Abstract

New data have re-established the importance of anticoagulation of patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), both as an adjuvant to reperfusion therapy or in patients ineligible for reperfusion. Recent randomized trials have found newer agents to be superior to conventional unfractionated heparin. This article summarizes current understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of STEMI and provides a comprehensive review of emerging trial data for low molecular weight heparins, anti-factor Xa agents and direct thrombin inhibitors in this setting.

Introduction

The contemporary approach to a patient with ischemic-type chest pain is to categorize them as experiencing an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) with or without ST segment elevation. The assessment of the initial 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is therefore of critical importance as the management strategy is different for each group (CitationAntman et al 2004; CitationBraunwald et al 2002). Prompt identification of patients with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is vital if patients are to benefit from contemporary management strategies. Over the last 3 decades, major advances in our understanding of the pathophysiological processes responsible for STEMI and its sequelae have allowed development of pharmacological therapies to target these different processes. Numerous large well designed randomized controlled trials have guided determination of ever superior management strategies and their increasing utilization has been associated with a corresponding steady decline in death from acute myocardial infarction (MI) (CitationGoldberg et al 2004).

Pathophysiology of STEMI

Complex inflammatory mechanisms are now known to participate in all stages of coronary artery disease, from the initial development of the fatty streak, through progression to advanced atherosclerotic lesions causing angina pectoris, to plaque disruption and thrombus formation. Plaques vulnerable to disruption and rupture are frequently non-obstructive but have a large lipid-rich core and a high macrophage content leading to thinning of the fibrous cap (CitationMoreno et al 1994; CitationDavies 2000; CitationShah 2003). Plaque rupture, which typically occurs at the edge or shoulder region, exposes the lipid core, leading to platelet adhesion and aggregation, activation of the coagulation cascade, and formation of a platelet rich thrombus. A key step in this process is activation of prothrombin to thrombin (factor IIa) which promotes the formation of fibrin, the protein which acts as a scaffold in stable thrombus. The fate of the thrombus then ranges from simple incorporation into the plaque, through subtotal artery occlusion, to fully occlusive thrombus formation (CitationCorti et al 2003), the latter typically presenting clinically as STEMI (CitationDeWood et al 1980).

Reperfusion strategies for STEMI

Where possible, the immediate treatment goal in STEMI is to disperse the thrombus thereby restoring coronary blood flow to the culprit artery (CitationAntman et al 2004) in order to limit infarct size, to preserve left ventricular function, and ultimately, to reduce mortality.

Two decades on from the landmark GISSI trial with streptokinase, fibrinolytic therapy remains the most widely used reperfusion strategy (CitationGruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI) 1986). Second and third generation fibrinolytic agents interact directly with clot-bound plasminogen improving fibrin selectivity and achieve higher rates of early patency although this has translated at most into only a small further reduction in mortality. More important than the fibrinolytic agent used is the time delay from symptom onset to drug administration (CitationFibrinolytic Therapy Trialists’ (FTT) Collaborative Group 1994; CitationBoersma et al 1996) and hence the value of third generation bolus agents which help facilitate pre-hospital use.

Catheter based reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) where available within a reasonable timeframe, may lead to even better reduction in cardiovascular events, except in patients who present very rapidly after symptom onset when both strategies appear to be equivalent (CitationKeeley et al 2003; CitationSteg et al 2003). Primary PCI is associated with a reduced risk of bleeding complications, in particular intracranial hemorrhage (CitationKeeley et al 2003) which typically occurs in approximately 1% of patients treated with a fibrinolytic based regimen. Trials have shown that the adjuvant anticoagulant dose may play a significant role in the risk of intracranial hemorrhage (CitationGiugliano et al 2001).

