Abstract

In order to improve health care efficiency and effectiveness, treatments should provide disease improvement or resolution at a reasonable cost. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) published a guideline for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) in 2009 based on review of the literature up to April 6, 2007. We have now reviewed the material published since then. Through reviewing evidence-based articles published during this period, this paper examines the current options and trends for treating CTS. We performed a systematic review of the randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and practice guidelines to present the outcomes of current treatments for this disease. Twenty-five studies met our inclusion criteria. Thirteen randomized, controlled trials and 12 systematic reviews, including three Cochrane database systematic reviews, were retrieved. Our review revealed that most of the recent studies support the AAOS guideline. However, the recent literature demonstrates a trend towards recommending early surgery for CTS cases with or without median nerve denervation, although the AAOS guideline recommends early surgical treatment only for cases with denervation. The usefulness of splinting and steroids as initial treatments for improving patients’ symptoms are also supported by the recent literature, but these effects are temporary. The evidence level for ultrasound treatment is still low, and further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of this treatment. Finally, our review revealed a paucity of articles comparing the costs of CTS diagnosis and treatment. With the recent focus on health care reform and rising costs, attention to the direct and indirect costs of health care is important for all conditions. Future well designed studies should include cost analyses to help determine the cost burden of CTS.

Introduction

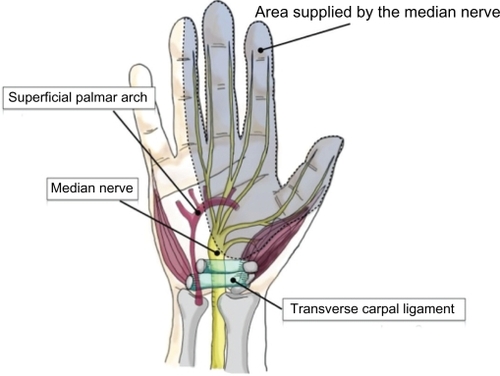

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), or median neuropathy, is a pathologic condition in which the median nerve is compressed at the wrist, leading to pain, paresthesia, numbness, and weakness in the median nerve distribution of the hand (). CTS is a common peripheral nerve entrapment syndrome that has received a lot of attention because of its association with work-related disability.Citation1–Citation3

Epidemiology

CTS is one of the most common hand disorders and entrapment neuropathies. The highest incidence is among middle-aged and elderly women.Citation4,Citation5 The CTS incidence rate in the US has been estimated at 1–3 per 1000 persons per year.Citation6 The prevalence is approximately 50 cases per 1000 subjects in the general population.Citation6,Citation7 The large prevalence of CTS is an important issue in the workplace because it is directly related to waning productivity resulting from work disabilityCitation1–Citation3 and is associated with high-cost treatment.Citation8 According to a 2008 report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, CTS is associated with the second longest average time away from work (28 days) out of the major disabling diseases and illnesses in all private industries.Citation9 Also, according to the National Institutes of Health, the average lifetime cost of CTS, including medical bills and loss time from work, is approximately $30,000 for each affected worker.Citation10 As a result, choosing the proper treatment for CTS is crucial in improving patient quality of life and containing medical costs to a reasonable level.

Objectives

The aim of this article is to provide an evidence-based review of the most current treatment options and trends for CTS, including both conservative and surgical treatments.

In 2008, a systematic review and practice guideline entitled “Clinical Practice Guideline on the Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome” was undertaken by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), the summary of which was published in 2009.Citation11 This guideline consists of nine specific recommendations and is useful for evidence-based clinical practice. The literature search undertaken in creating this guideline included articles from 1966 through April 6, 2007. Almost three years have passed since this search and many new articles with high evidence-based analysis have been published. For clinicians to adhere to the most current evidence-based recommendations, it is important that we update the literature on treatment options and outcomes on a routine basis. In order to improve health care efficiency and effectiveness, treatments should provide disease improvement or resolution at a reasonable cost. For common conditions like CTS, preferentially allocating resources to a more effective treatment may have a large impact on reducing the overall national costs of treatment. Furthermore, the practice of patient-centered care by considering patients’ needs and activity levels are essential considerations in disease management.

