Abstract

Patients whose asthma is not adequately controlled despite treatment with a combination of high dose inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting bronchodilators pose a major clinical challenge and an important health care problem. Patients with severe refractory disease often require regular oral corticosteroid use with an increased risk of steroid-related adverse events. Alternatively, immunomodulatory and biologic therapies may be considered, but they show wide variation in efficacy across studies thus limiting their generalizability. Managing asthma that is refractory to standard treatment requires a systematic approach to evaluate adherence, ensure a correct diagnosis, and identify coexisting disorders and trigger factors. In future, phenotyping of patients with severe refractory asthma will also become an important element of this systematic approach, because it could be of help in guiding and tailoring treatments. Here, we propose a pragmatic management approach in diagnosing and treating this challenging subset of asthmatic patients.

Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways characterized by bronchial hyperresponsiveness (BHR), reversible airflow limitation, and recurrent episodes of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough. Asthma is a complex syndrome with many clinical and inflammatory phenotypes.Citation1 Various factors like the environment, genetics, levels of hygiene, and atopic status play a role in the development and progression of asthma phenotypes. Most patients with asthma have mild-to-moderate disease and can be easily controlled by regular use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) combined with short-acting inhaled β2-agonists for relief of symptoms. However, for some patients, asthma continues to be poorly controlled in terms of ongoing symptoms, frequent exacerbations, persistent and variable airway obstruction, and frequent requirement for β2-agonists despite aggressive treatment. Severe or refractory disease remains a frustrating problem for both patients and the clinicians treating them with disproportionately high health-related costs.Citation2–Citation5 A number of clinical definitions have been proposed through national and international guidelines, working groups, which incorporate lung function, exacerbations, and use of high-dose corticosteroids.Citation2,Citation6–Citation8 Of note, is that all these various criteria/guidelines are applicable when patients have had adherence and exacerbations fully addressed.Citation9,Citation10 Many different terms have been used to describe this group of patients with persisting symptoms and frequent exacerbations despite being treated with high-intensity treatment for asthma.

The term problematic severe asthma should be used for all patients who remain uncontrolled despite prescription of high-intensity asthma treatment.Citation11 Apart from patients with true severe refractory asthma (SRA), this group also includes patients with “difficult asthma,” that is uncontrolled asthma for reasons such as persistently poor compliance, psychosocial factors, or persistent environmental exposure to allergens or toxic substances. It also includes patients who have mild – moderate disease that is aggravated by comorbidities such as chronic rhinosinusitis, reflux disease, or obesity. The term severe refractory asthma should be reserved for those patients with severe disease who have been under the care of an asthma specialist for >6 months, and still have poor asthma control or frequent exacerbations despite taking high-dose ICS combined with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) or any other controller medication or for those who can only maintain adequate control by taking oral corticosteroids (OCSs) on a continuous basis, and are thereby at risk of serious adverse effects.

Current asthma guidelines offer little alternatives to OCS for the management of the challenging patient with SRA and these include high-dose ICS combined with LABA, methlyxanthines, antileukotrienes, and omalizumab.Citation12 However, these medications are of variable efficacy and useful only in a limited subset of patients.Citation13 In actual fact, a large number of patients with SRA are on frequent, intermittent, or continuous courses of oral prednisolone (in addition to high-dose ICS combined with LABA) with an increased risk of steroid-related adverse events.Citation14

Here, we review the practical aspects of patients’ management to make sure that patients “labeled” as having SRA truly have SRA, and if so then to discuss the use of add-on therapies both established and novel, including immunological modifiers and biological agents so to propose to physicians a pragmatic management approach in diagnosing and treating this challenging subset of asthmatic patients.

Adherence to medication

Before developing a roadmap in aid of a pragmatic approach in diagnosing and caring for this troublesome condition, it is important to make sure that the issue of adherence is adequately addressed. Poor asthma control can result from poor adherence to treatment;Citation15,Citation16 hence, once the diagnosis of SRA is confirmed then the priority would be exclude compliance to medication as a cause of ongoing symptoms. Detecting poor adherence to medications can be difficult, especially in the busy clinical settings. Ways of checking for adherence may include collection of repeat prescriptions or the measurement of serum prednisolone and cortisol levels in patients on OCS.Citation17 It has been reported in a study that 50% of patients on OCS had low serum levels concentrations of prednisolone and cortisol.Citation18 Although, this seems controversial, it signifies that despite having significant symptoms, these patients with SRA are noncompliant with their medication. Hence, better communication between the patient and physician, and patient education is important.Citation19 Frequent consultations and patient-centered approaches may be useful ways of improving compliance.

There could be a number of reasons for which the patient may not be adhering to their medications: their perception that the treatment is ineffective, delayed effectiveness of medications (ICS), lack of understanding, poor inhaler technique, antipathy towards asthma and its treatment, monetary reasons, psychosocial causes and attention seeking, stress, and forgetfulness.Citation17

Evaluation of severe refractory asthma

There are no validated algorithms to substantiate the most useful approach to the evaluation of the patient with suspected SRA, but some have been suggested.Citation9,Citation10,Citation17 A rational method would involve 3 main aspects:

confirmation of severe asthma

evaluation of other conditions, coexisting conditions and trigger factors

evaluation of the severe asthma subphenotype.

(a) Confirmation of severe asthma

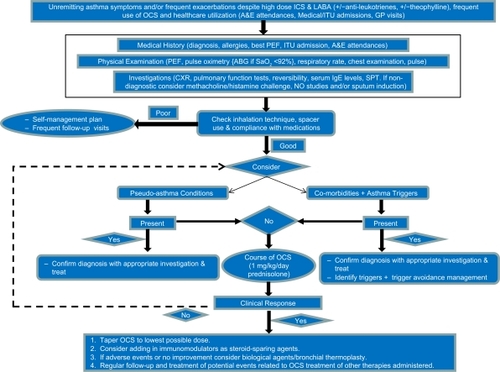

Many aspects need to be considered prior to prescribing add-on treatments and incremental doses of ICS and OCS to patients thought to have SRA. It is necessary to ascertain whether they genuinely have severe asthma (). Hence, first one needs to obtain a detailed history from the patient including details of respiratory symptoms (including chest tightness, wheezing, cough, night and exercise/environmental-related symptoms), the original diagnosis (including who, when, how, and previous investigations), asthma-related morbidity (intensive care/hospital admissions, hospital length of stay, number of exacerbations per year, exacerbating factors, and severity of symptoms), associated comorbidities (including chronic rhinosinusitis disease, cardiac conditions, gastrooesophageal reflux, obesity, and psychological factors), family history, smoking history, and current medication (including compliance, technique, intolerance to medications, and new medications). Second, a thorough physical examination of both respiratory and cardiovascular systems is essential. Third, previous investigations, in particular full blood count, total immunoglobulin E (IgE), autoimmunity, pulmonary function tests, plain chest X-ray, and saturation oximetry (or sometimes arterial blood gases) should be carefully reviewed and if necessary repeated. The pulmonary function tests should include actual and predicted values for forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity, and small airways (forced expiratory flow [FEF25–75]) to document the presence of airflow limitation. Simultaneous assessment of FEV1 reversibility to 400–800 μg inhaled salbutamolCitation20 is helpful. In addition, fall in FEV1 when tapering steroid treatment can be also used to document variable airflow limitation and steroid dependency.

Figure 1 Algorithm summarizing the strategies and mechanisms of managing subjects with suspected severe refractory asthma (SRA).

Occasionally, reversibility testing may not be conclusive and confirmatory tests including bronchial provocation challengesCitation21 (using methacholine or mannitolCitation22), exhaled nitric oxide measurements, and exercise testing may be required. In patients without positive challenge test with bronchial provocation, alternative diagnosis(es) should be considered. Further, more directed investigations to exclude other conditions should be considered to alternative diagnosis(es) be suspected (see later); these may be in addition to or instead of asthma.