Adjuvant antiplatelet therapy

The importance of adjuvant aspirin was established in ISIS-2 (CitationISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group 1988) and the value of concurrent clopidogrel in the more recent CLARITY and COMMIT trials (CitationChen et al 2005; CitationSabatine et al 2005). It is likely that their primary benefit is to reduce reocclusion following successful reperfusion (CitationScirica et al 2006). Initial trials of glycoprotein IIbIIIa receptor antagonists in combination with reduced dose fibrinolytic appeared promising, improving early patency and ST resolution (CitationAntman et al 1999). However the large GUSTO V trial found only a small efficacy advantage in selected subgroups which was offset by a significant increase in bleeding risk (CitationGurm et al 2004).

Adjuvant anticoagulant therapy

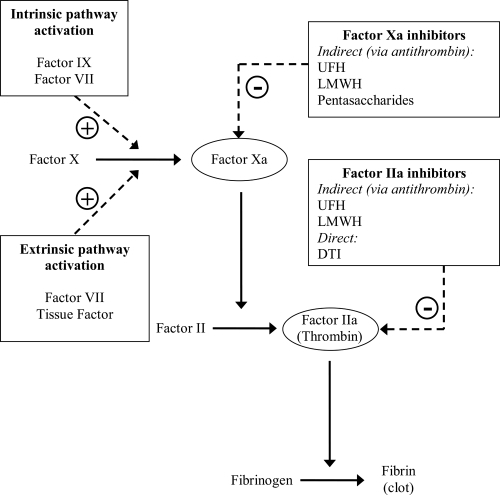

While adjuvant anticoagulant therapy may give a small improvement in patency (CitationRoss et al 2001), like antiplatelet therapy, its main role is in helping to maintain patency after successful reperfusion. Additional potential benefits include prevention of deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and left ventricular thrombus. Current therapy choices include conventional unfractionated heparin (UFH) and newer agents, in particular low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), factor Xa inhibitors and direct thrombin inhibitors. The mechanism of action of these agents is illustrated in .

Figure 1 Interaction of anti-thrombotic agents with coagulation cascade. UFH-antithrombin III complex has approximately equal inhibitory effects on factor Xa and IIa. LMWH-antithrombin III complex has greater relative specificity for factor Xa. Pentasaccharide-antithrombin III complex acts only on factor Xa.

The guidelines mandate the concomitant use of anti-coagulant treatment with either pharmacological or mechanical reperfusion (CitationAntman et al 2004). An area of controversy has existed regarding the need of otherwise for anticoagulation with streptokinase as the latter induces prolonged fibrin depletion. Two meta-analyses, both published in 1996, failed to show evidence of clear benefit with adjuvant UFH (CitationCollins et al 1996; CitationMahaffey et al 1996). However, more recent placebo controlled data have demonstrated benefit for use of concomitant LMWH (CitationSimoons et al 2002; CitationYusuf et al 2005) and factor Xa inhibition (CitationYusuf et al 2006) with streptokinase. Of note there is a paucity of placebo-controlled evidence for use of adjuvant anticoagulation with the fibrin-specific agents, or indeed primary PCI, mainly because of a presumption that anticoagulation use in these settings is clearly indicated.

Unfractionated heparin

Heparin is a heterogeneous mucopolysaccharide which interacts with antithrombin-III greatly increasing its inhibitory effects on thrombin (CitationHirsh and Fuster 1994). The heparin-antithrombin-III complex also has inhibitory effects on factor Xa and other clotting factors. Use of concurrent intravenous heparin has been shown to decrease early thrombin activity, improve culprit artery patency and reduce reocclusion, although the value of delayed subcutaneous (SC) heparin following fibrinolytic therapy is less clear (CitationThe GUSTO Angiographic Investigators 1993; CitationMahaffey et al 1996; CitationGranger et al 1998). A recent meta-analysis failed to show a clear benefit for UFH compared to placebo (CitationEikelboom et al 2005). A major drawback with UFH is the significant variability in therapeutic response which occurs because of its heterogeneous composition and necessitates close monitoring of the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). The typical regimen for use in STEMI is an initial bolus of 60 U/kg (max 4000 U) and continued as an infusion of 12 U/kg/hr (max 1000 U/hr) for 48 hours adjusted to achieve an aPTT of 50–70 seconds. It is notoriously difficult to achieve and maintain the aPTT within this target range, and under-treatment is a significant problem. In the TIMI 9B trial only approximately one third of patients had an aPTT within the target range at any given time, with between 25%–52% having sub-therapeutic levels (CitationAntman et al 1996). Ensuring that the aPTT does not rise above 70 seconds is of vital importance because, once exceeded, the absolute risk of intracranial hemorrhage rises in direct proportion to the aPTT (CitationGranger et al 1996). UFH can also give rise to an immunologically mediated thrombocytopenia known as heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) which is rare but potentially life threatening. These drawbacks, together with the requirement for continuous intravenous (IV) administration, make UFH a less than ideal anticoagulant agent.

