Abstract

In clinical practice, a growing need exists for effective non-pharmacological treatments of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Here, we present the results of a pilot study of 10 adults with ADHD participating in short-term individual cognitive- behavioral therapy (CBT), 9 adults participating in cognitive training (CT), and 10 controls. Self-report questionnaires, independent evaluations, and computerized neurocognitive testing were collected before and after the treatments to evaluate change. There were distinctive pre-hypotheses regarding the treatments, and therefore the statistical comparisons were conducted in pairs: CBT vs control, CT vs control, and CBT vs CT. In a combined ADHD symptom score based on self-reports, 6 participants in CBT, 2 in CT and 2 controls improved. Using independent evaluations, improvement was found in 7 of the CBT participants, 2 of CT participants and 3 controls. There was no treatment-related improvement in cognitive performance. Thus, in the CBT group, some encouraging improvement was seen, although not as clearly as in previous research with longer interventions. In the CT group, there was improvement in the trained tasks but no generalization of the improvement to the tasks of the neurocognitive testing, the self- report questionnaires, or the independent evaluations. These preliminary results warrant further studies with more participants and with more elaborate cognitive testing.

Introduction

The management of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been under increasing scientific and public debate in recent years, and the need for effective treatments is widely recognized. The most extensively studied treatments are pharmacological (for reviews, see, Dopheide & PliszkaCitation1 and Tcheremissine et alCitation2). Pharmacotherapy is thought to help with attention and executive functions deficits, but does not help the individual to develop compensatory strategies. Therefore, in the last 10 years studies on psychological interventions have also emerged. Several group interventionsCitation3–Citation9 have yielded promising results in treating adults with ADHD. Only a few studies on individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have been published.Citation10–Citation12 Wilens et alCitation10 reported the effectiveness of 10–103 sessions of individual cognitive therapy, but there was no control group and the study was conducted as a chart review. Safren et alCitation12 randomized their participants to continued pharmacotherapy alone or a combined pharmacotherapy plus a CBT treatment that they had developed. The combined treatment was found to be associated with better improvement in self-reported symptoms and independent evaluators’ ratings as compared to pharmacotherapy alone. Rostain and RamsayCitation11 combined pharmacotherapy with 16 sessions in a period of six months of CBT modified to treat adults with ADHD, but they had no control group. They found that the treatment was associated with improvements in the measures used, but as they state, their study design did not allow conclusions about the relative contribution of CBT or pharmacotherapy.

Psychosocial treatments usually focus on compensatory strategies, altering dysfunctional thoughts and attitudes, and improving metacognition, but they do not directly target the core cognitive symptoms of ADHD, such as problems of attention or working memory. In children, some results have been reported on the effectiveness of cognitive training (CT) in treating these deficits.Citation13–Citation16 These studies are, however, only case reports or include a small number of patients. There is some evidence that healthy adults may also benefit from computerized working memory training.Citation13,Citation17 In adults with ADHD, attention-switching impairment has been shown to ameliorate with short-term computerized training.Citation18 To the best of our knowledge, no other studies on CT in adults with ADHD have been reported before.

The aim of this study was to preliminary examine the feasibility and efficacy of short-term individual CBT and CT in adults with ADHD and their impact on ADHD symptoms, mood, quality of life, and cognitive performance. We hypothesized that (i) compared to the controls, the participants in the CBT group would benefit from the treatment, although this may not be as clear as in previously published studies because of the shorter duration of the therapy, and (ii) the participants in the CT group would improve their performance in trained tasks, and this improvement would at least partly generalize to other measures of the same cognitive functions. In addition, we hypothesized that the participants in the CT group would benefit from the treatment as compared to the control group, and this is seen partly in their cognitive performance but not as clearly in their self-reports. Although children with ADHD have been shown to benefit from CT, the adult brain has less plasticity, and thus the treatment gain is hypothesized to be smaller in adults, and (iii) the participants in CBT would benefit more than the participants in CT.

Method

Participants

The participants were recruited by announcements placed in an ADHD magazine and an adult ADHD internet discussion forum, and by informing local physicians and clinics specialized in treating ADHD in adults. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) 18–49 years of age; (ii) ADHD diagnosis made by a physician; (iii) no diagnosis of psychosis, severe depression or paranoia; (iv) deficits of attention, executive functions or working memory identified in a neuropsychological evaluation that had been made earlier; (v) no current alcohol dependency or drug use; (vi) not receiving a disability pension; (vii) no participation in our previous group rehabilitation study; (viii) currently not undergoing any other psychological rehabilitation; and (ix) no medication or medication that has been stable for at least three months.

