Abstract

Depression is common in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) and has been identified as the main factor negatively impacting quality of life. It has been reported that depression in PD is under-recognized and under-treated. We report on 90 patients with PD who completed the Geriatric Depression Rating Scale (GDS). Thirteen subjects (14%) scored above 15, the proposed cut-off for diagnosing depression in this illness. Detailed medical record review for these subjects revealed that depression was recognized and treated in only about one-half of the cases. Comparison of mean subscale scores between subjects scoring above and below the cut-off for diagnosis of depression revealed that each of 6 proposed subscales effectively distinguished the two groups. Review of individual items demonstrated that many of the subjects endorsed low energy, regardless of whether they were depressed. This study supports the notion that efforts should be made to educate patients, caregivers and physicians about identifying depression in PD. The routine use of a depression rating scale may facilitate the recognition of depression in this illness.

Introduction

The most commonly recognized clinical features of Parkinson’s disease (PD) involve the motor system and include bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor and postural instability. Psychiatric symptoms are, however, quite common in this illness. About 50% of patients with PD experience depression (CitationDooneif et al 1992). Although major depression occurs in PD, surveys indicate that the majority of depressed PD patients have less severe forms, such as minor depression, dysthymic disorder and subsyndromal symptoms (CitationDooneif et al 1992; CitationLiu et al 1997; CitationStarkstein et al 1998). Recent evidence indicates that depression is the major factor negatively affecting quality of life in PD and that emotional symptoms, including depression, are the main cause of caregiver distress (CitationAarsland et al 1999; CitationKuopio et al 2000; CitationThe Global Parkinson’s Disease Survey 2001). Thus, effective treatment of co-morbid depression has the potential of improving overall function and quality of life for both patients and caregivers.

A recent international survey of patients with PD, caregivers, and physicians found that although depression was the factor most significantly associated with patient quality of life, it is rarely reported by patients to their physicians and may not be recognized by patients themselves (CitationKuopio et al 2000; CitationThe Global Parkinson’s Disease Survey 2001). A study by Shulman et al (2002) demonstrated that neurologists failed to identify the presence of depression in patients with PD more than half of the time. A recently published report by an NIH working group (CitationMarsh et al 2006) highlighted the complexities associated with the diagnosis of depression in PD and pointed out issues that can make the recognition of depression difficult: 1) potential overlap between the signs and symptoms of depression and those of PD itself (eg, decreased facial expression, slowness), 2) the possibility that depression in PD may have an atypical profile of symptoms, and 3) depression of lesser severity (dysthymia, minor depression, subsyndromal depression) is common and may be overlooked in PD. Another possibility for underdiagnosis is that patients and family members (and perhaps physicians) may accept low mood, pessimism, hopelessness, and other symptoms of depression as a normal response to having a neurodegenerative illness rather than as features of an associated mood disorder.

One suggested approach toward better recognition of depression in PD is the routine use of depression rating scales. A self-report scale that has been used in PD patients is the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (CitationYesavage et al 1983; CitationErtan et al 2005). The GDS (CitationYesavage et al 1983) does not emphasize “somatic” symptoms of depression, which may lessen the potential confounds in PD patients, and has, in fact, been shown to be a valid and reliable indicator of depression in PD (CitationErtan et al 2005). Sensitivity and specificity analyses of the 30 item GDS in PD showed that cut-off scores of 9/10 could be used to screen for depression and 14/15 or 15/16 for diagnostic purposes (CitationErtan et al 2005). The GDS was designed to yield a single score and is generally considered a unidimensional scale. However, factor analyses have been performed (using a non-PD sample) (CitationAdams et al 2004), and the following 6 subscales have been proposed: 1) dysphoria (mood), 2) dysphoria (hopelessness), 3) withdrawal/apathy/vigor, 4) anxiety, 5) cognitive, and 6) agitation.

In our previously reported study of mood fluctuations in PD, we noted that subjects with PD achieved significantly higher scores on the GDS compared to age and gender matched healthy controls (Richard et al 2004). In the present study, we report the results of 1) medical record reviews for subjects scoring within the depressed range on the GDS, 2) a comparison between this group and subjects scoring below this level with regard to mean scores on each of the 6 subscales (to determine if some are more useful than others in distinguishing patients with and without depression), and 3) an analysis of the percentages of subjects from each group who endorsed individual rating scale items.

Methods

As part of a diary study of mood fluctuations, 90 consecutive patients with idiopathic PD who were patients from a specialty PD clinic completed the GDS (CitationYesavage et al 1983; CitationErtan et al 2005). Subjects were not selected for depressive symptoms. Study procedures are described in detail in the original article (Richard et al 2004). Subjects were divided into two groups based on their total GDS scores. Subjects with total GDS scores > 15 were considered “depressed”.

An in-depth medical record review was performed for all subjects scoring within the depressed range on the GDS. The groups were then compared with regard to mean scores on each of 6 proposed GDS subscales using the Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric data. For each item, the percentage of subjects answering in the depressed manner was calculated for both groups.

Results

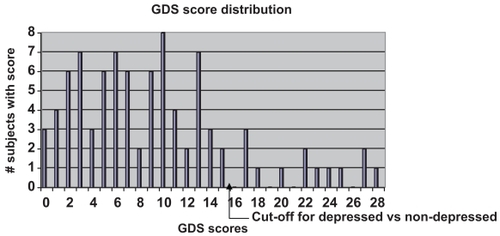

90 PD patients completed the GDS. Subjects were 55% women, with an average age of 66.7 years and a mean Hoehn and Yahr stage of 2.2. GDS scores ranged from 0 to 28, with a mean score of 9.6 (sd = 7.12) and a median score of 9.0. The distribution of the scores is depicted in . Thirteen subjects (14%) scored greater than 15 and comprised the “depressed” group for the purpose of analyses.

