Abstract

Wandering spleen is a rare clinical condition which presents with a variety of symptoms with abdominal pain, abdominal mass, and acute abdomen. It may also remain silent until diagnosed by a routine imaging study. Treatment options may differ depending on the presenting clinical picture. Herein we present two cases of wandering spleen treated by splenectomy, with one of them admitted to our emergency clinic with torsion.

Introduction

Wandering spleen (WS) is a rare condition in which the spleen is located anywhere in the abdomen other than in its usual place; however, other terms are used to describe this clinical entity, including “displaced spleen”, “drifting spleen”, “floating spleen”, “pelvic spleen”, “splenic ptosis”, “splenoptosis”, “ectopic spleen”, and “dislocated spleen”. Although it remains enigmatic, the abnormal location of the spleen may be attributed to malformation or total agenesis of the splenic suspensory ligaments because of abnormal development of the dorsal mesogastrium. Therefore, the spleen may either drop into the abdominal cavity and be suspended only by extremely flexible ligaments, or float in the abdominal cavity suspended only by its pedicle. In addition, wandering spleen may occasionallyoccur as a result of weakening of the suspensory splenic ligaments by clinical processes such as trauma, pregnancy, and connective tissue diseases. Splenic torsion, the major complication of WS, was first mentioned in the German literature in 1885. Since then, WS and its clinical aspects have been fully identified, and WS has gradually become a well-known clinical entity.Citation1,Citation2

In this article we report two cases of WS, one of whom presented with torsion. Written informed consent for publication was obtained from both patients.

Case report 1

A 21-year-old female was admitted to our emergency department with an acute abdomen. Apart from abdominal pain continuing for 36 hours, her medical history was insignificant. Physical examination revealed a giant mass located in the left abdominal quadrant, and generalized abdominal tenderness. Routine biochemical parameters were normal except for a moderate leukocytosis (16,500/mm³) and high C-reactive protein (CRP) (80 mg/L). Combined abdominal sonography and contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) demonstrated the absence of a spleen in its normal position, with a 15 × 7 cm solid mass extending from the stomach to the pelvis in the left abdomen that was consistent with WS, and no contrast enhancement within the splenic parenchyma (). An urgent laparotomy revealed a significantly enlarged, infarcted WS secondary to splenic torsion of 540° ( and ). The spleen was suspended by only its pedicle and a few peritoneal adhesions. Splenectomy was performed. The postoperative period was uneventful. The patient was discharged on the fourth postoperative day, to come back for vaccination two weeks later.

Case report 2

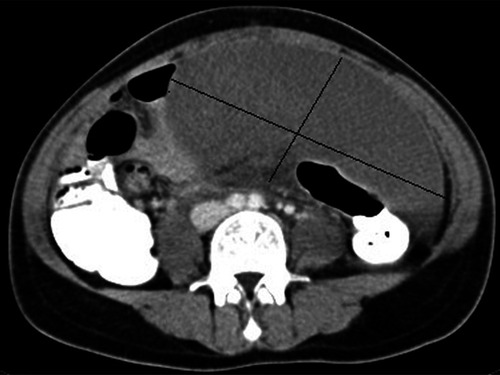

A 19-year-old female was seen in our outpatient clinic with enuresis and vague lower abdominal pain of six months’ duration. She had been treated for urinary tract infection several times within the previous three months. She had an abdominal sonogram because of persistence of her complaints. An enlarged WS of 16 × 6 cm in size extending from the left costal margin to the pelvis was demonstrated on abdominal sonography. Doppler scan showed patent splenic vessels. Contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT scan revealed an enlarged WS extending from the greater curvature to the urinary bladder, and a 3 × 2 cm mass consistent with an accessory spleen (). Because the spleen was enlarged, without any vascular compression, other causes of splenomegaly were investigated. Biochemical, microbiologic, and hematologic tests were all found to be normal. Surgical treatment was considered for management after hematological consultation. During exploratory laparoscopy, an enlarged WS with an accessory spleen at its hilum was found. There were dense adhesions between the WS and the urinary bladder. Given that the accessory spleen was evaluated to be adequate for further splenic function and the spleen was too enlarged to be replaced in its original position, laparoscopic splenectomy was preferred. The postoperative period was uneventful. The patient was discharged on the second postoperative day. The vaccination was deemed to be unnecessary because of the existing accessory spleen.

Discussion

WS is a rarely seen birth defect with an incidence of < 0.2%, caused by an unusually long vascular pedicle which allows migration of the spleen from its normal anatomic position, and is most commonly diagnosed in young children as well as in women between the ages of 20 and 40 years. The first clinical description of WS, confirmed by autopsy, was by Johannes Van Horne, a Dutch physician, in 1667.Citation2–Citation4

The clinical presentation of WS may be variable, from an asymptomatic patient to one with mild abdominal pain, signs of acute abdomen, or acute pancreatitis. The most common symptom of WS is abdominal pain caused by either splenic complications or mass effect. Splenic torsion, the most important complication of WS, may be either acute-complete or intermittent-incomplete. Acute-complete splenic torsion contributes to splenic ischemia in which the patient presents with acute abdominal symptoms, as did our first case. However, intermittent-incomplete splenic torsion may lead to venous congestion and subsequent hypersplenism. Therefore, such patients may present with intermittent or sustained vague abdominal pain, and may be found to have biochemical abnormalities because of hypersplenism,Citation5,Citation6 as did our second case.