In total, 71 interested candidates contacted the researchers and were briefly telephone-screened for the inclusion criteria. Of these, 17 individuals were excluded for not meeting all the inclusion criteria: 11 for having no neuropsychological examination and six for reasons such as diagnosis of psychosis, severe depression or paranoia, older age, retired, or current psychological rehabilitation. If the medication was not stabilized, the candidate was put on a waiting list until this criterion was met.

A total of 54 potential candidates were invited to an interview with a psychologist. The aim of the interview was to screen for the inclusion criteria more closely, to explain the study protocol in more detail and to obtain the informed consent of each candidate before recruitment. Medical records were evaluated to ensure the diagnosis of ADHD and the accurate fulfillment of inclusion criteria 3 and 4. Seven candidates withdrew from the study before the interview or did not attend the interview. At the end of the interview, the candidates filled in a questionnaire of detailed background information and the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS).Citation19 On the basis of the collected information, the psychologists (AS, MV) verified that the candidate met both the DSM IV criteria for ADHDCitation20 and the criteria for the study. Only one candidate was excluded at this stage because the required neuropsychological deficits were lacking. Thus there were 46 participants who were randomly assigned to one of four groups: hypnotherapy, individual CBT, computerized CT, or the control group. Four of participants accepted for the study withdrew their participation and three quit during the study (two in the CBT and one in the CT group). Thus there were a total of 39 participants. Here we present the results for the CBT, CT and control groups; the results of the hypnotherapy group are published elsewhere.Citation21

There were 10 participants in the CBT and control groups, and nine in the CT group. The demographic data of the groups are presented in . Five of the 10 participants of the CBT group were receiving medication for ADHD, and all of them took methylphenidate. One participant ceased taking her medication during the rehabilitation, and one added a short-acting methylphenidate Ritalin to the previous long-acting methylphenidate Concerta. Five of the nine participants of the CT group were receiving medication for ADHD: four of them took methylphenidate and one modafinil. One participant ceased taking her methylphenidate medication and one changed from Concerta to Equasym, which is a methylphenidate with shorter duration, during the rehabilitation. Seven of the 10 participants of the control group received medication for ADHD: five took methylphenidate, one received modafinil, and one received atomoxetine (which was changed to methylphenidate during the study).

Table 1 Characteristics of the participants at the beginning of the treatment

The three groups did not differ, as analyzed by an analysis of variance or Chi-Square test, in age, gender, education, work status, WURS score, severity of ADHD (measured by Clinical Global Impressions, CGI at the baseline) or number of participants having psychiatric comorbidity (all Ps > 0.05).

None of the participants in the control group received any treatment during the follow-up period. After the follow-up period, eight of them participated in group rehabilitationCitation7 and the remaining two in individual rehabilitation.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Helsinki University Central Hospital, Finland and performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave their written informed consent prior to participating in the study. Participation was free of charge.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

The themes of the treatment sessions were selected to cover the main symptoms set out in the DSM-IV diagnostic criteriaCitation20 and by Brown.Citation22,Citation23

The CBT consisted of 10 weekly sessions led by a psychologist experienced in ADHD and training in CBT (AS). The themes and contents of the sessions are presented in . The first six sessions and the last session had same content for all the participants, although allowing for some individual modification. Sessions seven, eight and nine were individually tailored. A limit was set at two sessions per theme. For example, it was possible to have self-esteem (session six) as one of the individually chosen sessions or impulsivity (not in sessions one to six) in two individual sessions. The psychologist followed a written manual.Citation24 The sessions were semi-structured so as to allow individual treatment. The most important points and tasks at hand were illustrated using printed material and a whiteboard, and at the end of the session, the material discussed was distributed to the participants in written form. In addition, the participants were given homework related to the theme discussed. Each session followed the same procedure: discussion of the previous homework and theme, introduction and discussion of the new theme, and assignment of the new homework and distribution of the written material. The duration of a session was approximately 60 minutes.

Table 2 Content of the semi-structured cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

Cognitive training

A CT program was developed to include the training of attention, executive functions, and working memory as widely as possible within one hour of computerized, systematic training. The tasks are presented in . The tasks involved domains of attention as follows: focus- executive (tasks 2 and 7), sustain (1A-D, 4A), encode (5), and shift (6),Citation25 and focused (all tasks), sustained (1A-D, 2, 3, 4A-B, 5, 9), selective (1E), alternating (6), and divided (4C, 7, 8) attention.Citation26,Citation27 Some of the tasks required executive functions (task 1E: response inhibition; Tasks 4C and 6: cognitive flexibility) and working memory (3, 5, 9).

