Abstract

Major advances in the management of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) include an enhanced ability to make an accurate diagnosis and define clinically meaningful prognostic groups, while improving outcome through more effective therapeutic regimens and supportive care. Nevertheless, CLL remains an incurable disorder and new, active agents are needed. Bendamustine, a unique cytotoxic agent with structural similarities to both alkylating agents and antimetabolites, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of CLL and rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In a randomized trial, bendamustine was superior to chlorambucil, with comparable toxicity. Combinations with other active agents including rituximab and lenalidomide are in development. Nevertheless, numerous questions concerning the ideal use of this agent remain to be addressed, including the optimal dose and schedule and mechanisms of resistance. The availability of bendamustine provides another effective treatment option for patients with lymphoproliferative disorders. Rational development of combination regimens will improve the outlook for patients with CLL.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common form of leukemia in the United States (US), with more than 15,000 new cases projected for 2008.Citation1 The median age at diagnosis is 72 years and more than half of patients are diagnosed incidentally at the time of evaluation for other medical issues.Citation1 Whereas some patients do not require treatment at diagnosis and can be managed by watchful waiting, others may need treatment for symptomatic or progressive disease.Citation2 For these patients the aim of therapy is to prolong survival and improve quality of life as there are no curative options. These goals can be achieved by a variety of therapeutic strategies ranging from conventional therapies to experimental treatments.

Traditionally, the most frequently used initial systemic therapies have been chlorambucil or fludarabine. More recently, the availability of effective and well-tolerated monoclonal antibodies has substantially altered the therapeutic approaches to these patients. The two most widely used have been rituximab and alemtuzumab. Rituximab, as a single agent has limited activity in relapsed/refractory CLL; however as an initial treatment, response rates of 51% have been reported.Citation3–Citation6 The efficacy and tolerability of rituximab provided rationale of combining it with other agents. Rituximab, combined with fludarabine alone or with cyclophosphamide (FR or FCR) has been associated with responses in more than 90% of patients, most being complete remissions (CR).Citation7,Citation8 These regimens also appear to improve survival compared to historical controls.Citation7,Citation9 More recently, a randomized study comparing fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) to FCR showed that FCR treated patients had an increased CR (52% vs 27%, p < 0.0001), improved progression-free survival (PFS) (2 year: 76.6% vs 62.3%, p < 0.0001) and a trend towards increased overall survival (OS) (2 year: 91% vs 88%, p 0.18).Citation10 Despite the high response rates with rituximab-based combination therapy, patients invariably relapse and require additional therapies. Moreover, present regimens are associated with significant toxicity, especially in elderly patients.Citation11 As CLL remains incurable, there remains a constant need to improve upon the current treatment options.

One promising drug is bendamustine, a unique alkylating agent, which was first synthesized in the early 1960s in Jena in the former East German Democratic Republic by Ozegowski et alCitation12 For over 30 years, bendamustine was used in the former German Democratic Republic to treat patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), CLL, multiple myeloma (MM), Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and carcinoma of the breast. Following the German reunification, bendamustine was approved in Germany for the treatment of patients with indolent NHL, CLL, MM and breast cancer, and many new studies were initiated aimed at better defining the value of this drug in treating these conditions.

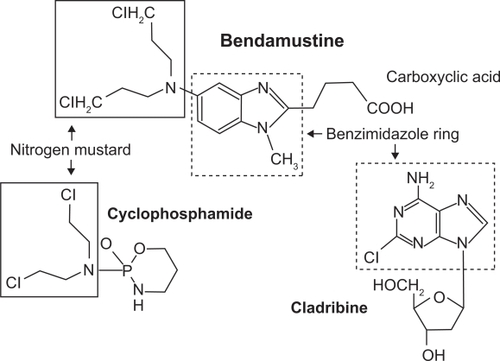

Bendamustine is referred to by the chemical name γ-[1-methyl-5-bis-(β-chloroethyl)-amino-benzimidazolyl-(2)]-butyric acid hydrochloride. The structure of bendamustine consists of a benzamidazole ring with a nitrogen mustard group at position 5 () providing structural similarities to both alkylating agents and antimetabolites.Citation13 Similar to other alkylating agents, bendamustine causes DNA double-strand breaks but these are more extensive and durable than those produced by other alkylating agents.Citation14 Bendamustine has also been shown to work by activating DNA-damage stress response and intrinsic apoptosis, inhibiting mitotic checkpoints, induction of mitotic catastrophe, and activating base excisions DNA repair pathway rather than an alkyltransferase DNA repair mechanism, different from other alkylating agents like cyclophosphamide, melphalan and chlorambucil.Citation13 Bendamustine exhibits incomplete cross-resistance with other alkylating agents (eg, cyclophosphamide, melphalan and carmustine) due to a substance-specific interaction between bendamustine and DNA.Citation14 Moreover, the addition of rituximab in vitro reduces the dose of bendamustine required to induce apoptosis in ex-vivo B-CLL cells.Citation15,Citation16 This observation provided the rationale for the development of clinical studies combining these two agents.Citation17–Citation19

