Abstract

Objective:

Based on the present authors’ research and several approaches to grief related to loss by death and nonmalignant chronic pain, the paper suggests a new integrated theoretical framework for intervention in clinical settings.

Methods:

An open qualitative review of the literature on grief theories was performed searching for a new integrated approach in the phenomenological tradition. We then investigated the relationship between grief, loss and chronic nonmalignant pain, looking for main themes and connections and how these could be best understood in a more holistic manner.

Results:

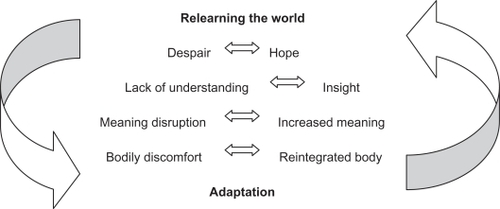

Two main themes were formulated, “relearning the world” and “adaptation”. Between these themes a continuous movement emerged involving experience such as: “despair and hope”, “lack of understanding and insight”, “meaning disruption and increased meaning”, and “bodily discomfort and reintegrated body”. These were identified as paired subthemes.

Conclusions:

Grief as a distinctive experience means that health care must be aimed at each individual experience and situation. Grief experience and working with grief are considered in terms of relearning the world while walking backwards and living forwards, as described in our integrated model. We consider that this theoretical framework regarding grief should offer an integrated foundation for health care workers who are working with people experiencing grief caused by death or chronic pain.

Keywords:

Background

Grief caused by death or chronic nonmalignant pain may be understood as a personal and fundamental experience carrying many meanings, which may be revealed by emotional, cognitive, behavioral and bodily manifestations and expressions. Loss is a life experience which concerns something irrevocable and feelings connected to what is lost. Grief caused by loss is naturally integrated in the human experience, but sometimes unfolds itself in ways which are difficult to define. Loss related to grief is not just about death, but can include a number of situations. It may also be related to loss caused by chronic pain, impaired health, loss of work or social relations.Citation1 Unlike loss caused by death, many losses associated with chronic illness can be recovered or partly recovered.Citation2 Parkes has confirmed that any significant loss, regardless of its origin, has the potential for creating a similar pathway for grief recovery comparable to the experience of loss by death.Citation3 With chronic pain, loss and ensuring grief may be less obvious, even to health care workers in pain clinics.Citation4 There seems to be little recognition of the differences and similarities between grief and loss associated with death and chronic pain. Furthermore, intervention strategies in helping patients with loss related to chronic pain, which often accompanies chronic illness, are rarely reported.Citation2

Traditionally, pain has been described in biomedical terms as a neurophysiological state. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”.Citation5 Following this definition, pain is a complex, multidimensional and subjective phenomenon. Thus explaining and understanding pain must incorporate a subjective experience and a phenomenological dimension where loss and grief are integral parts.Citation6 For some patients, the fear of being incapacitated because of pain may be similar to their fear of death.Citation7 Loss of someone close may also be described as a painful experience. Therefore, experiencing loss and grief caused by chronic pain and death of someone close, might have much in common. As such, chronic pain may be naturally related to loss and grief, and at the same time loss and grief may be naturally related to chronic pain. Thus, knowledge within each tradition may overlap and be of help when understanding these life phenomena.

Clinical understanding of grief is undergoing a fundamental change. From its origin in Freudian roots, there is a shift towards a social-psychological perspective. According to classic grief theory, grief and grief work are considered limited in time. Grief work is also considered successful when the “bereaved” or the “sufferer” is freed from the ties to what is lost.Citation3,Citation8–Citation9 However, more recent grief theory emphasizes the positive value of these ties as a source to further enrichment of life.Citation10–Citation11 According to the present authors, understanding how each individual experiences grief, is fundamental to health care workers generally to maintain a deeper understanding of the grief situation. Loss and grief are part of life itself and are closely connected, and may be revealed in different life situations. In an integrated framework, the assumption is that we exist in the world as whole bodies and everything will influence the person as a whole body.Citation12

This is the background for our work where the aim is to suggest a new integrated theoretical framework for intervention in clinical settings related to grief and loss caused by death of someone close and chronic nonmalignant pain.

