Abstract

Migraine is a common, disabling disorder associated with considerable personal and societal burden. Current guidelines recommend triptans for the acute treatment of migraine unlikely to respond to less effective therapies. Rizatriptan is a second-generation triptan available in tablet or orally disintegrating tablet (wafer) formulations that offers several advantages over other members of its class. Rizatriptan is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and achieves maximum plasma concentrations more quickly than other triptans, providing rapid pain relief. Clinical trials have shown that rizatriptan is at least as effective or superior to other oral migraine-specific agents in the acute treatment of migraine, and has more consistent long-term efficacy across multiple migraine attacks. Rizatriptan has a favorable tolerability profile, and patients have reported greater satisfaction and a preference for rizatriptan over other migraine-specific agents. Improvements in quality of life reported with rizatriptan are consistent with its favorable efficacy and tolerability profiles. Notably, multi-attribute decision models that combine clinical data with patient- and physician-reported treatment preferences have identified rizatriptan as one of three triptans closest to a hypothetical “ideal”. The efficacy and tolerability of rizatriptan for the acute treatment of migraine have thus been well established.

Introduction

Background and epidemiology

Migraine is a common, disabling disorder that affects approximately 3%–22% of females and 1%–16% of males worldwide (CitationLipton and Bigal 2005). Results of a large population-based study performed in the US suggest that migraine affects approximately 18.2% of women and 6.5% of men, of whom most (62%) experience at least 1 severe headache per month (CitationLipton, Stewart, et al 2001). Migraine without aura is the commonest clinical subtype of migraine, and has a higher attack frequency and is generally more disabling than migraine with aura (CitationHCS 2004). Migraine without aura is defined as a recurrent disorder that involves headache attacks lasting 4 hours to 3 days, with at least 2 of the following characteristics: unilateral pain, pulsating quality, aggravation on movement, and pain of moderate or severe intensity (CitationHCS 2004). Patients with this migraine subtype also experience nausea and/or vomiting, and/or photophobia and phonophobia (CitationHCS 2004).

Migraine places a considerable burden on the sufferer, their friends and family, and society, in terms of economic costs and quality of life. Direct costs of migraine include visits to physicians, utilization of emergency care facilities, and prescription and over-the-counter medications (CitationLipton and Bigal 2005). The majority of the not inconsiderable indirect costs are borne by patients and their employers, predominantly as a result of bedridden days and impaired work function (CitationHu et al 1999). A recent analysis, based principally on studies performed prior to 1995, estimated that the annual cost of migraine in some Western European countries was approximately €590 per patient, primarily due to lost productivity (CitationBerg and Stovner 2005). Lost productivity due to headache (including but not limited to migraine) is estimated to cost more than US$19 billion per year in the US, with migraine accounting for at least US$13 billion per year (CitationHu et al 1999).

The results of several studies indicate that migraine affects quality of life during and immediately after a migraine attack, as well as reducing quality of life between episodes (CitationLipton and Bigal 2005). Population-based studies in the UK and US demonstrate that migraine attacks also have a significant impact on family members of afflicted individuals (CitationLipton et al 2003). Moreover, a survey of migraine sufferers found that less than one-third of patients were “very satisfied” with their acute migraine treatment (CitationLipton and Stewart 1999). Thus, migraine remains a major healthcare problem, and there is significant opportunity to improve the treatment and management of this condition.

Current treatments

There are a number of abortive therapy options for acute migraine. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, nonopiate analgesics, and combination analgesics may be appropriate for some patients with mild-to-moderate migraine. Patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms or those who respond poorly to adequate doses of analgesics generally require migraine-specific agents or more potent nonspecific agents such as opiate analgesics, although the latter should be used sparingly (CitationSilberstein and for the US Headache Consortium 2000; CitationGoadsby et al 2002). Anti-emetics may be used to treat migraine-associated nausea, and may also facilitate absorption of oral migraine treatments by improving gastric motility.

The two principal classes of migraine-specific agents (ie, those targeting the neurovasculature) are the ergot derivatives and the triptans. The ergot derivatives ergotamine and dihydroergotamine have been used for the acute treatment of migraine for many years. However, they have a number of limitations including nonspecific vasoconstrictor effects and other side-effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) owing to a low degree of receptor selectivity, and there is a lack of consistent efficacy data for these agents (CitationTfelt-Hansen, Saxena, et al 2000). Improved understanding of the pathology of migraine led to the development of selective serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) receptor agonists (triptans) that activate 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors. Triptans are now generally preferred over ergot derivatives in treating most patients with migraine, because of advantages including selective pharmacology and well-established efficacy and safety (CitationGoadsby et al 2002).

Sumatriptan was the first triptan to be introduced for the treatment of migraine attacks, and is commonly used as the reference against which later triptans are compared (CitationFerrari et al 2002). Although clinical trial results show only relatively small differences between sumatriptan and newer, second-generation triptans for efficacy and tolerability, these differences are considered clinically relevant for individual patients (CitationFerrari et al 2002). This article reviews the evidence relating to rizatriptan, a second-generation triptan available in 5- and 10-mg tablets and orally disintegrating tablets (wafers) for the acute treatment of migraine.

Pharmacology

Animal and preclinical results

Several pharmacologic effects of the 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonist rizatriptan are thought to contribute to its antimigraine activity, including vasoconstriction of intracranial extracerebral blood vessels (CitationLongmore et al 1998), inhibition of nociceptive neurotransmission in trigeminal pain pathways (CitationCumberbatch et al 1997), and inhibition of neurogenic dural vasodilation and plasma protein extravasation (CitationWilliamson et al 1997; CitationWilliamson et al 2001).