Clinical studies of bendamustine

Several small studies using different dosing schedules provided the initial evidence of clinical activity of bendamustine in CLL ().Citation20–Citation22 These studies reported overall response rates (ORR) between 65% and 93% with complete remission rate (CR) between 7% and 29%.

Table 1 Single-agent clinical trials of bendamustine in CLL

Dose finding studies

Although bendamustine has been used for over 30 years, most of the dosing schedules are empiric, and the optimal dose and schedule remains unknown. Several studies have been conducted to determine the maximal tolerated dose, dose-limiting toxicity and optimal therapeutic dose of bendamustine in patients with CLL ().

Kath et al reported that a 5-day schedule had excessive myelotoxicity with a reported rate of leukopenia (grade III/IV) of 51% resulting in septic death of 13% of patients.Citation22 This study suggested that the 5 day schedule was too toxic for many patients.

The German CLL study group (GCLLSG) conducted a phase I/II study in 16 patients with relapsed or refractory CLL.Citation23 Patients had received a median of 3 prior regimens and 50% had previously received fludarabine. Dose escalation started at 100 mg/m2 intravenously (iv) on days 1 and 2 every 3 to 4 weeks. Six patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) which led to dose de-escalation; 2 at 100 mg/m2, 1 at 90 mg/m2, 2 at 80 mg/m2 and 1 out of 7 at 70 mg/m2. The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) in this study was 70 mg/m2 every 4 weeks. Major toxicities included grade III/IV leukopenia in 50%, and grade III/IV infection in 43% of patients; 2 patients died from atypical pneumonia. Despite the dose de-escalations, the ORR was 58% (9/16), including 7 of 12 patients treated at doses of ≤80 mg/m.2 The median duration of response in patients evaluable for response was 42.7 months and 43.6 months for the responders. Of the patients that were previously treated with fludarabine (n = 8) only those who were not fludarabine refractory responded (n = 4), with 2 CR and 2 partial remissions (PR). Six of the 8 patients without prior fludarabine responded with 1 CR.

Lissitchkov et al conducted a phase I/II study of bendamustine in fludarabine naïve patients with CLL. Dose escalation started at 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks and in the absence of DLT during the first cycle the dose was to be increased by 10 mg/m2 increments.Citation24 The treatment interval had to be prolonged to every 28 days to allow for bone marrow recovery. Six patients experienced DLTs; 1 at 100 mg/m2, 2 at 110 mg/m2, while all 3 patients had DLTs at 120 mg/m2. DLTs included grade III/IV hyperbilirubinemia, grade IV anemia and grade IV thrombocytopenia. Rate of grade III/IV leukopenia was 20%. All 6 patients treated at 100 mg/m2 responded, with 4 CRs and 2 PRs. After a follow up of 15 months only 1 patient had relapsed and the median duration of response of patients with CR was 22 months (range 18–27 months). The recommended dose from this study was 100 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2 every 28 days.

The tolerability of bendamustine varied between these two studies. The MTD of bendamustine in the GCLLSG trial was 70 mg/m2 while Lissitchkov et al recommended a dose of 100 mg/m2.Citation23,Citation24 The different MTDs between these two studies could be explained, in part by the differences in their study population that may have increased the likelihood of myelosuppression and infection in the GCLLSG study. The GCLLSG trial included patients who were elderly with advanced disease who had been heavily pretreated (upto 6 prior therapies), and were resistant to either fludarabine, chlorambucil or both.Citation23 While Lissitchkov et al included patients who were fludarabine naïve and had received an average of 3 prior therapies, explaining in part the better tolerability of bendamustine.Citation24

