Abstract

In the current study, the prevalence of the most common psychological disorders in COPD patients and their spouses was assessed cross-sectionally. The influence of COPD patients’ and their spouses’ psychopathology on patient health-related quality of life was also examined. The following measurements were employed: Forced expiratory volume in 1 second expressed in percentage predicted (FEV1%), Shuttle-Walking-Test (SWT), International Diagnostic Checklists for ICD-10 (IDCL), questionnaires on generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life (St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), European Quality of Life Questionnaire (EuroQol), a modified version of a Disability-Index (CDI)), and a screening questionnaire for a broad range of psychological problems and symptoms of psychopathology (Symptom-Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R)). One hundred and forty-three stable COPD outpatients with a severity grade between 2 and 4 (according to the GOLD criteria) as well as 105 spouses took part in the study. The prevalence of anxiety and depression diagnoses was increased both in COPD patients and their spouses. In contrast, substance-related disorders were explicitly more frequent in COPD patients. Multiple linear regression analyses indicated that depression (SCL-90-R), walking distance (SWT), somatization (SCL-90-R), male gender, FEV1%, and heart disease were independent predictors of COPD patients’ health-related quality of life. After including anxiousness of the spouses in the regression, medical variables (FEV1% and heart disease) no longer explained disability, thus highlighting the relevance of spouses’ well-being. The results underline the importance of depression and anxiousness for health-related quality of life in COPD patients and their spouses. Of special interest is the fact that the relation between emotional distress and quality of life is interactive within a couple.

Introduction

Comorbid symptoms of anxiety and depression are common in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (CitationYohannes et al 2006) and cause a number of negative effects. Compared with non-depressed COPD patients, COPD patients with elevated depression scores show lower health-related quality of life (CitationMikkelsen et al 2004; CitationYohannes et al 2006; CitationNg et al 2007), a lower level of functioning (CitationKim et al 2000), longer and more frequent hospital stays (CitationNg et al 2007), and increased mortality, as shown in prospective studies (CitationCrockett et al 2002; CitationNg et al 2007). Similarly, increased levels of anxiety lead to impairment of quality of life (CitationKim et al 2000; CitationDi Marco et al 2006) and more frequent hospital admissions in COPD patients (CitationGudmundsson et al 2005; CitationYohannes et al 2005). However, the reported prevalence rates for comorbid symptoms of depression or anxiety are highly variable: in studies using anxiety and depression self-report questionnaires, these rates range from 13% and 7% (CitationEngström et al 2001) to 96% and 79%, respectively (CitationBorak et al 1991; CitationHynninen et al 2005). The few studies that assessed categorical diagnoses by means of international diagnosis systems such as the ICD-10 (CitationWHO 1993) or the DSM-III-R/-IV (CitationSaß et al 1996) also reported inconsistent but lower prevalence rates, ranging from 10% to 35% and 16% to 47%, respectively (CitationYellowlees et al 1987; CitationKarajgi et al 1990; CitationAghanwa and Erhabor 2001; CitationAydin and Ulusahin 2001; CitationStage et al 2003). However, the generalization of these results is limited by the small sample sizes and the absence of control groups.

The inconsistency of previous findings may partly be due to varying inclusion criteria (eg, COPD grade 1–4, out-patients versus in-patients, stable or with exacerbation, with or without oxygen therapy) research strategies, and employed instruments. The use of screening questions that are highly sensitive to detect symptoms of anxiousness and dysphoria generally result in an extremely high proportion of individuals screened positive (CitationKunik et al 2005). In contrast, self-report questionnaires assessing levels of symptomatology result in a smaller proportion of potentially disordered individuals. The presence of a clinically significant mental disorder, however, can be determined only on the basis of categorical diagnostics according to international classification systems such as the ICD-10 (CitationWHO 1993). These diagnoses are based on a defined set of symptom criteria. Precise case definition criteria for each symptom (severity, frequency, duration) as well as explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria usually result in high inter-rater reliabilities. Thus, categorical diagnostics can be considered the gold standard in diagnosing mental disorders. Overall, though, few studies have employed such elaborate classification systems of mental disorders, and even fewer have compared their results with those of control groups (eg, CitationAghanwa and Erhabor 2001; CitationLin et al 2005).

