Abstract

Background:

Premature discontinuation of treatment impacts outcomes of clinical practice. The traditional perception has been patient discontinuation is mainly driven by unwanted side effects. Systematic analysis of data from clinical trials across several disease states was performed to identify predictors of premature discontinuation during clinical interventions.

Methods:

A post hoc analysis was conducted on 22 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials for treatment of fibromyalgia, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Analyses were conducted on pooled data within each disease state.

Results:

Lack of early therapeutic response was a significant predictor of patient discontinuation in each disease state. Visit-wise changes in therapeutic response and severity of adverse events were also significant risk factors, with change in therapeutic response having a higher significance level in three disease states. Patients who discontinued due to adverse events had similar therapeutic responses as patients completing treatment.

Conclusion:

Contrary to the conventional belief that premature treatment discontinuation is primarily related to adverse events, our findings suggest lack of therapeutic response also plays a significant role in patient attrition. This research highlights the importance of systematic monitoring of therapeutic response in clinical practice as a measure to prevent patients’ discontinuation from pharmacological treatments.

Background

Treatment discontinuation from clinical interventions is a widespread phenomenon that occurs across disease states. It has been shown that patients who discontinue prematurely are likely to experience relapse of symptoms and other undesirable effects.Citation1,Citation2 The issue of patient attrition also impacts the analysis of clinical studies. For example, a reduction in sample size threatens the internal validity of a clinical study and limits generalizability of results.Citation3 Identification of factors that influence treatment discontinuation could lead to optimization of interventions and improved patient outcomes.

It is a common practice in clinical trials to record the reasons for discontinuation along with the percentage of patients who discontinue from the study. A review of published clinical trial results indicates that attrition rates among diabetic neuropathy clinical trials have ranged from 20% to 40%,Citation4–Citation8 18% to 26% among fibromyalgia clinical trials,Citation9–Citation13 23% to 38% among generalized anxiety disorder clinical trials,Citation14–Citation17 and 20% to 40%, among major depressive disorder clinical trials.Citation18 The two categories of treatment-related reasons for discontinuation are adverse events and lack of therapeutic response. The traditional perception has been that patient discontinuation is driven mainly by adverse events. Statistical analysis techniques can be utilized to further assess the risk factors of discontinuation.Citation3,Citation18,Citation23 Previously conducted research has found that poor therapeutic response and poor medication tolerability were significant predictors of patient discontinuation in schizophrenia clinical trials.Citation19 In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, patient attrition was associated with younger age, less education, and African American race.Citation18 Since randomized, controlled clinical trials provide information on therapeutic response and reasons for discontinuation; we conducted exploratory analyses of 22 clinical trials to systematically investigate the predictors of treatment discontinuation and, particularly, the relative impact of therapeutic response versus the impact of adverse events. This research was done in multiple disease states: major depressive disorder (MDD), diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (DPNP), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and fibromyalgia (FM).

Methods

Patient population

This was a post hoc, pooled analysis of clinical trials within the Eli Lilly and Company duloxetine database. The selection criteria for the clinical trials included in this research were 1) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2) disease states of major depressive disorder (MDD), diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (DPNP), fibromyalgia (FM), or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and 3) same primary efficacy measure for all studies within a disease state. Twenty-two studies met these criteria, with 3 studies of DPNP, 4 studies of FM, 4 studies of GAD, and 11 studies of MDD. All treatment groups were pooled together within each disease state for the purpose of this research.

Study designs

Analyses were conducted using the acute therapy phase of each clinical trial, during which treatment response and safety of treatment are evaluated for each patient. The DPNP studies included 1139 patients treated with duloxetine or placebo. The FM studies included 1411 patients treated with duloxetine or placebo. The GAD studies included 1908 patients treated with duloxetine, venlafaxine, or placebo. The MDD studies included 3270 patients treated with duloxetine, clomipramine, fluoxetine, paroxetine, escitalopram, or placebo. For each disease state, treatment duration for the studies varied: DPNP (12–13 weeks), FM (3–6 months), GAD (9–10 weeks), MDD (4–12 weeks). The FM studies also had extension phases of either 3 or 6 months.