(b) Evaluation of other conditions, coexisting conditions and trigger factors

(i) Evaluation of other conditions (pseudoasthma)

Other conditions should be taken in consideration in the differential diagnosis of SRA (). A diagnostic work-up of SRA assumes that these conditions should be excluded systematicallyCitation1,Citation10 Taking a detailed history may arouse suspicion of other conditions and appropriate investigations can confirm or exclude these. These conditions and appropriate investigations include the following ().

Table 1 Examples of diagnostic tools that can assist in distinguishing severe asthma from alternative conditions that may mimic asthma

Bronchiectasis

Taking a detailed history of childhood and partially treated respiratory infections as well as a history of cough, breathlessness, and sputum production may direct you to think of bronchiectasis. On examination, patients may most commonly have crackles, rhonchi, wheezing, and inspiratory squeaks on auscultation. Occasionally, they may also present with digital clubbing, cyanosis, plethora, wasting, and weight loss. A high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan may help to diagnose this.

Interstitial lung disease

Not only a history of progressive breathlessness, but also appropriate history of medication and examination should cause suspicion of interstitial lung disease (ILD). On examination, patients may present with digital clubbing, cyanosis, weight loss, wheezing, end inspiratory fine crepitations, desaturation and breathlessness on exertion, as well as signs of the disease causing the ILD. An HRCT would be helpful diagnostically.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Diagnostic confusion is common between SRA and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), particularly in the middle-aged patient presenting with cough and mild exertional dyspnea who also smokes cigarettes.Citation23 Differentiating between SRA and COPD can be achieved by taking careful patient history and by looking at the appropriate investigations, but neither should be used in isolation to differentiate them.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

Care must be taken to exclude allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) by investigating for specific criteria for diagnosis, some of which include elevated total IgE and specific IgE and/or IgG to Aspergillus fumigatus, positive skin prick test to A fumigatus, and central bronchiectasis on HRCT.Citation24 Delay in diagnosis and treatment may lead to permanent damage to the lungs.

Churg–Strauss vasculitis

The early stage of Churg–Strauss syndrome exhibits substantial overlap with severe asthma, which makes diagnosis difficult. However, unlike severe asthma, Churg–Strauss syndrome may progress into a life-threatening systemic vasculitis, with vascular and extravascular granulomatosis. A diagnosis of Churg–Strauss vasculitis may difficult to tease out as often it manifests a number of overlapping symptoms involving several organ systems.Citation25 Laboratory abnormalities include anemia, persistent eosinophilia, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (in about 30%–50% of cases). Diagnostic confirmation can be obtained by biopsy of the lung or other clinically affected tissues. Like ABPA, prompt diagnosis and treatment are important to avoid irreversible sequel to the lungs. Treatment often includes high-dose OCS and cytotoxic/immunosuppressive therapy.

Vocal cord dysfunction

Vocal cord dysfunction may mimic SRA, presenting with wheezing, cough and breathlessness that is episodic, beginning and remitting abruptly, and nonresponsive to asthma treatments.Citation26 Of note, in these patients expiratory loop and flows are preserved, but inspiratory loop is flattened reflecting reduced flow due to vocal cords partially opposing during inspiration, causing partial flow obstruction. Diagnosis is made by direct visualization of the vocal cords by laryngoscopy when the patient is symptomatic.Citation27

Cardiac disease

Occasionally, congestive heart failure may present with a cardiac wheeze and masquerade SRA.Citation28 On examination, patients may present with tachypnea, crackles on auscultation (normally at the bases), displaced apex beat, elevated jugular venous pressure, and peripheral edema depending on the type of heart failure. Occasionally, they may also present with cyanosis, gallop rhythm, pleural effusions, murmurs, etc. Electrocardiograms, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, echocardiography, and/or cardiac angiography may be helpful to identify any cardiac causes. If a cardiac cause is proved, treatment would obviously be directed towards this and not increase antiasthma medications.

(ii) Evaluation of coexisting conditions and trigger factors

It has been reported that other conditions can coexist alongside severe asthma, and these may present, if untreated, with asthma-like symptoms.Citation18,Citation28 Hence, coexisting conditions need to be carefully identified and managed, as it may improve the patients’ symptoms and prevent further escalation of asthma medications (). Remember, taking a detailed history may arouse suspicion other comorbidities or appropriate investigations confirm these. Some of these conditions and appropriate investigations are as follows.

Chronic rhinosinusitis

Chronic rhinosinusitis is frequently associated with SRACitation29,Citation30 and nasal polyposis is often related to aspirin (and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) intolerance and a more severe asthma phenotype.Citation31–Citation33 Symptoms of rhinosinusitis include nasal congestion and obstruction, purulent nasal discharge, maxillary tooth discomfort, and facial pain or pressure. Other signs and symptoms include fever, fatigue, cough, hyposmia or anosmia, ear pressure or fullness, headache, and halitosis. Diagnosis is confirmed by nasal endoscopy and computed tomography-imaging of the sinuses. Medical (nasal and/or systemic corticosteroids, immunotherapy, antihistamines, and antibiotics) or surgical treatment of upper airway disease can improve asthma control. Therefore, patients with severe asthma should be systematically evaluated and treated for rhinosinusitis with or without nasal polyps ().

Table 2 Diagnostic tools and treatment of most common comorbidities in severe asthma

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is common among patients with asthma, but often causes mild or no symptoms. Although it has been suggested as a pathophysiological link between gastroesophageal reflux and asthma, the exact relationship between the 2 conditions has not been fully established.Citation34 GERD may be suspected in patients with heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia. Less common symptoms include odynophagia, excessive salivation, nausea, chest pain, chronic cough, laryngitis, erosion of dental enamel, and hypersensitivity. Although detection of GERD is ideally obtained by 24-hour pH monitoring, many physicians prefer to give an empiric therapy trial of ≥3 months with high-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPI; ). PPIs have shown to reduce asthma symptoms in some studies,Citation35,Citation36 but not in others.Citation37,Citation38 Treatment with PPI does not improve asthma control and is unlikely to be the cause of the poorly controlled asthma.Citation38 No specific studies have been carried out in the subset of patients with SRA.

Psychosocial factors

Subjects with asthma are more likely to be treated for a mental health problem (depression, anxiety, and panic disorders) and demonstrate more negative social outcomes.Citation39 This is more so if the patient has severe disease or has had a life-threatening episode.Citation17,Citation40 In addition, anxiety disordersCitation41 and acutely negative affective disordersCitation42 have also been shown to have an impact on asthma. In an open-labeled study of 75 patients with SRA, it was reported that 33 had a psychiatric element to their asthma and in 10 of those this was thought to be “major.”Citation18 Specialist help from a psychiatrist is needed to establish the correct diagnosis and its significance. However, it is still controversial as to whether treatment of the psychological condition may lead to an overall improvement in asthma control and severity.

Drugs

Various drugs can provoke an asthma attack or worsening asthma symptoms. Some of these include β-blockers, aspirin, NSAIDs,Citation18 angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, and estrogens. Likewise, food intolerances can have similar effects on asthma control.

Smoking

Cigarette smoking has multiple negative effects on asthma. Accelerated decline in lung function over time is present in asthmatic individuals who smoke.Citation43 Smokers with asthma are more symptomatic and have more severe and frequent exacerbations and emergency care needs.Citation44 Asthma mortality is greater among asthmatics who smoke cigarettes compared with asthmatics who do not smoke.Citation45 In addition, asthmatic patients who smoke appear to have a reduced therapeutic response to both inhaled and OCSs.Citation46,Citation47 Last but not least, recent research has shown that cigarette smoking is an important independent risk factor for new onset asthma in allergic individuals.Citation48 Hence, smoking cessation is also critical in the management of the patient with SRA who smokes.

