Abstract

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma carries a dismal prognosis and remains a significant cause of cancer morbidity and mortality. Most patients survive less than 1 year; chemotherapeutic options prolong life minimally. The best chance for long-term survival is complete resection, which offers a 3-year survival of only 15%. Most patients who do undergo resection will go on to die of their disease. Research in chemotherapy for metastatic disease has made only modest progress and the standard of care remains the purine analog gemcitabine. For resectable pancreatic cancer, presumed micrometastases provide the rationale for adjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation (CRT) to supplement surgical management. Numerous randomized control trials, none definitive, of adjuvant chemotherapy and CRT have been conducted and are summarized in this review, along with recent developments in how unresectable disease can be subcategorized according to the potential for eventual curative resection. This review will also emphasize palliative care and discuss some avenues of research that show early promise.

Introduction

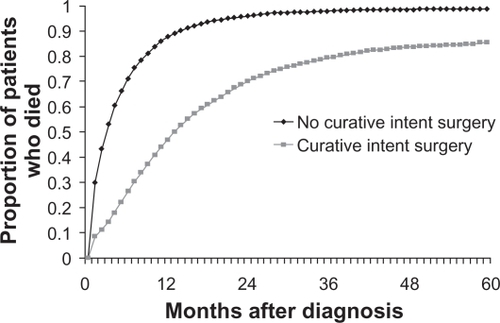

Despite all efforts at developing effective therapy, pancreatic adenocarcinoma carries a dismal prognosisCitation1 and remains a significant cause of cancer morbidity and mortality. There is no screening test for this disease, and patients are generally only identified when already symptomatic with weight loss, back or abdominal pain, or obstructive jaundice. Most patients survive less than 1 year; chemotherapeutic options prolong life minimally. The best chance for long-term survival is complete resection, which offers a 3-year survival of only 15%.Citation2 Most patients who do undergo resection will go on to die of their diseaseCitation3 (see ). Research in chemotherapy for metastatic disease has made only modest progress and the standard of diabetes mellitus care remains the purine analog gemcitabine.Citation4

Figure 1 Survival of patients with pancreatic cancer categorized by the receipt of curative intent surgery. Copyright © 2007. Reproduced with permission from Shaib Y, Davila J, Naumann C, EI-Serag H. The impact of curative intent surgery on the survival of pancreatic cancer patients: a U.S. Population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(7):1377–1382.

Well-established risk factors for pancreatic cancer include smoking and family history. There is a slight increased risk with some familial cancer syndromes, including Lynch syndromeCitation5 and BRCA2 mutations.Citation6 Recently, obesity has been identified as a modifiable risk factor in the development of and mortality from pancreatic cancer.Citation7–Citation10 There are no screening recommendations for this disease.

In this article, we will review current treatments for pancreatic cancer. We will discuss adjuvant therapy and recent developments in how unresectable disease can be subcategorized according to the potential for eventual curative resection. Considering the bleak prognosis of this disease, an important challenge is maintaining quality of remaining life with multidisciplinary support. Therefore, we will emphasize palliative care. Finally, we will discuss some avenues of research that show early promise as our understanding of the biology of this devastating disease improves.

Managing resectable disease

Surgical resection for treatment of localized pancreatic cancer is currently the best chance for cure. Unfortunately, up to 85%Citation11 of patients initially present in advanced or metastatic stages, and curative resection is only possible in roughly 13% of patients.Citation1 Even in patients who present with more favorable disease and undergo surgery with curative intent, there is a high rate of relapse,Citation12,Citation13 with high local recurrence rates of up to 50% following surgery aloneCitation14 leading to a 5-year survival rate of under 5%.Citation1 This aggressive recurrence pattern is highly suggestive of the presence of micrometastases at the time of surgery.Citation11 For resectable pancreatic cancer, presumed micrometastases provide the rationale for adjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation (CRT) to supplement surgical management. Numerous randomized control trials, none definitive, of adjuvant chemotherapy and CRT have been conducted, summarized in .

Table 1 Randomized control trials of adjuvant chemotherapy and CRT

Adjuvant CRT and chemotherapy: regional differences

The earliest prospective randomized trial to suggest a survival benefit from the addition of postoperative CRT was the Gastro-Intestinal Study Group (GITSG) trial.Citation15 Patients receiving bolus fluorouracil (5-FU) and a split course of 20 Gy radiation for 2 cycles after primary surgery followed by maintenance 5-FU were reported to have a median overall survival (OS) of 20 months compared with 11 months with surgery alone. Though this study had a small sample size, early termination, and suboptimal radiation dosing, it was still highly influential, making concurrent adjuvant CRT the standard of care in the United States. In Europe, however, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) conducted a similar study comparing postoperative radiation with continuous infusion of 5-FU without subsequent chemotherapy maintenance. The median duration of survival was 19.0 months for the observation group and 24.5 months in the treatment group but the study did not reach statistical significance (two-tailed test, P = 0.208).Citation16 Thus, CRT did not become standard practice in Europe. However, the European study may have an inappropriate statistical design that biased against the detection of treatment effects. As a follow up to the positive GITSG study, a one-tailed rather than two-tailed test would have been appropriate and would have brought the results to significance (P = 0.049) in favor of CRT.Citation17 This finding is even more robust considering that nearly 20% of the patients assigned to the CRT arm were not even treated, which would further bias the study against CRT.

Despite these criticisms, the debate continued. A second line of evidence has led most European clinicians to adopt chemotherapy rather than CRT as the current standard of care. The Europen Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer-1 (ESPAC-1) study showed a near-doubling of benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy with infusional 5-FU and leucovorin (LV), but no benefit with 5-FU and radiation. This trial had a 2 × 2 factorial design comparing CRT to observation and infusional 5-FU/LV to observation. The estimated 5-year survival rate was 10% among patients assigned to receive CRT and 20% among patients who did not receive CRT (P = 0.05).Citation18 However, this study may have suffered from selection bias and an insufficient sample size for a 2 × 2 study design.Citation19 In addition, there was an excessive rate of local recurrence in the CRT arm, suggesting the radiation schedule was suboptimal.Citation20

Outside the United States, adjuvant chemotherapy remains the focus of trials

Trials of adjuvant chemotherapy alone have continued subsequent to the EORTC and ESPAC-1 trials. A trial of 5-FU and cisplatin based in Japan showed no difference, and possibly harm in patients receiving this aggressive adjuvant chemotherapy regimen.Citation21 The CONKO-001 trial of 368 patients showed a benefit in disease-free survival (DFS) for patients receiving gemcitabine compared with observation (median DFS, 13.4 months vs 6.9 months), but only a small and insignificant difference in OS.Citation22 A similar but smaller study in Japan did not reach statistical significance.Citation23 At the 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting, Neoptolemos et alCitation24 presented the results of ESPAC-3 trial in which patients were randomized 1:1 to adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-FU/LV bolus vs gemcitabine. The OS was 23.0 months vs 23.6 months (P = 0.39) in this large study, with the conclusion that gemcitabine is not superior to 5-FU in the adjuvant setting.Citation24 However, ESPAC-4, currently enrolling in Europe, is based on the assumption that gemcitabine is superior to 5-FU in the adjuvant therapy setting. ESPAC-4 will directly compare gemcitabine to a gemcitabine–capecitabine combination after resection of pancreatic cancer, again without radiation. Enrollment of more than 1,000 patients is planned. Unfortunately, there will be no comparison of adjuvant CRT to chemotherapy alone, maintaining the regional differences in both practice and clinical trials.

Can locally advanced disease be resected?

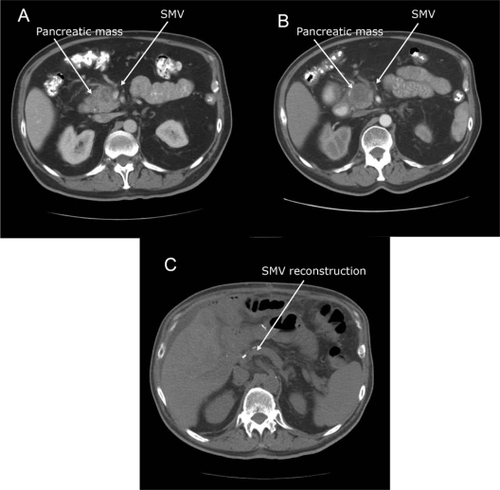

The most significant advance in treating locally advanced disease has been the recognition that treatment has potential to downstage tumors to allow secondary surgical managementCitation25 (see ). With this new paradigm of possibly downstaging tumors, locally advanced pancreatic cancer is categorized into 2 distinct groups: borderline resectable and unresectable, summarized in .Citation25,Citation26 Before these criteria were established, the standard of care for locally advanced disease had been concurrent CRT without expectation of making the disease resectable.Citation27,Citation28 These criteria allow borderline resectable disease with no vascular involvement to be distinguished from locally advanced unresectable disease with vascular involvement. Both these categories may benefit from neoadjuvant therapy, and secondary resection has emerged as an important therapeutic goal.

