Abstract

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, have come to play an important role in the pharmacologic management of arthritis and pain. Clinical trials have established the efficacy of etoricoxib in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, acute gouty arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, low back pain, acute postoperative pain, and primary dysmenorrhea. Comparative studies indicate at least similar efficacy with etoricoxib versus traditional NSAIDs. Etoricoxib was generally well tolerated in these studies with no new safety findings during long-term administration. The gastrointestinal, renovascular, and cardiovascular tolerability profiles of etoricoxib have been evaluated in large patient datasets, and further insight into the cardiovascular tolerability of etoricoxib and diclofenac will be gained from a large ongoing cardiovascular outcomes program (MEDAL). The available data suggest that etoricoxib is an efficacious alternative in the management of arthritis and pain, with the potential advantages of convenient once-daily administration and superior gastrointestinal tolerability compared with traditional NSAIDs.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal conditions are often progressive and associated with considerable pain and disability (CitationWHO 2005). These conditions place a huge burden on society in terms of lost productivity and the cost of treatment (CitationWHO 2005). Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), osteoarthritis (OA), and spinal disorders (including chronic low back pain [LBP]) are among those musculoskeletal conditions with the greatest impact on society (CitationWHO 2005). Approximately 14% of all primary care visits are for musculoskeletal pain or dysfunction (CitationACRCCG 1996). Symptomatic OA affects approximately 10% of men and 18% of women over 60 years of age (CitationWHO 2005), while RA affects between 0.3% and 1% of adults worldwide (CitationWHO 2005). Approximately 2.0% of all disability-adjusted life years are lost due to musculoskeletal diseases, including 1.0% due to OA, and 0.3% due to RA (CitationWHO 2004).

Current approaches to the management of these conditions are many and varied, but pharmacologic intervention is usually required at some stage for relief of acute or chronic pain and inflammation. In patients with RA, treatment with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is usually required as part of initial drug therapy, alongside disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and/or glucocorticoids (CitationACRRAG 2002). Pharmacologic intervention in patients with OA, as an adjunct to nonpharmacologic strategies, may include the use of acetaminophen or NSAID therapy (ACRSOG 2002). Analgesic drugs, including NSAIDs, also play a regular role in the management of other chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes such as low back pain and ankylosing spondylitis, and in other painful conditions including postsurgical dental pain and headache (CitationArgoff 2002).

Selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, a subclass of NSAIDs, continue to have a place in the management of RA and OA (CitationACRRAG 2002; ACRSOG 2002; CitationCush et al 2006). NSAIDs inhibit the COX-mediated synthesis of prostaglandins, which are important intermediaries in the development of inflammation and pain. Traditional NSAIDs inhibit both constitutive COX-1 and inducible COX-2, two processes which are believed to be responsible for the adverse effects (primarily gastrointestinal toxicity) and clinical benefits of treatment, respectively (CitationWarner and Mitchell 2004). Dyspeptic upper gastrointestinal symptoms with chronic use of traditional NSAIDs often lead to discontinuation by the patient with consequent inadequate pain control, switching from one NSAID to another, or the addition of a gastroprotective agent to prevent or treat upper gastrointestinal symptoms or clinical events (CitationWatson et al 2004). Major gastrointestinal complications, such as perforation, ulcers, and bleeding may require visits to the emergency department, hospitalization, and endoscopic or barium tests. In addition to discomfort and inconvenience for the patient, the costs of dealing with these adverse events are substantial (CitationMoore et al 2004).

In contrast, selective COX-2 inhibitors have greater affinity for COX-2 than COX-1. Clinical evidence has shown that selective COX-2 inhibitors have comparable efficacy with traditional NSAIDs in the treatment of arthritis and pain, but offer the major advantage of reduced gastrointestinal toxicity (CitationWarner and Mitchell 2004), thus providing physicians with an important therapeutic alternative. Recently, reports from two long-term studies in patients with a history of colorectal adenomas have detailed an increased risk of cardiovascular events associated with the COX-2 inhibitors celecoxib and rofecoxib compared with placebo (CitationBresalier et al 2005; CitationSolomon et al 2005), leading to questions about the cardiovascular safety of these agents (CitationDrazen 2005; CitationPsaty and Furberg 2005), and highlighting the importance of careful patient selection based on the benefits and risks of treatment.

This article will review available data regarding the efficacy and tolerability of etoricoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor that has been evaluated in arthritis and pain.

Pharmacology

In vitro, etoricoxib exhibits a greater selectivity for COX-2 over COX-1 compared with the COX-2 inhibitors rofecoxib, valdecoxib, and celecoxib (CitationRiendeau et al 2001; CitationTacconelli et al 2002). Etoricoxib binds competitively to COX-2 with 1:1 stoichiometry in a reversible, noncovalent manner (CitationRiendeau et al 2001). In human whole blood assays, etoricoxib inhibited COX-2 with an IC50 of 1.1 ± 0.1 μM, compared with an IC50 of 116 ± 8 μM for COX-1, representing 106-fold selectivity for COX-2 over COX-1 (CitationRiendeau et al 2001). No inhibitory effect was observed against a wide range of other receptors and enzymes evaluated. Selective COX-2 inhibition was also observed in ex vivo blood samples from healthy human volunteers who received etoricoxib at various therapeutic and supratherapeutic doses (CitationDallob et al 2003). Etoricoxib produced markedly less interference with the cardioprotective COX-1-mediated antiplatelet activity of low-dose aspirin in vitro than other NSAIDs including (in ascending order of aspirin antagonism) rofecoxib, valdecoxib, celecoxib, and ibuprofen, reflecting the lower affinity of etoricoxib for COX-1 (CitationOuellet et al 2001). These findings are consistent with results from clinical studies in which ibuprofen, but not rofecoxib (CitationCatella-Lawson et al 2001) or etoricoxib (CitationWagner et al 2001), antagonized aspirin antiplatelet activity. Etoricoxib showed potent, dose-dependent efficacy similar to other NSAIDs in animal models of acute inflammation, hyperalgesia, pyresis, and chronic adjuvant-induced arthritis (CitationRiendeau et al 2001). Preclinical and clinical data were consistent with the gastrointestinal tolerability of selective COX-2 inhibition; no effects on gastrointestinal integrity were observed in animal models as measured by urinary or fecal excretion of 51creatinineethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (51Cr-EDTA), an inert compound that is not taken up by extravascular tissue after its absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, but is completely excreted by the kidney (CitationRiendeau et al 2001). Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis in the gastric mucosa was not significantly different from that of placebo in human volunteers (CitationDallob et al 2003).

In healthy volunteers, oral etoricoxib is rapidly and completely absorbed. It reaches Cmax after approximately 1 hour and has up to 100% absolute bioavailability (CitationAgrawal, Porras, et al 2003; CitationRodrigues et al 2003). Absorption is slowed, but not diminished, following a high-fat meal meaning that etoricoxib can be administered without dietary consideration (CitationAgrawal, Porras, et al 2003). Etoricoxib shows linear pharmacokinetics through doses at least 2-fold higher than the maximum anticipated clinical dose (120 mg) (CitationAgrawal, Porras, et al 2003). Steady state conditions are reached after 7 days of daily administration, with an accumulation half-life of approximately 22 hours and an apparent terminal half-life of approximately 25 hours (CitationAgrawal, Porras, et al 2003), supporting once-daily dosing.

