?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Adolescent low back pain (ALBP) is a common form of adolescent morbidity which remains poorly understood. When attempting a meta-analysis of observational studies into ALBP, in an effort to better understand associated risk factors, it is important that the studies involved are homogenic, particularly in terms of the dependent and independent variables. Our preliminary reading highlighted the potential for lack of homogeneity in descriptors used for ALBP. This review identified 39 studies of ALBP prevalence which fulfilled the inclusion criteria, ie, English language, involving adolescents (aged 10 to 19 years), pain localized to lumbar region, and not involving specific subgroups such as athletes and dancers. Descriptions for ALBP used in the literature were categorized into three categories: general ALBP, chronic/recurrent ALBP, and severe/disabling ALBP. Whilst the comparison of period prevalence rates for each category suggest that the three represent different forms of ALBP, it remains unclear whether they represented different stages on a continuum, or represent separate entities. The optimal period prevalence for ALBP recollection depends on the category of ALBP. For general ALBP the optimal period prevalence appears to be up to 12 months, with average lifetime prevalence rates similar to 1-year prevalence rates, suggesting an influence of memory decay on pain recall.

Keywords:

Introduction

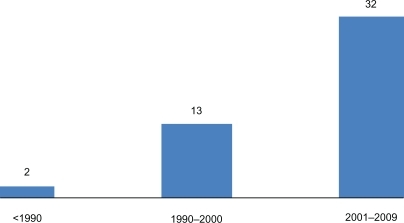

Since the 1980s there has been an increasing appreciation of the extent of adolescent low back pain (ALBP) in the community.Citation1–Citation3 This shift in awareness appears to have resulted from a series of international epidemiological studies which identified a significant prevalence of reported spinal pain in otherwise ‘healthy’ adolescents.Citation4–Citation6

This increased awareness of the prevalence of ALBP is reflected in the increase in published research on ALBP over the past 30 years. For this paper, ALBP refers to low back pain present in adolescents, ie, between 10 and 19 years of age, of no known pathological cause. The published research related to ALBP can be characterized into two major streams. The first stream focuses on the prevalence of ALBP and the associated risk factors, whilst the second stream explores the clinical management of the adolescent presenting with low back pain. This paper focuses on the first of these streams, ie, observational studies which describe the prevalence of ALBP in specific population groups and the associated risk factors.

Despite an increasing number of observational studies into this common form of adolescent morbidity and associated factors, there remains little agreement on the risk factors.Citation7,Citation8 When presented with a number of observational studies, focused on the one condition, meta-analysis has been promoted as the best approach for combining the datasets.Citation9 However, valid meta-analysis depends on homogeneity of the included studies. When significant inter-study differences in methodologies exist, this hinders the ability to amalgamate datasets for analytical purposes.

Defining ALBP

Our preliminary reading highlighted the potential for a lack of homogeneity in the descriptors of ALBP. This paper reviews the definitions used in the literature related to ALBP prevalence. By describing the current situation in terms of the definitions of ALBP used, the foundation is set for further research in identifying a common classification system for use in ALBP. The terms used to present the details of research, in particular dependant variables such as ALBP, are important as they facilitate communication and common understanding.Citation10 To further highlight the effect of definitional differences on ALBP prevalence, the studies identified in this review were categorized into three broad subgroups, according to their definitions, and the relative prevalence of ALBP between these groups was compared using period prevalence rates.