Randomized trial of single-agent bendamustine in patients with relapsed CLL

Bendamustine has been directly compared with fludarabine in patients with CLL who had relapsed after one prior therapy.Citation25 In this study, fludarabine naïve patients were randomized to either bendamustine (100 mg/m2 d 1–2 q 28 days) or fludarabine (25 mg/m2 d 1–5 q 28 days) until best response or to a maximum of 8 cycles. The primary objective of the study was to determine if progression-free survival (PFS) was comparable between the two treatment arms. Out of a total of 96 patients 89 were eligible for an interim analysis (46 patients assigned to bendamustine and 43 to fludarabine). Baseline characteristics including age, Binet stage, bulky disease, and B-symptoms were equally matched between the groups. Ninety-five percent of patients had received a chlorambucil-based regimen as their initial therapy. About half of the patients received 6 or more cycles in either treatment arm. The ORR was 78% (29% CR) in the bendamustine arm versus 65% (10% CR) in the fludarabine arm. After a median follow up of 2 years, median PFS was 83 weeks versus 63 weeks (HR 0.93, CI 0.59–1.47) with bendamustine and fludarabine, respectively. The bendamustine arm was associated with a slightly higher incidence of hematologic toxicity, but the rate of grade III/IV infections was similar, occurring in 15% of the patients in both the arms. This study suggested that bendamustine can be considered a reasonable alternate to fludarabine. However, confirmation in a larger study is warranted.

Phase III clinical trial in previously untreated patients with CLL

Knauf et al conducted a multicenter study, in which they randomized 319 previously untreated CLL patients to either bendamustine or chlorambucil.Citation26 Bendamustine was administered at 100 mg/m2 iv on 2 consecutive days, while chlorambucil was given at 0.8 mg/kg orally on days 1 and 15. Cycles were repeated every 28 days. Treatment was repeated for a maximum of 6 cycles. Primary endpoints of the study were ORR and PFS. The secondary endpoints were OS and safety.

Median age was 64 years and patients had Binet stage B (70%) or C (30%) disease. Treatment was well tolerated with mean number of cycles administered being 4.8 (SD ± 1.7) with bendamustine and 4.6 (SD ± 1.7) with chlorambucil. Most doses were administered on schedule and dose intensity was maintained in both groups, 86% with bendamustine and 96% with chlorambucil. All 319 patients were evaluable for efficacy analysis, 162 on the bendamustine arm and 157 on the chlorambucil arm. Response rates were superior for bendamustine compared with chlorambucil, ORR 67% versus 30% (p < 0.0001), respectively. After a median follow up of 29.2 months, the median PFS was 21.5 months versus 8.3 months (p < 0.0001), for bendamustine and chlorambucil, respectively. As of the time of the report, there was no difference in overall survival.

Toxicities of bendamustine were predictable and manageable. Grade III/IV neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia were observed more frequently in the bendamustine arm (). Nevertheless, grade III/IV infections were uncommon in both groups (7% versus 4% in bendamustine versus chlorambucil group, respectively). Non-hematologic adverse reactions (any grade) in the bendamustine group that occurred with greater than 15% frequency were pyrexia (24%), nausea (20%), and vomiting (16%). The most frequent adverse reactions leading patients receiving bendamustine to withdraw from the study were hypersensitivity (2%) and pyrexia (1%).

Table 2 Grade 3– 4 hematological toxicities occurring in at least 5% of patients in the randomized CLL clinical study

Based largely on the results of this pivotal study, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bendamustine for the treatment of CLL.

Bendamustine combination therapy for CLL

Bendamustine has also been investigated in combination with other agents (). In one study, bendamustine was evaluated with mitoxantrone in 22 patients.Citation27 In this phase I/II study bendamustine was given in escalating doses of 80 to 240 mg/m2 per cycle divided over 2 to 3 days, while mitoxantrone was administered on day 1 in doses ranging from 8 to 10 mg/m2. Treatment was repeated every 29 days for up to 6 cycles. Majority of patients received bendamustine at either 150 mg/m2 (n = 8) or 240 mg/m2 (n = 6). The ORR was 86% with 27% CR. Median time to progression was 10 months and median over all survival was 39 months. At the recommended dose of 150 mg/m2 7 out of the 8 patients had grade III/IV neutropenia with two developing infections.

