Abstract

Non-selective and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been the mainstay of treatment for musculoskeletal pain of moderate intensity. However, in addition to gastrointestinal and renal toxicity, an increased cardiovascular risk may be a class effect for all NSAIDs. Despite these safety risks and the acknowledged ceiling effect of NSAIDs, many doctors still use them to treat moderate, mostly musculoskeletal pain. Recent guidelines for treating osteoarthritis and low back pain, issued by numerous professional medical societies, recommend NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors only in strictly defined circumstances, at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest possible period of time. These recent guidelines bring more focus to the usage of paracetamol and opioids. But opioids still remain under-utilized, although they are effective with minimal organ toxicity. In this setting, the atypical, centrally acting analgesic tramadol offers important benefits. Its multi-modal effect results from a dual mode of action, ie, opioid and monoaminergic mechanisms, with efficacy in both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Moreover, fewer instances of side effects such as constipation, respiratory depression, and sedation occur than with traditional opioids, and tramadol has been prescribed for 30 years for a broad range of indications. Tramadol is now regarded as the first-line analgesic for many musculoskeletal indications. In conclusion, it is recommended to better implement the more recent guidelines focusing on pain management and consider the role of tramadol in musculoskeletal pain treatment strategies.

Introduction

The focus of this article is the current treatment of musculoskeletal pain – a therapeutic area that has seen many changes over the past few years. In 2002, American Pain Society guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis recommended cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective inhibitors and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (CitationSimon et al 2002). However, the discovery that rofecoxib was linked to an increased incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke led to dramatic changes (CitationGraham 2006). At first it was thought that increased cardiovascular risk might be a class effect of COX-2 inhibitors, but it is now understood that the problem extends to the non-selective NSAIDs (CitationGraham et al 2005; CitationLee et al 2007). The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has clearly stated that a greater risk of cardiovascular events may be a class effect for all NSAIDs (CitationFDA 2005). Although long-term clinical trials have not been conducted for most NSAIDs, the FDA concludes from the available data that their use could increase cardiovascular risk. Moreover, the gastric and renal toxicity associated with these agents is well established (CitationWhelton 2000; CitationDieppe et al 2004). This paper reviews the recent guidelines for musculoskeletal pain with an emphasis on the role of an atypical opioid, tramadol, as an option.

Current guidelines

Recently, there has been a widespread re-examination of the management of musculoskeletal pain. For example, the Canadian Consensus Conference suggests that NSAIDs should be used with caution in elderly patients, who are at greatest risk of gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular side effects (CitationTannenbaum et al 2006). This Conference also suggests that elderly patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis should be treated in the context of a multi-faceted treatment plan that aims to preserve function and independence and improve quality of life. This is a good and worthwhile concept, but it is necessary to define exactly how it can be achieved.

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) has just published guidelines for the management of hip osteoarthritis (CitationZhang et al 2005). Interestingly, these state that opioid analgesics are useful alternatives in patients in whom NSAIDs – including COX-2 selective inhibitors – are contra-indicated, ineffective, and/or poorly tolerated. Nearly every set of guidelines that has appeared over the past 2 or 3 years recognizes that paracetamol and opioids have a more significant role to play in the management of chronic pain.

The European Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain (CitationAirakinsen et al 2006) conclude there is strong evidence that weak opioids relieve pain and disability in the short term in chronic low back pain patients. Notably, this is “level A” evidence comprising robust data. There is a clear suggestion that clinicians should decrease their use of organ-toxic NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, and possibly increase the prescription of opioids.

The American Geriatrics Society Panel (AGS) on Persistent Pain in Older Persons now considers that for many older patients, chronic opioid therapy may have fewer life-threatening risks than long-term daily use of NSAIDs (CitationAGS 2002). Comparing the organ toxicity of opioids and NSAIDs, this is clearly the case.