Figure 2 Downstaging with neoadjuvant therapy: 59-year-old man with a 2.2 × 1.8 cm pancreatic head mass found to be pancreatic adenocarcinoma on biopsy A) Pretreatment scan. Note severe SMV impingement, which fits criteria for borderline resectable disease B) Post-treatment scan. The patient was reated with neoadjuvant capecitabine 1500 mg po bid and concurrent radiation. The SMV is less confined; the pancreas mass remains similar in size. C) Post-operative scan. The patient underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy with jugular SMV reconstruction.

Table 2 Criteria for defining resectability statusCitation25,Citation26

Early attempts at preoperative treatment using chemotherapy,Citation29 radiotherapy,Citation30 and CRTCitation31 demonstrated that neoadjuvant treatment of previously inoperable pancreatic tumors may result in potentially curative secondary surgery. In this scenario, the chief objective of neoadjuvant therapy for borderline resectable patients is to induce a partial tumor response and, therefore, increase the likelihood of complete resection with negative margins. Additionally, exposure of the tumor to chemotherapeutic agents before resection allows for the sensitivity of the tumor to those agents to be assessed. Tumors that progress despite therapy may be those with aggressive biology that would progress even if resected and treated adjuvantly. Those patients who progress during neoadjuvant treatment are, therefore, spared the morbidity and mortality of major surgery. On the other hand, patients with favorable responses to preoperative therapy as demonstrated by radiographic tumor regression and improvement in serum tumor marker levels may have the best chance for an R0 resection and a favorable long-term outcome.Citation25

Might neoadjuvant CRT improve resectability and survival?

Preoperative therapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer has been the focus of multiple phase II trials. Several of these trials have demonstrated encouraging rates of secondary resection.Citation32,Citation33 The emergence of borderline resectable disease as a separate category in trials in 2002 (see ) has opened the possibility of evaluating the role of neoadjuvant CRT. Previously, trials failed to distinguish borderline resectable from resectable or borderline unresectable disease. In the single study to address this subgroup, Brown et alCitation34 tested a combination of radiosensitizing agents with 50.4 Gy of radiation in 13 patients with borderline resectable disease. All patients underwent secondary surgery with intent for cure. Eighty-five percent (11 patients) had complete, or R0, resections, which led to a 2-year survival of 69% (n = 9) and 8 patients disease-free at 2 years.

Table 3 Summary of studies for locally advanced pancreatic cancer

In a phase II trial by Massucco et alCitation33 of neoadjuvant gemcitabine with 45 Gy radiation in borderline resectable and unresectable locally advanced disease, 8 patients who had unresectable disease responded favorably to neoadjuvant therapy and went on to resection. These patients had similar OS and DFS to those with initially resectable disease receiving the same regimen.Citation33 Like many previous trials, this study found margin status to be the most powerful predictor of survival. This trial is interesting for having used gemcitabine as a radiation sensitizer, albeit at only 50 mg/m2 twice weekly,Citation33 far less than the full dose of gemcitabine, 1,000 mg/m2 weekly, that has been shown to be of benefit in metastatic disease,Citation4 and which would be hypothesized to better treat micrometastases.

Role of gemcitabine in CRT

Historically, 5-FU has been used as a radiation sensitizer in pancreatic cancer, even though it has been demonstrated to be inferior to gemcitabine for treating metastatic disease.Citation4 The Massucco et alCitation33 trial, described above demonstrated the possibility of secondary surgical resection after CRT, is one of a series of trials exploring the potential of gemcitabine as a radiation sensitizer. In the Munich Pancreas Trial, gemcitabine at a dose of 300 mg/m2 was give on days 1, 15, and 29 with 5-FU continuous infusion and concurrent radiation (45–50 Gy) in 32 patients with locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. They demonstrated an overall response rate (RR) of 62.5%. An impressive 37.5% of patients were found to be resectable after neoadjuvant treatment.Citation35

An number of phase I and II trials have explored full-dose gemcitabine given in conjunction with varying doses of radiotherapyCitation36,Citation37 and have shown encouraging RRs, allowing in some cases for secondary surgery for previously unresectable disease. In a single-arm trial of 41 patients, Small et alCitation38 have reported that full-dose gemcitabine with concurrent radiation (36 Gy) in nonmetastatic pancreatic cancer resulted in 3 of 9 cases of borderline resectable disease going on to secondary resection; 1 of 14 unresectable patients went on to resection. The 12-month survival rate in this study was 94% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 82%–100%) for primarily resectable disease, 76% (95% CI: 47%–100%) in secondary resection after neoadjuvant treatment, and 47% (95% CI: 19%–75%) for unresectable patients. Of 17 surgically resected patients, 16 showed negative margins at the time of resection,Citation36 suggesting that the CRT may have contributed to local control; however, the large overlap in CIs for these results raises the necessity of a larger scale study to confirm the benefit of full-dose gemcitabine with concurrent radiation.

Because of the theoretical importance of full-dose gemcitabine for treating micrometastatic disease and for improving RRs, some researchers argue for the use of gemcitabine before and after 5-FU-based CRT in a sandwich regimen, explored in the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 97-04 trial. 5-FU was used as a radiosensitizer in both groups. Before and after CRT, patients received gemcitabine or 5-FU in a 1:1 ratio. OS was similar in both groups (18.8 months vs 16.9 months), but in subgroup analysis, patients with resectable pancreatic head mass had significant benefit on the gemcitabine arm (20.5 months vs 16.9 months, P = 0.033),Citation39 again suggesting the importance of gemcitabine in this disease.

Comparing CRT to chemotherapy: neoadjuvant intent

Although there have been no recent trials comparing adjuvant chemotherapy to CRT for resected pancreatic cancer, this comparison is being made in the setting of locally advanced pancreatic cancer.

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group-4201(ECOG-4201) is the first study that directly compared gemcitabine in combination with radiation therapy vs gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. In the radiation arm, gemcitabine was given at a dose of 600 mg/m2 weekly concurrent with radiation, and then followed by 5 cycles of full-dose gemcitabine. The concurrent CRT was found to be more myelosuppressive and was also associated with considerable gastrointestinal toxicity and fatigue. However, the addition of radiation therapy to gemcitabine significantly improved OS (P = 0.034) and tripled the survival rate at 24 months for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer.Citation40

Does more chemotherapy improve RRs to radiation?

In a small trial, Marti et alCitation41 found that adding cisplatin to gemcitabine with 45 Gy concurrent radiation was well tolerated and allowed some patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer to go on to resection. However, this benefit has not been borne out in phase III trials. The French 2000–2001 Fédération Francophone de la Cancéologie Digestive/Société Française de Radiothérapie Oncologie (FFCD/SFRO) study was a phase III trial comparing intensive induction CRT (60 Gy, infusional 5-FU and intermittent cisplatin) followed by maintenance gemcitabine with gemcitabine alone for locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. This trial was a departure from the European approach of neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone. The intensive regimen unfortunately showed a significant decrease in OS from 13 to 8.6 months,Citation42 possibly associated with toxicity of the aggressive chemotherapy. Although RR was not reported, there was similar tumor progression in both arms. The role of platinum agents in CRT for pancreatic cancer remains unsupported by evidence.

Who is resectable? radiologic staging

Although computed tomographic (CT) scans are the standard imaging modality at present, they are often unable to differentiate active pancreatic cancer from necrotic or fibrous tissue.Citation43 Therefore, they are ineffective at identifying which tumors have been adequately downstaged to allow resection. Indeed, there are reports of complete pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy not appreciated on preoperative scans.Citation44 Thus, an important area of research is the development of advanced postprocessing techniques to increase the resolution of CT scanning for better restaging of disease,Citation45 an important unmet need at present. An alternate modality for clinical assessment is 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose-positron emission tomographic scanning, which in 1 small study has been used to quantify response to neoadjuvant treatment.Citation46 One approach to this dilemma is to err on the side of secondary surgery for curative intent, but this may increase the rate of futile surgery and subsequent complications.