Table 3 Combination therapy trials of bendamustine in CLL

In a pilot phase I/II study, bendamustine was combined with mitoxantrone and rituximab (BMR) in 54 patients with B-cell malignancies including 21 with CLL.Citation28 Bendamustine was given at 80 mg/m2 for 2 days, mitoxantrone 10 mg/m2 on day 1 and rituximab week 2 through to 5. Cycle 2 was started on day 36 and subsequent cycles were delivered every 28 days. Treatment was discontinued once a CR or a partial response was achieved: 72% of patients received only 2 cycles of therapy as they achieved a response. Toxicity was mainly hematologic in 43% of the all patients, mostly experiencing grade III/IV leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. CLL patients showed ORR of 95% with 23% CR, remissions were lasting with a median time to progression of 17 months. At this time in the absence of larger studies, this regimen should not be considered outside of clinical trials.

The present dosing of bendamustine with rituximab in relapsed or refractory CLL is based on the following multicenter phase II study (CLL2M) conducted by GCLLSG for relapsed or refractory CLL.Citation17 Patients were treated with bendamustine at 70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2, with rituximab 375 mg/m2 for the first cycle and 500 mg/m2 for the subsequent cycles, treatment was administered every 28 days for a maximum of 6 cycles. In the 81 enrolled patients, the median age was 66 years and they had received a median 2 (range 1–3) prior therapies. After a total of 328 cycles in the 81 evaluable patients, 123 ≥ grade III toxic events were seen, including leukopenia/neutropenia (11.9%), thrombocytopenia (9.1%), and anemia (6.1%). Sixteen episodes of ≥grade III infections were observed, most were managed successfully. However, treatment related mortality occurred in 3 (3.7%) patients, all related to infections during neutropenia. The reported ORR was 77.4%, with 14.5% CRs in 62 evaluable patients. Only 3 (4.8%) patients had progressive disease. No molecular remissions were achieved in the bone marrow, as assessed by 4-color flow cytometry. Difference in responses were noted among the various prognostic groups, with an ORR of 77.7% (9/7) in patients with fludarabine refractory disease, 92.3% (12/13) with 11q deletion, 100% (8/8) with trisomy 12, 44.4% (4/9) with 17p deletion, and 74.4% (29/39) in patients with unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain. These results are encouraging but more mature results of this study and other trials with this combination are needed before this regimen can be recommended as routine therapy.

Conclusions

Bendamustine is clearly an effective, well-tolerated drug for patients with CLL. It has been approved in the US for CLL and rituximab-refractory indolent NHL, and in Germany for CLL, NHL and MM.

Currently, a number of active regimens are available for the front line treatment of CLL. These include fludarabine and rituximab with or without cyclophosphamide, and alemtuzumab. CLL is a disease of the elderly and some of these therapies may not be well tolerated in older patients.Citation11 A major cause of morbidity and mortality are infections. Single agents studies of fludarabine have reported an incidence of grade III/IV infections as high as 27%.Citation29,Citation30 In contrast, in the phase III trial with bendamustine, the rate of grade III/IV infections were only 7%.Citation26 Patients receiving therapy with fludarabine are also at risk of developing autoimmune phenomenon, while bendamustine does not seem to be associated with that risk. Interestingly, in one study Aivado et al noted that with bendamustine, autoimmune phenomenon resolved in 2 out of 2 patients, while no further episodes occurred in 7 patients with a prior history autoimmune disorder.Citation20 Therefore, for patients not suitable for fludarabine-based therapies, either because of infectious risk, autoimmune phenomenon, or other factors, single agent bendamustine seems to provide a more tolerable alternative. Bendamustine also provides a reasonable option for patients not considered appropriate candidates for alemtuzumab either because of recurrent infections or bulky lymphadenopathy. In elderly patients, where clinicians tend to consider chlorambucil as initial therapy, the superiority of bendamustine over chlorambucil with no significant difference in the rate of grade III/IV infections, provides further rationale for its use.Citation26

The greatest potential of bendamustine lies in combination therapy. Early results have shown good efficacy with a tolerable toxicity profile of bendamustine with rituximab in relapsed or refractory CLL.Citation17 GCLLSG is currently testing bendamustine and rituximab in the frontline setting and initiating a comparative study of bendamustine and rituximab with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab in previously untreated patients.

Other active agents of interest in CLL include lenalidomide and flavopiridol. Lenalidomide is currently approved in the US for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome with 5q- and after first line therapy in MM. It has shown good efficacy in CLL with ORRs of 32%–47% in the relapsed or refractory setting.Citation31,Citation32 Flavopiridol also has encouraging activity in CLL, with an ORR of 45% in relapsed or refractory patients.Citation33 More encouragingly, these agents have also shown responses in CLL patients with poor-risk features. Additional clinical trials of these agents with bendamustine may improve outcome of patients with poor-risk CLL. Therefore, to further evaluate this potential, bendamustine is currently being combined with lenalidomide (Cheson pers comm.).