Allergens and trigger factors

Unusual asthma triggers is a vital component that requires addressing and may be helpful in managing the patient. Triggers could be exogenous or endogenous, the latter of which can be related to the comorbidities discussed early, such as respiratory infections, gastroesophageal reflux, psychological triggers, etc. Exogenous factors include allergensCitation49 or occupational/domestic sensitizers that may boost the inflammatory response of the underlying asthma and enhance BHR, thus contributing to the severe asthma phenotype.Citation1 A recent study has reported that specific work environments are associated with the development of severe asthma.Citation50 Dissecting out the individual role of exogenous or endogenous factors requires a high level of suspicion and great skills in history taking.

Obesity

The European Network for Understanding Mechanisms of Severe Asthma study has reported that patients with more severe disease are women with a component of irreversible airflow obstruction, neutrophilic inflammation, reduced atopy, and with a larger body mass index.Citation2 There is also accumulating evidence that obese patients have an increased risk of developing asthma.Citation51 Although asthma and obesity are frequently associated, the contribution of obesity to severe asthma as well as the mechanisms responsible for this relationship are not fully clarified. Although morbid obesity is positively associated with reduced lung volumes and the presence of comorbid aggravating factors, including gastric reflux, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and psychological factors,Citation52 the overall strength of the relationship between obesity and severe asthma appears to be modestCitation53 (). Although the evidence that weight control interventions are associated with improvements in asthma control remains controversial,Citation54,Citation55 weight reduction should be strongly encouraged anyhow.

(c) Evaluation of severe asthma subphenotype

By systematically addressing conditions and factors according to the diagnostic work-up illustrated earlier, it is possible to define patients with truly SRA. However, this subgroup is far from being homogeneous and may be further subdivided into different phenotypes. Phenotyping of patients with SRA is becoming increasingly important because it may help to guide current and possibly future treatments. However, the true significance of phenotyping SRA can be firmly established only when detailed characterization of hundreds of patients will be completed and analyzed, as proposed in the newly established pan-European consortium Unbiased Bio-markers for the Prediction of Respiratory Disease Outcome funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative in its program Understanding Severe Asthma.Citation56

In clinical practice, most patients with severe asthma are by and large belonging to 3 categories: (1) those suffering from frequent severe exacerbations with relatively stable episodes between exacerbations (exacerbation prone asthma), (2) those who develop irreversible airflow obstruction (asthma with fixed airflow obstruction), and (3) those who depend on systemic corticosteroids for daily control of their asthma (steroid-dependent asthma).Citation10

From a pathological point of view at least 2 phenotypes of severe asthma have been proposed, each associated with distinct clinical and pathophysiological characteristics. These subtypes include the persistent eosinophilic and noneosinophilic forms of severe asthma.Citation57

Management of severe refractory asthma

Treatment of SRA remains highly problematic and regular systemic corticosteroids are often needed to minimize symptoms. Hence, SRA patients not only are at risk of dying from their asthma, but also from the comorbidities associated with the excessive steroid use.Citation7,Citation58 Patients with such severe disease that is unremitting to guideline-based management may be better looked after at dedicated clinics where patients would be assessed for alternative diagnoses and comorbidities, adequately phenotyped using more specialized investigative methods, and optimally managed with the best possible treatments available, and where patients may also have facilitated access to a multidisciplinary team (physicians, ear, nose, and throat specialists, psychologists, pharmacists, and specialist nurses).Citation17 However, only a few tertiary asthma centers are available.Citation59

Optimal treatment of SRA should be aimed at achieving the best possible asthma control and quality of life (Qol) with the least dose of medication (particularly systemic corticosteroids). The choice and formulation of therapeutic agents to be used should be dictated by disease severity, therapeutic response, patient’s comorbidities and preferences, as well as on the agents’ adverse event profile. These include:

standard therapies

immunomodulatory agents

biological and other novel therapies.

Standard therapies

Standard treatment for patients with severe asthma includes high-dose ICS (≥1,200 μg/day or equivalent of beclomethasone) in combination with a LABA. There are a number of combined inhalers in the market that can also used with a spacer device.Citation6 Therefore, if a patient has not been on high-dose ICS (along with LABA), a trial is certainly warranted.Citation60 More recently, there have been suggestions that an ICS with smaller particle size for more distal penetration of the airways to improve inflammation in smaller airways has been proposed, but its efficacy has yet to be evaluated in SRA.Citation9 Although it has been reported that the use of LABA may reduce the dose of ICS by 57%,Citation61 they may not be as efficacious in patients with SRA than in moderate persistent asthma.Citation62,Citation63 Leukotriene antagonists may be beneficial in some patients with severe asthma, especially those with aspirin sensitivity.Citation2,Citation64 Other drugs used in which reports of improvements in patients with SRA, but not assessed by randomized clinical trials, include anticholinergics,Citation65,Citation66 theophyllines,Citation67,Citation68 and intravenous (IV) magnesium.Citation69,Citation70 Hence, a trial of these agents may prove useful.

Inspite of using these additional therapies, there is a subgroup of patients with severe unremitting disease who require high doses of OCS (≥30 mg/day) on a daily basis to attain an adequate level of control of their symptoms and QoL. This subgroup of patients often exhibits deterioration of their asthma symptoms as soon as the dose of corticosteroids is tapered. Hence, reasonable control of their asthma can only be achieved at the cost of significant morbidity (eg, osteoporosis, diabetes, hypertension, cataract formation, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, myopathy, adrenal insufficiency, susceptibility to infections, weight gain, and skin thinning).Citation71,Citation72

Immunomodulatory drugs

To curtail the necessity of prolonged OCS use and the adverse effects associated, a trial with immunomodulatory drugs may be an option. Some of the agents that can be considered include methotrexate, cyclosporine A, and macrolide antibacterials.Citation13 Other agents have been investigated but are not commonly used and include azathioprine, gold, and IV IGs.Citation13 We shall discuss the former 3 agents as they have been more commonly tried as corticosteroid-sparing agents in severe asthma (see for summary).

Table 3 Summary of evidence of efficacy of the immunomodulatory, biological, and other therapies in severe refractory asthma

Methotrexate

Methotrexate is a folic acid inhibitor, but at low doses has immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties.Citation73 Methotrexate is the most clinically investigated immunological agents in severe asthma. In total, there have been 11 well-conducted clinical trials published in the literature to evaluate the efficacy and safety of methotrexate in SRA.Citation13 The trials involved the use of methotrexate administered orally at dose of 7.5–30 mg on a weekly basis for a period between 12 and 24 weeks in patients who were mostly taking >10 mg of prednisolone daily. Some of them had run-in periods and were either placebo-controlled crossover (PCC) or double-blind placebo-controlled studies (DBPC). Only one of the studies had patients on methotrexate for a period of 12 months.Citation74 Of all the studies, the 3 larger ones showed that the administration of methotrexate had a significant reduction in the OCS dose.Citation74–Citation76 None-life-threatening adverse events that were transient and reversible on stopping methotrexate administration including abnormal liver function tests, GI symptoms, oral ulcers, and stomatitis were noted. Of note, in 2 separate prospective open-labeled extension studies for up to 28 weeks, oral methotrexate at 15 mg weekly were reported to result in a significant OCS dose reduction, and in fact more than half of the patients came off their OCS completely.Citation77,Citation78 In addition, in a large case series of patient with SRA treated with low dose methotrexate for up to 12 years it has been shown a substantial, safe decrease in OCS (OCSs were withdrawn completely in 59% of patients).Citation79 Taken together, these findings show that prolonged administration of methotrexate will be necessary to achieve significant OCS reduction or to wean off OCS completely.

