Abstract

Objective

To explore and evaluate the most common factors causing therapeutic non-compliance.

Methods

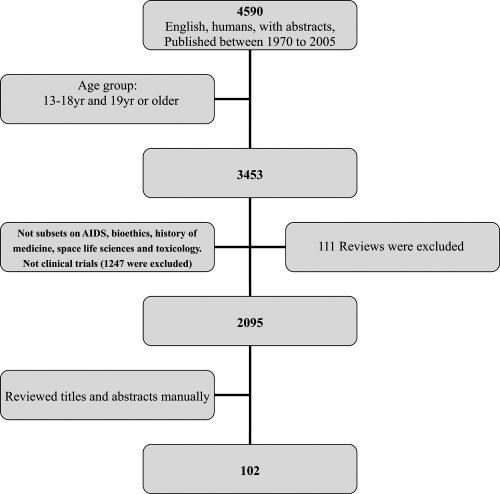

A qualitative review was undertaken by a literature search of the Medline database from 1970 to 2005 to identify studies evaluating the factors contributing to therapeutic non-compliance.

Results

A total of 102 articles was retrieved and used in the review from the 2095 articles identified by the literature review process. From the literature review, it would appear that the definition of therapeutic compliance is adequately resolved. The preliminary evaluation revealed a number of factors that contributed to therapeutic non-compliance. These factors could be categorized to patient-centered factors, therapy-related factors, social and economic factors, healthcare system factors, and disease factors. For some of these factors, the impact on compliance was not unequivocal, but for other factors, the impact was inconsistent and contradictory.

Conclusion

There are numerous studies on therapeutic noncompliance over the years. The factors related to compliance may be better categorized as “soft” and “hard” factors as the approach in countering their effects may differ. The review also highlights that the interaction of the various factors has not been studied systematically. Future studies need to address this interaction issue, as this may be crucial to reducing the level of non-compliance in general, and to enhancing the possibility of achieving the desired healthcare outcomes.

Keywords:

Introduction

The ultimate aim of any prescribed medical therapy is to achieve certain desired outcomes in the patients concerned. These desired outcomes are part and parcel of the objectives in the management of the diseases or conditions. However, despite all the best intention and efforts on the part of the healthcare professionals, those outcomes might not be achievable if the patients are non-compliant. This shortfall may also have serious and detrimental effects from the perspective of disease management. Hence, therapeutic compliance has been a topic of clinical concern since the 1970s due to the widespread nature of non-compliance with therapy. Therapeutic compliance not only includes patient compliance with medication but also with diet, exercise, or life style changes. In order to evaluate the possible impact of therapeutic non-compliance on clinical outcomes, numerous studies using various methods have been conducted in the United States (USA), United Kingdom (UK), Australia, Canada and other countries to evaluate the rate of therapeutic compliance in different diseases and different patient populations. Generally speaking, it was estimated that the compliance rate of long-term medication therapies was between 40% and 50%. The rate of compliance for short-term therapy was much higher at between 70% and 80%, while the compliance with lifestyle changes was the lowest at 20%–30% (CitationDiMatteo 1995). Furthermore, the rates of non-compliance with different types of treatment also differ greatly. Estimates showed that almost 50% of the prescription drugs for the prevention of bronchial asthma were not taken as prescribed (CitationSabaté 2003). Patients’ compliance with medication therapy for hypertension was reported to vary between 50% and 70% (CitationSabaté 2003). In one US study, Monane et al found that antihypertensive compliance averaged 49%, and only 23% of the patients had good compliance levels of 80% or higher (CitationMonane et al 1996). Among adolescent outpatients with cancer, the rate of compliance with medication was reported to be 41%, while among teenagers with cancer it was higher at between 41% and 53% (CitationTebbi et al 1986). For the management of diabetes, the rate of compliance among patients to diet varied from 25% to 65%, and for insulin administration was about 20% (CitationCerkoney and Hart 1980). More than 20 studies published in the past few years found that compliance with oral medication for type 2 diabetes mellitus ranged from 65% to 85% (CitationRubin 2005). As previously mentioned, if the patients do not follow or adhere to the treatment plan faithfully, the intended beneficial effects of even the most carefully and scientifically-based treatment plan will not be realized. The above examples illustrate the extent of the problem of therapeutic non-compliance and why it should be a concern to all healthcare providers.

Definition of compliance

To address the issue of therapeutic non-compliance, it is of first and foremost importance to have a clear and acceptable definition of compliance. In the Oxford dictionary, compliance is defined as the practice of obeying rules or requests made by people in authority (Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English). In healthcare, the most commonly used definition of compliance is “patient’s behaviors (in terms of taking medication, following diets, or executing life style changes) coincide with healthcare providers’ recommendations for health and medical advice” (CitationSackett 1976). Thus, therapeutic non-compliance occurs when an individual’s health-seeking or maintenance behavior lacks congruence with the recommendations as prescribed by a healthcare provider. Other similar terms have been used instead of compliance, and the meaning is more or less identical. For example, the term adherence is often used interchangeably with compliance. Adherence is defined as the ability and willingness to abide by a prescribed therapeutic regimen (CitationInkster 2006). Recently, the term “concordance” is also suggested to be used. Compared with “compliance”, the term concordance makes the patient the decision-maker in the process and denotes patients-prescribers agreement and harmony (CitationVermeire et al 2001). Although there are slight and subtle differences between these terms, in clinical practice, these terms are used interchangeably (albeit may not be totally correctly). Therefore, the more commonly used term of compliance will be used throughout this article.

Types of non-compliance

After defining what is meant by compliance, the next question that comes to mind to the healthcare providers would be: “What are the common types of non-compliance encountered in clinical medicine?” A knowledge and understanding of the various types of non-compliance commonly encountered in clinical practice would allow the formulation of strategies to tackle them effectively. A review of the literature reveals several types of commonly reported or detected non-compliance. () Besides the types of non-compliance encountered, another logical question to ask in trying to complete the jigsaw puzzle of therapeutic non-compliance would be: “In clinical medicine, what is considered to be good or acceptable compliance?” Although it must be acknowledged that this is still controversial, in relation to good medication compliance, it has commonly been defined as taking 80 to 120% of the medication prescribed (CitationSackett et al 1975; CitationMonane et al 1996; CitationAvorn et al 1998; CitationHope et al 2004). For compliance with other treatment such as exercise or diet, the definition of acceptable compliance varied among different studies and there does not seem to be any commonly accepted criterion to define good or acceptable compliance.

Table 1 Type of reported non-compliance

Problems with therapeutic non-compliance

Before we can formulate strategies to tackle the issue of therapeutic non-compliance, we need to assess the clinical and other implications of therapeutic non-compliance.

From the perspective of healthcare providers, therapeutic compliance is a major clinical issue for two reasons. Firstly, non-compliance could have a major effect on treatment outcomes and direct clinical consequences. Non-compliance is directly associated with poor treatment outcomes in patients with diabetes, epilepsy, AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), asthma, tuberculosis, hypertension, and organ transplants (CitationSabaté 2003). In hypertensive patients, poor compliance with therapy is the most important reason for poorly controlled blood pressure, thus increasing the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, and renal impairment markedly. Data from the third NHANES (the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey), which provides periodic information on the health of the US population, showed that blood pressure was controlled in only 31% of the hypertension patients between 1999 and 2000 (CitationHajjar and Kotchen 2003). It is likely that non-compliance with treatment contributed to this lack of blood pressure control among the general population. For therapeutic non-compliance in infectious diseases, the consequences can include not only the direct impact such as treatment failures, but also indirect impact or negative externalities as well via the development of resistant microorganisms (CitationSanson-Fisher et al 1992). In addition, it has been shown that almost all patients who had poor compliance with drugs eventually dropped out of treatments completely, and therefore did not benefit at all from the treatment effects (CitationLim and Ngah 1991).

Besides undesirable impact on clinical outcomes, non-compliance would also cause an increased financial burden for society. For example, therapeutic non-compliance has been associated with excess urgent care visits, hospitalizations and higher treatment costs (CitationBond and Hussar 1991, CitationSvarstad et al 2001). It has been estimated that 25% of hospital admissions in Australia, and 33%–69% of medication-related hospital admissions in the USA were due to non-compliance with treatment regimens (CitationSanson-Fisher et al 1992; CitationOsterberg and Blaschke 2005). Additionally, besides direct financial impact, therapeutic non-compliance would have indirect cost implications due to the loss of productivity, without even mentioning the substantial negative effect on patient’s quality of life.