Preclinical studies showed that rizatriptan caused vasoconstriction in isolated human cranial (middle meningeal) arteries (CitationLongmore et al 1998) with an EC50 (concentration required to produce 50% of maximum vasoconstriction) of 90 nM, which is similar to the maximum plasma concentrations achieved following oral administration of a single 5- or 10-mg rizatriptan dose in healthy individuals (30–70 nM) (CitationSciberras et al 1997). The vasoconstrictor action of rizatriptan is thought to occur primarily via 5-HT1B receptors (CitationLongmore et al 1998; CitationGoadsby and Hargreaves 2000). A study in healthy volunteers showed that rizatriptan significantly reduced cerebral blood flow and arterial-to-capillary blood volume consistent with its vasoconstrictor activity in large cerebral arteries, with a recovery pattern indicating no alteration of the autoregulatory response of small arteries (Okazawa et al 2005). Another study in healthy volunteers found no effect of rizatriptan 40 mg on regional cerebral blood flow (CitationSperling and Tfelt-Hansen 1995). Furthermore, rizatriptan did not significantly alter cerebral blood flow velocity during attacks in patients with migraine without aura as compared with pretreatment or pain-free values, a finding that may support the cerebrovascular safety of the drug (CitationGori et al 2005). Although, like other triptans, rizatriptan has also been shown to contract isolated human coronary arteries in vitro (CitationLongmore et al 1997; CitationMaassenVanDenBrink et al 1998), the EC50 for this effect (700–1000 nM) (CitationLongmore et al 1997) is so high that rizatriptan is considered unlikely to cause myocardial ischemia at therapeutic plasma concentrations in patients with normal coronary circulation (CitationMaassenVanDenBrink et al 1998). Rizatriptan 10 mg demonstrated only minimal and transient vasoconstrictor effects on peripheral arteries in normal human subjects (CitationTfelt-Hansen et al 2002).

Pharmacokinetics

Rizatriptan is rapidly and completely (~90%) absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract following administration of the oral tablet, with an absolute bioavailability of 47% owing to moderate first-pass metabolism (CitationVyas et al 2000). The mean time to maximum plasma concentration (tmax) following a single rizatriptan 10-mg tablet in healthy volunteers is approximately 1–1.5 hours (CitationSciberras et al 1997; CitationGoldberg et al 2000; CitationVyas et al 2000), which is shorter than that of other available triptans (CitationFerrari et al 2002). Rizatriptan has a relatively short plasma half-life (t1/2) of approximately 2–2.5 hours (CitationSciberras et al 1997; CitationLee et al 1999; CitationGoldberg et al 2000; CitationVyas et al 2000). A pharmacokinetic study in healthy males showed no unexpected accumulation of rizatriptan 10 mg following administration of multiple doses (every 2 hours for 3 doses on 4 consecutive days) (CitationGoldberg et al 2000). Rizatriptan wafers have a similar pharmacokinetic profile to tablets, although they have a slower rate of absorption (mean tmax 1.6–2.5 hours) (CitationMerck & Co Inc. 2003).

Metabolism is the primary route of elimination of rizatriptan, with renal elimination accounting for only 25% of total plasma clearance (CitationVyas et al 2000). Rizatriptan is metabolized predominantly by monoamine oxidase A, accounting for 51% of urinary rizatriptan metabolites (CitationVyas et al 2000). The clearance of rizatriptan is approximately 25% higher in males than in females (plasma clearance 1042 vs 821 mL/min, respectively); however, this is not thought to be clinically relevant (CitationLee et al 1999).

Importantly, rizatriptan mean plasma concentrations and tmax are not affected by the occurrence of a migraine attack (and associated gastric stasis) (CitationCutler et al 1999). Administration of food prior to rizatriptan dosing in healthy volunteers was found to increase the area under the curve (AUC) by approximately 20% and delay absorption, but there were no significant effects on maximum concentration (Cmax) or tmax values (CitationCheng et al 1996). The pharmacokinetics of rizatriptan in elderly patients (aged ≥ 65 years) are similar to those in younger patients (CitationMusson et al 2001). Since the major route of elimination of rizatriptan, oxidative deamination, is catalyzed by monoamine oxidase A, inhibitors of cytochrome P-450 are expected to have minimal effects on the pharmacokinetics of rizatriptan (CitationVyas et al 2000). Patients receiving propranolol exhibit an increase in plasma rizatriptan concentration (CitationGoldberg et al 2001), possibly reflecting competitive inhibition of monoamine oxidase A rizatriptan metabolism. Rizatriptan dose-reduction is therefore recommended in patients receiving propranolol (see patient support–disease management programs section).

Clinical studies

Efficacy

Recommended efficacy measures in clinical trials of migraine treatments include the percentage of patients who are pain-free at 2 hours following treatment, headache response–pain relief at 2 hours (reduction in intensity of the headache from severe or moderate at baseline to mild or none), sustained pain-free response rate (pain-free status within 2 hours with no rescue medication use or migraine recurrence within 48 hours), time to headache response or pain-free status (ie, speed of onset of action), and the need for rescue medications within 2 hours of treatment (CitationTfelt-Hansen, Block, et al 2000).

The efficacy of rizatriptan 5 and 10 mg in acute migraine has been clearly established in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (CitationVisser et al 1996; CitationGijsman et al 1997; CitationGoldstein et al 1998; CitationTeall et al 1998; CitationTfelt-Hansen et al 1998; CitationAhrens et al 1999; CitationBomhof et al 1999; CitationPascual et al 2000; CitationKolodny et al 2004). A meta-analysis of 7 phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in which a total of 4814 patients received treatment for at least 1 migraine attack demonstrated that rizatriptan 10 mg was significantly more effective than placebo at 2 hours on measures of pain relief, pain-free status, nausea, photophobia, phonophobia, and functional disability (p < 0.001 for all comparisons) (CitationFerrari et al 2001). Furthermore, compared with placebo recipients, significantly more patients taking rizatriptan 10 mg had sustained pain relief (18% vs 37%, respectively, p < 0.001) and pain-free status (7% vs 25%, p < 0.001) over 24 hours. The results of these trials have been further confirmed in a large open-label, uncontrolled study (CitationGöbel et al 2001).

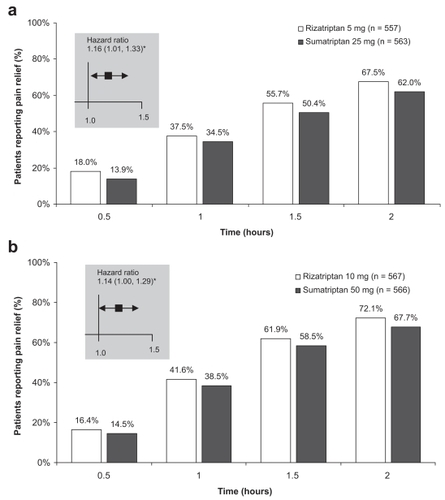

In randomized comparative studies, rizatriptan 10 mg was at least as effective as, or superior to, oral sumatriptan 50 or 100 mg (CitationVisser et al 1996; CitationGoldstein et al 1998; CitationTfelt-Hansen et al 1998; CitationKolodny et al 2004), zolmitriptan 2.5 mg (CitationPascual et al 2000), naratriptan 2.5 mg (CitationBomhof et al 1999), and ergotamine–caffeine 2 mg/200 mg (CitationChristie et al 2003) for a number of efficacy parameters, including headache relief and pain-free status at 2 hours, functional improvement at 2 hours, and time to headache–pain relief (, ). The proportion of patients experiencing headache recurrence was generally similar between patients taking rizatriptan and those taking comparator treatments. However, statistical analyses of this endpoint are usually not performed because recurrence is conditional on initial headache relief and confounded by the use of additional headache–pain medication, thus making interpretation of recurrence rates difficult.