Low molecular weight heparin

LMWHs are approximately one third of the molecular weight of UFH, conferring greater bioavailability following subcutaneous administration (CitationAntman 2001). Weight adjusted SC bolus dosing leads to stable and reliable anticoagulation without the need for monitoring, meaning they are much more convenient to administer in clinical practice. As well as improving bioavailability, once binding to antithrombin-III occurs, greater relative specificity for factor Xa is provided when compared to UFH, producing enhanced blockade of the coagulation cascade upstream of thrombin generation. The ratio of inhibition of factor Xa:IIa varies between agents (for enoxaparin the ratio is 3:1) (CitationArmstrong 1997). HIT is less common with LMWH compared to UFH (CitationWarkentin et al 1995), but it is important to remember that, because LMWHs are made by depolymerisation of UFH, they can still give rise to this condition.

Placebo controlled studies with LMWH have confirmed the importance of an adjuvant anticoagulant strategy. The AMI-SK study of 496 streptokinase treated MI patients showed that adjuvant enoxaparin compared with placebo improved early patency by 22%, improved early ST-segment resolution and was associated with a 36% reduction in the composite of death, reinfarction and recurrent angina (CitationSimoons et al 2002). The CREATE trial compared the LMWH reviparin with placebo in 15570 patients with STEMI (CitationYusuf et al 2005), of whom 73% received fibrinolytic therapy and 6.1% underwent primary PCI, the remainder being treated conservatively. Reviparin significantly reduced the composite endpoint of death, reinfarction and stroke although those receiving fibrinolytic therapy had an increased the risk of major bleeding including intracranial hemorrhage (0.4% vs 0.1% for reviparin and placebo groups respectively).

Enoxaparin has been extensively compared to UFH following fibrinolytic therapy for acute MI (see ). Following early studies (Baird et al and HART II), the ASSENT-3 trial randomized over 6000 patients receiving tenecteplase to full-dose tenecteplase and enoxaparin, half-dose tenecteplase with weight-adjusted low-dose UFH and a 12-hour abciximab infusion, or full-dose tenecteplase with 48 hours UFH (CitationAssessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT)-3 Investigators 2001). Administration of enoxaparin with full dose tenecteplase led to significant reductions in 30-day mortality, in-hospital reinfarction and in-hospital recurrent ischemia compared with UFH, with no significant increase in overall bleeding.

Table 1 Important randomized controlled trials comparing LMWH with UFH in patients treated with fibrinolytic therapy for STEMI