Furthermore, as a result of undetected or unreported therapeutic non-compliance, physicians may change the regimen, which may increase the cost or complexity of the treatment, thus further increasing the burden on the healthcare system. The cost burden has been estimated at US$100 billion each year in the USA alone (CitationVermeire et al 2001). Prescription drug cost is the fastest growing component of healthcare costs in the USA. National outpatient drug spending has increased by 13 to 16% per year during the past few years, and it is expected to continue to grow by 9%–13% per year during the coming decade (CitationSokol et al 2005). In the era where cost-effectiveness is a buzz word in healthcare delivery, any factors that could contribute to increased drug use should be a concern for the healthcare providers.

Hence, from both the perspective of achieving desirable clinical and economic outcomes, the negative effect of therapeutic non-compliance needs to be minimized. However, in order to formulate effective strategies to contain the problem of non-compliance, there is a need to systematically review the factors that contribute to non-compliance. An understanding of the predictive value of these factors on non-compliance would also contribute positively to the overall planning of any disease management program.

Objectives

To conduct a systematic qualitative review to identify the most common factors causing therapeutic non-compliance from the patient’s perspective.

Methods

Literature searches were undertaken through the Medline database from 1970 to 2005. The following MeSH (medical subject heading) terms were used: treatment refusal, patient compliance, and patient dropouts. MeSH terms provide a consistent way to retrieve information that may use different terminology for the same concepts. Besides MeSH terms, the following key words were also searched in the title or abstract: factors, predictors and determinants.

Only English-language journal articles with abstracts were included. The populations were adolescents aged 13–18 years and adults aged 19 years or older. Clinical trials were excluded since they were carried out under close monitoring and therefore the compliance rates reported would not be generalizable. Articles which were categorized by Medline in subsets on AIDS, bioethics, history of medicine, space life sciences and toxicology were not included as well.

Abstracts of identified articles were retrieved manually to select original studies and reviews which mainly focused on the topics of interest. The topics of interest in the field of patient compliance were: factors that influence therapeutic non-compliance and the extent of non-compliance with treatment. Only non-compliance studies from the patient’s perspective were selected. Original studies that included fewer than 50 patients were eliminated because of inadequate sample size. If the sample population of studies was very specific, such as involving only males or females, or recruiting patients from one specific class (homeless, prisoners or workers from one employer, etc), they were eliminated as well because results from these studies might not be generalizable to the general population. In addition, a number of articles were excluded if they mainly focused on strategies to enhance patient’s compliance, methods to measure compliance, validating instruments to identify factors influencing non-compliance and the effect of non-compliance. When the abstracts were not clear enough to decide whether articles met the inclusion criteria, full articles were read to make the decision.

Results

A total of 2095 articles were retrieved in this process, and after the culling process, 102 articles met the inclusion criteria. The rest were excluded for the reasons such as small sample size, not focused on factors affecting compliance, not from patients’ perspective, etc (). The impact of these factors on therapeutic non-compliance would be discussed in details in the subsequent sections.

Factors identified

The factors identified from the studies and reviews may be grouped into several categories, namely, patient-centered factors, therapy-related factors, healthcare system factors, social and economic factors, and disease factors ().

Table 2 Categories of factors identified from the literature review

Patient-centered factors

Demographic factors

Factors identified to be in this group include patient’s age, ethnicity, gender, education, and marital status. A summary of the impact of these factors on therapeutic compliance is presented ().

Table 3 The effect of demographic factors on compliance

Age

More than thirty retrieved articles were related to this factor. The majority of the studies showed that age was related to compliance, although a few researchers found age not to be a factor causing non-compliance (CitationLorenc and Branthwaite 1993; CitationMenzies et al 1993; CitationWild et al 2004; CitationWai et al 2005). From a review of the articles showing a correlation between age and non-compliance, it would appear that the effect of age could be divided into 3 major groups: the elderly group (over 55 years old), the middle-age group (40 to 54 years old) and the young group (under 40 years old).

For elderly people, the results from the various studies are not unidirectional. A large proportion of retrieved studies suggested that they might have higher compliance (CitationNorman et al 1985; CitationDidlake et al 1988; CitationSchweizer et al 1990; CitationShea et al 1992; CitationFrazier et al 1994; CitationMcLane et al 1995; CitationShaw et al 1995; CitationMonane et al 1996; CitationBuck et al 1997; CitationViller et al 1999; CitationSirey et al 2001; CitationKim et al 2002; CitationSenior et al 2004; CitationHertz et al 2005). In a study carried out in UK, patients over 60 years old were more likely to be always compliant with their antiepileptic tablets than patients under 60 years old (86% vs 66%, respectively) (CitationBuck et al 1997). It was also suggested that patients’ antidepressant drug compliance was positively related to age over 60 years (CitationSirey et al 2001). These results are consistent with the conclusion from another published review (CitationKrousel-Wood et al 2004). In addition, four studies focusing on younger people (mean age 46–50 yr) indicated the same trend that compliance increased with the increasing age (CitationDegoulet et al 1983; CitationChristensen and Smith 1995; CitationCaspard et al 2005; CitationLacasse et al 2005).

However, some studies found that advancing age affected compliance among elderly people in the opposite direction (CitationOkuno et al 1999; CitationBenner et al 2002; CitationBalbay et al 2005). Nevertheless, there were confounding factors in these studies. The study by Balbay et al was carried out in a rural area of Turkey among patients with tuberculosis and found that younger patients were more compliant to treatment than older patients (mean age 42 yr vs 50 yr) (CitationBalbay et al 2005). The researchers stated that this might be due to the low education level of older patients. Similarly, the study by Okuno et al suggested that home-care patients aged 80 and over were less likely to be compliant with their prescribed medication, but the participants in that particular study had physical disabilities which limit its generalizability (CitationOkuno et al 1999).

Several studies also attempted to venture plausible reasons for poorer compliance among elderly patients. Elderly patients may have problems in vision, hearing and memory. In addition, they may have more difficulties in following therapy instructions due to cognitive impairment or other physical difficulties, such as having problems in swallowing tablets, opening drug containers, handling small tablets, distinguishing colors or identifying markings on drugs. (CitationMurray et al 1986; CitationStewart and Caranasos 1989; CitationChizzola et al 1996; CitationNikolaus et al 1996; CitationOkuno et al 2001; CitationBenner et al 2002; CitationJeste et al 2003; CitationCooper et al 2005). On the contrary, older people might also have more concern about their health than younger patients, so that older patients’ non-compliance is non-intentional in most cases. As a result, if they can get the necessary help from healthcare providers or family members, they may be more likely to be compliant with therapies.

In comparison, the impact of younger age on compliance is much more congruent among the studies. Middle-aged patients were less likely to be compliant to therapy. In Japan, patients in the prime of their life (40–59 years) were found less likely to be compliant to the medication (CitationIihara et al 2004). Similarly, young patients under 40 years also have a low compliance rate (CitationNeeleman and Mikhail 1997; CitationLeggat et al 1998; CitationLoong 1999; CitationSiegal and Greenstein 1999). In Singapore, patients less than 30 years old were found to be less likely to collect the medication prescribed at a polyclinic (CitationLoong 1999). In a study about patients’ compliance with hemodialysis, patients aged 20 to 39 years were poorly compliant (CitationLeggat et al 1998). Patients in these two age ranges (middle-aged patients and young patients under 40 years old) always have other priorities in their daily life. Due to their work and other commitments, they may not be able to attend to treatment or spend a long time waiting for clinic appointments.

Likewise, low compliance also occurs in adolescents and children with chronic disease (CitationBuck et al 1997; CitationKyngas 1999). Very young children need more help from their parents or guardians to implement treatment. Therefore, their poorer compliance may be due to a lack of understanding or other factors relating to their parents or guardians. For adolescents, this period is often marked by rebellious behavior and disagreement with parents and authorities (CitationTebbi 1993). They usually would prefer to live a normal life like their friends. This priority could therefore influence their compliance.

Ethnicity

Race as a factor causing non-compliance has been studied fairly widely in the USA and European countries and sixteen studies on this factor were retrieved. Caucasians are believed to have good compliance according to some studies (CitationDidlake et al 1988; CitationSharkness and Snow 1992; CitationTurner et al 1995; CitationRaiz et al 1999; CitationThomas et al 2001; CitationYu et al 2005), while African-Americans, Hispanics and other minorities were found to have comparatively poor compliance (CitationSchweizer et al 1990; CitationMonane et al 1996; CitationLeggat et al 1998; CitationBenner et al 2002; CitationApter et al 2003; CitationOpolka et al 2003; CitationSpikmans et al 2003; CitationButterworth et al 2004; CitationKaplan et al 2004; CitationDominick et al 2005). However, a plausible explanation for this may be due to patient’s lower socio-economic status and language barriers of the minority races in the study countries. Hence, due to these confounding variables, ethnicity may not be a true predictive factor of poorer compliance.

