524

- KaplanRMToshimaMTAtkinsCJO’KeeneJKShumakerSA1990Behavioral interventions for patients with COPDAdoption and Maintenance of Behavior for Optimal HealthNew YorkSpringer. Verlag

- KooMKrassIAslaniP2006Enhancing patient education about medicines: Factors influencing reading and seeking of written medicine informationHealth Expect91748716677196

- KrigsmanKLarsJGRingL2007cRefill adherence for patients with asthma and COPD: comparison of a pharmacy record database with manually collected repeat prescriptionsPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf16441817006959

- KrigsmanKMoenJNilssonJL2007aRefill adherence by the elderly for asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease drugs dispensed over a 10-year periodJ Clin Pharm Ther326031118021338

- KrigsmanKNilssonJLRingL2007bAdherence to multiple drug therapies: refill adherence to concomitant use of diabetes and asthma/COPD medicationPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf161120817566142

- LeeKHPhuaJLimTK2006Evaluating the pharmacoeconomic effect of adding tiotropium bromide to the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in SingaporeRespir Med1002190616635566

- LeventhalEACrouchMPetrieKJWeinmanJ1997Are there differentials in perceptions of illness across the life-span?Perceptions of health and illnessAmsterdamHarwood Academic Publishers77102

- LeyPBradshawPWEavesL1973A method for increasing patients’ recall of information presented by doctorsPsychol Med3217204715854

- LiptonHLBeroLABirdJA1992Undermedication among geriatric outpatients: Results of a randomized controlled trialAnn Rev Gerontol Get1295108

- LucasASmeenkFSmeeleI2008Overtreatment with inhaled corticosteroids and diagnostic problems in primary care patients, an exploratory studyFam Pract Epub ahead of print

- LukHChanPLamF2006Teaching chronic obstructive airway disease patients using a metered-dose inhalerChin Med J11916697217042981

- MahlerDAWirePHorstmanD2002Effectiveness of fluticasone propionate and salmeterol combination delivered via the Diskus device in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med16610849112379552

- MaioVPizziLRoummAr2005Pharmacy utilization and the Medicare Modernization ActMilbank Q831013015787955

- McFaddenER1986Inhaled aerosol bronchodilatorsBaltimoreWilliams and Wilkins

- MellinsRBEvansDZimmermanB1992Patient compliance. Are we wasting our time and don’t know it?Am Rev Respir Dis1461376771456550

- MooreACStoneS2004Meeting the needs of patients with COPD: patients’ preference for the Diskus inhaler compared with the HandihalerInt J Clin Pract584445015206499

- MoriskeyDGreenLLevineD1986Concurrent and predictive validity of a self reported measure of medication adherenceMed Care2467743945130

- NanniniLCatesCJLassersonTJ2007aCombined corticosteroid and long-acting beta-agonist in one inhaler versus placebo for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev4CD003794

- NanniniLCatesCJLassersonTJ2007bCombined corticosteroid and long-acting beta-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting beta-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev4CD00682917943918

- NanniniLCatesCJLassersonTJ2007cCombined corticosteroid and long-acting beta-agonist in one inhaler versus inhaled steroids for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev4CD00682617943917

- NilssonJLGJohanssonHWennbergM1995Large differences between prescribed and dispensed medicines could indicate undertreatmentDrug Inf J2912436

- ObaY2007Cost-effectiveness of long-acting bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMayo Clin Proc825758217493425

- OnukwughaEMullinsCDDelisleS2008Using cost-effectiveness analysis to sharpen formulary decision-making: the example of tiotropium at the Veterans Affairs Health Care SystemValue Health Epub ahead of print

- PetersJStevensonMBeverleyC2002The clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of inhaler devices used in the routine management of chronic asthma in older children: a systematic review and economic evaluationHealth Technol Assess65

- RamseySD2000Suboptimal medical therapy in COPDChest11733S7S10673472

- RandCSNidesMCowlesMKfor the Lung Health Study Research Group1995Long-term metered-dose inhaler adherence in a clinical trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med152580887633711

- RashidA1982Do patients cash prescriptions?BMJ2842466797628

- RauJL2005The inhalation of drugs: advantages and problemsRespir Care503678215737247

