Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, defined as the presence of macrovascular steatosis in the presence of less than 20 gm of alcohol ingestion per day, is the most common liver disease in the USA. It is most commonly associated with insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. It is manifested by steatosis, steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and, rarely, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatic steatosis results from an imbalance between the uptake of fat and its oxidation and export. Insulin resistance, predisposing to lipolysis of peripheral fat with mobilization to and uptake of fatty acids by the liver, is the most consistent underlying pathogenic factor. It is not known why some patients progress to cirrhosis; however, the induction of CYP 2E1 with generation of reactive oxygen species appears to be important.

Treatment is directed at weight loss plus pharmacologic therapy targeted toward insulin resistance or dyslipidemia. Bariatric surgery has proved effective. While no pharmacologic therapy has been approved, emerging data on thiazolidinediones have demonstrated improvement in both liver enzymes and histology. There are fewer, but promising data, with statins which have been shown to be hepatoprotective in other liver diseases. The initial enthusiasm for ursodeoxycholic acid has not been supported by histologic studies.

Keywords:

Introduction

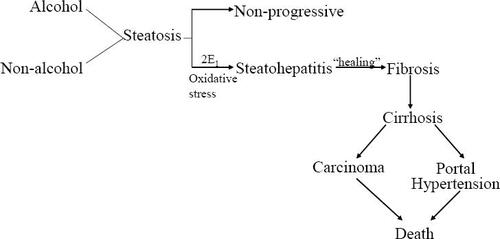

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined by the presence of hepatic macrovesicular steatosis in the presence of less than 20 g of alcohol ingestion per day. It is the most common liver disease in the US (CitationClark et al 2002; CitationBrowning et al 2004; CitationMcCullough 2005) and refers to a broad spectrum of liver disease which varies from bland steatosis (NAFLD) to steatohepatitis (NASH) to progressive fibrosis and, ultimately, cirrhosis with portal hypertension (CitationSilverman et al 1989; CitationPowell et al 1990; CitationMatteoni et al 1999; CitationMarchesini et al 2003). Hepatocellular carcinoma has been reported in those with cirrhosis (CitationBugianesi et al 2002; CitationCaldwell et al 2004).

Epidemiology and natural history

NAFLD was largely unknown prior to 1980 but is now recognized as the most common chronic liver disease in the US and many other parts of the world. The prevalence of NAFLD, as determined by population studies using ultrasound and serum enzymes, is estimated at 23%–30% (CitationClark et al 2002). The prevalence is expected to increase as the incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus increases. While such studies do not distinguish NASH, the progressive form of the disease, from bland steatosis, it has been suggested that the prevalence of NASH is 5.7%–17% of the general population (CitationMcCullough 2005).

NAFLD may lead to NASH, cirrhosis and in some cases, hepatocellular carcinoma (CitationPowell et al 1990; CitationMatteoni et al 1999; CitationBugianesi et al 2002). Fifty percent of patients with NAFLD have NASH and 19% have cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis (CitationSilverman et al 1989; CitationSilverman et al 1990; CitationMarchesini et al 2003). Once cirrhosis develops 30%–40% of patients will die of liver failure over a 10 year period (CitationMcCullough 2005), a rate that is at least equal to that seen with hepatitis C (CitationHui et al 2003). Hepatocellular carcinoma is an increasingly recognized outcome (CitationPowell et al 1990; CitationBugianesi et al 2002). Why some patients develop progressive disease while most do not remains to be determined, although genetic factors may be involved (CitationStruben et al 2000; CitationWillner et al 2001).

Etiology

The precise etiology of NAFLD is unknown but there is a strong association with obesity, the metabolic/insulin resistance syndrome and dyslipidemia (). Most patients with NASH are obese and there is increasing evidence of an obesity epidemic in the US and elsewhere (CitationFlegal et al 1998; CitationCalle et al 1999; CitationLivingston 2000; CitationJames et al 2004). It is estimated that 70%–80% of obese subjects have NAFLD with 15%–20% having NASH (CitationBugianesi et al 2002). A recent study demonstrated that 88% of patients with NASH have the insulin resistance syndrome (CitationMarchesini et al 2003). Type 2 diabetes (DM2) is associated with NAFLD in 30%–80% of subjects (CitationSilverman et al 1989, Citation1990; CitationMarchesini et al 1999) and NAFLD is present in virtually 100% of patients with combined DM2 and obesity (CitationWanless and Lentz 1990).

Table 1 Causes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

In patients with diabetes, the standardized mortality ratio for cirrhosis (2.52) is greater than that for cardiovascular disease (1.34) (Citationde Marco et al 1999).

Dyslipidemia is present in 50%–60% of individuals with NAFLD. Hypercholesterolemia alone is associated with a 33% prevalence (CitationAssy et al 2000).

Pathogenesis

The pathologic sequence of events from steatosis (ie, the “first hit”), to steatohepatitis to cirrhosis is well established (CitationPowell et al 1990; CitationBacon et al 1994) (). However, fat, per se is not hepatotoxic (CitationTeli et al 1995; CitationDam-Larsen et al 2004; CitationAdams et al 2005). Why some patients progress and most do not is not known. It is now widely accepted that a “second hit” is necessary for NAFLD to progress to NASH and cirrhosis. What is common to virtually all patients with NAFLD is insulin resistance. It remains uncertain if this is a primary or secondary event to steatosis.