Assessments

The primary objective of this analysis was to assess the pattern and reasons for discontinuation by pooling the data within the disease states of MDD, DPNP, GAD, and FM. Investigators in all studies were required to record the reason and date of discontinuation when patients left the trial before completing it. The reasons for discontinuation were as follows:

1) Lack of efficacy (LOE): The patient perception was that symptom improvement was not adequate. 2) Adverse event (AE): The patient experiences an unwanted side effect (with the event specified). 3) Subject decision: The patient decides to discontinue treatment for personal reasons, such as transportation, inconvenience and personal relocation. 4) Lost to follow-up: The patient did not come to a scheduled visit and could not be reached by phone or mail. 5) Physician decision: The physician decided that the patient should be discontinued due to reasons other than LOE or AE. 6) Protocol violation or violation of entry criteria: The requirements and procedures specified by the protocol were not followed or the patient was inappropriately enrolled into the clinical trial based on specific entry criteria. 7) Sponsor decision: The sponsor (Eli Lilly and Company) decided that a patient should be discontinued following consultation with the investigator treating the patient.

The primary efficacy measures recorded for each patient in these clinical trials were Likert scales, in which lower scores indicated lower presence of symptoms and higher scores indicated higher presence of symptoms. In the DPNP, FM, GAD, and MDD clinical trials, the primary efficacy measures were the weekly mean of the 24-hour average pain ratings, the 24-hour average pain item from the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale Total Score (HAMA), and the total score of the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17), respectively. The Likert scales used for these primary efficacy measures ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the most severe pain) for the DPNP and FM clinical trials, 0 (not present) to 56 (very severe) for the GAD clinical trials, and 0 (not depressed) to 68 (severely depressed) for the MDD clinical trials.

At each study visit, severity of adverse events was rated based on patients’ spontaneous reports using the scale where 1 indicates a mild event (noted change in patient’s condition that does not affect their usual activity), 2 indicates a moderately severe event (a mild disruption in patient’s usual activity), 3 indicates a severe event (a major disruption in patient’s usual activity), and 0 indicates no adverse events experienced during the visit. The maximum event severity rating of all adverse events for each patient at each visit was used in all statistical analyses.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were conducted separately for each of the four disease states, with treatment groups combined within each disease state. Summary statistics describing baseline demographics and illness severity are presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for discrete variables. A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was used for tests of significance.

To assess the predictive value of early therapeutic response, lack of early therapeutic response, and adverse reaction, a stepwise logistic regression analysis was implemented to determine factors associated with patient discontinuation, using baseline demographic factors as well as percent change in therapeutic response from baseline visit (PCTHR) and maximum event severity rating (MXSEV) at the first post-baseline visit. Entry and exit of covariates was determined using an alpha level of 0.05. Standardized versions of PCTHR and MXSEV were formed to produce a common scale and facilitate clear interpretations; standardized therapeutic response (STR) and standardized adverse reaction (SAR).

In order to evaluate the continuous effect of therapeutic response and adverse reactions in treatment discontinuation throughout the therapy phase, a stepwise Cox regression model using demographic factors and visit-wise PCTHR and MXSEV as time-varying covariates was used. As in the logistic regression analysis, entry and exit of covariates was determined using an alpha level of 0.05 and standardized versions of PCTHR and MXSEV (STR and SAR respectively) were formed for clearer interpretations.

