Abstract

Hip fractures – which commonly lead to premature death, high rates of morbidity, or reduced life quality – have been the target of a voluminous amount of research for many years. But has the lifetime risk of incurring a hip fracture decreased sufficiently over the last decade or are high numbers of incident cases continuing to prevail, despite a large body of knowledge and a variety of contemporary preventive and refined surgical approaches? This review examines the extensive hip fracture literature published in the English language between 1980 and 2009 concerning hip fracture prevalence trends, and injury mechanisms. It also highlights the contemporary data concerning the personal and economic impact of the injury, plus potentially remediable risk factors underpinning the injury and ensuing disability. The goal was to examine if there is a continuing need to elucidate upon intervention points that might minimize the risk of incurring a hip fracture and its attendant consequences. Based on this information, it appears hip fractures remain a serious global health issue, despite some declines in the incidence rate of hip fractures among some women. Research also shows widespread regional, ethnic and diagnostic variations in hip fracture incidence trends. Key determinants of hip fractures include age, osteoporosis, and falls, but some determinants such as socioeconomic status, have not been well explored. It is concluded that while more research is needed, well-designed primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive efforts applied in both affluent as well as developing countries are desirable to reduce the present and future burden associated with hip fracture injuries. In this context, and in recognition of the considerable variation in manifestation and distribution, as well as risk factors underpinning hip fractures, well-crafted comprehensive, rather than single solutions, are strongly indicated in early rather than late adulthood.

Background to the problem

For many years hip fracture injuries have been identified as one of the most serious health care problems affecting older people. Much attention has consequently been placed on comprehensive efforts to reduce the incidence and severity of this condition. Indeed, some recent evidence suggests these efforts have met with some degree of success.Citation1,Citation2 However, the literature is unequivocal in this regard. Moreover, several current reports confirm hip fractures remain a leading cause of excessive morbidity, and premature mortality among older people.Citation3,Citation4 Thus, despite some positive downward trends in hip fracture incidence rates,Citation5 these may not be occurring universally or rapidly enough to offset the immense human and social costs projected to persist over the next several decades.Citation6

That is, given that hip fracture incidence rates rise exponentially with age, and that age specific hip fracture rates are rising for subsequent cohorts,Citation7 as longevity increases across the globe,Citation8 along with sedentary lifestyles that correlate with several key hip fracture determinants, it seems reasonable to speculate hip fractures will remain a serious world wide public health problem as proposed by Wehren and Magaziner in 2003.Citation6 To this end, this paper explores if there is sufficient current support for this premise, and if so, whether concerted efforts towards prevention are desirable. By analogy it also explores whether long-term costs of this health problem of nearly US$9 billion dollars in 1995Citation6 are also likely to rise, first, because an increasing body of older people survive after hip fracture injuries as a result of better acute care. Second, because these survivors commonly encounter various degrees of progressive disability that require long-term care and extensive ongoing services.Citation6 Third, as more adults reach the age of 85 years, these adults who are commonly in precarious health or recover more slowly when injured than younger adults, are 10–15 times more likely than those younger than 85 years to fracture a hip.Citation9

It is the author’s view that hip fractures will continue to be of substantive importance to public health planners, particularly if as predicted, a vast majority of these injuries in the 21st century will occur in developing countriesCitation10 where the resources to deal with this problem are likely to be somewhat undeveloped, underfunded and technologically suboptimal. Another related issue is that a high percentage of hip fractures are linked with osteoporosis, which is an escalating global problem. Additionally, hip fractures, the most catastrophic complication of osteoporosis, continue to result in significant mortality and morbidity rates despite the increasing availability of effective preventative agents.Citation11 Lastly, the costs of care for this debilitating injury are immense because they are not limited solely to the costs of functional disability and increased death rates,Citation8 but commonly to several other factors including, a loss of the ability of the injured adult to function independently, the related costs of nursing care, rehabilitation care, and need for one or more surgeries. Thus, rather than becoming complacent given some progress in reducing anticipated rates of hip fracture in some regions, continued vigilance, plus the implementation of widespread cost-effective preventive strategies against hip fractures, as stressed by Wilson and WallaceCitation8 and Haleem and colleaguesCitation3 remain strongly indicated.

However, to secure support for efforts to prevent hip fractures and their debilitating outcomes within an economic climate that often demands service cutbacks and fiscal restraint, and a science base that does not always stress the economic and social value of prevention, the rationale for this approach must be clearly depicted. That is, a clear case must first be made for why the issue merits specific attention, and thereafter, for what specific strategies might be set in place or emphasized to minimize the related human and economic impact.

To this end, the present review reports pertinent data from the available peer-reviewed literature detailing the distribution and possible casual factors related to hip fractures published in the peer-reviewed literature over the last 30 years. Also reported are some findings regarding second hip fractures, an often overlooked, albeit important, associated outcome of the initial injury. As well, information depicting the economic and human impact of this condition, a topic not often detailed in the related literature is presented. Finally, some recommendations for improving our understanding of this health condition including potential preventive directives against first and second hip fractures, and their debilitating consequences are provided.

Methods

The literature reviewed was primarily accessed from an array of research based articles written in English, and located in the Medline and PubMed databases and published between 1980–2009. Key terms used were: ‘hip fracture’, ‘epidemiology’, ‘incidence’, ‘prevalence’, ‘risk factors’. All related articles that reported on hip fracture rehabilitation or surgery were excluded from the report. The pertinent data was carefully examined and then categorized into the key themes of interest: distribution and prevalence, outcomes and risk factors. In terms of the author’s aims, as well as space limitations, only those risk factors deemed both consistently salient and amenable to prevention are highlighted. The magnitude and extent of the disability is included to draw attention to the need for reducing the incidence and severity of this debilitating condition. In keeping with the broad aims of the paper, the review approach adopted was largely a narrative one, and an attempt was made to simplify and tabulate themes of importance. Based on the high numbers of reports from well known research establishments and researchers, and the consistency of many reports from diverse laboratories and regions, regardless of study design, an assumption was made that the reports reviewed provided consistently valid conclusions.

Descriptive epidemiology

Hip fracture trends 1970–2009

While somewhat variable, data published since the early 1990s describing the occurrence of hip fractures across the globe has generally shown the age-adjusted incidence of this injury is increasingCitation3,Citation6 or is projected to increase.Citation12 Accordingly, it was initially predicted that if there was a steady increase in the numbers of United States residents reaching the age of 85 years or older,Citation13 the numbers of elderly at risk for a hip fracture would double by 2007. That is, the total number of hip fracture cases in later life was not only expected to remain significant, but was projected to rise substantively.Citation8 At the same time, this age-associated trend in longevity was not only influencing hip fracture risk in the United States, but was also evident in The People’s Republic of China where hip fracture rates, once amongst the lowest in the world compared with more affluent countries,Citation14 increased by 34% for women and 33% for men between 1988 to 1992.Citation15 Similarly, in Finland, the whole population incidence rate increased approximately three fold between 1970 and 1991 with respect to both genders,Citation16 and between 1970 and 1997, the age-specific incidence of hip fractures increased in all age groups.Citation17

Likewise, linear increases of age-adjusted fracture incidences for men and women were reported in the Netherlands between 1972–1987 and the analysis also showed that this age-specific incidence increase was higher than that of earlier birth cohorts.Citation18 Similar trends were noted in Japan where hip fracture incidence rates for both genders were shown to increase exponentially with age after the age of 70 years with an annual incidence among women aged 85 years and older of 2,000 cases.Citation19 Rates in Sweden from 1966–1986 were also found to increase from 3.3 per 1,000 inhabitants to 5.1 for persons aged more than 50 years, and almost doubled in persons aged more than 80 years, with a proportional increase that was greatest for men and city dwellers.Citation20

Indeed, despite some evidence of declining hip fracture incidence rates in North AmericaCitation21 and among some Swiss women,Citation22 as people live longer, and the average age of the hip fracture patient continues to increase from 73–79 years,Citation3 it is possible the total number of hip fractures in the world, estimated at 1.7 million in 1990Citation16 will still rise exponentially to 6.3 million by the year 2050.Citation23 In support of this argument, it has been noted that even in those regions of the United States where downturns in hip fracture incidence rates have been recorded,Citation21 there are still increasing numbers of adults living to higher ages. In addition, rates of downturn over a 10-year period from 1991–2000Citation22 may only reflect declines among standardized hip fracture incidence rates of institution-dwelling women, rather than a general reversal in secular trends.Citation5 Further, the fact that more older United States adults had low femoral neck bone mass density in 2005–2006 than in 1988–1994, implies the number of United States adults at risk for future hip fractures will remain high.Citation24 Other estimates are that there will be a sevenfold increase between the present time and 2050 in BelgiumCitation25 that will be greater in men than women if no comprehensive preventive policy is set up, and marked increases in Asia where the highest absolute increment in the elderly population will be observed.Citation26

