Abstract

Glaucoma disproportionately affects individual of African ancestry. Additionally, racial differences in the optic nerve head have been well described that may alter the vulnerability to intraocular pressure related injury and, in addition, alter the clinical ability to detect the presence of early optic nerve injury. This paper will review the literature describing racial differences in the optic nerve head between individuals of African and European ancestry with regards to the potential effects of these differences on the ability to detect glaucoma in different racial groups and to potential differences in the pathogenesis of glaucomatous injury.

Introduction

The burden from glaucoma disproportionately affects individuals of African ancestry who are at much greater risk of developing glaucoma (CitationSeddon 1991; CitationTielsch et al 1991; CitationSommer et al 1991; CitationSommer 1996) and blindness from glaucoma (CitationJavitt and al 1991). Glaucoma remains the leading cause of irreversible blindness among Blacks, while it is the third leading cause among Whites. The reason for this differential burden is multifactoral and incompletely understood. While, socioeconomic disparity, differences in healthcare access, and differences in both systemic comorbidities and ocular parameters such as corneal thickness all play some role, the hypothesis central to our investigations is that variation in the structure of the optic nerve remains an important and critical factor in the more aggressive disease seen in this at-risk underserved population. This paper will review the literature concerning racial variation in the structure of the optic nerve between Blacks and Whites and the impact these differences may have on diagnosis and follow-up of glaucoma and possible implications for pathogenesis in this at-risk population.

Problems with the definition of race

Medical researchers and clinicians often categorize patients and research subjects by race in order to recognize differences in susceptibility to disease, to determine differing medical needs, and to highlight health disparities (CitationWilliams and Rucker 2000). However, several authors have raised questions as to the validity of racial classification in the strict biologic sense (CitationGoodman 2000). Additionally, the history of the use of the term race, especially with regards to attempts to define race on a genetic basis, is full of examples of misuse in both scientific and political circles (CitationLa Veist 1996). In response to these concerns, ethnicity has been touted as a superior, and perhaps less controversial term. However, cultural distinctions as well as racial ones define ethnicity (CitationHahn and Stroup 1994). Thus ethnicity may be even more ambiguous to define than race (CitationWilliams 1996).

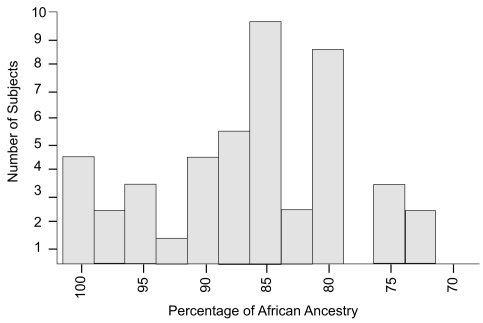

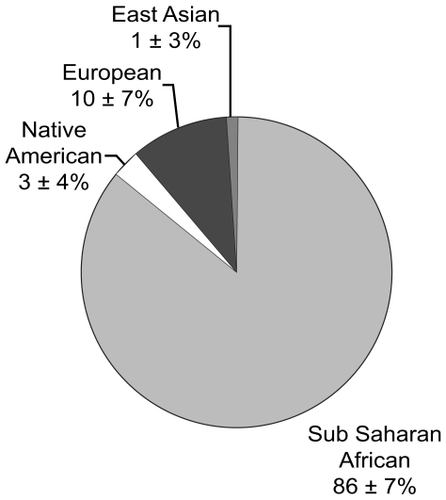

Most of the epidemiologic literature uses self-description to define racial differences. Clearly there are limitations with using this definition and self-described race is a term that represents an amalgam of cultural, geographic, socioeconomic, and biologic characteristics and is at best an incomplete summary of human biodiversity that cannot be interpreted in the strict biologic sense (CitationSommer 2003). However, self-described race has demonstrated dependent and independent associations to glaucoma along with several other ocular and systemic conditions, thus it remains an important and relatively accessible factor (CitationTielsch et al 1991). Several researchers have used more sophisticated genetic methods to describe racial variation using multiple assays of single nucleotide polymorphism haplotypes (SNPs) to develop a profile of genetic admixture (CitationSmith et al 2001; CitationRosenberg et al 2002; CitationGower et al 2003; CitationShriver et al 2003). These admixture profiles correlate highly to the biogeographic structure of human populations and can be used to summarize the genetic ancestry of mixed populations. Initial experience using these techniques with subjects participating in our studies has clearly demonstrated the imprecision of self-describe race to determine ancestral history (). Fortunately, genetic admixture estimates of ancestral origin, generally correlate highly to self-described race, which is much easier to obtain, and thus self-described race is probably an adequate surrogate for molecular biologic testing in many situations (CitationRosenberg et al 2002).