For statistical models such as the logistic regression and Cox regression models, the value of the maximum likelihood function measures the agreement between the proposed model and the observed data using the particular set of predictors included in the model. Let L(full) denote the maximized likelihood value for the full predictive model, and L(reduced) denote the maximized likelihood for the reduced model. The full model contains the predictors STR, SAR, and any additional significant predictors, while the reduced model contains the same predictors as the full model, but without either STR or SAR. To determine whether STR or SAR contributes more to the final model predicting patient discontinuation, two likelihood ratio tests were conducted. These two tests involved computing the difference of (−2*log(L(reduced))) and (−2*log(L(full))) which is distributed as a chi-square distribution with one degree of freedom. A large difference indicates that the additional predictor of either STR or SAR in the final model compared to the model that excluded one of those predictors improves the adequacy of the final model.Citation21 The test that produces the largest difference determined which predictor (STR or SAR) contributed more to the final predictive model.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the differences in therapeutic response between patients who discontinue before the end of the therapy phase and patients who completed the acute therapy. A similar analysis was also conducted where patients who discontinued due to various reasons as well as completers were compared. Results of the ANOVA analysis were presented using least-square means plots of treatment efficacy for the different groups of patients at time points common in all studies within each disease state.

Results

summarizes the sample of patients at baseline across the 4 disease states with treatment groups combined. A majority of patients were female (66%) and Caucasian (83%). The patient mean age was 46.05 ± 13.80. The mean baseline BPI average pain score for FM patients was 6.44 ± 1.57. The baseline weekly mean of the 24-hour average pain rating for DPNP patients was 5.83 ± 1.47. The mean baseline HAMA total score for GAD patients was 25.55 ± 7.22. The mean baseline HAMD-17 total score for MDD patients was 19.68 ± 5.00.

Table 1 Baseline patient characteristics

Reasons for discontinuation

The reasons for discontinuation are summarized in . About one-third of the patients discontinued from these 22 studies. The studies for FM had the highest overall discontinuation rate (42%) and the studies for DPNP had the lowest overall discontinuation rate (22%). Discontinuations due to lack of efficacy were highest in MDD studies (27%) and lowest in DPNP studies (7.5%). With the exception of MDD studies, each other disease state had a higher rate of discontinuations due to adverse reactions than lack of therapeutic response.

Table 2 Reasons for discontinuation by disease state

Baseline predictors of discontinuation

Certain demographic factors were associated with discontinuation. African American patients were 1.6 times more likely to discontinue than Caucasian patients in MDD clinical trials. Age was also associated with patient discontinuation in MDD and GAD clinical trials. For each additional 10 years of age respectively the odds of discontinuation decreased by a factor of 0.9 and 0.98. Patients treated in European countries were 0.44 times more likely to discontinue than patients treated in the United States in DPNP clinical trials.

Early predictors of discontinuation

In the FM, MDD, and GAD disease states, standardized adverse reaction and standardized therapeutic response at first post-baseline visit were significant predictors of study completion. In the DPNP disease state, SAR was a significant predictor of study completion but not STR (). For every increase of one standard deviation in STR (SAR) which indicates worse outcomes, the odds of discontinuing from the study were increased by 20% (14%), 19% (23%), 22% (25%) for patients in the MDD, FM, and GAD disease states, respectively. For patients in the DPNP disease state, the odds of discontinuing from the study were increased by 58% for every increase of one standard deviation in SAR, but STR was not identified as a significant predictor in the stepwise logistic regression procedure. In the FM and GAD disease states, SAR was identified ahead of STR in the stepwise logistic regression procedures, while the opposite was true for MDD.

Table 4 Logistic regression results on impact of early therapeutic response and adverse reactions

contains the results of the likelihood ratio tests comparing the full models predicting the probability of discontinuation in each disease state with models missing either standardized therapeutic response or standardized adverse reaction. In the FM, MDD, and GAD disease states, the inclusion of STR to the full logistic regression model produced a larger difference than the inclusion of SAR, indicating that STR contributed more to the final model. Even though the stepwise logistic regression procedure did not identify STR as a significant predictor of study completion in the DPNP disease state, the likelihood ratio test procedure demonstrated that the inclusion of STR contributed more to the final predictive model than the inclusion of SAR.