Figure 1 The distribution of GDS scores among the 90 subjects. The mean GDS score was 9.6 (sd 7.12) and the median score was 9.0.

Results from a detailed chart review of the 13 patients in the depressed group are summarized in . According to the medical records, 7 of these patients were diagnosed with a mood disorder, 6 of whom were being treated with a medication for depression. We also reviewed the medical records of the 2 subjects with scores of 15 (not included in ), neither of whom had medical record evidence of depression diagnosis or treatment.

Table 1 Characteristics of subjects scoring above 15 on the GDS

Statistical analyses demonstrated that mean scores for each of the 6 subscales were significantly different between the depressed and nondepressed groups (p < 0.001) ().

Table 2 Comparison of mean subscale scores between “depressed” and “non-depressed” groups

The percentages of subjects from each group who responded in the “depressed” manner on each GDS item are outlined in . A minority of patients reported worrying about the past, even among the depressed subjects. On the other hand, most patients reported low energy, regardless of their total GDS Score.

Table 3 Frequency of “depressed” responses for each GDS item

Conclusion

About half of PD patients completing the GDS in our study scored above 9, the cut-off recommended for screening purposes with this depression rating scale which has been deemed valid and reliable in PD (CitationErtan et al 2005; CitationYesavage et al 1983). Although this finding is based on patient self-report and may be biased towards more complicated cases seen in a PD specialty clinic, the observed frequency of depression is similar to previously reported rates in PD (CitationDooneif et al 1992: CitationThe Global Parkinson’s Disease Survey 2001).

Thirteen of the 90 patients (14%) scored above 15, the recommended cut-off score for the diagnosis of depression in PD, also reflecting scores greater than one standard deviation above the mean (9.6 ± 7.1) for our sample. Medical record review revealed that depression was diagnosed and treated in about half of these subjects. These results were consistent with those of other studies suggesting that there is inadequate recognition of depression by both PD patients (CitationKuopio et al 2000; CitationThe Global Parkinson’s Disease Survey 2001) and their physicians (Shulman et al 2002). Our study suggests that it is not just mild depressive symptoms that are under-recognized and untreated. Thus, the relatively mild severity of depression in many cases of PD is not a satisfactory explanation for its under-recognition.

Our analysis of subscale scores revealed that each of the six subscales effectively distinguished patients scoring within the depressed range from those scoring below the cut-off. Review of individual rating scales demonstrated that worrying about the past (guilt, self-reproach) is relatively uncommon among PD patients whether depressed or not. Diminished energy is a common complaint, even among those who do not score within the depressed range. These findings are in keeping with the notion that depression in PD may have atypical features (low guilt) (CitationCummings 1992). A possible explanation for why low energy may not be a specific symptom of depression is recent information indicating that fatigue is a common and independent feature of PD (CitationFriedman and Friedman 2001; CitationAlves et al 2004).

The results of this study support the view that efforts are needed to better educate patients, family members and physicians about depression in PD (CitationAarsland et al 1999; CitationKuopio et al 2000; CitationThe Global Parkinson’s Disease Survey 2001). Our study suggests that the routine use of a self-rating depression scale may increase the likelihood of identifying symptoms of depression.

Acknowledgments

Dr Richard’s research has been supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (#1 K23NS02184) and by a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD). We would like to thank Anne Justus for her help with data acquisition and entry and Donna LaDonna with her help preparing the manuscript.

References

- AarslandDLarsenJPKarlsenK1999Mental symptoms in Parkinson’s disease are important contributors to caregiver distressInt J Geriatric Psychiatry1486674

- AdamsKBMattoHCSaundersSConfirmatory factor analysis of the Geriatric Depression ScaleThe Gerontologist20044481882615611218

- AlvesGWentzel-LarsenTLarsenJP2004Is fatigue an independent and persistent symptom in patients with Parkinson’s disease?Neurology6319081115557510

- CummingsJDepression and Parkinson’s disease1992 A reviewAm J Psychiatry149443541372794

- DooneifGMirabelloEBellK1992An estimate of the incidence of depression in idiopathic Parkinson’s diseaseArch Neurol4930571536634

- ErtanFSErtanTKiziltanG2005Reliability and validity of the Geriatric Depression Scale in depression in Parkinson’s diseaseJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry761445716170093

- FriedmanJHFriedmanH2001Fatigue in Parkinson’s disease: a nine year follow-upMov Disord161120211748745

- KuopioAMarttilaRHelleniusH2000The quality of life in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord152162310752569

- LiuC-YWangS-JFuhJ-L1997The correlation of depression with functional activity in Parkinson’s diseaseJ Neurol24449389309555

- MarshLMcDonaldWMCummingsJNINDS/NIMH Work Group on Depression and Parkinson’s Disease2006Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression in Parkinson’s disease: Report of a NINDS/NIMH Work GroupMov Disord211485816211591

- RichardIHFrankSMcDermottM2002The ups and downs of Parkinson’s disease: A prospective study of mood and anxiety fluctuationsCog Behav Neurol172017

- ShulmanLMTabackRLRabinsteinAAWeinerWJNon-recognition of depression and other non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s diseaseParkinsonism Relat Disord8193712039431

- StarksteinSPetraccaGShermerinskiE1998Depression in classic versus akinetic Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord1329339452322

- The Global Parkinson’s Disease Survey (GPDS) Steering Committee2001Factors impacting on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: Results from an international surveyMov Disord176067

- YesavageJABrinkTLRoseTL1983Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary reportJ Psychiatry Res173749