The future of neoadjuvant therapy in borderline unresectable and resectable diseases

As the above definitions of resectability are incorporated into clinical trials and surgical technique and as criteria for assessment of margin status become standardized, the relative contributions of chemotherapy and radiation to the benefit neoadjuvant therapy will become more clear.Citation14 Taken together, the trials conducted in locally advanced pancreatic cancer suggest that CRT is not only tolerable but also can downstage the disease, thus enabling secondary resection, possibly prolonging survival. The possibility of using full-dose gemcitabine as a radiation sensitizer is intriguing, but phase III trials have not yet been conducted with full-dose gemcitabine as a radiation sensitizer. Until such trials are available, a reasonable standard of care for locally advanced pancreatic cancer is the RTOG 97-04 sandwich approach with full-dose gemcitabine before and after CRT with 5-FU.Citation39

Metastatic disease: treating the patient not the disease

Once pancreatic cancer becomes metastatic, it is uniformly fatal. At this point, the goal of treatment shifts away from curative attempts and toward prolonging survival while maintaining good quality of life. Chemotherapy is an important component of palliative care but must be deployed as part of a multidisciplinary approach to treat pain, minimizing weight loss, and manage declines in functional status.

Pain control

Pain control in advanced pancreas cancer needs to be aggressive and comprehensive. The appropriate initial line of attack is long-acting narcotics supplemented by short-acting preparations for breakthrough pain. A key principle is to balance pain control against oversedation in order to maintain both comfortable and functional living. For patients who suffer from postprandial pain, multidisciplinary support is necessary. Postprandial pain may be alleviated by pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), or celiac plexus block, both detailed below. Nutritional support is also important in staving off cachexia, which can interfere with pain management options like transdermal fentanyl.

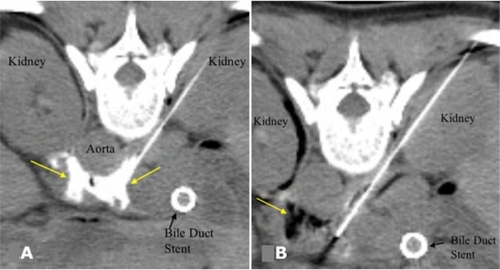

For patients who have localized cancer-related pain, often described as band-like and radiating from the epigastrium, an important palliative option is neurolytic celiac plexus block (NCPB). In this procedure, an analgesic, such as lidocaine and an anti-inflammatory or a neurolytic agent, can be introduced to the celiac plexus. At some centers, this procedure may be done endoscopically with endoscopic ultrasound guidance, but it can also accomplished by fluoroscopic and CT guidance (see ). The approach may be made from either an anterior or an posterior approach based on anatomy and the patient’s comfort.Citation47 Celiac plexus block may also be applied intraoperatively on initial surgical exploration with 50% ethanol or 6% phenol under direct visualization during laparotomy.Citation48 In a meta-analysis, partial or complete pain relief was achieved in 90% of patients via NCPB.Citation49 NCPB can decrease the subsequent onset pain even in patients without preexisting pain at the time of surgery.Citation50 Although the efficacy of this procedure is high, the duration or response is limited. As patients live longer, the efficacy of repeated NCPB diminishes, presumably due to disease metastasizing past the splanchnic bed,Citation47 and systemic analgesics become necessary to control pain.

Figure 3 A) CT image after injection of a small volume of dilute contrast agent through both needles, confirming correct distribution of injected contrast around the celiac axis (arrows) prior to alcohol injection. B) After injection of alcohol, darkened region (arrow) shows its distribution in the vicinity of the celiac plexus. Copyright © 2007. Reproduced with permission from Arellano RS. Image-guided pain management, Part 1: celiac plexus block for palliative pain relief. Radiology Rounds, Vol 5. Boston, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital; 2007.

PERT

Patients with pancreatic cancer may suffer from symptoms of pancreatic enzyme deficiency and malabsorption. The deficiency stems from both disease-related obstruction of the pancreatic duct and destruction of normal pancreatic parenchyma, as well as unwanted consequences from interventional or surgical procedures.Citation51 The rate of malabsorption can be 85%–90% in patients with pancreatic carcinoma, even in those who have not had surgery.Citation52 Malabsorption can lead to vitamin and mineral deficiencies, particularly the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. Symptoms of pancreatic enzyme deficiency include abdominal pain and distention, particularly postprandial, flatus, belching, diarrhea, steatorrhea, and weight loss.

To avoid symptoms and sequela of these deficiencies, it is important to provide pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT). A standard initial dose of replacement therapy is 50,000 IU of lipase with each meal. The dosage is then titrated to symptoms, leading eventually to a widely varying therapeutic range. PERT can be optimized with the addition of a proton-pump inhibitor, which increases intestinal pH and leads to decreased inactivation of prescribed PERT.Citation53

Nutritional status

Pancreatic cancer is associated with cachexia, which is in and of itself a significant systemic symptom. Weight loss of 5% or more has been associated with an increased rate of metastatic disease, which renders surgical resection moot.Citation54 It is not clear whether weight loss is causative since those with more tumor burden may lose more weight. Weight loss is, therefore, useful as a prognostic indicatorCitation55 and has even been considered an end point in major trials.Citation4

Cachexia has important implications for symptom management. Because many cachectic patients with pancreatic cancer swallow poorly or have significant nausea and vomiting, transdermal fentanyl is an attractive treatment option. Unfortunately, cachexia has been demonstrated to decrease absorption of the narcotic due to lack of subcutaneous fat.Citation56

For patients who have intractable nausea and vomiting on the basis of mechanical obstruction not amenable to endoscopic stenting, a gastric bypass surgery may be necessary to allow patients to continue to eat. A gastrojejunostomy with anastomosis between the jejunum and the anterior or posterior wall of the stomach can be performed to alleviate gastric outlet obstruction.Citation57

Hyperbilirubinemia

Clearance of gemcitabine depends on a functioning liver. Thus, biliary tract obstruction due to tumor or complications of surgery, which may lead to hyperbilirubinemia as evidenced by jaundice, pruritus, and even direct neurotoxicity,Citation58 can significantly delay optimal treatment. If the cancer is unresectable, biliary obstruction can often be relieved endoscopically by the placement of biliary stents.Citation59 Stenting can decompress the biliary passages and relieve symptoms in the setting of pancreatic cancer, with 60% of patients experiencing complete resolution of pain and 25% of patients experiencing partial pain relief.Citation59 However, stenting can also lead to many infectious complications.Citation60 The main complication is stent occlusion, which accounts for the risk of cholangitis of approximately 7% in the setting of malignant biliary obstruction.Citation61 Biliary stenting is also associated with up to a 10% postprocedure incidence of cholecystitis.Citation62

To reduce the risk of stent occlusion and subsequent infectious complications, plastic stents, if used for malignant biliary obstruction, must be changed regularly. A more occlusion-resistant alternative to plastic stents is metal stents, which are, therefore, the intervention of choice in patients with malignant distal obstructive jaundice due to pancreatic carcinoma.Citation63 Plastic stents should only be used in the palliative setting in patients with short predicted survival, who are not expected to require the patency benefits of metal stents. Historically, the surgical literature has reported postoperative infectious complications associated with preoperative stenting for patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.Citation64–Citation66 However, a Cochrane database review found no significant increased risk of infectious complications in this group,Citation67 so there is no known rationale for avoiding this important palliative procedure.

In some cases, palliative surgery to bypass the biliary obstruction may be possible if endoscopic stenting is not feasible. Patency rates appear to be superior with surgical as opposed to endoscopic interventions, but at the cost of surgical morbidity.Citation63 In addition, patients found to have unresectable disease at the time of laparotomy may benefit from a surgical biliary bypass with an hepaticojejunostomy, a procedure to anastomose the hepatic duct to the jejunum to relieve obstruction.Citation57

Chemotherapy for metastatic disease

The primary intent of chemotherapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer is to relieve symptoms while prolonging survival. By causing tumor regression, chemotherapy may relieve the symptoms of biliary obstruction, reduce ascites, and contribute to resolving pain. Mallinson et alCitation68 published the first randomized, controlled trial to demonstrate a survival benefit with systemic chemotherapy in 1980. Patients with unresectable disease (diagnosed at laparotomy) were treated with 5-FU, methotrexate, vincristine, and cyclophosphamide. Chemotherapy treatment was associated with a significant improvement in OS of 44 weeks compared with only 9 weeks with best supportive care (BSC).Citation68 Several other combination regimens were then studied with promising results in phase II trials, but upon phase III evaluation, resulted in only modest improvements in progression-free survival (PFS) with no advantage in OS.Citation69,Citation70 This pattern of improvement in PFS without an OS benefit is common in subsequent trials in pancreatic cancer as well.