Significant progress has been made in international recognition and understanding of ALBP, but two issues remain. The first issue, common to adult research, is the difficulty in arriving at an agreed diagnosis for the LBP.Citation11 The complexity of the spine, both anatomically and functionally, makes effective diagnosis difficult. Current clinical, surgical, and radiographic investigatory techniques are hampered as the pain-sensitive structures are often not amenable to direct anatomical scrutiny.Citation11 Although there are well-reported descriptions of a range of clinical presentations, an understanding of pain itself, in terms of etiology and pain mechanisms, is less well developed.Citation12

In the adult population, over 50% of LBP sufferers have an unclear diagnosis, despite extensive laboratory and radiographic investigations.Citation13 In nine out of 10 cases, adult spinal pain has been described as transient, related to posture or strain, with recovery occurring in a short period of time.Citation14 Amongst the adult population, 60% to 80% will suffer an episode of LBP in their lifetime with a subset of 2% to 7% reporting ongoing chronic, recurrent pain.Citation15

The second issue, related to etiology, is the range of potentially interdependent and time-dependent factors that influence the reporting of ALBP. These factors, which may present as risk factors or prognostic factors, affect the development and progression of the condition. The wide variation in timing and tempo of the developmental processes within an adolescent population further compounds the difficulty in identifying and categorizing these factors. Epidemiological studies play an important role in providing information on the etiology, natural history, impact of health conditions such as ALBP, and the interrelationships between potential risk and prognostic factors.Citation16

These two issues are intrinsically linked to progressing the understanding of ALBP. The ability to identify causes of ALBP is dependent on the ability to accurately define and classify ALBP. It is naïve to consider that all forms of self-reported ALBP are the same and, likewise, optimistic to consider that all types of ALBP are caused by the same factors.

Observational studies into the prevalence of ALBP have generally avoided identifying a pathoanatomical cause for the pain. The etiology for the ALBP reported in these studies remains unknown, with the range of potential causes outlined in .

Table 1 Potential causes for ALBP

When attempting to understand the prevalence and the behavior of potential risk factors for a condition such as ALBP through observational studies, the first step is to classify the subjects who have the condition. In some conditions this classification process is self explanatory, often through the presence of a measurable biological marker, whilst in other conditions, such as ALBP, it is harder to define.

The measure most commonly collected is an adolescent’s self-report of pain. However, self-reported pain can be described in multidimensional terms, using measures such as chronicity, frequency, episode duration,Citation19 intensity (ie, pain effects), severity (including effect on activities of daily living [ADL]),Citation16,Citation20 and recall prevalence. These measures are not mutually exclusive, with each describing an aspect of the pain experience. However, of these measures, recall prevalence is the most stable across the studies as the comparative scale (ie, period of recall) is standardized.

Recall prevalence is described in terms of the period of recall required:

– 1-week prevalence is the proportion of the population who experienced symptoms over the week preceding the questioning.

– 1-month prevalence is the proportion of the population who experienced symptoms over the month preceding the questioning.

– 1-year prevalence is the proportion of the population who experienced symptoms over the 12 months preceding the questioning.

– Lifetime prevalence is the portion of the population who experienced symptoms at any stage of their life preceding the questioning.

Whilst point prevalence refers to pain at the time of the assessment, some authors have taken a broader view and include 1-week prevalence data within their definition of point prevalence.Citation21

The ability of subjects to accurately report on their pain prevalence over any of these periods will depend on their ability to recall the pain.Citation19 A number of factors may influence the optimal period over which to collect data in determining the prevalence of ALBP in a community.

Memory decay is a term used to describe the gradual memory loss that occurs over time when recalling significant events.Citation22 Three factors determine the extent to which memory decay will affect the data collected on ALBP prevalence: (a) the longer the time period of recall the greater the potential influence of memory decay, (b) the more significant the incident the less likely that memory decay will occur, and (c) the innate ability of the individual to recall events will influence the rate of memory decay.

Forward telescoping describes the tendency for a subject to recollect events, such as LBP, as occurring more recently than they actually did.Citation22 An example would be an adolescent who had an episode of LBP two years ago, but who includes it within 1-year prevalence data. This will tend to increase the reported prevalence of LBP when investigating period prevalence, particularly over shorter time periods.

The shortest period of recall is pain at the time of data collection, ie, point prevalence. However, too short a period of recall may limit the ability to collect data from sufficient subjects to develop an understanding of the risk factors associated with ALBP. This is counterbalanced by the notion that collection of data on ALBP reported at the time of questionnaire delivery will significantly reduce the potential for memory decay to affect the data validity.