Moreover, high incidence rates continue to prevail in some northern Europe regionsCitation16 and these are expected to rise.Citation6 In Germany, for example, a call for improving and developing prevention strategies against hip fractures attributable to osteoporosis currently prevails because 2050 projections of this condition are expected to increase costs exponentially between 2020 and 2050 due to changing demographics.Citation27 In Australia, the number of hip fractures is similarly expected to double over 29 years and quadruple in 56 years.Citation28 Furthermore, data published in 2008 covering the years 1994–2006 in Austria, showed that in contrast to findings in some countries, there has been no levelling-off or downward trend of hip fracture incidence in the Austrian elderly population. After adjusting for age and gender, the fracture increase, while small was significant and rose numerically from 11,694 in 1994 to 15,987 in 2006.Citation29

Summary

While many studies conducted in the 1990s predicted increasing hip fracture prevalence rates in the 21st century, the current literature reveals some levelling off of these rates, especially among individuals at risk for osteoporosis. However, as the number of older adults living to higher ages increases globally, the total numbers of hip fracture cases and their related expenditures are likely to rise substantively.Citation27 Moreover, even if some of the aforementioned data do not take into account more recent bone sparing pharmacologic interventionsCitation3 and other experimental therapies that may prevent hip bone loss,Citation30 some published data reporting an age-specific flattening of the incidence of hip fractures,Citation31,Citation32 may be underestimates because they often exclude hip fracture injury cases or injuries that have occurred have not been accurately coded.Citation3

Hip fracture incidence may also be hard to capture with precision because rates may vary depending on seasonality,Citation33 geography,Citation34–Citation37 and factors other than aging.Citation34 These include health status,Citation38 ethnicity,Citation38,Citation39 gender,Citation40–Citation44 neuromuscular status,Citation45 extent of urbanization,Citation46 along with year of immigration to the United States,Citation47 the availability, nature, and potency of current therapeutic and/or preventive measures.Citation38,Citation48 The method of deducing trends in hip fracture and their results can also vary substantively with the model used as demonstrated by Fisher and colleagues in the Australian context.Citation48 In addition, along with the large variation in the age, gender, and geographic distribution of hip fractures within and across countries,Citation44,Citation49,Citation50 especially challenging in efforts to effectively capture the true global burden of hip fractures is the fact there are three distinctive hip fracture sub-types, each with potentially different risk factor profilesCitation51–Citation53 and prevalence rates.Citation54–Citation60

Although it is not possible to prove or disprove, it seems that the strong correlation between aging and hip fractures favors the prediction that hip fracture incidence rates will rise by 1%–3% per year in most areas of the world for both men and women in the years to come.Citation61,Citation62 In addition to the aging factor, a widespread lack of awareness of the importance of osteoporosis persists and prevents the widespread use of drugs with anti-fracture efficacy.Citation63 Moreover, because not all hip fractures are related to osteoporosis,Citation62,Citation64 but these risk factors may not be addressed or followed-up at all adequately,Citation64 the health care system and societal costs of hip fractures are projected to increase if concerted preventive efforts with ‘new, effective and widely applicable strategies’ are not forthcoming.Citation65–Citation67 These projected costs include, but are not limited to, avoidable deaths, disability, and rising costs due to higher numbers of discharges of post-hip fracture patients to continuing care institutions.Citation68

In addition to the above mentioned factors, adults who sustain intertrochanteric fractures, whose numbers increase progressively with age, experience higher mortality, morbidity, and costs than those of cervical fractures.Citation16 As well, despite declining hip fracture reoccurrence rates greater than anticipated in recent years,Citation69 adults who have sustained a hip fracture are commonly susceptible to subsequent hip fractures. That is, a second hip fracture, which may be in the same location with a tendency to greater displacement or instability occurs about 6% of the time and within a four-year period post-fracture.Citation70 Further, if DolkCitation71 is correct, the frequency of sustaining two hip fractures over the course of an individual’s lifetime could reach 20%. Furthermore, because new hip fractures may occur on the same side as well on the opposite side to an initial fracture, it may be possible to sustain three hip fractures over time, and according to Shroder and colleaguesCitation72 the risk of incurring a third hip fracture per 1,000 men is 8.6 and 9.8 per 1000 women, per year.

Prevention here is key again because there is no well defined pattern to clearly predict who is at risk, because contributory risk factors other than osteoporosis,Citation73 as well as untreated osteoporosis after the first fracture can be implicated in mediating two episodes of fragility fractures.Citation74 Other data show the incidence rate for second hip fractures can be higher than that of first hip fractures,Citation75 and as discussed by Berry and colleaguesCitation76 one year mortality rates can be approximately 10% higher following a second hip fracture than an initial fracture.Citation76

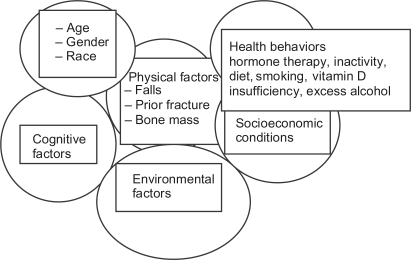

However, pursuing the means to prevent first and second hip fractures is very challenging, because as outlined above, and reiterated by Thomas and colleagues,Citation77 the risk of hip fracture, which rises 100–1000-fold over six decades of age is only explained in a minor way by declining bone mineral density. Several other risk factors for hip fractures that may serve as additional therapeutic targets may be helpful for reducing the rate and severity of the hip fracture injury and its costs (see ) have been the focus of a large volume of research. The predominant determinants that have been studied are discussed below and were selected as representative of those deemed consistently important as well as amenable to intervention.

Table 1 Summary of studies depicting high monetary costs of treating hip fracture cases in different countries

Risk factors for hip fracture

Biomechanical factors

Falls

In the early 1990s, research by Hayes and colleaguesCitation65 demonstrated that over 90% of hip fractures are associated with falls. Since that time, an additional body of evidence has revealed a strong association between several diverse falls-related mediators and hip fracture injuries that may be useful intervention points in efforts to reduce hip fracture incidence rates. These include: balance impairments,Citation45,Citation78 neuromuscular and musculoskeletal impairments,Citation79 fall type,Citation80 fall severity, and fall speed.Citation65 In addition, the presence of ineffective or suboptimal protective responses, along with age-associated strength decreases,Citation81 cognitive impairment,Citation82 and fear of falling, a serious disorder in older people, may increase the risk of falling and fracturing the hip.Citation83 Declines in visual perception, proprioception and/or transient circulatory insufficiencies,Citation68,Citation84 as well as impaired sensory-motor integration functioning,Citation85 and unexpected perturbations are additional determinants.

Physical inactivity

A sizeable body of research over the last 30 years has also shown physically inactive elderly adults are more than twice as likely as active adults to be at risk for hip fractures (see ).Citation35,Citation86–Citation89 Indeed, due to its highly negative impact on bone health, muscle physiology, muscle mass, overall health status, and on vitamin D exposure,Citation90,Citation91 physical inactivity is currently proffered as the most salient explanatory factor for the increasingly high hip fracture rates reported by developing countries, as well as many first-world countries.Citation85

Table 2 Research evidence showing a strong relationship between physical activity participation and hip fracture risk in prospective studies

Muscle weakness

Several researchers have concluded that muscle weakness, commonly associated with slower reflex responsesCitation83 can significantly increase the chances of falling due to unexpected perturbations, thus heightening the risk of fracturing a hip.Citation65,Citation92,Citation93 Related research shows low levels of muscular strength can also heighten the risk of sustaining a hip fractureCitation88 because of its long term negative impact on bone densityCitation94 and muscle shock absorbing capacity.Citation95 Not surprisingly, an increased risk of falling and sustaining a hip fracture has been specifically noted in association with muscular impairments at the ankle,Citation78 hip and knee,Citation59,Citation85,Citation96,Citation97 low body strength in general,Citation89,Citation96 and lower limb dysfunction.Citation98

Body anthropometrics

While body height, a nonmodifiable factor, may predispose towards a hip fracture,Citation80,Citation94,Citation99–Citation106 as outlined in , there is a consistent association between the presence of a low body mass and an increased fracture risk,Citation106 especially among Caucasian men,Citation107 after the age of 50 years,Citation108 which may be amenable to intervention. This association is especially strong in individuals with low bone mineral density,Citation109 and where a weight loss relative to maximal weight exceeds 10% of body weight.Citation106,Citation110 Moreover, older women with smaller body size are likely to be at high risk of fracturing their hips because of their potentially lower bone mineral density,Citation111 as well as less soft tissue coverage of their hips than women of normal body weight.Citation46,Citation112