Table 5 Logistic regression likelihood ratio tests results

Continuous predictors of discontinuation

In all four disease states, symptom improvement from the baseline visit to each visit after baseline as measured by STR and SAR in each post-baseline visit were significantly predictive of the risk of discontinuation (). The increased risk in discontinuation for patients in the FM, MDD, and DPNP disease states who experienced an increase (worsening) of one standard deviation in STR was approximately 45% over patients with no increase (worsening) in STR. For each of these three disease states, STR was identified ahead of SAR during the stepwise regression procedure. Patients in DPNP studies experienced a 25% increased risk in discontinuation for every increase of one standard deviation in STR over patients with no increase in STR. In the DPNP disease state, SAR was identified ahead of STR during the stepwise regression procedure. The increased risk of discontinuation for patients who experienced an increase of one standard deviation in SAR ranged from 34% to 47% in FM, MDD, and GAD studies over patients with no increase in SAR, and 87% for DPNP study patients over patients with no increase in SAR.

Table 6 Cox regression results on continuous effect of treatment response and adverse reactions

contains the results of the likelihood ratio tests comparing the full models predicting risk of discontinuation in each disease state with models missing either standardized therapeutic response or standardized adverse reaction. In the FM, MDD, and GAD disease states, the inclusion STR to the final Cox regression model produced a larger difference statistic than the inclusion of SAR, indicating that STR contributed more to the final model. In the DPNP disease state, the opposite was the case. The likelihood ratio test procedure demonstrated that that the inclusion of SAR contributed more to the final Cox regression model than the inclusion of STR.