Three meta-analyses have been published in the literature on methotrexate in SRA of the a number of the 11 studies conducted showing a small but significant OCS dose reduction with use of methotrexate.Citation80–Citation82 Also, no other subjective or objective parameters have been noted to be significantly altered with the administration of methotrexate. Although there were no predicting factors in the “responders,” these studies have shown that there are some subgroups of SRA patients who have benefited from the use of oral methotrexate. Hence, as in the treatment of rheumatological and dermatological conditions, the risk–benefit profile of methotrexate is preferable to that of the long-term use of OCS at doses >10 mg/day; thus, we recommend that methotrexate should be the first choice of steroid-sparing immunomodulator therapy for patients with SRA.

Cyclosporine A

Cyclosporine A works by inhibiting the activation of T cells. T cells have been implicated in the pathogenesis of asthma and hence the drive to investigate its efficacy in asthma.Citation83–Citation86 To date, there have been 3 published studies of the use of cyclosporine A at a dose of 5 mg/kg/day in SRA patients on a mean dose of >8.5 mg/day of prednisolone in the literature (2 DBPCCitation87,Citation88 and 1 PCCCitation89) for a period of 12–36 weeks. Among the 3 studies conducted, there were significant improvements in lung function, symptom scores, and reliever use; however, all 3 studies reported a significant reduction in OCS dose in the patients. Although in the conducted studies only minor adverse events of mild renal impairment, worsening of preexisting hypertension, paraesthesia, tremor, headaches, flu-like illness, and increased hypertrichosis were noted, these reversed on stopping the cyclosporine A.Citation87–Citation91 Notably, there is always the dose-dependent nephrotoxicity concern based on the experience of transplant literature.

A meta-analysis of 3 studies using cyclosporine A in SRA has reported that the use of cyclosporine A is associated with a minor reduction in the OCS dose in these patients,Citation92 but this is on the background of safety concerns of worsening hypertension and renal function. Furthermore, although we do not have any long-term studies in SRA, long-term use in other chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are burdened by substantial failure rates.Citation93,Citation94 Hence, not only do patients require close monitoring but also the risk of failure with cyclosporine A. With this in mind, future studies should be conducted with the use of newer cyclosporine A analogs, tacrolimus, and pimecrolimus, which have better safety profiles and more efficacious in corticosteroid-resistant conditions.

Macrolide antibacterials

Originally, macrolides (eg, troleadomycin) have been used in SRA, not for their antibacterial properties but for their steroid-sparing effects.Citation95,Citation96 Important benefits have also been noted with newer macrolides based on their anti-inflammatory effects.Citation97,Citation98 Three DBPC studiesCitation99–Citation101 have looked into the safety and efficacy of troleadomycin in patients with OCS-dependent asthma, of which 2 were small and conducted in children.Citation99,Citation100 These latter 2 small studies reported substantial OCS dose reduction use and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR).Citation99,Citation100 In the larger study that spanned 12 months, 75 SRA patients on OCS were recruited and reported in those that completed the study that there was a significant reduction in OCS daily use; however, this was not associated with a reduction in the number of emergency department (ED) attendance and admissions, asthma control, and AHR.Citation101 Newer macrolides have been used demonstrating not only similar reductions in daily OCS use or weaning off OCS completely, but also airway inflammation and subjective parameters.Citation102–Citation104 Troleadomycin, with its steroid metabolism activity on the cytochrome P450 complex was associated with not only increased the steroid-related adverse events, but also direct events such as GI symptoms and hepatotoxicity ranging from transient liver enzyme abnormalities to cholestatic jaundice; hence, its use has been discontinued. However, the use of clarithromycin has not been associated with any major adverse events in the published literature.

Although initial data on the use of clarithromycin show that there is some benefit in the use of macrolides in SRA, more robust, well-conducted DBPC studies are needed to evaluate their true value.

Biologics and other therapies

Due to the refractoriness to OCS and/or immunomodulators, or adverse events to the latter novel strategies have been developed to evaluate alternative therapies in these SRA patients. These may be useful in a steroid-sparing or steroid-replacement role. These include the licensed omalizumab, and other drugs that have not been so efficacious or safe, and others with only small DBPC trial data (see for summary).

Omalizumab

IgE has central pathophysiological role in the development of allergic conditions by enhancing dendritic cell allergen uptake, and activation and release of inflammatory mediators by mast cells and basophils.Citation105,Citation106 Omalizumab is a humanized IgE-specific monoclonal antibody that prevents interaction of IgE to FcɛR1 receptors on effector cells.Citation107,Citation108 Early pharmacodynamic studies have reported that omalizumab reduces inflammation, AHR, and allergen-induced airway and skin tests.Citation109,Citation110

There have been 6 large DBPC studies, evaluating over 2,500 patients, that have been conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of omalizumab in severe atopic asthmatics who had persisting symptoms despite optimum treatment.Citation111 Omalizumab is administered either 2-weekly or 4-weekly depending on the weight and IgE levels, in patients with an IgE level between 30–700 IU/ml over 25–52 weeks in the various studies. Pooled analyses of the studies have reported that the addition of omalizumab has beneficial improvements in the reduction of exacerbations, reduction in ED attendances, asthma-related QoL, asthma symptoms, lung function as well as reduction in steroid reliever usage.Citation111–Citation115 Also reported was that the therapeutic response of omalizumab is best assessed at 16 weeks after initiation to justify its continuation. In addition, compared with placebo, patients treated with omalizumab did not have significantly more adverse events. Most of the adverse events were minor such as headaches, cough, GI symptoms, urticaria, and injection-site reactions.Citation116 There have been postmarketing reviews suggesting that there are slightly increased number of anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions, malignant neoplasms, and helminth infections in patients treated with omalizumab and that caution and vigilance of these need to be in the clinicians mind.Citation105,Citation116,Citation117

The number of patients with severe atopic asthma is small and it is only in around two-thirds of these that omalizumab may be effective and hence the 16-week and regular assessment of its efficacy and safety need to be in reviewed, but also that the large majority of SRA patients are nonatopic and hence the use of omalizumab may be a limited option. Besides, the use of omalizumab is not licensed in severely atopic patients and its cost is a limiting feature. In England, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence advises the use of omalizumab in patients who have had 2 or more ED attendances and/or hospital admission due to lack of control of their asthma despite optimal therapy.Citation105 Other criteria include atopy to at least a common allergen, and compliance and adherence to asthma medications.

Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha drugs

Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) is a multifunctional proinflammatory TH1 cytokine. Corticosteroids fail to reduce TNF-α and TH1 cytokines in asthmatic airways and hence explain the lack of steroid efficacy in these severe asthma patients.Citation118 TNF-α has been implicated in the various pathological processes of asthma.Citation119 Hence, the trial of anti-TNF-α agents in SRA was considered. Importantly, anti-TNF-α agents are widely used in other TH1-mediated chronic conditions such as RA, psoriasis, Crohn disease, and ankylosing spondylitis with good efficacy and safety.Citation120

In mild and moderate asthma, anti-TNF-α treatment has proved to be noneffective.Citation121,Citation122 Two initial small studies of anti-TNF-α treatment, using the soluble receptor etanercept, showed that there were marked improvements in subjective (asthma-related control and QoL) as well as objective (spirometry, peak flows, and AHR) measures of asthma and reduction in reliever medication use.Citation123,Citation124 More recent larger studies using etanerceptCitation125 and the monoclonal antibody, golimumab,Citation126 have shown that there were minimal or no important changes in asthma measures. In fact, in the latter study the trial was terminated early due to the increased number of patients who developed solid malignancies and serious infections. Safety of anti-TNF-α agents comes mainly from studies of rheumatological conditions, including increased risk of malignancies, opportunistic infections and reactivation of tuberculosis, demyelination, and cardiac failure.Citation119,Citation127 In the asthma studies besides the major adverse events noted in the golimumab study, only minor adverse events were noted including injection-site reactions, rashes, respiratory tract and asthma exacerbations, and headaches.Citation122–Citation125

The role of anti-TNF-α agents in severe asthma, although initially looked promising, were darkened by the outcomes of the larger studies both in terms of efficacy and safety. Of note, there are floors in the larger studies including recruiting of milder patients, short treatment, and observation periods. It also seems that the soluble receptor, etanercept, is associated with less severe adverse event and more efficacy.