Table 3 Summary of prospective studies examining the association between body mass and hip fractures and showing equivocal results

However, Parker and colleaguesCitation113 found overall body size, rather than body composition of the femoral gluteal area predicted the occurrence of a hip fracture in a cohort of postmenopausal women, and although most people who fracture their hips could be classified as being thin, Cumming and KlinebergCitation114 and Maffulli and colleaguesCitation115 reported their patients with hip fractures tended to be overweight. Dretakis and ChristadoulouCitation116 too, noted similar rates of overweight and underweight hip fracture cases among their 373 patients. Similarly, when patients with severe dementia were excluded, Bean and colleaguesCitation92 found thinness was not necessarily associated with hip fracture. Heavier individuals may also be expected to have low levels of sex hormone-binding globulin, a prevalent finding among women with recent hip fractures,Citation117 and several comorbid conditions that are known risk factors for falling, plus medical conditions associated with osteoporosis.Citation118

Bone structure

Although hip fracture is the most serious consequence of osteoporosis,Citation119 the literature is inconsistent in demonstrating diminished bone density is universally predictive of a future hip fracture. For example, while bone density measures at the femoral neck were found to be strongly predictive of hip fractures in both men and women in one study,Citation120 several others have reported a considerable overlap in bone densities between hip fracture patients and age- and gender-matched controls after the age of 70 years, or no significant risk.Citation87–Citation89,Citation93 In addition, Wei and colleaguesCitation119 found the effect of significant risk factors for hip fracture of direct hip impact, previous stroke, sideways fall, decreased functional mobility, or low body mass remained the same regardless of femoral neck bone density. However, bone mineral density was significantly correlated with functional mobility and low body mass, which together are predictive of falls that can result in hip fractures. It has also been observed that bone mineral density is a weaker predictor of intertrochanteric hip fractures than femoral neck fractures.Citation121 Other data reveal comparable osteoporotic indices between cases and controls,Citation122 and that hip fracture cases were not more osteopenic than age- and gender-matched controls.Citation123 Moreover, Asians, who have similar, or lower bone mineral densities than Caucasians, and partake in diets low in calcium, have a low incidence rate of hip fracture, especially in women.Citation14 Mathematical models too, cannot account for the exponential rise in hip fractures with age solely on the basis of bone density levels.Citation124 Further, individuals with osteoarthritis and higher bone density levels than the norm are not protected against hip fractures.Citation125

Such findings strongly suggest factors other than low bone mineral density and bone mass contribute to the risk of hip fractures. These factors include but are not limited to those that increase the risk for falling, the property of the fall surface, the geometry of the hip, body size, the degree of soft tissue coverage around the hip, and the presence of poor muscle responsiveness and muscle weakness,Citation46,Citation85,Citation93,Citation97,Citation113,Citation114,Citation122 (see ).

Table 4 Selected studies covering a 20 year period describing hip fracture injury risk factors other than bone mineral density and bone mass that could serve as risk assessment and risk reduction intervention points

Clinical

Chronic health conditions

Many chronic illnesses associated with aging, in particular, arthritis and Parkinson’s disease, substantially increase the risk of falling, and hence the likelihood of incurring a hip fracture.Citation126–Citation128 In addition, arrhythmias, postural hypertension, and peripheral neuropathies may increase the risk of falls and hip fractures,Citation67 as may the presence of Alzheimer’s diseaseCitation129 and other neurological conditions, such as stroke.Citation130 Diabetes mellitus,Citation131 hyperthyroidism,Citation132 and medical conditions associated with osteoporosis,Citation133 other forms of disability associated with the risk of falling,Citation133 use of walking aids,Citation134 as well as prolonged immobilization,Citation46 may also increase the risk of sustaining a hip fracture. Rehospitalization after hip fracture may also be influenced negatively by the presence of comorbid clinical problems,Citation135 as may outcomes of acute hip fracture if multiple problems exist, especially respiratory disease or malignancy.Citation136

Impaired cognition

In addition to the aforementioned factors, depression, and/or the presence of one or more cognitive impairments may heighten the risk of falling and fracturing a hip.Citation94,Citation126,Citation128,Citation135,Citation137–Citation139,Citation144–Citation146 Similarly, a prevailing cognitive impairment may impact the effectiveness of postoperative rehabilitation strategies after hip fracture surgery,Citation140 and increases the risk of falling after a hip fracture.Citation141 The individual with mental deterioration who trips and fails to break their fall may be especially vulnerable to fracturing the hip if already weak and osteoporotic due to poor nutritional status.Citation142

Impaired vision

Impaired vision may be an independent risk factor for hip fracture.Citation83,Citation126,Citation143 Evidence for this has been provided by Ivers and colleagues in a prospective study of 3,654 adults aged 49 years or older for five yearsCitation143 and by Ivers and colleaguesCitation144 in a case-control study of 911 cases and 910 controls aged 60 years or older. In the latter study, the population attributable risk of hip fracture due to poor visual acuity or stereopsis, vision wherein two separate images from two eyes are successfully combined into one image in the brain, was 40%. In their more recent prospective study, Ivers and colleagues found visual impairment to be strongly associated with risk of hip fracture in the next two years. Pfister and colleaguesCitation145 also noted impaired vision was prevalent among women aged 50 years and older with proximal hip fractures. Impaired vision has also been associated with hip fractures occurring in the hospitalCitation146 and among the Framingham Study Cohort,Citation147 where those with poor vision in one or both eyes had an elevated fracture risk and those with moderately impaired vision in one eye and good vision in the other had a higher risk of fracture than those with a similar degree of binocular impairment.

Medications, alcohol, and chemical substances

Although Rashiq and Logan,Citation148 who examined the role of drugs in hip fractures found that with the exception of antibiotics, fracture risk was lower in those taking drugs, drugs reported to be related to falls that may lead to a hip fracture include: cimetidine, psychotropic anxiolytic/hypnotic drugs, barbiturates (which may also decrease bone quality), opioid analgesics, and antihypertensives,Citation126,Citation137 long-acting benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, and caffeine.Citation89 Tranquillizers, sedatives, and exposure to any of the three classes of antidepressants is associated with a significant increase in the risk of falling and sustaining a hip fracture.Citation66,Citation67,Citation149 In particular, long-acting sedatives and alcohol that can slow reaction time may partly explain the increased risk of hip fractures associated with use of sedatives and regular alcohol intake.Citation124,Citation136,Citation134 Alternately, alcohol abuse may result in a negative bone balance,Citation150 decreased balance, impaired gait, and heightened risk-taking behaviors.Citation151 Additionally, tricyclic antidepressants may increase the risk for hip fracture due to their detrimental cardiovascular side-effects, and/or their side-effects of sedation and confusion.Citation152 Use of corticosteroids is also a documented risk factor for hip fracture,Citation46 and may reflect the detrimental effect of corticosteroids on bone mineral density, as may levothyroxine when used by males.Citation153 Smoking cigarettes or a pipe,Citation98 and the consumption of tea, and fluorine concentrations over 0.11 mg per literCitation154 also increases the risk of hip fracture,Citation17,Citation98 as do benzodiazepines.Citation155

Environmental factors

Although many preventive programs against hip fracture focus on environmental factors, of the many factors that can influence hip fracture risk, Norton and colleaguesCitation156 found only 25% of falls that could lead to a hip fracture were associated with an environmental hazard. Further, while environmental factors may undoubtedly be a precursor to injurious fallsCitation157 a study by Allander and colleaguesCitation158 found a very low correlation between the number of risk factors of the faller and the environment.

In summary, age, a variety of age-associated physiological changes, low levels of physical activity participation, poor nutrition practices, and some forms of medication may impact two crucial determinants of hip fracture, namely femoral bone strength, and the propensity to falls. In addition, declining muscle, cognitive, visual and neural reflex responses, are likely to impact the propensity of older adults towards hip fracture injuries.Citation45 The overlapping relationship between these factors as portrayed in are also likely to impact recurrent falls, and second or new hip fractures following a hip fractureCitation159 and may also explain partly why hip fracture incidence rates vary, and remain substantive in many regions (see ).

Figure 1 Model of key factors implicated in hip fracture injury with intervention points highlighted.

Source: Kanis, Johansson, Oden, et al.Citation189

Table 5 Contemporary studies that show evidence of rising hip fracture incidence rates in a number of venues worldwide, despite declining rates in others

Conversely, a better understanding of these factors may help in reducing the persistent and debilitating outcomes of hip fracture injuries portrayed in .