However, the ASSENT-3 PLUS study of over 1600 pre-hospital patients (CitationWallentin et al 2003) showed an excess of intracranial hemorrhage with enoxaparin in patients >75 years, suggesting that a dose reduction was needed in this age group. The pivotal 20475 patient ExTRACT-TIMI 25 study (CitationAntman et al 2006) thus compared UFH (standard bolus and 48 hour infusion) with a modified enoxaparin regimen – standard 30 mg IV bolus then 1 mg/kg bd until hospital discharge, but reduced dose in patients ≥75 yrs (no initial IV bolus, SC dose reduced to 0.75 mg/kg) and a reduced frequency (once a day) in patients with impaired renal function. Median treatment duration with UFH was 2.0 days (interquartile range 2.0–2.2) and with enoxaparin was 7.0 days (interquartile range 4.5–7.5). Enoxaparin was associated with a 17% reduction in death or MI (9.9% vs 12%; p < 0.001), excess major bleeding (2.1% vs 1.4%) but no excess of intra-cranial hemorrhage (0.8% vs 0.7%; p = 0.14) and overall net clinical benefit. Although it may be argued that ExTRACT was a comparison of treatment durations rather than drugs, even at 48 hours, the composite of death, MI and urgent revascularization was significantly reduced with enoxaparin treatment (6.1% vs 5.3%; p = 0.02). Based on ExTRACT trial data, the Food and Drug Administation have formally approved enoxaparin for use in ST elevation MI.

A planned substudy of the ExTRACT trial (ExTRACT-PCI) evaluated whether enoxaparin was superior to UFH in those STEMI patients (almost a quarter of the total study cohort) who received thrombolytic therapy and subsequently underwent PCI within 30 days (CitationGibson et al 2007). By 30 days, patients randomised to enoxaparin showed a 23% relative reduction in death or MI compared to UFH (10.7% vs. 13.8%; p = 0.001) without a significant difference in the risk of major bleeding. Almost one half of the patients in this substudy underwent PCI while still receiving blinded study drug. Again, for this cohort, a reduction in 30 day death or MI risk was seen in the enoxaparin group compared to the UFH group (13.0% vs 16.7%; p = 0.013) without an increased risk of major bleeding.

Pentasaccharides

Pentasaccharides are manufactured to have a chemical structure similar to the antithrombin-III binding domain (active site) of heparin. Binding of pentasaccharide to antithrombin-III induces conformational changes leading to selective and potent inhibition of factor Xa resulting in greatly reduced thrombin generation (CitationCoussement et al 2001). Unlike UFH and LMWH there is no inhibitory effect on thrombin molecule itself. Pentasaccharides, such as fondaparinux, can therefore be considered as synthetic, highly selective, indirect inhibitors of factor Xa. Potential advantages of fondaparinux include 100% bioavailability after subcutaneous injection, a long half-life of 15–18 hours allowing for once daily administration, predictable anticoagulant effect with no requirement for monitoring, and no cross-reactivity with antibodies associated with HIT (CitationWalenga et al 1997; CitationEfird and Kockler 2006). Also, selective and potent targeting of an upstream step in the coagulation cascade theoretically achieves superior anticoagulation as inhibition of one molecule of factor Xa reduces the downstream production of many molecules of thrombin (CitationAntman 2001). summarizes the significant results from the 2 clinical end-point trials which investigate fondaparinux use in STEMI patients.

Table 2 Clinical endpoint trials for the use of fondaparinux in STEMI patients

The PENTALYSE study compared 5–7 days fondaparinux (4 mg, 8 mg, or 12 mg, initial dose IV then SC daily) with 48–72 hours UFH in 326 STEMI patients being treated with aspirin and alteplase (CitationCoussement et al 2001). There was no difference in early artery patency determined by 90 minute coronary angiography. Patients who did not have coronary intervention during the treatment period, showed a trend to less reocclusion with fondaparinux (repeat angiography day 5–7). PENTALYSE reported a trend to increased instrumental bleeding but no overall increase in hemorrhage.