It is well documented that spouses of patients with other severe and life-threatening somatic diseases may encounter comparable psychosocial and emotional distress as the patients themselves. However, very few COPD studies have addressed this issue (CitationKim et al 2000; CitationKanervisto et al 2007; CitationPinto et al 2007). In two studies, the spouses of COPD patients reported levels of loneliness and depressive mood comparable to the levels reported by the patients themselves (CitationKeele-Card et al 1993; CitationKara et al 2004). To our knowledge, there have been no studies on the prevalence of mental disorders in spouses of COPD patients, even though their state of health may be of particular importance for the supportive care of patients.

The first purpose of the present study was to compare the prevalence of mental disorders in COPD patients with the prevalence in two reference groups of elderly persons. The second purpose was to investigate the prevalence of mental disorders in the spouses. Specifically, we examined the following questions: (1) Does the psychopathology of the patients and that of their spouses correlate with the health-related quality of life of the patients? (2) How is the COPD-related disability of spouses related to clinical variables of patients?

Methods

Measures

First, a bodyplethysmography (MasterScreenBody by Viasys/Jaeger) was performed, in accordance with the American Thoracic Society guidelines, as well as a shuttle walking test (CitationSingh et al 1992; CitationDyer et al 2002). The subjects performed only one test at baseline. Three to 10 days later, psychological diagnostics were carried out in the homes of the COPD patients by a clinical psychologist (Kerstin Kühl), who was blind to the results of lung function testing. At the beginning of the home assessment, patients and their spouses underwent a screening interview to assess for the presence of cardinal symptoms of depressive disorders (ICD-10 diagnosis of depressive episode [F32] or recurrent depressive disorder [F33]), dysthymia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, as well as nicotine and alcohol abuse. For participants screened positive, categorical diagnostics (International Diagnostic Checklists for ICD-10) (CitationHiller et al 1997) were used. Subsequently, the following questionnaires were applied:

The St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (German version: CitationHütter 2003)

The SGRQ assesses the subjective quality of life of COPD patients. Thus it cannot be rated by the spouses.

COPD Disability Index (CDI)

In contrast, COPD-related disability assessing reductions of social functioning and self-care can be rated both by patients and their spouses. The CDI is an adaptation of the Pain Disability Index (PDI) (CitationDillmann et al 1994). The original version comprises 7 items: family/home, responsibilities, recreation, social activity, occupation, sexual behavior, self-care, and life-support activities (breathing, sleeping, eating). For the purpose of the present study, item 7 (breathing, sleeping, eating) was limited to breathing. Since COPD is a respiratory disease, breathing, eating, and sleeping are affected differently and thus cannot be averaged in this study population. The degree of disability caused by the disease is rated on an 11-point rating scale for all respective aspects of life. In general, factor analyses with different patient groups and with spouses of pain patients have yielded one factor and confirmed the unidimensionality of the construct (CitationDillmann et al 1994), although there have been two exceptions (CitationTait et al 1987; CitationTait and Chibnall 2005). Spouses were instructed to evaluate their perceived disability due to their partner’s illness.

The European Quality of Life Questionnaire (EuroQol) (CitationSchulenburg et al 1998)

The EuroQol assesses the generic health-related quality of life by means of a visual analogue scale. The scale ranges from 0 (“the worst state of health to be imagined”) to 100 (“the best state of health to be imagined”).