Table 6 Chronology of studies over a 20 year period consistently describing poor outcomes after hip fracture, regardless of contemporary management and rehabilitation strategies

Discussion

As outlined in the body of the paper, despite some successes in reversing predicted hip fracture trends in some regions, many current reports continue to describe increasing or rising hip fracture trends in other regions (see ). Although it is consequently impossible to determine if the projected global incidence of hip fracture cases is likely to reach 4.5 million by 2050 as predicted,Citation4 it seems fair to anticipate increases in some regions.

For example, hip fracture incidence rate increases, rather than decreases are expected in Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa as a result of increases in their elderly populations.Citation16 Similarly, hip fractures in people aged 60 years and older living in central Australia are predicted to almost double by 2011 and increase 2.5-fold and 5.4-fold by 2021 and 2051, respectively.Citation160 A current Norwegian study has further revealed regions of the country where high lifetime absolute fracture risk rates among adults aged 25 years and older are predicted based on 1995–2004 data.Citation161 Another related report showed annual decreases in New York State between 1985 and 1996 were not uniform in all age, gender, and race groups.Citation162 In addition, in 2008, Auron-Gomez andCitation163 from the Cleveland Clinic stated the incidence of hip fractures in the United States of approximately 250,000 per year is expected to double in 30 years.

Moreover, as outlined by Abrahamsen and colleaguesCitation164 and summarized in , even in regions where hip fracture rates are declining, the very stark human impact of sustaining one or more hip fractures supports a continued global effort to minimize this burden. As well, the economic consequences of hip fracture continue to rise, despite declining lengths of hospital stay.Citation66

However, because many variations in hip fracture prevalence rates exist, and multiple, rather than single risk factors preside interventions to reduce their prevalence are difficult to develop without further research.Citation44 In addition, the correlation between hip fractures and low bone density is not a perfectly positive one,Citation165 and thus more insightful studies to better elucidate the etiology of hip fracture variants is indicated as outlined almost 20 years ago by Cummings and Nevitt.Citation124 In this regard, as Leibson and colleaguesCitation64 have pointed out, hip fracture prophylaxis and its potential savings may be overestimated by studies that fail to consider differential risk, mortality and long-term follow-up data. Moreover, even though Chang and colleaguesCitation166 emphasized the need for early osteoporosis prevention in both men and women because over 48% of hip fractures in men and 66% of those in a white population in Australia were found to incur hip fractures before the ages of 80 and 85 years, respectively, Lippuner and colleaguesCitation63,Citation64 note there is a significant lack of awareness of this disease and its consequences and this warrants attention. In addition, there are few carefully designed prospective studies that examine the nature of the age-specific increase in incidence, and whether this is due to changes in the etiology of the fracture, and not just the consequence of demographic change as postulated by Boyce and Vessey in 1985.Citation167

What is known, is that to prevent unwarranted increases in hip fracture incidence rates and their secondary complications and costs, careful consideration of their multifactorial causation is imperative.Citation3,Citation36,Citation162,Citation168 Other promising strategies include the development of routine risk-factor assessments for older adults,Citation169 improved study designs that examine the predictive role of novel factors in mediating hip fractures,Citation40 the reduction of remediable visual, hearing, and combined impairments among aging cohorts,Citation170 and encouraging the avoidance of excessive alcohol, and psychotic drugs among people at risk for first or second hip fractures. Factors that may be especially useful to examine regularly during annual check ups are listed in Box 1 and others warranting attention include those potential predictors outlined by Wilson and colleaguesCitation59 such as health insurance status, and educational level.

In the context of preventing secondary disability and poor outcomes, careful analyses of the type of fracture involved, the etiology of the fracture, and the appropriate timing of tailored interventions may be crucial.Citation160,Citation171 Identifying risk factors that explain gender differences in risk and outcome,Citation171 as well regional variations could potentially impact hip fracture incidence rates as well.Citation162 Examining the role of the health care system in the context of explaining hip fracture variants and the prevailing degree of health or disability may also be helpful.

Examine:

Balance capacity

Bone density

Cognitive status

Drug usage, medications such as steroids

Presence of comorbid conditions

Falls history

Overall health and nutritional status

Lifestyle, nutritional practices, and activity levels

Muscle strength and reflex responsiveness

Proprioception

Tobacco usage

Walking ability

Vision

Homocysteine levelsCitation229

Do careful follow-up of proximal humeral fracture casesCitation230

Identify older adults at risk for falls due to:

Fear of falling

Poor housing

Lack of activity opportunities

Poor nutrition

Unstable or poor mental status

Emotional distressCitation164

Adverse neurological status

Medication mix

Alcohol problem

Age

Prior falls history

Recent hospitalization

Unsafe housing or environment

In summary, because hip fracture risk rises exponentially with age,Citation44,Citation172 hip fractures are likely to remain an important public health problem despite declining incidence trends in some regions.Citation159 Indeed, high numbers of aging adults will continue to be impacted globally by this injury,Citation160,Citation173 because by 2031 approximately 45% of all hip fracture cases will be aged 85 years or older.Citation164

As well, regardless of progress in reducing hip fracture incidence in some regions, high levels of disability among survivors persists, and a high proportion of hip fracture cases, particularly menCitation174,Citation175 and those older than 75 years, continue to die at increased rates within the first three to six months of their injury.Citation171 Those with comorbidities,Citation140,Citation175, Citation176,Citation178 and poor mental status – which are likely to continue to be consistent features among aging populations – are especially vulnerable.Citation133,Citation178 Other factors that predict poor post-hip fracture outcomes are less than optimal follow-up of survivors,Citation179 limited prefracture mobility,Citation180–Citation182 a variety of psychosocial factors,Citation183 the patient’s general medical condition,Citation184,Citation178 balance status,Citation185 their propensity towards falling,Citation186 and eye and neurological diseases.Citation187

To offset the predicted hip fracture burden,Citation35 careful study of hip fracture variants,Citation164 collecting and carefully analyzing routinely collected dataCitation188 for evidence of clinical risk factors other than bone mineral density,Citation165,Citation189 establishing a standard method for determining hip fracture incidence,Citation50 and more vigilance in secondary prevention contexts is recommended.Citation3 As well, more epidemiological studies to elucidate trends in hip fracture occurrences due to demographics, age, gender, ethnicity,Citation6 health care setting,Citation168,Citation190 and health care system diversityCitation166 are desirable. Public health organizations in developing countries are especially encouraged to develop innovative preventive strategies,Citation191 and high risk adults, especially those with comorbid diseases,Citation178 low body mass and low income,Citation192 and elders in institutions at high risk for first and second hip fractures, excess mortality and poor outcomes,Citation168,Citation171,Citation190,Citation193 should be targeted.Citation50 In addition, men who appear increasingly vulnerable to hip fractureCitation43 should be targeted.Citation194 Aging adults should have access to timely preventive strategies,Citation159 including osteoporosis prevention,Citation166 and be encouraged to maintain physically active lifestyles, and appropriate body weights.Citation119,Citation195

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LeslieWDO’DonnellSJeanSOsteoporosis Surveillance Expert Working GroupTrends in hip fracture rates in CanadaJAMA200930288388919706862

- NievesJWBilezikianJPLaneJMFragility fractures of the hip and femur: incidence and patient characteristicsOsteoporos Int2009530[Epub ahead of print].

- HaleemSLutchmanLMayahiRGriceJEParkerMJMortality following hip fracture: trends and geographical variations over the last 40 yearsInjury2008391157116318653186

- ParkerMJohansenAClinical review. Hip fractureBMJ2006333273016809710

- GuilleyBChevallyTHerrmannFReversal of the hip fracture secular trend is related to a decrease in the incidence in institution dwelling elderly womenOsteoporos Int2008191741174718484149

- WehrenLEMagazinerJHip fracture: risk factors and outcomesCurr Osteoporos Reports200317885

- SamelsonEJZhangYKielDPHannanMTFelsonDTEffect of birth cohort on risk of hip fracture: age-specific incidence rates in the Framingham StudyAm J Public Health20029285886211988460

- WilsonRTWallaceRBTrends in hip fracture incidence in young and older adultsAm J Public Health2007971734173517761556

- ScottJCOsteoporosis and hip fracturesRheum Dis Clin North Am1990167177402217966

- ClarkPLaviellePFranco-MarinaFIncidence rates and life-time risk of hip fractures in Mexicans over 50 years of age: a population-based studyOsteoporos Int2005162025203016133641

- DemontieroODuqueGOnce-yearly zoledronic acid in hip fracture preventionClin Interv Aging2009415316419503777

- LyonsARClinical outcomes and treatment of hip fracturesAm J Med199710351S64S9302897

- SuzmanRMThe Older OldNew York, NYOxford University Press1992

- YanLZhouBPrenticeAWangXGoldenMHNEpidemiological study of hip fracture in Shenyang, People’s Republic of ChinaBone1999241511559951786