Material and methods

Literature identification

The aim of our review is to provide optimal treatment recommendations based on the evidence available in the literature. We conducted a literature search using MedLine and the Cochrane Library to identify all citations of original research studies related to treatment in CTS. Details of the search strategy are given in .

Table 1 Search strategy

Selection of studies

Based on title and abstract, two reviewers independently selected the trials to be included in this review. All articles selected by at least one of the reviewers were retrieved for examination. Articles fulfilling all the following inclusion criteria were included in the final review: (1) type of article (meta-analysis, practice guideline, randomized controlled trial or systematic review), (2) publication in English language, (3) published between April 7, 2007 and May 28, 2010, (4) study sample consisting of patients with clinically and/or electrophysiologically confirmed CTS, and (5) evaluation of the efficacy of one or more treatment options. Reference lists of all relevant studies from the electronic search were manually searched to identify additional eligible studies.

Quality assessment

We considered the quality of the available evidence. Quality was determined using a “levels of evidence” approach, comprising five levels (). The higher the level of evidence, the greater the ability to draw causal inferences from the results of a study and, hence, the greater the quality of that study. This quality assessment is the same as that used for formulation of the AAOS Guideline on the Treatment of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, available from http://www.aaos.org/Research/Committee/Evidence/loetable1.pdf.

Table 2 Levels of evidence for therapeutic studies investigating the results of treatment

Data extraction and synthesis

The selected studies were gathered on the basis of kind of intervention, ie, surgical procedure, nonsurgical procedure, and postoperative treatment. The following data were extracted independently by two reviewers: characteristics of study design, population (size, age, gender, and duration of disease), intervention (details about surgical procedure), length of follow-up, outcome evaluation, and overall clinical results. Conclusions of our search were compared with existing evidence or added as new knowledge. We discussed differences in recommendations based on outcomes and cost-effectiveness based on the evidence in the CTS literature and the AAOS guidelines.

Results and discussion

Twenty-five studies met our inclusion criteria. Thirteen randomized controlled trials and 12 systematic reviews, including three Cochrane database systematic reviews, were retrieved.

Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment

Optimal treatment of CTS should be patient-oriented to provide patients with relief of symptoms, and as noninvasively, permanently, and inexpensively as possible. The treatment options for CTS are divided into two major groups, ie, nonsurgical and surgical. In 1993, the American Academy of Neurology’s official practice guidelines recommended treating CTS with noninvasive options first and considering surgery only if noninvasive treatment proved ineffective.Citation12 In recent years, however, initial surgical management has gained support, due to more accurate diagnostic techniques and the increased number of trained hand surgeons in the community.Citation13 However, there is still controversy over whether surgical or nonsurgical treatment should be chosen as the initial treatment of CTS.

The AAOS guideline for the treatment of CTSCitation14,Citation15 recommends both nonsurgical and surgical treatments for early CTS without denervation of the median nerve, although they also recommend an initial course of nonoperative treatment. Surgery can then be considered if there is clinical evidence of median nerve denervation or if the patient would prefer surgery over conservative management.Citation14 In fact, the recent literature demonstrates a trend towards recommending early surgery with or without median nerve denervation.Citation13 In 2009, a study of 116 patients with CTS compared the treatment outcomes between an experimental group of 57 patients who received surgical management and a control group of 59 patients who received a nonsurgical treatment regimen of hand therapy and ultrasound. The results showed that the surgical group achieved modestly better outcomes in terms of hand function and symptoms at both three months and one year when compared with the control group (Level I).Citation13 Another meta-analysis concluded that surgical treatment relieves symptoms better than splinting, but the evidence for surgical treatment being superior to steroid injections is unclear (Level I).Citation16 Therefore, more research is needed to determine the best treatment for patients with mild to moderate symptoms, as well as to identify which patients should forego conservative management and undergo surgery as the initial treatment.

Moreover, several economic analyses suggest that surgery should be considered as the initial form of treatment when the diagnosis of CTS is confirmed by nerve conduction studies, because the surgical treatment option has the most favorable cost-utility ratio.Citation17,Citation18

Nonsurgical treatments

Only three conservative treatments are supported by a substantial body of experimental evidence: splinting, steroids, and ultrasound.Citation19 The AAOS recommends that when initial conservative treatment fails to resolve a patient’s symptoms within 2–7 weeks, physicians should move on to another nonoperative treatment or surgery.