The Symptom-Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) (CitationFranke 2000)

The SCL-90-R assesses physical and psychological symptoms within the last week. Only subscales that are relevant for the issue under investigation (depression, anxiousness, phobic anxiety, somatization) were included in the analysis. Two items of the somatization scale (chest pain and breathing difficulties) were excluded, since these symptoms might reflect actual symptoms of COPD rather than symptoms of psychopathology.

Statistical analysis

The data was analysed using SPSS (v. 15.0. SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Internal consistency for the modified COPD-Disability-Index (CDI) was determined using Cronbach’s alpha. Of particular note was the high internal consistency in the CDI (P-CDI = 0.92; S-CDI (without item 7 breathing) =0.86) (For reasons of clarity, variables assessed on COPD patients and their spouses will be labeled with P [for COPD patients’ data] and S [for spouses’ data].)The significant Pearson correlations between COPD-related disability (P-CDI) and the SGRQ in patients (SGRQ-S r = 0.59; SGRQ-A r = 0.74; SGRQ-I r = 0.81; SGRQ-T r = 0.83; all p < 0.01) support the convergent validity of this new instrument. In addition, the significant associations between COPD-related disability in the spouses (S-CDI) and the SGRQ in the patients (SGRQ-S r = 0.35; SGRQ-A r = 0.45; SGRQ-I r = 0.59; SGRQ-T r = 0.56; all p < 0.01) not only highlight the relationship between patient’s health and partner’s disability, but confirm that the CDI is a very short but nonetheless reliable and valid instrument.

The results of our patient and spouse samples will be compared with normative data of two representative samples of elderly persons (CitationWernicke et al 2000; CitationTrollor et al 2007). Comparisons for patients with and without mental disorders were computed by means of t-tests for independent samples and chi square tests. For nonparametrical variables Mann-Whitney U-test were analysed. Recent research (eg, CitationChavannes et al 2005; CitationCully et al 2006; CitationDi Marco et al 2006; CitationNg et al 2007) has highlighted nine variables (FEV1, walking distance, gender, heart disease, somatization, anxiousness, depression (SCL-90-R), phobic anxiety (SCL-90-R), depression/anxiety diagnoses) as relevant predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with COPD. These variables were included in a stepwise multiple linear regression to predict patients’ health-related quality of life (SGRQ). Furthermore, the part of explained variance of the COPD-related disability of the spouses (S-CDI) was calculated.

Patient sample

Over a period of 9 months, all COPD patients of a private pulmonary practice were consecutively asked if they wanted to take part in the study. Patients with a severity grade of 2, 3, or 4 (according to the GOLD criteria) who had been at the routine appointment 3 respectively 6 months before were included. All participants received €10 and a small present (candy) as reimbursement for their participation. Exclusion criteria were, for patients, illness exacerbation within the previous month or, for patients and spouses, a severe acute illness (such as myocardial infarction, tumor) within the last year. Of the 165 COPD patients who were approached, only 15 (9.1%) declined to participate. Ten participants – 7 patients (4.2%) and 3 spouses (2.7%) – had to be excluded for reasons of illness exacerbation (2), diagnosis of tumor (3), psychosis (1), missing data (1), possible dementia (2), or insufficient language abilities (1). Another couple was excluded from the comparison of couples because both were COPD patients. Thus, 143 COPD patients (and 105 spouses) were included in the analysis. The duration of illness was less than one year in 4.6% of patients, 1–3 years in 12.8% of patients, 3–10 years in 12.8 % of patients, and more than 10 years in 50.5% of patients. Within 12 months prior to the study, 15 patients (10.5%) had been admitted to hospital due to COPD exacerbation and two (1.4%) to a comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation.

Results

Comorbid mental disorders

Most of the 143 COPD patients (80.4%/75.2% of the spouses) did not fulfil the criteria of any of the investigated depressive or anxiety disorders ().