Figure 1 Patients reporting pain relief at time points up to 2 hours following dosing with rizatriptan or sumatriptan in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study (CitationGoldstein et al 1998). Adults with at least a 6-month history of migraine with or without aura were randomized to treat 2 sequential migraine attacks of moderate to severe intensity separated by at least 5 days. Treatment sequences included (a) rizatriptan 5 mg followed by sumatriptan 25 mg or vice versa, (b) rizatriptan 10 mg followed by sumatriptan 50 mg or vice versa, or placebo followed by placebo (data not shown). Hazard ratios for time to pain relief indicate that patients receiving rizatriptan were significantly more likely to achieve pain relief during the 2-hour period than patients receiving sumatriptan. *p < 0.05. Reproduced from CitationGoldstein J, Ryan R, Jiang K, et al. 1998. Crossover comparison of rizatriptan 5 mg and 10 mg vs sumatriptan 25 mg and 50 mg in migraine. Rizatriptan Protocol 046 Study Group. Headache, 38:737–47. Copyright © 1998, with permission from Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Table 1 Comparative efficacy of rizatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine in randomized, double-blind, comparative studies

Analyses of data from several of the above-mentioned comparator studies (CitationTfelt-Hansen et al 1998; CitationGoldstein et al 1998; CitationBomhof et al 1999; CitationPascual et al 2000; CitationKolodny et al 2004) have confirmed the significantly greater efficacy of rizatriptan 10 mg compared with oral sumatriptan 25, 50, or 100 mg, naratriptan 2.5 mg, and zolmitriptan 2.5 mg for stringent efficacy measures (pain-free response at 2 hours, symptom-free response at 2 hours, and 24-hour sustained pain-free response) (CitationAdelman et al 2001), ability to functional normally at 2 hours (CitationBussone et al 2002), and freedom from nausea at 2 hours (sumatriptan and naratriptan) (Lipton, CitationPascual, et al 2001) ().

Table 2 Efficacy of rizatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine in retrospective analyses of comparative studies

Open-label trials have also shown benefits with rizatriptan 10 mg wafer vs oral sumatriptan 50 mg (CitationPascual et al 2001; CitationLoder et al 2001), almotriptan 12.5 mg (CitationLeira et al 2003), and zolmitriptan 5 mg (CitationMathew et al 2000), on efficacy measures such as greater headache relief and/or freedom from pain at 2 hours (vs sumatriptan and zolmitriptan), faster time to headache relief and pain-free status (vs sumatriptan) and reductions in number of triptan doses needed for migraine (vs almotriptan). A small single-blind, single-center, multiple-attack study comparing rizatriptan 10 mg, sumatriptan 100 mg, almotriptan 12.5 mg, zolmitriptan 2.5 mg, and eletriptan 40 mg, reported relatively homogeneous results overall, but superior efficacy with rizatriptan with respect to pain-free response at 2 hours (vs sumatriptan and almotriptan) and sustained pain-free response (vs sumatriptan) (CitationVollono et al 2005). The authors considered rizatriptan to have the best performance of the triptans evaluated but concluded that, owing to the unpredictability of responsiveness to individual triptans, selection of an “ideal triptan” may require a process of trial and error in each patient (CitationVollono et al 2005).

Patients treated with rizatriptan 10-mg tablet or wafer in a typical patient care setting reported better treatment outcomes compared with their prior migraine treatment experiences (primarily triptans, opiates and barbiturates, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), in terms of speed of pain relief (18% and 23% of patients taking rizatriptan tablet or wafer, respectively, reported onset of pain relief within 30 minutes vs 16% for comparator), and 2-hour efficacy endpoints including headache response (66% and 67% vs 37%), pain-free status (31% for both rizatriptan formulations vs 12%), freedom from migraine-associated symptoms (52% and 54% vs 35% largely symptom-free), and ability to resume normal activities (50% and 51% vs 31%) (CitationJamieson et al 2003). Similarly, an open-label, 2-attack study showed that among patients with functional disability at the start of a migraine attack, more patients reported a return to normal function 2 hours after treatment with rizatriptan 10-mg wafer than after treatment of the preceding attack with their usual nontriptan therapy (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics, or ergot derivatives, used alone or in combination) (48% vs 19%, respectively; p < 0.001) (CitationPascual et al 2005). After adjusting for confounding factors, rizatriptan was twice as likely to return patients to normal function compared with their usual nontriptan therapy (hazard ratio 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.92–2.25; p < 0.001), and the speed of return to normal function was significantly greater with rizatriptan therapy (p < 0.001) (CitationPascual et al 2005).

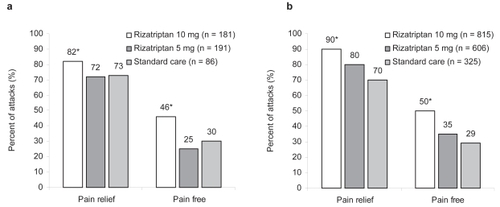

Long-term studies (up to 6 months or 1 year) of acute treatment with rizatriptan tablets (CitationBlock et al 1998) or wafers (CitationCady et al 2001) for multiple attacks showed that rizatriptan 10 mg was superior to rizatriptan 5 mg or “standard care” in terms of pain relief and pain-free status at 2 hours after dosing (). Headache relief rates were consistently maintained over the duration of the studies, with no apparent change in response over time. Importantly, there was no evidence of tolerance to the therapeutic effects of rizatriptan after up to 1 year of treatment (CitationBlock et al 1998). Rizatriptan also demonstrated consistent within-patient efficacy over multiple migraine attacks (CitationKramer et al 1998; CitationDahlof et al 2000).