The next advancement in the treatment of metastatic disease was the establishment of single-agent gemcitabine as standard of care in the late 1990s. Burris et alCitation4 conducted the pivotal trial. They compared weekly gemcitabine bolus of 1,000 mg/m2 to weekly 5-FU bolus. Due to the palliative nature of chemotherapy at this stage, a clinical benefit response (CBR) scale, a composite score for pain, was used as the primary end point. A significant 23.8% of patients receiving gemcitabine had a CBR vs only 4.8% of patients in the 5-FU arm with a significant benefit in OS of 5.65 months vs 4.41 months, with few adverse events associated with the gemcitabine chemotherapy.Citation4

Previous efforts to improve on chemotherapy were made using 5-FU as the basis for chemotherapy regimens, with little success; even a meta-analysis of 5-FU combination regimens showed no benefit of 5-FU-based combination therapy compared with 5-FU alone.Citation71 For the past several years, researchers have been duplicating this experience by adding different chemotherapies to a gemcitabine backbone, again with limited success.

Efforts to improve upon gemcitabine: phase II promise does not predict success in phase III

Although single-agent gemcitabine demonstrated its superiority over 5-FU in metastatic pancreatic cancer, the benefits were still modest.Citation4 A number of trials have tried to improve the efficacy of gemcitabine by adding a number of other agents (see ). Other efforts have been made to improve the efficacy of gemcitabine itself. In phase I studies, gemcitabine at a concentration of 20 μmol/L was found to maximize the rate of active gemcitabine triphosphate formation. This correlates to a fixed dose rate (FDR) of 10 mg/m2/min.Citation72 A phase II trial of FDR gemcitabine was also promising. OS on the FDR gemcitabine arm was associated with a significant improvement in OS of 8 months vs 5 months with standard dosing.Citation73 Despite this encouraging data from a phase II trial, there was no benefit observed when FDR gemcitabine was evaluated as one of the arms of ECOG-6201, a large phase III trial that also looked at the combination of gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin.Citation74 Although FDR gemcitabine was associated with the longest OS (6.2 months), this outcome did not meet criteria for superiority, nor did the doublet of gemcitabine with the platinum, another area where multiple efforts have been made.

Table 4 Phase III studies comparing addition to gemcitabine therapy

Efforts adding a platinum

There has been promising phase II data for adding a platinum to gemcitabine. For example, the French Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Group in Oncology (GERCOR) showed promising results with oxaliplatin combined with gemcitabine.Citation75 When conducted in a phase III trial, however, despite improvements in RRs and PFS, OS was not statistically different.Citation74,Citation76 ECOG-6201, a larger trial, was designed to test 2 promising approaches against standard single-agent gemcitabine in 832 patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Disappointingly, the addition of oxaliplatin increased neither OS nor PFS significantly when compared with standard gemcitabine.Citation74 Many authors consider this the definitive trial of platinum combinations, although interest in the combination continues.

Data presented at 2009 ASCO, including the Gruppo Italiano Pancreas-1(GIP-1) trial of gemcitabine combined with cisplatin vs gemcitabine alone in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer, failed to demonstrate any OS benefit or benefit in RR to adding the platinum.Citation77

Many explanations for this consistent shortcoming among phase III trials of gemcitabine with a platinum drug have been proposed. Some postulate that this may be due to second-line therapy crossovers, or that combination therapy candidates need to be carefully selected for good performance status.Citation76,Citation78

Do meta-analyses shed light on the role of a platinum analog?

In the metastatic setting, till date, the only first-line phase III combination chemotherapy trial to show benefit over single-agent gemcitabine was the addition of erlotinib.Citation79 Despite promising results with the addition of a platinum agent in the phase II setting, when conducted in a phase III trial, despite improvements in RRs and PFS, OS is not statistically different.Citation74,Citation76 A number of meta-analyses have been undertaken in an effort to tease out the benefit of combination therapy.Citation80 Heinemann et alCitation81 pooled the results of the GERCOR/Italian Group for the Study of Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer (GISCAD) intergroup study comparing gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin to gemcitabine and a German multicenter trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin vs gemcitabine and concluded that a platinum analog significantly improved PFS and OS as compared with single-agent gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer in patients with a good performance status,Citation81 similar to other pooled analyses.Citation80 These meta-analyses raise interesting questions, but are not comprehensive enough to dictate standard of care. For example, 2 phase III trials not included in the Heinemann analysis did not show an advantage when cisplatin was combined with gemcitabine.Citation82,Citation83 Also discouragingly, a different meta-analyses showed no significant improvement in survival when using cisplatin in combination with gemcitabine.Citation84

Efforts adding capecitabine

Another notable example of the difference in results between phase II and III trials in pancreatic cancer are trials of capecitabine, which shows activity comparable with gemcitabine in phase II trials.Citation85 In the phase III setting, however (see ), there was no statistically significant difference between the gemcitabine plus capecitabine arm compared with the gemcitabine arm.Citation86 Interestingly, in a post hoc analysis, patients in this study with a Karnofsky Performance score (PS) of >90 had a significantly improved OS of 10.1 months vs 7.4 months, suggesting again that the subset of patients with excellent PS may benefit from combination therapy.Citation80 The positive phase II results may stem in part from better PS in phase II trial participants than in larger trials.

Targeting the EGFR pathway: statistical significance does not mean clinical relevance

Of all molecularly targeted agents studied in phase III trials, only erlotinib, targeting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (HER-1/EGFR), has demonstrated statistical significant improvement over gemcitabine alone. However, the clinical benefit of this addition is uninspiring. In a phase III randomized trial, erlotinib with gemcitabine was associated with statistically significant 1-year survival advantage of 23% vs 17%; PFS of 3.75 months vs 3.55 months; and OS of 6.24 months vs 5.91 months. This was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) due to all of these end points achieving statistical significance, a feat that could not be demonstrated in cytotoxic agents above. Clinically, however, the addition of erlotinib manifests a median benefit of only 0.33 months, or about 10 days.Citation79

The most common toxicity of anti-EGFR agents is an acne-like rash, which may vary in severity. Interestingly, in a review of both cetuximab and erlotinib in a variety of solid tumors, multiple studies demonstrate a correlation between efficacy and severity of the acneiform rash. In a phase II study of cetuximab and gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer, not only the presence of the rash but also the severity of it was associated with longer survival.Citation87

Second-line therapy: an area of great need

Currently, there is a lack of proven therapy in the second-line, a great unmet need as most patients do not have a good response to first-line therapy. The only established second-line regimen after failure of first-line gemcitabine in the metastatic setting is 5-FU with oxaliplatin. In the CONKO-003 trial, a phase III trial of oxaliplatin and 5-FU with folinic acid vs BSC, patients who received second-line therapy were noted to have an OS of 40 weeks compared with 34.4 weeks after initiation of second-line chemotherapy (P = 0.0312).Citation88 It is notable that in this study, after 46 of 165 patients were randomized, the BSC arm was closed due to participating centers deciding that BSC alone was no longer acceptable. This benefit, although statistically significant, is small and points to the dire need for more investigation.

Directions of current research

A number of genetic alterations have been shown to occur in pancreatic cancer. Commonly mutated genes include the oncogenes K-ras (75%–100%), HER2/neu (about 65%), p16Ink4a (>90%), notch1, Akt-2, and COX-2 and also the tumor suppressor genes p53 (45%–75%), DPC4 (approximately 50%), FHIT (70%), and BRCA2. Despite this diversity of mutations, none of these genes is currently being targeted in clinical practice.Citation89 The promise of targeted therapies nevertheless continue to hold great interest in this disease, and other approaches, such as concentrating the role of the tumor stroma, overcoming resistance mechanisms to chemotherapy, and recruiting immune defenses, show early promise and are highlighted below.