Etoricoxib is extensively metabolized and excreted mostly in the urine, with less than 1% of the oral dose recovered intact from urine (CitationRodrigues et al 2003). It is metabolized primarily by 6′-methyl hydroxylation in human liver microsomes, a process catalyzed in large part (∼60%) by members of the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A subfamily with lesser contributions by multiple other CYP isoenzymes including CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and possibly CYP2C19 (CitationKassahun et al 2001). Etoricoxib is a weak inhibitor of CYP3A and other CYP isoenzymes in vitro (IC50 > 100 μM) (CitationKassahun et al 2001), and has a minimal inhibitory effect on CYP3A activity in healthy volunteers (CitationAgrawal et al 2004b). Coadministration of CYP3A inhibitors in healthy volunteers increased the etoricoxib area under the curve, but this effect was not considered to be clinically relevant (CitationAgrawal et al 2004b). In contrast, agents that strongly induce CYP3A may reduce etoricoxib concentrations below therapeutic levels (CitationAgrawal et al 2004b). Patients with mild to moderate hepatic insufficiency exhibit reduced clearance of etoricoxib. The etoricoxib dose should not exceed 60 mg once daily in patients with mild hepatic insufficiency (Child-Pugh score 5 to 6), and 60 mg every other day in patients with moderate hepatic insufficiency (Child-Pugh score 7 to 9). No data are available for patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh score ≥ 10), and etoricoxib is not recommended for use in this patient population (CitationAgrawal, Rose, et al 2003). Renal insufficiency has little impact on etoricoxib pharmacokinetics and no dosage adjustment is required (CitationAgrawal et al 2004a). However, etoricoxib, similar to other selective and traditional NSAIDs, appears to have dose-related renovascular effects (see renovascular tolerability section) (CitationCurtis et al 2004), and use of etoricoxib in patients with a creatinine clearance < 30 ml/min is contraindicated (CitationEMEA 2005a).

Clinical studies

Clinical studies have established the efficacy and tolerability of etoricoxib in arthritis and pain, and the drug is available in over 50 countries worldwide. Etoricoxib is approved in Europe for the symptomatic relief of OA, RA, and the pain and signs of inflammation associated with acute gouty arthritis (CitationEMEA 2005a), whereas the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has requested additional efficacy and safety data prior to approval of etoricoxib. Some countries in Latin America and Asia have additional indications including LBP, ankylosing spondylitis, and primary dysmenorrhea

Efficacy

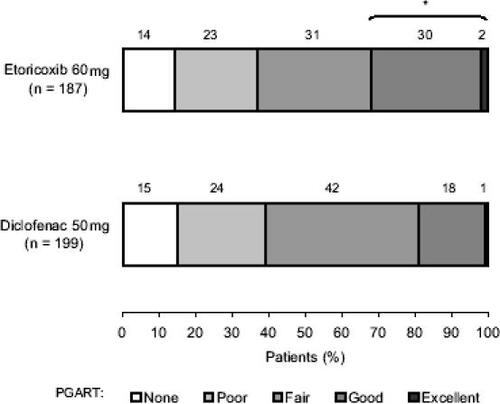

Etoricoxib in the treatment of osteoarthritis Clinical studies have shown that etoricoxib is more effective than placebo, and of similar efficacy to traditional NSAIDs, in the treatment of OA. A dose-ranging study in 617 patients with knee OA established that etoricoxib 5 mg to 90 mg every day (QD) was more effective than placebo after 6 weeks as measured by the Western Ontario and McMaster’s University OA Index (WOMAC) pain subscale and patient and investigator global assessments (p < 0.05 each comparison), with maximal efficacy at a dosage of 60 mg QD (CitationGottesdiener et al 2002). The efficacy of etoricoxib 60 mg QD was comparable with that of diclofenac 50 mg three times daily (TID) in long-term extensions of this study for up to 52 weeks (CitationCurtis et al 2005) and up to a total of 190 weeks (CitationFisher et al 2003) Etoricoxib 60 mg QD and diclofenac 50 mg TID also showed comparable efficacy in a 6-week, randomized study of 516 patients with hip or knee OA assessed using the WOMAC pain subscale (CitationZacher et al 2003), irrespective of baseline disease severity (CitationFrizziero et al 2004). Interestingly, in this study etoricoxib had a more rapid effect with significantly more patients reporting a good or excellent response within 4 hours of the first dose compared with diclofenac () (CitationZacher et al 2003).

Figure 1 Osteoarthritis PGART 4 hours ± 15 minutes after the first dose of etoricoxib versus diclofenac. This randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of etoricoxib 60 mg QD versus diclofenac 50 mg TID over 6 weeks in 516 patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. The treatments were of comparable efficacy on all primary and secondary efficacy endpoints (data not shown), except for the analysis of early efficacy illustrated here in which a greater percentage of patients reported good or excellent PGART responses within 4 hours of receiving their first dose of etoricoxib compared with diclofenac. Copyright © 2003. Reproduced with permission from CitationZacher J, Feldman D, Gerli R, et al. 2003. A comparison of the therapeutic efficacy and tolerability of etoricoxib and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis. Curr Med Res Opin, 19:725–36.

* p = 0.007 for good or excellent PGART with etoricoxib versus diclofenac.

The Etoricoxib versus Diclofenac sodium Gastrointestinal tolerability and Effectiveness (EDGE) study which primarily evaluated gastrointestinal tolerability in 7111 patients with hip, knee, hand, or spine OA, showed sustained and comparable improvements in Patient’s Global Assessment of Disease Status (PGADS) with etoricoxib 90 mg QD or diclofenac 50 mg TID at 12 months (CitationBaraf et al 2004). Two randomized, double-blind, 12-week studies in a total of 997 patients with hip or knee OA showed that etoricoxib 60 mg QD and naproxen 500 mg TID were of comparable efficacy, and superior to placebo, as measured by WOMAC pain and physical function subscales and PGADS (CitationFisher et al 2001; CitationLeung et al 2002). In addition, patients receiving etoricoxib or diclofenac also experienced treatment-related significant improvements in social and emotional quality of life and vitality (CitationHunsche et al 2002). Early improvements in patient condition were observed 2 days after initiating etoricoxib treatment (CitationLeung et al 2002) and then maintained through up to 138 weeks on study extensions (CitationReginster et al 2004).

The recommended etoricoxib dosage for OA is 60 mg QD (CitationEMEA 2005a); however, etoricoxib also appears to offer effective pain relief at lower doses consistent with the initial dose-ranging findings (CitationGottesdiener, 2002). A recent randomized trial in 528 patients with hip or knee OA demonstrated that the efficacy of etoricoxib 30 mg QD was comparable with that of ibuprofen 800 mg TID over 12 weeks on the WOMAC pain and physical functioning subscales and PGADS (p < 0.001 versus placebo for all comparisons) (CitationWiesenhutter et al 2005).