Figure 2 Median percent of migraine attacks in which patients achieved pain relief or pain-free status 2 hours after dosing. (a) Results in patients enrolled in an open-label, randomized, 6-month extension study who treated at least 1 moderate or severe migraine attack with rizatriptan 5-mg wafers (median of 16 attacks treated), rizatriptan 10-mg wafers (median 13 attacks treated), or standard care (primarily sumatriptan) (median 14 attacks treated). (b) Results in patients enrolled in a 12-month, randomized extension study who treated at least 1 migraine with rizatriptan 5-mg tablets (median of 14 attacks treated), rizatriptan 10-mg tablets (median 21 attacks treated), or standard care (primarily nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) (median 19 attacks treated). *p < 0.05 vs rizatriptan 5 mg and vs standard care. reproduced from CitationCady R, Crawford G, Ahrens S, et al. 2001. Long-term efficacy and tolerability of rizatriptan wafers in migraine. Medscape General Medicine, 3(4): http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408137 © 2001 Medscape; reproduced from CitationBlock GA, Goldstein J, Polis A, et al. 1998. Efficacy and safety of rizatriptan vs standard care during long-term treatment for migraine. Rizatriptan Multicenter Study Groups. Headache, 38:764–71. Copyright © 1998, with permission from Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Quality of life benefits, as measured by the 24-hour Migraine Quality of Life Questionnaire (CitationSantanello et al 1995), have also been reported with rizatriptan treatment. In randomized controlled trials, rizatriptan 10 mg was associated with significantly better migraine-specific quality of life than placebo (p = 0.005) (CitationSantanello et al 1997), and provided improvements in 24-hour quality of life relative to baseline similar to those achieved with oral sumatriptan 25, 50, or 100 mg (CitationGoldstein et al 1998), zolmitriptan 2.5 mg (CitationPascual et al 2000), and naratriptan 2.5 mg (CitationBomhof et al 1999). One study found that rizatriptan 10 mg was superior to rizatriptan 5 mg in this regard (p ≤ 0.001) (CitationSantanello et al 1997).

Rizatriptan has demonstrated efficacy in special patient groups. In a retrospective analyses of data from a subgroup of women with menstrual migraine from 2 randomized placebo-controlled trials, rizatriptan (5 or 10 mg) was significantly more effective than placebo in achieving pain relief and pain-free status at 2 hours (p < 0.05 for both endpoints) (CitationSilberstein et al 2000). Results from this and another retrospective analysis of data from a long-term (up to 6 months) extension study suggest that rizatriptan has similar efficacy in patients with menstrual migraine to that observed in patients with nonmenstrual migraine (CitationSilberstein et al 2002). Rizatriptan 5 mg tablets or wafers were more effective in achieving 2-hour pain relief and pain-free status than standard care (primarily ibuprofen, sumatriptan, zolmitriptan, and aspirin–acetaminophen–caffeine) in adolescents aged 12–17 years, based on pooled data from 2 long-term, open-label studies (CitationVisser et al 2004). In 2 randomized, double-blind, single-attack studies in adolescent patients, rizatriptan 5 mg tablets were not significantly different from placebo for pain relief or freedom from pain at 2 hours (CitationWinner et al 2002; CitationVisser et al 2004); however, there were high placebo response rates in both trials (eg, 2-hour pain relief rates with rizatriptan vs placebo were 66% vs 56% (CitationWinner et al 2002) and 68% vs 69% (CitationVisser et al 2004), respectively).

In most clinical trials rizatriptan was generally administered to patients with moderate-to-severe headaches; however, rizatriptan has also shown efficacy when given for mild pain in the early stages of a migraine attack (CitationMathew et al 2004).

A meta-analysis of results from 53 studies of oral triptans in the treatment of migraine showed that rizatriptan 10 mg appeared to have greater intra-patient consistency for 2-hour headache response and pain-free status over 3 migraine attacks than other triptan dosages evaluated (sumatriptan 25–100 mg, naratriptan 2.5 mg, eletriptan 20–80 mg, and almotriptan 12.5 mg) (CitationFerrari et al 2002). The analysis indicated that rizatriptan 10 mg (along with eletriptan 80 mg and almotriptan 12.5 mg) was one of three triptans most likely to be associated with consistent treatment success, particularly when rapid and consistent relief of pain was required (CitationFerrari et al 2002).

Tolerability and patient acceptability

Rizatriptan was generally well tolerated in the aforementioned randomized, placebo-controlled studies. The frequency of adverse events with rizatriptan appears to be dose-related (CitationVisser et al 1996; CitationFerrari et al 2001). In a summary of adverse event data from 7 randomized, placebo-controlled studies of rizatriptan for the acute treatment of migraine attack, specific adverse events with an incidence of 5% or more in patients receiving placebo (n = 1260), rizatriptan 5 mg (n = 1486), or rizatriptan 10 mg (n = 2068) were dizziness (4%, 6%, and 9%, respectively), somnolence (4%, 5%, and 8%), nausea (4%, 5%, and 6%), and asthenia–fatigue (2%, 3%, and 5%) (CitationFerrari et al 2001). Similarly, the most common adverse events in patients taking rizatriptan 5- or 10-mg tablet or wafer in comparative clinical trials included dizziness (5%–11% of patients across clinical trials), somnolence (4%–10%), asthenia–fatigue (2%–8%), dry mouth (2%–7%), nausea (2%–6%), and chest pain (1%–4%); these events were predominantly transient and mild or moderate in intensity (CitationVisser et al 1996; CitationGoldstein et al 1998; CitationTfelt-Hansen et al 1998; CitationBomhof et al 1999; CitationPascual et al 2000; CitationChristie et al 2003; CitationKolodny et al 2004). In comparator studies, the overall incidence of drug-related adverse events in patients receiving rizatriptan 5- or 10-mg tablet or wafer ranged from 23% to 37%, compared with sumatriptan 25, 50, or 100 mg (28%–41%), zolmitriptan 2.5 mg (28%), naratriptan 2.5 mg (19%), and ergotamine 2 mg–caffeine 200 mg (23%) (CitationBianchi et al 1989; CitationGoldstein et al 1998; CitationTfelt-Hansen et al 1998; CitationBomhof et al 1999; CitationChristie et al 2003; CitationKolodny et al 2004). One study reported a significantly lower adverse event rate in patients receiving rizatriptan 5 and 10 mg vs sumatriptan 100 mg (27% and 33%, respectively, vs 41%; p < 0.05) (CitationTfelt-Hansen et al 1998). Rizatriptan 5-mg tablets and wafers were also well tolerated in adolescents (CitationWinner et al 2002; CitationVisser et al 2004). Most studies reported no serious drug-related adverse events, and very few patients discontinued due to adverse events.

