Abstract

Introduction

Neurotrophic keratitis, a degenerative corneal disease caused by trigeminal nerve impairment, has many etiologies and remains very difficult to treat.

Methods

Case report of a 23-year-old male with a right corneal ulcer that failed to improve despite broad-spectrum antimicrobials.

Results

Prior diagnosis of disseminated lymphangiomatosis with a lesion in the right petrous apex effacing Meckel’s (trigeminal) cave in conjunction with a history of nonhealing corneal abrasions suggested a neurotrophic etiology. Drawstring temporary tarsorrhaphy, in addition to antibiotics and autologous serum, lead to successful clearing of the infection and resolution of the corneal ulcer. Visual acuity improved from light perception (LP) at the peak of infection to 20/40 six weeks after treatment.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, we report the first case of neurotrophic keratitis in a patient with disseminated lymphangiomatosis that caused a mass effect in Meckel’s (trigeminal) cave leading to compression of the trigeminal nerve. The antibiotic-resistant corneal ulcer was successfully treated with drawstring tarsorrhaphy, confirming the utility of this therapeutic measure in treating neurotrophic keratitis.

Introduction

Neurotrophic keratitis is a degenerative disease of the corneal epithelium due to interruption of the sensory innervation provided by the trigeminal nerve leading to full or partial corneal anesthesia.Citation1 Decreased corneal sensation results in increased susceptibility to epithelial injury and mitigated healing responses in part due to reduced tearing, trophic factors, and blinking reflexes. In addition, increased mucous secretions lead to tears with increased viscosity further impairing corneal lubrication.Citation2 Neurotrophic keratitis can quickly progress to corneal ulceration, melting, and perforation if not treated quickly and appropriately.

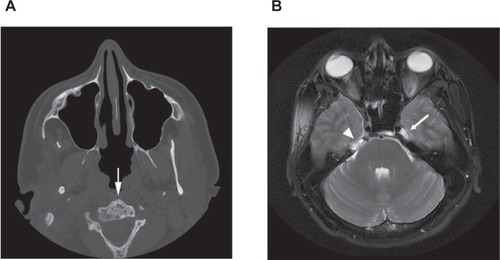

Corneal hypoesthesia has many potential etiologies, including infection with herpes simplex or varicella zoster virus infections, fifth cranial nerve palsy due to surgery or other trauma, neoplasia (especially acoustic neuroma), aneurysm, or congenital conditions, including familial dysautonomia (Riley–Day syndrome), Goldenhar–Gorlin syndrome, Mobius syndrome, and familial corneal hypesthesia. To our knowledge, we report here the first case of neurotrophic keratitis in a patient with congenital disseminated lymphangiomatosis, a disorder that, in this patient, affected the boney structures surrounding Meckel’s (trigeminal) cave (see ) leading to compression of the trigeminal nerve and subsequent corneal anesthesia.

Figure 1 A) Head CT without contrast demonstrating generalized bony changes associated with disseminated lymphangiomatosis. Note the bubbly appearance of the C2 vertebral body (arrow). B) T2-weighted axial MRI image of the head showing a normal cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) signal in the left Meckel’s (trigeminal) cave (arrow). A lesion in the right petrous apex (the bone is not well seen on MRI) has effaced Meckel’s (trigeminal) cave on the right (arrowhead).

Case report

A 23-year-old male presented to his local ophthalmologist with a right corneal ulcer and visual acuity of light perception (LP) in the right eye. The ulcer failed to heal with two weeks of topical lubrication, tobramycin, and cefazolin every 30 minutes as well as oflaxicin and moxifloxacin every four hours. The patient was then referred to us with a 2.8 mm × 3.5 mm right corneal ulcer with surrounding dense infiltrate, stromal haze, 2+ anterior chamber cells and flare but no hypopyon, and 4+ palpebral and bulbar conjunctival injection. The patient had no sensation in the right cornea as assessed with a cotton wisp, and visual acuity was 20/200 in the right eye. His medical history was significant for disseminated lymphangiomatosis, a disease characterized by diffuse or multifocal proliferation of lymphatic vessels within bone, soft tissue, and visceral organs,Citation3 diagnosed at the age of 14 years. In this case, lymphatic proliferation affected the boney structures surrounding Meckel’s (trigeminal) cave, through which the trigeminal nerve passes (see ).

The patient reported having a previous abrasion and infection of the right cornea 18 months prior to presentation that improved in one week after treatment with tobramycin and cefazolin ophthalmic drops. The history of disseminated lymphangiomatosis effacing Meckel’s (trigeminal) cave and corneal anesthesia led to a diagnosis of neurotrophic keratitis. Perhaps due to the multiple antibiotics the patient was taking upon referral, a culture for microbiology was negative for bacterial growth. The culture was also negative for fungus, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and Acanthamoeba. The patient was instructed to continue use of cefazolin every 30 minutes alternating with moxifloxacin every 30 minutes, tobramycin hourly, and he was also started on 100 mg oral doxycycline twice daily. The patient was urged to continue aggressive ocular lubrication during sleep and to use a moisture chamber at night. Finally, a bandage contact lens was placed.