Table 3 Content of the cognitive training (CT)

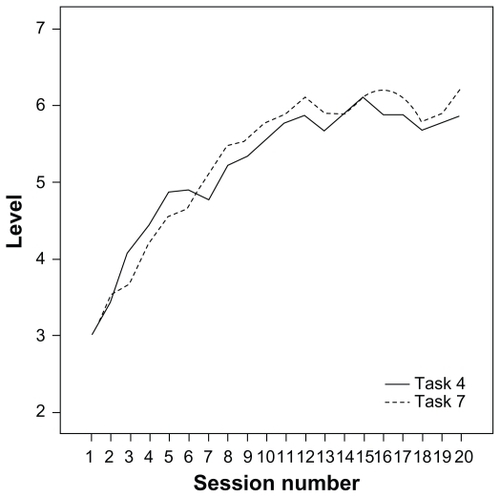

The CT consisted of 20 sessions taking place twice a week and led by a psychologist (AS). Tasks 1A, B and C were practiced only in every third session. All the other tasks were completed in every session. Each participant received feedback on the screen immediately after each task, and the feedback was discussed with the psychologist. There were several difficulty levels in the tasks – at least three in each, and in most of the tasks at least six – and the tasks were adjusted to a suitable level on a trial-by-trial basis (). The duration of a session was approximately 60 minutes.

Because of the large number of tasks and variables, the participants’ performance change is only presented for four tasks in the Results section, namely for tasks 3, 5, 4C and 7. In tasks 3 and 5, the length of the longest correctly remembered/arranged sequence in every session is taken as the result. In tasks 4 and 7, the difficulty level used at each session is the result. In task 7, there were seven difficulty levels in which the visual stimuli were always similar, but the presentation rate of the auditory stimuli varied – that is, the time elapsed from the onset of the previous letter to the onset of the next letter was either 2200, 1900, 1600, 1300, 1100, 900 or 850 ms. At the first session, all the participants started at level three (1600 ms). If the participant’s responses were more than 90% correct and he or she made less than five erroneous responses in both tasks, level four (1300 ms) was presented at the next session. If the participant got less than 70% correct or made more than 10 errors, the easier level two (1900 ms) was presented at the next session. In task 4, the same rules were applied, and the time elapsed from the onset of the previous item to the onset of the next item was 4000, 3500, 3000, 2500, 2000, 1500, 1200, 1100, and 1000 ms (9 levels), starting at level three (3000ms).

Outcome measures

As outcome measures we used self-report questionnaires, independent evaluations, and computerized neurocognitive testing. For the treatment groups, data were collected before the treatment (T1) and after the treatment (T2). Data obtained from the control group were also collected on two occasions. T2 measurements were scheduled to be taken about 11 or 12 weeks after T1 to correspond to the time in the treatment group. The mean time elapsed between T1 and T2 (the questionnaires and the neurocognitive testing) was 82 days (range 63–112) for the CBT group, 94 days (range 56–115) for the CT group, and 81 days (range 69–91) for the control group. The T1 questionnaires and testing were completed 0–12 days before the first CBT or CT sessions, and the T2 measures 0–9 days after the last session. Independent evaluations were collected before T1 and after T2, within two weeks of the collection of self-report questionnaires and neurocognitive testing (with one exception of three weeks). The independent evaluator was a clinical psychologist (MA) who was blind to the actual study group of participants. The measures used were:

Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scale – Adult Version (BADDS)Citation28

The BADDS is a 40-item inventory of which we used the self-report version. From BADDS, a total score and scores of the five subdomains of activation, attention, effort, affect, and memory were derived. Higher scores indicate a greater impairment.

World Health Organization’s Adult ADHD Self-report Scale (ASRS)Citation29

The ASRS is an 18-item scale reflecting the DSM-IV criteria modified for adults. We used both self-report and independent evaluator measurements. We report the total score in which the higher the scores, the greater the impairment.

Symptom Check List (SCL-90)Citation30

The SCL-90 is a 90-item self-report scale for the measurement of psychiatric symptoms. Several subscales can be calculated, but we used the total score. Moreover, a 16-item sum score (SCL-16) reflecting the characteristics prominent in ADHDCitation3 was calculated from the SCL-90. The higher the scores, the greater were the symptoms.

Beck Depression Inventory, second edition (BDI-II)Citation31

The BDI II is a 21-item scale that evaluates current self-reported symptoms of depression. Higher scores reflect greater problems.

Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q)Citation32

The Q-LES-Q is a 93-item self-report scale, from which 91 items can be grouped into eight subscales that indicate satisfaction with physical health, subjective feelings, work, household duties, school, leisure activities, social relationships, and general activities. We combined the work and school subscales into a work/study subscale. When a participant gave both scores, the main score was used (ie, if the participant was working full time and also taking some educational courses, then the work score was used). Higher scores indicate greater enjoyment or satisfaction. The scores are reported as a percentage of the maximum score.

Clinical Global Impressions (CGI)Citation33

CGI was completed by the independent evaluator. At T1, the severity of ADHD was evaluated according to CGI, which is a single 7-point rating scale of functioning varying from 1 = normal, not at all ill, to 7 = among the most extremely ill patients. At T2, global improvement was assessed using a 7-point scale varying from 1 = very much improved, to 7 = very much worse (4 = no change). Classes 1 to 3 were combined to represent improvement, and classes 4 to 7 were combined to represent non-improvement.

CNS Vital Signs (CNSVS)Citation34,Citation35

CNSVS is a computerized neurocognitive test battery comprising seven neuropsychological tests: verbal memory, visual memory, finger tapping, symbol-digit coding, the Stroop test, the shifting attention test, and the continuous performance test. Five standardized domains were obtained from the tests: memory, psychomotor speed, reaction time, cognitive flexibility, and complex attention.

In addition, we used the neurocognition index, which is the mean of the domains. A detailed description of the tests of CNSVS has been given by Gualtieri and Johnson.Citation35,Citation36 In addition, the CBT and CT participants evaluated the benefit of the rehabilitation at T2 using a five-option rating scale of no benefit, minor benefit, moderate benefit, clear benefit, and substantial benefit.

Statistical analyses

The individual missing values on the questionnaires were substituted with the respondent’s mean score. However, no replacements were made in the Q-LES-Q as the scores were calculated as a percentage of the maximum score.

The distribution properties of the variables were inspected visually and with Shapiro-Wilk tests. Parametric tests were chosen for the statistical analyses. Since we had clear prehypotheses to be tested, comparisons were made for three different pairings: the CBT group vs the control group, the CT group vs the control group, and the CBT group vs the CT group. A two-way mixed ANOVA with one between factor, group, and one within factor, time (T1 vs T2) was performed. The effect sizes were quantified by partial eta squared ηp2. When the ANOVA was significant or almost significant (P < 0.10) and the effect size large (ηp2 > 0.138), paired t-tests were also performed for all groups separately. Changes in CGI were analyzed using the Chi-square test (χ2).

Results

The mean scores of the self-report and computerized neurocognitive test battery measures for the CBT, CT and control groups are presented in . The treatment lasted for 10.5 weeks (range 9–15 weeks) for the CBT and 12.2 weeks (range 7.6–15.3 weeks) for the CT.

Table 4 Mean (standard deviation) scores for the participants’ self-ratings and computerized neurocognitive test battery at T1 (before treatment) and T2 (after treatment)

Cognitive behavioral therapy group versus controls

To compare the CBT group with the control group, a two-way ANOVA with one between-factor, group (CBT vs control), and one within-factor, time (T1 vs T2), was performed. There was a significant Time × Group interaction in BADDS attention [F(1,18) = 7.24, P < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.29], memory [F(1,18) = 6.32, P < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.26] and total scores [F(1,18) = 6.32, P < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.26]. Moreover, an almost significant interaction was found for the Q-LES-Q work/study subscale [F(1,11) = 4.28, P = 0.06, ηp2 = 0.28]. As seen in , a decrease in symptoms takes place mainly in participants of the CBT group. No other statistically significant interactions were found in the self-report questionnaires (all Ps > 0.10). There were also no statistically significant interactions in the standardized domains and neurocognition index for CNSVS (all Ps > 0.10).

In the control group, there was no difference between T1 and T2 in any measure (all Ps > 0.05) in paired t-tests. In contrast, there was a significant decrease of symptoms between T1 and T2 in the CBT group in BADDS attention [t(9) = 4.35, P < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.68], memory [t(9) = 2.78, P < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.46] and total scores [t(9) = 3.96, P < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.64].