Methods

In the literature review, the focus is to understand grief related to several types of loss and reveal the specific characteristics of these phenomena. Initially, an open qualitative methodological approach was chosen. Several steps were followed systematically:

An open qualitative review was done to gain a broad perspective on grief and grief theories by identifying common features and traditions.

We investigated the relationship between grief, loss and chronic pain looking for substance and connections and how these could be best understood in a more holistic manner.

Categories were identified and discussed, and were finally specified in paired subthemes.

Finally, an abstraction of the subthemes was done searching for overall themes in a dynamic relationship.

Results

According to our new understanding of chronic pain, grief and grief work, four subthemes were identified and formulated. These subthemes were experiences such as: “despair and hope”, “lack of understanding and insight”, “meaning disruption and increased meaning”, and “bodily discomfort and reintegrated body”, described as paired subthemes in a continuous movement. Two main themes were identified and formulated as “relearning the world” and “adaptation”. Between these main themes there exists a circular process as well as a vertical process binding the subthemes and main themes together ().

Discussion

The aim of this paper is to suggest an integrated approach for intervention in clinical settings where phenomena such as grief, loss and chronic pain are present. The discussion considers the movement between the main themes “relearning the world” and “adaptation” and paired sub-themes and leads to an integrated theoretical framework ().

An integrated theoretical framework on grief

Independent of its origin, grief is considered by the present authors as a life phenomenon. This means that each person experiences, interprets and understands grief in a unique way. As such, it seems unreasonable to limit grief to a distinct definition or a defined course.Citation13 Contrary to classic grief theory stating the grief process to be limited in time and following stages, more recent grief theory emphasizes that the grief process follows the individual person. From a phenomenological perspective these experiences vary in form and complexity. This perspective to grief inevitably involves the whole life situation. It means that grief is existence and touches everything in the experienced life situation. Furthermore, it involves moving into a changed life world with new experiences and ways of meeting the world.Citation13

Life phenomena like grief and loss are fundamental experiences. These phenomena are typical of human life, although they are expressed differently and uniquely.Citation14 The philosopher Lipps (referred to by Pahuus) argues that to exist is to adopt an attitude in the situation and be moved bodily.Citation15 This challenging movement in grief work involves an optimal adjustment and hope for the future life situation. Here the overall process is expressed by a movement between “relearning the world” and “adaptation”. This insight is fundamental for a person who has experienced loss caused by death of a close person as well as loss caused by chronic pain, where the grieving person might need support in this process. According to our findings, relearning the world and adaptation consists of a continuous movement involving experiences like: “despair – hope”, “lack of understanding – insight”, “meaning disruption – creating meaning”, and “bodily discomfort – reintegrated body”. This also involves continuous movements along each of these continua as well as in between each experience (sub-themes), as illustrated in . Here the continuous movements mean a sequence of experiences of similar type in which the different experiences vary in strength and endurance.

Despair–Hope

Grief is a fundamental experience and carries meaning which is particular to the grieving person. Despair is an expression of lack of meaning and discontinuity in life. One can also say that despair is a multifaceted experience and encompasses grief expressions such as fright, guilt, loneliness, indifference, anger and emptiness.Citation13 These expressions may vary in strength and duration. If we look at grief as a predictable reaction and a process passing through several phases, as described in classic grief theories, it may increase a feeling of despair. Instead, there is a need to grasp the unique experience of each person where flexibility is required. Chronic pain is associated with a variety of life issues causing despair, and the pattern of despair often includes personal stress, psychological disturbances such as depression, maladaptive and dysfunctional behavior and social isolation.Citation16 Thus, the patients involved often experience a vicious circle where one symptom leads to the other and loss of hope may lead to unbearable suffering.Citation17