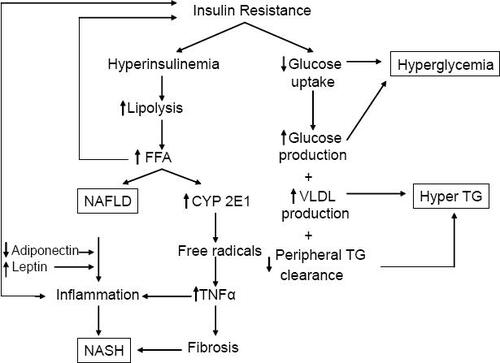

The presence of insulin resistance and/or obesity permits/promotes disease progression (CitationClark et al 2002; CitationBellentani et al 2004). They also seem to promote susceptibility to additive injury from alcohol (CitationYou and Crabb 2004) and hepatitis C (CitationPatel et al 2005). The clinical features which support progression are increasing age (>45 years), increasing BMI (>30), reversed ALT/AST ratio and elevated serum triglycerides (CitationAngulo et al 1999). The mechanisms remain somewhat speculative but a unifying concept of the pathophysiologic events is now evolving and these are pertinent as therapeutic targets ().

Figure 2 Unifying concept of the pathogenesis of NAFLD. ROS = reactive oxygen species, TG = triglycerides, VLDL = very low density lipoprotein, CYP = cytochrome P450.

Steatosis reflects a net retention of fat within hepatocytes and results from an imbalance between uptake of fat and its oxidation and export. The most consistent pathogenic factor is insulin resistance, leading to enhanced lipolysis which in turn increases circulating free fatty acids and their uptake by the liver (CitationMarchesini et al 1999). Fat accumulating in the liver has several effects: (1) upregulation of apoptosis (CitationFeldstein et al 2003a, Citation2003b), (2) indirect upregulation of TNFα which is pro-steatotic and pro-inflammatory (CitationDiehl 2004; CitationYou and Crabb 2004), (3) mitochondrial dysfunction (CitationPerez-Carreras et al 2003; CitationFeldstein et al 2004; CitationKharroubi et al 2004; CitationBegriche et al 2006) presumably increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and provoking lipid peroxidation of cell membranes, (4) induction of CYP 2E1 which generates ROS (CitationWeltman et al 1998; CitationNieto et al 2002; CitationChalasani et al 2003), (5) induction of pro-inflammatory genes such as TNFα (CitationSamuel et al 2004; CitationArkan et al 2005; CitationCai et al 2005), and COX2 which induce additional inflammatory mediators which are also pro-fibrotic (CitationNieto et al 2000). The net effect of the above is apoptosis, necroinflammation and fibrosis.

Hepatic fibrosis is promoted by steatosis even in the absence of liver cell injury (CitationReeves et al 1996). Adipokines, hormones secreted by adipocytes, appear to be important regulators of hepatic fibrosis. Leptin, which is increased in the metabolic syndrome, promotes fibrosis and induces pro-inflammatory cytokines (CitationSaxena et al 2002, Citation2004; CitationAleffi et al 2005) while adiponectin, which is decreased in metabolic syndrome, inhibits stellate cell activation. The net affect of increased leptin and decreased adiponectin is pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic. Finally, activation of the renin-angiotensin system is a characteristic feature of the metabolic syndrome (CitationPrasad and Quyyumi 2004). Angiotensin II, the most active mediator of this system, activates hepatic stellate cells and active collagen synthesis (CitationBataller, Gabele et al 2003; CitationBataller, Schwabe et al 2003; CitationBataller et al 2005).

Taken together these observations account for the characteristic histologic features of NASH (steatosis, apoptosis, inflammation and fibrosis) and provide important targets for therapy. A unifying concept of the pathophysiology is shown in . In summary, insulin resistance leads to hyper-insulinemia which in turn leads to lipolysis of peripheral fat with mobilization of fatty acids to the liver. The fatty acids are substrate for ß-oxidation as an energy source. In some patients, ie, those with NASH, reactive species are formed leading to oxidative stress with cell damage, inflammation and fibrosis.

Diagnosis

Most patients with NAFLD/NASH are asymptomatic or have only mild fatigue or slight right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort. The diagnosis should be suspected in anyone with the conditions listed in . The goals of evaluation are threefold: (1) establish a diagnosis of NAFLD, (2) determine the etiology, and (3) determine if there is progressive disease (ie, NASH). The gold standard for establishing a diagnosis of NAFLD and distinguishing it from NASH is the liver biopsy. A number of histologic scoring systems have been developed although none have been universally accepted (CitationKleiner et al 2005; CitationMendler et al 2005) (). The Pathology Committee of the NASH Clinical Research Network has devised a system derived from multiple logistic regressions and scored as the unweighted sum of scores of steatosis (0–3), lobular inflammation (0–3) and ballooning (0–2). NASH is defined as a score of ≥5 (CitationKleiner et al 2005). Another scoring system includes scores for fatty change (1–4), portal fibrosis (0–6) and activity comprising lobular inflammation (0–3), Mallory bodies (0–3), hepatocyte ballooning (0–3) and perisinusoidal fibrosis (0–3) (CitationMendler et al 2005). The latter system has the advantage of scoring fibrosis. All scoring systems are compromised by sampling error with a discordance rate of 18% in one study (CitationRatziu et al 2005). Furthermore, it is not possible to distinguish alcoholic from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease on histologic grounds and the distinction continues to be made by clinical criteria ie, less than or greater than 20 gms of alcohol per day. Liver biopsy is costly, invasive, and subject to sampling error. The search for non-invasive techniques continues.

Table 2 Types of NAFLD by histology and outcome

Ultrasound has an overall sensitivity of 89% with 93% specificity (CitationJoseph et al 1991) but falls off greatly in those with mild disease or fibrotic disease when the amount of fat in the liver is less than 30% (CitationSiegelman and Rosen 2001; CitationNeuschwander-Tetri and Caldwell 2003). The characteristic ultrasonic feature is the “bright” liver with increased parenchymal echo texture and vascular blurring. Areas of focal sparring can give the appearance of metastases (CitationMitchell 1992). The positive and negative predictive value of ultrasound in patients with abnormal liver chemistries and other causes of liver disease ruled out is 96% and 19% respectively. The value of ultrasound as a screening test has not been established and, given its low negative predictive value, it seems unlikely that it will be. Ultrasound is further compromised by an inability to detect fibrosis (CitationSaadeh et al 2002; CitationNeuschwander-Tetri and Caldwell 2003). Non-invasive methods for detecting fibrosis have not yet surfaced for routine clinical use.