The longest period of recall is lifetime prevalence, where the subject is asked if they have had any episode of LBP. The use of lifetime prevalence will negate the influence of forward telescoping, however memory decay presents a significant influence.

It remains unclear what is the most valid or reliable period prevalence to use for the collection of ALBP prevalence rates, however, due to the stable nature of recall prevalence definition across the literature, this measure will be used in this review to compare the potential effect of differing ALBP definitions on prevalence rates.

Material and methods

Literature search

The electronic databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL were searched using the Medical Subject Headings: Adolescent, Low Back, Pain, and the keywords: adolescent, children, low back pain, spinal pain, lumbar pain. Bibliographies of relevant articles were manually searched. No age restrictions were applied to the search strategy.

Inclusion criteria

No attempt was made to exclude studies based on study quality. Articles were included if they were in English language and available in full text. Studies were excluded if they did not specifically describe the low back area, did not focus on adolescents (aged between 10 and 19 years), were focused on specific causes of ALBP (ie, related to backpack carriage), or related to specific adolescent subpopulations (ie, athletes).

Analysis

All articles were reviewed for the description of ALBP used. This definition was either stated directly in the paper or was extrapolated from the questions used to collect ALBP data. The definitions were then collated and characterized into three groups, based on their defining characteristics:

General ALBP: any ALBP, ie, there were no restrictions placed on the reported ALBP.

Chronic/recurrent ALBP: low back pain that was characterized by a measure of chronicity or recurrence.

Severe/disabling ALBP: low back pain that was characterized by a measure of severity, ie, effect on activity.

ALBP prevalencedata from each study by recall prevalence was recorded in an Excel© (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet for further analysis.

Results

Article selection

The initial literature search yielded 89 citations. These articles were screened for relevance and content. Of those, 42 did not meet eligibility criteria, leaving 47 articles which underwent detailed review. The main reasons for failing to meet eligibility criteria was a failure to define the area of the low back, a focus on specific subgroups of adolescents (athletes, dancers), and failure to specifically present prevalence rates for subjects between the ages 10 to 19 years of age. Of the 47 articles selected three involved re-analysis of data presented in a previous study, and were therefore not included in the prevalence review. and present the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2 Characteristics of the studies presenting ALBP prevalence data used in this review

Due to the small number of subjects that presented ALBP prevalence data once broken down by gender and chronological age, the data for average prevalence for both male and female over the recall periods were used in this review.

presents the definitions for ALBP used in the studies identified in this review, and the subsequent groupings of the ALBP type based on the definition used.

Table 3 Characteristics of the studies presenting ALBP prevalence data used in this review

presents the prevalence rates reported in the studies, by period prevalence and ALBP category. These prevalence rates are summarized in .

Table 4 Period prevalence rates for each category of ALBP

Table 5 Summary of period prevalence rates for each category of adolescent low back pain

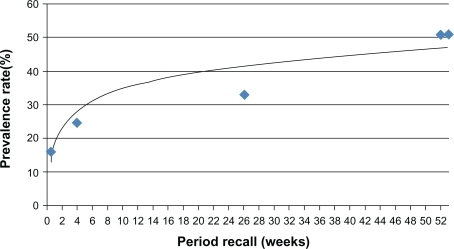

General ALBP was the most common definition of ALBP from the literature reviewed, and therefore presented the most data for each period prevalence. The 1-week, 1-month, and 1-year prevalence rates for this category of ALBP were graphed against a 12-month timeline, and a logarithmic trend line applied to these points. As the relationship between period prevalence rates was not expected to be linear, ie, a ‘ceiling effect’ was expected over an extended period, a logarithmic trend line was used to describe the relationship between period prevalence rates over the 12-month period.

The logarithmic trend line for general ALBP over the 12-month period and the corresponding correlation coefficient is presented below (where y = prevalence rate (%), and x = weeks).