Targeted therapies: efforts to improve on the best available

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib is the first and only molecularly targeted therapy approved by the FDA for first-line treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer in combination with gemcitabine.Citation79 As this is currently FDA approved, it is discussed above. Several investigators have sought to build upon the benefit of erlotinib. A phase I trial was conducted of erlotinib CRT with gemcitabine followed by maintenance erlotinib for locally advanced pancreatic cancer.Citation90 A retrospective study of single-agent erlotinib as second-line therapy showed no observed responses.Citation91 Second-line erlotinib with capecitabine in gemcitabine refractory pancreatic cancer showed a modest median survival time of 6.5 months and a RR of 10%.Citation92

Cetuximab: limited activity

A monoclonal antibody against HER1/EGFR, cetuximab, has been demonstrated to have activity in pancreatic cancer when combined with gemcitabine.Citation87 This combination is being tested in the phase III setting, but unfortunately, preliminary reports suggest that this trial will likely fail to significantly improve OS timeCitation93 (see ). Nongemcitabine-based first-line therapy with cetuximab has also been studied. An ECOG phase II trial with randomization between irinotecan and docetaxel vs irinotecan and docetaxel plus cetuximab demonstrated modest improvements in clinical response with an OS time of 7.4 months with cetuximab vs 6.5 months without.Citation94

Table 5 Phase III trials of molecularly targeted agents for advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer

Targeting the vascular epithelial growth factor may be inactive in pancreatic cancer

The vascular epithelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors are attractive targets for antineoplastic therapy, particularly as they have a theoretical benefit in improving chemotherapy delivery to tumor. In a phase II trial, the anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab demonstrated activity in advanced pancreatic cancer with a RR of 21% and a median survival time of 8.8 months.Citation95 Yet again, these phase II results were not borne out in the phase III setting. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 8030, a phase III, trial showed disappointing results for OS and was terminated early.Citation96 Sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor against VEGFR, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, Kit, and Flt-3, was demonstrated to have no activity in combination with gemcitabine in phase II trial,Citation97 although it is being investigated in the second-line setting.Citation98

Secreted protein acid rich in cysteine (SPARC): the stroma as the target

The role of the pancreatic cancer stroma is an area of active research regarding the pathogenesis of the disease and its vigorous resistance to chemotherapy.Citation99,Citation100 Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is characterized by a strong desmoplastic reaction, which may promote the malignant phenotype.Citation101,Citation102 Pancreatic stellate cells (PSC) have been shown to produce substances that aid in the invasion of pancreatic cancer. The level of paracrine secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) from PSC has been demonstrated to be inversely proportional to survival.Citation101 This makes SPARC in the PSCs an attractive adjunct target. Nab-paclitaxel uses endogenous albumin pathways via binding of the albumin to SPARC. In a phase II trial as first-line therapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer, nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine were given on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle. One patient had a complete response to therapy, 12 patients (24%) had partial response (PR), and 20 patients (41%) had stable disease (SD). Median PFS increased from 4.8 months for SPARC-negative patients to 6.2 months for SPARC-positive patients.Citation103 In a proof-of-principle parallel study in mouse xenografts, researchers demonstrated that nab-paclitaxel depleted the stroma surrounding pancreatic tumors and thus was able to facilitate delivery of gemcitabine more effectively. Those treated with the combination had a gemcitabine concentration in tumors that was 3.7-fold higher than that seen with gemcitabine alone.Citation104 SPARC is, therefore, emerging as an important biomarker of response to nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy in this disease.

CP-4126: gemcitabine evolved

The human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 and human concentrative nucleoside transporter 1 and 3 are responsible for gemcitabine uptake into tumor cells. Lack of these transporters denotes a poorer prognosis with adjuvant treatment and predicts for resistance to therapy.Citation105 A promising new nucleoside analog that bypasses this mechanism has shown some benefit in refractory solid tumors in phase I trials, including stabilization of disease in some patients with pancreatic cancer. Though a derivative of gemcitabine, CP-4126 does not require nucleoside transporters.Citation106 This agent is currently entering phase II trials.

Vaccine trials: new techniques hold promise

In 2002, dendritic cells derived from peripheral blood monocytes were transfected with human tumor antigen mucin (MUC1) to be used as a vaccine for advanced breast, pancreatic, or papillary cancer. In this phase I trial, it was demonstrated that immune responses could be induced in 4 of 10 patients, but only 1 patient with a response had observed benefit. Despite lack of efficacy, treatment was regarded as safe.Citation107 The same year, a phase I/II trial using dl1520, a gene-deleted replication-selective adenovirus that targets malignant cells, was delivered by endoscopic ultrasound in combination with gemcitabine in locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Though this was also deemed safe with only small elevations of pancreatic enzymes and no pancreatitis, the effect was modest with 20% RR and another 38% SD.Citation108 One complete remission of liver metastasis of pancreatic cancer refractory to gemcitabine was reported.Citation109 Encouragingly, a recent a phase I trial with peptide vaccine for VEGFR2 using the epitope peptide VGFR2-169 in combination of gemcitabine shows promising results in advanced pancreatic cancer. The control rate was 67% with a OS of 8.7 months with 1 PR and 11 patients (61%) with SD.Citation110 Clearly, this is an evolving field in which more study is needed, and trials are ongoing, including a trial of endoscopically-guided intratumoral injections, as intratumoral injections have been demonstrated to generate an enhanced systemic tumor-specific immune response in a preclinical model.Citation111

Summary

Despite improved surgical outcomes and advances in chemotherapy and radiation therapy, overall 5-year survival of pancreatic cancer is approximately 5%.Citation112 Although complete surgical resection offers the only chance for long-term survival, the majority of patients who undergo surgery with curative intent will eventually succumb to the disease.Citation3

A multidisciplinary approach with CRT holds the promise of downstaging a locally advanced cancer and sterilizing the perivascular neoplastic tissue and even distant micrometastatic disease and results in a survival advantage as compared with unresected patients. Although the optimal regimen has not been identified, there is strong phase II evidence that full-dose gemcitabine can be tolerated in combination with adequate radiation, and this dose is theoretically most likely to address micrometastatic disease outside of the radiation field. There appears to be a trend toward higher RRs with gemcitabine-based CRT that must be confirmed in multicenter trials.Citation38,Citation113–Citation115

In metastatic disease, chemotherapy is an important component of a multidisciplinary approach to palliative care, which must be supported by pain management and nutrition. Gemcitabine has been considered the standard treatment for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer ever since Burris et alCitation4 demonstrated a modest, yet statistically significant, improvement in OS and a significant clinical benefit for gemcitabine chemotherapy compared with 5-FU. However, single-agent gemcitabine in multiple trials consistently only achieves median OS figures of approximately 6 months, a finding that clearly indicates the need for the development of new treatment strategies.Citation116 Phase I and phase II trials of a variety of gemcitabine-based combinations have demonstrated promising activity. Invariably, when these have been evaluated in randomized phase III trials compared with single-agent gemcitabine, the results have been disappointing.

The conclusive results of ECOG-6201 establish that adding oxaliplatin to gemcitabine is not an appropriate standard of care for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.Citation74 Some meta-analyses, however, have found that overall RRs were significantly improved by gemcitabine-based combination therapy with a platinumCitation80,Citation81 or fluoropyrimidine,Citation80 particularly in patients with good performance status. Other combination therapies have shown promise in improving the RR, eg, a phase III study of the combination of irinotecan with gemcitabine vs gemcitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer, with a primary end point of survival, a statistically significant improvement in RR was found although the primary end point of survival was not reached.Citation117 Similarly, the GERCOR trial demonstrated an improved RR with the addition of oxaliplatin to gemcitabine,Citation76 a benefit not seen in the larger ECOG trial.Citation74

The possibility of improved RR with combination therapy, however, does raise the question: would combination therapy be worth examining in the neoadjuvant setting, where RR dictates the possibility of future resection?

In future trials, it will be important to stratify patients by modern criteria for resectability to elucidate the benefit of our therapies. Most neoadjuvant trials have grouped together: patients with borderline resectable, resectable, and borderline unresectable disease. Most chemotherapy trials have treated as one group: patients with unresectable locally advanced disease, recurrent disease, and metastatic disease. There is increasing evidence that the prognosis is different in these stages of disease,Citation118 although micrometastasis may already present in most patients. We are doing the research process and our patients a disservice if we do not stratify the patients in our trials by modern criteria. Trials of innovative technology, such as vaccines, should pay particular attention to the characteristics of patients’ disease.

Some of the most interesting current research seeks to differentiate which patients will respond to therapy. As evidenced by the relatively low RRs with gemcitabine, better biological markers to help predict response are urgently needed if we are to make progress in this disease.

Acknowledgments and disclosure

The authors reports no conflicts of interest in this work. The authors also thank Dana Herrigel, MD, Maureen Huhmann, DCn, RD, CS, Imran Khan, MD, and Samuel SH Wang, PhD.