- RobertsM2006Racial and ethnic differences in health insurance coverage and unusual source of health care, 2002Rockville, MDAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS Chartbook 14. AHRQ Pub no 06-0004

- Rodriguez-RoisinR2005The airway pathophysiology of COPD: implications for treatmentInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis225362

- RovelliMPalmeriDVosslerE1989Noncompliance in organ transplant recipientsTransplant Proc2183342650282

- Rutten-van MölkenMPOostenbrinkJBMiravitllesM2007Modelling the 5-year cost effectiveness of tiotropium, salmeterol and ipratropium for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in SpainEur J Health Econ81233517370096

- Serra-BatllesJPlazaVBadiolaC2002Patient perception and acceptability of multidose dry powder inhalers: a randomized crossover comparison of Diskus/Accuhaler with TurbuhalerJ Aerosol Med15596412006146

- SichletidisLKottakisJMarcouS1999Bronchodilatory responses to formoterol, ipratropium, and their combination in patients with stable COPDInt J Clin Pract531858810665129

- SinDDMcAlisterFAManSF2003Contemporary management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: scientific reviewJAMA29023011214600189

- SireyJARauePJAlexopoulosGS2007An intervention to improve depression care in older adults with COPDInt J Geriatr Psychiatry22154917173354

- SmythHD2005Propellant-driven metered-dose inhalers for pulmonary drug deliveryExpert Opin Drug Deliv21537416296735

- SniderGL1985Distinguishing among asthma, chronic bronchitis, and emphysemaChest87Suppl 135S39S3964740

- SteinmanMALandefeldCSRosenthalGE2006Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older peopleJ Am Geriatr Soc5415162317038068

- StuartB2004Navigating the new Medicare drug benefitAm J Geriatr Pharmacother2758015555481

- StraussALGlaserBG1975Chronic illness and the quality of lifeSt. LouisMosby

- SzafranskiWCukierARamirezA2003Efficacy and safety of budesonide/formoterol in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J21748112570112

- TashkinDPKleinGLColmanSS2007Comparing COPD treatment: nebulizer, metered dose inhaler, and concomitant therapyAm J Med1204354117466655

- TaylorDRKinneyCDMcDevittDC1984Patient compliance with oral theophylline therapyBr J Clin Pharm171520

- ThompsonJIrvineTGrathwohlK1994Misuse of metered-dose inhalers in hospitalized patientsChest105715178131531

- TurnerJWrightEMendellaL1995Predictors of patient adherence to long-term home nebulizer therapy for COPD. The IPPB Study Group. Intermittent Positive Pressure BreathingChest1083944007634873

- Van BeerendonkIMestersIMuddeAN1998Assessment of the inhalation technique in outpatients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using a metered-dose inhaler or dry powder deviceJ Asthma35273799661680

- van der PalenJEijsvogelMKuipersBF2007Comparison of the Diskus® Inhaler and the Handihaler® Regarding Preference and Ease of UseJ Aer Med203844

- van der PalenJKleinJJKerkhoffAHM1994Poor technique in the use of inhalation drugs by patients with chronic bronchitis/pulmonary emphysemaNed Tijdschr Geneeskd1381417228047182

- van der PalenJKleinJJKerkhoffAHM1995Evaluation of the effectiveness of four different inhalers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax501183878553275

- van der PalenJKleinJJKerkhoffAH1997Evaluation of the long-term effectiveness of three instruction modes for inhaling medicinesPatient Educ Couns32S87S959516764

- van der PalenJKleinJJSchildkampAM1998Comparison of a new multidose powder inhaler (Diskus/Accuhaler) and the Turbuhaler regarding preference and ease of useJ Asthma35147529576140

- WindsorBAGreenLWRoseman3M1980Health promotion and maintenance for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a reviewJ Chronic Dis335126985916

- WoodmanKBremnerPBurgessC1993A comparative study of the efficacy of beclomethasone dipropionate delivered from a breath activated and conventional metered dose inhaler in asthmatic patientsCurr Med Res Opin136198325043

- World Health Organization2003Adherence to long-term therapiesEvidence for actionGenevaWorld Health Organization

- World Health OrganizationChronic Respiratory Diseases [online]Accessed February 26, 2008 URL: http://www.who.int/gard/publications/chronic_respiratory_diseases.pdf

- YangIAFongKMSimEH2007Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev2CD00299117443520