However, in view the findings of anti-TNF-α agents are no longer under trial or use in severe asthma.

Mepolizumab (anti-IL-5)

Th2 cytokines, namely interleukin (IL)-4, 4, 5, 9, 13 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, are expressed in elevated amounts in severe disease.Citation128 Monoclonal IL-5 antagonists have been studied in varying severities of asthma, but have not shown any symptom or physiological improvements.Citation129–Citation132 However, they have shown significant reductions in circulating, bone marrow and airway eosinophilia, trend towards reduced risk of moderate/severe exacerbations and attenuation of airway remodeling.Citation131,Citation133

In a recent study, Haldar et alCitation134 studied the efficacy of anti-IL-5 therapy using mepolizumab in patients with eosinophilic refractory asthma in DBPC fashion for 12 months. They reported a significant reduction in severe asthma exacerbations (primary outcome) and associated reductions in blood and sputum eosinophilia. Akin to previous studies, there were no significant changes in subjective or objective markers of asthma, but there was a small significant reduction in percentage (not actual) steroid usage in the mepolizumab group compared with placebo. The beneficial effects of mepolizumab have also been shown in another prednisolone withdrawal study in severe eosinophilic asthma.Citation135 The use of mepolizumab was not associated with any significant major or minor adverse events compared with placebo.

These 2 studies show that in a small subgroup of patients with asthma who continue to have sputum eosinophilia even after treatment with OCS and high-dose ICS, treatment with mepolizumab may be effective in reducing asthma exacerbations, steroid use, and potential airway remodeling; however, this needs to be confirmed in larger studies in patients within this specific subgroup.

Daclizumab (anti-CD25)

It is well known that airway inflammation in asthma involves T-cell activation. It has been reported that there are increased number of activated CD25+ T cells and increased levels of IL-2 and soluble (s) IL-2 receptor alpha chain (sCD25) found in the airways of patients with severe asthma.Citation136–Citation139 Following T-cell activation, cytokine generation and secretion may contribute to the initiation and potentiation of inflammation along with the development of repair leading to airway remodeling.Citation138 Daclizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody to alpha (CD25) subunit of the high-affinity IL-2 receptor, inhibiting IL-2 binding and thus IL-2’s biological activity.

In a DBPC study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of daclizumab in moderate to severe patients with asthma, it was reported that there were small, but significant improvements in FEV1, daytime asthma symptoms, and prolonging of time to exacerbation in the patients on daclizumab compared with controls.Citation140 Also, there was marked reduction in reliever use in favor of patients on daclizumab. Although there were no differences in mild and moderate adverse events between the 2 study groups (upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, nasal congestion, rash, and nausea), there were more patients with serious adverse events in the daclizumab group including anaphylactoid reaction, viral meningitis, exacerbation of UC, and diabetics.

This small study demonstrates that daclizumab may have a role in asthma and further studies are needed to define its role as an add-on therapy.

Bronchial thermoplasty

An increase in airway smooth muscle (ASM) is thought to be an important factor in severe and fatal asthma.Citation141,Citation142 Bronchial thermoplasty (BT) is the delivery of controlled thermal energy to the airway wall during several bronchoscopy procedures. The application of BT to the airways is an innovative treatment approach to reduce the bronchoconstrictor response in asthma. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that BT results in reduction of the ASM,Citation143,Citation144 and animal models have been associated with a long-lasting reduction in AHR.Citation143

In a proof-of-concept study in 16 patients with mild-to-moderate asthma, it was confirmed that BT results in an improvement in symptom-free days and peak expiratory flow (PEF) at 3 months, and an improvement in AHR with an associated reduction in asthma symptoms and no adverse events for a period of 2 years.Citation145 In the Asthma Intervention Research (AIR) trial, which was to assess the efficacy of BT in patients with moderate to severe asthma, it was observed that following BT patients had significantly reduced mild exacerbations and use of reliever medication, improvement in morning PEF, asthma-related QoL, and control compared with controls.Citation146 Post hoc analysis suggested that the benefits were greatest in patients with more severe disease. Hence, in a smaller study (Research in Severe Asthma [RISA]) similarly designed to the AIR study, BT was administered in patients with severe asthma and showed similar improvements in outcomes to the AIR study.Citation147 In both studies (AIR and RISA), there were notable adverse effects of BT and lack of effect on AHR. The significant increased respiratory adverse effects included wheezing, cough, chest discomfort, dyspnoea, productive cough, and discolored sputum in the BT group compared with control. Although both these studies showed improvement in asthma outcomes, there was prudence of the high placebo effect. Thus another study, AIR2, was conducted in severe asthma patients in whom a sham procedure was conducted to overcome the placebo effect.Citation148 At 6–12 months post-treatment, BT had a small, but significantly improved asthma-related QoL score compared with sham control. Of note, there are no differences between the 2 treatments in any of the secondary outcome measures, but safety assessments showed less (but nonsignificant) severe exacerbations and ED attendances in the BT group compared with the sham control group.

Overall, the AIR2 study has demonstrated disappointing outcomes for BT. Severe asthma has many phenotypes, and in which phenotype BT may be efficacious requires further work. Also, the risk–benefit ratio of BT in these patients with steroids refractory disease needs to be assessed.

Conclusion and the future

Managing asthma that is refractory to standard treatment requires a systematic approach to evaluate adherence, ensure a correct diagnosis, and identify coexisting disorders and trigger factors. In future, phenotyping of patients with SRA will also become an important element of this systematic approach, because it could be of help in guiding and tailoring treatments.

Treatment of SRA remains highly problematic and regular systemic corticosteroids are often needed to minimize symptoms. Despite the unquestionable beneficial role of systemic corticosteroids for most patients with SRA, they do not seem to be effective in every patient and they are associated with severe adverse side effects. Moreover, immunomodulatory and biologic therapies reportedly lack high levels of efficacy, show wide variation in success rates across studies, and are associated with adverse side effects.

Consequently, there is a compelling need for more effective drugs for these challenging patients. Identifying medications that reduce the need for systemic corticosteroids in patients with SRA should be a priority for the academic world and the pharmaceutical industry.

Disclosure

Riccardo Polosa has participated as a speaker for CV Therapeutics, Novartis, Merck and Roche. He is also a consultant for CV Therapeutics, Duska Therapeutics and NeuroSearch.