The large multi-centre OASIS 6 trial (CitationYusuf et al 2006) is the first large scale trial to report on the efficacy and safety of fondaparinux in the setting of STEMI and therefore provides an extremely important extension of available evidence. It enrolled 12092 STEMI patients from 41 countries and randomized them in a complex design to fondaparinux (2.5 mg once daily for up to 8 days) or usual care which was defined as either placebo alone where UFH was not indicated (stratum 1, n = 5658), or UFH for up to 48 hours followed by placebo for up to 8 days in patients with an indication for UFH (stratum 2, n = 6434). The initial dose of fondaparinux was SC in stratum 1 and IV in stratum 2. The decision as to whether UFH was indicated was not predefined but based on the investigator’s judgment. As with ExTRACT, it is important to note that stratum 2 was not only comparing 2 anticoagulants, but also 2 anticoagulation strategies. UFH was given for up to 48 hours only, while fondaparinux was given for up to 8 days. Fibrinolytic therapy was used in 45% of the patients (78.0% in stratum 1 and 15.9% in stratum 2), with streptokinase being the most commonly used (approximately 73%). Primary PCI was undertaken in 28.9% (0.2% in stratum 1 and 53.2% in stratum 2). Almost a quarter of patients (23.7%) did not receive any reperfusion therapy. The primary endpoint (death/re-MI) in stratum 1 patients was significantly reduced by fondaparinux compared with placebo (11.2 vs 14.0; HR 0.79 [95% CI 0.68–0.92]). This adds to existing evidence (from AMI-SK and CREATE trials) confirming adjuvant antithrombotic therapy is indicated along with fibrinolytic therapy, including streptokinase. In stratum 2 patients, there was no significant reduction in the primary endpoint for fondaparinux compared with UFH (8.3 vs 8.7; HR 0.96 [95% CI 0.81–1.13]). Also of note, in patients undergoing primary PCI there was an increase in complications with fondaparinux compared with UFH including guide catheter thrombosis, abrupt coronary artery closure, new angiographic thrombus, or no reflow. An interim protocol modification advising additional UFH in fondaparinux patients undergoing acute PCI was thus required.

Surprisingly, lower rates were observed for severe hemorrhage (44 vs 28; p = 0.06) and for major bleeds (57 vs 39; p = 0.07) with fondaparinux compared with placebo in stratum 1. This is in contrast to the CREATE trial which demonstrated a significant excess of life-threatening bleeding in patients who received reviparin compared to placebo. The reason for a reduction in major bleeding is not well understood – some suggesting it may be a consequence of better clinical outcome and/or reduced need for urgent revascularization. In stratum 2, the rates of severe and major bleeds were similar in the 2 groups.

Several conclusions can be drawn from the OASIS-6 trial. There is clear benefit for fondaparinux in STEMI patients without an indication for UFH, where it is as safe as no anticoagulation. In conservatively managed STEMI patients with an indication for UFH who receive fibrinolytic therapy, fondaparinux is at least as effective and as safe as UFH. However, the use of fondaparinux as the sole anticoagulant for STEMI patients treated with primary PCI is associated with an increased risk of thrombotic complications, and thus pre-treatment with UFH before PCI is required.

Direct thrombin inhibitors

Unlike UFH, direct thrombin (factor IIa) inhibitors inactivate clot bound thrombin and prevent thrombin induced platelet aggregation. In the large GUSTO IIb trial (CitationMetz et al 1998) 2274 patients treated with fibrinolytic therapy for STEMI were randomly assigned to the direct thrombin inhibitor hirudin or UFH. In patients receiving streptokinase, hirudin compared with UFH was associated with a reduction in 30 day death/re-MI (8.6% vs 14.4%; p = 0.004) although no difference was seen in patients treated with tissue-type plasminogen activator (see ). In the HIT 4 study (CitationNeuhaus et al 1999), 1208 patients with STEMI were treated with aspirin and streptokinase and randomized to receive recombinant hirudin or heparin. A trend to earlier ST resolution was seen, but no difference in reinfarction, mortality or bleeding rates.