Figure 1a Proportion of African Ancestry as determined from polymorphisms within 178 AIMs for normal self-described black ADAGES participants (n = 45).

Figure 1b Mean (±standard deviation) percentage Ancestry in the four Ancestral Groups determined by polymorphisms within 178 AIMS for normal Self-described black ADAGES participants (n = 45).

While race is a tenuous biologic concept, many researchers consider that the influence of race on the delivery of medical care and clinical science is so strong that information regarding race should still be collected in clinical studies, with the acknowledgment that it is an imprecise and poorly understood measurement (CitationSommer 2003; CitationWilson 2003). We share this view and while the literature supports a significant relationship between self-described race and glaucoma, the causal factors for this association and how it is mediated remains poorly understood. However, we have continued to use self-described race in our research and are of the opinion that this can provide useful information as long as this information is obtained using standardized methodology.

Previously describe racial differences in the optic nerve

Several clinical and histological studies have characterized racial differences in optic disc structure between blacks and whites. Quantitative evaluation of conventional optic disc photography from the Baltimore Eye Survey demonstrated that mean optic disc area was 12% larger in Blacks compared to Whites (CitationVarma et al 1994). Cup area was larger as well. While global rim area was similar in both racial groups, due to the relatively larger optic disc in Blacks, there was a decrease in rim/disc area, indicating that there may be a decrease in rim thickness and nerve fibers relative to disc size in this population. In a smaller study including 200 normal subjects, also using disc photography, Beck and colleagues also demonstrated that there was an increase in cup-to-disc ratio in Blacks relative to Whites (CitationBeck et al 1985). Finally, a post-mortem histological study of 30 White and 30 Black eye donors demonstrated a larger vertical diameter of the optic disc, but not in horizontal diameter in the Black group (CitationQuigley et al 1990).

Optic disc and nerve fiber layer imaging techniques have evolved out of an attempt to acquire quantitative objective topographic information regarding optic disc structure and in-vivo measurements of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in order to improve the ability to detect glaucoma and progressive glaucomatous damage. Current studies evaluating these instruments have previously been performed in predominantly White study populations and have not included adequate numbers of Black subjects to evaluate the role of quantitative optic disc analysis, the parameters that are most predictive of glaucoma, and optimum analysis strategies for detection of glaucoma in this at risk population.

Differences in optic disc structure between Blacks and Whites may have an effect on the ability of optic disc and nerve fiber layer imaging techniques to detect glaucoma. Broadway demonstrated that the discriminating ability of confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (CSLO) varied depending on the phenotype of optic disc damage present (CitationBroadway et al 1998). In addition, CitationIester et al (1997) demonstrated that optic disc area has an effect on the diagnostic precision of the CSLO. This is an important consideration in that one of the primary reported differences in optic disc structure between Blacks and Whites is disc area (CitationVarma et al 1994).

We recently compared the CSLO results between 146 eyes from Black subjects and 97 eyes from White subjects, and found similarly that Blacks had significantly greater optic disc area, cup area and volume, and similar rim area and volume (CitationGirkin et al 2005). Additionally, Black subjects had a deeper optic disc cup than Whites. Following adjustment for racial variation in disc area, there was no significant difference between racial groups other than cup depth, indicating that most of the normal variation in optic disc topography between Blacks and Whites seen with the CSLO is due to differences in disc area except for differences in cup depth (). We hypothesized that those methods that account for disc area should perform similarly across racial groups and the Moorfields classification (CitationWollstein et al 2000), which takes disc area into account, performed with similarly specificity in each racial group in this study.