Etoricoxib in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

The efficacy of etoricoxib is similar to, or greater than, that of conventional NSAIDs in patients with RA. In a randomized study evaluating etoricoxib doses of 10, 60, 90, and 120 mg QD in 581 adults with RA, patients receiving etoricoxib 90 mg or 120 mg QD for 8 weeks achieved similar improvements in the primary endpoints of patient and investigator global assessment of disease activity. Both treatment groups showed significant improvements compared with placebo (average change from baseline p < 0.05) (CitationCurtis et al 2001). Moreover, in extensions to this study the efficacy of etoricoxib 90 mg or 120 mg QD was maintained, and was similar to that of diclofenac 50 mg TID, over the subsequent 166 weeks (CitationCurtis et al 2001; CitationCurtis, Losada, et al 2003). Since etoricoxib 90 mg QD produced maximal benefit in this study, with no additional efficacy at higher doses, this is considered the optimal dosage for RA (CitationEMEA 2005a).

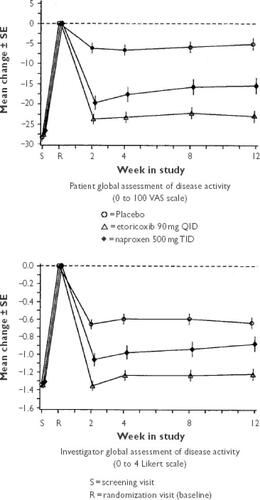

In a randomized study in 816 patients with RA in the US, etoricoxib 90 mg QD was more effective than naproxen 500 mg TID (p < 0.05) or placebo (p < 0.01) over 12 weeks for all primary and most secondary endpoints (), including the percentage of patients who achieved an American College of Rheumatology 20% Response Criteria (ACR20) response (57.9%, 46.8%, and 27.4%, respectively) (CitationMatsumoto et al 2002). The efficacy of etoricoxib was evident after 2 weeks (CitationMatsumoto et al 2002), and was similar in patients with or without concomitant DMARD and/or low-dose corticosteroid therapy (CitationMatsumoto, Zhao, et al 2003).

Figure 2 Global assessment results for etoricoxib versus placebo and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. In this randomized, double-blind, controlled study, 816 adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis were randomized to receive etoricoxib 90 mg QD (n = 323), naproxen 500 mg BID (n = 170) or placebo (n = 323) for 12 weeks. Etoricoxib demonstrated superior efficacy on all primary endpoints compared with naproxen (p < 0.05) or placebo (p < 0.01). Efficacy was evident after 2 weeks and was maintained throughout the study period, as illustrated here for two primary endpoints: patient global assessment of disease activity (top panel) and investigator global assessment of disease activity (bottom panel). Copyright © 2003. Reproduced with permission from CitationMatsumoto AK, Melian A, Mandel DR, et al. 2002. A randomized, controlled, clinical trial of etoricoxib in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol, 29:1623–30.

Etoricoxib exhibited comparable efficacy versus placebo in a duplicate international study (n = 891), although there was no significant difference between etoricoxib and naproxen. This discrepancy in results between the US and international studies may be due to variances in the use of concomitant therapies or result from underlying medical or cultural differences between the populations (CitationCollantes et al 2002). Extensions of the US and international studies showed that the efficacy of etoricoxib and naproxen was maintained through 52 weeks (CitationMatsumoto, Collantes, et al 2003).

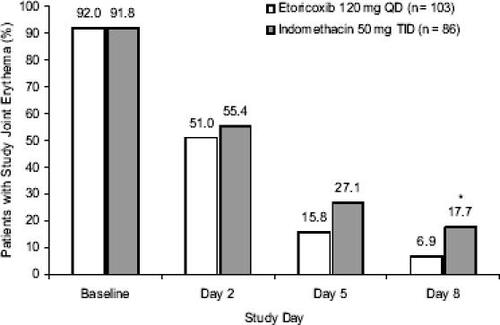

Etoricoxib in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis

Within the EU, etoricoxib is approved for the treatment of acute gouty arthritis at a dosage of 120 mg QD during the acute symptomatic period (CitationEMEA 2005a). This approval is based on the results of two clinical trials which indicate that etoricoxib and indomethacin have comparable efficacy in treating this painful condition. (CitationRubin et al 2004; CitationSchumacher et al 2002) Duplicate randomized studies enrolling a total of 339 patients presenting with acute gout showed that etoricoxib 120 mg QD or indomethacin 50 mg TID for 8 days produced comparable improvements in pain in the affected joint, patient and investigator assessments of global treatment response, and joint tenderness and swelling (CitationRubin et al 2004; CitationSchumacher et al 2002). The onset of pain relief was rapid, with similar benefit reported within 4 hours of the first dose of etoricoxib or indomethacin (CitationRubin et al 2004; CitationSchumacher et al 2002). An exploratory analysis in one study (n = 189) showed that etoricoxib produced significantly greater resolution of erythema after 8 days compared with indomethacin (p = 0.038) () (CitationRubin et al 2004), and post-hoc analysis of both studies indicated that the effectiveness of etoricoxib was due to significant antiinflammatory and analgesic activity, and not natural resolution of the disease (CitationBoice et al 2004).

Figure 3 Improvement in study joint erythema in patients with acute gout treated with etoricoxib or indomethacin for 8 days. This randomized, double-blind study compared the efficacy of etoricoxib 120 mg QD versus indomethacin 50 mg TID in 189 patients experiencing an acute attack (≤ 48 hours) of gout. The treatments produced comparable efficacy on all primary and secondary endpoints; however, a prespecified exploratory analysis illustrated here showed that etoricoxib was associated with a greater reduction in the incidence of erythema than indomethacin, with the different reaching statistical significance at completion of the study period. Copyright © 2004. Reproduced with permission from CitationRubin BR, Burton R, Navarra S, et al. 2004. Efficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120 mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50 mg three times daily in acute gout: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum, 50:598–606.

* p < 0.05.

Etoricoxib in the treatment of other painful conditions

The efficacy of etoricoxib has been established in a variety of other painful conditions including ankylosing spondylitis (AS), LBP, acute postoperative pain, and primary dysmenorrhea. In a randomized study in 387 patients with AS, etoricoxib 90 mg or 120 mg QD showed superior efficacy to naproxen 500 mg twice daily (BID) (p < 0.05) or placebo (p < 0.001) at 6 weeks with respect to spinal pain, global disease activity, and function (Citationvan der Heijde et al 2005). Significant pain relief versus placebo was observed within 4 hours of the first dose of etoricoxib 90 mg QD and following the second dose of etoricoxib 120 mg QD, and superior efficacy versus naproxen was maintained over 52 weeks. In a post-hoc analysis of data from this study, etoricoxib and naproxen improved axial symptoms in patients with or without peripheral disease, although patients without peripheral arthritis showed greater spinal improvement (CitationGossec et al 2005). In addition, a small study (n = 22) suggested that etoricoxib 90 mg QD may reduce the need for biologic therapy in patients with severe previously NSAID-refractory AS (CitationJarrett et al 2004).

