Abstract

Aim:

To investigate post-traumatic stress, pain intensity, depression, and anxiety in patients with injury-related chronic pain before and after participating in multimodal pain rehabilitation.

Methods:

Twenty-eight patients, 21 women and seven men, who participated in the multimodal rehabilitation programs (special whiplash program for whiplash injuries within 1.5 years after the trauma or ordinary program) answered a set of questionnaires to assess post-traumatic stress (Impact of Event Scale [IES], pain intensity [Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)], depression, and anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HAD] before and after the programs.

Results:

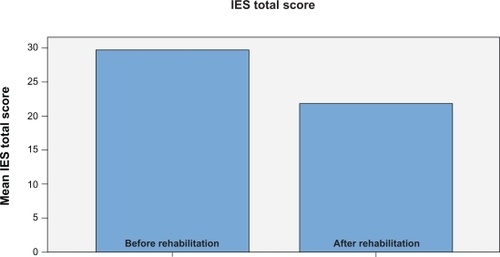

Both pain intensity and post-traumatic stress decreased significantly after the rehabilitation programs in comparison with before (VAS: 57.8 ± 21.6 vs. 67.5 ± 21.9; P = 0.009, IES total score 21.8 ± 13.2 vs. 29.5 ± 12.9; P < 0.001). Patients younger than 40 years reported a statistically higher level of post-traumatic stress compared with patients older than 40 years both before (P = 0.037) and after rehabilitation (P = 0.023). No statistically significant differences were found on the HAD scores.

Conclusion:

The multimodal rehabilitation programs were effective in reducing both pain intensity and post-traumatic stress. The experience of higher levels of post-traumatic stress in younger persons has to be taken into account when managing patients with injury-related chronic pain.

Introduction

Chronic pain, defined as pain that lasts for at least three months,Citation1 is very common. In Sweden prevalence of chronic pain is estimated to be between 40% and 55%Citation2–Citation4 and accounts for the majority of long-time sick leave.Citation5 Many factors, together or by themselves may contribute to the development of long-lasting pain, including chronic sensitization of nociceptors, derangements in the antinociceptive system and psychosomatic interaction.Citation6,Citation7

Most chronic pain is musculoskeletal pain,Citation4 caused, for example by injuries such as whiplash. In Sweden, the incidence of whiplash injuries varies from 1.0 to 3.2/1000 per year.Citation8,Citation9 Whiplash injuries result from an acceleration-deceleration movement that indirectly transfers energy to the neck, resulting in a soft tissue injury/distortion of the neck.

A frequent cause of whiplash injuries is traffic injuries, especially rear-end collisions. Although many patients recover within a few months after an accident, a significant proportion experiences prolonged symptoms that may result in limitations in work and in leisure time.Citation9,Citation10 Whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) are clinical manifestations resulting from whiplash injuries.Citation11 The dominating complaints are neck pain and headache, but fatigue, dizziness, irritability, anxiety, and pain arising from the shoulders and thoracic vertebral column are common symptoms.Citation8,Citation9,Citation12

Patients suffering from chronic pain after accidents can also develop psychological issues, such as post-traumatic stress reactions.Citation13,Citation14 During the first year after a vehicle accident many patients (10%–30%) are diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).Citation15

Post-traumatic stress symptoms are characterized by three major symptom clusters: re-experiencing symptoms, avoidance symptoms, and arousal symptoms. Other frequent symptoms seen among patients with post-traumatic stress include tiredness, dizziness, irritability, sleeping disorders, and a lower ability to concentrate.Citation15 It has been proposed that there are factors common to pain and post-traumatic stress that maintain both conditionsCitation14 and the co-occurence of chronic pain and post-traumatic stress have been documented both in patients following traffic injuriesCitation16 and in veterans.Citation17–Citation19 These findings may have consequences for patients who suffer from both chronic pain and post-traumatic stress as they may experience more intense pain and affective stress, greater disability and decreased life satisfaction than patients with only one of the diagnoses.Citation20,Citation21 Moreover the level of post-traumatic stress has been shown to be a prognostic factor for developing persistent symptoms among patients with chronic pain after an accident, especially after whiplash injuries.Citation14 Therefore, the Swedish Society of Medicine and the Whiplash Commission task force have declared that post-traumatic stress symptoms should be diagnosed and treated early after injury in order to minimize the risk for long-lasting symptoms.Citation22 Although studies of long-term outcome after WAD have identified risk factors such as increased age, gender and initial pain intensityCitation12,Citation23 the literature is inconsistent.Citation24 However, attention have been paid to the influence of gender as a potential prognostic factor, and female gender has been associated with the development of chronic pain; Citation25 more women than men have also been shown to suffer from post-traumatic stress symptoms.Citation26 Moreover, patients with chronic pain and WAD do not constitute a homogenous population since several factors may coexist and interact. Due to the complexity of injury-related pain, the importance of identifying different subgroups has been proposed.Citation27