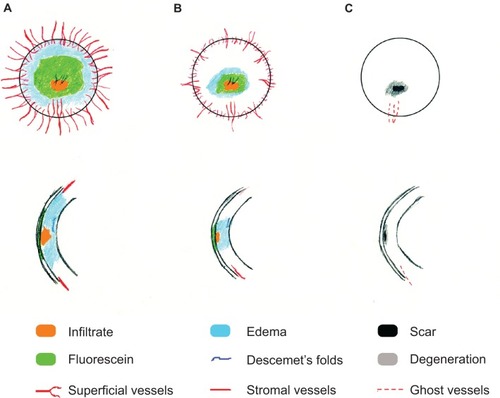

Due to difficulty in transportation to our clinic, the patient was followed locally. The ulcer worsened over the following two weeks, and fortified vancomycin was added to the treatment regimen. When we saw him again, he had a 9 mm epithelial defect (illustrated in ) with vision of light perception. The infiltrate was stable, and vancomycin was discontinued. The patient was placed on autologous serum drops and drawstring temporary tarsorrhaphy was employed.Citation4

Figure 2 Drawing of the patient’s cornea prior to A), ten days following B), and one month following C) drawstring temporary tarsorrhaphy. Drawings were constructed according to the methods described by Waring and Laibson.Citation9

Ten days later, the epithelial defect measured 2.5 × 2.5 mm with a decreasing infiltrate (illustrated in ). One month later, the epithelial defect had healed completely with resolution of the infiltrate (illustrated in ). Visual acuity was 20/40.

Discussion

A number of local ocular or systemic conditions that result in corneal anesthesia can cause neurotrophic keratitis. Damage to or compression of the trigeminal nerve from any source can eliminate corneal sensation and trigger the degenerative effects leading to destruction of the cornea. Here, we describe a case of neurotrophic keratitis with secondary infection in a patient with disseminated lymphangiomatosis affecting the boney structure surrounding the trigeminal ganglion. Broad-spectrum antibiotics and aggressive lubrication lead to resolution of the infection, and drawstring temporary tarsorrhaphy eventually healed the corneal ulcer.

Lymphangiomas are benign proliferations of well-differentiated lymphatic tissue characterized by increased numbers and complex arrangements of the lymph vessels.Citation5 Lymphangiomatosis occurs when multiple lymphangiomas are present, with disseminated lymphangiomatosis characterized by diffuse involvement of multiple tissues, especially bones and lungs. Lymphangiomatosis appears to be due to a developmental abnormality of the lymphatic system.Citation3,Citation6 Symptoms arise when progressive growth of the lymphangiomas compresses adjacent structures. In the 23-year-old male patient described here, lymphangiomatosis affected the bony structure of the skull likely leading to compression of the trigeminal nerve and subsequent anesthesia of the right cornea and face.

Three clinical stages of neurotrophic keratitis have been defined.Citation7,Citation8 Stage I is characterized by Rose Bengal staining of the palpebral conjunctivae, decreased tear breakup time, increased viscosity of tear mucus, punctate epithelial staining with fluorescein, and scattered small facets of dried epithelium (Gaule spots). Stage II involves acute loss of epithelium, a surrounding rim of loose epithelium, stromal edema, aqueous cell and flare, and the edges of the defect becoming smooth and rolled. Finally, stromal lysis, which may result in corneal perforation, defines stage III. We assign the present case as stage III given the severe corneal ulcer with early stromal melting.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of neurotrophic keratitis due to disseminated lymphangiomatosis. We hope that an awareness of this potentially disastrous blinding condition will lead to meticulous ocular examination, empathic patient education, and rigorous preventative care for these patients. This case also underscores the importance – in the setting of neurotrophic ulcer with secondary infectious keratitis – of appropriate therapies to aggressively address the neurotrophic component. Drawstring temporary tarsorrhaphy is an excellent procedure for this purpose allowing for close examination and frequent administration of topical medicines while effectively promoting epithelial healing.Citation4

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kelly E Knickelbein for drawing the corneal pathologies represented in . The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BoniniSRamaPOlziDLambiaseANeurotrophic keratitisEye20031798999514631406

- WrightPMackieIAMucus in the healthy and diseased eyeTrans Ophthalmol Soc U K19779717271369

- HilliardRIMcKendryJBPhillipsMJCongenital abnormalities of the lymphatic system: a new clinical classificationPediatrics1990869889942251036

- KitchensJKinderJOettingTThe drawstring temporary tarsorrhaphy techniqueArch Ophthalmol200212018719011831921

- FaulJLBerryGJColbyTVThoracic lymphangiomas, lymphangiectasis, lymphangiomatosis, and lymphatic dysplasia syndromeAm J Respir Crit Care Med20001611037104610712360

- LevineCPrimary disorders of the lymphatic vessels – a unified conceptJ Pediatr Surg1989242332402709285

- GroosEBJrNeurotrophic keratitisKrachmerJHMannisMJHollandEJCorneaSt. Louis, MOMosby1997213901347

- MackieIANeuroparalytic keratitisFraunfelderFRoyRHMeyerSMCurrent Ocular TherapyPhiladelphia, PAWB Saunders1995452454

- WaringGOLaibsonPRA systematic method of drawing corneal pathologic conditionsArch Ophthalmol19779515401542901266