Choice of opioid

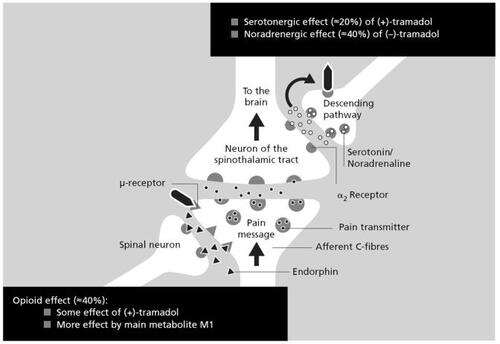

Thus guidelines produced over the past 4 years have shifted their emphasis from NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors to opioids, which clearly makes sense in the context of musculoskeletal pain. However, strong opioids are not always required. In this setting it is interesting to consider a drug that is not a monomodal opioid – tramadol. A better description of this agent is “a atypical centrally acting analgesic”. In the central nervous system (CNS), specifically in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, tramadol has a number of effects, as illustrated in . Where the first order neuron transmits a pain impulse to the second order neuron, which in turn relays the information to the brain, tramadol binds to some extent to the μ-opioid receptor (its M1 metabolite does so to a greater extent) (CitationGrond and Sablotzki 2004); this produces some of its analgesic effect and explains why, model dependent, around 40% of tramadol analgesia can be reversed by opioid antagonists (CitationRaffa et al 1992). In addition, the descending pathways responsible for pain relief rely on monoaminergic transmission, primarily via noradrenaline and serotonin. Here, tramadol binds to the descending pathway neurons, inhibiting the re-uptake of noradrenaline and serotonin, and accounting for the remaining analgesic properties (CitationDesmeules et al 1996). Thus tramadol produces a multi-modal effect with its dual mechanism of action (CitationRaffa and Friderichs 1996).

Figure 1 Synergistic effects of tramadol at the dorsal horn (CitationCollart et al 1993; CitationRaffa and Friderichs 1996).

Traditional opioids produce analgesia but also cause constipation, respiratory depression, and sedation, as well as having a significant abuse potential (CitationVickers et al 1992; CitationGrond et al 2001; CitationAtluri et al 2003; Cicero et al 2004). It has been clearly demonstrated that the combined opioid and monoaminergic mechanisms of tramadol can mitigate these adverse effects (CitationRichter et al 1985; CitationPreston et al 1991; CitationEpstein et al 2006). At the same time efficacy can be increased, particularly in patients suffering from neuropathic pain, where the enhancement of monoaminergic transmission is beneficial (CitationHarati et al 1998; CitationSindrup et al 1999; CitationChristoph et al 2007). Other side effects – dizziness, nausea, vomiting and sweating – remain at a similar level to traditional opioids (CitationAllan et al 2001; CitationGrond et al 2001). These differences are summarized in .

Table 1 Effects of traditional opioids in comparison with tramadol

The efficacy and safety of tramadol in patients with musculoskeletal pain are both very well documented (see ), and these have had an impact on treatment. A number of international guidelines now specifically recommend tramadol – not just weak opioids. The American Pain Society suggests that tramadol can be used alone, or in combination with paracetamol or NSAIDs, for therapy at any stage during the treatment of a patient with osteoarthritis. The American College of Rheumatology states that the efficacy of tramadol has been found to be comparable with that of ibuprofen in patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis, and has proven useful as adjunctive therapy in patients whose symptoms are inadequately controlled by NSAIDs (CitationDalgin et al 1997; CitationRoth 1998; CitationAltman et al 2000). The clear implication is that tramadol may be used instead of an NSAID, for example in patients with cardiac or renal complications (CitationWhelton 2000; CitationAronow 2003). If a patient is already receiving an NSAID it can be combined with tramadol in a multi-modal analgesic approach thereby permitting dose reduction of the NSAID (CitationSchnitzer et al 1999). For patients with chronic low back pain, the previously quoted European Guidelines explicitly recommend the use of “weak opioids (eg, tramadol)” in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain who do not respond to other treatment modalities (Airaksinen et al 2006).

Table 2 Controlled trials of oral tramadol in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain

Even in conditions where central sensitization is now thought to play an important role, there is support for the use of tramadol. For example, the Veterans Health Administration of the US Department of Defence considers tramadol to be a therapeutic intervention with some benefits for sufferers from fibromyalgia (CitationBuckhardt et al 2005). In the long-term care of the elderly, the American Medical Directors Association says that tramadol is a first line pharmacological treatment for chronic pain, together with paracetamol, NSAIDs, and COX-2 inhibitors (CitationAMDA 2003).

The working group on pain management

It is apparent that revised guidelines for pain management are needed, and that these will encourage greater prescription of opioids and reduced use of NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors, as well as specifically recommending tramadol. There is a Working Group on Pain Management which regularly publishes its findings, including guidelines (CitationSchnitzer 2006) (on the Internet at http://www.painworkinggroup.org). Its recommendations today differ significantly from those issued by others before 2004.