Since chronic pain and disability are influenced by a complex interaction of physical, psychological, and social factors, the biopsychosocial model has been adopted in multimodal pain rehabilitation interventions.Citation28,Citation29 These are currently based on cognitive – behavioral principles. A number of studies have shown positive effects of multidisciplinary treatments and multimodal rehabilitation of chronic pain.Citation30

As part of regular procedures at the Pain Rehabilitation Clinic at the Umeå University Hospital, patients complete questionnaires that are included in the Swedish National Quality Registry for Pain Rehabilitation (NRS) after participating in the rehabilitation programs. However, there is no systematic follow-up of post-traumatic stress symptoms.

The aims of this pilot-study were therefore: (i) to investigate the occurrence and levels of post-traumatic stress among patients before and after participating in pain rehabilitation programmes; (ii) to assess relationships between the level of post-traumatic stress and pain intensity, anxiety, depression, activity level, and life satisfaction; and (iii) to examine any possible difference in post-traumatic stress between different age groups, younger, and older patients.

Methods

Patients and procedure

This pilot study includes 28 patients, 21 women and seven men, mean age 36 years ± (range: 21–53 years), who were admitted for rehabilitation to the Pain Rehabilitation Clinic at the University Hospital, Umeå, Sweden because of chronic musculoskeletal pain caused by an injury sustained between April 2006 to March 2007. Whiplash injury caused the trauma in 20 patients and other types of accidents (such as falling or being hit by a tree) caused the trauma in eight patients. Three patients had an additional accident within four years before the actual trauma. About 50% of the patients were on full-time sick leave when they began the rehabilitation program, 17.9% were on part-time sick leave, and 28.6% were working or studying. In the referrals from the primary care physicians, only pain symptoms (no post-traumatic stress-related symptoms) were described. Most patients had an upper secondary school education (20 patients), some had a university education (seven patients), and one had a compulsory school education. To compare age groups, patients were divided into “younger than 40 years” (10 patients) and “older than 40 years” (12 patients).

Eighteen patients (64.3%) participated in a special program (WAD program) for patients with whiplash injuries within 1.5 years of their accident and 10 patients participated in a regular rehabilitation program for patients with chronic pain of other origins. Both rehabilitation programs were based on cognitive–behavioral principles and consisted of daily sessions six hours a day for five weeks. Each patient received a personal schedule and had their own team that consisted of a clinical psychologist trained in cognitive – behavior skills, an occupational therapist, a physiotherapist, a specialist physician in rehabilitation medicine, and a social worker. The whiplash program was more focused on the whiplash injury, but both programs included components of education about chronic pain, about bodily and psychological reactions to pain, and about pain management. Both programs included activity exercises, psychoeducational group therapy that focused on coping strategies and assertiveness training, post-traumatic stress, relaxation and body awareness training.

Before and after participating in the rehabilitation programs patients completed questionnaires that are included in the NRS. The questionnaires ask the patients to estimate their level of discomfort and pain using several instruments: the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)Citation31 for pain intensity; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD)Citation32 for anxiety and depression; the Disability Rating Index (DRI)Citation33 for activity level; and the Life Satisfaction checklist (LiSat-11)Citation34 for life satisfaction. To guarantee quality and to evaluate rehabilitation work, the answers were registered in the NRS. Data about the patients participating in the study were collected from the NRS. Other information, such as sick leave, the cause of accident and which programs patients had participated in were collected from hospital records.