Splinting

For patients with mild CTS symptoms, the simplest treatment is a night splint. Splinting has the advantage of being inexpensive and is associated with a minimal complication rate. The immobilization may decrease the pressure around the soft tissue in the carpal tunnel, which enhances blood circulation and relieves pressure on the median nerve. For this reason, splinting provides many patients with relief from the numbness and tingling sensation experienced at night or during extended periods of rest. For some patients, wearing a splint may also be necessary during the day. The AAOS recommends that splinting be considered before surgery when treating CTS. Recent evidence-based studies (Level II)Citation19,Citation20 also support this suggestion. Specifically, research suggests that a splint that maintains the wrist in the neutral position may be more effective than a wrist cock-up splint (Level II).Citation21 We can conclude that splinting for CTS is useful for relief of some symptoms in the early stages of CTS, and has the benefits of being cost-effective and without serious adverse effects. It should be considered as an initial treatment option before considering surgery, especially in mild or moderate cases.

Steroids

The AAOS recommends local steroid injection when treating CTS before surgery is considered, and oral steroids as a secondary option. Their report also concluded that steroids are more effective than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and diuretics, but also have the potential for more serious side effects. This conclusion is supported by a recent study by Marshall et al who concluded that local steroid injections are more effective than oral steroids for up to three months (Level II).Citation22 On the other hand, another recent study indicated that local steroid injection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with concomitant use of wrist splints might offer patients with CTS variable and effective treatment options for the management of functional scores and nerve conduction parameters (Level II).Citation23 Moreover, a further study revealed that corticosteroid iontophoresis was not effective in the treatment of mild to moderate CTS (Level II).

As a result, steroid treatment for CTS, particularly local injection, is effective for temporary relief of symptoms in many patients. However, the efficacy and duration of symptom relief with the steroid injections are still unknown. Further investigation is needed to determine the long-term outcomes of local steroid injection and how many times and how frequently the steroid injections should be repeated.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound treatment consists of directing high-frequency sound waves at the inflamed area. The sound waves are converted into heat in the deep tissues of the hand, and are presumed to open the blood vessels, allowing oxygen to be delivered to the injured tissue. As a result, it is suggested that ultrasound therapy may accelerate the healing process in damaged tissues.Citation24 It is often prescribed along with nerve and tendon exercises. The AAOS guideline recommends ultrasound treatment of CTS. However, this recommendation was based on the results of only two studies, hence the low evidence level of this recommendation.Citation24,Citation25 To increase the evidence level of ultrasound treatment for CTS, we need further studies comparing an ultrasound group against a placebo group. There was no updated information in this regard.

Surgical treatments

Carpal tunnel release (CTR) is the most common hand and wrist surgery performed in the US, with an estimated 400,000 operations performed per year.Citation26 CTR as an effective treatment for CTS is supported by high quality evidence.Citation14 There are several variations of CTR surgery. The two major types are open carpal tunnel release (OCTR) and endoscopic carpal tunnel release (ECTR). OCTR can be further classified into full-open and mini-open with a one inch incision. Regardless of selection of these treatment options, the most important thing is complete division of the flexor retinaculum.Citation14

Open carpal tunnel release

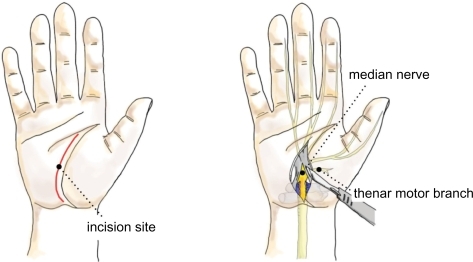

Traditionally, OCTR was done through a relatively large 4–5 cm longitudinal incision extending from Kaplan’s cardinal line distally to beyond the wrist crease proximally (). Over time, the size of this incision has gradually decreased, and most hand surgeons today perform primary OCTR through a 2–4 cm incision, which ends approximately 2 cm distal to the wrist crease. OCTR has been shown to be an effective and relatively safe procedure, and is established as the standard surgical treatment for CTS.Citation27,Citation28 It has produced uniformly excellent results, with high patient satisfaction and a low complication rate.Citation29,Citation30 The outcome of this procedure can be complicated by scar tenderness, grip and pinch weakness, and pillar pain, which are all related to the incision.