- XuLLuAZhaoXChenXCummingsSRVery low rates of hip fracture in Beijing, People’s Republic of China. The Beijing Osteoporosis projectAm J Epidemiol19961449019078890668

- KannusPParkkariJSievanenHEpidemiology of hip fracturesBone19961857S63S8717549

- KannusPNiemiSParkkariJPalvanenMVuoriIJarvinenMHip fractures in Finland between 1970 and 1997 and predictions for the futureLancet199935380280510459962

- BoereboomFTRaymakersJAde GrootRRDuursmaSAEpidemiology of hip fractures in the Netherlands: women compared with menOsteoporosis Int19922279284

- HaginoHMuscle and bone health as a risk factor of fall among the elderly. Epidemiology of falls and fracturesClin Calcium20081874775318515942

- JarnloGBHip fracture patients. Background factors and functionScandinav J Rehabil Med1991Suppl 24131

- MeltonLJIIIKearnsAEAtkinsonEJSecular trends in hip fracture incidence and recurrenceOsteoporosis Int200920687694

- ChevalleyTGuilleyEHerrmannFRHoffmeyerPRapinCHRizzoliRIncidence of hip fracture over a 10-year period (1991–2000): reversal of a secular trendBone2007401284128917292683

- CooperCCampionGMeltonLJHip fractures in the elderly: a worldwide projectionOsteoporos Int199222852891421796

- LookerACMeltonLJHarrisTBBorrudLGShepherdJAPrevalence and trends in low femur bone density among older US adults: NHANES 2005–2006 compared with NHANES III daggerJ Bone Miner Res200976[Epub ahead of print].

- ReginsterJYGilletPGossetCSecular increase in the incidence of hip fractures in Belgium between 1984 and 1996: need for a concerted public health strategyBull World Health Org20017994294611693976

- GullbergBJohnellOKanisJAWorldwide projections for hip fractureOsteoporos Int199774074139425497

- KonnopkaAJeruselNKönigHHThe health and economic consequences of osteopenia- and osteoporosis-attributable hip fractures in Germany: estimation for 2002 and projection until 2050Osteoporos Int2009201117112919048180

- SandersKMNicholsonGCUgoniAMPascoJASeemanEKotowiczMAHealth burden of hip and other fractures in Australia beyond 2000. Projections based on the Geelong Osteoporosis studyMed J Aust199917046747010376021

- MannEIcksAHaastertBMeyerGHip fracture incidence in the elderly in Austria: an epidemiological study covering the years 1994 to 2006BMC Geriatr200883519105814

- LarkMWJamesIENovel bone antiresorptive approachesCurr Opinion Pharmacol20022330337

- HuuskoTMKarppiPAvikainenVKautiainenHSulkavaRThe changing picture of hip fractures: dramatic change in age distribution and no change in age-adjusted incidence within 10 years in central FinlandBone19992425725910071919

- LauEMCooperCFungHLamDTsangKKHip fracture in Hong Kong over the last decade-a comparison with the UKJ Public Health Med19992124925010528950

- Alvarez-NebredaMLJimenezABRodriguezPSerraJAEpidemiology of hip fracture in the elderly in SpainBone20084227828518037366

- PaspatiIGalanosALyritisGPHip fracture epidemiology in Greece during 1977–1992Calc Tissue Int199862542547

- LyritisGPEpidemiology of hip fracture: the MEDOS studyOsteoporos Int1996Suppl 3S11S15

- MeltonLJEpidemiology of hip fractures: implications of the exponential increase with ageBone199618121S125S8777076

- HiebertRAharonoffGBCaplaELTemporal and geographic variation in hip fracture rates for people aged 65 or older, New York State, 1985–1996Am J Orthop20053425225515954693

- EspinoDVSilva RossJOakesSLBechoJWoodRCCharacteristics of hip fractures among hospitalized elder Mexican American Black and White Medicare beneficiaries in the Southwestern United StatesAging Clin Exp Res20082034444818852548

- KohLKSawSMLeeJJLeongKHLeeJHip fracture incidence rates in Singapore 1991–1998Osteoporos Int20011231131811420781

- VestergaardPRejnmarkLMosekildeLStrongly increasing incidence of hip fractures in Denmark from 1977 to 1999Ugeskr Laeger20081862162318367043

- FieldenJPurdieGHorneGDevanePHip fracture incidence in New Zealand, revisitedN Z Med J20011315415611400921

- LöfmanOBerglundKLarssonLTossGChanges in hip fracture epidemiology: redistribution between ages, genders and fracture typesOsteoporos Int200213182511878451

- LimSKooBKLeeEJIncidence of hip fractures in KoreaJ Bone Miner Metab20082640040518600408

- MemonAPospulaWMTantawyAYIncidence of hip fracture in KuwaitInt J Epidemiol1998278608659839744

- BoonenSBroosPDequekerJAge-related factors in the pathogenesis of senile (Type II) femoral neck fractures. An integrated viewAm J Orthop1996251982048775696

- LauEMLeeJkSuriwongpaisalPThe incidence of hip fracture in four Asian countries; the Asian Osteoporosis Study (AOS)Osteoporos Int20011223924311315243

- LauderdaleDSJacobsenSJFurnerSEHip fracture incidence among elderly Asian-American populationsAm J Epidemiol1997155025099290511

- FisherAAOBrienEDDavisMWTrends in hip fracture in Australia: possible impact of bisphosphonates and hormone replacement therapyBone20094524625319409518

- FinsenVJohnsenLGTranøGHansenBSneveKSHip fracture incidence in central Norway: a followup studyClin Orthop Relat Res200441917317815021150

- CerwinskiEKanisJATrybulecBJohanssonHBorowyPOsieleniecJThe incidence and risk of hip fracture in PolandOsteoporosis Int20092013631367

- DuboeufFHansDSchottAMDifferent morphometric and densitometric parametrs predict cervical and trochanteric hip fracture: the EPIDOS StudyJ Bone Miner Res199712189519029383694

- MichelsonJDMyersAJinnahRCoxQVan NattaMEpidemiology of hip fractures among the elderly. Risk factors for fracture typeClin Orthop Rel Res1995311129135

- LevyARMayoNEGrimardGRates of transcervical and pertrochanteric hip fractures in the province of Quebec, Canada, 1981–1992Am J Epidemiol19951424284367625408

- CauleyJALuiLYGenantHKStudy of Osteoporotic Fractures Research and GroupRisk factors for severity and type of the hip fractureJ Bone Miner Res20092494395519113930

- FoxKMMagazinerJHebelJRKenzoraJEKashnerTMIntertrochanteric versus femoral neck hip fractures: differential characteristics, treatment and sequelaeJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci199954M635M64010647970

- KeeneGSParkerMPryorGAMortality and morbidity after hip fracturesBMJ1993307124812508166806

- MartinezAACuencaJPaniselloJJChanges in the morphology of hip fractures within a 10-year periodJ Bone Min Metab200119378381

- KaragasMRLu YaoGLBarrettJABeachMLBaronJAHeterogeneity of hip fracture: age, race, sex, and geographic patterns of femoral neck and trochanteric fractures among the US elderlyAm J Epidemiol19961436776828651229

- WilsonRTChaseGAChrischillesEAWallaceRBHip fracture risk among community-dwelling elderly people in the United States: a prospective study of physical, cognitive, and socioeconomic indicatorsAm J Public Health2006961210121816735617

- HolmbergAHJohnellONilssonPMNilssonJBerglundGAkessonKRisk fractures for hip fractures in a middle-aged population: a study of 33,000 men and womenOsteoporos Int2005162185219416177836

- CummingsSRMeltonLJEpidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fracturesLancet20023591761176712049882

- KoeckCMSchwappachDLNiemannFMIncidence and costs of osteoporosis-associated hip fractures in AustriaWien Klin Wochensch2001113371377

- LippunerKGolderMGreinerREpidemiology and direct medical costs of osteoporotic fractures in men and women in SwitzerlandOsteoporos Int200516Suppl 2S8S1715378232

- LeibsonCLTostesonANGabrielSERansomJEMeltonLJMortality, disability, and nursing home use for persons with and without hip fracture: a population-based studyJ Am Geriatr Soc2002501644165012366617

- HayesWCMyersERRobinovitchSNVan Den KroonenbergAEtiology and prevention of age-related hip fracturesBone19961877S86S8717551

- GehlbachSHAvruninJSPuleoETrends in hospital care for hip fracturesOsteoporos Int20071858559117146592

- AzharALimCKellyECost induced by hip fracturesIr Med J200810121321518807812

- CummingRGKlinebergRKatelarisACohort study of risk of institutionalisation after hip fractureAust N Z J Public Health1996205795829117962