Table 3 Evidence for direct thrombin inhibitors as adjuvant anticoagulation for patients with STEMI receiving fibrinolytic therapy

A similar direct thrombin inhibitor, bivalirudin, showed improved early patency compared with UFH as an adjunct to streptokinase in the HERO study (CitationWhite et al 1997). In the large 17073 patient HERO-2 study, bivalirudin as an adjunct to streptokinase did not reduce mortality at 30 days compared with UFH, but did reduce the rate of re-infarction within 4 days by 30% (CitationWhite et al 2001). It is noteworthy that, unlike ExTRACT and OASIS-6, this trial compared identical treatment durations of the anticoagulants under investigation (48 hour infusion). The advantage of bivalirudin over UFH in terms of reduced reinfarction came at the cost of a relatively small increase in moderate bleeding (1.4% vs 1.1%; p = 0.05). There was no significant difference in the risk of severe bleeding. This finding of increased moderate bleeding is not consistent with previous trials (CitationKong et al 1999). Again, more recently, bivalirudin has been associated with reduced bleeding compared with UFH plus antiplatelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during early PCI for non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes (CitationStone et al 2006). It is currently being evaluated in the HORIZONS primary PCI STEMI trial, which is comparing bivalirudin to heparin plus glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor.

Summary and conclusions

The role of UFH in STEMI, particularly as an adjunct to fibrinolytic therapy, is being strongly challenged by the wealth of data surrounding newer anticoagulants including LMWH, factor Xa inhibitors and direct thrombin inhibitors. The evidence base is strongest for the LMWH enoxaparin where meta-analyses of multiple trials and the large ExTRACT trial have confirmed that enoxaparin (dose-adjusted for weight, renal function and age ≥75) compared with UFH, results in significant net clinical benefit. The recently published substudy of ExTRACT demonstrated superiority of enoxaparin over UFH in the patients who underwent PCI within 30 days of fibrinolytic therapy for STEMI, without a significant difference in bleeding. The results of this study also suggest that for patients commenced on adjuvant enoxaparin after fibrinolytic therapy there is no need to switch to UFH if they proceed to PCI during the period of anticoagulation. Thus while based on current evidence, enoxaparin may be considered the anticoagulant of choice in STEMI, the factor Xa inhibitor fondaparinux suggests the intriguing possibility of further reduction in bleeding risk without loss of efficacy. OASIS-6 has provided important data on ‘real-world’ use of fondaparinux, but because of the heterogeneous trial population and dependence on local investigator discretion to decide on the appropriateness of anticoagulant therapy, drawing firm conclusions for contemporary practice is difficult. Additionally, given the increasing provision of early PCI after successful fibrinolysis or rescue PCI after failed fibrinolytic therapy, the excess of guide catheter thrombosis is an apparent limitation. While the direct thrombin inhibitor bivalirudin was associated with increased bleeding compared with UFH in HERO-2, more recent trials have focused on its potential as a substitute for UFH plus IIbIIIa inhibitors (and hence potential for reduced bleeding) during PCI. The ongoing HORIZONS trial will provide important data regarding bivalirudin's role in primary PCI. However as most STEMI patients continue to receive a primary fibrinolytic strategy, a head-to-head comparison of fondaparinux and bivalirudin with dose adjusted enoxaparin in a clearly-defined, fibrinolytic-treated population is eagerly awaited.

References

- AntmanEMMorrowDAMcCabeCHEnoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin with fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarctionThe New England Journal of Medicine200635414778816537665

- AntmanEMAnbeDTArmstrongPWACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction – executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction)Circulation200411058863615289388

- AntmanEMLouwerenburgHWBaarsHFEnoxaparin as adjunctive antithrombin therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: results of the ENTIRE-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 23 TrialCirculation20021051642911940541

- AntmanEMThe search for replacements for unfractionated heparinCirculation200110323101411342482

- AntmanEMGiuglianoRPGibsonCMAbciximab facilitates the rate and extent of thrombolysis: results of the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 14 trial. The TIMI 14 InvestigatorsCirculation19999927203210351964

- AntmanEMTIMI 9B InvestigatorsHirudin in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Thrombolysis and Thrombin Inhibition in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 9B TrialCirculation199694911218790025