Duplicate 12-week studies in a total of 644 patients with chronic LBP showed that etoricoxib 60 or 90 mg QD produced significant improvements in pain intensity relative to placebo at the primary 4-week time point (p < 0.001), and in most secondary endpoints at 12 weeks (CitationBirbara et al 2003; CitationPallay et al 2004). Clinical benefit was achieved as early as 1 week and was maintained throughout the 3 months of the study, with no significant differences between etoricoxib dosage groups. In 1147 patients with acute LBP who completed an open, nonrandomized 6-week study of etoricoxib 60 to 120 mg QD, improvements from baseline in physical activity were observed at 2 weeks and improvements in lumbar pain and functional capacity were seen at 6 weeks (p < 0.001, each comparison) (CitationHernandez-Garduño et al 2005).

Etoricoxib is as effective as high-dose diclofenac in treating chronic LBP. In a 4-week, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study of 446 patients with chronic LBP (Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders Class 1 or 2), etoricoxib 60 mg QD was as effective as diclofenac 50 mg TID in relieving LBP as assessed by the Lower Back Pain Intensity Scale (LBP-IS). The time-weighted average change from baseline over 4 weeks for the LBP-IS was 33 mm in each group (95% confidence interval [CI] –36.25, –29.63). Both etoricoxib and diclofenac improved measures of physical functioning, and were well-tolerated throughout the trial (CitationZerbini et al 2005).

A randomized single dose-response study in 398 patients with moderate to severe acute pain following dental surgery showed that etoricoxib 120 mg was the optimal dosage for this indication. Overall, 93.4% of patients receiving a single dose of etoricoxib 120 mg had perceptible pain relief, with a median time to pain relief of 0.4 hours and median time to use of rescue medication of more than 24 hours (p < 0.001 versus placebo and p < 0.05 versus etoricoxib 60 mg for all comparisons) (CitationMalmstrom, Sapre, et al 2004). Subsequent studies have shown that a single dose of etoricoxib 120 mg has greater overall analgesic efficacy in this setting than oxycodone 10 mg/acetaminophen 650 mg (CitationChang et al 2004; CitationMalmstrom et al 2005) or codeine 60 mg/acetaminophen 600 mg (CitationMalmstrom, Kotey, et al 2004; CitationMalmstrom et al 2005), and comparable efficacy to naproxen 550 mg (CitationMalmstrom, Kotey, et al 2004). A recent study (n = 228) also demonstrated comparable pain relief with a single dose of etoricoxib 120 mg or extended-release naproxen 1000 mg administered within 72 hours of knee or hip replacement surgery, and superior analgesic efficacy with etoricoxib 120 mg QD versus placebo over 7 days following surgery (p < 0.001) (no active comparator group was available for the latter analysis) (CitationRasmussen et al 2004). Finally, a single dose of etoricoxib 120 mg showed analgesic efficacy superior to placebo, and comparable with naproxen 550 mg, in a randomized study in 73 women with primary dysmenorrhea (CitationMalmstrom et al 2003).

Tolerability and patient acceptability

Clinical trial data indicates that etoricoxib has a favorable tolerability profile and is associated with an improved quality of life (CitationHunsche et al 2002; CitationRamos-Remus et al 2004). Moreover, clinical trial extensions showed that the tolerability profile of etoricoxib was maintained without notable safety findings during prolonged treatment for a total of 52 to 174 weeks (CitationFisher et al 2001, Citation2003; CitationCurtis, Losada, et al 2003; CitationMatsumoto, Collantes, et al 2003; CitationReginster et al 2004; Citationvan der Heijde et al 2005). Based on clinical experience with other NSAIDs, issues of particular interest in etoricoxib trials included gastrointestinal tolerability, renovascular effects, and cardiovascular safety.

Gastrointestinal tolerability

Several clinical trials reported superior gastrointestinal tolerability with etoricoxib compared with traditional NSAIDs. A 12-week study in 501 patients with OA showed that etoricoxib 60 mg QD was associated with a lower rate of ‘nuisance’ gastrointestinal adverse events (eg, abdominal pain, dyspepsia) (20.1% versus 33.0%) and fewer upper gastrointestinal perforations, ulcers, or bleeding (PUBs) (0 versus 5 events) compared with naproxen 500 mg BID (CitationLeung et al 2002). Moreover a pooled analysis of this and a duplicate study indicates that the favorable gastrointestinal tolerability of etoricoxib is maintained during long-term treatment over 138 weeks (0.8% versus 5.9% PUBs) (CitationReginster et al 2004). The EDGE study reported a lower rate of discontinuations due to gastrointestinal adverse events with etoricoxib 90 mg QD than with diclofenac 50 mg TID in patients with OA (relative risk [RR], 0.50; p < 0.001) (CitationBaraf et al 2004). In this study consistent benefit was also observed within patient subgroups at risk for gastrointestinal adverse events, including patients using concomitant aspirin or continuing or initiating gastroprotective therapy (CitationBaraf et al 2005a). There was no difference with respect to the incidence of PUBs or new use of gastroprotective agents in the EDGE study (CitationMerck 2005); however, this was not a prespecified endpoint and the analysis was confounded by use of aspirin and gastroprotective agents. An 8-day study in 189 patients with acute gout showed that etoricoxib 120 mg QD was associated with a lower rate of drug-related gastrointestinal adverse events than indomethacin 50 mg TID (7.8% versus 18.6%) (CitationRubin et al 2004). A 4-week safety study in 62 healthy volunteers demonstrated that daily fecal blood loss with etoricoxib 120 mg QD was comparable with placebo and lower than with ibuprofen 800 mg TID (p < 0.001) (CitationHunt, Harper, Callegari, et al 2003).

Results from two large 12-week endoscopy studies in patients with OA or RA showed that etoricoxib 120 mg QD was associated with a lower cumulative incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers (≥ 3 mm) and a smaller increase in gastroduodenal erosions than naproxen 500 mg BID (CitationHunt, Harper, Callegari, et al 2003) or ibuprofen 800 mg TID (CitationHunt, Harper, Watson, et al 2003) (p < 0.01 for each comparison). In addition, results from several large pooled analyses also support the favorable gastrointestinal tolerability profile of etoricoxib (CitationHunt, Harper, Watson, et al 2003; CitationWatson et al 2004; CitationRamey et al 2005). An analysis of 5441 patients with OA, RA, or AS from 10 clinical trials, showed that etoricoxib 60 to 120 mg QD was associated with a lower incidence of PUBs than traditional NSAIDs (ibuprofen 800 mg TID, diclofenac 50 mg TID, naproxen 500 mg BID) () (CitationRamey et al 2005). The superior PUB profile of etoricoxib during the first year of treatment in the pooled population was driven primarily by comparison with naproxen (CitationMerck 2005). In the pooled analysis, as well as the EDGE study, the reduction in PUBs with etoricoxib versus traditional NSAID comparator(s), appeared to be negated in patients receiving concomitant aspirin therapy (CitationMerck 2005).

Table 1 Pooled analysis of upper gastrointestinal safety: perforations ulcers and bleeds with etoricoxib versus nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)Table Footnote* (CitationRamey et al 2005)

Data from 4782 patients with OA, RA, chronic LBP, or AS, showed that etoricoxib 60 mg to 120 mg QD was associated with less discontinuation due to dyspepsia (p = 0.007) and lower new use of gastroprotective agents (p < 0.001) compared with the NSAIDs diclofenac and naproxen (mean follow-up 80.5 versus 73.1 weeks) (CitationWatson et al 2004).