Table 1 Sample characteristics

Table 2 Comorbid mental disorders in COPD patients and their spouses

COPD patients and their spouses were compared with a representative German aging study, which also used categorical diagnoses (CitationWernicke et al 2000). The prevalence rates for anxiety and depressive disorders (except for dysthymia) were higher than in the reference sample for both patients and their spouses (see ). Only five out of these 29 patients were taking psychotropic medication and no patients were receiving any form of psychological support or psychotherapeutic treatment. The prevalence of anxiety or depressive disorders was not influenced by COPD severity (grade 2 = 23.6%; grade 3 = 26.5%; grade 4 = 18.2%; χ2 = 0.23, df = 2, p = n.s.). In the present study, 7.7% of COPD patients met criteria for alcohol abuse and/or dependence. Although this rate was lower than reported by CitationStage et al (2003), it was significantly higher compared with two reference samples (CitationWernicke et al 2000; CitationTrollor et al 2007).

As expected, only 4.9% of the patients had always been non-smokers, compared with 61.9% of the spouses. This difference is significant and cannot be explained by gender differences (females, Pearson’s χ2 = 51.26, df = 2, p < 0.001; males, Pearson’s χ2 = 14.40, df = 2, p < 0.001). The percentage of participants with clinically relevant SCL-90-R T-scores (ie, those with scores ≥ mean + 1 SD) was significantly higher in patients compared to spouses: somatization, 39.2% (vs 21.9%, Pearson’s χ2 = 8.31, df = 1, p < 0.004), depression (SCL-90-R), 29.4% (vs 16.2%, Pearson’s χ2 = 5.80, df = 1, p < 0.016), anxiousness, 25.2% (vs 15.2%, Pearson’s χ2 = 3.61, df = 1, p < 0.057), and phobic anxiety (SCL-90-R), 18.2% (vs 5.7%, Pearson’s χ2 = 8.37, df = 1, p < 0.004). There was a low but significant positive correlation between self-reported duration of illness and all SCL-90-R subscales – even after controlling for age and FEV1% (partial correlation: somatization rp = 0.24, depression rp = 0.24, anxiousness rp = 0.20, phobic anxiety rp = 0.22; all p < 0.05).

Quality of Life

It is important to note that the quality of life was considerably lower compared to the general 1 (EuroQol: CI = 76.3–77.1–77.9) in both patients (EuroQol: CI = 46.6–50.2–53.9) and spouses (EuroQol: CI = 62.6–66.5–70.5). COPD patients with mental disorders reported significantly higher scores on subscales for psychosocial impact (SGRQ-I) and health related quality of life (SGRQ-T) than patients without mental disorders (see ). There was no difference between COPD patients with and without mental disorders with regard to socio-demographic variables (age, gender), restriction of lung functioning (FEV1%), walking distance, or general health-related quality of life (EuroQol).

Table 3 Comparison of means in COPD patients with and without mental disorders

The nine variables (FEV1, walking distance, gender, heart disease, somatization, anxiousness, depression (SCL-90-R), phobic anxiety (SCL-90-R), depression/anxiety diagnoses), which had previously been identified as relevant predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with COPD, were included in a multiple regression model to predict health-related quality of life (SGRQ-T; ).

Table 4 Stepwise multiple linear regressions

The present study identified 6 variables (, model A, adjusted R2 = 0.64, p < 0.001) as significant predictors of health-related quality of life. In a second regression analysis, spouse variables were included in addition to the above listed patient variables (model B, adjusted R2 = 0.62, p < 0.001). The greatest proportion of variance in both models was explained by the patients’ depression scores (SCL-90-R), walking distance (SWT), somatization, and male gender. In model B, spouses’ anxiousness was a significant predictor of patients’ health related quality of life, while the objective measures FEV1% and heart disease were not found to be significant predictors.

In addition, we analyzed whether the predictor variables from the first regression analysis (model A) would also predict spouses’ perceived disability due to their partners’ illness (criterion: S-CDI) (). Twenty-seven percent of the variance (model C, adjusted R2 = 0.27, p < 0.001) of the S-CDI was explained by the patient variables somatization, walking distance (SWT), and depression (SCL-90-R), again confirming the close relationship of the partner’s well-being with patients’ health.