Factors which are predictive of fibrotic disease are reversed ALT/AST ratio, hypoalbuminemia, elevated pro-thrombin time and thrombocytopenia (CitationAngulo et al 1999; CitationSorbi et al 1999). Clinical features such as ascites, esophageal varices, coagulopathy and encephalopathy are consistent with cirrhosis. Biopsy in such patients is not helpful and does not distinguish cirrhosis from other causes.

The search for etiology should include a serum lipid panel, a test for insulin resistance and a history of potential drug causes.

Treatment

Treatment falls into two categories: targeting either the steatosis or the pathogenesis of progression. There are no FDA approved pharmacologic agents and, in fact, no FDA guidelines for such drugs despite the fact that NAFLD is the most common liver disease in the US. The treatments used to date are outlined in . Virtually all are compromised by small numbers and lack of placebo control.

Table 3 Summary of interventions in NAFLD

Treatment of steatosis/insulin resistance

The treatment of steatosis is inexorably linked to obesity, insulin resistance and dyslipidemia. In general, factors that decrease steatosis consist of weight loss or pharmacologic therapy directed at insulin resistance or dyslipidemia. The treatment of steatohepatitis is directed at oxidative stress, inflammation and fibrosis. Factors that decrease oxidative stress and inflammation include antioxidants, probiotics, anti-cytokines and glutathione precursors. Anti-fibrotic therapy is in its infancy.

Weight loss

Weight loss improves liver chemistries, steatosis, necroinflammatory changes and fibrosis (CitationHuang et al 2005; CitationPetersen et al 2005; CitationSuzuki et al 2005). Furthermore, gradual weight reduction has been shown to lower insulin levels and improve quality of life (CitationPetersen et al 2005). Weight loss may be achieved through diet and exercise or bariatric surgery.

Diet

The ideal diet and rate of weight loss is yet to be determined although it is known that rapid weight loss may exacerbate disease (CitationAndersen et al 1991). A number of studies, both controlled and uncontrolled, indicate that weight loss decreases hepatic steatosis (CitationHuang et al 2005; CitationPetersen et al 2005; CitationSuzuki et al 2005). The durability of weight loss on hepatic steatosis remains to be determined. Low fat diets should be avoided (CitationSolga et al 2004; CitationKang et al 2006). Some have suggested that a Mediterranean diet (ie, high consumption of complex carbohydrates and monounsaturated fat, low amounts of red meat, and low/moderate amounts of wine) is preferred (CitationMusso et al 2003; CitationEsposito et al 2004). A low glycemic, low calorie diet with a weight loss of 1–2 kg/wk seems reasonable.

Bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery, recently reviewed by CitationAngulo (2006) has proved successful in a number of studies (CitationDixon et al 2004; CitationClark et al 2005; CitationMattar et al 2005; CitationBarker et al 2006; CitationKlein et al 2006; CitationMathurin et al 2006) The formerly used ileal bypass surgery was, however, associated with fatty liver and even hepatic failure (CitationMarubbio et al 1976). The durability of bariatric surgery has yet to be determined but it seems likely to be the only therapy that will change the natural history of NASH (CitationAngulo 2006).

Orlistat

Orlistat is a lipase inhibitor that promotes weight loss by reduction of fat absorption. A trial by CitationHarrison et al (2004) in 10 patients reported a mean weight loss of 10 kg with 6 months of treatment. Aminotransferases improved during treatment. No change in histology was reported. Another double blind, placebo-controlled trial by CitationZelber-Sagi et al (2006) randomized 52 patients with NAFLD (diagnosed by ultrasound and confirmed with biopsy) to orlistat or placebo for 6 months. Orlistat decreased aminotransferase levels and reversed fatty liver as determined by ultrasound. Similar results were seen in another open label trial of 12 nonrandomized, obese patients with NASH (CitationSabuncu et al 2003), although alkaline phosphatase levels increased during therapy. Orlistat has recently become available over the counter in the US. The side effects of gas, bloating and steatorrhea are problematic.

Sibutramine

Sibutramine, an appetite suppressant, is a serotonin reuptake antagonist approved for weight loss. It also has been studied in patients with NAFLD. It significantly improved aminotransferases in 13 of 13 patients and decreased evidence of hepatic steatosis on ultrasound in 11 of 13 patients in an open label, nonrandomized study (CitationSabuncu et al 2003). These patients were all obese and were diagnosed with NASH. Alkaline phosphatase levels increased during therapy.

Pharmacologic therapy

Thiazolidinediones

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are PPARγ agonists which increase insulin sensitivity and increase the number and activation of adipocytes (CitationShulman 2000). This leads to a redistribution of lipids from liver and muscle cells to adipocytes which, in turn, restores insulin sensitivity (CitationShulman 2000; CitationBajaj et al 2004). They also increase adiponectin expression, decrease TNFα expression, (CitationIwata et al 2001; CitationHernandez et al 2004) and reduce collagen synthesis (CitationGalli et al 2002). The net effect of PPARγ agonists is an increase in insulin sensitivity, a redistribution of fat from liver to adipocytes and a reduction in hepatic fibrosis. Animal studies have confirmed these observations (CitationJia et al 2000; CitationGalli et al 2002) and human trials are beginning to confirm the beneficial effects (CitationCaldwell et al 2001). In the initial study using troglitazone, 7 of 10 patients showed improvement in ALT after 6 months. There was, however, no histologic improvement and troglitazone was removed from the market because of hepatotoxicity. Subsequent trials with pioglitazone and rosiglitazone have not shown evidence of hepatotoxicity.