Table 1 Comparison of structural parameters of the optic disc between African-American and White groups

In an additional conducted study to determine the structural characteristics of the optic disc that are associated with early glaucoma in Blacks and Whites and whether these characteristics differ between these races (CitationGirkin et al 2003), parameters of optic disc topography from 260 eyes from black participants and 193 eyes from white participants were included in the analysis. A staged multivariable logistic regression model was used to calculate the association between glaucoma and cup, rim and disc margin parameters. To account for the effect of differences in optic disc area, this parameter was included in the multivariable model at each level of interaction in constructing the final model. To account for the intercorrelation of eyes within persons, generalized estimating equations were used.

This study found similar racial differences between normal control subjects with CSLO than prior studies using photography. These differences included a larger disc area, cup-to-disc ratio, rim area and cup area in Blacks. Additionally we found several other CSLO parameters that were significantly different in the Black control group including greater cup depth, and a thicker nerve fiber layer measurement.

This study demonstrated racial differences exist in the optic disc structural parameters that are independently predictive of early glaucoma between Blacks and Whites even when accounting for differences in optic disc area. While the most predictive parameter, rim area, was the same for each racial group, the magnitude of association was higher in Whites. Differences in disc area does account for some of these racial differences; however, residual differences still persist. Overall, the summary odds ratios based on the most predictive CSLO parameters demonstrated a lower association with glaucoma in Blacks, even when adjusted for the effect of disc area. These differences in the relationship between optic disc structural and visual functional measures between Black and Whites indicate that topographic features of the optic disc convey different information with regards to assessing the risk of early glaucoma in differing racial groups, which should be considered in the statistical judgment of disease status based on these parameters.

Impact of racial variation of the optic nerve on disease detection

Racial variation on optic nerve structure may have a significant impact on the ability to detect glaucoma by subjective and objective techniques. Larger optic nerves have a larger scleral canal and consequently larger optic cups for the same rim volume and number of retinal nerve fibers. Thus, a larger nerve is more likely to be misconstrued as glaucomatous on casual observations, whereas a smaller nerve with a small degree of glaucomatous cupping may be overlooked as normal.

Differences in optic disc structure between Blacks and Whites may have an effect on the ability of optic disc and nerve fiber layer imaging techniques to detect glaucoma. Broadway demonstrated that the discriminating ability of the CSLO varied depending on the phenotype of optic disc damage present (CitationBroadway et al 1998). In addition, CitationIester et al (1997) demonstrated that optic disc area has an effect on the diagnostic precision of the CSLO. This is an important consideration in that one of the primary reported differences in optic disc structure between Blacks and Whites is disc area (CitationVarma et al 1994).

Our prior studies using the CSLO have also demonstrated that racial variations in optic disc structure had little impact on the ability of structural parameters and discriminant functions to detect glaucomatous visual field defects. However, differences in normative values required race-specific cutoff values to optimize specific detection strategies (CitationDeleon-Ortega et al 2006). The widely used Moorfields regression analysis, which takes in to account disc area, performed similarly across racial groups, but optic disc area had a significant impact on the diagnostic efficacy of this technique with more patients incorrectly diagnosed as glaucomatous who had larger optic nerves, probably reflecting the normative database used to develop this technique (CitationGirkin et al 2006).

Impact of racial variation of the optic nerve on the pathogenesis of glaucoma

Since the biomechanical behavior of any object is determined by its morphology and its material properties, there are potentially important biomechanical implications with the variations in optic disc morphology our group and others have described. While little is currently known regarding the impact of variations in optic disc anatomy and the susceptibility of glaucoma, preliminary computational modeling of the biomechanical behavior of the lamina cribrosa and posterior scleral has suggested that the laminar connective tissue may experience greater intraocular pressure-related stress and strain in idealized eyes with larger optic disc area (CitationBellezza et al 2000). Thus the larger optic nerve found more commonly in patients of African ancestry may experience greater strain at similar levels of pressure. Additionally, the findings of a deeper cup in patients of African ancestry may relate to either a thinner lamina cribrosa or a more posterior insertion of the lamina within the scleral wall (CitationGirkin et al 2005). The impact of these morphologic variations has yet to be explored. The field of biomechanical modeling of the optic nerve connective tissues is rapidly developing and will add to our understanding of the impact of variation in the microarchitecture of the optic nerve on the biomechanical behavior of the critically supportive connective tissue that are important to the development of glaucoma.