Gender

In the twenty-two studies retrieved related to this factor, the results are contradictory. Female patients were found by some researchers to have better compliance (CitationDegoulet et al 1983; CitationChuah 1991; CitationShea et al 1992; CitationKyngas and Lahdenpera 1999; CitationViller et al 1999; CitationKiortsis et al 2000; CitationLindberg et al 2001; CitationBalbay et al 2005; CitationChoi-Kwon 2005; CitationFodor et al 2005; CitationLertmaharit et al 2005), while some studies suggested otherwise (CitationFrazier et al 1994; CitationSung et al 1998; CitationCaspard et al 2005; CitationHertz et al 2005). In addition, some studies could not find a relationship between gender and compliance (CitationMenzies et al 1993; CitationBuck et al 1997; CitationHorne and Weinman 1999; CitationGhods and Nasrollahzadeh 2003; CitationSpikmans et al 2003; CitationSenior et al 2004). This is consistent with another literature review on compliance in seniors that concluded that gender has not been found to influence compliance (CitationVic et al 2004). Gender may not be a good predictor of non-compliance because of the inconsistent conclusions.

Educational level

The effect of educational level on non-compliance was equivocal after reviewing thirteen articles which focused on the impact of educational level as they used different criteria for “higher” and “lower” education. Several studies found that patients with higher educational level might have higher compliance (CitationApter et al 1998; CitationOkuno et al 2001; CitationGhods and Nasrollahzadeh 2003; CitationYavuz et al 2004), while some studies found no association (CitationNorman et al 1985; CitationHorne and Weinman 1999; CitationSpikmans et al 2003; CitationKaona et al 2004; CitationStilley et al 2004; CitationWai et al 2005). Intuitively, it may be expected that patients with higher educational level should have better knowledge about the disease and therapy and therefore be more compliant. However, DiMatteo found that even highly educated patients may not understand their conditions or believe in the benefits of being compliant to their medication regimen (CitationDiMatteo 1995). Other researchers showed that patients with lower education level have better compliance (CitationKyngas and Lahdenpera 1999; CitationSenior et al 2004). A UK study group found that patients without formal educational qualifications had better compliance with cholesterol-lowering medication (CitationSenior et al 2004). Patients with lower educational level might have more trust in physicians’ advice. From these results, it seems that educational level may not be a good predictor of therapeutic compliance.

Marital status

Marital status might influence patients’ compliance with medication positively (CitationSwett and Noones 1989; CitationFrazier et al 1994; CitationDe Geest et al 1995; CitationTurner et al 1995; CitationCooper et al 2005). The help and support from a spouse could be the reason why married patients were more compliant to medication than single patients. However, marital status was not found to be related to patient’s compliance in five recent studies (CitationGhods and Nasrollahzadeh 2003; CitationSpikmans et al 2003; CitationKaona et al 2004; CitationWild et al 2004; CitationYavuz et al 2004). This disparity might be due to the fact that the recent studies investigated the effect of marital status in disease conditions which were different from those evaluated in the older studies, with the impact being masked by the disease factor.

Psychological factors

Patient’s beliefs, motivation and negative attitude towards therapy were identified as factors to be included in this category.

Patients’ beliefs and motivation about the therapy

Twenty-three articles were identified for this factor in the review process. From the results, patients’ beliefs about the causes and meaning of illness, and motivation to follow the therapy were strongly related to their compliance with healthcare (CitationLim and Ngah 1991; CitationBuck et al 1997; CitationCochrane et al 1999; CitationKyngas 1999; CitationKyngas 2001; CitationKyngas and Rissanen 2001; CitationVincze et al 2004).

In summarizing the findings from the various studies, it would appear that compliance was better when the patient had the following beliefs:

The patient feels susceptible to the illness or its complication (CitationHaynes et al 1980; CitationAbbott et al 1996; CitationSpikmans et al 2003).

The patient believes that the illness or its complications could pose severe consequences for his health (CitationMcLane et al 1995; CitationSirey et al 2001; CitationLoffler et al 2003).

The patient believes that the therapy will be effective or perceives benefits from the therapy (CitationLorenc and Branthwaite 1993; CitationDe Geest et al 1995; CitationCochrane et al 1999; CitationHorne and Weinman 1999; CitationApter et al 2003; CitationSpikmans et al 2003; CitationKrousel-Wood et al 2004; CitationWild et al 2004; CitationGonzalez et al 2005; CitationSeo and Min 2005).

On the contrary, misconceptions or erroneous beliefs held by patients would contribute to poor compliance. Patient’s worries about the treatment, believing that the disease is uncontrollable and religious belief might add to the likelihood that they are not compliant to therapy. In a review to identify patient’s barriers to asthma treatment compliance, it was suggested that if the patients were worried about diminishing effectiveness of medication over time, they were likely to have poor compliance with the therapy (CitationBender and Bender 2005). In patients with chronic disease, the fear of dependence on the long-term medication might be a negative contributing factor to compliance (CitationApter et al 2003; CitationBender and Bender 2005). This is sometimes augmented further by cultural beliefs. For example, in Malaysia, some hypertension patients believed long-term use of “Western” medication was “harmful”, and they were more confident in herbal or natural remedies (CitationLim and Ngah 1991). In a New Zealand study, Tongan patients may think disease is God’s will and uncontrollable; and as a consequence, they perceived less need for medication (CitationBarnes et al 2004). Similarly, in Pakistan, inbred fears and supernatural beliefs were reported to be two major factors affecting patients’ compliance with treatment (CitationSloan and Sloan 1981).

Patients who had low motivation to change behaviors or take medication are believed to have poor compliance (CitationLim and Ngah 1991; CitationHernandez-Ronquillo et al 2003; CitationSpikmans et al 2003). In a study done in Malaysia, 85% of hypertension patients cited lack of motivation as the reason for dropping out of treatment (CitationLim and Ngah 1991).

Negative attitude towards therapy

Fifteen studies showed an association between patients’ negative attitude towards therapy (eg, depression, anxiety, fears or anger about the illness) and their compliance (CitationLorenc and Branthwaite 1993; CitationBosley et al 1995; CitationCarney et al 1995; CitationMilas et al 1995; CitationJette et al 1998; CitationClark et al 1999; CitationRaiz et al 1999; CitationSirey et al 2001; CitationBarnes et al 2004; CitationGascon et al 2004; CitationIihara et al 2004; CitationKaplan et al 2004; CitationStilley et al 2004; CitationKilbourne et al 2005; CitationYu et al 2005). In one study conducted in patients older than 65 years with coronary artery disease, depression affected compliance markedly (CitationCarney et al 1995). There were other studies reporting that for children or adolescents, treatment may make them feel stigmatized (CitationBender and Bender 2005), or feel pressure because they are not as normal as their friends or classmates (CitationKyngas 1999). Therefore, negative attitude towards therapy should be viewed as a strong predictor of poor compliance.

Patient-prescriber relationship

Seventeen articles evaluated the effect of the patient-prescriber relationship to patient’s compliance. From these articles it could be concluded that patient-prescriber relationship is another strong factor which affects patients’ compliance (CitationBuck et al 1997; CitationRoter and Hall 1998; CitationStromberg et al 1999; CitationKiortsis et al 2000; CitationOkuno et al 2001; CitationKim et al 2002; CitationLoffler et al 2003; CitationMoore et al 2004; CitationGonzalez et al 2005). A healthy relationship is based on patients’ trust in prescribers and empathy from the prescribers. Studies have found that compliance is good when doctors are emotionally supportive, giving reassurance or respect, and treating patients as an equal partner (CitationMoore et al 2004; CitationLawson et al 2005). Rubin mentioned some situations that may influence patients’ trust in physicians (CitationRubin 2005). For example, physicians who asked few questions and seldom made eye contact with patients, and patients who found it difficult to understand the physician’s language or writing. More importantly, too little time spent with patients was also likely to threaten patient’s motivation for maintaining therapy (CitationLim and Ngah 1991; CitationGascon et al 2004; CitationMoore et al 2004; CitationLawson et al 2005).