There are two recent publications concerning OCTR. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews concluded that there was no strong evidence supporting the need for replacement of standard OCTR by alternative surgical procedures for the treatment of CTR (Level I).Citation31 In contrast, the other study compared conventional OCTR with the double-incision technique and showed that the limited open technique using the double incision was advantageous compared with the standard technique in tackling scar-related morbidities in terms of decreasing pillar pain and scar sensitivity (Level II).Citation32

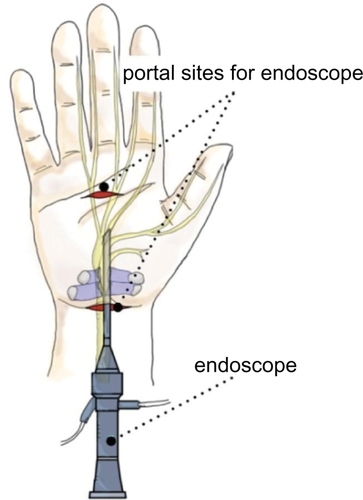

Endoscopic carpal tunnel release

ECTR refers to a method of performing CTR using an endoscope or arthroscopic deviceCitation33 (). This entails a less invasive procedure than standard OCTR. ECTR was invented to address the potential complications of OCTR by using smaller incisions placed away from the middle of the palm.Citation34,Citation35 It is assumed that preservation of the superficial fascia and adipose tissue over the flexor retinaculum allows faster recovery of grip strength, less scar tenderness and pillar pain, and earlier return to work.Citation35,Citation36 According to the AAOS guideline,Citation14 endoscopic release offers better outcomes than OTCR at 12 weeks after surgery in terms of pain relief, time until return to work, and wound-related complications. In recent studies comparing OCTR and two-portal ECTR, Atroshi et alCitation37 reported that the outcomes were equivalent, other than ECTR offering a shorter recovery period. However, critics of ECTR report higher complication ratesCitation38–Citation40 due to the technical difficulty of the procedure, as well as greater cost when compared with OCTR.Citation35,Citation41 However, experienced surgeons can successfully complete the operation without too many complications.Citation42 Therefore, the decision to perform ECTR is influenced by the surgeon’s experience and patient factors, including occupation, socioeconomic status, and preference. This evidence is also supported by the recent Cochrane database systematic review. They concluded that the decision to perform ECTR instead of OCTR seems to be guided by the surgeon’s and patient’s preferences (Level I).Citation31

Mini-open carpal tunnel releaseCitation43,Citation44

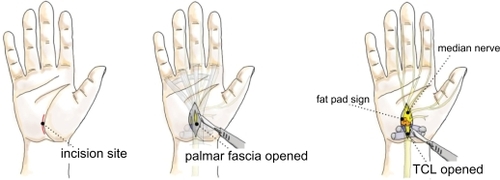

In recent years, many surgeons have adopted the “mini” OCTR, also called the short-incision procedure. The idea behind the “mini” procedure is to combine the simplicity and safety of OCTR with the reduced tissue trauma and postoperative morbidity of ECTR by using a short-incision, open technique. The incision begins just distal to the distal wrist crease and extends no further than Kaplan’s cardinal line, which extends along the distal border of the outstretched thumb obliquely toward the pisiform ().

According to the AAOS guideline, when minimal incision release was compared with open release in Level I studies, minimal incision release offered superior outcomes in terms of symptom relief, functional status, and scar tenderness. When compared with endoscopic release, minimal incision was favored when pain at two or four weeks was the outcome measure.Citation14,Citation42 On the other hand, Cellocco et alCitation45 prospectively compared the safety and effectiveness of mini-incision (less than 2 cm), and a limited open technique (3–4 cm) for CTR in 185 consecutive patients, with a five-year minimum follow-up. Patient status was evaluated with a modified version of the Boston Carpal Tunnel questionnaire, administered preoperatively and at 19, 30, and 60 months postoperatively. Mini-incision CTR had superior outcomes over the standard technique in terms of recovery time, pillar pain, and recurrence rate (Level II).