Conclusion

While socioeconomic differences, disparities in health care access, and differences in disease awareness, along with several differences in potential systemic risk factors all play a role in the higher prevalence of glaucoma in African-Americans, ocular characteristics (primarily in central corneal thickness and in optic disc structure) may explain the increased risk of glaucoma in this population. As our clinical ability to detect glaucomatous progression improves with the further evolution of ocular imaging and physiologic testing, these ocular differences between Blacks and Whites are important to recognize and evaluate in longitudinal trials, if this new information is to be applied for maximal benefit in this at-risk population. The exact role of these racial differences in nerve structure in the variation in susceptibility to glaucoma remains to be elucidated.

Financial support

NIH grant K23 EY13959-01, Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., and The EyeSight Foundation of Alabama.

References

- BeckRWMessnerDKMuschDC1985Is there a racial difference in physiologic cup size?Ophthalmology9287364022570

- BellezzaAJHartRTBurgoyneCF2000The optic nerve head as a biomechanical structure: initial finite element modelingInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci412991300010967056

- BroadwayDCDranceSMParfittCM1998The ability of scanning laser ophthalmoscopy to identify various glaucomatous optic disk appearancesAm J Ophthalmol1255936049625542

- Deleon-OrtegaJEArthurSNMcgwinGJr2006Discrimination between glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous eyes using quantitative imaging devices and subjective optic nerve head assessmentInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci4733748016877405

- GirkinCADeleon-OrtegaJEXieA2006Comparison of the Moorfields classification using confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and subjective optic disc classification in detecting glaucoma in blacks and whitesOphthalmology1132144916996609

- GirkinCAMcgwinGJrMcNealSF2003Racial differences in the association between optic disc topography and early glaucomaInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci443382712882785

- GirkinCAMcGwinGJrXieA2005Differences in optic disc topography between black and white normal subjectsOphthalmology11233915629817

- GoodmanAH2000Why genes don’t count (for racial differences in health)Am J Public Health90169970211076233

- GowerBAFernandezJRBeasleyTM2003Using genetic admixture to explain racial differences in insulin-related phenotypesDiabetes5210475112663479

- HahnRAStroupDF1994Race and ethnicity in public health surveillance: criteria for the scientific use of social categoriesPublic Health Rep1097158303018

- IesterMMikelbergFSDranceSM1997The effect of optic disc size on diagnostic precision with the Heidelberg retina tomographOphthalmology10454589082287

- JavittJCAlE1991Undertreatment of glaucoma among black AmericansNE J Med325141820

- La VeistTA1996Why we should continue to study race. but do a better job: an essay on race, racism and healthEthn Dis62198882833

- QuigleyHABrownAEMorrisonJD1990The size and shape of the optic disc in normal human eyesArch Ophthalmol1085172297333

- RosenbergNAPritchardJKWeberJL2002Genetic structure of human populationsScience2982381512493913

- SeddonJM1991The differential burden of blindness in the United States [editorial; comment]N Engl J Med325144021922257

- ShriverMDParraEJDiosS2003Skin pigmentation, biogeographical ancestry and admixture mappingHum Genet1123879912579416

- SmithMWLautenbergerJAShinHD2001Markers for mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium in African American and Hispanic populationsAm J Hum Genet6910809411590548

- SommerA1996Glaucoma risk factors observed in the Baltimore Eye SurveyCurr Opin Ophthalmol793810163329

- SommerA2003Epidemiology, ethnicity, race, and riskArch Ophthalmol121119412912700

- SommerATielschJMKatzJ1991Racial differences in the cause-specific prevalence of blindness in east Baltimore [see comments]N Engl J Med3251412171922252

- TielschJMSommerAKatzJ1991Racial variations in the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma. The Baltimore Eye SurveyJAMA266369742056646

- VarmaRTielschJMQuigleyHA1994Race-, age-, gender-, and refractive error-related differences in the normal optic discArch Ophthalmol1121068768053821

- WilliamsDR1996Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status: measurement and methodological issuesInt J Health Serv264835058840198

- WilliamsDRRuckerTD2000Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health careHealth Care Financ Rev21759011481746

- WilsonMR2003The use of “race” for classification in medicine: is it valid?J Glaucoma12293412897572

- WollsteinGGarway-HeathDFFontanaL2000Identifying early glaucomatous changes. Comparison between expert clinical assessment of optic disc photographs and confocal scanning ophthalmoscopyOphthalmology1072272711097609