The grieving person has to be seen in his or her situation of despair. However, to be seen and understood is not exactly the same at any point in time, as the experienced life situation is often unpredictable and varies. The despair–hope continuum is also influenced by other components described in our model (). The opposite of despair, the phenomenon of hope is a state of being. It is future oriented and thus is essential for adaptation. Hope includes an optimistic and positive attitude towards the future.Citation18 Independent of the original cause, several elements in grief work are to create hope through expressing grief, what is lost, acknowledging it, and maintaining ties to what is lost.Citation13 To maintain hope in the presence of chronic pain means that chronic pain must be put in the background and those enjoyable goal pursuits of life must be put in the front of consciousness.Citation1 Viewing the world from a new life situation is like walking backwards and living forwards on the “despair–hope” continuum. This adaptive movement is future oriented with a hope for a meaningful life.

Lack of understanding – Insight

Grief may disrupt continuity and confront the sufferer with vulnerability leading to decreased understanding and losing part of his or her self. Furthermore, the situation often limits the person’s concentration, sensuality and cognition. When the ties to the loved one or present life are disrupted, the person will experience new challenges that force new insights.Citation13 This means that the bereaved person has to relearn themselves in the world. A major challenge that many patients with chronic pain problems face, is their confusion and decreased understanding with regard to the nature and extent of their losses.Citation2 This may be rooted in the fact that many of the losses are not temporary, and that they often increase over time as the situation gets worse. The patients may become unable to maintain their previous levels of functioning and previous roles. In the face of such unpredictable situations, it is impossible to know what losses may occur and when they may happen.Citation2 Support and help has to emphasize awareness of these losses, and at the same time encourage the abilities and resources that are available for that person.Citation19

A positive focus is important in reorganization and adjustment.Citation20 To make room for the grief conceptualization is of great importance. Expressing grief and becoming aware of the loss is an important part of self-understanding.Citation13 Furthermore, this means that expressing and narrating grief experiences will contribute to new insight.Citation13,Citation21 This is also supported by Dysvik,Citation22 where the patients studied in a pain management program, expressed a number of pain-related losses and saw the value of expressing them. In this way the grieving person in pain may discover new perspectives and connections which may contribute to coping and adaptation to an altered life situation.Citation22 BrattbergCitation23 emphasizes how important it is for pain patients to realize that they are in a grief situation, and that they must find out what the grief experience consists of. As such, understanding pain, grief and loss in a phenomenological perspective may offer new insights for patients as well as health care workers.

Meaning disruption – Creating meaning

Loss can be associated with expressions and feelings like anger, resentment, despair and disorganization, which indicate that the person experiences disrupted meaning and calls for ways of coping with life. The experience of incompetence, hopelessness and dejection are often present and may disturb everyday life and social ties.Citation13,Citation21 Loss caused by death may create feelings of helplessness and the experience of frustration. Anger often accompanies the loss situation. Loss caused by chronic pain is considered to be one of the most common and difficult emotions that chronic pain patients experience.Citation24 Here, the underlying source of their anger may be unclear and despair is often related to issues of loss. These losses may be related to identity, the ability to work, to engage in recreational or family activities. The anger can also be caused by feelings of despair that life has been unfair to them.Citation17,Citation24

Loneliness, suffering, depression and weakness may prevent meaningful reconstruction and lead to decreased ability to be involved in the world.Citation13 As a result, the grieving person often finds it difficult to experience life as meaningful in the complex and changed life situation. These loss experiences may influence engagement in valued social life. The present authors support RoyCitation2 and Hunt RaleighCitation18 who emphasize that there is an important challenge to help the grieving person to put in the background anger and despair, and instead focus on acceptance and hope which would create meaning. Meaningful reconstruction implies progress in coping with feelings and thoughts as part of the adaptation process.Citation19 This understanding is further deepened in , where the process is described as a continuous movement towards creating an enriched identity and seeing the world with new eyes.