References

- JanesRHJrNiederhuberJEChmielJSNational patterns of care for pancreatic cancer. Results of a survey by the Commission on CancerAnn Surg199622332612728604906

- CalleEERodriguezCWalker-ThurmondKThunMJOverweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adultsN Engl J Med2003348171625163812711737

- ShaibYDavilaJNaumannCEl-SeragHThe impact of curative intent surgery on the survival of pancreatic cancer patients: a U.S. Population-based studyAm J Gastroenterol200710271377138217403071

- BurrisHAIIIMooreMJAndersenJImprovements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trialJ Clin Oncol1997156240324139196156

- KastrinosFMukherjeeBTayobNRisk of pancreatic cancer in families with Lynch syndromeJAMA2009302161790179519861671

- FerroneCRLevineDATangLHBRCA germline mutations in Jewish patients with pancreatic adenocarcinomaJ Clin Oncol200927343343819064968

- BaoYMichaudDSPhysical activity and pancreatic cancer risk: a systematic reviewCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev200817102671268218843009

- MichaudDSGiovannucciEWillettWCColditzGAStampferMJFuchsCSPhysical activity, obesity, height, and the risk of pancreatic cancerJAMA2001286892192911509056

- LiDMorrisJSLiuJBody mass index and risk, age of onset, and survival in patients with pancreatic cancerJAMA2009301242553256219549972

- GumbsAAObesity, pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancerObes Surg20081891183118718563497

- SmeenkHGTranTCErdmannJvan EijckCHJeekelJSurvival after surgical management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: does curative and radical surgery truly exist?Langenbecks Arch Surg200539029410315578211

- MuDQPengSYWangGFRisk factors influencing recurrence following resection of pancreatic head cancerWorld J Gastroenterol200410690690915040043

- ShibataKMatsumotoTYadaKSasakiAOhtaMKitanoSFactors predicting recurrence after resection of pancreatic ductal carcinomaPancreas2005311697315968250

- AbramsRALowyAMO’ReillyEMWolffRAPicozziVJPistersPWCombined modality treatment of resectable and borderline resectable pancreas cancer: expert consensus statementAnn Surg Oncol20091671751175619390900

- KalserMHEllenbergSSPancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resectionArch Surg198512088999034015380

- KlinkenbijlJHJeekelJSahmoudTAdjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative groupAnn Surg1999230677678210615932

- GarofaloMCRegineWFTanMTOn statistical reanalysis, the EORTC trial is a positive trial for adjuvant chemoradiation in pancreatic cancerAnn Surg2006244233233316858208

- NeoptolemosJPStockenDDFriessHfor the European Study Group for Pancreatic CancerA randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancerN Engl J Med2004350121200121015028824

- ChotiMAdjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer – the debate continuesN Engl J Med2004350121249125115028829

- CraneCHBen-JosefESmallWJrChemotherapy for pancreatic cancerN Engl J Med2004350262713271515218575

- KosugeTKiuchiTMukaiKKakizoeTfor the Japanese Study Group of Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer (JSAP)A multicenter randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effect of adjuvant cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil therapy after curative resection in cases of pancreatic cancerJpn J Clin Oncol200636315916516490736

- OettleHPostSNeuhausPAdjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2007297326727717227978

- UenoHKosugeTMatsuyamaYA randomised phase III trial comparing gemcitabine with surgery-only in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: Japanese Study Group of Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic CancerBr J Cancer2009101690891519690548

- NeoptolemosJBüchlerMStockenDDESPAC-3(v2): A multicenter, international, open-label, randomized, controlled phase III trial of adjuvant 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid (5-FU/FA) versus gemcitabine (GEM) in patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. ASCO Annual MeetingJ Clin Oncol200927Suppl 18 Abstract LBA4505.

- VaradhacharyGRTammEPAbbruzzeseJLBorderline resectable pancreatic cancer: definitions, management, and role of preoperative therapyAnn Surg Oncol20061381035104616865597

- UjikiMBTalamontiMSGuidelines for the surgical management of pancreatic adenocarcinomaSemin Oncol200734431132017674959

- WhiteRRHurwitzHIMorseMANeoadjuvant chemoradiation for localized adenocarcinoma of the pancreasAnn Surg Oncol200181075876511776488

- AmmoriJBCollettiLMZalupskiMMSurgical resection following radiation therapy with concurrent gemcitabine in patients with previously unresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreasJ Gastrointest Surg20037676677213129554

- JessupJMSteeleGJrMayerRJNeoadjuvant therapy for unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinomaArch Surg199312855595648098206

- PilepichMVMillerHHPreoperative irradiation in carcinoma of the pancreasCancer Biol Ther198046919451949

- BrunnerTBGrabenbauerGGBaumUHohenbergerWSauerRAdjuvant and neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy in ductal pancreatic carcinomaStrahlenther Onkol2000176626527310897253

- WeeseJLNussbaumMLPaulARIncreased resectability of locally advanced pancreatic and periampullary carcinoma with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapyInt J Pancreatol199071–31771852081923

- MassuccoPCapussottiLMagninoAPancreatic resections after chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced ductal adenocarcinoma: analysis of perioperative outcome and survivalAnn Surg Oncol20061391201120816955382

- BrownKMSiripurapuVDavidsonMChemoradiation followed by chemotherapy before resection for borderline pancreatic adenocarcinomaAm J Surg2008195331832118308038

- WilkowskiRThomaMBrunsCWagnerAHeinemannVChemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine and continuous 5-FU in patients with primary inoperable pancreatic cancerJOP20067434936016832132

- TalamontiMSSmallWJrMulcahyMFA multi-institutional phase II trial of preoperative full-dose gemcitabine and concurrent radiation for patients with potentially resectable pancreatic carcinomaAnn Surg Oncol200613215015816418882

- IokaTTanakaSNakaizumiANishiyamaKA phase I trial of chemoradiation therapy with concurrent full dose gemcitabine for unresectable locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinomaJ Clin Oncol2005231654209

- SmallWJrBJFreedmanGMFull-dose gemcitabine with concurrent radiation therapy in patients with nonmetastatic pancreatic cancer: a multicenter phase II trialJ Clin Oncol200826694294718281668

- RegineWFWinterKAAbramsRAFluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trialJAMA200829991019102618319412

- LoehrerPJPowellMECardenesHRA randomized phase III study of gemcitabine in combination with radiation therapy versus gemcitabine alone in patients with localized, unresectable pancreatic cancer: E4201J Clin Oncol200826Suppl 20 Abstract 4506.

- MartiJLHochesterHSHiotisSPDonahueBRyanTNewmanEPhase I/II trial of induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy and surgery for locoregionally advanced pancreatic cancerAnn Surg Oncol200815123521353118830756

- ChauffertBMornexFBonnetainFPhase III trial comparing intensive induction chemoradiotherapy (60 Gy, infusional 5-FU and intermittent cisplatin) followed by maintenance gemcitabine with gemcitabine alone for locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. Definitive results of the 2000–01 FFCD/SFRO studyAnn Oncol20081991592159918467316

- WhiteRRXieHBGottfriedMRSignificance of histological response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy for pancreatic cancerAnn Surg Oncol200512321422115827813

- PedduPQuagliaAKanePAKaraniJBRole of imaging in the management of pancreatic massCrit Rev Oncol Hematol2009701122318951813

- TammECharnsangavejCSzklarukJAdvanced 3-D imaging for the evaluation of pancreatic cancer with multidetector CTInt J Gastrointest Cancer2001301–2657112489581

- MaiseyNRWebbAFluxGDFDG-PET in the prediction of survival of patients with cancer of the pancreas: a pilot studyBr J Cancer200083328729310917540

- MercadanteSNicosiaFCeliac plexus block: a reappraisalReg Anesth Pain Med199823137489552777

- SakorafasGHTsiotouAGSarrMGIntraoperative celiac plexus block in the surgical palliation for unresectable pancreatic cancerEur J Surg Oncol199925442743110419716

- EisenbergECarrDBChalmersTCNeurolytic celiac plexus block for treatment of cancer pain: A meta-analysisAnesth Analg1995822902957818115

- LillemoeKDCameronJLKaufmanHSChemical splanchnicectomy in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a prospective randomized trialAnn Surg199321754474557683868

- MatsumotoJTraversoLWExocrine function following the whipple operation as assessed by stool elastaseJ Gastrointest Surg20061091225122917114009