Instruments

Post-traumatic stress

The Impact of Event Scale (IES)Citation35 measures the level of post-traumatic stress. The IES, a screening tool that includes 15 statements about particular difficulties associated with stressful life events, asks patients to rate (0 = never, 1 =seldom, 3 = sometimes, 5 = often) the degree to which a statement describes their previous week. The total score of the 15 statements is 75 and the score is divided into four grades or stress reactions: sub-clinical (0–8), mild (9–25), moderate (26–43), and severe (44–75). Seven statements address intrusive symptoms such as sleeping difficulties because of thinking about the accident and having unexpected sudden flashbacks of the accident. Eight statements address avoidance symptoms, such as avoiding things or situations that could be a reminder of the accident. The total IES scale includes the intrusion and the avoidance subscales. The IES has been validated and found to be a useful measure of stress reactions in a large number of populations exposed to various traumatic experiences, including road traffic accidents and have been used in previous studies regarding whiplash injuriesCitation36,Citation37

Pain intensity

The VASCitation31 is an instrument that measures pain intensity. The patients mark their experienced pain on a 100 mm straight line, where 0 means “no pain” and 100 “worst pain imaginable”.

Depression and anxiety

The HADCitation32 is an instrument that is used to find and to estimate the level of anxiety and depression. It consists of seven questions rating anxiety and seven questions rating depression. Each question gives a score from 0 to 3 points. If the patient scores 8–10 points in one category it is considered a limit value for mild to moderate symptoms. More than 10 points indicates severe symptoms.

Level of activity

The Disability Rating Index (DRI)Citation33 comprises 12 questions about ordinary activities, for example walking, running, sitting, standing, carrying, lifting, making the bed etc. The patients estimate their activity level on a 0 to 100-mm visual analogue scale, where 0 means “manages without difficulty” and 100 means “does not manage at all”.

Life satisfaction

The Life Satisfaction checklist (LiSat-11)Citation34 questionnaire estimates a patient’s level of life satisfaction in 11 areas: life as a whole, profession/situation on the labour market, economy, leisure time, contacts with familiar and friends, sexual life, activities of daily living, family life, partner, somatic health and psychological health. Levels of satisfaction are estimated on a 6-point response scale, from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied”.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with Statistic Package for Social Sciences software (v. 17.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data are reported as means ± standard deviations. For comparison between before and after rehab programs Wilcoxon signed-ranks-test was used. Comparisons between men and women and different age groups were made using the Mann–Whitney U-test. For calculating the correlation between IES and VAS, DRI, HAD and LiSat-11 before and after the rehabilitation program, Spearman’s correlation test was used. Statistical significant level was set at P < 0.05. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Umeå University.

Results

Post-traumatic stress

Post-traumatic stress was assessed using the IES. In all patients the number of post-traumatic stress- related symptoms decreased significantly (P = 0.014) after the rehabilitation programs (8.9 ± 4.5) compared to before the rehabilitation programs (11.0 ± 3.5). In all patients, post-traumatic stress scores also decreased significantly after participating in rehabilitation programs with respect to the total IES scale (before, 29.5 ± 1.9; after, 21.8 ± 13.2; P < 0.001) as well as the subscale intrusion (before, 16.1 ± 6.8; after; 11.4 ± 7.5; P < 0.001) and avoidance (before, 13.4 ± 8.9; after, 10.4 ± 8.5; P = 0.031) compared to the post-traumatic stress levels before the program (, ; ).

Figure 1 Total IES score before (29.5 ± 12.9; range: 1–57) and after (21.8 ± 13.2; range: 1–49) in all patients (n = 28).

Table 1 Before rehabilitation

Table 3 After rehabilitation

The levels of post-traumatic stress are shown in and ; according to the subclassification by Kongsted and colleagues,Citation36 mild stress response was observed in 39.2% before rehabilitation (subclinical and mild stress reactions) and distinct stress response was present in 60.7% (moderate and severe stress reactions). After rehabilitation 64.3% reported mild stress response (subclinical and mild stress reactions) and distinct stress response was reported by 35.7%.