The participants were classified into two groups according to their individual improvement or nonimprovement during the study. A participant was defined as “improved” when he or she had reduced self-reported symptoms in all ratings of ADHD symptoms, namely the BADDS total score, the SCL-16, and the ASRS. In cases of either symptom elevation or no change in any of the measures, the participant was classified as “not improved”. Six of the 10 participants (60%) in the CBT group were improved compared with two of the ten (20%) in the control group. The difference was almost statistically significant (χ2 = 3.33, df = 1, P = 0.07).

According to the independent evaluators’ CGI ratings, seven of the 10 (70%) participants in the CBT group and three of the 10 individuals (30%) in the control group improved from T1 to T2. The difference was almost statistically significant (χ2 = 3.20, df = 1, P = 0.07). For the independent evaluator-rated ASRS, no statistically significant interaction was found [F(1,18) = 1.67, P = ns, ηp2 = 0.09].

In the participants’ self-evaluations of the treatment benefit, nine of the ten CBT participants reported at least a clear benefit.

Cognitive training group versus controls

The participants’ performance in the trained tasks was analyzed to find out whether there was task-specific improvement related to the rehabilitation. In task 3, the participants were able to remember correctly a sequence of 3.22 (SD 1.48) items in the first session and 5.44 (1.94) in the last session. This difference is statistically significant [t(8) = 4.26, P < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.66]. In task 5, the participants were able to arrange correctly a sequence of 6.56 (SD 1.01) items in the first session and 8.33 (3.40) in the last session, reaching statistical significance [t(8) = 2.16, P < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.44]. The rising learning curve of participants’ performance in tasks 4C and 7 is presented in .

In the self-report questionnaires, when analyzing the CT and control groups with an ANOVA, there was an almost significant Time × Group interaction between T1 and T2 in BADDS affect [F(1,17) = 3.23, P = 0.09, ηp2 = 0.16]. In a paired t-test, the CT group had a significant decrease in symptoms between T1 and T2 [t(8) = 3.18, P < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.56] in BADDS affect (see ). There were no statistically significant interactions in other self-report questionnaires (all Ps > 0.10). No statistically significant interactions were found in measures of CNSVS (all Ps > 0.10).

Two of the nine participants (22%) in the CT group were classified as improved compared with two of the ten (20%) in the control group. Thus, the groups did not differ (χ2 = 0.01, df = 1, P = ns).

According to the independent evaluators’ CGI ratings, two of the nine (22%) participants in the CT group and three of the 10 individuals (30%) in the control group improved from T1 to T2. This difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 0.15, df = 1, P = ns). Moreover, there were no statistically significant interactions for the independent evaluator-rated ASRS [F(1,18) = 0.55, P = ns, ηp2 = 0.03].

In the participants’ self-evaluations of the treatment benefit, four of the nine CT participants reported at least a clear benefit.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus cognitive training

There was an almost significant Time × Group interaction of symptoms between T1 and T2 in BADDS attention [F(1,17) = 3.12, P = 0.09, ηp2 = 0.15] and the SCL-16 [F(1,17) = 4.20, P = 0.06, ηp2 = 0.20], suggesting more improvement in the CBT group (see ). No other statistically significant interactions were found in the self-report measures. Thus, the amelioration of symptoms in the two groups did not statistically differ. No statistically significant interactions were found for CNSVS either (all Ps > 0.10).

As previously mentioned, six of the 10 participants (60%) in the CBT group were classified as improved compared with two of the nine (20%) in the CT group. This difference was almost statistically significant (χ2 = 2.77, df = 1, P = 0.10).

According to the independent evaluators’ CGI ratings, seven of the 10 (70%) participants in the CBT group and two of the nine individuals (22%) in the CT group improved from T1 to T2. This difference was statistically significant (χ2 = 4.34, df = 1, P < 0.05). No statistically significant interaction for the independent evaluator-rated ASRS was found [F(1,17) = 2.52, P = ns, ηp2 = 0.13].

Discussion

The aim of the present pilot study was to examine the potential feasibility and efficacy of short-term CBT and CT in treating adults with ADHD. The influence of the treatments on ADHD symptoms, mood, quality of life, and cognitive performance were evaluated. Both treatments were found to be quite acceptable and tolerable to the participants: only two participants in the CBT group and one in the CT group quit during the rehabilitation. Since there were three distinctive pre-hypotheses, the CBT group was compared to the control group, the CT group to the control group, and the CBT group to the CT group.