References

- HolgateSTPolosaRThe mechanisms, diagnosis, and management of severe asthma in adultsLancet2006368953778079316935689

- The ENFUMOSA cross-sectional European multicentre study of the clinical phenotype of chronic severe asthmaEuropean network for understanding mechanisms of severe asthmaEur Respir J200322347047714516137

- Van GanseELaforestLPietriGPersistent asthma: disease control, resource utilisation and direct costsEur Respir J200220226026712212953

- AntoncelliLBuccaCNeriMDe BenedettoFSaabbataniPBFAsthma severity and medical resource utilizationEur Respir J20042372372915176687

- GodardPChanezPSiraudinLNicoloyannisNDuruGCosts of asthma are correlated with severity: a 1-yr prospective studyEur Respir J2002191616711843329

- Global Initiative for Asthma Global strategy for asthma management and preventionA six part management program NIH publication number 02-36592006

- ChungKFGodardPAdelrothEDifficult/therapy-resistant asthma: the need for an integrated approach to define clinical phenotypes, evaluate risk factors, understand pathophysiology and find novel therapies. ERS Task Force on Difficult/Therapy-Resistant Asthma. European Respiratory SocietyEur Respir J19991351198120810414427

- WenzelSFahyJVIrvinCGPetersSPSpectorSSzeflerSJProceedings of the ATS Workshop on Refractory Asthma: current understanding, recommendations and unanswered questionsAm J Respir Crit Care Med20001622341235111112161

- WenzelSSevere asthma in adultsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005172214916015849323

- PolosaRBenfattoGTManaging patients with chronic severe asthma: rise to the challengeEur J Intern Med200920211412419327598

- ChanezPWenzelSEAndersonGPSevere asthma in adults: what are the important questions?J Allergy Clin Immunol200711961337134817416409

- GINA Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention NIH publication number 02-3659.2009

- PolosaRMorjariaJImmunomodulatory and biologic therapies for severe refractory asthmaRespir Med2008102111499151019012848

- BucknallCESlackRGodleyCCMackayTWWrightSCScottish Confidential Inquiry into Asthma Deaths (SCIAD), 1994–6Thorax1999541197898410525555

- BenderBGOvercoming barriers to nonadherence in asthma treatmentJ Allergy Clin Immunol2002109Suppl 6S554S55912063512

- WeinsteinAGShould patients with persistent severe asthma be monitored for medication adherence?Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol200594225125715765741

- CurrieGPDouglasJGHeaneyLGDifficult to treat asthma in adultsBMJ2009338b49419240094

- RobinsonDSCampbellDADurhamSRPfefferJBarnesPJChungKFSystematic assessment of difficult-to-treat asthmaEur Respir J200322347848314516138

- CochraneGMHorneRChanezPCompliance in asthmaRespir Med1999931176376910603624

- MooreWCBleeckerERCurran-EverettDCharacterization of the severe asthma phenotype by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research ProgramJ Allergy Clin Immunol2007119240541317291857

- British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline NetworkBritish guideline on the management of asthmaThorax200863Suppl 4iv1iv12118463203

- CrapoROCasaburiRCoatesALGuidelines for methacholine and exercise challenge testing-1999. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999Am J Respir Crit Care Med2000161130932910619836

- TinkelmanDGPriceDBNordykeRJHalbertRJMisdiagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care patients 40 years of age and overJ Asthma2006431758016448970

- GreenbergerPAAllergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, allergic fungal sinusitis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitisClin Allergy Immunol20021644946811577554

- NothIStrekMELeffARChurg – Strauss syndromeLancet2003361935758759412598156

- GoldmanJMuersMVocal cord dysfunction and wheezingThorax19914664014041858076

- WoodRP2ndMilgromHVocal cord dysfunctionJ Allergy Clin Immunol19969834814858828523

- HeaneyLGConwayEKellyCPredictors of therapy resistant asthma: outcome of a systematic evaluation protocolThorax200358756156612832665

- ten BrinkeAGrootendorstDCSchmidtJTChronic sinusitis in severe asthma is related to sputum eosinophiliaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2002109462162611941310

- BrescianiMParadisLDes RochesARhinosinusitis in severe asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol20011071738011149994

- MasciaKHaselkornTDenizYMMillerDPBleeckerERBorishLAspirin sensitivity and severity of asthma: evidence for irreversible airway obstruction in patients with severe or difficult-to-treat asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2005116597097516275362

- CorrenJAllergic rhinitis and asthma: how important is the link?J Allergy Clin Immunol1997992S781S7869042071

- CeylanEGencerMSanINasal polyps and the severity of asthmaRespirology200712227227617298462

- FieldSKUnderwoodMBrantRCowieRLPrevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in asthmaChest199610923163228620699

- LittnerMRLeungFWBallardED2ndHuangBSamraNKEffects of 24 weeks of lansoprazole therapy on asthma symptoms, exacerbations, quality of life, and pulmonary function in adult asthmatic patients with acid reflux symptomsChest200512831128113516162697

- KiljanderTOHardingSMFieldSKEffects of esomeprazole 40 mg twice daily on asthma: a randomized placebo-controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006173101091109716357331

- LeggettJJJohnstonBTMillsMGambleJHeaneyLGPrevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in difficult asthma: relationship to asthma outcomeChest200512741227123115821199

- MastronardeJGAnthonisenNRCastroMEfficacy of esomeprazole for treatment of poorly controlled asthmaN Engl J Med2009360151487149919357404

- CollinsJEGillTKChittleboroughCRMartinAJTaylorAWWinefieldHMental, emotional, and social problems among school children with asthmaJ Asthma200845648949318612902

- MilesJFGardenGMTunnicliffeWSCaytonRMAyresJGPsychological morbidity and coping skills in patients with brittle and non-brittle asthma: a case-control studyClin Exp Allergy19972710115111599383255

- Roy-ByrnePPDavidsonKWKesslerRCAnxiety disorders and comorbid medical illnessGen Hosp Psychiatry200830320822518433653

- KullowatzARosenfieldDDahmeBMagnussenHKanniessFRitzTStress effects on lung function in asthma are mediated by changes in airway inflammationPsychosom Med200870446847518480192

- LangePParnerJVestboJSchnohrPJensenGA 15-year follow-up study of ventilatory function in adults with asthmaN Engl J Med199833917119412009780339

- EisnerMDIribarrenCThe influence of cigarette smoking on adult asthma outcomesNicotine Tob Res200791535617365736

- MarquetteCHSaulnierFLeroyOLong-term prognosis of near-fatal asthma. A 6-year follow-up study of 145 asthmatic patients who underwent mechanical ventilation for a near-fatal attack of asthmaAm Rev Respir Dis1992146176811626819

- ChaudhuriRLivingstonEMcMahonADThomsonLBorlandWThomsonNCCigarette smoking impairs the therapeutic response to oral corticosteroids in chronic asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med20031168111308131112893649

- TomlinsonJEMcMahonADChaudhuriRThompsonJMWoodSFThomsonNCEfficacy of low and high dose inhaled corticosteroid in smokers versus non-smokers with mild asthmaThorax200560428228715790982

- PolosaRKnokeJDRussoCCigarette smoking is associated with a greater risk of incident asthma in allergic rhinitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol200812161428143418436295

- CurrieGPJacksonCMLeeDKLipworthBJAllergen sensitization and bronchial hyper-responsiveness to adenosine monophosphate in asthmatic patientsClin Exp Allergy200333101405140814519147

- Le MoualNSirouxVPinIKauffmannFKennedySMAsthma severity and exposure to occupational asthmogensAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005172444044515961697

- SinDDSutherlandERObesity and the lung: 4. Obesity and asthmaThorax200863111018102318984817

- van VeenIHten BrinkeASterkPJRabeKFBelEHAirway inflammation in obese and nonobese patients with difficult-to-treat asthmaAllergy200863557057418394131

- CamargoCAJrWeissSTZhangSWillettWCSpeizerFEProspective study of body mass index, weight change, and risk of adult-onset asthma in womenArch Intern Med1999159212582258810573048

- HakalaKStenius-AarnialaBSovijarviAEffects of weight loss on peak flow variability, airways obstruction, and lung volumes in obese patients with asthmaChest200011851315132111083680

- Stenius-AarnialaBPoussaTKvarnstromJGronlundELYlikahriMMustajokiPImmediate and long term effects of weight reduction in obese people with asthma: randomised controlled studyBMJ2000320723882783210731173