Clinicians need to be familiar with the dosing and toxicities of bendamustine. Based on the results of the phase III trial and two phase I/II studies, at this time the recommended single agent dose of bendamustine for previously untreated CLL is 100 mg/m2 iv on days 1 and 2 every 28 days.Citation26 While for relapsed patients, the GCLLSG recommends a dose of 70 mg/m2 iv for 2 days every 28 days.Citation23 The dose for the combination of bendamustine with rituximab has been suggested at 70 mg/m2 in previously treated and 90 mg/m2 in the frontline setting.Citation17 Major toxicity of bendamustine is myelosuppression, but its degree and duration needs to be better defined. Encouragingly, bendamustine does not appear to be associated with a greater risk of serious infections when compared with agents such as chlorambucil. Nausea and vomiting are common but easily manageable, while an occasional patient may experience an allergic reaction. Presently, it is recommended to use caution when used in patients with mild to moderate renal or hepatic impairment. As bendamustine has not been tested in patients with creatinine clearance <40 mL/min or with AST or ALT > 2.5 times or bilirubin >3 times the upper limits of normal, it should be avoided in this patient population until data demonstrate safety in such patients. As this drug is used more widely, uncommon toxicities may be encountered and should be reported.

Despite extensive use with bendamustine for over 40 years, a number of questions remain unanswered. For example, the optimal dose and schedule have yet to be determined. The dose of bendamustine as a single agent and in combination with other agents such as rituximab has been empiric. For example, the approved dose for rituximab-refractory follicular lymphomas is 120 mg/m2 days 1 and 2 on an every 3 week schedule, while it is 90 mg/m2 in combination with rituximab, given every 4 weeks. However, in CLL the recommended dose is 100 mg/m2 as a single agent in the up-front setting, and 70 mg/m2 in combination with rituximab. Present data seem to suggest efficacy of bendamustine in patients who have failed alkylators and/or fludarabine.Citation20,Citation23,Citation25 What is unknown is the efficacy and tolerability of these drugs after exposure to bendamustine. Further studies are needed to better characterize its role in relapsed patients. In order to change current treatment practices additional clinical trials are needed to determine the efficacy of bendamustine, possibly in combination with more standard front line treatments, similar to the one being initiated by the GCLLSG.

In summary, bendamustine provides an effective and well-tolerated option for the treatment of patients with CLL. Further rational development of this agent will improve the outcome of patients with this common hematologic malignancy.

Disclosures

Dr. Cheson has served on advisory boards for Cephalon and Mundipharma.

References

- RiesLAGMelbertDKrapchoMNational cancer instituteBethesda, MDhttp://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/, based on november 2007 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website, 2008

- ChesonBDBennettJMGreverMNational cancer institute-sponsored working group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatmentBlood199687499049978652811

- HainsworthJDLitchySBartonJHSingle-agent rituximab as first-line and maintenance treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic lymphoma: A phase II trial of the minnie pearl cancer research networkJ Clin Oncol2003211746175112721250

- ByrdJCMurphyTHowardRSRituximab using a thrice weekly dosing schedule in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma demonstrates clinical activity and acceptable toxicityJ Clin Oncol2001192153216411304767

- HuhnDvon SchillingCWilhelmMRituximab therapy of patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemiaBlood2001981326133111520778

- O’BrienSMKantarjianHThomasDARituximab dose-escalation trial in chronic lymphocytic leukemiaJ Clin Oncol2001192165217011304768

- TamCSO’BrienSWierdaWLong-term results of the fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab regimen as initial therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemiaBlood200811297598018411418

- ByrdJCPetersonBLMorrisonVARandomized phase 2 study of fludarabine with concurrent versus sequential treatment with rituximab in symptomatic, untreated patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results from cancer and leukemia group B 9712 (CALGB 9712)Blood200310161412393429

- ByrdJCRaiKPetersonBLAddition of rituximab to fludarabine may prolong progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: An updated retrospective comparative analysis of CALGB 9712 and CALGB 9011Blood2005105495315138165

- HallekMFingerle-RowsonGFinkAImmunochemotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) versus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) improves response rates and progression-free survival of previously untreated patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemiaBlood2008112125,325