Patients with WS may also present with complications associated with other intra-abdominal organs, such as gastrointestinal obstruction secondary to splenic adhesions or a long splenic pedicle, pancreatic necrosis secondary to compression of the pancreatic tail, pancreatitis secondary to displacement of the pancreatic tail into the splenic hilum, bleeding from gastric varices secondary to splenic venous hypertension, and urinary symptoms secondary to compression of the ureters or the urinary bladder. Of note, WS may be asymptomatic with or without a palpable intra-abdominal mass, and is diagnosed incidentally.Citation7–Citation10

The absence of spleen in its normal anatomic position and a presence of an intra-abdominal mass that has similar characteristics with the spleen are major determinants of diagnosis of WS by any imaging modalities utilized. Abdominal sonography and Doppler scan may not only demonstrate a WS but can also evaluate splenic blood flow to rule out a possible splenic torsion.Citation11,Citation12 Contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT scan also provides information about the exact location of WS in relation to other intra-abdominal organs, and the viability of the spleen in the setting of a possible splenic torsion.Citation13 Other diagnostic imaging modalities include radionuclide scan and MRI.Citation14 Combined utilization of abdominal sonography and CT provided a correct diagnosis of WS in our both cases.

Symptomatic patients with WS warrant surgical treatment, but the management of asymptomatic WS remains controversial. However, many authors found a high rate of complications, splenic torsion in particular, associated with conservative treatment.Citation15 Since elective surgical treatment have the advantage of preservation of a viable spleen, surgical treatment seems to be the best option in asymptomatic WS.

Currently, there are two surgical treatment options for WS, ie, splenopexy and splenectomy.Citation16–Citation19 Each procedure can be carried out by open or minimally invasive surgery. The major determinant of the treatment option should be viability of the spleen. Many authors recommend splenopexy in uncomplicated cases, especially in children; however, in cases of infarction due to splenic torsion, splenectomy seems to be the treatment of choice whether laparoscopic or open, depending on the patient’s situation, size of the spleen, and experience of the surgeon.

In conclusion, wandering spleen should be borne in mind for patients presenting with a palpable intra-abdominal mass causing acute or intermittent abdominal symptoms. Emergency intervention is mandatory in cases with torsion. Treatment is almost always surgical with either conventional or minimally invasive approaches.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- MaingotRSplenectomy: Indications and Technique; Abdominal Operation7th ed2New York, NYAppleton-Century-Crofts1980679708

- VargaIGalfiovaPAdamkovMCongenital anomalies of the spleen from an embryological point of viewMed Sci Monit200915RA269RA27619946246

- SoleimaniMMehrabiAKashfiAFonouniHBuchlerMWKrausTWSurgical treatment of patients with wandering spleen: Report of six cases with review of literatureSurg Today20073726126917342372

- StyJRConwayJJThe spleen: Development and functional evaluationSemin Nucl Med1985152762983898381

- LebronRSelfMMangramADunnEWandering spleen presenting as recurrent pancreatitisJSLS20081231031318765060

- FerociFMirandaEMoraldiLMorettiRThe torsion of wandering pelvic spleen: A case reportCases J2008114918783625

- KeidarSFreudMRosenscheinSIntestinal obstruction due to a wandering spleenAm J Gastroenterol197869701714707467

- ShendeACanzkowskyPBeckenJTorsion of a visceroptosed spleenAm J Dis Child197613088911247005

- VermylenCLebecquePClausDThe wandering spleenEur J Pediatr19831401121156884386

- DaneshgarSErasPFeldmanSBleeding gastric varices and gastric torsion secondary to a wandering spleenGastroenterology1980791411436966594

- TaitNPYoungJRThe wandering spleen, an ultrasonic diagnosisJ Clin Ultrasound1985131451463920273

- NakamuraTMoriyasuFBanNQuantitative measurement of abdominal arterial flow using image directed Doppler Ultrasonography: Superior mesenteric, splenic, and common hepatic arterial blood flow in normal adultsJ Clin Ultrasound1989172612682523903

- GayerGZissinRApterSAtarEPortnoyOItzchakYCT findings in congenital anomalies of the spleen. Pictorial reviewBr J Radiol20017476777211511506

- PosillicoLFShahANA wandering spleen. Detection by In-111 leukocyte imagingClin Nucl Med1996212872898925608

- BuehnerBBakerMSThe wandering spleenSurg Gynecol Obstet19921753733871411897

- StringelGSoucyPMercerSTorsion of the wandering spleen: Splenectomy or splenopexyJ Pediatr Surg1982173733757120005

- SeashoreJHMcIntoshSElective splenopexy for wandering spleenJ Pediatr Surg1990252702722303996

- AllenKBAndrewsGPediatric wandering spleen – the case for splenopexy: Review of 35 reported casesJ Pediatr Surg1989244324352661792

- SchmidtSPAndrewsHGWhiteJJThe splenic snood: An improved approach for the management of the wandering spleenJ Pediatr Surg199227104310441403532