Discussion

This review identified that within the literature related to the prevalence of low back pain amongst adolescents, there were a range of definitions used. When these definitions were classified into three broad categories they represented different prevalence rates.

The particular concern identified by this study was that most papers reported their adolescent subjects as suffering low back pain, without consideration of the definitional parameters. This constrains the ability to synthesize the literature to identify risk factors, as studies with different pain definitions (in terms of severity, chronicity, and intensity) lack homogeneity, as they are describing different pain situations.Citation16 Within each of the three broad classifications used in this review, there were significant differences in the period prevalence rates across studies, suggesting a wide variation in ALBP prevalence rates.

The logarithmic trend line calculated in this paper represents the behavior of the average ALBP prevalence rate for each period recall from the literature available. As more studies are published, which present prevalence data for each category of ALBP, the robustness of this formula should improve. This trend line can be seen to represent the ‘natural’ history of ALBP within a normal adolescent population. As the robustness of this formula improves, it presents a unique measure to review the success of any intervention aiming to reduce the prevalence of ALBP.

Whilst all of these studies reported on the prevalence of ALBP, the differing definitions used mean that they may be referring to different forms of ALBP. When attempting to identify risk factors it seems prudent to ensure that the form of ALBP is the same across the population studied. When collating and analyzing evidence from the literature, it is important to compare “apples with apples, and oranges with oranges.” In the situation described in this paper, it is not certain that this is currently the case with ALBP.

It remains unclear whether the different definitions refer to different forms of ALBP, or to different points along a continuum of one form of ALBP. Whilst general ALBP reflects any low back pain, chronic/recurrent ALBP and severe/disabling ALBP represents pain of a specific form.

Five examples of question wording are provided below:

Any ache, pain, or discomfort in the lower back

Any pain in the low back

Low back pain lasting for one day or longer

Pain in the low back at least weekly

Low back pain that that interfered with school, work, or leisure activities.

These five different definitions would seem to refer to different types of ALBP.

Whilst some studies have attempted to define ALBP in terms of chronicity, severity, frequency, or episode duration, they have often failed to provide a well defined set of parameters for each measure. For example, chronicity is widely used in both the adult and adolescent LBP research literature, however it remains a poorly defined term that lacks consensus.Citation20 Chronicity can be viewed on a continuum, from an always present condition at one end through to a condition that recurs regularly at the other. Diepenmaat et alCitation28 defined ALBP as greater than four days per month of pain, and ignored any report of ALBP less than three days ALBP per month. In the Mikkelson et alCitation61 definition, for a person to be considered to have ALBP they must have had it for at least once a week over the previous three months. Failure to report weekly pain over a three month period classified the subject as having no pain.

Feldman et alCitation31 used a definition of ALBP as low back pain reported by adolescents which occurred at least once a week for six months. Anything less than this was deemed to be ‘transient, inconsequential’ pain. Alternatively, Hakala et alCitation34 included those subjects reporting monthly low back pain in the previous six months in the group without ALBP. Statements such as, “It is probable that a single attack of mild LBP once a year has no particular significance for one’s health status,”Citation33 remain unsubstantiated.

None of the studies, which classified ALBP according to chronicity, severity, or frequency, provided any justification for these classifications. Whilst all of the studies reviewed described their adolescent subjects as having low back pain, it would facilitate discussions if the description included consideration of the category of ALBP. indicates that over the period prevalence rates the reported rate of chronic/recurrent or severe/disabling ALBP (ie, where a definition involved a criterion of recurrences or effects on activities of daily living) were lower than that for the general ALBP.

The period over which the subjects have been asked to recall any episodes of ALBP also varied significantly between studies.

In this review, there was little difference between the average lifetime prevalence (53%) and the 1-year prevalence (53.9%) of general ALBP. The longer the duration of recall the greater the potential for forgetfulness with extensive periods potentially providing unreliable data.Citation16 It is more likely in lifetime prevalence data that the results are more reflective of significant episodes, rather than less limiting or less severe episodes.