Table 7 Cox regression likelihood ratio tests results

Completers versus patients who discontinued

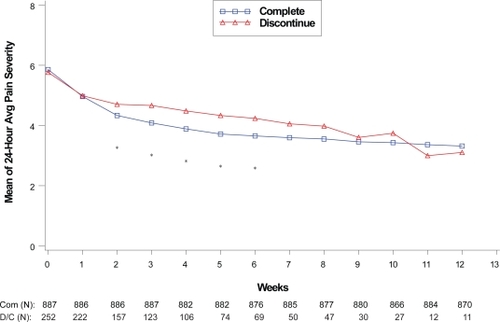

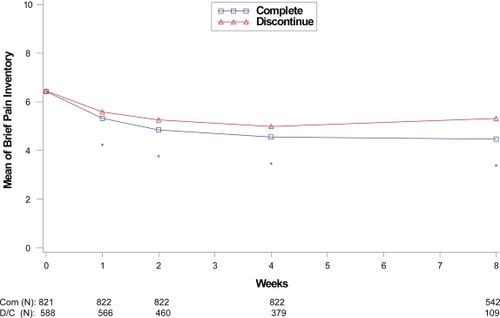

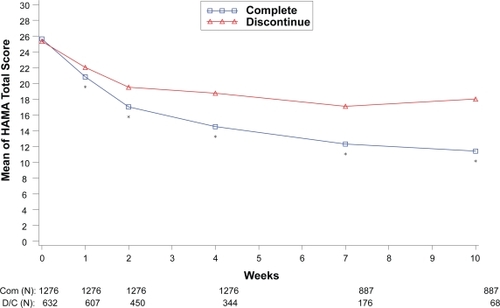

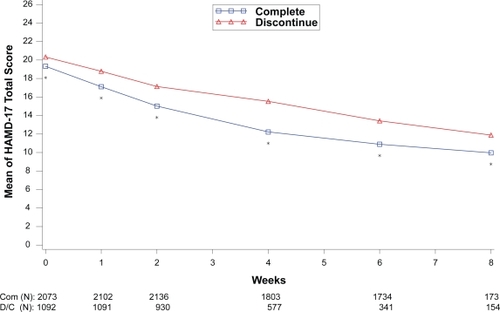

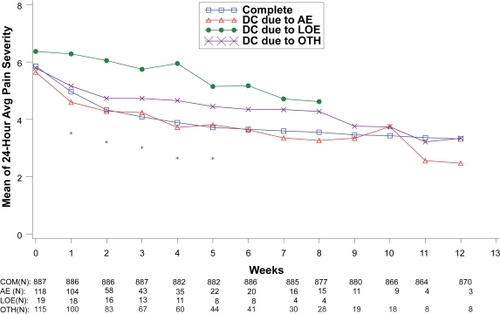

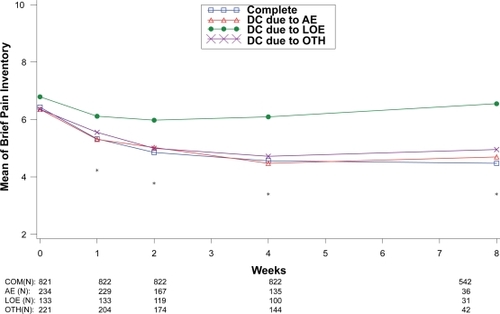

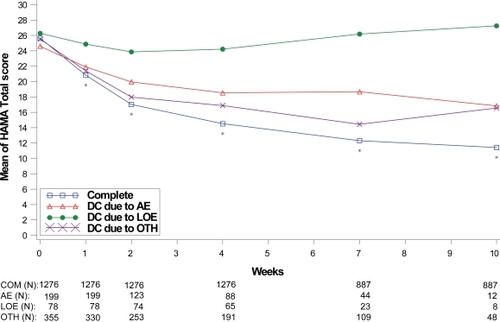

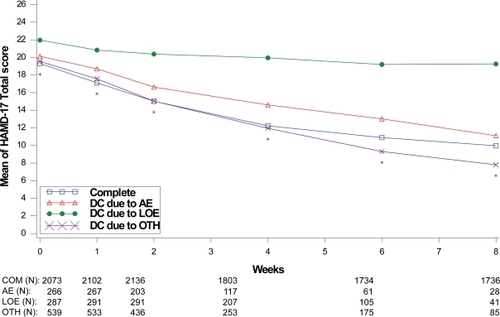

Within each disease state, therapeutic response values at each assessment were compared between the patients who completed the therapy phase and those who discontinued from the therapy phase as shown in to . For all disease states except MDD, there was no significant difference in baseline values of primary outcome measure between the patients who completed and those who discontinued from the study. However, at each assessment after the baseline visit for the disease states MDD, GAD, and FM, patients who completed the study had significantly greater therapeutic response than those who discontinued before the end of the therapy phase. Patients who completed the therapy phase in DPNP studies had significantly greater therapeutic response in weeks 2 through 6 than patients who discontinued treatment.

Figure 1 Visit-wise 24-hour average pain severity scores between patients who completed therapy phase and those who discontinued early in DPNP studies.

Values are means across all treatments and studies.

*p value < 0.05 between group differences. Avg, average; COM, completers; D/C, discontinue.

(N) denotes number of patients at specific time point.

Figure 2 Visit-wise brief pain inventory scores between patients who completed therapy phase and those who discontinued early in fibromyalgia studies.

Values are means across all treatments and studies.

*p value < 0.05 between group differences. COM, completers; D/C, discontinue.

(N) denotes number of patients at specific time point.

Figure 3 Visit-wise HAMA Total scores between patients who completed therapy phase and those who discontinued early in GAD studies.

Values are means across all treatments and studies.

*p value < 0.05 between group differences. COM, completers; D/C, discontinue.

(N) denotes number of patients at specific time point.

Figure 4 Visit-wise HAMD-17 Total scores between patients who completed therapy phase and those who discontinued early in MDD studies.

Values are means across all treatments and studies

*p value < 0.05 between group differences. COM, completers; D/C, discontinue.

(N) denotes number of patients at specific time point.

Treatment response values at each assessment were also compared between the patients who completed the therapy phase and those who discontinued treatment due to lack of efficacy, adverse events, and “other” reasons as shown in to . For all disease states except MDD, there was no significant between-group difference in baseline values of the primary efficacy outcome measure. Similar to the comparisons of therapy phase completers and those who discontinued from treatment, patients treated for MDD, GAD, and FM had significant between-group differences at each week past the baseline visit. Patients treated for the DPNP disease state had significant between-group differences in weeks 1 through 5. While patients who discontinued due to lack of efficacy had the lowest therapeutic response, patients who discontinued due to adverse events showed similar therapeutic response as therapy completers in the first 5 weeks of treatment in all four disease states.