In the fourth regression analysis psychosocial impact of the COPD patients in the SGRQ and the extent of other physical symptoms (P-somatization) predicted COPD-related disability in the spouses (model D, adjusted R2: 0.36, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The present study investigated the prevalence of mental disorders and quality of life in 143 consecutive COPD patients attending a private pulmonary practice as well as 105 spouses.

Results revealed significantly increased prevalence rates for depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and alcohol related disorders in COPD patients compared to a representative German reference sample (CitationWernicke et al 2000) and a German aging study (CitationDHS 2005). Similarly, increased prevalence rates for depressive and anxiety disorders were found in patients’ spouses.

The high rates of alcohol abuse and dependence in patients in this study might be a result of more genuine response tendencies: during the screening of substance-related disorders – and only at this point – some of the spouses intervened and urged their partners to be more honest about the amount of alcohol consumption (CitationStage et al 2003).

The second aim of this study was to investigate predictors of quality of life in COPD patients and their spouses. Results identified 6 out of 9 theoretically derived variables (somatization, depression [SCL-90-R], walking distance [SWT], gender, FEV1%, heart disease) as significant predictors of health-related quality of life in COPD patients. When including spouse variables, the objective variables (FEV1%, heart disease) failed to remain significant predictors for patients’ quality of life, while symptoms of anxiousness in spouses explained substantial variance. This emphasizes the importance of spouses’ anxiousness for the health-related quality of life in the patients.

On the other hand, 36% of the total variance in spouses’ COPD-related disability could be explained by disease-specific psychosocial impact (SGRQ-I) and the physical condition of the patients (somatization). This is a further indication that spouses of COPD patients are substantially affected by the disease of their partners, a fact that previous studies have already highlighted (CitationKeele-Card et al 1993; CitationKara et al 2004; CitationKanervisto et al 2007; CitationPinto et al 2007).

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, despite a comprehensive psycho-diagnostic assessment, the number of investigated diagnoses was limited in the present study. Second, some diagnostic criteria were difficult to evaluate in this patient group. For example, in order to receive a diagnosis of panic disorder, symptoms must not be due to a medical condition. In the case of patients with comorbid heart disease or severe dyspnea this is difficult to decide. Third, the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow conclusions to be drawn about the causal relationship between COPD, psychological disorders, and quality of life in the patients or psychological diagnoses and quality of life in the spouses. Furthermore, no conclusions can be drawn about the causal relation between patient variables and psychological disorders or quality of life in their spouses. Fourth, patients included in this study were stable out-patients at a private pulmonary practice. The present results may thus not be generalized to hospitalized patients or patients with acute exacerbation.

Implications

Diagnostic

The extensive diagnostic assessment according to ICD-10 was only conducted with respect to diagnoses which have frequently been investigated in COPD patients. It is likely that alcohol dependency is a comorbid disorder which so far has not received enough attention.

It is important to point out that a considerate number of patients who did not fulfil criteria for a current diagnosis reported having experienced severe symptoms of depression or anxiety on a few days in the past year (often during periods of COPD exacerbation). However, if a patient fulfils all symptoms necessary for a diagnosis of depression for only 9 days, a diagnosis of depression (ICD-10 F32) cannot be given. Similarly, in panic disorder (ICD-10 F41.0) symptoms must not be due a medical factor in order to meet diagnostic criteria. For a diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), worries have to be disproportionate or unreasonable. In the present study, health-related worries did not count toward a diagnosis of GAD. This might account for the low prevalence rate of GAD in this study (5.6%) compared with 10%–15.8% (CitationYellowlees et al 1987; CitationKarajgi et al 1990; CitationAghanwa and Erhabor 2001) found in former studies. The prevalence of GAD found in this sample might thus underestimate the scale of clinically relevant anxiety and worries.