Short-term cognitive-behavioral therapy

The self-reported symptoms of participants in the CBT group decreased significantly (or almost significantly with large effect sizes) in BADDS attention, memory, and total scores, and on the Q-LES-Q work/study subscale, as compared to the control group. When individual percentages of change were investigated, six of the 10 participants in the CBT group had improved compared with two of the 10 in the control group. According to the independent evaluator’s CGI ratings, seven of the 10 participants in the CBT group and three of the 10 in the control group, improved from T1 to T2. There were no statistically significant interactions in the standardized domains and neurocognition index of CNSVS. The participants’ self-evaluations regarding the usefulness of the program were quite high; nine of the 10 CBT participants reported at least a clear benefit.

The improvement found in self-report questionnaires, self-evaluations, and independent evaluator’s ratings is consistent with our pre-hypothesis and previous studies of individual CBT in adult ADHD.Citation10–Citation12 It is, nevertheless, somewhat difficult to compare the present and previous studies since they differ in inclusion criteria, study design, and measures used. For example, our participants seemed to benefit less than the participants in Rostain and Ramsay’sCitation11 study, where the BADDS total scores decreased from 70.5 to 49.9 (ours decreased from 84.8 to 71.5). However, their participants received a combined treatment (CBT and medication), whereas the participants of our study were either non-medicated or stably medicated before the treatment. The treatment duration in Rostain and Ramsay’s study was 16 sessions over 6 months as compared to the 10 sessions and 2.5 months of the present study. Since ADHD is a developmental disorder with long-lasting and often pervasive problems, it is reasonable that CBT of longer duration may be needed to develop and establish adaptive coping skills. However, some encouraging improvement was seen with our short-term CBT, although not as clearly as in previous studies with longer interventions. We hypothesize that this kind of short intervention may be useful right after a diagnosis or for milder cases, and longer-term treatments could be used for those with more pervasive problems.

Cognitive training

A training benefit was clearly seen in the trained tasks, where most of the participants improved their performance markedly. However, the benefit was not seen in CNSVS or in most of the self-report questionnaires. Only a decrease in the BADDS affect score was observed (almost statistically significant, large effect size). In addition, no improvement was found in individual percentages of change or independent evaluations.

The improvement in trained tasks is in line with our pre-hypothesis. However, it was also hypothesized that this task-specific improvement would generalize at least in some extent to cognitive measures and perhaps not as strongly to the self-report questionnaires. Against our expectations, this was not found. In a previous study of working memory training with nonmedicated ADHD children, learning was found to generalize to nontrained working memory tasks, other nontrained measures of executive function, and parent ratings, but not to teacher ratings.Citation14 The same study group has also found that working memory training improves performance in healthy adults and that this improvement also transfers to other measures.Citation13,Citation17 Also short-term attention-switching training has been shown to transfer to new tasks of attention-switching in adults with ADHD.Citation18 Thus, our findings also disagree with the previous studies. However, this may not necessarily mean that adults with ADHD do not benefit from this type of CT. It is possible that CNSVS, which was used as the cognitive measure was too easy for the participants (see the general discussion section), or that the CNSVS tasks did not measure the same components of attention and executive functions that were trained. The intensity of training might also be influential. In addition, the improvement seen in BADDS affect is intriguing. This may be just a random result due to the small sample size, or it may reflect the training of impulse control.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the effects of CT in adults with ADHD. Clearly, the possibilities of CT for adult ADHD need to be studied more in the future.

Comparison of the two treatments

The two treatments studied here were equal in length, but differed in intensity: CBT took place once a week, whereas CT took place twice a week. The self-reported symptoms of CBT participants decreased almost significantly more (with a large effect size) in BADDS attention and the SCL-16 as compared to the CT participants. No statistically significant differences were found in CNSVS. According to the individual percentages of change (six of the 10 in the CBT group and two of the nine in the CT group were classified as improved) and the independent evaluators’ CGI ratings (seven of the 10 in the CBT group and two of the nine in the CT group improved), the participants in the CBT group benefited more.

Thus, at the general level, even our very short-term CBT seemed to be more effective than CT with more sessions. This is in line with our pre-hypothesis. However, at the level of individual measures, the evidence is limited. Rostain and Ramsay have argued that pharmacotherapy is a bottom-up treatment targeting the core symptoms of ADHD, and that CBT represents a top-down approach.Citation11 We assume that CT is mainly a bottom-up treatment, but since the participants received feedback from the tasks, and some of them were active in developing and testing their own strategies, a top-down approach was also embedded in it. However, it seems that CT is not as beneficial as the top-down CBT.