- FerrajoliAO’BrienSWierdaWKeatingMTreatment of patients with CLL 70 years old and older: A single center experience of 142 pateintsLeuk Lymphoma200546SupplS95S86

- OzegowskiWKrebsDIMET 3393, (-[1-methyl-5-bis-(β-chloräthyl)-aminobenzimidazolyl-(2)]-butter säurehydrochlorid, ein neues zytostatikum aus der reihi der benzimidazol-losteZbl Pharm197111010131019

- LeoniLMBaileyBReifertJBendamustine (treanda) displays a distinct pattern of cytotoxicity and unique mechanistic features compared with other alkylating agentsClin Cancer Res20081430931718172283

- StrumbergDHarstrickADollKHoffmannBSeeberSBendamustine hydrochloride activity against doxorubicin-resistant human breast carcinoma cell linesAnticancer Drugs199674154218826610

- RummelMJChowKUHoelzerDMitrouPSWeidmannEIn vitro studies with bendamustine: Enhanced activity in combination with rituximabSemin Oncol200229121412170426

- ChowKUSommerladWDBoehrerSAnti-CD20 antibody (IDEC-C2B8, rituximab) enhances efficacy of cytotoxic drugs on neoplastic lymphocytes in vitro: Role of cytokines, complement, and caspasesHaematologica200287334311801463

- FischerKStilgenbauerSSchweighoferCDBendamustine in combination with rituximab for patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A multicentre phase II trial of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG)Blood2008112128,330

- RummelMJAl-BatranSEKimSZBendamustine plus rituximab is effective and has a favorable toxicity profile in the treatment of mantle cell and low-grade non-hodgkin’s lymphomaJ Clin Oncol2005233383338915908650

- RobinsonKSWilliamsMEvan der JagtRHPhase II multicenter study of bendamustine plus rituximab in patients with relapsed indolent B-cell and mantle cell non-hodgkin’s lymphomaJ Clin Oncol2008264473447918626004

- AivadoMSchulteKHenzeLBurgerJFinkeJHaasRBendamustine in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results and future perspectivesSemin Oncol200229192212170428

- BremerKHigh rates of long-lasting remissions after 5-day bendamustine chemotherapy cycles in pre-treated low-grade non-hodgkin’s-lymphomasJ Cancer Res Clin Oncol200212860360912458340

- KathRBlumenstengelKFrickeHJHoffkenKBendamustine monotherapy in advanced and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemiaJ Cancer Res Clin Oncol2001127485411206271

- BergmannMAGoebelerMEHeroldMEfficacy of bendamustine in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results of a phase I/II study of the German CLL Study GroupHaematologica2005901357136416219572

- LissitchkovTArnaudovGPeytchevDMerkleKPhase-I/II study to evaluate dose limiting toxicity, maximum tolerated dose, and tolerability of bendamustine HCl in pre-treated patients with B-chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (binet stages B and C) requiring therapyJ Cancer Res Clin Oncol20061329910416292542

- NiederleNBalleisenLHeitWBendamustine versus fludarabine as second-line treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia – first interim results of a randomized studyAnnals of Onclogy200819379

- KnaufWULissitchkovTAldaoudABendamustine versus chlorambucil as first-line treatment in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an updated analysis from an international phase III studyBlood2008112728,2091

- KopplerHHeymannsJPandorfAWeideRBendamustine plus mitoxantrone – a new effective treatment for advanced chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: Results of a phase I/II studyLeuk Lymphoma20044591191315291348

- WeideRPandorfAHeymannsJKopplerHBendamustine/Mitoxantrone/Rituximab (BMR): A very effective, well tolerated outpatient chemoimmunotherapy for relapsed and refractory CD20-positive indolent malignancies. final results of a pilot studyLeuk Lymphoma2004452445244915621757

- RaiKRPetersonBLAppelbaumFRFludarabine compared with chlorambucil as primary therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemiaN Engl J Med20003431750175711114313

- CatovskyDRichardsSMatutesEAssessment of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (the LRF CLL4 trial): A randomised controlled trialLancet200737023023917658394

- FerrajoliALeeBNSchletteEJLenalidomide induces complete and partial remissions in patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemiaBlood20081115291529718334676

- Chanan-KhanAMillerKCMusialLClinical efficacy of lenalidomide in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results of a phase II studyJ Clin Oncol2006245343534917088571

- HeeremaNAByrdJCAndritsosLAClinical activity of flavopiridol in relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities: Updated data on 89 patientsBlood2007110914,3107