Poor communication with healthcare providers was also likely to cause a negative effect on patient’s compliance (CitationBartlett et al 1984; CitationApter et al 1998). Lim and Ngah showed in their study that non-compliant hypertension patients felt the doctors were lacking concern for their problems (CitationLim and Ngah 1991). In addition, multiple physicians or healthcare providers prescribing medications might decrease patients’ confidence in the prescribed treatment (CitationVlasnik et al 2005).

These findings demonstrate the need for cooperation between patients and healthcare providers and the importance of good communication. To build a good and healthy relationship between patients and providers, providers should have patients involved in designing their treatment plan (CitationGonzalez et al 2005; CitationVlasnik et al 2005), and give patients a detailed explanation about the disease and treatment (CitationButterworth et al 2004; CitationGascon et al 2004). Good communication is also very important to help patients understand their condition and therapy (CitationLorenc and Branthwaite 1993).

Health literacy

Health literacy means patients are able to read, understand, remember medication instructions, and act on health information (CitationVlasnik et al 2005). Patients with low health literacy were reported to be less compliant with their therapy (CitationNichols-English and Poirier 2000). On the contrary, patients who can read and understand drug labels were found to be more likely to have good compliance (CitationMurray et al 1986; CitationLorenc and Branthwaite 1993; CitationButterworth et al 2004). Thus, using written instructions and pictograms on medicine labels has proven to be effective in improving patient’s compliance (CitationDowse and Ehlers 2005; CitationSegador et al 2005).

Patient knowledge

Patient’s knowledge about their disease and treatment is not always adequate. Some patients lack understanding of the role their therapies play in the treatment (CitationPonnusankar et al 2004); others lack knowledge about the disease and consequences of poor compliance (CitationAlm-Roijer et al 2004; CitationGascon et al 2004); or lack understanding of the value of clinic visits (CitationLawson et al 2005). Some patients thought the need for medication was intermittent, so they stopped the drug to see whether medication was still needed (CitationVic et al 2004; CitationBender and Bender 2005). For these reasons, patient education is very important to enhance compliance. Counseling about medications is very useful in improving patient’s compliance (CitationPonnusankar et al 2004). Healthcare providers should give patients enough education about the treatment and disease (CitationHaynes et al 1980; CitationNorman et al 1985; CitationStanton 1987; CitationOlubodun et al 1990; CitationLorenc and Branthwaite 1993; CitationMenzies et al 1993; CitationMilas et al 1995; CitationChizzola et al 1996; CitationHungin 1999; CitationLiam et al 1999; CitationOkuno et al 1999; CitationViller et al 1999; CitationLindberg et al 2001; CitationThomas et al 2001; CitationGascon et al 2004; CitationIihara et al 2004; CitationKaona et al 2004; CitationPonnusankar et al 2004; CitationSeo and Min 2005).

However, education is not always “the more the better”. An “inverted U” relationship between knowledge and compliance existed in adolescents. Adolescent patients who knew very little about their therapies and illness were poor compliers, while patients who were adequately educated about their disease and drug regimens were good compliers; but patients who knew the life-long consequences might show poor compliance (CitationHamburg and Inoff 1982). Nevertheless, there is no report of similar observations in other age groups. In addition, patients’ detailed knowledge of the disease was not always effective. In Hong Kong, researchers could not find any association between diabetes knowledge and compliance. They suggested that there was a gap between what the patients were taught and what they were actually doing (CitationChan and Molassiotis 1999).

In addition, the content of education is crucial. Rubin found that educating the patients about their disease state and general comprehension of medications would increase their active participation in treatment (CitationRubin 2005). Making sure patients understand the drug dosing regimen could also improve compliance (CitationOlubodun et al 1990). To make sure patients remember what was taught, written instructions work better than verbal ones, as patients often forget physician’s advice and statements easily (CitationTebbi 1993).

Other factors

Smoking or alcohol intake

Several studies about compliance among asthma, hypertension and renal transplantation patients found that patients who smoked or drank alcohol were more likely to be non-compliant (CitationDegoulet et al 1983; CitationShea et al 1992; CitationTurner et al 1995; CitationLeggat et al 1998; CitationKyngas 1999; CitationKyngas and Lahdenpera 1999; CitationKiortsis et al 2000; CitationKim et al 2002; CitationGhods and Nasrollahzadeh 2003; CitationYavuz et al 2004; CitationBalbay et al 2005; CitationCooper et al 2005; CitationFodor et al 2005). In a study conducted in Finland in hypertension patients, non-smokers were more compliant to the diet restrictions (CitationKyngas and Lahdenpera 1999). Likewise, another study in renal transplantation patients in Turkey found that patients who were smoking or drinking were unlikely to be compliant to the therapy (CitationYavuz et al 2004). Only one single study about obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (OSAHS) found no relationship between smoking or alcohol intake and patient’s compliance with continuous positive airway pressure treatment (CitationWild et al 2004).

Forgetfulness

Forgetfulness is a widely reported factor that causes non-compliance with medication or clinic appointments (CitationCummings et al 1982; CitationKelloway et al 1994; CitationOkuno et al 2001; CitationHernandez-Ronquillo et al 2003; CitationPonnusankar et al 2004; CitationWai et al 2005). A Japanese study in elderly home-care recipients found an interesting association between meal frequency and compliance. Patients having less than 3 meals per day were less compliant than patients having 3 meals a day. It suggested that meal frequency was an effective tool to remind the patient to take drugs (CitationOkuno et al 1999). As mentioned in a previous section, written instructions are better than oral advice for reminding patients to take medication.

Therapy-related factors

Therapy-related factors identified include: route of administration, treatment complexity, duration of treatment period, medication side effects, degree of behavioral change required, taste of medication and requirement for drug storage ().

Table 4 The effect of therapy-related factors on compliance

Route of administration

Medications with a convenient way of administration (eg, oral medication) are likely to make patients compliant. Studies in asthma patients compared compliance between oral and inhaled asthma medications, and found patients had better compliance with oral medication (CitationKelloway et al 1994; CitationNichols-English and Poirier 2000). Likewise, difficulty in using inhalers contributes to non-compliance in patients with asthma (CitationBender and Bender 2005).

Treatment complexity

Complex treatment is believed to threaten the patient’s compliance. However, compliance does not seem to correlate with the number of drugs prescribed (CitationHorne and Weinman 1999; CitationPatal and Taylor 2002; CitationGrant et al 2003; CitationIihara et al 2004), but the number of dosing times every day of all prescribed medications (CitationKass et al 1986; CitationCockburn et al 1987; CitationCramer et al 1989; CitationEisen et al 1990; CitationCramer 1998; CitationSung et al 1998; CitationClaxton et al 2001; CitationIskedjian et al 2002). The rate of compliance decreased as the number of daily doses increased. This is illustrated by one study where compliance was assessed by pill counts and self-reports that showed that non-compliance increased with an increase in the frequency of prescribed dosing: 20% for once daily; 30% for twice daily; 60% for three times a day; and 70% for four times daily (CitationCramer et al 1989). Similarly, a meta-analysis found that there was a significant difference in compliance rate between patients taking antihypertensive medication once daily and twice daily (92.1% and 88.9%, respectively) (CitationIskedjian et al 2002). Thus, simplifying the medication dosing frequency could improve compliance markedly.

Duration of the treatment period

Acute illnesses are associated with higher compliance than chronic illnesses (CitationGascon et al 2004). In addition, longer duration of the disease may adversely affect compliance (CitationFarmer et al 1994; CitationFrazier et al 1994). Similarly, a longer duration of treatment period might also compromise patient’s compliance (CitationMenzies et al 1993; CitationGhods and Nasrollahzadeh 2003; CitationDhanireddy et al 2005). In one trial that compared 6-month and 9-month treatment of tuberculosis, compliance rates were 60% and 50% for the two regimens, respectively (CitationCombs et al 1987). In another study comparing preventive regimens of 3, 6 and 12 months, compliance rates were 87%, 78% and 68% for the three regimens, respectively (CitationInternational Union Against Tuberculosis 1982).

However, some studies about chronic diseases found that longer duration of the disease resulted in good compliance (CitationSharkness and Snow 1992; CitationGaray-Sevilla et al 1995), and newly diagnosed patients had poor compliance (CitationCaro et al 1999). This may indicate that compliance is improved because patient’s attitude of denying the disease is reduced and they accepted treatment after years of suffering from the disease.