Burton et alCitation26 found a high level of forgetfulness of previous LBP (1-year prevalence) in a group of 216 schoolchildren studied over the five years of their secondary schooling. Almost 60% of the students who reported LBP forgot at least one previous episode of spinal pain during annual questioning. This study suggested that with the use of a 1-year recall period, the influence of memory decay may significantly affect the accuracy of the prevalence data.

The effect of memory decay on the lifetime prevalence rate appears less significant for chronic/recurrent or severe/disabling ALBP. This difference between general ALBP and the other two categories may reflect the influence of a ‘saliency rule’, where more significant episodes are remembered more than less significant events.

Conclusion

This review of the ALBP prevalence literature identified a range of definitions used to define low back pain in adolescents.

The review of the ALBP prevalence data identified that the prevalence rates differed between three categories of ALBP definitions, ie, general ALBP, chronic/recurrent ALBP, and severe/disabling ALBP. It remains unclear how the three categories are related. Each category of ALBP may have different risk factors, which require further investigation.

For all types of ALBP, there appears to be a steady increase in average prevalence rates with the passing of time. For general ALBP this represented a relationship over 12 months represented by the equation y = 7.274 ln(x) + 17.68 R2 = 0.792 (where y = prevalence rate (%), and x = weeks).

There did not appear to be significant difference between lifetime prevalence and 12-month prevalence in general ALBP, however for severe/disabling and chronic/recurrent ALBP a greater variation between the two prevalence rates was identified, potentially reflecting the effect of a saliency rule.

Differences in prevalence rates between the three categories of ALBP used in this review suggests that definitions of ALBP need to be standardized across studies, particularly in the search for risk factors. This will promote better homogeneity of studies into ALBP, allowing a stronger meta-analysis of the observational studies, and a better understanding of this condition.

Consideration of a classification system for ALBP will facilitate communication between the epidemiological and the clinical streams of ALBP research.

The most consistent reporting of ALBP appears to be for general ALBP, reported in period prevalence rates of 12 months or less.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ViryPCreveuilCMarcelliCNonspecific back pain in childrenRevue du Rhumatisme (English Edition)1999667–9381388

- TaimelaSKujalaUMSalminenJJViljanenTThe prevalence of low back pain among children and adolescents: a nationwide, cohort based questionnaire survey in FinlandSpine19972210113211369160472

- McMeekenJTullyEStillmanBNattrassCBygottIStoryIThe experience of back pain in young AustraliansManual Therapy200164421322011673931

- BalagueFDutoitGWaldburgerMLow back pain in schoolchildrenScand J Rehabil Med1988201751792976526

- TurnerPGGreenJHGalaskoCSBBack pain in childhoodSpine19891488128142528813

- HertzbergAPrediction of cervical and low-back pain based on routine school health examinations: a nine-to-twelve-year follow-up studyScand J Prim Health Care1985342472532934780

- BalagueFTroussierBSalminenJJNon-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factorsEur Spine J1999842943810664299

- LeggSJTrevelyanFCCarpentierMPFuchsBSpinal musculoskeletal discomfort in New Zealand intermediate schoolsIEA 2003: Proceedings of the 15th Congress of the International Ergonomics Association, Ergonomics for Children in Educational Environments Symposium2003 Aug 24–29Seoul, Korea

- BlettnerMSaueerbreiWSchlehoferBScheuchenpflugTFriedenreichCTraditional reviews, meta-analyses and pooled analyses in epidemiology. InternationalJ Clin Epidemiol19992819

- JensenTSGebhart GF. New pain terminology: a work in progressPain200814039940019004550

- GilesLGFTaylorJRLow back pain associated with leg length inequalitySpine1981555105216458101

- GroholtEKStigumHNordhagenRKohlerLRecurrent pain in children, socioeconomic factors, and accumulation in familiesEur J Epidemiol20031896597514598927