- http://www.fp7-consulting.be/en/ubiopred/.2008

- WenzelSESchwartzLBLangmackELEvidence that severe asthma can be divided pathologically into two inflammatory subtypes with distinct physiologic and clinical characteristicsAm J Respir Crit Care Med199916031001100810471631

- ItoKChungKFAdcockIMUpdate on glucocorticoid action and resistanceJ Allergy Clin Immunol2006117352254316522450

- RobertsNJRobinsonDSPartridgeMRHow is difficult asthma managed?Eur Respir J200628596897316807267

- NoonanMChervinskyPBusseWWFluticasone propionate reduces oral prednisone use while it improves asthma control and quality of lifeAm J Respir Crit Care Med19951525 Pt 1146714737582278

- GibsonPGPowellHDucharmeFLong-acting beta2-agonists as an inhaled corticosteroid-sparing agent for chronic asthma in adults and childrenCochrane Database Syst Rev20054CD00507616235393

- NightingaleJARogersDFBarnesPJComparison of the effects of salmeterol and formoterol in patients with severe asthmaChest20022151401140612006420

- GuyerBGibbsRFeldsienDWenzelSA pilot study to evaluate the bronchodilator response pattern to salmeterol in refractory asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2002109S244

- TonelliMZingoniMBacciEShort-term effect of the addition of leukotriene receptor antagonists to the current therapy in severe asthmaticsPulm Pharmacol Ther200316423724012850127

- RodrigoGJRodrigoCTriple inhaled drug protocol for the treatment of acute severe asthmaChest200312361908191512796167

- VirchowJCLommatzchMAnticholinergic agents in asthmaOxfordClinical Publishing2007

- VatrellaAPonticielloAPelaiaGParrellaRCazzolaMBronchodilating effects of salmeterol, theophylline and their combination in patients with moderate to severe asthmaPulm Pharmacol Ther2005182899215649850

- RobertsGNewsomDGomezKIntravenous salbutamol bolus compared with an aminophylline infusion in children with severe asthma: a randomised controlled trialThorax200358430631012668792

- SilvermanRAOsbornHRungeJIV magnesium sulfate in the treatment of acute severe asthma: a multicenter randomized controlled trialChest2002122248949712171821

- BeasleyRAldingtonSMagnesium in the treatment of asthmaCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol20077110711017218820

- MortimerKJTattersfieldAEBenefit versus risk for oral, inhaled, and nasal glucocorticosteroidsImmunol Allergy Clin North Am200525352353916054541

- KeenanGFManagement of complications of glucocorticoid therapyClin Chest Med19971835075209329873

- JosephABrasingtonRKahlLRanganathanPChengTPAtkinsonJImmunologic rheumatic disordersJ Allergy Clin Immunol1252 Suppl 2S204S21520176259

- CometRDomingoCLarrosaMBenefits of low weekly doses of methotrexate in steroid-dependent asthmatic patients. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studyRespir Med2006100341141916099632

- HedmanJSeidemanPAlbertioniFStenius-AarnialaBControlled trial of methotrexate in patients with severe chronic asthmaEur J Clin Pharmacol19964953473498866626

- TriggCJDaviesRJComparison of methotrexate 30 mg per week with placebo in chronic steroid-dependent asthma: a 12-week double-blind, cross-over studyRespir Med19938732112168497701

- MullarkeyMFLammertJKBlumensteinBALong-term methotrexate treatment in corticosteroid-dependent asthmaAnn Intern Med199011285775812327677

- ShinerRJKatzIShulimzonTSilkoffPBenzaraySMethotrexate in steroid-dependent asthma: long-term resultsAllergy19944975655687825725

- DomingoCMorenoAAmengualMJCometRLujanMTwelve years’ experience with methotrexate for GINA treatment step 5 asthma patientsCurr Med Res Opin200925236737419192981

- AaronSDDalesREPhamBManagement of steroid-dependent asthma with methotrexate: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trialsRespir Med1998928105910659893776

- DaviesHOlsonLGibsonPMethotrexate as a steroid sparing agent for asthma in adultsCochrane Database Syst Rev20002CD00039110796540

- MarinMGLow-dose methotrexate spares steroid usage in steroid-dependent asthmatic patients: a meta-analysisChest1997112129339228353

- CorriganCJKayABT cells and eosinophils in the pathogenesis of asthmaImmunol Today199213125015071361126

- FukudaTAsakawaJMotojimaSMakinoSCyclosporine A reduces T lymphocyte activity and improves airway hyperresponsiveness in corticosteroid-dependent chronic severe asthmaAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol199575165727621064

- KhanLNKonOMMacfarlaneAJAttenuation of the allergen-induced late asthmatic reaction by cyclosporin A is associated with inhibition of bronchial eosinophils, interleukin-5, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and eotaxinAm J Respir Crit Care Med20001624 Pt 11377138211029348

- SihraBSKonOMDurhamSRWalkerSBarnesNCKayABEffect of cyclosporin A on the allergen-induced late asthmatic reactionThorax19975254474529176537

- LockSHKayABBarnesNCDouble-blind, placebo-controlled study of cyclosporin A as a corticosteroid-sparing agent in corticosteroid-dependent asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med199615325095148564089

- NizankowskaESojaJPinisGTreatment of steroid-dependent bronchial asthma with cyclosporinEur Respir J199587109110997589392

- AlexanderAGBarnesNCKayABTrial of cyclosporin in corticosteroid-dependent chronic severe asthmaLancet19923987893243281346410

- NizankowskaEDworskiRSzczeklikACyclosporin for a severe case of aspirin-induced asthmaEur Respir J1991433801864356

- SzczeklikANizankowskaEDworskiRDomagalaBPinisGCyclosporin for steroid-dependent asthmaAllergy19914643123151897692

- EvansDJCullinanPGeddesDMCyclosporin as an oral corticosteroid sparing agent in stable asthmaCochrane Database Syst Rev20012CD00299311406057

- DougadosMAwadaHAmorBCyclosporin in rheumatoid arthritis: a double blind, placebo controlled study in 52 patientsAnn Rheum Dis19884721271333281603

- KornbluthAPresentDHLichtigerSHanauerSCyclosporin for severe ulcerative colitis: a user’s guideAm J Gastroenterol1997929142414289317057

- SpectorSLKatzFHFarrRSTroleandromycin: effectiveness in steroid-dependent asthma and bronchitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol1974546367379

- SzeflerSJRoseJQEllisEFSpectorSLGreenAWJuskoWJThe effect of troleandomycin on methylprednisolone eliminationJ Allergy Clin Immunol19806664474516968763

- BlackPNBlasiFJenkinsCRTrial of roxithromycin in subjects with asthma and serological evidence of infection with Chlamydia pneumoniaeAm J Respir Crit Care Med2001164453654111520711

- JohnstonSLBlasiFBlackPNMartinRJFarrellDJNiemanRBThe effect of telithromycin in acute exacerbations of asthmaN Engl J Med2006354151589160016611950

- BallBDHillMRBrennerMSanksRSzeflerSJEffect of low-dose troleandomycin on glucocorticoid pharmacokinetics and airway hyperresponsiveness in severely asthmatic childrenAnn Allergy199065137452195921

- KamadaAKHillMRIkleDNBrennerAMSzeflerSJEfficacy and safety of low-dose troleandomycin therapy in children with severe, steroid-requiring asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol19939148738828473676

- NelsonHSHamilosDLCorselloPRLevesqueNVBuchmeierADBucherBLA double-blind study of troleandomycin and methylprednisolone in asthmatic subjects who require daily corticosteroidsAm Rev Respir Dis199314723984048430965