Medication side effects

All of the seventeen studies on side effects factor found that side effects threaten patient’s compliance (CitationSpagnoli et al 1989; CitationShaw et al 1995; CitationBuck et al 1997; CitationDusing et al 1998; CitationHungin 1999; CitationKiortsis et al 2000; CitationLinden et al 2000; CitationKim et al 2002; CitationDietrich et al 2003; CitationGrant et al 2003; CitationLoffler et al 2003; CitationSleath et al 2003; CitationIihara et al 2004; CitationKaplan et al 2004; CitationPonnusankar et al 2004; CitationO’Donoghue 2004). In a German study, the second most common reason for non-compliance with antihypertensive therapy was adverse effects (CitationDusing et al 1998). The effect of side effects on compliance may be explained in terms of physical discomfort, skepticism about the efficacy of the medication, and decreasing the trust in physicians (CitationChristensen 1978).

Degree of behavioral change required

The degree of required behavioral change is related to patients’ motivation to be compliant with the therapy (CitationMilas et al 1995; CitationHernandez-Ronquillo et al 2003; CitationVincze et al 2004). A study done in Mexico demonstrated that patients with type 2 diabetes could not follow the diet because of the difficulty of changing their dietary habits (CitationHernandez-Ronquillo et al 2003).

Social and economic factors

Social and economic factors include: time commitment, cost of therapy, income and social support.

Time commitment

Patients may not be able to take time off work for treatment; as a result, their rate of compliance could be threatened (CitationShaw et al 1995; CitationSiegal and Greenstein 1999; CitationHernandez-Ronquillo et al 2003; CitationLawson et al 2005; CitationNeal et al 2005). Therefore, a shorter traveling time between residence and healthcare facilities could enhance patient’s compliance (CitationGonzalez et al 2005). A study suggested that white collar patients have poor compliance because they have other priorities (CitationSiegal and Greenstein 1999). Housewives with tuberculosis were more compliant to therapy in an observational study in Malaysia (CitationChuah 1991). This may be because housewives can adapt well to clinic appointment times and treatment.

Cost of therapy and income

Cost is a crucial issue in patient’s compliance especially for patients with chronic disease as the treatment period could be life-long (CitationConnelly 1984; CitationShaw et al 1995; CitationEllis et al 2004; CitationPonnusankar et al 2004). Healthcare expenditure could be a large portion of living expenses for patients suffering from chronic disease. Cost and income are two interrelated factors. Healthcare cost should not be a big burden if the patient has a relatively high income or health insurance. A number of studies found that patients who had no insurance cover (CitationSwett and Noones 1989; CitationKaplan et al 2004; CitationChoi-Kwon 2005), or who had low income (CitationDegoulet et al 1983; CitationCockburn et al 1987; CitationShea et al 1992; CitationFrazier et al 1994; CitationApter et al 1998; CitationBerghofer et al 2002; CitationBenner et al 2002; CitationGhods and Nasrollahzadeh 2003; CitationHernandez-Ronquillo et al 2003; CitationMishra et al 2005) were more likely to be non-compliant to treatment. However, even for patients with health insurance, health expenses could still be a problem. More than one in ten seniors in the USA reported using less of their required medications because of cost (Congressional Budget Office 2003). Nevertheless, in other cases, income was not related to compliance level (CitationNorman et al 1985; CitationLim and Ngah 1991; CitationPatal and Taylor 2002; CitationStilley et al 2004; CitationWai et al 2005). In Singapore, a study on chronic hepatitis B surveillance found that monthly income was not related to patient’s compliance with regular surveillance (CitationWai et al 2005). This discrepancy might due to different healthcare systems in different countries. Healthcare personnel should be aware of patient’s economic situation and help them use medication more cost-effectively.

Social support

The general findings from these articles showed that patients who had emotional support and help from family members, friends or healthcare providers were more likely to be compliant to the treatment (CitationStanton 1987; CitationLorenc and Branthwaite 1993; CitationGaray-Sevilla et al 1995; CitationMilas et al 1995; CitationKyngas 1999; CitationOkuno et al 1999; CitationStromberg et al 1999; CitationKyngas 2001; CitationKyngas and Rissanen 2001; CitationThomas et al 2001; CitationLoffler et al 2003; CitationDiMatteo 2004; CitationFeinstein et al 2005; CitationSeo and Min 2005; CitationVoils et al 2005). The social support helps patients in reducing negative attitudes to treatment, having motivation and remembering to implement the treatment as well.

Healthcare system factors

The main factor identified relating to healthcare systems include availability and accessibility. Lack of accessibility to healthcare (CitationPonnusankar et al 2004), long waiting time for clinic visits (CitationGrunebaum et al 1996; CitationBalkrishnan et al 2003; CitationMoore et al 2004; CitationLawson et al 2005; CitationWai et al 2005), difficulty in getting prescriptions filled (CitationCummings et al 1982; CitationVlasnik et al 2005), and unhappy or unsatisfied clinic visits (CitationSpikmans et al 2003; CitationGascon et al 2004; CitationLawson et al 2005) all contributed to poor compliance. The above observation is further supported by another study that showed patient’s satisfaction with clinic visits is most likely to improve their compliance with the treatment (CitationHaynes et al 1980).

Disease factor

Patients who are suffering from diseases with fluctuation or absence of symptoms (at least at the initial phase), such as asthma and hypertension, might have a poor compliance (CitationHungin 1999; CitationKyngas and Lahdenpera 1999; CitationVlasnik et al 2005). Kyngas and Lahdenpera demonstrated that there was a significant relationship between the presence of hypertension symptoms and reduction in the sodium consumption. Seventy-one percent of the patients who had symptoms reduced the use of sodium, as compared to only 7% of the patients who did not suffer from symptoms (CitationKyngas and Lahdenpera 1999). Patients who had marked improvement in symptoms with the help of treatment normally had better compliance (CitationLim et al 1992; CitationViller et al 1999; CitationGrant et al 2003).

In addition, no consistent evidence shows that subjects with greater disease severity based on clinical evaluation comply better with medications than healthier ones (CitationMatthews and Hingson 1977; CitationKyngas 1999; CitationWild et al 2004; CitationSeo and Min 2005). A study in patients with OSAHS found that greater disease severity based on clinical variables predicted better compliance (CitationWild et al 2004). However, a study on compliance in adolescents with asthma showed that only patients with mild severity had good compliance (CitationKyngas 1999). Similarly, Matthews et al suggested that the actual severity of the illness (based on the physician’s clinical evaluation) was not related to compliance (CitationMatthews and Hingson 1977). Instead of actual disease severity, perceived health status may have more significant influence on compliance. Patients expecting poor health status are more motivated to be compliant with treatment if they consider the medication to be effective (CitationRosenstock et al 1988). In a study conducted in the USA in patients on antihyperlipidemic medications, patients with a perception of poor health status were more compliant with treatment (CitationSung et al 1998). This supports the suggestion that how patients feel plays a crucial role in predicting compliance.

Discussion

From the literature review, it can be concluded that although several terms have been used, the terms are used more or less interchangeably in clinical practice and therefore, the definition of compliance is adequately defined in the practical context. However, one alarming observation is that non-compliance remains a major issue in enhancing healthcare outcomes in spite of the many studies highlighting the problem over the years.

In this review we attempted to identify factors related to compliance which would have wide generalizability, and we retrieved original studies investigating non-compliance from different diseases, population settings and different countries. In the process, we identified a wide array of influencing factors. Although some factors’ effect on compliance is complex and not unequivocal, several factors with consistent impact on compliance have been identified through the review process.

Firstly, addressing therapy-related factors should contribute positively in improving patient’s compliance. Prescribing medication with non-invasive route of administration (eg, oral medication) and simple dosing regimens might motivate patients to be compliant. Long duration of treatment period and medication side effects might compromise patient’s beliefs about medication effectiveness. Therefore, healthcare providers should consider therapy-related problems when designing the therapy plan and involve the patients in the process to minimize the possible therapeutic barriers.

Besides therapy-related factors, healthcare system problems were found to be significantly related to compliance. Accessibility and satisfaction with the healthcare facilities are important contributors to compliance because patient’s satisfaction with healthcare is crucial for their compliance. Long waiting time for clinic visits and unhappy experience during clinic visits was indicated by many studies. A healthcare system designed with convenient accessibility and patient satisfaction in mind would be a great help for compliance issue.

Thirdly, compliance is also related with disease characteristics. Non-compliance is usually not a prevalent issue in acute illness or illness of short duration. In contrast, patients who are suffering from chronic diseases, in particular those with fluctuation or absence of symptoms (eg, asthma and hypertension) are likely to be non-compliant. Special efforts and attention should be paid to address the issue of non-compliance in chronic disease patients.