Renovascular and cardiovascular tolerability

All selective and traditional NSAIDs inhibit prostanoid biosynthesis (CitationWarner and Mitchell 2004); however, it has been hypothesized that selective suppression of COX-2-dependent synthesis of prostacyclin (a vasodilator and inhibitor of platelet aggregation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation) without concomitant inhibition of COX-1-dependent synthesis of thromboxane A2 (a vasoconstrictor and promoter of platelet aggregation and vascular proliferation), may increase the risk of cardiovascular adverse effects owing to thromboembolism or elevated blood pressure in patients predisposed to such events (CitationFitz Gerald 2002, Citation2004; CitationClark et al 2004; CitationWarner and Mitchell 2004). Clinical trials have suggested that long term use of celecoxib and rofecoxib may be associated with more cardiovascular events than placebo or nonselective NSAIDs (CitationBombardier et al 2000; CitationFDA 2001; CitationBresalier et al 2005; CitationSolomon et al 2005), and this has led to the market withdrawal of rofecoxib worldwide. However, there has been uncertainty over these findings as a result of the small number of events reported and methodological problems with the trials. For example, the trials were statistically underpowered to evaluate thrombotic events, comparisons between trials were limited by the different proportions of patients with RA (an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease [CitationSolomon et al 2003]), and concomitant aspirin therapy or use of a naproxen comparator group may have had a confounding cardioprotective effect (CitationFitz Gerald 2002; CitationClark et al 2004; CitationWarner and Mitchell 2004).

The outstanding questions surrounding the cardiovascular safety of traditional NSAIDs and selective COX-2 inhibitors are important matters that greatly impact clinical care for patients such as those with RA who require effective and long-term pain and symptom relief. The available evidence does not conclusively support a mechanistic effect of COX-2 inhibitors on hemostasis. Of note, recent research has shown that acetaminophen also significantly inhibits prostacyclin and thromboxane synthesis (CitationSchwartz et al 2006), suggesting that there is a general lack of information regarding the mechanistic effects of commonly used analgesic agents.

Etoricoxib appears to be associated with a low incidence of renovascular adverse events (hypertension, lower extremity edema, or congestive heart failure) consistent with fluid retention observed with all selective and nonselective NSAIDs (CitationCurtis et al 2004). The EDGE study reported a numerically higher incidence of hypertension-related adverse events and a significantly higher percentage of patients discontinuing therapy with etoricoxib 90 mg QD compared with diclofenac 50 mg TID (11.7% versus 5.9%, respectively, for adverse events; 2.3% versus 0.7%, respectively, for discontinuations, RR 1.60 with 95% CI 1.06, 2.18) (CitationMerck 2005). In addition, a higher rate of new hypertension medication use was reported with etoricoxib compared with diclofenac (27.4 versus 22.3 events per 100 patient-years; RR 1.24, p < 0.001). Serious hypertension-related adverse events were rare (CitationMerck 2005). In a pooled analysis of 12-week data from 4770 patients with OA, RA, or chronic LBP, the risk of renovascular adverse events associated with etoricoxib 60 mg, 90 mg, or 120 mg QD was low and generally similar to that observed with naproxen 500 mg BID or ibuprofen 800 mg TID (CitationCurtis et al 2004). It is therefore important to monitor blood pressure in all patients taking NSAIDs (CitationFDA 2005a).

Analysis of pooled data from more than 6700 patients (representing approximately 6500 patient-years of observation) suggested that treatment with etoricoxib ≥ 60 mg QD was not associated with an excess risk of serious thrombotic cardiovascular adverse events (fatal or nonfatal cardiac, cerebrovascular, or peripheral vascular events confirmed by a blinded external committee) compared with placebo (RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.32, 3.81) or non-naproxen NSAIDs (diclofenac 50 mg TID or ibuprofen 800 mg TID; RR 0.83, 95% CI, 0.26, 2.64) (CitationCurtis, Mukhopadhyay, et al 2003). There were fewer such events associated with naproxen 500 mg BID, which was evaluated separately from other traditional NSAIDs because of its potential cardio-protective activity (etoricoxib versus naproxen RR 1.70; 95% CI 0.91, 3.18) (CitationCurtis, Mukhopadhyay, et al 2003).

The EDGE study revealed no clear difference between etoricoxib and diclofenac with respect to the overall incidence of confirmed thrombotic cardiovascular events (1.25 versus 1.15 events per 100 patient years, respectively; RR 1.07) (CitationBaraf et al 2005b). There were slight differences in the profile of cardiovascular events with etoricoxib versus diclofenac (eg, 26 versus 19 cardiac events); however, the numbers were too small to draw firm conclusions (CitationBaraf et al 2005b; CitationMerck 2005) and any potential difference appeared to be ameliorated in patients receiving concomitant aspirin therapy (CitationFDA 2005c).

The MEDAL Program (Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term) comparing etoricoxib with diclofenac in over 34 000 RA and OA patients from three component clinical studies, EDGE (completed), EDGE 2 and MEDAL (both studies ongoing), over more than 18 months (with some patients receiving treatment for up to 40 months) is underway. This program is the first noninferiority comparison of thrombotic cardiovascular events between a traditional NSAID (diclofenac) and a selective COX-2 inhibitor (etoricoxib), and it will provide further insight into the long-term cardiovascular safety of etoricoxib and diclofenac. Additionally, as part of an ongoing safety surveillance effort, a thrombotic cardiovascular event procedure was established in 1998 prior to phase IIb etoricoxib studies in order to collect cardiovascular safety data for etoricoxib, NSAID comparators and placebo across etoricoxib’s clinical development program.

Analysis of the available cardiovascular data for all COX-2 inhibitors, including etoricoxib, has led both the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) to request the addition of warnings about the potential for increased cardiovascular risk in the prescribing information for these agents (CitationEMEA 2005b; CitationFDA 2005b). In the US, this directive has been extended to apply to all NSAIDs (except aspirin), irrespective of their COX-2 selectivity (CitationFDA 2005b). These warnings highlight the need for careful patient selection based on evaluation of the benefits and risks of therapy.

Patient support/disease management programs

American College of Rheumatologists (ACR) guidelines indicate that pharmacologic therapies such as NSAIDs, DMARDs, and/or glucocorticoids should be used alongside nonpharmacologic strategies (eg, patient education, joint exercise) in the management of RA (CitationACRRAG 2002). COX-2 inhibitors may be selected for drug treatment in patients at risk of peptic ulceration (CitationACRRAG 2002). Alternatively, low-dose prednisone therapy, a nonacetylated salicylate, or a nonselective NSAID with concomitant gastroprotective therapy to reduce gastroduodenal ulceration (eg, proton pump inhibitor, high-dose H2 blocker, or oral prostaglandin analog) may be used in high risk patients (CitationACRRAG 2002). However, routine use of H2 blockers for dyspepsia is not recommended due to the potential risk of other gastrointestinal complications (CitationACRRAG 2002). Moreover, patients receiving gastroprotective therapy may still be at risk of lower gastrointestinal tract events. ACR guidelines recommend that pharmacologic therapy for OA of the hip or knee should be considered an adjunct to nonpharmacologic strategies including patient education, personalized social support, weight loss, and appropriate physical activity (ACRSOG 2002). COX-2 inhibitors are considered useful among patients who do not achieve symptom relief with acetaminophen, and in those where adverse events to acetaminophen or nonselective NSAIDs are likely or have occurred (ACRSOG 2002). Analgesics, including selective COX-2 inhibitors, are an important component of the management of a variety of other musculoskeletal pain syndromes (CitationArgoff 2002).