Figure 5 Visit-wise 24-hour average pain severity scores between patients who completed therapy phase and those who discontinued early for various reasons in DPNP studies.

Values are means across all treatments and studies.

*p value < 0.05 between group differences. Avg, average; AE, adverse events; COM, completers; DC, discontinue; LOE, lack of efficacy; OTH, other reasons.

(N) denotes number of patients at specific time point.

Figure 6 Visit-wise brief pain inventory scores between patients who completed therapy phase and those who discontinued early for various reasons in fibromyalgia studies.

Values are means across all treatments and studies.

*p-value < 0.05 between group differences. AE, adverse events; COM, completers; DC, discontinue; LOE: lack of efficacy; OTH, other reasons.

(N) denotes number of patients at specific time point.

Figure 7 Visit-wise HAMA total scores between patients who completed therapy phase and those who discontinued early for various reasons in GAD studies.

Values are means across all treatments and studies.

*p value < 0.05 between group differences. AE, adverse events; COM, completers; DC, discontinue; LOE, lack of efficacy; OTH, other reasons.

(N) denotes number of patients at specific time point.

Figure 8 Visit-wise HAMD-17 total scores between patients who completed therapy phase and those who discontinued early for various reasons in MDD studies.

Values are means across all treatments and studies.

*p value < 0.05 between group differences. AE, adverse events; COM, completers; DC, discontinue; LOE, lack of efficacy; OTH, other reasons.

(N) denotes number of patients at specific time point.

Discussion

The aim of our analyses was to investigate therapeutic response and adverse reactions as predictors of treatment discontinuation in multiple disease states. Early therapeutic response as measured by standardized percent change in the primary efficacy outcome measure and severity of adverse event as measured by standardized scale at first post-baseline visit were both significant predictors of premature treatment discontinuation in MDD, GAD, and FM disease states. In diabetic neuropathy, early therapeutic response was not a statistically significant predictor using the stepwise logistic regression procedure, but it significantly improved the overall adequacy of the model according to the likelihood ratio test procedure. Continuous therapeutic response at each visit throughout the studies provided a greater contribution to the prediction models than adverse reactions in the MDD, GAD, and FM disease states, while the opposite was true for diabetic neuropathy trials. These findings do not depend on the treatment group as the same results were seen within the placebo treated patients as well as within the duloxetine treated patients. Also study duration was not a significant predictor of treatment discontinuation in three of the four disease states (see for average discontinuation rates by duration in each disease state). These findings highlight the need for increased awareness of patients’ response to treatment and adverse reactions in all stages of treatment. If a patient demonstrates inadequate treatment response or experiences severe adverse reactions to treatment, clinicians could alter treatment options, provide educational information, or utilize other interventions to help the patient achieve improved treatment response.

Table 3 Average discontinuation percentages by disease state and duration

This research demonstrates that, contrary to the common belief that the onset of adverse events is the primary cause of discontinuation, therapeutic response plays just as important a role in predicting discontinuation. Results presented here indicate that early therapeutic response contributed more to the adequacy of the model predicting discontinuation than early adverse reactions in all four disease states. The fact that this occurred in all four disease states is consistent with findings that discontinuation profiles are similar among antidepressants of the same class in MDD, GAD, and social anxiety disorder (SAD).Citation22 Therapeutic response measured at each visit contributed more to the adequacy of the model predicting the risk of discontinuation than adverse reaction severity measured at each visit in all disease states except DPNP. For patients in DPNP clinical trials, adverse event severity measured at each visit was the primary predictor of the risk of discontinuation, indicating that these medically vulnerable patients could be either less tolerant or experiencing more severe adverse events. Patients with diabetes may have been exposed to life-long therapies due to chronicity of their disease state and may have been less sensitive to therapeutic response within a relatively short period of time and more sensitive to adverse events.