Pioglitazone

Three small trials and a large controlled trial have evaluated pioglitazone in the treatment of NAFLD (CitationShadid and Jensen 2003; CitationPromrat et al 2004; CitationSanyal et al 2004; CitationBelfort et al 2006). A 48 week trial of pioglitazone, 30 mg daily, in 18 patients by CitationPromrat et al (2004) showed improvement in ALT and histology. Fibrosis decreased in 61% and remained stable in 22%. A 6 month controlled trial by CitationSanyal et al (2004) of 20 patients compared vitamin E (400 I.U./d) to pioglitazone (30mg/day) plus vitamin E. The combination showed improvement in insulin sensitivity and histology.

In the largest controlled trial to date with pioglitazone, Belfort et al compared diet plus pioglitazone to diet plus placebo in 55 patients (CitationBelfort et al 2006). The pioglitazone group showed significant improvement in ALT (by 58%), hepatic fat content (by 54%) and insulin sensitivity (by 48%). There was significant histologic improvement in steatosis, ballooning necrosis and inflammation but not fibrosis.

Rosiglitazone

There have been 3 trials, including a placebo controlled trial, with rosiglitazone (CitationNeuschwander-Tetri et al 2003; CitationTiikkainen et al 2004; CitationRatziu et al 2006). In the first of these studies (CitationNeuschwander-Tetri et al 2003), 30 patients were treated with rosiglitazone 8mg daily for 48 weeks. There was significant improvement in ALT, AST, GGT and insulin sensitivity. Of the 22 patients who had histologic evaluation, steatosis improved in 13 and worsened in one; fibrosis score improved in 8 and worsened in 3. This study was confounded by the use of statins. The results of the 63 patient, French multicenter placebo controlled trial known as FLIRT have just been presented (CitationRatziu et al 2006). There was improvement in histology (47%) compared to placebo (16%) and ALT (38%) versus placebo (7%). Interestingly, the non-diabetic patients did better than the diabetic patients in this study.

In summary, several trials have shown a beneficial effect of TZDs in patients with insulin resistance syndrome/DM2. Issues about hepatotoxicity have been dispelled (CitationTolman and Chandramouli 2003) and there is evidence that the use of TZDs in patients with elevated baseline liver chemistries is safe (CitationChalasani et al 2005). It is yet to be determined if there are long-term benefits. However, there has been consistent short-term benefit in surrogate (serum ALT) and histologic markers. TZDs, despite their shortcomings, are emerging as the drugs of choice for treating diabetic patients with NASH. However, as recently stated by CitationMcCullough (2006), the best description of TZDs for NASH may be, “Promising but not ready for prime time”.

Metformin

Metformin is a biguanide that stimulates ß-oxidation in the mitochondria (CitationDeFronzo et al 1991). It also suppresses lipogenic enzymes. In so doing it bypasses insulin resistance by utilizing fatty acids as an energy source. It is in this way that it reduces hyperinsulinemia (CitationStumvoll et al 1995; CitationCusi et al 1996). Animal studies in ob/ob mice with fatty liver disease have shown improvement in steatosis and aminotransferase abnormalities (CitationLin et al 2000). Human trials have been less convincing. Three small trails resulted in a significant reduction in aminotransferase levels (CitationMarchesini et al 2001; CitationUygun et al 2004; CitationSchwimmer et al 2005). One of the trials showed enhanced insulin sensitivity and a transient improvement in serum aminotransferase levels (CitationMarchesini et al 2001). In another trial, metformin and diet were compared to diet alone over 6 months. A statistically significant reduction in ALT, insulin and C-peptide was detected. There was also an improvement in necroinflammation that did not reach statistical significance (CitationUygun et al 2004). The increase in anaerobic respiration and potential for lactic acidosis is more a theoretical than actual concern except in patients with alcoholism and underlying renal insufficiency. Long term benefits and histologic benefit have not been demonstrated. At the present time, metformin cannot be recommended for non-diabetic patients with NASH.

Statins

Statins are currently used to treat NAFLD (CitationHorlander et al 2001; CitationKiyici et al 2003; CitationRallidis et al 2004; CitationAntonopoulos et al 2006). Recent studies suggest that statins are hepatoprotective in patients with other forms of liver disease including hepatitis C (CitationChalasani et al 2004). Statins may reduce hepatic fat content in patients with hyperlipidemia and NASH (CitationHorlander et al 2001; CitationKiyici et al 2003). To date, atorvastatin, pravastatin, and rosuvastatin have been studied. An important point about these studies is that the statin doses were not equipotent nor comparable in their lipid lowering effect.

Atorvastatin was compared with ursodeoxycholic acid in a small trial of 44 obese adults with NASH, including 10 patients with diabetes (CitationKiyici et al 2003). In the statin arm of the study, hyperlipidemic patients received atorvastatin 10 mg daily for 6 months. Liver chemistries improved and an increase in liver density, suggesting a decrease in fat content, occurred in the atorvastatin group.

Two other statins have been evaluated in patients with NAFLD. Pravastatin, at a dose of 20 mg daily for 6 months, normalized liver enzymes and improved hepatic inflammation in 5 of 5 patients (CitationRallidis et al 2004). Rosuvastatin was studied in 23 patients with hyperlipidemia and biochemical and ultrasound evidence of NAFLD (CitationAntonopoulos et al 2006). After 8 months of rosuvastatin 10 mg daily, all patients had normal ALT and AST and all achieved LDL goals. Histology was not evaluated. In summary, further studies are needed but statins are promising agents for the treatment of NASH as well as other liver diseases.