An important task for health care workers assisting grieving people is to establish a positive attitude that is sustained through meaning construction. According to Lipps (referred to by Pahuus),Citation15 existence is to create an attitude to handle the situation which may be considered a meaningful reconstruction. As mentioned above, grieving and adaptation related to different loss situations involve taking a new life course. Relearning as meaning reconstruction is a cognitive skill as well as an important emotional and social skill which needs to be supported. The person in grief has to take an active part and find new meaning in several complex and difficult situations. In the grieving process valuable memories from the past must be preserved as an important first step in an adapted life situationCitation11,Citation21 According to the findings from Furnes,Citation13 memories about the past are described as giving important power to life and encouragement for the future. Similar findings are also related to loss caused by chronic pain.Citation21–Citation22 The extent to which living a meaningful life is possible seems to depend on many complex factors, including a person’s belief system and attitudes, early life experiences, illness, personal resources and the meaning of pain.Citation22

Bodily discomfort – Reintegrated body

We exist in the world as whole bodies.Citation12 Here this means that the grieving person carries the whole grief and pain situation bodily. This naturally leads to a commitment that the grieving person must be seen and met as a whole situated person. If we base our approach only on theories categorizing grief or stating grief as observable symptoms and reactions, we may exclude the integrated body. Such beliefs may lead health care workers to ignore grief as a unique experience. As a result, the grieving person may be convinced that his/her own experiences are unimportant and unreliable.

Specific bodily reactions may be described as “grief attack” followed by discomfort. Grief experiences caused by death may consist of bodily discomfort such as chest pain, nausea, headaches, limpness, and sleep disruption.Citation25 During chronic pain the unpleasant perceptual experience may become the center of mental awareness, and positive bodily perception is lost as physical pain may fill the consciousness.Citation1 Here, there is often a complex mixture of different types of pain such as physical pain, neuropathic pain, and psychogenic pain causing bodily discomfort.Citation26 Thus, grief may imply a stiff body and loss of movements indicating that the relation to the body is changed. Moreover, this may bring a “feeling of losing oneself ” and experiencing a sense of discontinuity with the world. To narrate is meaning reconstruction and a way to establish continuity in the world.Citation27 We believe that through narration and supervision the grieving person will express impressions related to grief and loss as part of the relearning and adaptation process. It represents a challenge to move towards a reintegrated body indicating that this can be met through alleviation and organization of thoughts and feelings.Citation13

Implications

Based on the present authors’ empirical based experiences and a theoretical integrated framework, grief work encompasses meeting the unique person in the specific life situation, capturing his or her expressions and experiences.Citation13,Citation21–Citation22 According to our understanding of the relationship between grief and loss caused by death or chronic pain, several perspectives are similar while others may differ, such as total loss caused by death of a close person and part loss caused by chronic nonmalignant pain. All experiences connected to loss may occur in various strengths and lengths independent of what is lost. Common features in the grieving process are expressed in our model (), based on relevant theory and the present authors’ research. The model could represent an increased understanding in the care of individuals who experience loss related to chronic pain as well as loss of someone close. Such, grief experiences as indicated in the figure, have processes in common which involve circular and vertical movements between relearning the world and adaptation. We emphasize that this integrated understanding of grief implies that health care workers must be aware of these continuous movements as illustrated, thus meeting the grieving person in their specific situation. Furthermore, the experiences (paired subthemes) in the model may be used as guidelines for systematic investigation, approaches, and follow-up in clinical practice.

Conclusion

An integrated theoretical framework on grief has been developed based on an open qualitative review of the literature. This framework to grief related to loss may represent an integrated understanding for interventions and research encompassing grief caused by death as well as health impairment caused by chronic pain. Grief and grief work as a distinctive experience entails that health care support and professional intervention must be aimed directly at each individual relation and position on the different continua. As such, grief experiences and grief work are walking backwards and living forwards. Clinical interventions have to be based on this concept.

The literature on grief seems to be incomplete with regard to some of the issues raised in this paper. There is a need for updated grief theory and interventions applied to the particular and very complex ongoing processes of grieving for those experiencing loss by death or chronic pain. In addition, there is a need to help patients develop adaptations to their unique situation. This means focusing on the movements between relearning the world and adaptation so that the self is reintegrated. We consider that this theoretical framework on grief related to loss should offer a relevant fundament for health care workers who are working with people experiencing grief caused by death and chronic pain. Part two of this paper will highlight suggestions for intervention programs based on the concepts and framework established here.