Conclusion

In order to improve health care efficiency and effectiveness, treatments should provide disease improvement or resolution at reasonable cost. Furthermore, we should always think about patient-centered care in determining the best treatment for each patient’s condition. When considering the treatment options for CTS, only four treatments are supported by some evidence: splinting, steroids, ultrasound, and surgery. Splinting and steroids are useful as initial treatment for improving symptoms, but their effects are temporary. The evidence level for ultrasound treatment is poor and further investigations are needed. Moreover, early treatment using mini-OCTR appears to be the preferred treatment approach.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- KatzJNLewRABessetteLPrevalence and predictors of longterm work disability due to carpal tunnel syndromeAm J Ind Med19983365435509582945

- FeuersteinMMillerVLBurrellLMBergerROccupational upper extremity disorders in the federal workforce. Prevalence, health care expenditures, and patterns of work disabilityJ Occup Environ Med19984065465559636935

- LatinovicRGullifordMCHughesRAIncidence of common compressive neuropathies in primary careJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200677226326516421136

- BeckerJNoraDBGomesIAn evaluation of gender, obesity, age and diabetes mellitus as risk factors for carpal tunnel syndromeClin Neurophysiol200211391429143412169324

- GeogheganJMClarkDIBainbridgeLCSmithCHubbardRRisk factors in carpal tunnel syndromeJ Hand Surg Br200429431532015234492

- AshworthNCarpal Tunnel SyndromeAvailable from: http://www.emedicine.com/pmr/topic21.htm Accessed on May 28, 2010.

- FullerDCarpal Tunnel SyndromeAvailable from: http://www.emedicine.com/orthoped/topic455.htm Accessed on 28 May, 2010.

- HanrahanLPHigginsDAndersonHSmithMWisconsin occupational carpal tunnel syndrome surveillance: The incidence of surgically treated casesWis Med J199392126856898109131

- US Department of Labor Bureau of Labor StatisticsAvailable from: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/osh2.t11.htm Accessed on Jun 23, 2010.

- National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS)Available from: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/carpal_tunnel/detail_carpal_tunnel.htm Accessed on Jun 24, 2010.

- KeithMWMasearVChungKCAmerican Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline on diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndromeJ Bone Joint Surg Am200991102478247919797585

- Practice parameter for carpal tunnel syndrome (summary statement). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology19934311240624098232968

- JarvikJGComstockBAKliotMSurgery versus non-surgical therapy for carpal tunnel syndrome: A randomised parallel-group trialLancet200937496951074108119782873

- KeithMWMasearVAmadioPCTreatment of carpal tunnel syndromeJ Am Acad Orthop Surg200917639740519474449

- American Academy of OrthopaedicSurgeons Work Group PanelClinical practice guideline on the treatment of carpal tunnel syndromeAvailable at: www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/CTStreatmentguide.asp Accessed on Jun 24, 2010.

- VerdugoRJSalinasRACastilloJLCeaJGSurgical versus non-surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndromeCochrane Database Syst Rev20084CD00155218843618

- PomeranceJZurakowskiDFineIThe cost-effectiveness of nonsurgical versus surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndromeJ Hand Surg Am20093471193120019700068

- HaaseSCChungKCThe cost-effectiveness of nonsurgical versus surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome: Invited commentaryJ Hand Surg Am20093471201120319700069

- PiazziniDBAprileIFerraraPEA systematic review of conservative treatment of carpal tunnel syndromeClin Rehabil200721429931417613571

- de AngelisMVPierfeliceFDi GiovanniPStanisciaTUnciniAEfficacy of a soft hand brace and a wrist splint for carpal tunnel syndrome: A randomized controlled studyActa Neurol Scand20091191687418638040