Fibric acid derivatives

Gemfibrozil, 600 mg daily for 1 month, has been studied in a randomized, controlled study of 46 patients with NAFLD. The ALT normalized over this period, but histologic changes were not evaluated (CitationBasaranoglu, Acbay et al 1999). The dose of gemfibrozil in this trial was less than the labeled dose of 1200 mg per day.

Treatment of pathophysiologic mechanisms

There is increasing interest in treating NASH by targeting the pathophysiologic mechanisms.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is an important mechanism of cell death in NAFLD.

Ursodeoxycholic acid

Ursodiol (ursodeoxycholic acid) is an anti-apoptotic, cyto-protective, immune-modulating, anti-inflammatory agent that is widely used in liver disease. The results of initial studies varied, but some showed promising results in improving ALT (CitationLaurin et al 1996; CitationKiyici et al 2003) while others reported no significant difference in ALT (CitationVajro et al 2000; CitationLindor et al 2004). In one of the studies, ursodiol did show improvement in steatosis, but no improvement in inflammation or fibrosis (CitationLaurin et al 1996). All of these studies were small (17 to 24 patients) and had no comparator group. To further study ursodiol, a randomized, placebo controlled trial involving 166 patients with NASH compared ursodiol to placebo for 2 years (CitationLindor et al 2004). Liver function tests improved in both groups; however, significant differences were not detected between placebo and ursodiol. Histologic changes (steatosis, necroinflammation, or fibrosis) also were not significantly different between the ursodiol and placebo groups. At the present time, ursodiol cannot be recommended. Studies are underway using it as add-on therapy.

Oxidative stress/inflammation

Antioxidants

Oxidative stress is important in the pathogenesis of NASH, and antioxidants (vitamin E) may decrease levels of profibrinogenic TGF-β, improve histology, and inhibit hepatic stellate cell activation.

Vitamin E/vitamin C

Pilot studies with vitamin E have been conducted (CitationLavine 2000; CitationHasegawa et al 2001; CitationHarrison et al 2003; CitationSanyal et al 2004; CitationBugianesi et al 2005) with promising results in reducing aminotransferases. One randomized placebo controlled trial looked at the combination of vitamin E and vitamin C (CitationHarrison et al 2003). Improvement in hepatic inflammation and fibrosis was detected. However, these differences were not significantly different from the placebo arm. A recent open label study compared vitamin E to metformin and weight loss (CitationBugianesi et al 2005). Vitamin E was inferior to metformin and/or weight loss in improving aminotransferases.

A recent meta-analysis of high dose vitamin E in the general population revealed an increase in overall mortality (CitationMiller et al 2005). Due to the possible increase in mortality with general use of antioxidants and the mixed results from clinical trials in NASH, the use of antioxidants is not recommended.

Pro-biotics/pre-biotics

Probiotics may reduce hepatic injury in animal models where intestinal derived bacterial endotoxin sensitizes fatty livers to the effects of TNF-α. A 3-month treatment period of a commercially available probiotic, VSL #3, given to 22 patients with NAFLD did improve ALT levels and markers of lipid peroxidation (CitationLoguercio et al 2005). Histology was not evaluated in this trial.

Anti-cytokines

Pentoxifylline

TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that triggers the production of additional cytokines that recruit inflammatory cells and leads to the destruction of hepatocytes and induction of fibrogenesis. This cytokine is increased in NASH. Pentoxifyl-line is a methylxanthine compound that inhibits TNF-α and is a promising agent in the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis. A pilot study in 20 cpatients detected improvement in liver enzymes in patients with NASH (CitationAdams et al 2004). However, the high incidence of gastrointestinal side effects led to early withdrawal in many patients. CitationSatapathy et al (2004) found that pentoxifylline reduced mean transaminase levels, reduced serum TNF-α levels, and improved insulin resistance in 18 patients over a 6 month period. Another trial by CitationLee et al (2006) studied 20 patients with NASH and randomized them to 3 months of pentoxifylline or placebo. Both groups had significant decreases in BMI and aminotransferase levels, but there were no significant differences between groups. More patients who received pentoxifylline achieved normal AST. Both groups reported a significant decrease in TNF-α, Il-6, Il-8, and serum hyaluronic acid.

Glutathione precursors

Betaine

Betaine is a component of the metabolic cycle of thionine and may increase S-adenosylmethionine levels. This process may protect against steatosis in alcoholic liver disease animal models. A small, 1-year trial showed that betaine significantly improved aminotransferase levels versus baseline (CitationAbdelmalek et al 2001). In addition, a marked improvement in the degree of steatosis, necroinflammatory grade, and stage of fibrosis was observed. CitationAbdelmalek et al (2006) then conducted a placebo-controlled, 12-month trial of 55 patients and reported that betaine did not significantly improve aminotransferases or liver histology.

Fibrosis

Animal studies have shown that angiotensin II promotes insulin resistance and hepatic fibrosis.

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists

Lorsartan

Losartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, has been used in two studies (CitationYokohama et al 2004, Citation2006). In an historically controlled study (CitationYokohama et al 2004, Citation2006), losartan 50 mg daily was associated with improved aminotransferases, serum markers of fibrosis, and plasma TGF-β1. Histological improvements were detected in several of the patients: necroinflammation (5 patients), reduction of hepatic fibrosis (4 patients), and reduced iron disposition (2 patients).

Summary

There is increasing understanding of the risk factors for NAFLD and its underlying pathophysiology. New therapies are evolving but weight loss remains the mainstay of therapy. Targeted pharmacologic therapy is evolving in the treatment of the underlying pathophysiologic events of steatosis, apoptosis, oxidative stress and fibrosis. The thiazolidinediones, have shown promising results in the reduction of steatosis and, perhaps, the progression to cirrhosis. However, further controlled clinical trials are needed before any specific therapy other than weight loss and exercise can be recommended without reservation. Patients with insulin resistance can be treated with thiazolidinediones while patients with dyslipidemia can be treated with lipid lowering agents.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Tolman serves on the ACTOS Drug Safety Monitoring Board for Takeda Pharmaceuticals and is on the Speakers Bureau of Eli Lilly and Company.