In a large, open, noncomparative study involving 33147 patients receiving treatment with rizatriptan 10 mg in a clinical setting for up to 3 migraine attacks, repeated administration of rizatriptan was well tolerated, with very few adverse events reported (CitationGöbel et al 2001). In this study, 0.9% of patients experienced 1 or more adverse events, the most frequent of which were dizziness (0.2%) and weakness–fatigue (0.2%). A total of 157 patients discontinued rizatriptan owing to an unwanted drug effect, representing 6.3% of all patients who discontinued rizatriptan for any reason and 0.5% of patients enrolled on the study. Fewer than 4.5% of patients taking rizatriptan 5 or 10 mg withdrew because of adverse events in long-term studies of rizatriptan treatment for multiple migraine attacks (CitationBlock et al 1998; CitationCady et al 2001).

In the randomized, double-blind, comparative trials, rizatriptan 10 mg was associated with a higher degree of patient satisfaction with medication compared with sumatriptan 50 mg (mean satisfaction on a scale from 1 “completely satisfied; couldn’t be better” to 7 “completely dissatisfied; couldn’t be worse”: 3.28 vs 3.56 at 2 hours and 3.06 vs 3.39 at 4 hours; p < 0.05 both comparisons) (CitationGoldstein et al 1998), zolmitriptan 2.5 mg (mean 3.38 vs 3.67 at 2 hours; p = 0.038) (CitationPascual et al 2000), naratriptan 2.5 mg (mean 3.55 vs 4.21 at 2 hours; p < 0.001) (CitationBomhof et al 1999), and ergotamine 2 mg–caffeine 200 mg (43.8% vs 21.6% of patients completely satisfied or very satisfied at 2 hours; p ≤ 0.001) (CitationChristie et al 2003).

In a randomized, open-label, crossover trial designed to compare preference for rizatriptan 10-mg wafers vs sumatriptan 50-mg tablets, significantly more patients preferred rizatriptan than preferred sumatriptan (64.3% vs 35.7%; p ≤ 0.001) (CitationPascual et al 2001). The most common reasons for rizatriptan treatment preference were faster relief of headache pain (46.9% of patients), ease of use (8.2%), and fewer side-effects (6.1%). Similar results were seen in a second trial of similar design, with 57% of patients expressing a preference for rizatriptan 10-mg wafers compared with 43% of patients who preferred sumatriptan 50-mg tablets (p = 0.009) (CitationLoder et al 2001). Among those patients with a stated preference, the most important reasons were faster pain relief (51% of patients), the ability to take the medication regardless of patient location (8%; only reported for rizatriptan wafer), and the ability to return to normal activities quicker (7%). It is possible that treatment choice could have been influenced by the ease of use of the rizatriptan wafer formulation in these 2 studies. However, a relatively small percentage of patients reported this as the reason for treatment preference, and results of a separate retrospective nonblinded study in 367 patients showed that a similar number of patients preferred the 10-mg wafer (n = 188) and 10-mg tablet (n = 179) rizatriptan formulations (CitationAdelman et al 2000), suggesting that formulation was probably not the key factor.

A greater proportion of patients preferred rizatriptan 10-mg tablets than preferred ergotamine 1-mg–caffeine 100-mg tablets in a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial (69.9% vs 30.1% of 319 patients expressing a preference, respectively; p ≤ 0.001), with faster relief of headache cited by the majority of these patients (67.3% vs 54.2%, respectively) as the most important reason for preference (CitationChristie et al 2003).

Similarly, among patients who reported a treatment preference in a prospective, open-label, 2-attack study, more patients preferred rizatriptan 10-mg wafers than preferred their usual nontriptan therapy (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, analgesics, or ergot derivatives, used alone or in combination) (78.8% vs 21.2%, respectively; p < 0.001). Overall, the most common reasons cited for preference of either treatment were faster relief of headache pain and faster return to normal function (CitationPascual et al 2005).

The quality of life benefits afforded by rizatriptan, as mentioned above (CitationSantanello et al 1997; CitationGoldstein et al 1998; CitationBomhof et al 1999; CitationPascual et al 2000), are consistent with the favorable efficacy and tolerability profile of the agent.

Patient support and disease management programs

The goals of migraine management are to treat attacks rapidly and consistently without recurrence, restore the patient’s ability to function, minimize the use of rescue medications, optimize self-care and subsequent resource use, be cost effective, and have minimal or no adverse events (CitationSilberstein and for the US Headache Consortium 2000).

CitationBritish Association for the Study of Headache 2004 guidelines recommend a stepwise treatment approach as a means of achieving individualized therapy, starting patients on the safest and cheapest agents with known efficacy (CitationBASH 2004). Treatment steps in ascending order are (i) a simple oral analgesic (eg, aspirin) with or without an antiemetic, (ii) a parenteral analgesic (eg, diclofenac) with or without an antiemetic, and (iii) a migraine-specific agent (eg, triptan). Patients should start on the first step, with treatment failure on 3 occasions being the suggested criterion for progression from one step to the next. The guidelines note that different treatment steps may be used in individual patients who experience attacks of different types or severities. The American Academy of Family Physicians and American College of Physicians–American Society of Internal Medicine (AAFP/ACP–ASIM) also recommend a stepwise treatment approach (CitationSnow et al 2002).

In contrast, United States Headache Consortium 2000 guidelines advocate stratified treatment according to the severity of an individual migraine attack (CitationSilberstein and for the US Headache Consortium 2000). Migraine-specific agents (eg, triptans) are recommended for the initial acute treatment of moderate-to-severe migraine where there are no contraindications for their use. Triptans are also considered appropriate for patients with mild-to-moderate headaches that respond poorly to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or combinations such as aspirin plus caffeine (CitationSilberstein and for the US Headache Consortium 2000). The relative benefits of stepwise and stratified treatment, and the place of triptans in initial migraine therapy, remain a matter for debate. However, there is evidence that stratified treatment provides more effective headache relief for patients with moderate-to-severe migraine-related disability than stepwise strategies used within or between migraine attacks (CitationLipton et al 2000).