- PerezMMNewcomerADMoertelCGGoVLDimagnoEPAssessment of weight loss, food intake, fat metabolism, malabsorption, and treatment of pancreatic insufficiency in pancreatic cancerCancer19835223463526305473

- BrunoMJHaverkortEBTijssenGPPlacebo controlled trial of enteric coated pancreatin microsphere treatment in patients with unresectable cancer of the pancreatic head regionGut19984292969505892

- BachmannJKettererKMarschCPancreatic cancerrelated cachexia: influence on metabolism and correlation to weight loss and pulmonary functionBMC Cancer200928925519635171

- RobinsonDWJrEisenbergDFCellaDZhaoNde BoerCDeWitteMThe prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in pancreatic cancer cachexiaJ Support Oncol20086628329018724539

- HeiskanenTMatzkeSHaakanaSGergovMVuoriEKalsoETransdermal fentanyl in cachectic cancer patientsPain20091441–221822219442446

- MannCDThomassetSCJohnsonNACombined biliary and gastric bypass procedures as effective palliation for unresectable malignant diseaseANZ J Surg200979647147519566872

- CanBSarayACaglikulekçiMSaranYEffects of obstructive jaundice on the peripheral nerve: an ultrastructural study in ratsEur Surg Res200436422623315263828

- CostamagnaGPandolfiMEndoscopic stenting for biliary and pancreatic malignanciesJ Clin Gastroenterol200438596714679329

- BallingerABMcHughMCatnachSMSymptom relief and quality of life after stenting for malignant bile duct obstructionGut1994354674707513672

- TibbleJACairnsSRRole of endoscopic endoprostheses in proximal malignant biliary obstructionJ Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg20018211812311455466

- SukKTKimHSKimJWRisk factors for cholecystitis after metal stent placement in malignant biliary obstructionGastrointest Endosc200664452252916996343

- MossACMorrisEMac MathunaPPalliative biliary stents for obstructing pancreatic carcinomaCochrane Database Syst Rev20062CD004200

- PovoskiSPKarpehMSJrConlonKCBlumgartLHBrennanMFAssociation of preoperative biliary drainage with postoperative outcome following pancreaticoduodenectomyAnn Surg1999230213114210450725

- SohnTAYeoCJCameronJLPittHALillemoeKDDo preoperative biliary stents increase postpancreaticoduodenectomy complications?J Gastrointest Surg200043258267 discussion 267–258.10769088

- HochwaldSNBurkeECJarnaginWRFongYBlumgartLHAssociation of preoperative biliary stenting with increased postoperative infectious complications in proximal cholangiocarcinomaArch Surg1999134326126610088565

- MumtazKHamidSJafriWEndoscopic retrograde cholangiopan-creaticography with or without stenting in patients with pancreaticbiliary malignancy, prior to surgeryCochrane Database Syst Rev20073CD00600117636818

- MallinsonCNRakeMOCockingJBChemotherapy in pancreatic cancer: results of a controlled, prospective, randomised, multicentre trialBr Med J19802816255158915917004559

- KelsenDHudisCNiedzwieckiDA phase III comparison trial of streptozotocin, mitomycin, and 5-fluorouracil with cisplatin, cytosine arabinoside, and caffeine in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinomaCancer19916859659691833042

- CullinanSMoertelCEWieandHSA phase III trial on the therapy of advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Evaluations of the Mallinson regimen and combined 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cisplatinCancer19906510220722122189551

- FungMCIshiguroHTakayamaSMorizaneTAdachiSSakataTSurvival benefit of chemotherapy treatment in advanced pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysisProc Am Soc Clin Oncol2003221155

- GrunewaldRKantarjianHKeatingMJAbbruzzeseJTarassoffPPlunkettWPharmacologically directed design of the dose rate and schedule of 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine (Gemcitabine) administration in leukemiaCancer Res19905021682368262208147

- TemperoMPlunkettWRuiz Van HaperenVRandomized phase II comparison of dose-intense gemcitabine: thirty-minute infusion and fixed dose rate infusion in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinomaJ Clin Oncol200321183402340812885837

- PoplinEFengYBerlinJPhase III, randomized study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine (fixed-dose rate infusion) compared with gemcitabine (30-minute infusion) in patients with pancreatic carcinoma E6201: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology GroupJ Clin Oncol200927233778378519581537

- LouvetCAndrèTLledoGGemcitabine combined with oxaliplatin in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: final results of a GERCOR multicenter phase II studyJ Clin Oncol2002201512151811896099

- LouvetCLabiancaRHammelPGemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trialJ Clin Oncol200523153509351615908661

- ColucciGLabiancaRDi CostanzoFA randomized trial of gemcitabine (G) versus G plus cisplatin in chemotherapy-naive advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: The GIP-1 (Gruppo Italiano Pancreas – GOIM/GISCAD/GOIRC) study. 2009 ASCO Annual MeetingJ Clin Oncol200927Suppl 15 Abstract 4504.

- NietoJGrossbandMLKozuchPMetastatic pancreatic cancer 2008: is the glass less empty?Oncologist200813556257618515741

- MooreMJGoldsteinDHammJErlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials GroupJ Clin Oncol2007251960196617452677

- HeinemannVBoeckSHinkeALabiancaRLouvetCMeta-analysis of randomized trials: evaluation of benefit from gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy applied in advanced pancreatic cancerBMC Cancer200888218373843

- HeinemannVLabiancaRHinkeALouvetCIncreased survival using platinum analog combined with gemcitabine as compared to single-agent gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: pooled analysis of two randomized trials, the GERCOR/GISCAD intergroup study and a German multicenter studyAnn Oncol200718101652165917660491

- WangXNiQJinMGemcitabine or gemcitabine plus cisplatin for in 42 patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancerZhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi200224440440712408777

- ColucciGGiulianiFGebbiaVGemcitabine alone or with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic pancreatic carcinoma: a prospective, randomized phase III study of the Gruppo Oncologia dell’Italia MeridionaleCancer200294490291011920457

- Xie deRLiangHLWangYGuoSSMeta-analysis of inoperable pancreatic cancer: gemcitabine combined with cisplatin versus gemcitabine aloneChin J Dig Dis200671495416412038

- CartwrightTHCohnAVarkeyJAPhase II study of oral capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol20022016016411773165

- HerrmannRBodokgGRuhstallerTGemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology GroupJ Clin Oncol200725162212221717538165

- XiongHQRosenbergALoBuglioACetuximab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor, in combination with gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer: a multicenter phase II trialJ Clin Oncol200422132610261615226328

- OettleHPetzerUStielerJOxaliplatin/Folinic acid/5-fluoroouracil [24h] (OFF) plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone (BSC) in second-line therapy of gemcitabine-refractory advanced pancreatic cancer (CONKO-003)Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol2005 Abstract 4031.

- StrimpakosASaifMWSyrigosKNPancreatic cancer: from molecular pathogenesis to targeted therapyCancer Metastasis Rev200827349552218427734

- IannittiDDipetrilloTAkemanPErlotinib and chemoradiation followed by maintenance erlotinib for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: A phase I studyAm J Clin Oncol20052857057516317266

- EpelbaumRSchnaiderJGluzmanAErlotinib as a single-agent therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancerPresented at: the ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancer symposium2007Orlando, Florida

- KulkeMHBlaszkowskyLSRyanDPCapecitabine plus erlotinib in gemcitabine-refractory advanced pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol200725304787479217947726

- PhilipPAMooneyMJaffeDConsensus report of the National Cancer Institute clinical trials planning meeting on pancreas cancer treatmentJ Clin Oncol200927335660566919858397

- BurtnessBAPowellMBerlinJPhase II trial of irinotecan/docetaxel for advanced pancreatic cancer with randomization between irinotecan/docetaxel and irinotecan/docetaxel plus C225, a monoclonal antibody to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-r) : Eastern Cooperative Oncology [Meeting Abstracts]J Clin Oncol200725Suppl 18451917925545

- KindlerHLFribergGSinghDAPhase II trial of bevacizumab plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol200523318033804016258101

- KindlerHLNiedzwieckiDHollisDA double-blind, placebo controlled randomized phase III gemcitabine + bevacisumab versus gemcitabien versus placeboJ Clin Oncol200725185450817906219

- WallaceJALockerGNattamSSorafenib plus gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase II trial of the University of Chicago phase II consortiumJ Clin Oncol200725S 224

- O’ReillyEMNiedzwieckiDHollisDRA phase II trial of sunitinib (S) in previously-treated pancreas adenocarcinoma (PAC), CALGB 80603ASCO Annual Meeting2008

- BruneKHongSMLiAGenetic and epigenetic alterations of familial pancreatic cancersCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev200817123536354219064568

- PietrasKRubinKSjoblomTInhibition of PDGF receptor signaling in tumor stroma enhances antitumor effect of chemotherapyCancer Res200262195476548412359756

- MantoniTSSchendelRRRödelFStromal SPARC expression and patient survival after chemoradiation for non-resectable pancreatic adenocarcinomaCancer Biol Ther2008711 [Epub ahead of print].