Table 2 Level of stress reaction before rehabilitation

Post-traumatic stress in gender and age groups

The IES scores with respect to gender are shown in and . There was no statistically significant difference between men and women before and after participating in rehabilitation programs concerning the scores on the total IES scale (men before, 26.1 ± 9.3; women before, 30.6 ± 13.9; P = 0.376; men after, 17.4 ± 13.5; women after, 23.2 ± 13.1; P = 0.249) or the subscales intrusion (men before, 16.0 ± 4.6; women before, 16.2 ± 7.5; P = 0.979; men after, 10.7 ± 8.0; women after, 11.6 ± 7.5; P = 0.796), and avoidance (men before, 10.1 ± 5.9; women before, 14.4 ± 9.6; P = 0.321; men after, 6.7 ± 6.5; women after, 11.6 ± 8.8; P = 0.228).

For comparison between two age groups, patients were divided into the following groups: “younger than 40 years” (n = 16) and “older than 40 years” (n = 12). The age group younger than 40 years reported a statistically significantly higher scores of post-traumatic stress compared with patients older than 40 years before rehabilitation programs on the total IES scale (younger, 33.8 ± 10.9; older, 23.7 ± 13.6; P = 0.037) and the subscale intrusion (younger, 18.4 ± 6.4; older, 13.2 ± 6.5; P = 0.042) (), as well as after rehabilitation programs on the total IES scale (younger, 26.3 ± 0.8; older, 15.7 ± 14.2; P = 0.023) and the subscale intrusion (younger, 14.1 ± 7.4; older, 7.7 ± 6.1; P = 0.029) (). No significant difference was found between the age groups on the subscale avoidance before rehabilitation (younger, 15.4 ± 8.8; older, 10.6 ± 8.7; P = 0.189) () or after rehabilitation (younger, 12.2 ± 8.0; older, 8.0 ± 8.8; P = 0.133) (). The levels of post-traumatic stress with respect to genders and age-groups are shown in and .

Table 4 Level of stress reaction after rehabilitation

Comparison of post-traumatic stress between the two rehabilitation programs

When comparing patients who participated in the WAD program with patients participating in the regular rehabilitation program before and after rehabilitation no statistically significant differences were found concerning the number of post-traumatic stress-related symptoms (before, P = 0.942; after, P = 0.322), the level of post-traumatic stress on the total IES scale (before, P = 0.456; after, P = 0.113) or on the IES subscales (intrusion before, P = 0.203; after, P = 0.230; avoidance before, P = 0.581; after, P = 0.229).

Pain intensity, disability, depression, anxiety, and life satisfaction

Pain intensity on the VAS was significantly decreased (P = 0.009) for all patients after the rehabilitation program (57.8 ± 21.6) () in comparison with before (67.5± 21.9) (). No statistically significant differences were found when comparing the scores of the HAD anxiety and depression scales ( and ), the total DRI scale, and the total LiSat-11 scale before and after the rehabilitation program (P > 0.05). Some of the separate items showed a statistically significant improvement after the rehabilitation program in comparison with before the program: light work on the DRI (P = 0.007) and psychological health on the LiSat-11 (P = 0.011).

Correlations

Statistically significant correlations were shown between the scores of IES and HAD anxiety, both before and after rehabilitation programs (before, r = 0.570, P = 0.002; after, r = 0.637, P < 0.001). The IES score after rehabilitation was also statistically significantly correlated to the HAD depression scores (r = 0.399, P = 0.036); no such correlation was found before rehabilitation. No statistical significant correlation was found between the scores of IES and the VAS, DRI, and LiSat-11 scores.