- MeltonLJ3rdKearnsAEAtkinsonEJSecular trends in hip fracture incidence and recurrenceOsteoporos Int20092068769418797813

- DretakisKEDretakisEKPapakitsouEFPsarakisSSteriopoulosKPossible predisposing factors for the second hip fractureCalcif Tissue Int1998623663699504964

- DolkTInfluence of treatment factors on the outcome after hip fracturesUpsala J Med Sci1989942092212763393

- SchroderHMPetersenKKErlandsenMOccurrence and incidence of the second hip fractureClin Orthop Rel Res1993289166169

- YamanashiATamazakiKKanamoriMAssessment of risk factors for second hip fractures in Japanese elderlyOsteoporos Int2005161239124615729479

- IpDIpFKElderly patients with two episodes of fragility hip fractures form a special subgroupJ Orthop Surg (Hong Kong)20051424524817200523

- LönnroosEKautiaienHKarppiPHartikainenSKivirantaISulkavaRIncidence of second hip fractures. A population based studyOsteoporos Int2007181279128517440675

- BerrySDSamelsonEJHannanMTSecond hip fracture in older men and women: the Framingham studyArch Intern Med20071671971197617923597

- ThomasCDMayhewPMPowerJFemoral neck trabecular bone:loss with aging and role in preventing fractureJ Bone Miner Res2009241808181819419312

- KulmalaJSihvonenSKallinenMAlenMKivirantISipiläSBalance confidence and functional balance in relation to falls in older persons with hip fracture historyJ Geriatr Phys Ther20073011412018171495

- MyersAHYoungYLangloisJAPrevention of falls in the elderlyBone1996A1887S101S8717552

- GreenspanSLMyersERKielDPFall direction, bone mineral density, and function: risk factors for hip fracture in frail nursing home elderlyAm J Med19981045395459674716

- SabickMBHayJGGoelVKBanksSAActive responses decrease impact forces at the hip and shoulder in falls to the sideJ Biomechanic199932993998

- FormigaFLopez-SotoADuasoECharacteristics of fall-related hip fractures in community-dwelling elderly patients according to cognitive statusAging Clin Exp Res20082043443819039285

- LuukinenHKoskiKLaippalaPKivelaSFactors predicting fractures during falling impacts among home-dwelling older adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc199745130213099361654

- GrissoJAKelseyJLStromBLRisk factors for falls as a cause of hip fracture in women. The North East Study GroupN Engl J Med1991324132613312017229

- SlemendaCPrevention of hip fractures: risk factor modificationAm J Med199710365S73S9302898

- CouplandCWoodDCooperCPhysical inactivity is an independent risk factor for hip fracture in the elderlyJ Epidemiol Health199347441443

- WickhamCAWalshKCooperCDietary calcium, physical activity, and risk of hip fracture: a prospective studyBMJ198978898922510879

- CooperCBarkerDJPWickhamCPhysical activity, muscle strength, and calcium intake in fracture of the proximal femur in BritainBMJ1988297144314463147008

- CummingsSRNevittMCBrownerWSRisk factors for hip fractures in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research GroupN Engl J Med19953328148157862187

- LookerACMussolinoMESerum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and hip fracture risk in older US white adultsJ Bone Miner Res20082314315017907920

- SatoYInoseMHiguchiIHiguchiFKondoIChanges in the supporting muscles of the fractured hip in elderly womenBone20023032533011792605

- BeanNBennettKMLehmannABHabitus and hip fracture revisited: skeletal size, strength and cognition rather than thinness?Age Ageing1995244814848588536

- FarmerMEHarrisTMadansJHWallaceRBContoni-HuntleyJWhiteLRAnthropometric indicators and hip fracture. The NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up studyJ Am Geriatr Soc1989379162909610

- BirgeSJOsteoporosis and hip fractureClin Geriatr Med1993969868443741

- NielsonCMBouxseinMLFreitasSSEnsrudKEOrwollESOsteoporotic Fractures in Men Research GroupTrochanteric soft tissue thickness and hip fracture in older menJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200994249149619017753

- LordSRWardJAWilliamsPAnsteyKJPhysiological factors associated with falls in older community-dwelling womenJ Am Geriatr Soc199442111011177930338

- Dargent-MolinaPSchottAMHansDSeparate and combined value of bone mass and gait speed measurements in screening for hip fracture risk: results from the EPIDOS studyOsteoporos Int1999918819210367048

- GrissoJAKelseyJLO BrienLARisk factors for hip fracture in men. Hip fracture study groupAm J Epidemiol19971457867939143208

- HoidrupSSorensonTOStrogerULauritzenJBSchrollMGronbaekMLeisure-time physical activity levels and changes in relation to risk of hip fracture in men and womenAm J Epidemiol2001154606811427405

- SuriyawongpaisalPRajatanavinRTakkistienAWanvarieSApiyaawatPPhysical activity and risk factors for hip fracture in Thai menSoutheast Asian J Trop Med Public Health20013219620311485085

- CawthonPMFullmanRLMarshallLOsteoporotic fractures in men (MrOs) research groupJ Bone Miner Res2008231037104418302496

- JoakimsenRMMagnusJHFonneboVPhysical activity and predisposition for hip fractures: a reviewOsteoporos Int199775035139604045

- OwusaWWilletWAscherioASpiegelmanDRimmEFeskanichDBody anthropometry and the risk of hip and wrist fractures in men: results from a prospective studyObesity Res199861219

- LauEMSuriwongpaisalPLeeJKRisk factors for hip fracture in Asian men and women: the Asian osteoporosis studyJ Bone Min Res200116572580

- FarahmandBYMichaelsonKBaronJAPerssonPGLjunghallSBody size and fracture risk. Swedish Hip Fracture Study GroupEpidemiology20001121421911021622

- KanisJJohnellOGullbergBRisk factors for hip fracture in men from southern Europe: the MEDOS study. Mediterranean Osteoporosis StudyOsteoporos Int19999455410367029

- MussolinoMELookerACMadansJHLangloisJAOrwollESRisk factors for hip fracture in white men: The NHANES I Epidemiologic follow-up studyJ Bone Min Res199813918924

- LangloisJAVisserMDavidocLSMaggiSLiGHarrisTBHip fracture risk in older white men is associated with change in body weight from age 50 years to old ageArch Int Med19981589909969588432

- De LaetCKanisJAOdenABody mass as a predictor of fracture risk: a meta-analysisOsteoporos Int2005161330133815928804

- LangloisJAMussolinoMEVisserMLookerACHarrisTMadansJWeight loss from maximum body weight among middle-aged and older white women and the risk of hip fracture. The NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up studyOsteoporos Int20011276376811605743

- EnsrudKELipschutzRCCauleyJABody size and hip fracture risk in older women: a prospective studyAm J Med19971032742809382119

- GardnerTNSimpsonAHRWBoothCMeasurement of impact force, simulation of fall and hip fractureMed Eng Phys19982057659664286

- ParkerEDPereiraMAVirnigBFolsomARThe association of hip circumference with incident hip fracture in a cohort of postmenopausal women: the Iowa Women’s Health StudyAnn Epidemiol20081883684118940632

- CummingRGKlinebergRJFall frequency and risk of hip fracturesJ Am Geriatr Soc1994427747788014355

- MaffulliNDougallTWBrownMTFGoldenMHNNutritional differences in patients with proximal femoral fracturesAge Ageing19992845846210529040

- DretakisKEChristadoulouNASignificance of endogenic factors in the location of fractures of the proximal femurActa Orthop Scand1983541982036845994

- SkalbaPKorfantyAMroczkaWWojtowiczMChanges of SHBG concentrations in postmenopausal womenGinekol Pol2001721388139211883284

- AbrahamsenBNielsenMFEskildsenPAndersenJTWalterSBrizenKFracture risk in Danish men with prostate cancer: a nationwide register studyBJU Int200710074975417822455

- WeiTSHuCHWangSHHwangKLFall characteristics, functional mobility and bone mineral density as risk factors of hip fracture in the community-dwelling ambulatory elderlyOsteoporos Int2001121050105511846332

- JohnellOKanisJAOdenAPredictive value of BMD for hip and other fracturesJ Bone Mineral Res20052011851194

- FoxKMCummingsSRWilliamsEStoneKFemoral neck and intertrochanteric fractures have different risk factors: a prospective studyOsteoporos Int2000111018102311256892

- FitzpatrickPKirkePNDalyLVan RooijIDinnEBurkeHPredictors of first hip fracture and mortality in older womenIrish J Med Sci2001170495311440414

- CummingsSRKelseyJLNevittMCO’DowdKJEpidemiology of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracturesEpidemiol Rev198571782083902494