References

- AbdelmalekMFAnguloPBetaine, a promising new agent for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: results of a pilot studyAm J Gastroenterol20019627111711569700

- AbdelmalekMFSandersonSOBetaine for treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. AASLD, October, 2006. Final ID:33Hepatology200644Suppl 1200A

- AdamsLALympJFThe natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort studyGastroenterology20051291132116012941

- AdamsLAZeinCOA pilot trial of pentoxifylline in nonalcoholic steatohepatitisAm J Gastroenterol2004992365815571584

- AleffiSPetraiIUpregulation of proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines by leptin in human hepatic stellate cellsHepatology20054213394816317688

- AndersenTGluudCHepatic effects of dietary weight loss in morbidly obese subjectsJ Hepatol19911222492051001

- AnguloPNAFLD, obesity, and bariatric surgeryGastroenterology200613018485216697746

- AnguloPKeachJCIndependent predictors of liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisHepatology19993013566210573511

- AntonopoulosSMikrosSRosuvastatin as a novel treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in hyperlipidemic patientsAtherosclerosis2006184233416168995

- ArkanMCHevenerALIKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistanceNat Med200511191815685170

- AssyNKaitaKFatty infiltration of liver in hyperlipidemic patientsDig Dis Sci20004519293411117562

- BaconBRFarahvashMJNonalcoholic steatohepatitis: an expanded clinical entityGastroenterology1994107110397523217

- BajajMSuraamornkulSDecreased plasma adiponectin concentrations are closely related to hepatic fat content and hepatic insulin resistance in pioglitazone-treated type 2 diabetic patientsJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200489200614715850

- BarkerKBPalekarNANon-alcoholic steatohepatitis: effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgeryAm J Gastroenterol20061013687316454845

- BasaranogluMAcbayOA controlled trial of gemfibrozil in the treatment of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisJ Hepatol199931384

- BatallerRGabeleEProlonged infusion of angiotensin II into normal rats induces stellate cell activation and proinflammatory events in liverAm J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol2003285G6425112773299

- BatallerRSancho-BruPLiver fibrogenesis: a new role for the renin-angiotensin systemAntioxid Redox Signal2005713465516115040

- BatallerRSchwabeRFNADPH oxidase signal transduces angiotensin II in hepatic stellate cells and is critical in hepatic fibrosisJ Clin Invest200311213839414597764

- BegricheKIgoudjilAMitochondrial dysfunction in NASH: causes, consequences and possible means to prevent itMitochondrion2006612816406828

- BelfortRHarrisonSAA placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisN Engl J Med2006355229730717135584

- BellentaniSBedogniGThe epidemiology of fatty liverEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol20041610879315489565

- BrowningJDSzczepaniakLSPrevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicityHepatology20044013879515565570

- BugianesiEGentilcoreEA randomized controlled trial of metformin versus vitamin E or prescriptive diet in nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseAm J Gastroenterol200510010829015842582

- BugianesiELeoneNExpanding the natural history of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: from cryptogenic cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinomaGastroenterology20021231344012105842

- CaiDYuanMLocal and systemic insulin resistance resulting from hepatic activation of IKK-beta and NF-kappaBNat Med2005111839015685173

- CaldwellSHCrespoDMObesity and hepatocellular carcinomaGastroenterology2004127S9710315508109

- CaldwellSHHespenheideEEA pilot study of a thiazolidinedione, troglitazone, in nonalcoholic steatohepatitisAm J Gastroenterol2001965192511232700

- CalleEEThunMJBody-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adultsN Engl J Med1999341109710510511607

- ChalasaniNAljadheyHPatients with elevated liver enzymes are not at higher risk for statin hepatotoxicityGastroenterology200412612879215131789

- ChalasaniNGorskiJCHepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 activity in nondiabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisHepatology2003375445012601351

- ChalasaniNTealEEffect of rosiglitazone on serum liver biochemistries in diabetic patients with normal and elevated baseline liver enzymesAm J Gastroenterol200510013172115929763

- ClarkJMAlkhuraishiARRoux-en-Y gastric bypass improves liver histology in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver diseaseObes Res2005131180616076987

- ClarkJMBrancatiFLNonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseGastroenterology200212216495712016429

- CusiKConsoliAMetabolic effects of metformin on glucose and lactate metabolism in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitusJ Clin Endocrinol Metab1996814059678923861

- Dam-LarsenSFranzmannMLong term prognosis of fatty liver: risk of chronic liver disease and deathGut200453750515082596

- de MarcoRLocatelliFCause-specific mortality in type 2 diabetes. The Verona Diabetes StudyDiabetes Care1999227566110332677

- DeFronzoRABarzilaiNMechanism of metformin action in obese and lean noninsulin-dependent diabetic subjectsJ Clin Endocrinol Metab19917312943011955512

- DiehlAMTumor necrosis factor and its potential role in insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseClin Liver Dis2004861938x15331067

- DixonJBBhathalPSNonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Improvement in liver histological analysis with weight lossHepatology20043916475415185306

- EspositoKMarfellaREffect of a mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trialJAMA20042921440615383514

- FeldsteinAECanbayAHepatocyte apoptosis and fas expression are prominent features of human nonalcoholic steatohepatitisGastroenterology2003a1254374312891546

- FeldsteinAECanbayADiet associated hepatic steatosis sensitizes to Fas mediated liver injury in miceJ Hepatol2003b399788314642615