Patients who discontinued prematurely from the treatment showed significantly less improvement at most time points past the baseline visit. In three of the four disease states (DPNP, FM, MDD), patients who discontinued due to adverse events demonstrated symptom improvement comparable to patients completing the studies. This is not too surprising as similar results were found in analyses of schizophrenia clinical trials as well.Citation19 While adverse events have been accepted as unavoidable consequences of effective treatment, these findings provide quantitative evidence that adverse events could be significant barriers to effective treatment. It is thus critical for clinicians to provide guidance and education to patients about the importance of adherence to medication regimens especially when the adverse events are not excessively burdensome or the adverse events may be transient. GAD trials did not demonstrate a similar pattern of improvement in patients who discontinued due to adverse events, indicating the possibility that lack of efficacy could have been a contributing factor to their discontinuation from treatment, even though adverse events were the cited reason for it.

Previous research has identified a diverse set of predictors of attrition, such as sociodemographic factors, physical and mental factors, and study characteristics.Citation23,Citation24 Our research has also identified a set of demographic factors predicting patient discontinuation across the four disease states, such as race and age in MDD and GAD studies and country in DPNP studies. Age has been found to be negatively associated with discontinuation in previous research among patients with depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, or social anxiety disorder taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).Citation20 While the primary predictors of treatment efficacy and adverse event severity were mostly consistent among the disease states, the patient populations are different enough to warrant separate analyses for each disease state.

One limitation of the present analysis is the lack of active treatment arms besides duloxetine in the majority of clinical trials used in this analysis. Only placebo-controlled trials with no other active treatment arms besides duloxetine were included in the DPNP and FM disease states, and only two studies in the GAD disease state included another active treatment arm. The importance of therapeutic response and adverse reaction as predictors of discontinuation was consistent when interaction with treatment assignment was implemented in the prediction models. Further studies are needed to confirm that the greater impact of therapeutic response over adverse reaction is consistent across placebo and active treatment arms. Also, the reason of discontinuation recorded for patients may not capture the primary reason for discontinuation for some patients, although this is typically not the norm in clinical trials. For example, an investigator may have recorded the reason for discontinuation as “subject decision,” but the patient’s decision to discontinue could have been driven by a perceived lack of treatment efficacy or medication intolerability. One possible solution is to collect additional data such as the likelihood of a patient attending the next treatment session.Citation7 In the FM and MDD trials, the majority of patients were treated within North America (89% and 85% respectively), which may not be optimal in determining differences in discontinuation profiles between patients treated in North America and outside of it. Lastly, all but one of the clinical studies satisfying our selection criteria were phase III clinical studies, which could limit the generalizability of our results to patients in real-world settings.

In conclusion, the findings of our research highlight the need for increased awareness and monitoring of patients’ medication intolerability and lack of therapeutic response in all phases of treatment, especially early on. While discontinuation rates due to adverse events and lack of therapeutic response were different for each of the four disease states, early therapeutic response and adverse event severity as well as visit-wise therapeutic response and adverse event severity both significantly predicted the risk of discontinuation in each disease state. This indicates that a high level vigilance is of great importance in every clinical practice relying on continuous pharmacotherapy. In therapeutic areas such as mood and pain studied in this research where patients can subjectively perceive therapeutic response, it is more likely that patients will evaluate the effectiveness of the therapy by weighing the cost against the benefit and subsequently make their choices on adherence to the medication regimen. Guidance or interventions from clinicians could help patients to become more encouraged and engaged in their treatment with the goal of a maximized patient outcome.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Appreciation is expressed to Lingling Xie, Terry Locklear, and Naresh Golpalkrishna for technical assistance and to Keyra Martinez, Eva Delgado, and Patricia Kent for editorial assistance with the manuscript.

Disclosures

H-LS and VS are employees of Eli Lilly and Company.