Etoricoxib, like all COX-2 inhibitors, may be associated with a small increase in the risk of some cardiovascular adverse events, and this needs to be weighed carefully against the benefits of treatment, particularly in patients with underlying cardiovascular risk factors. European etoricoxib prescribing guidelines indicate that treatment is contra-indicated in patients with congestive heart failure, poorly controlled hypertension, established ischemic heart disease, peripheral arterial disease and/or cerebrovascular disease. The treatment should be given for the shortest duration possible at the lowest effective daily dose, and the need for and response to treatment should be reevaluated periodically (CitationEMEA 2005a). This is in line with US guidelines for all prescription and nonprescription NSAIDs (excluding aspirin) (CitationFDA 2005d).

Economic evaluation in the UK showed that etoricoxib was a cost-effective option in patients with RA or OA compared with nonselective NSAIDs plus gastroprotective therapy (proton pump inhibitors or misoprostol) (CitationMoore et al 2004). It was also cost effective compared with nonselective NSAIDs in patients with AS in the UK (CitationJansen et al 2005). Etoricoxib is associated with higher treatment costs than indomethacin for acute gouty arthritis, but this may be counterbalanced by indirect cost savings and improved quality of life due to fewer drug-related adverse effects (CitationMartin et al 2005).

Conclusion

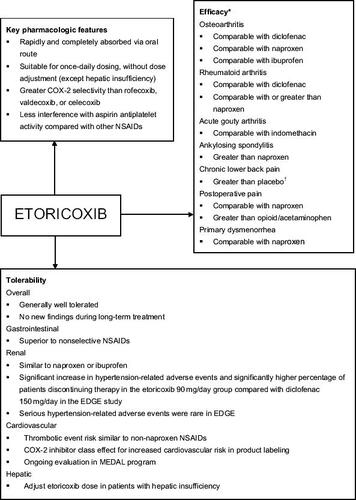

A clinical summary for etoricoxib is presented in . Etoricoxib is a COX-2 inhibitor with a high degree of selectivity for its target. It provides an alternative to other selective and traditional NSAIDs in treating patients with arthritis and other painful conditions. Etoricoxib may be given to a broad range of patients without need for dosage adjustment, except in cases of hepatic insufficiency. It is suitable for once-daily administration, which may facilitate patient compliance with treatment. Clinical trials have shown that etoricoxib has at least comparable efficacy and greater gastrointestinal tolerability compared with nonselective NSAIDs, and may therefore be particularly suitable for patients with gastrointestinal risk factors. Results from the MEDAL Program will provide further insight into the efficacy and gastrointestinal, renovascular, and cardiovascular tolerability of etoricoxib. In summary, etoricoxib provides an effective therapeutic alternative in the management of arthritic and painful conditions. As for all drugs, the benefits and risks of treatment should be evaluated carefully for each patient.

Figure 4 Clinical summary of etoricoxib in arthritis and pain management.

*Greater efficacy defined here as a statistically significant benefit with etoricoxib versus active comparator in an efficacy study. † An active comparator study has not been performed.

Abbreviations

| ACR | = | American College of Rheumatology |

| 20 | = | American College of Rheumatology 20% Response Criteria |

| AS | = | ankylosing spondylitis |

| BID | = | twice daily |

| CI | = | confidence interval |

| COX | = | cyclooxygenase |

| CYP | = | cytochrome P450 |

| DMARD | = | disease-modifying antirheumatic drug |

| EDGE | = | Etoricoxib versus Diclofenac sodium Gastrointestinal tolerability and Effectiveness study |

| EMEA | = | European Medicines Agency |

| FDA | = | United States Food and Drug Administration |

| IC50 | = | inhibitory concentration of 50% |

| LBP | = | low back pain |

| MEDAL | = | Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term study |

| NSAID | = | nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| OA | = | osteoarthritis |

| PGADS | = | patient’s global assessment of disease status |

| QD | = | once daily |

| RA | = | rheumatoid arthritis |

| RR | = | relative risk |

| TID | = | three times daily |

| WOMAC | = | Western Ontario and McMaster’s University OA index. |

References

- AgrawalNGMatthewsCZMazenkoRSPharmacokinetics of etoricoxib in patients with renal impairmentJ Clin Pharmacol2004a44485814681341

- AgrawalNGMatthewsCZMazenkoRSThe effects of modifying in vivo cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) activity on etoricoxib pharmacokinetics and of etoricoxib administration on CYP3A activityJ Clin Pharmacol2004b4411253115342613

- AgrawalNGPorrasAGMatthewsCZSingle- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of etoricoxib a selective inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-2, in manJ Clin Pharmacol2003432687612638395

- AgrawalNGRoseMJMatthewsCZPharmacokinetics of etoricoxib in patients with hepatic impairmentJ Clin Pharmacol20034311364814517196

- [ACRCCG] American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Clinical GuidelinesGuidelines for the initial evaluation of the adult patient with acute musculoskeletal symptomsArthritis Rheum199639188546717

- [ACRSOG] American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis GuidelinesRecommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 updateArthritis Rheum20004319051511014340

- [ACRRAG] American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis GuidelinesGuidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 UpdateArthritis Rheum2002463284611840435

- ArgoffCEPharmacologic management of chronic painJ Am Osteopath Assoc2002102S21712356037

- BarafHFuentealbaCGreenwaldMGastrointestinal tolerability of etoricoxib compared with diclofenac sodium in subgroups of patients at risk for gastrointestinal side effects from the edge study [abstract]2005aAnnual Meeting of the European League Against Rheumatism8–11 June 2005Vienna, Austria SAT0277

- BarafHFuentealbaCGreenwaldMCardiovascular event rates with etoricoxib and comparator NSAIDs in the edge study and the overall etoricoxib development program [abstract]2005bAnnual Meeting of the European League Against Rheumatism8-11 June 2005Vienna, Austria SAT0276

- BarafHSBFuentealbaCGreenwaldMTolerability and effectiveness of etoricoxib compared with diclofenac sodium in patients with osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled study (EDGE trial) [abstract]2004American College of Rheumatology 68th Annual Scientific Meeting16–21 October 2004San Antonio, TX, USA 832

- BirbaraCAPuopoloADMunozDRTreatment of chronic low back pain with etoricoxib, a new cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitor: improvement in pain and disability—a randomized, placebo-controlled, 3-month trialJ Pain200343071514622687