- ArmstrongPWHeparin in acute coronary disease – requiem for a heavyweight?The New England Journal of Medicine199733749249250854

- Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT)-3 InvestigatorsEfficacy and safety of tenecteplase in combination with enoxaparin, abciximab, or unfractionated heparin: the ASSENT-3 randomised trial in acute myocardial infarctionLancet20013586051311530146

- BairdSHMenownIBMcBrideSJRandomized comparison of enoxaparin with unfractionated heparin following fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarctionEuropean Heart Journal2002236273211969277

- BoersmaEMaasACDeckersJWEarly thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: reappraisal of the golden hourLancet199634877158813982

- BraunwaldEAntmanEMBeasleyJWACC/AHA guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction--2002: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina)Circulation2002106189390012356647

- ChenZMJiangLXChenYPAddition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trialLancet200536616072116271642

- CollinsRMacMahonSFlatherMClinical effects of anticoagulant therapy in suspected acute myocardial infarction: systematic overview of randomised trialsBritish Medical Journal199631365298811758

- CortiRFusterVBadimonJJPathogenetic concepts of acute coronary syndromesJournal of the American College of Cardiology2003414 Suppl S7S14S12644335

- CoussementPKBassandJPConvensCA synthetic factor-Xa inhibitor (ORG31540/SR9017A) as an adjunct to fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction. The PENTALYSE studyEuropean Heart Journal20012217162411511121

- DaviesMJThe pathophysiology of acute coronary syndromesHeart200083361610677422

- DeWoodMASporesJNotskeRPrevalence of total coronary occlusion during the early hours of transmural myocardial infarctionThe New England Journal of Medicine19803038979027412821

- EfirdLEKocklerDRFondaparinux for Thromboembolic Treatment and Prophylaxis of Heparin-Induced ThrombocytopeniaThe Annals of Pharmacotherapy2006401383716788093

- EikelboomJWQuinlanDJMehtaSRUnfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin as adjuncts to thrombolysis in aspirin-treated patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of the randomized trialsCirculation200511238556716344381

- Fibrinolytic Therapy Trialists’ (FTT) Collaborative GroupIndications for fibrinolytic therapy in suspected acute myocardial infarction: collaborative overview of early mortality and major morbidity results from all randomised trials of more than 1000 patientsLancet1994343311227905143

- GibsonCMMurphySAMontalescotGPercutaneous coronary intervention in patients receiving enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin after fibrinolytic therapy for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the ExTRACT-TIMI 25 trialJournal of the American College of Cardiology20074922384617560287

- GiuglianoRPMcCabeCHAntmanEMLower-dose heparin with fibrinolysis is associated with lower rates of intracranial hemorrhageAmerican Heart Journal20011417425011320361

- GoldbergRJSpencerFAYarzebskiJA 25-year perspective into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (the Worcester Heart Attack Study)The American Journal of Cardiology2004941373815566906

- GrangerCBBeckerRTracyRPThrombin generation, inhibition and clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic therapy and heparin: results from the GUSTO-I Trial. GUSTO-I Hemostasis Substudy Group. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Coronary ArteriesJournal of the American College of Cardiology1998314975059502626

- GrangerCBHirschJCaliffRMActivated partial thromboplastin time and outcome after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: results from the GUSTO-I trialCirculation19969387088598077

- Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Streptochinasi nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)Effectiveness of intravenous thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarctionLancet198613974022868337

- GurmHSLincoffAMLeeDOutcome of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in diabetics treated with fibrinolytic or combination reduced fibrinolytic therapy and platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition: lessons from the GUSTO V trialJournal of the American College of Cardiology200443542814975461

- HirshJFusterVGuide to anticoagulant therapy. Part 1: Heparin. American Heart AssociationCirculation1994891449688124829

- ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative GroupRandomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17,187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction: ISIS-2Lancet19882349602899772

- KeeleyECBouraJAGrinesCLPrimary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trialsLancet2003361132012517460