- GareyKWRubinsteinIGotfriedMHKhanIJVarmaSDanzigerLHLong-term clarithromycin decreases prednisone requirements in elderly patients with prednisone-dependent asthmaChest200011861826182711115481

- GotfriedMHJungRMessickCEffects of Six-Week Clarithromycin Therapy in Corticosteroid-Dependent Asthma: A Randomized Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot StudyCurr Ther Res Clin Exp2004651112

- SimpsonJLPowellHBoyleMJScottRJGibsonPGClarithromycin targets neutrophilic airway inflammation in refractory asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177214815517947611

- Omalizumab for persistent allergic asthmaExcellence NIoCLondonNICE technology appraisal guidance2007133

- GouldHJSuttonBJIgE in allergy and asthma todayNat Rev Immunol20088320521718301424

- PrestaLShieldsRO’ConnellLThe binding site on human immunoglobulin E for its high affinity receptorJ Biol Chem19942694226368263737929356

- ShieldsRLWhetherWRZioncheckKInhibition of allergic reactions with antibodies to IgEInt Arch Allergy Immunol19951071–33083127613156

- BouletLPChapmanKRCoteJInhibitory effects of an anti-IgE antibody E25 on allergen-induced early asthmatic responseAm J Respir Crit Care Med19971556183518409196083

- FahyJVFlemingHEWongHHThe effect of an anti-IgE monoclonal antibody on the early- and late-phase responses to allergen inhalation in asthmatic subjectsAm J Respir Crit Care Med19971556182818349196082

- WalkerSMonteilMPhelanKLassersonTJWaltersEHAnti-IgE for chronic asthma in adults and childrenCochrane Database Syst Rev20062CD00355916625585

- BousquetJCabreraPBerkmanNThe effect of treatment with omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, on asthma exacerbations and emergency medical visits in patients with severe persistent asthmaAllergy200560330230815679714

- BousquetJWenzelSHolgateSLumryWFreemanPFoxHPredicting response to omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, in patients with allergic asthmaChest200412541378138615078749

- ChippsBCorrenJFinnAHedgecockSFoxHBloggMOmalizumab significantly improves quality of life in patients with severe persistent asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol20051152S5S19

- FinnAGrossGvan BavelJOmalizumab improves asthma-related quality of life in patients with severe allergic asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2003111227828412589345

- VignolaAMHumbertMBousquetJEfficacy and tolerability of anti-immunoglobulin E therapy with omalizumab in patients with concomitant allergic asthma and persistent allergic rhinitis: SOLARAllergy200459770971715180757

- CruzAALimaFSarinhoESafety of anti-immunoglobulin E therapy with omalizumab in allergic patients at risk of geohelminth infectionClin Exp Allergy200737219720717250692

- CazzolaMPolosaRAnti-TNF-alpha and Th1 cytokine-directed therapies for the treatment of asthmaCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol200661435016505611

- MorjariaJBBabuKSHolgateSTPolosaRTumour necrosis factor alpha as a therapeutic target in asthmaDrug Discov Today Ther Strateg200633309316

- FeldmannMMainiRfor Lasker Clinical Medical Research AwardTNF defined as a therapeutic target for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseasesNat Med200391245125014520364

- ErinEMLeakerBRNicholsonGCThe effects of a monoclonal antibody directed against tumour necrosis factor-{alpha} (TNF-{alpha}) in asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006

- RouhaniFNMeitinCAKalerMMiskinis-HilligossDStylianouMLevineSJEffect of tumor necrosis factor antagonism on allergen-mediated asthmatic airway inflammationRespir Med20059991175118216085220

- BerryMAHargadonBShelleyMEvidence of a role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in refractory asthmaN Engl J Med2006354769770816481637

- HowarthPHBabuKSArshadHSTumour Necrosis Factor (TNF {alpha}) as a novel therapeutic target in symptomatic corticosteroid-dependent asthmaThorax2005

- MorjariaJBChauhanAJBabuKSPolosaRDaviesDEHolgateSTThe role of a soluble TNF-A receptor fusion protein (Etanercept) in corticosteroid-refractory asthma: a double blind, randomised placebo-controlled trialThorax2008

- WenzelSEBarnesPJBleeckerERA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade in severe persistent asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179754955819136369

- BongartzTSuttonAJSweetingMJBuchanIMattesonELMontoriVAnti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trialsJAMA2006295192275228516705109

- DesaiDBrightlingCCytokine and anti-cytokine therapy in asthma: ready for the clinic?Clin Exp Immunol20091581101919737225

- LeckieMJten BrinkeAKhanJEffects of an interleukin-5 blocking monoclonal antibody on eosinophils, airway hyper-responsiveness, and the late asthmatic responseLancet200035692482144214811191542

- Flood-PagePTMenzies-GowANKayABRobinsonDSEosinophil’s role remains uncertain as anti-interleukin-5 only partially depletes numbers in asthmatic airwayAm J Respir Crit Care Med2003167219920412406833

- Flood-PagePSwensonCFaifermanIA study to evaluate safety and efficacy of mepolizumab in patients with moderate persistent asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176111062107117872493

- KipsJCO’ConnorBJLangleySJEffect of SCH55700, a humanized anti-human interleukin-5 antibody, in severe persistent asthma: a pilot studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2003167121655165912649124

- Flood-PagePMenzies-GowAPhippsSAnti-IL-5 treatment reduces deposition of ECM proteins in the bronchial subepithelial basement membrane of mild atopic asthmaticsJ Clin Invest200311271029103614523040

- HaldarPBrightlingCEHargadonBMepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthmaN Engl J Med20093601097398419264686

- NairPPizzichiniMMKjarsgaardMMepolizumab for prednisone-dependent asthma with sputum eosinophiliaN Engl J Med20093601098599319264687

- AzzawiMJohnstonPWMajumdarSKayABJefferyPKT lymphocytes and activated eosinophils in airway mucosa in fatal asthma and cystic fibrosisAm Rev Respir Dis19921456147714821596021

- ParkCSLeeSMChungSWUhSKimHTKimYHInterleukin-2 and soluble interleukin-2 receptor in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with bronchial asthmaChest199410624004067774310

- KonOMKayABAnti-T cell strategies in asthmaInflamm Res1999481051652310563467

- RobinsonDSBentleyAMHartnellAKayABDurhamSRActivated memory T helper cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with atopic asthma: relation to asthma symptoms, lung function, and bronchial responsivenessThorax199348126328434349

- BusseWWIsraelENelsonHSDaclizumab improves asthma control in patients with moderate to severe persistent asthma: a randomized, controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178101002100818787222

- WoodruffPGDolganovGMFerrandoREHyperplasia of smooth muscle in mild to moderate asthma without changes in cell size or gene expressionAm J Respir Crit Care Med200416991001100614726423

- CarrollNElliotJMortonAJamesAThe structure of large and small airways in nonfatal and fatal asthmaAm Rev Respir Dis199314724054108430966

- DanekCJLombardCMDungworthDLReduction in airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine by the application of RF energy in dogsJ Appl Physiol20049751946195315258133

- MillerJDCoxGVincicLLombardCMLoomasBEDanekCJA prospective feasibility study of bronchial thermoplasty in the human airwayChest200512761999200615947312

- CoxGMillerJDMcWilliamsAFitzgeraldJMLamSBronchial thermoplasty for asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006173996596916456145

- CoxGThomsonNCRubinASAsthma control during the year after bronchial thermoplastyN Engl J Med2007356131327133717392302

- PavordIDCoxGThomsonNCSafety and efficacy of bronchial thermoplasty in symptomatic, severe asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176121185119117901415

- CastroMRubinASLavioletteMEffectiveness and safety of bronchial thermoplasty in the treatment of severe asthma: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med181211612419815809