- FeldsteinAEWerneburgNWFree fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-alpha expression via a lysosomal pathwayHepatology2004401859415239102

- FlegalKMCarrollMDOverweight and obesity in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1960–1994Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord19982239479481598

- GalliACrabbDWAntidiabetic thiazolidinediones inhibit collagen synthesis and hepatic stellate cell activation in vivo and in vitroGastroenterology200212219244012055599

- HarrisonSAFinckeCA pilot study of orlistat treatment in obese, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis patientsAliment Pharmacol Ther200420623815352910

- HarrisonSATorgersonSVitamin E and vitamin C treatment improves fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisAm J Gastroenterol20039824859014638353

- HasegawaTYonedaMPlasma transforming growth factor-beta1 level and efficacy of alpha-tocopherol in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot studyAliment Pharmacol Ther20011516677211564008

- HernandezRTeruelTRosiglitazone ameliorates insulin resistance in brown adipocytes of Wistar rats by impairing TNF-alpha induction of p38 and p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinasesDiabetologia20044716152415365619

- HorlanderJKwoPAtorvastatin for the treatment of NASHGastroenterology20015A-5442767 abstract

- HuangMAGreensonJKOne-year intense nutritional counseling results in histological improvement in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot studyAm J Gastroenterol200510010728115842581

- HuiJMKenchJGLong-term outcomes of cirrhosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis compared with hepatitis CHepatology200338420712883486

- IwataMHarutaTPioglitazone ameliorates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced insulin resistance by a mechanism independent of adipogenic activity of peroxisome proliferator – activated receptor-gammaDiabetes20015010839211334412

- JamesPTRigbyNThe obesity epidemic, metabolic syndrome and future prevention strategiesEur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil2004113815167200

- JiaDMTabaruATroglitazone prevents fatty changes of the liver in obese diabetic ratsJ Gastroenterol Hepatol20001511839111106100

- JosephAESaverymuttuSHComparison of liver histology with ultrasonography in assessing diffuse parenchymal liver diseaseClin Radiol19914326311999069

- KangHGreensonJKMetabolic syndrome is associated with greater histologic severity, higher carbohydrate, and lower fat diet in patients with NAFLDAm J Gastroenterol200610122475317032189

- KharroubiILadriereLFree fatty acids and cytokines induce pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis by different mechanisms: role of nuclear factor-kappaB and endoplasmic reticulum stressEndocrinology200414550879615297438

- KiyiciMGultenMUrsodeoxycholic acid and atorvastatin in the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitisCan J Gastroenterol2003177131814679419

- KleinSMittendorferBGastric bypass surgery improves metabolic and hepatic abnormalities associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseGastroenterology200613015647216697719

- KleinerDEBruntEMDesign and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseHepatology20054131321

- LaurinJLindorKDUrsodeoxycholic acid or clofibrate in the treatment of non-alcohol-induced steatohepatitis: a pilot studyHepatology199623146478675165

- LavineJEVitamin E treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children: a pilot studyJ Pediatr2000136734810839868

- LeeYSutedjaDA randomized controlled double blind study of pentoxifylline in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)Hepatology200644Suppl 1654A

- LinHZYangSQMetformin reverses fatty liver disease in obese, leptin-deficient miceNat Med20006998100310973319

- LindorKDKowdleyKVUrsodeoxycholic acid for treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: results of a randomized trialHepatology200439770814999696

- LivingstonBEpidemiology of childhood obesity in EuropeEur J Pediatr2000159Suppl 1S143411011953

- LoguercioCFedericoABeneficial effects of a probiotic VSL#3 on parameters of liver dysfunction in chronic liver diseasesJ Clin Gastroenterol200539540315942443

- MarchesiniGBriziMMetformin in non-alcoholic steatohepatitisLancet2001358893411567710

- MarchesiniGBriziMAssociation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistanceAm J Med1999107450510569299

- MarchesiniGBugianesiENonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndromeHepatology2003379172312668987

- MarubbioATJrBuchwaldHHepatic lesions of central peri-cellular fibrosis in morbid obesity, and after jejunoileal bypassAm J Clin Pathol19766668491970370

- MathurinPGonzalezFThe evolution of severe steatosis after bariatric surgery is related to insulin resistanceGastroenterology200613016172416697725

- MattarSGVelcuLMSurgically-induced weight loss significantly improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndromeAnn Surg200524261017 discussion 618–2016192822

- MatteoniCAYounossiZMNonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severityGastroenterology199911614131910348825

- McCulloughAJFarrellGCGeorgeJHallPThe epidemiology and risk factors of NASHFatty liver disease: NASH and related disorders2005OxfordBlackwell2337

- McCulloughAJThiazolidinediones for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis – promising but not ready for prime timeN Engl J Med20063552361317135591

- MendlerMHKanelGProposal for a histological scoring and grading system for non-alcoholic fatty liver diseaseLiver Int20052529430415780053

- MillerER3rdPastor-BarriusoRMeta-analysis: high-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortalityAnn Intern Med2005142374615537682

- MitchellDGFocal manifestations of diffuse liver disease at MR imagingRadiology19921851111523289

- MussoGGambinoRDietary habits and their relations to insulin resistance and postprandial lipemia in nonalcoholic steatohepatitisHepatology20033749091612668986

- Neuschwander-TetriBABruntEMImproved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis after 48 weeks of treatment with the PPAR-gamma ligand rosiglitazoneHepatology20033810081714512888

- Neuschwander-TetriBACaldwellSHNonalcoholic steatohepatitis: summary of an AASLD Single Topic ConferenceHepatology20033712021912717402

- NietoNFriedmanSLCytochrome P450 2E1-derived reactive oxygen species mediate paracrine stimulation of collagen I protein synthesis by hepatic stellate cellsJ Biol Chem200227798536411782477