While triptans are unlikely to cause substantial coronary vasoconstriction in patients with relatively healthy coronary arteries, their effects may be less predictable in patients with coronary artery disease; therefore, triptans are contraindicated in patients with ischemic heart disease, uncontrolled hypertension, a history of coronary vasospasm, and patients at high risk of asymptomatic coronary artery disease (CitationMartin and Goldstein 2005). Concerns about the cardiovascular safety of the triptans led to an evaluation of triptan-associated cardiovascular risk by the Triptan Cardiovascular Safety Expert Panel of the American Headache Society, and a consensus statement arising from this evaluation concluded that triptans can be prescribed with confidence in patients with low risk of coronary artery disease (CitationDodick et al 2004).

Patients report greater satisfaction with migraine-specific triptan therapy than with analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or ergot derivatives (CitationCeballos Hernansanz et al 2003). British Association for the Study of Headache guidelines state that among the triptans, rizatriptan 10-mg tablet or wafer formulations are an appropriate choice for patients who require stronger oral treatment than sumatriptan (although, due to the pharmacological interaction described above [see pharmacokinetics section], patients receiving prophylactic propranolol should take rizatriptan 5 mg) (CitationBASH 2004). United States Headache Consortium guidelines (CitationSilberstein and for the US Headache Consortium 2000) make no recommendations as to which triptan should be selected. However, consideration should be given to those features considered by patients and physicians as being important in a migraine treatment. Research has shown that although a variety of attributes are desirable, rapid onset of complete pain relief is considered particularly important both by clinicians and patients (CitationLipton et al 2002). In a survey of US primary care physicians, rapid achievement of pain-free and sustained pain-free status were considered the most important efficacy attributes of triptan treatment (CitationCutrer et al 2004).

The TRIPSTAR project was developed to help physicians select oral triptans to best match patient needs by combining data on patient- and physician-reported treatment preferences with results from the aforementioned meta-analysis of triptan clinical trial data (see efficacy section) (CitationLipton et al 2005). When the data from the meta-analysis were evaluated using a Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to the Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) multi-attribute decision model, which considers attributes of the triptans weighted according to patient- and physician-reported treatment preferences, rizatriptan, along with almotriptan and eletriptan, was one of the closest available treatments to the hypothetical “ideal” triptan (defined as the best achievable with current technology) (CitationLipton et al 2005). It is interesting to note that the superiority of rizatriptan, almotriptan, and eletriptan relative to sumatriptan, naratriptan, and zolmitriptan in the above analysis was supported by a separate analysis using a TOPSIS model that considered all possible treatment attribute weightings, rather than importance weights determined in a particular study (CitationFerrari et al 2005).

The potential economic benefits of rizatriptan therapy may also be taken into account when selecting from among the oral triptans. An open-label workplace study in 259 Spanish migraineurs showed that treatment with rizatriptan for 3 months led to significant reductions in the use of medical services, absenteeism, and loss of productivity, as well as improved quality of life compared with the 3 months before starting rizatriptan (CitationLáinez et al 2005). Similarly, a recent analysis determined that substantial productivity costs of migraine to the US employer could be significantly reduced if rizatriptan were used instead of patients’ existing therapies (CitationGerth et al 2004). Moreover, a US cost-effectiveness analysis performed from a societal perspective showed that rizatriptan was more cost-effective in the treatment of acute migraine than sumatriptan or ergotamine–caffeine, reflecting both reduced costs and greater effectiveness (as measured by quality-adjusted life-years gained) (CitationZhang and Hay 2005). In a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of single-dose oral triptans, rizatriptan 10 mg had the most advantageous cost-effectiveness ratio vs other triptans (almotriptan, eletriptan, frovatriptan, naratriptan, zolmitriptan, and sumatriptan) when results were compared using drug cost data from the US, the UK, Canada, Germany, Italy, and The Netherlands, although the levels of statistical significance vs comparators varied between countries (CitationBelsey 2004).

Conclusion

According to current guidelines advocating stepwise or stratified treatment approaches, triptans are recommended for the acute treatment of migraine unlikely to respond to less effective therapy. A number of triptans are available; however, rizatriptan has several advantages over other members of its class (). Rizatriptan reaches maximum plasma concentrations quickly, with a shorter tmax than other available triptans, and produces rapid onset of pain relief. This may prove advantageous in the early treatment of migraine, allowing rapid relief of mild pain before an attack becomes moderate to severe. Comparative clinical trials have shown that for the acute treatment of migraine rizatriptan is at least as effective as, or superior to, other oral migraine-specific agents. Rizatriptan has demonstrated efficacy over the long term (up to 12 months) in the treatment of multiple migraine attacks, and appears to have more consistent efficacy across multiple attacks than other triptans. Rizatriptan is generally well tolerated, with an overall incidence of adverse events and quality of life benefits similar to other triptans. It is associated with a higher degree of patient satisfaction than other migraine-specific agents, with rapid pain relief, ease of use (wafer formulation), and tolerability being important reasons for patient preference. Multi-attribute decision models incorporating efficacy data and weighted clinical attributes identify rizatriptan as one of three triptans closest to a hypothetical ideal. In conclusion, rizatriptan is a well-established, effective, and well-tolerated agent for the acute treatment of migraine.

Table 3 Clinical summary of rizatriptan in the treatment of migraine

Disclosures

Professor Miguel Láinez has received grant/research support from, has been a consultant/scientific advisor for, or has received honoraria for oral presentations from Allergan, Almirall Prodesfarma, Böhringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Elan Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Cilag, Johnson & Johnson, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi-Synthelabo.

References

- AdelmanJULiptonRBFerrariMD2001Comparison of rizatriptan and other triptans on stringent measures of efficacyNeurology5713778311673575

- AdelmanJUMannixLKVon SeggernRL2000Rizatriptan tablet vs wafer: patient preferenceHeadache40371210849030

- AhrensSPFarmerMVWilliamsDL1999Efficacy and safety of rizatriptan wafer for the acute treatment of migraine. Rizatriptan Wafer Protocol 049 Study GroupCephalalgia195253010403069

- BelseyJD2004Cost effectiveness of oral triptan therapy: a trans-national comparison based on a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsCurr Med Res Opin206596915140331

- BergJStovnerLJ2005Cost of migraine and other headaches in EuropeEur J Neurol12Suppl 1596215877781

- BianchiGPassoniAGriffiniPL1989Effects of a new calcium antagonist, Rec 15/2375, on cardiac contractility of conscious rabbitsPharmacol Res211932002748506

- BlockGAGoldsteinJPolisA1998Efficacy and safety of rizatriptan vs standard care during long-term treatment for migraine. Rizatriptan Multicenter Study GroupsHeadache387647111284464