Discussion

This pilot study shows that the level of post-traumatic stress as well as the number of post-traumatic stress-related symptoms and pain intensity significantly decreased in patients after participating in the multimodal pain rehabilitation programs. These programs include multidisciplinary treatment and are based on cognitive–behavioral principles. The aim is to reduce disability in patients with chronic pain and both physiological and psychological factors are focused on. In the literature of pain rehabilitation a number of studies have shown that multidisciplinary interventions are more effective than nondisciplinary treatments.Citation30 Several studies have investigated post-traumatic stress after vehicle accidentsCitation38 and interventions that include cognitive–behavioral treatment have also been shown to decrease post-traumatic stress.Citation39–Citation41 In a randomized controlled study, Blanchard and colleaguesCitation42 studied different methods of treatments for PTSD in patients who had survived a vehicle accident (on an average of 13 months earlier). The authors found that cognitive therapy, in comparison with psychotherapy support or being placed on a waiting list, more effective decreased post-traumatic stress. In their study, the significant improvement in PTSD was also sustained at the follow-up three months after the treatment. In a recent study by Otis and colleaguesCitation19 of veterans with chronic pain and PTSD, a combination of cognitive processing therapy and cognitive–behavioral therapy for an integrative treatment of both disorders showed positive results. These findings may have implications in the future for treatment design of patients with injury-related chronic pain.

In the present study, the IES was used to assess post-traumatic stress. This instrument has been used in previous studies of post-traumatic stress in vehicle related accidents mostly in whiplash injuries.Citation36–Citation38,Citation43 The levels of post-traumatic stress with 60.7% of patients suffering from moderate to severe stress before rehabilitation were clearly higher than previously reported early after injury (13%)Citation36 but also higher comparing with previous results from our clinic (48%).Citation44 However, the post-traumatic stress levels decreased noticeably during the rehabilitation programs; only 35.7% reported moderate to severe stress after rehabilitation.

Moreover, when time since trauma was compared between the two groups participating in rehabilitation programs, there was a considerable difference from the time of the accident to when the patients began the two different rehabilitation programs; approximately 1.5 years for the patients in the WAD program compared with approximately five years for the patients in the general rehabilitation program. Despite the difference in time, there was no significant difference between the level of post-traumatic stress in the patients participating in the WAD program compared with patients in the general rehabilitation program, neither before nor after the programs. However, to optimize the results it seems obvious that patients should have been offered rehabilitation earlier. Recently, Sullivan and colleagues pointed out the importance of early adequate management of pain symptoms and disability in whiplash patients to reduce the severity of post-traumatic stress symptoms.Citation45 The Swedish Society of Medicine and the Whiplash Commission task forceCitation22 have called attention to the importance of observing and treating PTSD in patients with whiplash injuries in order to minimize the risk for long-lasting symptoms. Concerning the patients in both the WAD and the general pain rehabilitation programs, no post-traumatic stress-related symptoms were described in the referrals prepared by the primary care physicians who had referred the patients. This indicates that these symptoms had not been observed earlier and this may have had an effect on the development of the patients’ chronic pain symptoms.

In this study, the patients in the group younger than 40 years had a greater number of and more severe post-traumatic stress symptoms in comparison with the group of patients older than 40 years. Earlier studies of post-traumatic stress among individuals in different age groups have shown different results. For example, older individuals have been reported to experience less post-traumatic stress than younger, which may be because older individuals may work through traumatic episodes much earlier than younger individuals, an approach that may enhance their ability to cope with new traumas.Citation46 Not only has it been shown that higher age could imply a higher risk of developing post-traumatic stress symptoms,Citation47 but at the same time it also has been reported that no difference concerning post-traumatic stress measured with the instrument IES could be found between younger, older and middle-aged individuals.Citation48

There was no significant difference in experienced post-traumatic stress symptoms between men and women in the present study. Other studies with a greater number of patients have shown that women suffer from more post-traumatic stress than men.Citation26,Citation49 It is possible that differences between genders concerning the presence of post-traumatic stress among patients with chronic pain are due to the study populations.

The correlation between IES and HAD anxiety was significant, which shows a clear relationship between the level of post-traumatic stress symptoms and anxiety. This link is also described in earlier literature and may be caused by an interaction between these symptoms.Citation50

In the present study, patients rated pain intensity on VAS. The mean scores were high in compared to previous studies of whiplash patients and patients with chronic painCitation25,Citation38,Citation44 and clearly higher than reported by Roth and colleaguesCitation16 of patients with injury-related chronic pain referred to a pain rehabilitation program. However, in contrast to some previous studies, no significant association was found between pain intensity and post-traumatic stress.Citation16,Citation44 These findings may be due to the small study population in our study.