- HwangRFMooreTArumugamTCancer-associated stromal fibroblasts promote pancreatic tumor progressionCancer Res200868391892618245495

- Von HoffDDRamanathanRBoradMSPARC correlation with response to gemcitabine (G) plus nab-paclitaxel (nab-P) in patients with advanced metastatic pancreatic cancer: A phase I/II study. ASCO Annual MeetingJ Clin Oncol200927Suppl 15 Abstract 4525.

- MaitraANab-paclitaxel targets tumor stroma and results, combined with gemcitabine, in high efficacy against pancreatic cancer modelsAACR20091117C246

- MaréchalRMackayJRLaiRHuman equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 and human concentrative nucleoside transporter 3 predict survival after adjuvant gemcitabine therapy in resected pancreatic adenocarcinomaClin Cancer Res20091582913291919318496

- BergmanAMAdemaABalzariniJAntiproliferative activity, mechanism of action and oral antitumor activity of CP-4126, a fatty acid derivative of gemcitabine, in in vitro and in vivo tumor modelsInvest New Drugs2010112 [Epub ahead of print].

- PecherGHaringAKaiserLThielEMucin gene (MUC1) transfected dendritic cells as vaccine: results of a phase I/II clinical trialCancer Immunol Immunother20025111–1266967312439613

- HechtJRBedfordRAbbruzzeseJLA phase I/II trial of intratumoral endoscopic ultrasound injection of ONYX-015 with intravenous gemcitabine in unresectable pancreatic carcinomaClin Cancer Res20039255556112576418

- WobserMKeikavoussiPKunzmannVWeiningerMAndersenMHBeckerJCComplete remission of liver metastasis of pancreatic cancer under vaccination with a HLA-A2 restricted peptide derived from the universal tumor antigen survivinCancer Immunol Immunother200655101294129816315030

- MiyazawaMOhsawaRTsunodaTPhase I clinical trial using peptide vaccine for human vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in combination with gemcitabine for patients with advanced pancreatic cancerCancer Sci2010101243343919930156

- YangASMonkenCELattimeECIntratumoral vaccination with vaccinia-expressed tumor antigen and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor overcomes immunological ignorance to tumor antigenCancer Res200363206956696114583497

- JemalASiegelRWardECancer statistics, CACancer J Clin20085827196

- BudihartoTHaustermansKVan CutsemEA phase I radiation dose-escalation study to determine the maximal dose of radiotherapy in combination with weekly gemcitabine in patients with locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinomaRadiat Oncol200833018808686

- CraneCHAJEvansDBIs the therapeutic index better with gemcitabine-based chemoradiation than with 5-fluorouracil-based chemoradiation in locally advanced pancreatic cancer?Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys20025251293130211955742

- McGinnCJZalupskiMMRadiation therapy with once-weekly gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer: current status of clinical trialsInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys200356Suppl 4S10S15

- TaberneroJMacarullaTChanging the paradigm in conducting randomized clinical studies in advanced pancreatic cancer: an opportunity for better clinical developmentJ Clin Oncol200927335487549119858387

- Rocha LimaCMGreenMRRotcheRIrinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rateJ Clin Oncol200422183776378315365074

- HashimotoKUenoHIkedaMDo recurrent and metastatic pancreatic cancer patients have the same outcomes with gemcitabine treatment?Oncology2009773–421722319729980

- BakkevoldKEArnesjoBDahlOKambestadBAdjuvant combination chemotherapy (AMF) following radical resection of carcinoma of the pancreas and papilla of Vater--results of a controlled, prospective, randomised multicentre studyEur J Cancer199329A56987038471327

- YeungRSWeeseJLHoffmanJPNeoadjuvant chemoradiation in pancreatic and duodenal carcinoma. A phase II studyCancer1993727212421338374871

- KamthanAGMorrisJCDaltonJCombined modality therapy for stage II and stage III pancreatic carcinomaJ Clin Oncol1997158292029279256136

- WhiteRLeeCAnscherMPreoperative chemoradiation for patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreasAnn Surg Oncol199961384510030414

- BajettaEDi BartolomeoMStaniSCChemoradiotherapy as preoperative treatment in locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer patients: results of a feasibility studyInt J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys199945228528910487547

- WaneboHJGlicksmanASVezeridisMPPreoperative chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical resection of locally advanced pancreatic cancerArch Surg20001351818710636353

- KimHJCzischkeKBrennanMFConlonKCDoes neoadjuvant chemoradiation downstage locally advanced pancreatic cancer?J Gastrointest Surg20026576376912399067

- RauHGWichmannMWWilkowskiRSurgical therapy of locally advanced and primary inoperable pancreatic carcinoma after neoadjuvant preoperative radiochemotherapyChirurg200273213213711974476

- AristuJCanonRPardoFSurgical resection after preoperative chemoradiotherapy benefits selected patients with unresectable pancreatic cancerAm J Clin Oncol2003261303612576921

- WilkowskiRThomaMSchauerRWagnerAHeinemannVEffect of chemoradiotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin on locoregional control in patients with primary inoperable pancreatic cancerWorld J Surg10200428101011101815573257

- Sa CunhaARaultALaurentCAdhouteXVendrelyVBéllannéeGBrunetRColletDMassonBSurgical resection after radiochemotherapy in patients with unresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreasJ Am Coll Surg2005201335936516125068

- DelperoJRTurriniOLocally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Chemoradiotherapy, reevaluation and secondary resectionCancer Radiother2006106–746247016987678

- AdhouteXSmithDVendrelyVSubsequent resection of locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma after chemoradiotherapyGastroenterol Clin Biol200630222423016565654

- TinklDGrabenbauerGGGolcherHDownstaging of pancreatic carcinoma after neoadjuvant chemoradiationStrahlenther Onkol2009185557–6655756619756421

- BerlinJDCatalanoPThomasJPKuglerJWHallerDGBensonABIIIPhase III study of gemcitabine in combination with fluorouracil versus gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial E2297J Clin Oncol200220153270327512149301

- ReissHHelmANiedergethmannMSchmidt-WolfIMoikMHammerCA randomized, prospective, multicenter, phase III trial of gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), folinic acid vs gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. ASCO Annual MeetingJ Clin Oncol200523Suppl 16 Abstract LBA4009.

- CunninghamDChauIStockenDDPhase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine versus gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol200927335513551819858379

- HeinemannVQuietzschDGieselerFRandomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol2006242439463952

- StathopoulosGPSyrigosKAravantinosGA multicenter phase III trial comparing irinotecan-gemcitabine (IG) with gemcitabine (G) monotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancerBr J Cancer200695558759216909140

- Abou-AlfaGKLetourneauRHarkerGRandomized phase III study of exatecan and gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in untreated advanced pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol200624274441444716983112

- ReniMCordioSMilandriCGemcitabine versus cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil, and gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trialLancet Oncol20056636937615925814

- OettleHRichardsDRamanathanRKA phase III trial of pemetrexed plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine in patients with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancerAnn Oncol200516101639164516087696

- BramhallSRRosemurgyABrownPDBowryCBuckelsJAMarimastat as first-line therapy for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized trialJ Clin Oncol200119153447345511481349

- BramhallSRSchultzJNemunaitisJBrownPDBailletMBuckelsJAA double-blind placebo-controlled, randomised study comparing gemcitabine and marimastat with gemcitabine and placebo as first line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancerBr J Cancer200287216116712107836

- MooreMJHammJDanceyJComparison of gemcitabine versus the matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor BAY 12-9566 in patients with advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials GroupJ Clin Oncol200321173296330212947065

- Van CutsemEvandeVeldeKarasekPPhase III trial of gemcitabine plus tipifarnib compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced pancreatic cancerJ Clin Oncol20042281430143815084616