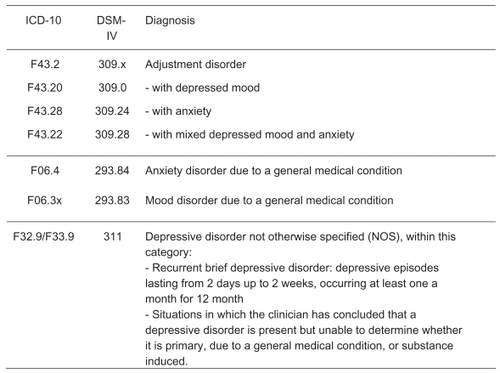

Even if some of the reported symptoms did not meet diagnostic criteria for the above mentioned reasons, they still reflect clinically relevant psychopathology (CitationRief et al 2005). Such clinically relevant syndromes can be diagnosed according to ICD-10, for example as adjustment disorder, and anxiety or mood disorder due to a general medical condition ().

The DSM-IV explicitly mentions COPD for anxiety disorder due to a medical condition (CitationFrances et al 1995) and assumes that anxiety may be a direct result of the chronic hyperventilation pattern or of neurobiologically increased CO2 sensitivity (CitationDratcu 2000; CitationMikkelsen et al 2004). Therefore, these diagnoses should be considered more rigorously in future COPD studies.

Intervention

Psychological disorders in patients should be treated pharmacologically and/or psychologically regardless of whether they are a direct consequence of the disease in the sense of an organic-related psychological disorder, an independent comorbid psychological disorder, or a reactive disorder. However, 70% of affected COPD patients refuse proposed pharmacological treatments (CitationYohannes et al 2001). This might be due to the large number of drugs already taken by such patients (on average 6.4, maximum of 17 in the present study).

Psychological interventions are often considered skeptically by patients and pneumologists. Hence it is important to point out the negative effects of increased anxiety or depression on the quality of life of COPD patients.

The high efficacy of cognitive–behavioral approaches in the treatment of anxiety disorders (CitationMitte 2005) and depression disorders (CitationMaat et al 2007) is beyond doubt. The efficacy of additional psychological interventions in patients with other somatic diseases, such as chronic pain (CitationHoffman et al 2007) or cancer (CitationNewell et al 2002) has also been demonstrated.

The efficacy of psychological interventions in COPD patients with comorbid anxiety or depressive disorders is yet unclear (CitationCoventry and Gellatly in press). There have only been a few studies with mostly small sample sizes. Two pilot studies (CitationLisansky and Clough 1996; CitationEiser et al 1997) reported improved quality of life (CitationLisansky and Clough 1996) but no reduced levels of anxiety. In a controlled, randomized cognitive–behavioral study, a one-session short-term intervention could significantly reduce anxiousness and depression in COPD patients (CitationKunik et al 2001). A small randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Citationde Godoy and de Godoy 2003) showed significantly decreased depression and anxiety levels after psychotherapy (including cognitive-behavioral interventions). Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy (CBT) in COPD patients with clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety resulted in a significant improvement of their quality of life (CitationKunik et al 2008). CBT did not differ from COPD education, however, which also resulted in significant improvements regarding quality of life, anxiety und depression. In both treatment groups, improvements were maintained until follow-up. However, it is questionable whether there was sufficient time for individualized CBT interventions when using groups of 10 participants (8 × 60 minutes).

Thus, in addition to the conventional COPD education and comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitations, which are effective in the short term (CitationCoventry and Hind 2007), it is essential to establish appropriate short-term psychological interventions for COPD patients with psychological comorbidity by therapists trained in behavior medicine. Future research should therefore focus on the development and evaluation of effective psychological interventions for COPD patients with psychological comorbidities.

Spouses

The finding that the spouses’ anxiousness is a predictor for the health-related quality of life in patients underscores the importance of involving anxious spouses in intervention programs. Future studies will have to show whether this is a helpful tool to indirectly improve health-related quality of life in patients.