- BriningerTLRogersJCHolmMBBakerNALiZMGoitzRJEfficacy of a fabricated customized splint and tendon and nerve gliding exercises for the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome: A randomized controlled trialArch Phys Med Rehabil200788111429143517964883

- MarshallSTardifGAshworthNLocal corticosteroid injection for carpal tunnel syndromeCochrane Database Syst Rev20072CD00155417443508

- GurcayEUnluEGurcayAGTuncayRCakciAEvaluation of the effect of local corticosteroid injection and anti-inflammatory medication in carpal tunnel syndromeScott Med J20095414619291926

- BakhtiaryAHRashidy-PourAUltrasound and laser therapy in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndromeAust J Physiother200450314715115482245

- O’ConnorDMarshallSMassy-WestroppNNon-surgical treatment (other than steroid injection) for carpal tunnel syndromeCochrane Database Syst Rev20031CD00321912535461

- ConcannonMJBrownfieldMLPuckettCLThe incidence of recurrence after endoscopic carpal tunnel releasePlast Reconstr Surg200010551662166510809095

- PhalenGSReflections on 21 years’ experience with the carpal-tunnel syndromeJAMA19702128136513675467525

- PfefferGBGelbermanRHBoyesJHRydevikBThe history of carpal tunnel syndromeJ Hand Surg Br198813128343283274

- GerritsenAAUitdehaagBMvan GeldereDScholtenRJde VetHCBouterLMSystematic review of randomized clinical trials of surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndromeBr J Surg200188101285129511578281

- KulickMIGordilloGJavidiTKilgoreESJrNewmayerWL3rdLong-term analysis of patients having surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndromeJ Hand Surg Am198611159663944445

- ScholtenRJMink van der MolenAUitdehaagBMBouterLMde VetHCSurgical treatment options for carpal tunnel syndromeCochrane Database Syst Rev20074CD00390517943805

- HamedARMakkiDChariRPackerGDouble- versus single-incision technique for open carpal tunnel releaseOrthopedics20093210

- OkutsuINinomiyaSTakatoriYUgawaYEndoscopic management of carpal tunnel syndromeArthroscopy19895111182706046

- MackenzieDJHainerRWheatleyMJEarly recovery after endoscopic vs short-incision open carpal tunnel releaseAnn Plast Surg200044660160410884075

- FerdinandRDMacLeanJGEndoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release in bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. A prospective, randomised, blinded assessmentJ Bone Joint Surg Br200284337537912002496

- TrumbleTEDiaoEAbramsRAGilbert-AndersonMMSingleportal endoscopic carpal tunnel release compared with open release: A prospective, randomized trialJ Bone Joint Surg Am200284A71107111512107308

- AtroshiIHoferMLarssonGUOrnsteinEJohnssonRRanstamJOpen compared with 2-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release: A 5-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trialJ Hand Surg Am200934226627219181226

- ChowJCEndoscopic release of the carpal ligament for carpal tunnel syndrome: 22-month clinical resultArthroscopy1990642882962264896

- PalmerDHPaulsonJCLane-LarsenCLPeulenVKOlsonJDEndoscopic carpal tunnel release: A comparison of two techniques with open releaseArthroscopy1993954985088280321

- MurphyRXJrJenningsJFWukichDKMajor neurovascular complications of endoscopic carpal tunnel releaseJ Hand Surg Am19941911141188169354

- AtroshiILarssonGUOrnsteinEHoferMJohnssonRRanstamJOutcomes of endoscopic surgery compared with open surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome among employed patients: Randomised controlled trialBMJ20063327556147316777857

- WongKCHungLKHoPCWongJMCarpal tunnel release. A prospective, randomised study of endoscopic versus limited-open methodsJ Bone Joint Surg Br200385686386812931807

- TessitoreESchonauerCMoraciAMini-open carpal tunnel decompressionNeurosurgery20045541010; author reply 1010.15487071

- HuangJHZagerELMini-open carpal tunnel decompressionNeurosurgery20045423979; discussion 399–400.14744287

- CelloccoPRossiCEl BoustanySDi TannaGLCostanzoGMinimally invasive carpal tunnel releaseOrthop Clin North Am2009404441448vii19773048