References

- ConnorKMTreatment of generalized anxiety disorder: current options and future developments. In: Culpepper L, chair. Effective recognition and treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in primary care [ACADEMIC HIGHLIGHTS]Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry20046354115486599

- SheltonRSteps following attainment of remission: discontinuation of antidepressant therapyPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry2001316817415014601

- LeonACMallinckrodtCHChuang-SteinCArchibaldDGArcherGEChartierKAttrition in randomized controlled clinical trials: methodological issues in psychopharmacologyBiological Psychiatry2007591001100516503329

- GoldsteinDJLuYDetkeMJLeeTCIyengarSDuloxetine vs placebo in patients with diabetic neuropathyPain20051161–210911815927394

- RichterRWPortenoyRSharmaULamoreauxLBockbraderHKnappLERelief of painful diabetic neuropathy with pregabalin: a randomized, placebo-controlled trialJ Pain20056425326015820913

- BackonjaMGlanzmanRLGabapentin dosing for neuropathic pain: evidence from randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trialsClin Ther20032518110412637113

- VinikATuchmanMSafirsteinBLamotrigine for treatment of pain associated with diabetic neuropathy: results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studiesPain20071281216917917254713

- DograSBeydounSMazzolaJHopwoodMWanYOxcarbazepine in painful diabetic neuropathy: a randomized, placebo-controlled studyEur J Pain20059554355416139183

- PatkarAAMasandPSKrulewiczSA randomized, controlled, trial of controlled release paroxetine in fibromyalgiaAm J Med2007120544845417466657

- ArnoldLMGoldenbergDLStanfordSBGabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-center trialArthritis Rheum20075641336134417393438

- VittonOGendreauMGendreauJKranzlerJRaoSGA double-blind placebo-controlled trial of milnacipran in the treatment of fibromyalgiaHum Psychopharmacol200419Suppl 1S27S3515378666

- CroffordLJRowbothamMCMeasePJPregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialArthritis Rheum20055241264127315818684

- ArnoldLMCroffordLJMartinSAYoungJPSharmaUThe effect of anxiety and depression on improvements in pain in a randomized, controlled trial of pregabalin for treatment of fibromyalgiaPain Med20078863363818028041

- RynnMRussellJEricksonJEfficacy and safety of duloxetine in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a flexible-dose, progressive-titration, placebo-controlled trialDepress Anxiety200825318218917311303

- DavidsonJRBoseAKorotzerAZhengHEscitalopram in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose studyDepress Anxiety200419423424015274172

- RickelsDZaninelliRMcCaffertyJBellewKIyengarMSheehanDParoxetine treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled studyAm J Psychiatry2003160474975612668365

- PandeACCrockattJGFeltnerDEPregabalin in generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled trialAm J Psychiatry2003160353354012611835

- WardenDTrivediMHWisniewskiSRPredictors of attrition during initial (citalopram) treatment of depression: a STAR*D reportAm J Psychiatry20071641189119717671281

- Liu-SeifertHAdamsDHKinonBJDiscontinuation of treatment of schizophrenic patients is driven by poor symptom response: A pooled post hoc analysis of four atypical antipsychotic drugsBMC Med2005232116375765

- MullinsCDShayaFTMengFWangJHarrisonDPersistence, switching, and discontinuation rates among patients receiving sertraline, paroxetine, and citalopramPharmacotherapy20052566066715899727

- CollettDModelling Survival Data in Medical Research2nd edLondonChapman and Hall/CRC2003

- BaldwinDSMontgomerySANilRLaderMDiscontinuation Symptoms in depression and anxiety disordersInt J Neuropsychopharmacol200710738416359583

- MoserDKDracupKDoeringLVFactors differentiating dropouts from completers in a longitudinal, multicenter clinical trialNurs Res200049210911610768588

- KhanASchwartzKReddingNKoltsRLBrownWAPsychiatric diagnosis and clinical trial completion rates: Analysis of the FDA SBA reportsNeuropsychopharmacology2007322422243017314915