General discussion

More than half of our participants were medicated at the beginning of the treatment (five of the 10 in the CBT group, five of the nine in the CT group, and seven of the 10 in the control group). Their medication was required to be stabilized for three months before the treatment, and there were only minor changes in medication during the treatment. It can be assumed that the positive effects of pharmacotherapy were already obtained before entering the study, and therefore, the treatment benefits were not related to medication. Safren et alCitation12 found that better treatment results are gained when adding psychosocial treatment to pharmacotherapy. This is in line with our results where CBT seemed to be effective for already medicated participants.

Previously, only two psychosocial intervention studies of adult ADHD have used cognitive functioning as an outcome measure.Citation3,Citation8 In a study on mindfulness training,Citation8 improvement in tasks of attention and cognitive inhibition was found. In a pilot study using a structured skills training program in a group setting,Citation3 neuropsychological testing was used at baseline and following treatment, and some tendency towards improvement was found. However, a practice effect cannot be ruled out in either study since neither had a control group,Citation8 or when present, the control group did not undergo neuropsychological testing.Citation3 In our study, no treatment-related improvement was found in cognitive functioning as measured by CNSVS, a computerized neurocognitive test battery; that is, no more improvement was seen in the treatment groups than in the control group. In a study of Gualtieri and JohnsonCitation34 employing CNSVS, adults with ADHD were found to be impaired in measures of psychomotor speed, reaction time, cognitive flexibility, and attention when compared to normal controls. In our sample, some participants had difficulties in cognitive functioning measured by CNSVS, whereas some had no difficulties even though deficits had been reported in their previous neuropsychological examinations. The ceiling effect was also present in many participants in some of the tasks, especially in CPT (25 of the 29 participants received the maximum score of correct responses at T1) and in the Stroop test (26 of the 29 participants). Therefore we suggest that other, perhaps more sensitive, measures of cognitive functioning may also be needed.

Although it is not possible with this small sample to predict which participants would have the most improvement from CBT, we agree with Rostain and RamsayCitation11 that it would probably be those with a “more reasonable assessment of the treatment process and whose expectations about outcome were more realistic”. Our clinical impression was that the participants who were most motivated to learn new adaptive skills benefited most from the CBT. Also, those who benefited from the CT used their training sessions as an opportunity to develop and test their own ideas and strategies and did not just “mechanically” complete the tasks.

Concluding remarks

There are some limitations of the study that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the sample size was small in every group: 10 participants in the CBT group, nine participants in the CT group, and 10 in the control group. Thus, the results must be considered with caution. Second, although the participants were randomly assigned to either control or active treatment groups, the control group had no intervention during the follow-up. Therefore, possible placebo effects cannot be ruled out. Even so, blinded or sham treatments would be almost impossible to carry out reliably when studying these kinds of psychosocial treatments. The third limitation is related to the severity of the ADHD symptoms of the participants. In the independent evaluator’s CGI ratings, the participants were rated from mildly to markedly ill, thus no extreme cases were included. According to CGI, our participants had milder ADHD than, for example, Rostain and Ramsay had in their study, even though our CBT participants’ self-ratings in the BADDS total score were higher.Citation11 Thus, the independent evaluator’s personal rating style may have influenced the results. Also, the recruitment of the participants may have caused some bias towards more motivated and less severely disabled adults with ADHD participating in the study.

Despite these limitations, our study has many strengths. The diagnoses were made by a specialist and duly verified, the outcome measures were wide-ranging (self-report questionnaires, independent evaluations and neurocognitive testing), and we also used a control group and randomization in the study design. Some encouraging treatment benefits were obtained in the group that received short-term CBT, even though most of the participants were already receiving medication. However, CBT and CT studies with a larger sample size and more extensive cognitive testing are needed in the future. Also, the influence of treatment length and intensity needs to be studied.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by RAY, Finland’s Slot Machine Association. Maarit Virta received funding for preparation of this manuscript from the Rinnekoti Research Foundation. We are grateful to Pekka Lahti-Nuuttila for statistical support. The author report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DopheideJAPliszkaSRAttention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder: an updatePsychopharmacol Bull2009296656679

- TcheremissineOVSalazarJOPharmacotherapy of adult attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: review of evidence-based practices and future directionsExpert Opin Pharmacother2008981299131018473705

- HesslingerBTebartz van ElstLNybergEPsychotherapy of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults – A pilot study using a structured skills training programEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2002252417718412242579

- PhilipsenARichterHPetersJStructured group psychotherapy in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: results of an open multicentre studyJ Nerv Ment Dis2007195121013101918091195

- SolantoMVMarksDJMitchellKJWassersteinJKofmanMDDevelopment of a new psychosocial treatment for adult ADHDJ Atten Disord200811672873617712167