- BoiceJANgJRubinBRThe spontaneous resolution of acute gouty arthritis does not significantly contribute to the potent and comparable antiinflammatory and analgesic effect of etoricoxib of indomethacin over the first four days of treatment [abstract]2004American College of Rheumatology 68th Annual Scientific Meeting16–21 October 2004San Antonio, TX USA 809

- BombardierCLaineLReicinAComparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study GroupN Engl J Med20003431520811087881

- BresalierRSSandlerRSQuanHCardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trialN Engl J Med2005352109210215713943

- Catella-LawsonFReillyMPKapoorSCCyclooxygenase inhibitors and the antiplatelet effects of aspirinN Engl J Med200134518091711752357

- ChangDJDesjardinsPJKingTRThe analgesic efficacy of etoricoxib compared with oxycodone/acetaminophen in an acute postoperative pain model: a randomized, double-blind clinical trialAnesth Analg2004998071515333415

- ClarkDWLaytonDShakirSADo some inhibitors of COX-2 increase the risk of thromboembolic events?: Linking pharmacology with pharmacoepidemiologyDrug Saf2004274275615141995

- CollantesECurtisSPLeeKWA multinational randomized, controlled, clinical trial of etoricoxib in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [ISRCTN25142273]BMC Fam Pract200231012033987

- CurtisSPLosadaBBosi-FerrazMEtoricoxib and diclofenac demonstrate similar efficacy in a 174-week randomized study of rheumatoid arthritis patients [poster]2003aAmerican College of Rheumatology 67th Annual Scientific Meeting23–28 October 2003Orlando, FL, USA213

- CurtisSPMaldonado-CoccoJLosadaBRTreatment with etoricoxib (MK-0663), a COX-2-selective inhibitor, resulted in maintenance of clinical improvement in rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]2001Annual Meeting of the European League Against Rheumatism13– 16 June 2001Prague, Czech Republic FRI0030

- CurtisSPBockowBFisherCEtoricoxib in the treatment of osteoarthritis over 52-weeks: a double-blind, active-comparator controlled trial [NCT00242489]BMC Musculoskelet Disord200565816321158

- CurtisSPMukhopadhyaySRameyDCardiovascular safety summary associated with the etoricoxib development programArthritis Rheum2003b48SupplS616

- CurtisSPNgJYuQRenal effects of etoricoxib and comparator nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in controlled clinical trialsClin Ther200426708314996519

- CushJJKavanaughAMattesonELThe safety of COX-2 inhibitors. Deliberations from the February 16–18, 2005, FDA meeting [online]Am Coll Rheumatol2006 Accessed on 12 January 2006 URL: http://www.rheumatology.org/publications/hotline/0305NSAIDs.asp

- DallobAHawkeyCJGreenbergHCharacterization of etoricoxib, a novel, selective COX-2 inhibitorJ Clin Pharmacol2003435738512817520

- DrazenJMCOX-2 inhibitors — a lesson in unexpected problemsN Engl J Med20053521131215713947

- [EMEA] European Medicines AgencyEtoricoxib summary of product characteristics [online]2005a Accessed 13 January 2006 URL: http://www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/epar/Etoricoxib.pdf

- [EMEA] European Medicines AgencyPress release: European Medicines Agency concludes action on COX-2 inhibitors [online]2005b Accessed 13 January 2006 URL: http://www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/press/pr/20776605en.pdf

- FisherCBockowBCurtisSPResults of a 190-week randomized study demonstrated similar efficacy of etoricoxib compared with diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis (OA) [abstract]2003Annual Meeting of the European League Against Rheumatism18–21 June 2003Lisbon, Portugal FRI0256

- FisherCACurtisSPResnickHTreatment with etoricoxib, a COX-2 selective inhibitor, resulted in clinical improvement in knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA) over 52 weeks [abstract]Arthritis Rheum200144Suppl 9S135 495

- Fitz GeraldGACardiovascular pharmacology of nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and coxibs: clinical considerationsAm J Cardiol20028926D32D

- Fitz GeraldGACoxibs and cardiovascular diseaseN Engl J Med200435117091115470192

- [FDA] Food and Drug AdministrationConsultation NDA 21-042, S-007. Review of cardiovascular safety database: rofecoxib [online]2001 Accessed 7 July 2005 URL: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3677b2_06_cardio.pdf

- [FDA] Food and Drug AdministrationCOX-2 selective (includes Bextra, Celebrex, and Vioxx) and non-selective non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [online]2005a Accessed 24 February 2006 URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/COX2.htm

- [FDA] Food and Drug AdministrationCOX-2 selective and non-selective non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [online]2005b Accessed 7 July 2005 URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/COX2/default.htm

- [FDA] Food and Drug AdministrationFDA presentation: analysis of cardiovascular thromboembolic events with etoricoxib [online]2005c Accessed 7 July 2005 URL: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/05/transcripts/2005-4090T2.htm

- [FDA] Food and Drug AdministrationFDA Public Health Advisory: FDA announces important changes and additional warnings for COX-2 selective and non-selective non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [online]2005d Accessed 23 June 2005 URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/advisory/COX2.htm

- FrizzieroLGraningerWLangevitzPEtoricoxib is effective in osteoarthritis patients with different levels of baseline severity of the disease [poster]2004Annual European Congress of Rheumatology9– 12 June 2004Berlin, Germany FRI0429

- GossecLvan derHDMelianAThe efficacy of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition by etoricoxib and naproxen on the axial manifestations of ankylosing spondylitis in the presence of peripheral arthritisAnn Rheum Dis2005641563715731291

- GottesdienerKSchnitzerTFisherCResults of a randomized, dose-ranging trial of etoricoxib in patients with osteoarthritisRheumatology (Oxford)20024110526112209041

- Hernandez-GarduñoAVázquez-LeducAQuerol-VinagreJVClinical evaluation following treatment with etoricoxib (60, 90 and 120mg once a day) in patients with acute low back pain: a cohort, open, non-randomized, multicenter study [abstract]2005Annual Meeting of the European League Against Rheumatism8–11 June 2005Vienna, Austria SAT0362

- HunscheEGelingOKongSXImpact of etoricoxib, a novel COX-2 inhibitor, on social and emotional quality of life of patients with osteoarthritisOsteoporosis Int200213S20

- HuntRHHarperSCallegariPComplementary studies of the gastrointestinal safety of the cyclo-oxygenase-2-selective inhibitor etoricoxibAliment Pharmacol Ther2003a172011012534404

- HuntRHHarperSWatsonDJThe gastrointestinal safety of the COX-2 selective inhibitor etoricoxib assessed by both endoscopy and analysis of upper gastrointestinal eventsAm J Gastroenterol2003b9817253312907325

- JansenJPHunscheEChoyEEconomic evaluation of etoricoxib versus non-selective NSAIDs in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis in the UK [abstact]2005Annual Meeting of the European League Against Rheumatism8–11 June 2005Vienna, Austria FRI0475

- JarrettSJMcgonagleDMarzo-OrtegaHEtoricoxib reduces the need for biologic therapy in ankylosing spondylitis (AS) but has no effect on magnetic resonance imaging. Results from an open study [abstract]2004American College of Rheumatology 68th Annual Scientific Meeting16–21 October 2004San Antonio, TX, USA 1634