- BomhofMPazJLeggN1999Comparison of rizatriptan 10 mg vs naratriptan 2.5 mg in migraineEur Neurol42173910529545

- [BASH] British Association for the Study of Headache2004Guidelines for all doctors in the diagnosis and management of migraine and tension-type headache2nd ed [online] Accessed 19 September 2005 URL: http://www.bash.org.uk/

- BussoneGD’AmicoDMcCarrollKA2002Restoring migraine sufferers’ ability to function normally: a comparison of rizatriptan and other triptans in randomized trialsEur Neurol48172712373035

- CadyRCrawfordGAhrensS2001Long-term efficacy and tolerability of rizatriptan wafers in migraine [online]Med Gen Med34 URL: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408137

- Ceballos HernansanzMASanchezRRCanoOrg2003Migraine treatment patterns and patient satisfaction with prior therapy: a substudy of a multicenter trial of rizatriptan effectivenessClin Ther2520536912946550

- ChengHPolvinoWJSciberrasD1996Pharmacokinetics and food interaction of MK-462 in healthy malesBiopharm Drug Dispos1717248991488

- ChristieSGobelHMateosV2003Crossover comparison of efficacy and preference for rizatriptan 10 mg vs ergotamine/caffeine in migraineEur Neurol4920912464714

- CumberbatchMJHillRGHargreavesRJ1997Rizatriptan has central antinociceptive effects against durally evoked responsesEur J Pharmacol32837409203565

- CutlerNRJheeSSMajumdarAK1999Pharmacokinetics of rizatriptan tablets during and between migraine attacksHeadache39264915613223

- CutrerFMGoadsbyPJFerrariMD2004Priorities for triptan treatment attributes and the implications for selecting an oral triptan for acute migraine: a study of US primary care physicians (the TRIPSTAR Project)Clin Ther2615334515531016

- DahlofCGLiptonRBMcCarrollKA2000Within-patient consistency of response of rizatriptan for treating migraineNeurology551511611094106

- DodickDLiptonRBMartinV2004Consensus statement: cardiovascular safety profile of triptans (5-HT agonists) in the acute treatment of migraineHeadache444142515147249

- FerrariMDGoadsbyPJLiptonRB2005The use of multiattribute decision models in evaluating triptan treatment options in migraineJ Neurol25210263215761676

- FerrariMDGoadsbyPJRoonKI2002Triptans (serotonin, 5-HT1B/1D agonists) in migraine: detailed results and methods of a meta-analysis of 53 trialsCephalalgia226335812383060

- FerrariMDLoderEMcCarrollKA2001Meta-analysis of rizatriptan efficacy in randomized controlled clinical trialsCephalalgia211293611422095

- GerthWCSarmaSHuXH2004Productivity cost benefit to employers of treating migraine with rizatriptan: a specific worksite analysis and modelJ Occup Environ Med46485414724478

- GijsmanHKramerMSSargentJ1997Double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding study of rizatriptan (MK-462) in the acute treatment of migraineCephalalgia17647519350384

- GoadsbyPJHargreavesRJ2000Mechanisms of action of serotonin 5-HT1B/D agonists: insights into migraine pathophysiology using rizatriptanNeurology55S81411089513

- GoadsbyPJLiptonRBFerrariMD2002Migraine – current understanding and treatmentN Engl J Med3462577011807151

- GöbelHHeinzeAHeinze-KuhnK2001Efficacy and tolerability of rizatriptan 10 mg in migraine: experience with 70527 patient episodesHeadache412647011264686

- GoldbergMRLeeYVyasKP2000Rizatriptan, a novel 5-HT1B/1D agonist for migraine: single- and multiple-dose tolerability and pharmacokinetics in healthy subjectsJ Clin Pharmacol40748310631625

- GoldbergMRSciberrasDDe SmetM2001Influence of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists on the pharmacokinetics of rizatriptan, a 5-HT1B/1D agonist: differential effects of propranolol, nadolol and metoprololBr J Clin Pharmacol52697611453892

- GoldsteinJRyanRJiangK1998Crossover comparison of rizatriptan 5 mg and 10 mg vs sumatriptan 25 mg and 50 mg in migraine. Rizatriptan Protocol 046 Study GroupHeadache387374711284462

- GoriSMorelliNBelliniG2005Rizatriptan does not change cerebral blood flow velocity during migraine attacksBrain Res Bull6529730015811594

- [HCS] Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society2004The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edCephalalgia24Suppl 1916014979299

- HuXHMarksonLELiptonRB1999Burden of migraine in the United States: disability and economic costsArch Intern Med159813810219926

- JamiesonDCutrerFMGoldsteinJ2003Real-world experiences in migraine therapy with rizatriptanHeadache432233012603640

- KolodnyAPolisABattistiWP2004Comparison of rizatriptan 5 mg and 10 mg tablets and sumatriptan 25 mg and 50 mg tabletsCephalalgia24540615196296

- KramerMSMatzura-WolfeDPolisA1998A placebo-controlled crossover study of rizatriptan in the treatment of multiple migraine attacks. Rizatriptan Multiple Attack Study GroupNeurology51773819748025

- LáinezMJLopezAPascualAM2005Effects on productivity and quality of life of rizatriptan for acute migraine: a workplace studyHeadache458839015985105

- LeeYConroyJAStepanavageME1999Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of oral rizatriptan in healthy male and female volunteersBr J Clin Pharmacol47373810233200

- LeiraRDualdeEdel BarrioH2003Almotriptan vs rizatriptan in patients with migraine in SpainHeadache437344112890128

- LiptonRBBigalME2005Migraine: epidemiology, impact, and risk factors for progressionHeadache45Suppl 1S31315833088

- LiptonRBBigalMEKolodnerK2003The family impact of migraine: population-based studies in the USA and UKCephalalgia234294012807522

- LiptonRBCutrerFMGoadsbyPJ2005How treatment priorities influence triptan preferences in clinical practice: perspectives of migraine sufferers, neurologists, and primary care physiciansCurr Med Res Opin214132415811210

- LiptonRBHamelskySWDaynoJM2002What do patients with migraine want from acute migraine treatment?Headache42Suppl 13911966858

- LiptonRBPascualJGoadsbyPJ2001aEffect of rizatriptan and other triptans on the nausea symptom of migraine: a post hoc analysisHeadache417546311576198

- LiptonRBStewartWF1999Acute migraine therapy: do doctors understand what patients with migraine want from therapy?Headache39Suppl 2S206