- StevensonCSWhitmontSBornholtLLiveseyDStevensonRJA cognitive remediation programme for adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorderAust N Z J Psychiatry200236561061612225443

- VirtaMVedenpääAGrönroosNAdults with ADHD benefit from cognitive-behaviorally oriented group rehabilitation – A study of 29 participantsJ Atten Disord200812321822618192618

- ZylowskaLAckermanDLYangMHMindfulness meditation training in adults and adolescents with ADHD: a feasibility studyJ Atten Disord200811673774618025249

- SalakariAVirtaMGrönroosNCognitive-behaviorally-oriented group rehabilitation of adults with ADHD: results of a 6-month follow-upJ Atten Disord201013551652319346466

- WilensTEMcDermottSPBiedermanJAbrantesAHahesyASpencerTJCognitive therapy in the treatment of adults with ADHD: A systematic chart review of 26 casesJ Cogn Psychother1999133215226

- RostainALRamsayJRA combined treatment approach for adults with ADHD – Results of an open study of 43 patientsJ Atten Disord200610215015917085625

- SafrenSAOttoMWSprichSWinettCLWilensTEBiedermanJCognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptomsBehav Res Ther200543783184215896281

- KlingbergTForssbergHWesterbergHTraining of working memory in children with ADHDJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol200224678179112424652

- KlingbergTFernellEOlesenPComputerized training of working memory in children with ADHD-a randomized, controlled trialJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200544217718615689731

- ShalevLTsalYMevorachCComputerized progressive attentional training (CPAT) program: effective direct intervention for children with ADHDChild Neuropsychol200713438238817564853

- SlateSEMeyerTLBurnsWJMontgomeryDDComputerized cognitive training for severely emotionally disturbed children with ADHDBehav Modif19982234154379670807

- OlesenPJWesterbergHKlingbergTIncreased prefrontal and parietal activity after training of working memoryNat Neurosci200471757914699419

- WhiteHAShahPTraining attention-switching ability in adults with ADHDJ Atten Disord2006101445316840592

- WardMFWenderPHReimherrFWThe Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention deficit hyperactivity disorderAm J Psychiatry199315068858908494063

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1994

- VirtaMSalakariAGrönroosNHypnotherapy for adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder – a randomized controlled studyContemp Hypnosis2010In press

- BrownTEAttention-Deficit Disorders and Comorbidities in Children, Adolescents, and AdultsWashington DCAmerican Psychiatric Press2000

- BrownTEAttention Deficit Disorder: The Unfocused Mind in Children and AdultsNew Haven, CTYale University Press2005

- VirtaMSalakariAVatajaRAD/HD aikuisten psykologinen yksilökuntoutus – Psykologin käsikirja [Rehabilitation for adults with AD/HD – Manual]Espoo, FinlandRinnekoti-Säätiö [Rinnekoti Foundation]2009

- MirskyAFAnthonyBJDuncanCCAhearnMBKellamSGAnalysis of the elements of attention: a neuropsychological approachNeuropsychol Rev1991221091451844706

- SohlbergMMMateerCAEffectiveness of an attention training programJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol1987921171303558744

- SohlbergMMMateerCAImproving attention and managing attentional problems: Adapting rehabilitation techniques to adults with ADHDAnn N Y Acad Sci200193135937511462753

- BrownTEBrown Attention-Deficit Disorder Scales for Adolescents and AdultsSan Antonio, TXThe Psychological Corporation1996

- KesslerRCAdlerLAmesMThe World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general populationPsychol Med200535224525615841682

- DerogatisLRLipmanRSCoviLSCL-90: An outpatient psychiatric rating scale – Preliminary reportPsychopharmacol Bull19739113284682398

- BeckATSteerRABrownGKBeck Depression Inventory Second Edition (BDI II)San Antonio, TXThe Psychological Corporation1996

- EndicottJNeeJHarrisonWBlumenthalRQuality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: a new measurePsychopharmacol Bull19932923213268290681

- GuyWECDEU Assessment Manual for PsychopharmacologyRockville MD, USDepartment of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs1976

- GualtieriCTJohnsonLGEfficient allocation of attentional resources in patients with AD/HD: maturational changes from age 10 to 29J Atten Disord20069353454216481670

- GualtieriCTJohnsonLGReliability and validity of a computerized neurocognitive test battery, CNS Vital SignsArch Clin Neuropsychol200621762364317014981

- GualtieriCTJohnsonLGA computerized test battery sensitive to mild and severe brain injuryMedscape J Med20081049018504479