Lastly, healthcare expenditure is a very important factor for patients with chronic diseases because the treatment could be life-long so the cost of therapy would constitute a large portion of their disposable income. If the patient feels that the cost of therapy is a financial burden, the compliance with therapy will definitely be threatened. Healthcare personnel should be aware of patient’s economic situation during the planning of a treatment regimen, and a healthcare finance system that provides at least some financial assistance to low income patients would be helpful to boost compliance.

These factors discussed so far are directly and clearly related to patient’s compliance. We can call them the “hard” factors. We are using this term as the impact of factors identified is more quantifiable. By and large, these “hard” factors are amendable to a certain extent by counseling and communication by healthcare providers. In additional, the society could also participate in minimizing the barriers for patients to follow the therapy.

In contrast with “hard” factors, some other factors might be classified as “soft” factors because their effects are much more difficult to measure and counter. In fact, a failure to address the “soft” factors may negate all efforts spent in countering the effects of the “hard” factors.

Psycho-social factors such as patient’s beliefs, attitude towards therapy and their motivation to the therapy could be classified as “soft” factors. Since the 1990’s, research has focused more on the patient-provider relationship and patients’ beliefs about the therapies. For patients with chronic diseases, they would do their own cost-benefit analysis of therapy, either consciously or subconsciously. It means they weigh the benefits from compliance with therapy (ie, controlling symptoms and preventing medical complications) against constraints on their daily lives and perceived risks of therapy such as side effects, time and effort involved (CitationDonovan and Blake 1992). Sometimes, they may have the wrong beliefs based on inadequate health knowledge or a negative relationship with the healthcare provider. Hence, patients should be given adequate knowledge about the purpose of the therapy and consequences of non-compliance. In addition, a healthy relationship and effective communication between the patient and healthcare provider would enhance patient’s compliance. In fact, the effects of patient’s beliefs, health knowledge and relationship with the healthcare provider are very complex because these “soft” factors are inter-related with each other. The interaction is a bit like antibiotic combinations. Sometimes the effect would be additive or synergistic, while other times the effect would be antagonistic. However, due to the design of the studies performed so far, it is difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate precisely whether the interaction between these factors would be additive, synergistic or antagonistic. More robust and better designed studies would be needed in future to elucidate this effect.

Similar to the “soft” factors, the effect of demographic factors (eg, age, gender, ethnicity, educational level and marital status) on compliance is also rather complicated, because they may not be truly independent factors influencing compliance. Actually, demographic factors are related to patient’s various cultural, socioeconomic and psychological backgrounds. Thus, future studies on compliance should not focus on demographic factors alone.

Definitely, there are some limitations in the current review. Firstly, only one electronic database, PubMed, was searched and only English articles were included. It might be possible that some informative studies in other literature databases or in other languages were omitted. Secondly, there is a shortcoming in the search strategy in that only articles with abstracts were retrieved. There are quite a number of studies published in 1970s and early 1980s without abstracts that were not screened. However, we do believe that the review so far has captured most of the key factors with potential influence on therapeutic compliance from the patient’s perspective.

In conclusion, from the review of the literature starting from the 1970s to identify relevant factors relating to therapeutic compliance, the evidence indicates that non-compliance is still commonplace in healthcare and no substantial change occurred despite the large number of studies attempting to address and highlight the problem. In addition, too few studies are being done systematically to quantify the impact of non-compliance on health and financial outcomes. The magnitude of the impact of non-compliance needs to be studied in future compliance research due to the potential tremendous implication of poor compliance on clinical and economic outcomes. Finally, few studies on compliance have been performed in Asian and developing countries where most of the world’s population resides. More studies on factors influencing compliance in these countries or regions would be helpful to fill in the knowledge gap and contribute to formulating international strategies for countering non-compliance.

References

- AbbottJDoddMWebbAKHealth perceptions and treatment adherence in adults with cystic fibrosisThorax199651123388994521

- Alm-RoijerCStagmoMUdenGBetter knowledge improves adherence to lifestyle changes and medication in patients with coronary heart diseaseEur J Cardiovasc Nurs200433213015572021

- ApterAJReisineSTAffleckGAdherence with twice-daily dosing of inhaled steroids. Socioeconomic and health-belief differencesAm J Respir Crit Care Med1998157181079620910

- ApterAJBostonRCGeorgeMModifiable barriers to adherence to inhaled steroids among adults with asthma: it’s not just black and whiteJ Allergy Clin Immunol200311112192612789220

- AvornJMonetteJLacourAPersistence of use of lipid-lowering medications: a cross national studyJAMA19982791458629600480

- BalbayOAnnakkayaANArbakPWhich patients are able to adhere to tuberculosis treatment? A study in a rural area in the northwest part of TurkeyJpn J Infect Dis200558152815973006

- BalkrishnanRRajagopalanRCamachoFTPredictors of medication adherence and associated health care costs in an older population with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal cohort studyClin Ther20032529587114693318

- BarnesLMoss-MorrisRKaufusiMIllness beliefs and adherence in diabetes mellitus: a comparison between Tongan and European patientsN Z Med J2004117U74314999303

- BartlettEEGraysonMBarkerRThe effects of physician communications skills on patient satisfaction; recall, and adherenceJ Chronic Dis198437755646501547

- BenderBGBenderSEPatient-identified barriers to asthma treatment adherence: responses to interviews, focus groups, and questionnairesImmunol Allergy Clin N Am20052510730

- BennerJSGlynnRJMogunHLong-term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patientsJAMA20022884556112132975

- BerghoferGSchmidlFRudasSPredictors of treatment discontinuity in outpatient mental health careSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol2002372768212111033

- BondWSHussarDADetection methods and strategies for improving medication complianceAm J Hosp Pharm1991481978881928147

- BosleyCMFosburyJACochraneGMThe psychological factors associated with poor compliance with treatment in asthmaEur Respir J199588999047589375

- BuckDJacobyABakerGAFactors influencing compliance with antiepileptic drug regimesSeizure1997687939153719

- BurnierMSantschiVFavratBMonitoring compliance in resistant hypertension: an important step in patient managementJ Hypertens Suppl200321S374212929906

- ButterworthJRBanfieldLMIqbalTHFactors relating to compliance with a gluten-free diet in patients with coeliac disease: comparison of white Caucasian and South Asian patientsClin Nutr20042311273415380905

- CarneyRMFreedlandKEEisenSAMajor depression and medication adherence in elderly patients with coronary artery diseaseHealth Psychol19951488907737079

- CaroJJSalasMSpeckmanJLPersistence with treatment for hypertension in actual practiceCMAJ19991603179934341

- CaspardHChanAKWalkerAMCompliance with a statin treatment in a usual-care setting: retrospective database analysis over 3 years after treatment initiation in health maintenance organization enrollees with dyslipidemiaClin Ther20052716394616330301

- CerkoneyKAHartLKThe relationship between the health belief model and compliance of persons with diabetes mellitusDiabetes Care1980359487002514

- ChanYMMolassiotisAThe relationship between diabetes knowledge and compliance among Chinese with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in Hong KongJ Adv Nurs199930431810457246

- ChizzolaPRMansurAJda LuzPLCompliance with pharmacological treatment in outpatients from a Brazilian cardiology referral centerSao Paulo Med J19961141259649239925

- Choi-KwonSKwonSUKimJSCompliance with risk factor modification: early-onset versus late-onset stroke patientsEur Neurol2005542041116401893

- ChristensenAJSmithTWPersonality and patient adherence: correlates of the five-factor model in renal dialysisJ Behav Med199518305137674294

- ChristensenDBDrug-taking compliance: a review and synthesisHealth Serv Res19781317187649415

- ChuahSYFactors associated with poor patient compliance with antituberculosis therapy in Northwest Perak, MalaysiaTubercle19917226141811356

- ClarkNJonesPKellerSPatient factors and compliance with asthma therapyRespir Med1999938566210653046

- ClaxtonAJCramerJPierceCA systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication complianceClin Ther200123129631011558866

- CramerJAMattsonRHPreveyMLHow often is medication taken as prescribed? A novel assessment techniqueJAMA1989261327372716163

- CramerJAScheyerRDMattsonRHCompliance declines between clinic visitsArch Intern Med19901501509102369248

- CramerJAEnhancing patient compliance in the elderly. Role of packaging aids and monitoringDrugs Aging1998127159467683

- CochraneGMHorneRChanezPCompliance in asthmaRespir Med199993763910603624

- CockburnJGibberdRWReidALDeterminants of non-compliance with short term antibiotic regimensBr Med J (Clin Res Ed)19872958148