- KongDFTopolEJBittlJAClinical outcomes of bivalirudin for ischemic heart diseaseCirculation199910020495310562259

- MahaffeyKWGrangerCBCollinsROverview of randomized trials of intravenous heparin in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic therapyThe American Journal of Cardiology19967755168610601

- MetzBKWhiteHDGrangerCBRandomized comparison of direct thrombin inhibition versus heparin in conjunction with fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: results from the GUSTO-IIb Trial. Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes (GUSTO-IIb) InvestigatorsJournal of the American College of Cardiology199831149389626825

- MorenoPRFalkEPalaciosIFMacrophage infiltration in acute coronary syndromes. Implications for plaque ruptureCirculation19949077588044947

- NeuhausKLMolhoekGPZeymerURecombinant hirudin (lepirudin) for the improvement of thrombolysis with streptokinase in patients with acute myocardial infarction: results of the HIT-4 trialJournal of the American College of Cardiology1999349667310520777

- RossAMMolhoekPLunderganCRandomized comparison of enoxaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, with unfractionated heparin adjunctive to recombinant tissue plasminogen activator thrombolysis and aspirin: second trial of Heparin and Aspirin Reperfusion Therapy (HART II)Circulation20011046485211489769

- SabatineMSCannonCPGibsonCMAddition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevationThe New England Journal of Medicine200535211798915758000

- SciricaBMSabatineMSMorrowDAThe role of clopidogrel in early and sustained arterial patency after fibrinolysis for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the ECG CLARITY-TIMI 28 StudyJournal of the American College of Cardiology200648374216814646

- ShahPKMechanisms of plaque vulnerability and ruptureJournal of the American College of Cardiology2003414 Suppl S15S22S12644336

- SimoonsMKrzeminska-PakulaMAlonsoAImproved reperfusion and clinical outcome with enoxaparin as an adjunct to streptokinase thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. The AMI-SK studyEuropean Heart Journal20022312829012175665

- StegPGBonnefoyEChabaudSImpact of time to treatment on mortality after prehospital fibrinolysis or primary angioplasty: data from the CAPTIM randomized clinical trialCirculation20031082851614623806

- StoneGWMcLaurinBTCoxDABivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromesThe New England Journal of Medicine200635522031617124018

- The GUSTO Angiographic InvestigatorsThe effects of tissue plasminogen activator, streptokinase, or both on coronary-artery patency, ventricular function, and survival after acute myocardial infarctionThe New England Journal of Medicine19933291615228232430

- WalengaJMJeskeWPBaraLBiochemical and pharmacologic rationale for the development of a synthetic heparin pentasaccharideThrombosis Research1997861369172284

- WallentinLGoldsteinPArmstrongPWEfficacy and safety of tenecteplase in combination with the low-molecular-weight heparin enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin in the prehospital setting: the Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT)-3 PLUS randomized trial in acute myocardial infarctionCirculation20031081354212847070

- WarkentinTELevineMNHirshJHeparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients treated with low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparinThe New England Journal of Medicine1995332133057715641

- WhiteHHirulog and Early Reperfusion or Occlusion (HERO)-2 Trial InvestigatorsThrombin-specific anticoagulation with bivalirudin versus heparin in patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: the HERO-2 randomised trialLancet200135818556311741625

- WhiteHDAylwardPEFreyMJRandomized, double-blind comparison of hirulog versus heparin in patients receiving streptokinase and aspirin for acute myocardial infarction (HERO). Hirulog Early Reperfusion/Occlusion (HERO) Trial InvestigatorsCirculation1997962155619337184

- YusufSMehtaSRChrolaviciusSEffects of fondaparinux on mortality and reinfarction in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the OASIS-6 randomized trialThe Journal of the American Medical Association2006295151930

- YusufSMehtaSRXieCEffects of reviparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, on mortality, reinfarction, and strokes in patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting with ST-segment elevationThe Journal of the American Medical Association200529342735