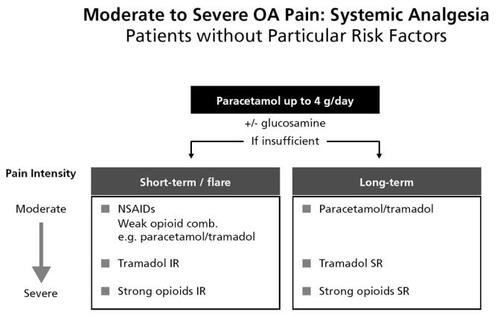

Osteoarthritis patients without particular risk factors should receive background analgesia with up to 4 g/day of paracetamol. For a short-term flare, NSAIDs or the immediate-release paracetamol–tramadol fixed combination tablet should be administered. If this does not adequately control the pain then immediate release tramadol can be administered. An immediate-release strong opioid can be considered if the patient still experiences insufficient pain relief. For long-term pain management, NSAIDs are not recommended. The regimen is similar to that for short-term treatment but there are advantages to prescribing sustained-release tramadol formulations. These treatment regimens are summarized in .

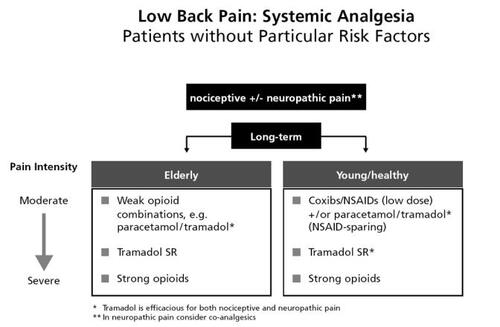

In elderly patients with low back pain who have no particular risk factors and require long term pain management, the working group recommends the use of a weak opioid plus paracetamol, or tramadol monotherapy (see ). NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors can be prescribed for young healthy adults without risk factors, but even the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (CitationEMEA 2005) now state that the smallest possible dose should be used for the shortest possible time. So the paracetamol–tramadol fixed combination tablet or tramadol sustained release may be preferred. Thus the achievement of pain management goals such as improved functioning, return to work, and a better quality of life is based largely on paracetamol and tramadol.

There is a large body of high quality evidence for using tramadol as suggested by the working group, particularly in neuropathic pain. Low back pain often has a neuropathic component, which plays a major role in the condition of patients referred to chronic pain clinics. One recent large scale study found that in an unselected cohort of chronic low back pain patients, 37% had predominantly neuropathic pain (CitationFreynhagen et al 2006). This is also the pain component that is most difficult to treat in the general practice setting.

Tramadol is increasingly gaining acceptance as it is effective against both nociceptive and neuropathic pain. There have now been a considerable number of randomized, controlled trials, and a Cochrane review, that show a high efficacy of tramadol in neuropathic pain (CitationDühmke et al 2004); the number needed to treat (NNT) compared with placebo to achieve at least 50% pain relief was 3.5 with a number needed to harm (NNH) of 7.7. Based on these favorable numbers, in the latest evidence-based algorithms for treating neuropathic pain, tramadol is very high in the sequence of drugs that should be used (CitationDworkin et al 2003; CitationFinnerup et al 2005).

Conclusion – the need for change

Many doctors still use NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors to treat musculoskeletal pain, despite the safety risks and the fact that these agents have a ceiling effect, so that continuing to increase the dose only results in a greater incidence of adverse events. Also, the inflammatory component of osteoarthritis pain is minimal (CitationBackonja 2003) – perhaps osteoarthrosis would be a more accurate term, so an anti-inflammatory drug is not needed in these patients, and NSAIDs carry the risk of organ toxicity (CitationSingh 2000; CitationLanas et al 2003; CitationDieppe et al 2004; CitationLaporte et al 2004; CitationGraham et al 2005). This was previously believed to be limited to the kidney and stomach but is now known to extend to the heart and cardiovascular system (CitationDavies et al 2006). Opioids are currently under-utilized, although they are known to be effective and have minimum organ toxicity – possibly none in most settings – even in long-term use (CitationBrown and Stinson 2004; CitationRaffa 2006). This might be of particular importance in the elderly, as they exhibit commonly already impaired or reduced organ function (CitationAuret and Schug 2005). Many guidelines have changed in the last 4 years, but have not yet been implemented in routine clinical practice.

Tramadol is now specifically recommended in musculoskeletal pain guidelines and neuropathic pain guidelines, because of its efficacy, safety, and tolerability (CitationDworkin et al 2003; CitationDühmke et al 2004; CitationFinnerup et al 2005). Clearly there is no major organ toxicity (CitationShipton 2000; CitationRaffa 2006), and its use necessarily implies an NSAID-sparing effect (CitationSchnitzer et al 1999). The improved side effect profile over traditional opioids is particularly marked in the case of constipation, which is usually the biggest problem with opioid use in the elderly. Finally, tramadol has been on the market for 30 years and clinical experience now extends to more than 5 billion patient treatment days, so the data underlying the latest guidelines are extremely robust (CitationIMS Health Inc. 1994–2005).