- CombsDLO’BrienRJGeiterLJCompliance with tuberculosis regimes: results from USPHS therapy trial 21Am Rev Respir Dis1987135A138

- Congressional Budget OfficePrescription drug coverage and Medicare’s fiscal challenges2003 [online] Accessed on 1 March 2007.URL: http://www.cbo.gov/showdoc.cfm?index=4159&sequence=0

- ConnellyCECompliance with outpatient lithium therapyPerspect Psychiatr Care19842244506570862

- CooperCCarpenterIKatonaCThe AdHOC study of older adults’ adherence to medication in 11 countriesAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20051310677616319299

- CummingsKMKirschtJPBinderLRDeterminants of drug treatment maintenance among hypertensive persons in inner city DetroitPublic Health Rep198297991066977786

- De GeestSBorgermansLGemoetsHIncidence, determinants, and consequences of subclinical noncompliance with immunosuppressive therapy in renal transplant recipientsTransplantation19955934077871562

- DegouletPMenardJVuHAFactors predictive of attendance at clinic and blood pressure control in hypertensive patientsBr Med J (Clin Res Ed)19832878893

- DhanireddyKKManiscalcoJKirkADIs tolerance induction the answer to adolescent non-adherence?Pediatr Transplant200593576315910394

- DidlakeRHDreyfusKKermanRHPatient noncompliance: a major cause of late graft failure in cyclosporine-treated renal transplantsTransplant Proc1988206393291299

- DietrichAJOxmanTEBurnsMRApplication of a depression management office system in community practice: a demonstrationJ Am Board Fam Pract2003161071412665176

- DiMatteoMRPatient adherence to pharmacotherapy: the importance of effective communicationFormulary1995305968601260510151723

- DiMatteoMRSocial support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysisHealth Psychol2004232071815008666

- DominickKLGolightlyYMBosworthHBRacial differences in analgesic/anti-inflammatory medication adherence among patients with osteoarthritisEthn Dis2005151162215720058

- DonovanJLBlakeDRPatient non-compliance: deviance or reasoned decision-making?Soc Sci Med199234507131604357

- DowseREhlersMMedicine labels incorporating pictograms: do they influence understanding and adherence?Patient Educ Couns200558637015950838

- DusingRWeisserBMengdenTChanges in antihypertensive therapy-the role of adverse effects and complianceBlood Press19987313510321445

- EisenSAMillerDKWoodwardRSThe effect of prescribed daily dose frequency on patient medication complianceArch Intern Med1990150188142102668

- EllisJJEricksonSRStevensonJGSuboptimal statin adherence and discontinuation in primary and secondary prevention populationsJ Gen Intern Med2004196384515209602

- FarmerKCJacobsEWPhillipsCRLong-term patient compliance with prescribed regimens of calcium channel blockersClin Ther199416316268062325

- FeinsteinAROn white-coat effects and the electronic monitoring of complianceArch Intern Med1990150137782369237

- FeinsteinSKeichRBecker-CohenRIs noncompliance among adolescent renal transplant recipients inevitable?Pediatrics20051159697315805372

- FodorGJKotrecMBacskaiKIs interview a reliable method to verify the compliance with antihypertensive therapy? An international central-European studyJ Hypertens2005231261615894903

- FrazierPADavis-AliSHDahlKECorrelates of noncompliance among renal transplant recipientsClin Transplant1994855077865918

- Garay-SevillaMENavaLEMalacaraJMAdherence to treatment and social support in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitusJ Diabetes Complications199598167599352

- GasconJJSanchez-OrtunoMLlorBTreatment Compliance in Hypertension Study Group. Why hypertensive patients do not comply with the treatment: results from a qualitative studyFam Pract2004211253015020377

- GhodsAJNasrollahzadehDNoncompliance with immunnosuppressive medications after renal transplantationExp Clin Transplant20031394715859906

- GonzalezJWilliamsJWJrNoelPHAdherence to mental health treatment in a primary care clinicJ Am Board Fam Pract200518879615798137

- GordisLHaynesBTaylorDWSackettDLConceptual and methodologic problem in measuring patient complianceCompliance in health care1979BaltimoreThe John Hopkins University Press2345

- GrantRWDevitaNGSingerDEPolypharmacy and medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetesDiabetes Care20032614081212716797

- GrunebaumMLuberPCallahanMPredictors of missed appointments for psychiatric consultations in a primary care clinicPsychiatr Serv199647848528837157

- HajjarIKotchenTATrends in prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988-2000JAMA200329019920612851274

- HamburgBAInoffGERelationships between behavioral factors and diabetic control in children and adolescents: a camp studyPsychosom Med198244321397146242

- HaynesRBTaylorDWSackettDLCan simple clinical measurements detect patient noncompliance?Hypertension19802757647007235

- Hernandez-RonquilloLTellez-ZentenoJFGarduno-EspinosaJFactors associated with therapy noncompliance in type-2 diabetes patientsSalud Publica Mex200345191712870420

- HertzRPUngerANLustikMBAdherence with pharmacotherapy for type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study of adults with employer-sponsored health insuranceClin Ther20052710647316154485

- HopeCJWuJTuWAssociation of medication adherence, knowledge, and skills with emergency department visits by adults 50 years or older with congestive heart failureAm J Health Syst Pharm2004612043915509127

- HorneRWeinmanJPatients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illnessJ Psychosom Res1999475556710661603

- HunginAPRubinGO’FlanaganHFactors influencing compliance in long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy in general practiceBr J Gen Pract199949463410562747

- IiharaNTsukamotoTMoritaSBeliefs of chronically ill Japanese patients that lead to intentional non-adherence to medicationJ Clin Pharm Ther2004294172415482384

- InksterMEDonnanPTMacDonaldTMAdherence to antihypertensive medication and association with patient and practice factorsJ Hum Hypertens200620295716424861

- International Union Against Tuberculosis Committee on ProphylaxisEfficacy of various durations of isoniazid preventive therapy for tuberculosis: five years of follow-up in the IUAT trialBull World Health Organ19826055664

- IskedjianMEinarsonTRMacKeiganLDRelationship between daily dose frequency and adherence to antihypertensive pharmacotherapy: evidence from a meta-analysisClin Ther2002243021611911560

- JesteSDPattersonTLPalmerBWCognitive predictors of medication adherence among middle-aged and older outpatients with schizophreniaSchizophr Res200363495812892857

- JetteAMRooksDLachmanMHome-based resistance training: predictors of participation and adherenceGerontologist199838412219726128

- KaonaFATubaMSiziyaSAn assessment of factors contributing to treatment adherence and knowledge of TB transmission among patients on TB treatmentBMC Public Health2004296815625004

- KaplanRCBhalodkarNCBrownEJJrRace, ethnicity, and sociocultural characteristics predict noncompliance with lipid-lowering medicationsPrev Med20043912495515539064

- KassMAMeltzerDWGordonMCompliance with topical pilocarpine treatmentAm J Ophthalmol1986101515233706455

- KellowayJSWyattRAAdlisSAComparison of patients’ compliance with prescribed oral and inhaled asthma medicationsArch Intern Med19941541349528002686

- KilbourneAMReynoldsCF3GoodCBHow does depression influence diabetes medication adherence in older patients?Am J Geriatr Psychiatry2005132021015728751

- KimYSSunwooSLeeHRDeterminants of non-compliance with lipid-lowering therapy in hyperlipidemic patientsPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf20021159360012462137

- KiortsisDNGiralPBruckertEFactors associated with low compliance with lipid-lowering drugs in hyperlipidemic patientsJ Clin Pharm Ther2000254455111123498

- Krousel-WoodMAThomasSMuntnerPMedication adherence: a key factor in achieving blood pressure control and good clinical outcomes in hypertensive patientsCurr Opin Cardiol2004193576215218396

- KyngasHACompliance of adolescents with asthmaNurs Health Sci1999119520210894643

- KyngasHLahdenperaTCompliance of patients with hypertension and associated factorsJ Ad Nurs1999298329

- KyngasHPredictors of good compliance in adolescents with epilepsySeizure2001105495311792154

- KyngasHRissanenMSupport as a crucial predictor of good compliance of adolescents with a chronic diseaseJ Clin Nurs2001107677411822848

- LacasseYArchibaldHErnstPPatterns and determinants of compliance with inhaled steroids in adults with asthmaCan Respir J200512211716003458

- LawsonVLLynePAHarveyJNUnderstanding why people with type 1 diabetes do not attend for specialist advice: a qualitative analysis of the views of people with insulin-dependent diabetes who do not attend diabetes clinicJ Health Psychol2005104092315857871