- FrymoyerJWPopeMHClementsJHWilderDGMacPhersonBAshikagaTRisk factors in low back pain: an epidemiological surveyJ Bone Joint Surg Am19836522132186218171

- DixonASSoft tissue rheumatism: concept and classificationClinics in Rheumatic Diseases197953739742

- KoesBWvan TulderMWThomasSDiagnosis and treatment of low back painBMJ20063321430143416777886

- GoodmanJEMcGrathPJThe epidemiology of pain in children and adolescents: a reviewPain1991462472641758709

- BalagueFNordinMBack pain in children and teenagersBailliere’s Clin Rheumatol199263575593

- KingHAEvaluating the child with back painPediatric Clinics of North America1986336148914932947036

- EbrallPSThe epidemiology of male adolescent low back pain in a north suburban population of Melbourne, AustraliaJ Manipulative Physiol Ther19941774474537989878

- HaefeliMElferingAPain assessmentEur Spine J200614S17S2416320034

- BalagueFDamidotPNordinMParnianpourMWaldburgerMCross sectional study of the isokinetic muscle trunks strength among school childrenSpine1993189119912058362327

- VolinnEThe epidemiology of low back pain in the rest of the world: a review of surveys in low and middle income countriesSpine19972215174717549259786

- AuvinenJTammelinTTaimelaSZittingPKarppinenJAssociations of physical activity and inactivity with low back pain in adolescentsScand J Med Sci Sports20081818819417490453

- BalagueFNordinMSkovronMLDutoitGYeeAWaldburgerMNon-specific low back pain among school children: a field survey with analysis of some associated factorsJ Spinal Disord1994753743797819636

- BalagueFSkovronMLNordinMDutoitGPolLRWaldburgerMLow back pain in school children: a study of familial and psychological factorsSpine19952011126512707660235

- BurtonKAClarkeRDMcCluneTDTillotsonMKThe natural history of low back pain in adolescentsSpine19962120232323288915066

- CakmakAYuceiBOzyalcinSThe frequency and associated factors of low back pain among a younger population in TurkeySpine200429141567157215247580

- DiepenmaatACMvan der WalMFde VetHCWHirasingRANeck/shoulder, low back, and arm pain in relation to computer use, physical activity, stress, and depression among Dutch adolescentsPediatrics200611741241616452360

- El-MetwallyAMikkelssonMStahMGenetic and environmental influences on non-specific low back pain in children: a twin studyEur Spine J20081750250818205017

- FeldmanDERossignolMShrierIAbenhaimLSmoking: a risk factor for development of low back pain in adolescentsSpine199924232492249610626312

- FeldmanDEShrierIRossignolMAbenhaimLRisk factors for the development of low back pain in adolescenceAm J Epidemiol20011541303611427402

- GrimmerKWilliamsMGender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back painAppl Ergon20003134336010975661

- HarrebyMNygaardBJessenTRisk factors for low back pain in a cohort of 1,389 Danish school children: an epidemiological studyEur Spine J1999844445010664301

- HakalaPRimpelaASalminenJJVirtanenSMRimpelaMBack, neck, and shoulder pain in Finnish adolescents: national cross sectional surveysBMJ2002325473476

- JonesGTWatsonKDSilmanAJSymmonsDPMMacfarlaneGJPredictors of low back pain in British schoolchildren: a population-based prospective cohort studyPediatrics2003111482282812671119

- BejiaIAbidNSalemKBLow back pain in a cohort of 622 Tunisian schoolchildren and adolescents: an epidemiological studyEur Spine J20051433133615940479

- JonesMAStrattonGReillyTUnnithanVBA school-based survey of recurrent non-specific low back pain prevalence and consequences in childrenHealth Educ Res2004a19328428915140848

- JonesGTSilmanAJMacfarlaneGJParental pain is not associated with pain in the child: a population based studyAnn Rheum Dis2004b631152115415308526

- KjaerPLeboeuf-YdeCSorensenJSBendixTAn epidemiologic study of MRI and low back pain in 13-year old childrenSpine200530779880615803084