- CummingsSRNevittMCA hypothesis: the causes of hip fracturesJ Gerontol198944M108M111

- ArdenNKGriffithsGOHartDJDoyleDVSpectorTDThe association between osteoarthritis and osteoporotic fracture: the Chingford studyBr J Rheumatol199635129913049010060

- BoonenSDequekerJPelemansWRisk factors for falls as a cause of hip fracture in the elderlyActa Clin Belg1993481901948396300

- JohnellOMeltonLJIIIAtkinsonEJO FallonWMKurlandLTFracture risk in patients with parkinsonism: a population-based study in Olmsted County, MinnesotaAge Ageing19922132381553857

- NevittMCCummingsSRKiddSBlackDRisk factors for recurrent nonsyncopal fallsJAMA1989261266326682709546

- BuchnerDMLarsonEBFalls and fractures in patients with Alzheimer-type dementiaJAMA1987257149214953820464

- ChristodoulouNADretakisEKSignificance of muscular disturbances in the localization of fractures of the proximal femurClin Orthop Rel Res1984187215217

- SchwartzAVSellmeyerDEEnsrudKEOlder women with diabetes have an increased risk of fracture: a prospective studyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200186323811231974

- BoonenSBroosPHaentjensPFactors associated with hip fracture occurrence in old age. Implications in the postsurgical managementActa Chir Belg19999918518910499393

- PoorGAtkinsonEJO FallenWMMeltonLJIIIPredictors of hip fractures in menJ Bone Min Res19951019001907

- GrissoJAKelseyJLStromBLRisk factors for hip fracture in black women. The Northeast Hip Fracture GroupN Engl J Med1994330155515598177244

- FrenchDDBassEBradhamDDCampbellRRRubensteinLZRehospitalization after hip fracture: predictors and prognosis from a national veterans studyJ Am Geriatr Soc20085670571018005354

- RocheJJWWennRTSahotoOMoranCGEffect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohortBMJ2005331137416299013

- GuoZWillsPViitanenMFastbomJWinbladBCognitive impairment, drug use, and the risk of hip fracture in persons over 75 years old: a community-based prospective studyAm J Epidemiol19981488878929801019

- HasegawaYSuzukiSWingstrandHRisk of mortality following hip fracture in JapanJ Orthop Sci20071211311717393264

- GreenspanSLMyersERMaitlandLAResnickNMHayesWCFall severity and bone mineral density as risk factors for hip fracture in ambulatory elderlyJAMA19942711281338264067

- MagazinerJSimonsickEMKashnerTMHebelJRKenzoraJEPredictors of functional recovery one year following hospital discharge for hip fracture: a prospective studyJ Gerontol199045M101M1072335719

- ClemensonLCummingRGRolandMCase-control study of hazards in the home and risk of falls and hip fracturesAge Ageing199625971018670535

- HuangZHimesJHMcGovernPGNutrition and subsequent fracture risk among a national cohort of white womenAm J Epidemiol19961441241348678043

- IversRQCummingRGMitchellPSimpsonJMPedutoAJVisual risk factors for hip fracture in older peopleJ Am Geriatr Soc20035135636312588579

- IversRQNortonRCummingRGButlerMCampbellAJVisual impairment and risk of hip fractureAm J Epidemiol200015263363911032158

- PfisterAKMcJunkinJSantrockDAHip fracture outcomes and their prevention in Kanawha County, West VirginiaWest Virginia Med J199995170174

- LichtensteinMJGriffenMRCornellJEMalcolmERayWARisk factors for hip fractures occurring in the hospitalAm J Epidemiol20001408308387977293

- FelsonDTAndersonJJHannanMTMiltonRCWilsonPWKielDPImpaired vision and hip fracture. The Framingham StudyJ Am Geriatr Soc1989374955002715555

- RashiqSLoganRFARole of drugs in fractures of the femoral neckBMJ19862928618633083912

- LiuBAndersonGMittmannNUse of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants and risk of hip fractures in elderly peopleLancet1998351130313079643791

- ReesLHBesserGMJeffcoateWJGoldieDJMarksVAlcohol induced pseudo-Cushing’s syndromeLancet1977172672866521

- HemenwayDColditzGAWillettWCStampferMJSpeizerFEFractures and lifestyle: effect of cigarette smoking, alcohol intake and relative weight on the risk of hip and forearm fractures in middle-aged womenAm J Public Health198878155415583189632

- PacherPUngvariZSelective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor antidepressants increase the risk of falls and hip fractures in elderly people by inhibiting cardiovascular ion channelsMed Hypotheses20015746947111601871

- SheppardMCHolderRFranklynJALevothyroxine treatment and occurrence of fracture of the hipArch Int Med200216233834311822927

- Jacqmin-GaddaHFourrierACommengesDDartiguesJFRisk for fractures in the elderlyEpidemiology199894174239647906

- BoltonJMMetgeCLixLPriorHSareenJLeslieWDFracture risk from psychotropic medications: a population-based analysisJ Clin Psychopharmacol20082838439118626264

- NortonRCampbellJLeeJTRobinsonEButlerMCircumstances of falls resulting in hip fractures among older peopleJ Am Geriatr Soc199745110811129288020

- KingMBTinettiMEA multifactorial approach to reducing injurious fallsClin Geriatr Med1996127457598890114

- AllanderEGullbergBJohnellOKanisJARanstamJElfforsLCircumstances around the fall in a multinational hip fracture risk study: a diverse pattern for preventionAccid Anal Prev1998306076169678214

- LloydBDWilliamsonDASinghNARecurrent and injurious falls in the year following hip fracture: a prospective study of incidence and risk factors from the Sarcopenia and Hip Fracture studyJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci20096459960919264957

- FisherAADavisMWRubenachSEThe site specific epidemiology of the hip fracture in the Australian Capital Territory with projections for the first half of the 21st century: implications for clinical management and health services planningAustralasian J Aging2007264551

- AhmedLASchirmeHBjorneremAThe gender- and age-specific 10-year and lifetime absolute fracture risk in Tromse, NorwayEur J Epidemiol20092444144819484362

- HiebertRAharonoffGBCaplaELEdolKAZuckermanJDKovalJJTemporal and geographic variation in hip fracture rates for people aged 65 or older, New York State, 1985–1996Am J Orthop20053425225515954693

- Auron-GomezMMichotaFMedical management of hip fractureClin Geriatr Med20082470171918984382

- AbrahamsenBvan StaaTArielyROlsonMCooperCExcess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological reviewOsteoporos Int2009201633165019421703

- EklundFNordstromANeoviusMVariation in fracture rates by country may not be explained by differences in bone massCalcif Tissue Int200985101619533011

- ChangKPCenterJRNguyenTVEismanJAIncidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures in elderly men and women: Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology StudyJ Bone Miner Res20041953253615005838

- BoyceWJVesseyMPRising incidence of fracture of the proximal femurLancet198511501512857223

- JohalKSBoultonCMoranCGHip fractures after falls in hospital: a retrospective observational cohort studyInjury20094020120419100542

- Van HeldenSVan GeelACGeusensPPBone and fall-related fracture risks in women and men with a recent clinical fractureJ Bone Joint Surg20089024124818245581

- GrueEVKirkevoldMRanhoffAHPrevalence of vision, hearing, and combined vision and hearing impairments in patients with hip fractureJ Clin Nurs2009183037304919732248

- PiirtolaMVahlbergTLopponenMRaihaIIsoahoRKivelaSLFractures as predictors of excess mortality in the aged-a population-based study with a 12-year follow-upEur J Epidemiol20082374775518830674

- RappKBeckerCLambSEIcksAKlenkJHip fractures in institutionalized elderly people: incidence rates and excess mortalityJ Bone Miner Res2008231825183118665785

- MoayyeriASoltaniALarijaniBEpidemiology of hip fracture in Iran: results from the Iranian Multicenter Study on Accidental InjuriesOsteoporos Int2006171252125716680499

- DavidsonCWMerrileesMJWilkinsonTJMcKieJSGilchristNLHip fracture mortality and morbidity – can we do better?N Z Med J200111432933211548098

- MyersAHRobinsonEGVan NattaMLMichelsonJDCollinsKBakerSPHip fractures among the elderly: factors associated with in-hospital mortalityAm J Epidemiol1991134112811371746523

- StavrouZPErginousakisDALoizidesAATzevelekosSAPapagiannakosKPMortality and rehabilitation following hip fractureActa Orthop Scand1997275Suppl8991

- CooperCThe crippling consequences of fractures and their impact on quality of lifeAm J Med1997103Part A:12S19S9302893

- de LuiseCBrimacombeMPedersonLSorensonHTComorbidity and mortality following hip fracture: a population-based cohort studyAging Clin Exp Res20082041241819039282