The present study has several limitations. First, despite the fact that a small group of patients participated in this pilot study and that there is no long-term follow-up, the decrease of post-traumatic stress and pain intensity during the multimodal rehabilitation programs is a promising result. With regard to future research, it would be useful to investigate a larger study population with a long time follow-up. In our pilot study, we did not include a control group. Future studies could use waiting list controls and should focus on the long-term effects of rehabilitation programs on pain and post-traumatic stress. Moreover, since the population was small and several instruments were included, we cannot rule out the possibility of type I and type II errors.

In conclusion, the multimodal rehabilitation program was effective in reducing both pain intensity and post-traumatic stress. The experience of higher levels of post-traumatic stress in younger persons has to be taken into account when managing patients with injury-related chronic pain. Continuously using the IES questionnaires, in addition to the ordinary instruments at our clinic for patients with chronic pain, could lead to increased knowledge and a possibility to detect post-traumatic stress. This could lead to a modified strategy of treatment and rehabilitation.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Pain terms: A list of definitions and notes on usage Recommended by the IASP Subcommittee on TaxonomyPain19796249252460932

- BrattbergGThorslundMWikmanAThe prevalence of pain in a general population. The results of a postal survey in a county of SwedenPain19893722152222748195

- AnderssonHIEjlertssonGLedenIRosenbergCChronic pain in a geographically defined general population: studies of differences in age, gender, social class, and pain localizationClin J Pain1993931741828219517

- GerdleBBjorkJHenrikssonCBengtssonAPrevalence of current and chronic pain and their influences upon work and healthcare-seeking: a population studyJ Rheumatol20043171399140615229963

- LundbergDAxelssonSBoiveJMetoder för behandling av långvarig smärta En systematisk litteraturöversiktStockholm, SwedenThe Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care2006

- MenseSThe pathogenesis of muscle painCurr Pain Headache Rep20037641942514604500

- SullivanMJRodgersWMKirschICatastrophizing, depression and expectancies for pain and emotional distressPain2001911214715411240072

- HerrstromPLannerbro-GeijerGHogstedtBWhiplash injuries from car accidents in a Swedish middle-sized town during 1993–1995Scand J Prim Health Care200018315415811097100

- SternerYToolanenGGerdleBHildingssonCThe incidence of whiplash trauma and the effects of different factors on recoveryJ Spinal Disord Tech200316219519912679676

- SpitzerWOSkovronMLSalmiLRScientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its managementSpine1995208 Suppl1S73S7604354

- BarnsleyLLordSBogdukNWhiplash injuryPain19945832833077838578

- RadanovBPdi StefanoGSchnidrigABallinariPRole of psychosocial stress in recovery from common whiplashLancet199133887697127151679865

- KuchKCoxBJEvansRJPosttraumatic stress disorder and motor vehicle accidents: a multidisciplinary overviewCan J Psychiatry19964174294348884031

- SharpTJHarveyAGChronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: mutual maintenance?Clin Psychol Rev200121685787711497210

- MayouRBryantBPsychiatry of whiplash neck injuryBr J Psychiatry200218044144811983642

- RothRSGeisserMEBatesRThe relation of post-traumatic stress symptoms to depression and pain in patients with accident-related chronic painJ Pain20089758859618343728

- ShipherdJCKeyesMJovanovicTVeterans seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: what about comorbid chronic pain?J Rehabil Res Dev200744215316617551870

- OtisJDKeaneTMKernsRDAn examination of the relationship between chronic pain and post-traumatic stress disorderJ Rehabil Res Dev200340539740515080224

- OtisJDKeaneTMKernsRDMonsonCScioliEThe development of an integrated treatment for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorderPain Med20091071300131119818040

- TurkDCOkifujiAPerception of traumatic onset, compensation status, and physical findings: impact on pain severity, emotional distress, and disability in chronic pain patientsJ Behav Med19961954354538904727

- ShermanJJTurkDCOkifujiAPrevalence and impact of posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms on patients with fibromyalgia syndromeClin J Pain200016212713410870725

- JansenGBEdlundCGranePWhiplash injuries: diagnosis and early management. The Swedish Society of Medicine and the Whiplash Commission Medical Task ForceEur Spine J200817Suppl 3S355S41718820955