- KristensenCBoKOmmundsenYLevel of physical activity and low back pain in randomly selected 15 year-olds in Oslo, Norway – an epidemiological study based on surveyAdv Physiother200138691

- KujalaUMTaimelaSViljanenTLeisure physical activity and various pain symptoms among adolescentsBr J Sports Med1999b3332532810522634

- MasieroSCarraroECeliaASartoDErmaniMPrevalence of non-specific low back pain in schoolchildren aged between 13 and 15 yearsActa Paediatrica20089721221618177442

- MierauDCassidyJDYong-HingKLow back pain and straight leg raising in children and adolescentsSpine19891455265282524892

- MogensenAMGauselAMWedderkopNKjaerPLeboeuf-YdeCIs active participation in specific sport activities linked with back pain?Scand J Soc Med200717680686

- MurphySBucklePStubbsDA cross-sectional study of self reported back and neck pain among English schoolchildren and associated physical and psychological risk factorsAppl Ergon20073879780417181995

- MurphySBucklePStubbsDBack pain amongst school children and associated risk factorsIEA 2003: Proceedings of the 15th Triennial Congress of the International Ergonomics Association, Ergonomics for Children in Educational Environments Symposium2003 Aug 24–29Seoul, Korea

- OlsenTLAndersonRLDearwaterSRThe epidemiology of low back pain in an adolescent populationAm J Public Health19928246066081532116

- PrendevilleKDockrellSA pilot survey to investigate the incidence of low back pain in school childrenPhysiotherapy Ireland199819137

- PristaABalagueFNordinMSkovronMLLow back pain in Mozambican adolescentsEur Spine J20041334134515034774

- KovacsFMGestosoMGil del RealMTLopezJMufraggiNMendezJIRisk factors for non-specific low back pain in schoolchildren and their parents: a population based studyPain200310325926812791432

- ShehabDAl-JarallahKAl-GhareebFSanaseeriSAl-FadhiMHabeebSIs low back pain prevalent among Kuwaiti children and adolescents?Med Princ Pract20041314214615073426

- SjolieANPsychosocial correlates of low back pain in adolescentsEur Spine J20021158258812522717

- SjolieANLow back pain in adolescents is associated with poor hip mobility and high body mass indexScand J Med Sci Sports20041416817515144357

- SkofferBFoldspangAPhysical activity and low back pain in schoolchildrenEur Spine J20081737337918180961

- StaesFStappaertsKLesafreEVertommenHLow back pain in Flemish adolescents and the role of perceived social support and effect on the perception of back painActa Paediatrica20039244445112801111

- TroussierBMarchou-LopezSPironneauSBack pain and spinal alignment abnormalities in schoolchildrenRevue du Rhumatisme (English Edition)1999667–9370380

- VikatARimpelaMSalminenJJRimpelaASavolainenAVirtanenSMNeck or shoulder pain and low back pain in Finnish adolescentsScand J Public Health20002816417311045747

- WatsonKDPapageorgiouACJonesGTLow back pain in schoolchildren: the role of mechanical and psychosocial factorsAm J Dis Child2003881217

- WatsonKDPapageorgiouACJonesGTLow back pain in schoolchildren: occurrence and characteristicsPain200297879212031782

- WedderkopNLeboeuf-YdeCAndersenLBFrobergKHansenHSBack pain reporting pattern in a Danish population based sample of children and adolescentsSpine200126171879188311568698

- MikkelsonMSalimenJJKautiainenHNonspecific musculoskeletal pain in preadolescents. Prevalence and 1-year persistencePain19977329359414054

- Mohseni-BandpeiMABagheri-NesamiMShayesteh-AzarMNonspecific low back pain in 5,000 Iranian school-age childrenJ Pediatr Orthop200727212612917314634

- Van GentCDolsJJCMde RoverCMSingRAHde VetHCWThe weight of schoolbags and the occurrence of neck, shoulder, and back pain in young adolescentsSpine200328991692112942008