- LiptonRBStewartWFDiamondS2001bPrevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study IIHeadache416465711554952

- LiptonRBStewartWFStoneAM2000Stratified care vs step care strategies for migraine: the Disability in Strategies of Care (DISC) Study: A randomized trialJAMA284259960511086366

- LoderEBrandesJLSilbersteinS2001Preference comparison of rizatriptan ODT 10-mg and sumatriptan 50-mg tablet in migraineHeadache417455311576197

- LongmoreJHargreavesRJBoulangerCM1997Comparison of the vasoconstrictor properties of the 5-HT1D-receptor agonists rizatriptan (MK-462) and sumatriptan in human isolated coronary artery: outcome of two independent studies using different experimental protocolsFunct Neurol12399127118

- LongmoreJRazzaqueZShawD1998Comparison of the vaso-constrictor effects of rizatriptan and sumatriptan in human isolated cranial arteries: immunohistological demonstration of the involvement of 5-HT1B-receptorsBr J Clin Pharmacol46577829862247

- MaassenVanDenBrinkAReekersMBaxWA1998Coronary side-effect potential of current and prospective antimigraine drugsCirculation9825309665056

- MartinVTGoldsteinJA2005Evaluating the safety and tolerability profile of acute treatments for migraineAm J Med118Suppl 1S3644

- MathewNTKailasamJGentryP2000Treatment of nonresponders to oral sumatriptan with zolmitriptan and rizatriptan: a comparative open trialHeadache40464510849042

- MathewNTKailasamJMeadorsL2004Early treatment of migraine with rizatriptan: a placebo-controlled studyHeadache446697315209688

- Merck & Co Inc2003Maxalt® (rizatriptan benzoate tablets) and Maxalt-MLT® (rizatriptan benzoate orally disintegrating tablets): United States prescribing informationNew Jersey, USAMerck & Co, Inc

- MussonDGBirkKLPanebiancoDL2001Pharmacokinetics of rizatriptan in healthy elderly subjectsInt J Clin Pharmacol Ther394475211680669

- OkazawaHTsuchidaTPaganiM2006Effects of 5-HT(1B/1D) receptor agonist rizatriptan on cerebral blood flow and blood volume in normal circulationJ Cereb Blood Flow Metab2692815944648

- PascualJBussoneGHernandezJF2001Comparison of preference for rizatriptan 10-mg wafer vs sumatriptan 50-mg tablet in migraineEur Neurol452758311385269

- PascualJGarcia-MoncoCRoigC2005Rizatriptan 10-mg wafer vs usual nontriptan therapy for migraine: analysis of return to function and patient preferenceHeadache4511405016178944

- PascualJVegaPDienerHC2000Comparison of rizatriptan 10 mg vs zolmitriptan 2.5 mg in the acute treatment of migraine. Rizatriptan-Zolmitriptan Study GroupCephalalgia204556111037741

- SantanelloNCHartmaierSLEpsteinRS1995Validation of a new quality of life questionnaire for acute migraine headacheHeadache3533077635718

- SantanelloNCPolisABHartmaierSL1997Improvement in migraine-specific quality of life in a clinical trial of rizatriptanCephalalgia17867729453276

- SciberrasDGPolvinoWJGertzBJ1997Initial human experience with MK-462 (rizatriptan): a novel 5-HT1D agonistBr J Clin Pharmacol4349549056052

- SilbersteinSDfor the US Headache Consortium2000Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology557546210993991

- SilbersteinSDMassiouHLe JeunneC2000Rizatriptan in the treatment of menstrual migraineObstet Gynecol962374210908770

- SilbersteinSDMassiouHMcCarrollKA2002Further evaluation of rizatriptan in menstrual migraine: retrospective analysis of long-term dataHeadache429172312390621

- SnowVWeissKWallEM2002Pharmacologic management of acute attacks of migraine and prevention of migraine headacheAnn Intern Med137840912435222

- SperlingBTfelt-HansenP1995Lack of effect of MK-462 on cerebral blood flow in manCephalalgia15Suppl 14206 Abstract p5

- TeallJTuchmanMCutlerN1998Rizatriptan (MAXALT) for the acute treatment of migraine and migraine recurrence. A placebo-controlled, outpatient study. Rizatriptan 022 Study GroupHeadache3828179595867

- Tfelt-HansenPBlockGDahlofC2000aGuidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: second editionCephalalgia207658611167908

- Tfelt-HansenPSaxenaPRDahlofC2000bErgotamine in the acute treatment of migraine: a review and European consensusBrain12391810611116

- Tfelt-HansenPSeidelinKStepanavageM2002The effect of rizatriptan, ergotamine, and their combination on human peripheral arteries: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study in normal subjectsBr J Clin Pharmacol54384412100223

- Tfelt-HansenPTeallJRodriguezF1998Oral rizatriptan vs oral sumatriptan: a direct comparative study in the acute treatment of migraine. Rizatriptan 030 Study GroupHeadache387485511284463

- VisserWHTerwindtGMReinesSA1996Rizatriptan vs sumatriptan in the acute treatment of migraine. A placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Dutch/US Rizatriptan Study GroupArch Neurol53113278912486

- VisserWHWinnerPStrohmaierK2004Rizatriptan 5 mg for the acute treatment of migraine in adolescents: results from a double-blind, single-attack study and two open-label, multiple-attack studiesHeadache44891915447698

- VollonoCCapuanoAMeiD2005Multiple attack study on the available triptans in Italy vs placeboEur J Neurol125576315958097

- VyasKPHalpinRAGeerLA2000Disposition and pharmacokinetics of the antimigraine drug, rizatriptan, in humansDrug Metab Dispos28899510611145

- WilliamsonDJHillRGShepheardSL2001The anti-migraine 5-HT1B/1D agonist rizatriptan inhibits neurogenic dural vasodilation in anaesthetized guinea-pigsBr J Pharmacol13310293411487512

- WilliamsonDJShepheardSLHillRG1997The novel anti-migraine agent rizatriptan inhibits neurogenic dural vasodilation and extravasationEur J Pharmacol3286149203569

- WinnerPLewisDVisserWH2002Rizatriptan 5 mg for the acute treatment of migraine in adolescents: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyHeadache42495512005275

- ZhangLHayJW2005Cost-effectiveness analysis of rizatriptan and sumatriptan vs Cafergot® in the acute treatment of migraineCNS Drugs196354215984898