- KarlssonMNilssonJSernboIRedlund-JohnellIJohnellOObrantKJChanges of bone mineral mass and soft tissue composition after hip fractureBone19961819228717532

- ParkerMJPalmerCRPrediction of rehabilitation after hip fractureAge Ageing19952496987793343

- MyersAHPalmerMHEngelBTWarrenfeltzDJParkerJAMobility in older patients with hip fractures: examining prefracture status, complications, and outcomes at discharge from the acute-care hospitalJ Orthop Trauma1996b10991078932668

- FormigoFNavarroMDuasoEFactors associated with hip fracture-related falls among patients with a history of recurrent fallingBone20084394194418656561

- BaranganJDFactors that influence recovery from hip fracture during hospitalizationOrthop Nurs1990919292216535

- CederLSvenssonKThorngrenKStatistical prediction of rehabilitation in elderly patients with hip fracturesClin Orthop Rel Res1980152185190

- FoxKMHawkesWGHebelJRMobility after hip fracture predicts health outcomesJ Am Geriatr Soc1988461691739475444

- RungeMSchactEProximal femoral fractures in the elderly: pathogenesis, sequelae, interventionsRehabil (Stuttg)199938160169

- AngthongCSuntharapaTHarnroongrojTMajor risk factors for the second contralateral hip fracture in the elderlyActa Orthop Traumatol Turc20094319319819717935

- StoleePPossJCookRJByrneKHirdesJPRisk factors for hip fracture in older home care clientsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci20096440341019196903

- KanisJAJohanssonHOdenAAssessment of fracture riskEur J Radiol2009[Epub ahead of print].

- ChenJSSambrookPNSimpsonJMRisk factors for hip fracture among institutionalised older peopleAge Ageing20093842943419406974

- KarlssonMKNordqvistAKarlssonCPhysical activity, muscle function, falls and fracturesFood Nutr Res200852DOI: 10.3402/fnr.v52i0.1920

- TrimpouPLandin-WilhelmsenKOdénARosengrenAWilhelmsenLMale risk factors for hip fracture-a 30-year follow-up study in 7,495 menOsteoporos Int2009528[Epub ahead of print].

- RygJRejnmarkLOvergaardSBrixenKVestergaardPHip fracture patients at risk of second hip fracture-a nationwide population-based cohort study of 169,145 cases during 1977–2001J Bone Miner Res2009241299130719257816

- ShaoCJHsiehYHTsaiCHLaiKAA nationwide seven-year trend of hip fractures in the elderly poplation of TaiwanBone20094412512918848656

- DornerTWeichselbaumELawrenceKViktoria SteinKRiederAAustrian osteoporosis report: epidemiology, lifestyle factors, public health strategiesWien Med Wochenschr200915922122919484204

- TanrioverMDOzSGTanrioverAHip fractures in a developing country: osteoporosis frequency, predisposing factors and treatment costsArch Gerontol Geriatr2009527[Epub ahead of print].

- BassEFrenchDDBradhamDDA national perspective of Medicare expenditures for elderly veterans with hip fracturesJ Am Med Dir Assoc2008911411918261704

- LawrenceTMWhiteCTWennRMoranCGThe current hospital costs of treating hip fracturesInjury200536889115589923

- TrompAMOomsMEPoo-SnijdersCRoosJCLipsPPredictors of fractures in elderly womenOsteoporos Int20001113414010793871

- MargolisKLEnsrudKESchreinerPJTaborHKBody size and risk for clinical fractures in older women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research GroupAnn Intern Med200013312312710896638

- CummingsSRNevittMCNon-skeletal determinants of fractures: The potential importance of the mechanism of falls. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research GroupOsteoporos Int19944Suppl 167708081063

- WolinskyFDFitzgeraldJFThe risk of hip fracture among noninstitutionalized older adultsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci199449S165S175

- JonesGNguyenTSambrookPNLordSRKellyPJEismanJAOsteoarthritis, bone density, postural stability, and osteoporotic fractures: a population based studyJ Rheumatol1995229219258587083

- ParkerMJTwemlowTRPryorGA.Environmental hazards and hip fracturesAge Ageing1996253223258831880

- ChenZMaricicMAragakiAKFracture risk increases after the diagnosis of breast or other cancers in postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health InitiativeOsteoporosis Int200920527536

- TafuriSMartinelliDBalducciMTFortunatoFPratoRGerminarioCEpidemiology of femoral neck fractures in Puglia (Italy): an analysis of existing dataIg Sanita Pubbl20086462363619188938

- CollinsTCEwingSKDiemSJfor the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study GroupPeripheral arterial disease is associated with higher rates of hip bone loss and increased fracture risk in older menCirculation20091192305231219380619

- WolinskyFDBentlerSELiuLObrizanMCookEAWrightKBRecent hospitalization and the risk of hip fracture among older AmericansJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci20096424925519196641

- SahniSHannanMTGagnonDProtective effect of total and supplemental vitamin C intake on risk of hip fracture-a 17-year follow-up from the Framingham Osteoporosis StudyOsteoporos Int2009201853186119347239

- KristensenMTBandholmTBenckeJEkdahlCKehletHKnee-extension strength, postural control and function are related to fracture type and thigh edema in patients with hip fractureClin Biomech200924218224

- HaginoHKatagariHOkanoTYamamotoKTeshimaRIncreasing incidence of hip fracture in Tottori Prefecture, Japan: trend from 1986–2001Osteoporos Int2005161963196816133645

- HernandezJLOlmosJMAlonsoMATrends in hip fracture epidemiology over a 14-year period in a Spanish populationOsteoporos Int20061746447016283063

- GiversenIMTime trends of age-adjusted incidence rates of first hip fractures: a register-based study among older people in Viborg County, Denmark, 1987–1997Osteoporos Int20061755256416408148

- LönnroosEKautiainenHKarppiPHuuskoTHartikainenSKivirantaIIncreased incidence of hip fractures. A population based-study in FinlandBone20063962362716603427

- IcksAHaastertBWildnerMBeckerCMeyerGTrend of hip fracture incidence in Germany 1995–2004: a population-based studyOsteoporos Int2008191139114518087659

- HoltGSmithRDuncanKHutchisonJDReidDChanges in population demographics and the future incidence of hip fractureInjury20094072272619426972

- DoddsMKCoddMBLooneyAMulhallKJIncidence of hip fracture in the Republic of Ireland and future projections: a population-based studyOsteoporos Int200941[Epub ahead of print].

- JetteAMHarrisBClearyPDCampionEWFunctional recovery after hip fractureArch Phys Med Rehabil1987687357403662784

- BonarSKTinettiMESpeechleyMCooneyLMFactors associated with short-versus long term skilled nursing facility placement among community-living hip fracture patientsJ Am Geriatr Soc199038113911442172352

- JalovaaraPVirkkunenHQuality of life after primary hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture. Six year follow-up of 185 patientsActa Orthop Scand1991622082172042461

- MarottoliRABerkmanLFCooneyLMJrDecline in physical function following hip fractureJ Am Geriatr Soc1992408618661512379

- AharonoffGBKovalKJSkovronMLZuckermanJDHip fractures in the elderly: predictors of one year mortalityJ Orthop Trauma1997111621659181497

- WolinskyFDFitzgeraldJFStumpTEThe effect of hip fracture on mortality, hospitalization, and functional status: a prospective studyAm J Public Health1997873984039096540

- KoikeYImaizumiHTakahashiEMatsubaraYKomatsuHDetermining factors of mortality in the elderly with hip fracturesTohoku J Exp Med199918813914210526875

- GiaquintoSMajolaIIPalmaERoncacciSSciarraAVittoriaEVery old people can have a favorable outcome after hip fracture: 58 patients referred to rehabilitationArch Gerontol Geriatr20001131810989159

- MaggioDUbaldiESimonelliGCenciSPedoneCCherubiniAHip fracture in nursing homes: an Italian study on prevalence, latency, risk factors, and impact on mobilityCalc Tissue Int200168337341

- Van BalenRSteyerbergEWPolderJJRibbersTLHabbemaJDCoolsHJHip fracture in elderly patients: outcomes for function, quality of life, and type of residenceClin Orthop Rel Res2001390232243

- KirkePNSuttonMBurkeHDalyLOutcome of hip fracture in older Irish women: a 2 year follow-up of subjects in a case-control studyInjury2002165415

- LeboffMSNarweckerRLaCroixAHomocysteine levels and risk of hip fracture in postmenopausal womenJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2009941207121319174498

- ClintonJFrantaAPolissarNLProximal humeral fracture as a risk factor for subsequent hip fracturesJ Bone Joint Surg Am20099150351119255209