Further investigations and panel studies are needed to analyze the influence of other psychological factors (eg, satisfaction in the relationship, social support/distress, coping or avoidance of physical effort) on the quality of life of COPD patients.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- AghanwaHSErhaborGE2001Specific psychiatric morbidity among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a Nigerian general hospitalJ Psychosom Res501798311369022

- AydinIOUlusahinA2001Depression, anxiety comorbidity, and disability in tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: applicability of GHQ-12Gen Hosp Psychiatry23778311313075

- BorakJSliwinskiPPiaseckiZ1991Psychological status of COPD patients on long term oxygen therapyEur Respir J459622026240

- ChavannesNHHuibersMJHSchermerTRJ2005Associations of depressive symptoms with gender, body mass index and dyspnea in primary care COPD patientsFam Pract22604716024555

- CoventryPAGellatlyJLImproving outcomes for COPD patients with mild-to-moderate anxiety and depression: A systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapyBr J Health PsycholIn press

- CoventryPAHindD2007Comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation for anxiety and depression in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Systematic review and meta-analysisJ Psychosom Res635516517980230

- CrockettAJCranstonJMMossJR2002The impact of anxiety, depression and living alone in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseQual Life Res113091612086116

- CullyJAGrahamDPStanleyMA2006Quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbid anxiety or depressionPsychosomatics47312916844889

- De GodoyDde GodoyRF2003A randomized controlled trial of the effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Phys Med Rehabil841154712917854

- DHS2005Substanzbezogene Störungen im AlterAhausLensing Druck

- Di MarcoFVergaMReggenteM2006Anxiety and depression in COPD patients: The roles of gender and disease severityRespir Med10017677416531031

- DillmannUNilgesPSailleP1994Behinderungseinschätzung bei chronischen Schmerzpatienten (PDI)Schmerz81001418415443

- DratcuL2000Panic, Hyperventilation and perceptuation of anxietyProg Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry24106989

- DyerCAESinghSJStockleyRA2002The incremental shuttle walking test in elderly people with chronic airflow limitationThorax5734811809987

- EiserNWestCEvansS1997Effects of psychotherapy in moderately severe COPD. A pilot studyEur Respir J10158149230251

- EngströmCPPerssonLOLarssonS2001Health-related quality of life in COPD: why both disease-specific and generic measures should be usedEur Respir J18697611510808

- FelkerBKatonWHedrickS2001The association between depressive symptoms and health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseGen Hosp Psychiatry23566111313071

- FrancesAFirstMBPincusHA1995DSM-IV GuidebookWashingtonAmerican Psychiatric Press

- FrankeGH2000Symptom-Checkliste von L.R. Derogatis (SCL-90-R)GöttingenBeltz

- GudmundssonGJansonCLindbergE2005Risk factors for rehospitalisation in COPD: role of health status, anxiety and depressionEur Respir J26414916135721

- HillerWZaudigMMombourW1997ICD-10 Internationale Diagnose ChecklistenGöttingenHogrefe and Huber

- HinzAKlaibergABrählerE2006Der Lebensqualitätsfragebogen EQ-5D: Modelle und Normwerte für die AllgemeinbevölkerungPsychother Psych Med56428

- HoffmanBMPapasRKChatkoffDK2007Meta-analysis of psychological interventions for chronic low back painHealth Psychol261917209691

- HütterBOSchumacherJKlaibergABrählerE2003SGRQ – St. Georges Respiratory QuestionnaireDiagnostische Verfahren zu Lebensqualität und WohlbefindenGöttingenHogrefe2805

- HynninenKMJBreitveMHWiborgAB2005Psychological characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a reviewJ Psychosom Res594294316310027

- KanervistoMKaistilaTPaavilainenE2007Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a family’s everyday life in Finland: Perceptions of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their spousesNurs Health Sci940717300544