- KassahunKMcIntoshISShouMRole of human liver cytochrome P4503A in the metabolism of etoricoxib, a novel cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitorDrug Metab Dispos2001298132011353749

- LeungATMalmstromKGallacherAEEfficacy and tolerability profile of etoricoxib in patients with osteoarthritis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo and active-comparator controlled 12-week efficacy trialCurr Med Res Opin200218495812017209

- MalmstromKAngJFrickeJRThe analgesic effect of etoricoxib relative to that of two opioid-acetaminophen analgesics: a randomized, controlled single-dose study in acute dental impaction painCurr Med Res Opin200521141915881486

- MalmstromKKoteyPCichanowitzNAnalgesic efficacy of etoricoxib in primary dysmenorrhea: results of a randomized, controlled trialGynecol Obstet Invest20035665912900528

- MalmstromKKoteyPCoughlinHA randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study comparing the analgesic effect of etoricoxib to placebo, naproxen sodium, and acetaminophen with codeine using the dental impaction pain modelClin J Pain2004a201475515100590

- MalmstromKSapreACouglinHEtoricoxib in acute pain associated with dental surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-and active comparator-controlled dose-ranging studyClin Ther2004b266677915220011

- MartinMHunscheEBoiceJAn economic cost analysis of etoricoxib versus indomethacin in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis in the UK [abstract]2005Annual Meeting of the European League Against Rheumatism8-11 June 2005Vienna, Austria FRI0472

- MatsumotoAKCollantesEMelianATreatment with etoricoxib resulted in clinical improvement of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in two randomized active comparator-controlled 52-week trials [abstract]2003aAnnual Meeting of the European League Against Rheumatism18–21 June, 2003Lisbon, Portugal THU0249

- MatsumotoAKMelianAMandelDRA randomized, controlled, clinical trial of etoricoxib in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritisJ Rheumatol20022916233012180720

- MatsumotoAKZhaoPLCichanowitzNEtoricoxib is efficacious in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on concomitant therapy with disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and/or low-dose corticosteroids [poster]2003bAmerican College of Rheumatology 67th Annual Scientific Meeting23–28 October 2003Orlando, FL, USA 209

- MerckBriefing Package for NDA 21-389: Etoricoxib [online]2005 Accessed 23 June 2005 URL: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/05/briefing/2005-4090B1_31_AA-FDA-Tab-T.pdf

- MooreAPhillipsCHunscheEEconomic evaluation of etoricoxib versus non-selective NSAIDs in the treatment of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis patients in the UKPharmacoeconomics2004226436015244490

- OuelletMRiendeauDPercivalMDA high level of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor selectivity is associated with a reduced interference of platelet cyclooxygenase-1 inactivation by aspirinProc Natl Acad Sci U S A20019814583811717412

- PallayRMSegerWAdlerJLEtoricoxib reduced pain and disability and improved quality of life in patients with chronic low back pain: a 3 month, randomized, controlled trialScand J Rheumatol2004332576615370723

- PsatyBMFurbergCDCOX-2 inhibitors — lessons in drug safetyN Engl J Med20053521133515713946

- RameyDRWatsonDJYuCThe incidence of upper gastrointestinal adverse events in clinical trials of etoricoxib versus. non-selective NSAIDs: an updated combined analysisCurr Med Res Opin2005217152215974563

- Ramos-RemusCRHunscheEMavrosPEvaluation of quality of life following treatment with etoricoxib in patients with arthritis or low-back pain: an open label, uncontrolled pilot study in MexicoCurr Med Res Opin200420691815140335

- RasmussenGLBourneMHRhondeauSMEtoricoxib provides pain relief and reduces opioid use in post-orthopedic surgery patients [poster]2004Annual European Congress of Rheumatology9–12 June 2004Berlin, Germany SAT0130

- ReginsterJYFischerCLBeualieuAEtoricoxib demonstrates similiar efficacy and improved gastrointestinal safety compared with naproxen in two 138-week randomized studies of osteoarthritis patients [abstract]2004Annual European Congress of Rheumatology9–12 June 2004Berlin, Germany FRI0394

- RiendeauDPercivalMDBrideauCEtoricoxib (MK-0663): preclinical profile and comparison with other agents that selectively inhibit cyclooxygenase-2J Pharmacol Exp Ther20012965586611160644

- RodriguesADHalpinRAGeerLAAbsorption, metabolism, and excretion of etoricoxib, a potent and selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in healthy male volunteersDrug Metab Dispos2003312243212527704

- RubinBRBurtonRNavarraSEfficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50mg three times daily in acute gout: a randomized controlled trialArthritis Rheum20045059860614872504

- SchumacherHRJrBoiceJADaikhDIRandomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritisBMJ200232414889212077033

- SchwartzJIGreenbergHEMusserBJInhibition of prostacyclin and thromboxane biosynthesis in healthy volunteers by single and multiple doses of paracetamol (acetaminophen) [poster]2006Presented at the Annual European congress of Rheumutalogy8–11 June 2005Vienna, Austria

- SolomonDHKarlsonEWRimmEBCardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritisCirculation20031071303712628952

- SolomonSDMcMurrayJJPfefferMACardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma preventionN Engl J Med200535210718015713944

- TacconelliSCaponeML SciullimgThe biochemical selectivity of novel COX-2 inhibitors in whole blood assays of COXisozyme activityCurr Med Res Opin2002185031112564662

- van der HeijdeDBarafHSRamos-RemusCEvaluation of the efficacy of etoricoxib in ankylosing spondylitis: results of a fifty-two-week, randomized, controlled studyArthritis Rheum20055212051515818702

- WagnerJAKraftWBurkeJThe COX-2 inhibitor etoricoxib did not alter the anti-platelet of low dose aspirin in health in healthy volunteers [abstract]Arthritis Rheum200144Suppl 9S135 498

- WarnerTDMitchellJACyclooxygenases: new forms, new inhibitors, and lessons from the clinicFASEB J20041879080415117884

- WatsonDJBologneseJAYuCUse of gastroprotective agents and discontinuations due to dyspepsia with the selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor etoricoxib compared with non-selective NSAIDsCurr Med Res Opin200420189990815701208

- WiesenhutterCWBoiceJAKoAEvaluation of the comparative efficacy of etoricoxib and ibuprofen for treatment of patients with osteoarthritis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialMayo Clin Proc200580470915819283

- [WHO] World Health OrganizationWorld health report 2004 – changing history [online]2004 Accessed 27 June 2005 URL: http://www.who.int/whr/2004/en/index.html

- [WHO] World Health OrganizationChronic rheumatic conditions [online]2005 Accessed 4 March 2005 URL: http://www.who.int/chp/topics/rheumatic/en/

- ZacherJFeldmanDGerliRA comparison of the therapeutic efficacy and tolerability of etoricoxib and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritisCurr Med Res Opin2003197253614687444

- ZerbiniCOzturkZEGrifkaJEfficacy of etoricoxib 60mg/day and diclofenac 150mg/day in reduction of pain and disability in patients with chronic low back pain: results of a 4-week, multinational, randomized, double-blind studyCurr Med Res Opin20052120374916368055