Disclosure

The authors report no confilicts of interest in this work.

References

- HarveyJHPerspectives on Loss, a SourcebookPhiladelphia, PATaylor and Francis1998

- RoyROld age, pain, and lossTop Geriatr Rehabil20011636676

- ParkesCMBereavement: Studies of Grief in Adult LifeLondon, UKPenguin1986

- LindgrenCLChronic sorrow in long-term illness across the life spanFitzgerald MillerJCoping with Chronic Illness, Overcoming PowerlessnessPhiladelphia, PADavis Company2000125145

- IASP subcommittee on taxonomyClassification of chronic pain. Descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain termsPain Suppl19863216221

- NortvedtFNortvedtPSmerte-fenomen og ForståelseOslo, NorwayGyldendal Akademisk2001

- Miller KahnACoping with fear and grievingLubkinIMChronic Illness, Impact and InterventionsBoston, MAJones and Bartlett Publishers1995241260

- FreudSMourning and melancholiaStracheyJThe Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund FreudLondon, UKHogarth1917/1957

- BowlbyJAttachment and LossNew York, NYBasic Books1980

- AttigTHow we grieve Relearning the worldOxford, UKOxford University Press1996

- AttigTRelearning the World: Making and Finding MeaningsNeimeyerRAMeaning Reconstruction and the Experience of LossWashington, DCAmerican Psychological Association20023353

- Merleau-PontyMKroppens fenomenologiOsloPax Forlag1994

- FurnesBÅ skrive sorgen – bearbeidelse av sorg. Prosessorientert skriving i møte med en fenomenologisk språkforståelse. En hermeneutisk fenomenologisk studie av skriving som sorgbearbeidelse hos etterlatte Doctoral thesis. University of Berger, Norway; 2008

- DelmarCThe Phenomenology of life phenomena – in a nursing contextNurs Philos2006423524616965305

- PahuusMHoldning og Spontanitet Pædagogik, menneskesyn og værdier Århus,DenmarkKvaN1997

- DworkinSFShermanJJRelying on objective and subjective measures of chronic pain: guidelines for use and interpretationTurkDCMelzackRHandbook of Pain Assessment2nd edNew York, NYGuilford Press2001619638

- WalkerJSofaerBHollowayIThe experience of chronic back pain: Accounts of loss in those seeing help from pain clinicsEur J Pain200610319920716490728

- RaleighHuntHope and hopelessnessRiceVHHandbook of Stress, Coping and Health Implications for nursing research, theory, and practiceLondon, UKSage Publications2000437459

- GatchelRJAdamsLPolatinPBKishinoNDSecondary loss and Pain-associated disability: theoretical overview and treatment implicationsJ Occup Rehabil20021229910912014230

- StroebeMSSchutHThe dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and descriptionDeath Studies199923319722410848151

- CharonRA narrative medicine for painCarrDBLoserJDMorrisDBNarrative, Pain, and SufferingSeattle, WAIASP Press20052944

- DysvikEStephensPConducting rehabilitation groups for people suffering from chronic painIntl J Nur Pract2010In press.

- BrattbergGVärckarklockor för människor i livets väntrumStockholm, NYVärkstaden1998

- KeefeFJBeauprePMGilKMRumbleMEAspnesAKGroup Therapy for Patients with Chronic PainTurkDCGathelRJPsychological Approaches to Pain ManagementNew York, NYThe Guilford press2002234255

- QvarnströmULindströmCUpplevelser inför döden En klinisk studie av anhørigas situasjon Delegationen för social forskning Rapport 6 Stockholm, SwedenLiber1982

- KoenigHGChronic pain, biomedical and spiritual approachesLondon, UKThe Haworth Pastoral Press2003

- NeimeyerRANarrative strategies in grief therapyJ Constructivist psych19991216585