- KaraMMiriciA2004Loneliness, depression, and social support of Turkish patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their spousesJ Nurs Scholarsh36331615636413

- KarajgiBRifkinADoddiS1990The prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Psychiatry14720012301659

- Keele-CardGFoxallMJBarronCR1993Loneliness, depression, and social support of patients with COPD and their spousesPublic Health Nurs10245518309892

- KimFHSKunikMEMolinariV2000Functional impairment in COPD patients. The impact of anxiety and depressionPsychosomatics414657111110109

- KunikMEVeazeyCCullyJA2008COPD education and cognitive behavioral therapy group treatment for clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD patients: a randomised controlled trialPsychol Med383859617922939

- KunikMERoundyKVeazeyC2005Surprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disordersChest12712051115821196

- KunikMEBraunUStanleyMA2001One session’s cognitive behavioral therapy for elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePsychol Med317172311352373

- LinMChenYMcDowellI2005Increased risk of depression in COPD patients with higher education and incomeChron Respir Dis213916279744

- LisanskyDPCloughDH1996A cognitiv-behavioral self-help educational program for patients with COPD : a pilot studyPsychother Psychosom65971018711089

- Maat deSMDekkerJSchoeversRA2007Relative efficacy of psychotherapy and combined therapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysisEur Psychiatry221817194571

- MikkelsenLRMiddelboeTPisingerC2004Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A reviewNord J Psychiatry58657014985157

- MitteK2005Meta-analysis of the efficacy of psycho- and phamacotherapy in panic disorder with and without agoraphobiaJ Affect Disord88274516005982

- NewellSASanson-FisherRWSavolainenNJ2002Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: overview and recommendations for future researchJ Natl Cancer Inst945588411959890

- NgT-PNitiMTanW-C2007Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med16760717210879

- PintoRAHolandaMAMedeirosMMC2007Assessment of the burden of caregiving for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med1012402817624751

- RiefWMartinAKlaibergA2005Specific effects of depression, panic, and somatic symptoms on illness behaviorPsychosom Med6759660116046373

- SaßHWittchenH-UZaudigM1996Diagnostisches und statistisches Manual psychischer Störungen DSM-IVGöttingenHogrefe

- Schulenburg Graf von derJMClaesCGreinerW1998Die deutsche Version des EuroQOL-FragebogensZ f Gesundheitswiss6320

- SinghSJMorganMDLSciottS1992Development of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstructionThorax471019241494764

- StageKBMiddelboeTPisingerC2003Measurement of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Nord J Psychiatry5729730112888404

- TaitRCChibnallJT2005Factor structure of the Pain Disability Index in workers’ compensation claimants with low back injuriesArch Phys Med Rehabil861141615954052

- TaitRCPollardCAMargolisRB1987The Pain Disability Index: Psychometric and validity dataArch Phys Med Rehabil68438413606368

- TrollorJNAndersonTMSachdevPS2007Prevalence of mental disorders in the elderly: The Australian National Mental Health and Well-Being-SurveyAm J Geriatr Psychiatry154556617545446

- WernickeTFLindenMGilbergR2000Ranges of psychiatric morbidity in the old and the very old results from the Berlin Aging Study (BASE)Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci250111910941985

- WHO1993Internationale Klassifikation psychischer Störungen - ICD-10 Kapitel V (F)BernHuber

- YellowleesPMAlpersJHBowdenJJ1987Psychiatric morbidity in patients with chronic airflow obstructionMed J Aust14630573821636

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyK2005Predictors of 1-year mortality in patients discharged from hospital following acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAge Aging344916

- YohannesAMBaldwinRCConnollyMJ2006Depression and anxiety in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAge Aging354579

- YohannesAMConnollyMJBaldwinRC2001A feasibility study of antidepressant drug therapy in depressed elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Geriatr Psychiatry16451411376459