References

- AdlerLMcDonaldCO’BrienCA comparison of once-daily tramadol with normal release tramadol in the treatment of pain in osteoarthritisJ Rheumatol2002292196912375333

- AirakinsenOBroxJICedraschiCEuropean guidelines for the management of chronic non-specific low back painEur Spine J200615Suppl 2S192S30016550448

- AllanLHaysHJensenNHRandomised crossover trial of transdermal fentanyl and sustained release oral morphine for treating chronic non-cancer painBMJ200132211546111348910

- AltmanRDRecommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis GuidelinesArthritis Rheum20004319051511014340

- [AMDA] American Medical Directors AssociationPain management in the long-term care setting2003 Clinical practice guideline. URL: http://www.amda.com/tools/cpg/chronicpain.cfm

- [AGS] American Geriatrics Society Panel on Persistent Pain in Older PersonsThe management of persistent pain in older personsJ Am Geriatr Soc2002506 SupplS205S2412067390

- AronowWSTreatment of heart failure in older persons dilemmas with coexisting conditions: diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and arthritisCongest Heart Fail20039142712826772

- AtluriSBoswellMVHansenHCGuidelines for the use of controlled substances in the management of chronic painPain Physician200362335716880868

- AuretKSchugSAUnderutilisation of opioids in elderly patients with chronic pain: approaches to correcting the problemDrugs Aging2005226415416060715

- BackonjaM-MDefining neuropathic painAnesth Analg2003977859012933403

- BirdHAHillJStratfordMA double blind cross-over study comparing the analgesic efficacy of tramadol with pentazocine in patients with arthritisJ Drug Dev Clin Pract19957818

- BrownSCStinsonJTreatment of pediatric chronic pain with tramadol hydrochloride: siblings with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome – Hypermobility typePain Res Manage2004920911

- BuckhardtCSGoldenbergDCroffordLGuideline for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome pain in adults and childrenGlenview (IL): American Pain Society (APS)2005

- ChristophTKögelBStrassburgerWTramadol has a better potency ratio relative to morphine in neuropathic than nociceptive pain modelsDrugs in R&D20078517

- CiceroTJInciardiJAAdamsEARates of abuse of tramadol remain unchanged with the introduction of new branded and generic products: results of an abuse monitoring system, 1994–2004Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200514851915892169

- CollartLLuthyCDayerPPartial inhibition of tramadol antinociceptive effect by naloxone in manBr J Clin Pharmacol19933573

- DalginPthe TPS-OA Study Group. Comparison of tramadol and ibuprofen for the chronic pain of osteoarthritisArthritis Rheum199740Suppl 9S86 abstract

- DaviesNMReynoldsJKUndebergMRMinimizing risks of NSAIDs: cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renalExpert Rev Neurother2006616435517144779

- DesmeulesJAPiguetVCollartLContribution of monoaminergic modulation to the analgesic effect of tramadolBr J Clin Pharmacol1996417128824687

- DieppePBartlettCDaveyPBalancing benefits and harms: the example of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugsBMJ200432931415231619

- DühmkeRMCornblathDDHollingsheadJRFTramadol for neuropathic pain. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 20042004Issue 2

- DworkinRHBackonjaMRowbothamMCAdvances in neuropathic pain: Diagnosis, mechanisms and treatment recommendationsArch Neurol20036015243414623723

- [EMEA] European Medicines Agency2005 URL: http://www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/press/pr/24732305en.pdf

- EpsteinDHPrestonKLJasinskiDRAbuse liability, behavioural pharmacology, and physical dependence potential of opioids in humans and laboratory animals: Lessons from tramadolBiol Psychol20067390916497429

- [FDA]. Food and Drug Administration2005 URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/COX2/NSAIDRxtemplate.pdf; http://www.fda.gov/cder/rug/infopage/cox2/COX2qa.htm

- FinnerupNBOttoMMcQuayHJAlgorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence based proposalPain200511828930516213659

- FreynhagenRBaronRGockelUpainDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back painCurr Med Res Opin20062219112017022849

- GorolDTropfenform eines stark wirksamen Analgetikums in der DoppelblindprüfungMed Klin1983781735

- GrahamDJCOX-2 Inhibitors, Other NSAIDs, and cardiovascular risk the seduction of common senseJAMA20062961653616968830

- GrahamDYOpekunARWillinghamFFVisible Small-Intestinal Mucosal Injury in Chronic NSAID UsersClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2005355915645405