- KyhlbackMThierfelderTSoderlundAPrognostic factors in whiplash-associated disordersInt J Rehabil Res200225318118712352171

- WilliamsonEWilliamsMGatesSLambSEA systematic literature review of psychological factors and the development of late whiplash syndromePain200813512203018222038

- BerglundABodinLJensenIWiklundAAlfredssonLThe influence of prognostic factors on neck pain intensity, disability, anxiety and depression over a 2-year period in subjects with acute whiplash injuryPain2006125324425616806708

- UrsanoRJFullertonCSEpsteinRSAcute and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victimsAm J Psychiatry1999156458959510200739

- SternerYGerdleBAcute and chronic whiplash disorders–a reviewJ Rehabil Med2004365193209 quiz 210.15626160

- GatchelRJPengYBPetersMLFuchsPNTurkDCThe biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directionsPsychol Bull2007133458162417592957

- McLeanSAClauwDJAbelsonJLLiberzonIThe development of persistent pain and psychological morbidity after motor vehicle collision: integrating the potential role of stress response systems into a biopsychosocial modelPsychosom Med200567578379016204439

- ScascighiniLTomaVDober-SpielmannSSprottHMultidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomesRheumatology200847567067818375406

- ScrimshawSVMaherCResponsiveness of visual analogue and McGill pain scale measuresJ Manipulative Physiol Ther200124850150411677548

- ZigmondASSnaithRPThe hospital anxiety and depression scaleActa Psychiatr Scand19836763613706880820

- SalenBASpangfortEVNygrenALNordemarRThe Disability Rating Index: an instrument for the assessment of disability in clinical settingsJ Clin Epidemiol19944712142314357730851

- Fugl-MeyerARMelinRFugl-MeyerKSLife satisfaction in 18- to 64-year-old Swedes: in relation to gender, age, partner and immigrant statusJ Rehabil Med200234523924612392240

- HorowitzMWilnerNAlvarezWImpact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stressPsychosom Med1979413209218472086

- KongstedABendixTQeramaEAcute stress response and recovery after whiplash injuries. A one-year prospective studyEur J Pain200812445546317900949

- SterlingMKenardyJJullGVicenzinoBThe development of psychological changes following whiplash injuryPain2003106348148914659532

- ShipherdJCBeckJGHamblenJLLacknerJMFreemanJBA preliminary examination of treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in chronic pain patients: a case studyJ Trauma Stress200316545145714584629

- TaylorSFedoroffICKochWJThordarsonDSFecteauGNickiRMPosttraumatic stress disorder arising after road traffic collisions: patterns of response to cognitive-behavior therapyJ Consult Clin Psychol200169354155111495183

- JaspersJPWhiplash and post-traumatic stress disorderDisabil Rehabil199820113974049846239

- PalyoSABeckJGPost-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, pain, and perceived life control: associations with psychosocial and physical functioningPain20051171212112716098670

- BlanchardEBHicklingEJDevineniTA controlled evaluation of cognitive behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress in motor vehicle accident survivorsBehav Res Ther2003411799612488121

- StålnackeBMRelationship between symptoms and psychological factors five years after whiplash injuryJ Rehabil Med200941535335919363569

- ÅhmanSStålnackeBMPost-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety in patients with injury-related chronic pain: A pilot studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2008461245124919337465

- SullivanMJThibaultPSimmondsMJMiliotoMCantinAPVellyAMPain, perceived injustice and the persistence of post-traumatic stress symptoms during the course of rehabilitation for whiplash injuriesPain2009145332533119643543

- LyonsJStrategies for assessing the potential for positive adjustment following traumaJ Traumatic Stress1991493111

- LyonsJMMcClendonOBChanges in PTSD symptomatology as a function of agingNova-Psy Newslett199081318

- ChungMCWerrettJEasthopeYFarmerSCoping with post-traumatic stress: young, middle-aged and elderly comparisonsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200419433334315065226

- FullertonCSUrsanoRJEpsteinRSGender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidentsAm J Psychiatry200115891486149111532736

- BeckJGGrantDMReadJPThe Impact of Event Scale-Revised: Psychometric properties in a sample of motor vehicle accident survivorsJ Anxiety Disord200822218719817369016