- LeggatJEJrOrzolSMHulbert-ShearonTENoncompliance in hemodialysis: predictors and survival analysisAm J Kidney Dis199832139459669435

- LertmaharitSKamol-RatankulPSawertHFactors associated with compliance among tuberculosis patients in ThailandJ Med Assoc Thai200588Suppl 4S1495616623020

- LiamCKLimKHWongCMAttitudes and knowledge of newly diagnosed tuberculosis patients regarding the disease, and factors affecting treatment complianceInt J Tuberc Lung Dis19993300910206500

- LimTONgahBAThe Mentakab hypertension study project. Part II – why do hypertensives drop out of treatment?Singapore Med J199132249511776004

- LimTONgahBARahmanRAThe Mentakab hypertension study project Part V – Drug compliance in hypertensive patientsSingapore Med J1992336361598610

- LindbergMEkstromTMollerMAsthma care and factors affecting medication compliance: the patient’s point of viewInt J Qual Health Care2001133758311669565

- LindenMGotheHDittmannRWEarly termination of antidepressant drug treatmentJ Clin Psychopharmacol2000205233011001236

- LofflerWKilianRToumiMSchizophrenic patients’ subjective reasons for compliance and noncompliance with neuroleptic treatmentPharmacopsychiatry2003361051212806568

- LoongTWPrimary non-compliance in a Singapore polyclinicSingapore Med J199940691310709406

- LorencLBranthwaiteAAre older adults less compliant with prescribed medication than younger adults?Br J Clin Psychol199332485928298546

- MatthewsDHingsonRImproving patient compliance: a guide for physiciansMed Clin North Am19776187989875526

- McLaneCGZyzanskiSJFlockeSAFactors associated with medication noncompliance in rural elderly hypertensive patientsAm J Hypertens1995820697755952

- MenziesRRocherIVissandjeeBFactors associated with compliance in treatment of tuberculosisTuber Lung Dis1993743278495018

- MilasNCNowalkMPAkpeleLFactors associated with adherence to the dietary protein intervention in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease StudyJ Am Diet Assoc19959512953007594126

- MishraPHansenEHSabroeSSocio-economic status and adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a case-control study in a district of NepalInt J Tuberc Lung Dis200591134916229225

- MonaneMBohnRLGurwitzJHCompliance with antihypertensive therapy among elderly Medicaid enrollees: the roles of age, gender, and raceAm J Public Health199686180589003143

- MoorePJSickelAEMalatJPsychosocial factors in medical and psychological treatment avoidance: the role of the doctor-patient relationshipJ Health Psychol200494213315117541

- MurrayMDDarnellJWeinbergerMFactors contributing to medication noncompliance in elderly public housing tenantsDrug Intell Clin Pharm198620146523948692

- NealRDHussain-GamblesMAllgarVLReasons for and consequences of missed appointments in general practice in the UK: questionnaire survey and prospective review of medical recordsBMC Fam Pract200564716274481

- NeelemanJMikhailWIA case control study of GP and patient-related variables associated with nonattendance at new psychiatric outpatient appointmentsJ Mental Health199763016

- Nichols-EnglishGPoirierSOptimizing adherence to pharmaceutical care plansJ Am Pharm Assoc20004047585

- NikolausTKruseWBachMElderly patients’ problems with medication. An in-hospital and follow-up studyEur J Clin Pharmacol19964925598857069

- NormanSAMarconiKMSchezelGWBeliefs, social normative influences, and compliance with antihypertensive medicationAm J Prev Med198511073870899

- O’DonoghueMNCompliance with antibioticsCutis200473Suppl 530215182166

- OkunoJYanagiHTomuraSCompliance and medication knowledge among elderly Japanese home-care recipientsEur J Clin Pharmacol199955145910335910

- OkunoJYanagiHTomuraSIs cognitive impairment a risk factor for poor compliance among Japanese elderly in the community?Eur J Clin Pharmacol2001575899411758637

- OlubodunJOBFalaseAOColeTODrug compliance in hypertensive Nigerians with and without heart failureInt J Cardiol199027229342365511

- OpolkaJLRascatiKLBrownCMRole of ethnicity in predicting antipsychotic medication adherenceAnn Pharmacother2003376253012708934

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med20053534879716079372

- Oxford advanced learner’s dictionary of current English20057OxfordOxford University Press296 compliance

- PatalRPTaylorSDFactors affecting medication adherence in hypertensive patientsAnn Pharmacother20023640511816255

- PonnusankarSSurulivelrajanMAnandamoorthyNAssessment of impact of medication counseling on patients’ medication knowledge and compliance in an outpatient clinic in South IndiaPatient Educ Couns200454556015210260

- RaizLRKiltyKMHenryMLMedication compliance following renal transplantationTransplantation19996851510428266

- RubinRRAdherence to pharmacologic therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitusAm J Med200511827s34s15850551

- RosenstockIMStrecherVJBeckerMHSocial learning theory and the Health Belief ModelHealth Educ Q198815175833378902

- RoterDLHallJAWhy physician gender matters in shaping the physician-patient relationshipJ Womens Health19987109379861586

- SabatéEAdherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action2003GenevaWorld Health Organization

- SackettDLSackettDLHaynesRBIntroductionCompliance with therapeutic regimens1976BaltimoreJohns Hopkins University Press16

- SackettDLHaynesRBGibsonESRandomised clinical trial of strategies for improving medication compliance in primary hypertensionLancet197511205748832

- Sanson-FisherRBowmanJArmstrongSFactors affecting nonadherence with antibioticsDiagn Microbiol Infect Dis199215103S109S1617921

- SchweizerRTRovelliMPalmeriDNoncompliance in organ transplant recipientsTransplantation19904937472305467

- SegadorJGil-GuillenVFOrozcoDThe effect of written information on adherence to antibiotic treatment in acute sore throatInt J Antimicrob Agents200526566115961289

- SeniorVMarteauTMWeinmanJSelf-reported adherence to cholesterol-lowering medication in patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia: the role of illness perceptionsCardiovasc Drugs Ther2004184758115770435

- SeoMAMinSKDevelopment of a structural model explaining medication compliance of persons with schizophreniaYonsei Med J2005463314015988803

- ShawEAndersonJGMaloneyMFactors associated with noncompliance of patients taking antihypertensive medicationsHosp Pharm1995302013206710140764

- SharknessCMSnowDAThe patient’s view of hypertension and complianceAm J Prev Med1992814161632999

- SheaSMisraDEhrlichMHCorrelates of nonadherence to hypertension treatment in an inner-city minority populationAm J Public Health1992821607121456334

- SiegalBGreensteinSJCompliance and noncompliance in kidney transplant patients: cues for transplant coordinatorsTranspl Coord199991048

- SireyJABruceMLAlexopoulosGSStigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherencePsychiatr Serv20015216152011726752

- SleathBWurstKLoweryTDrug information sources and antidepressant adherenceCommunity Ment Health J2003393596812908649

- SloanJPSloanMCAn assessment of default and non-compliance in tuberculosis control in PakistanTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg19817571787330927

- SokolMCMcGuiganKAVerbruggeRRImpact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare costMed Care2005435213015908846

- SpagnoliAOstinoGBorgaADDrug compliance and unreported drugs in the elderlyJ Am Geriatr Soc198937619242738281

- SpikmansFJBrugJDovenMMWhy do diabetic patients not attend appointments with their dietitian?J Hum Nutr Diet200316151812753108

- StantonALDeterminants of adherence to medical regimens by hypertensive patientsJ Behav Med198710377943669072

- StewartRBCaranasosGJMedication compliance in the elderlyMed Clin North Am1989731551632682077

- StilleyCSSereikaSMuldoonMFPsychological and cognitive function: predictors of adherence with cholesterol lowering treatmentAnn Behav Med2004271172415026295

- StrombergABrostromADahlstromUFactors influencing patient compliance with therapeutic regimens in chronic heart failure: A critical incident technique analysisHeart Lung1999283344110486450

- SungJCNicholMBVenturiniFFactors affecting patient compliance with antihyperlipidemic medications in an HMO populationAm J Manag Care1998414213010338735

- SvarstadBLShiremanTISweeneyJKUsing drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costsPsychiatr Serv2001528051111376229

- SwettCJrNoonesJFactors associated with premature termination from outpatient treatmentHosp Community Psychiatry198940947512793099

- TebbiCKCummingsKMZevonMACompliance of pediatric and adolescent cancer patientsCancer1986581179843731045

- TebbiCKTreatment compliance in childhood and adolescenceCancer199371344198490895