- GrondSMeertTFNoorduinHSafety and tolerability of opioid analgesia: a comparable class profile?Pain Rev2001810311

- GrondSSablotzkiAClinical pharmacology of tramadolClin Pharmacokinet20044387992315509185

- HaratiYGoochGSwensonMMaintenance of the long-term effectiveness of tramadol in treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathyJ Diabetes Complications200014657010959067

- IMS Health IncIMS Chemical Kilochem Profile and IMS Midas, 1994–2005 and Defined Daily Dose of 300 mg tramadol according to WHO [online] URL: http://www.whocc.no/atcddd/indexdatabase

- JensenEMGinsbergFTramadol versus dextropropoxyphene in the treatment of osteoarthritisDrug Invest1984821118

- LaporteJ-RIbáňnezLVidalXUpper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with the use of NSAIDs newer versus older agentsDrug Saf2004274112015144234

- LanasASerranoPBajadorERisk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with non-aspirin cardiovascular drugs, analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugsEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200315173812560762

- LeeTABartleBWeissKBImpact of NSAIDS on mortality and the effect of preexisting coronary artery disease in US veteransAm J Med200712098.e91617208086

- PavelkaKPeliskovaZStelikovaHIntraindividual differences in pain relief and functional improvement in osteoarthritis with diclofenac or tramadolClin Drug Invest19981619

- PrestonKLJasinskiDRTestaMAbuse potential and pharmacological comparison of tramadol and morphineDrug Alcohol Depend1991277172029860

- RaffaRPharmacological aspects of successful long-term analgesiaClin Rheumatol200625Suppl 1915

- RaffaRBFriderichsEThe basic science aspect of tramadol hydrochloridePain Rev1996324971

- RaffaRBFriderichsEReimannWOpioid and nonopioid components independently contribute to the mechanism of action of tramadol, an ’atypical’ opioid analgesicJ Pharmacol Exp Ther1992260275851309873

- RauckRLRuoffGEMcMillenJIComparison of tramadol and acetaminophen with codeine for long-term pain management in elderly patientsCurr Ther Res Clin Exp199455141731

- RichterWBarthHFlohéLClinical investigation on the development of dependence during oral therapy with tramadolArzneimittelforschung198535174244091874

- RothSHEfficacy and safety of tramadol HCl in breakthrough musculoskeletal pain attributed to osteoarthritisJ Rheumatol1998251358639676769

- SchnitzerTJUpdate on guidelines for the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal painClin Rheumatol200625Suppl 1S22S916741783

- SchnitzerTJGrayWLPasterRZEfficacy of tramadol in treatment of chronic low back painJ Rheumatol200027772810743823

- SchnitzerTJKaminMOlsonWHTramadol allows reduction of naproxen dose among patients with naproxen-responsive osteoarthritis painArthritis Rheum1999421370710403264

- ShiptonEAAnaesth Intensive Care2000283637410969362

- SilverfieldJCKaminMWuSCTramadol/acetaminophen combination tablets for the treatment of osteoarthritis flare pain: a multicenter, outpatient, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, add-on studyClin Ther2002242829711911558

- SimonLSLipmannAGCaudill-SlosbergMGuideline for the Management of Pain in Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis and Juvenile Chronic ArthritisGlenview USA: American Pain Society2002

- SindrupSHAndersenGMadsenCTramadol relieves pain and allodynia in polyneuropathy: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trialPain199983859010506675

- SinghGGastrointestinal Complications of Prescription and Over-the-Counter Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: A View from the ARAMIS DatabaseAm J Therap200071152111319579

- SorgeJStadlerThComparison of the analgesic efficacy and tolerability of tramadol 100 mg sustained-release tablets and tramadol 50 mg capsules for the treatment of chronic low back painClin Drug Invest19971415764

- TannenbaumHBombardierCDavisPAn evidence-based approach to prescribing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Third Canadian Consensus Conference GroupJ Rheumatol2006331405716331802

- VickersMDO’FlahertyDSzekelySMTramadol: pain relief by an opioid without depression of respirationAnaesthesia19924729161519677

- WheltonARenal and related cardiovascular effects of conventional and Cox-2-Specific NSAIDs and non-NSAID analgesicsAm J Therap20007637411319575

- Wilder-SmithCHHillLSpargoKTreatment of severe pain from osteoarthritis with slow-release tramadol or dihydrocodeine in combination with NSAIDs: a randomised study comparing analgesia, antinociception and gastrointestinal effectsPain200191233111240075

- ZhangWDohertyMArdenNEULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis – report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT)Ann Rheum Dis2005646698115471891