- NietoNGreenwelPEthanol and arachidonic acid increase alpha 2(I) collagen expression in rat hepatic stellate cells overexpressing cytochrome P450 2E1. Role of H2O2 and cyclooxygenase-2J Biol Chem2000275201364510770928

- PatelKZekryASteatosis and chronic hepatitis C virus infection: mechanisms and significanceClin Liver Dis20059399410vi16023973

- Perez-CarrerasMDel HoyoPDefective hepatic mitochondrial respiratory chain in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisHepatology200338999100714512887

- PetersenKFDufourSReversal of nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis, hepatic insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia by moderate weight reduction in patients with type 2 diabetesDiabetes200554603815734833

- PowellEECooksleyWGThe natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a follow-up study of forty-two patients for up to 21 yearsHepatology19901174802295475

- PrasadAQuyyumiAARenin-angiotensin system and angiotensin receptor blockers in the metabolic syndromeCirculation200411015071215364819

- PromratKLutchmanGA pilot study of pioglitazone treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitisHepatology2004391889614752837

- RallidisLSDrakoulisCKPravastatin in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: results of a pilot studyAtherosclerosis2004174193615135271

- RatziuVCharlotteFSampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseGastroenterology2005128189890615940625

- RatziuVCharlotteFA one year randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of rosiglitazone in non alcoholic steatohepatitis: results of the FLIRT pilot trialHepatology2006444 Suppl 1201A

- ReevesHLBurtADHepatic stellate cell activation occurs in the absence of hepatitis in alcoholic liver disease and correlates with the severity of steatosisJ Hepatol199625677838938545

- SaadehSYounossiZMThe utility of radiological imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseGastroenterology20021237455012198701

- SabuncuTNazligulYThe effects of sibutramine and orlistat on the ultrasonographic findings, insulin resistance and liver enzyme levels in obese patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitisRom J Gastroenterol2003121899214502318

- SamuelVTLiuZXMechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseaseJ Biol Chem2004279323455315166226

- SanyalAJMofradPSA pilot study of vitamin E versus vitamin E and pioglitazone for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2004211071515625656

- SatapathySKGargSBeneficial effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibition by pentoxifylline on clinical, biochemical, and metabolic parameters of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisAm J Gastroenterol20049919465215447754

- SaxenaNKIkedaKLeptin in hepatic fibrosis: evidence for increased collagen production in stellate cells and lean littermates of ob/ob miceHepatology2002357627111915021

- SaxenaNKTitusMALeptin as a novel profibrogenic cytokine in hepatic stellate cells: mitogenesis and inhibition of apoptosis mediated by extracellular regulated kinase (Erk) and Akt phosphorylationFaseb J20041816121415319373

- SchwimmerJBMiddletonMSA phase 2 clinical trial of metformin as a treatment for non-diabetic paediatric non-alcoholic steatohepatitisAliment Pharmacol Ther200521871915801922

- ShadidSJensenMDEffect of pioglitazone on biochemical indices of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in upper body obesityClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20031384715017657

- ShulmanGICellular mechanisms of insulin resistanceJ Clin Invest2000106171610903330

- SiegelmanESRosenMAImaging of hepatic steatosisSemin Liver Dis200121718011296698

- SilvermanJFO’BrienKFLiver pathology in morbidly obese patients with and without diabetesAm J Gastroenterol1990851349552220728

- SilvermanJFPoriesWJLiver pathology in diabetes mellitus and morbid obesity. Clinical, pathological, and biochemical considerationsPathol Annu198924Pt 12753022654841

- SolgaSAlkhuraisheARDietary composition and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseDig Dis Sci20044915788315573908

- SorbiDBoyntonJThe ratio of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase: potential value in differentiating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis from alcoholic liver diseaseAm J Gastroenterol19999410182210201476

- StrubenVMHespenheideEENonalcoholic steatohepatitis and cryptogenic cirrhosis within kindredsAm J Med200010891311059435

- StumvollMNurjhanNMetabolic effects of metformin in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitusN Engl J Med199533355047623903

- SuzukiALindorKEffect of changes on body weight and lifestyle in nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseJ Hepatol2005431060616140415

- TeliMRJamesOFThe natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver: a follow-up studyHepatology1995221714197489979

- TiikkainenMHakkinenAMEffects of rosiglitazone and met-formin on liver fat content, hepatic insulin resistance, insulin clearance, and gene expression in adipose tissue in patients with type 2 diabetesDiabetes20045321697615277403

- TolmanKGChandramouliJHepatotoxicity of the thiazolidinedionesClin Liver Dis2003736979vi12879989

- UygunAKadayifciAMetformin in the treatment of patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitisAliment Pharmacol Ther2004195374414987322

- VajroPFranzeseALack of efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of liver abnormalities in obese childrenJ Pediatr20001367394310839869

- WanlessIRLentzJSFatty liver hepatitis (steatohepatitis) and obesity: an autopsy study with analysis of risk factorsHepatology1990121106102227807

- WeltmanMDFarrellGCHepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 is increased in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisHepatology199827128339425928

- WillnerIRWatersBNinety patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: insulin resistance, familial tendency, and severity of diseaseAm J Gastroenterol20019629576111693332

- YokohamaSTokusashiYInhibitory effect of angiotensin II receptor antagonist on hepatic stellate cell activation in non-alcoholic steatohepatitisWorld J Gastroenterol200612322616482638

- YokohamaSYonedaMTherapeutic efficacy of an angiotensin II receptor antagonist in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitisHepatology2004401222515382153

- YouMCrabbDWRecent advances in alcoholic liver disease II. Minireview: molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liverAm J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol2004287G1615194557

- Zelber-SagiSKesslerAA double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of orlistat for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseClin Gastroenterol Hepatol200646394416630771