?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Nebivolol is a highly selective beta1-adrenergic blocker that also enhances nitric oxide bioavailability via the L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway, leading to vasodilation and decreased peripheral vascular resistance. It is marketed in Europe for the treatment of hypertension and heart failure and is currently being reviewed for use in the US by the Food and Drug Administration. Nebivolol appears to be well tolerated with an adverse event profile that is at least similar, if not better, than that of other beta-adrenergic blockers. Studies suggest that long-term therapy with nebivolol improves left ventricular function, exercise capacity, and clinical endpoints of death and cardiovascular hospital admissions in patients with stable heart failure. To date, it is one of the only beta-adrenergic blockers that have been exclusively studied in elderly patients. Additionally, the unique mechanism of action of nebivolol makes it a promising agent for treatment of chronic heart failure in high-risk patient populations, such as African Americans. This article will review the pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic properties of nebivolol as well as clinical studies assessing its efficacy for the treatment of heart failure.

Introduction

The pathophysiology of chronic heart failure involves a process of left ventricular remodeling, whereby molecular changes occur within the myocardium in response to mechanical stresses induced by underlying diseases, such as hypertension, ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathies, and valvular abnormalities. Structural changes that occur, including left ventricular hypertrophy and/or dilation, typically result in decreased left ventricular diastolic or systolic function (CitationJessup and Brozena 2003; CitationOpie et al 2006). This remodeling process is accelerated by the activation of a number of endogenous neurohormonal systems including, but not limited to, the sympathetic nervous system, which releases high levels of the adrenergic substance norepinephrine and stimulates the release of renin in the kidney (CitationJessup and Brozena 2003; CitationHunt et al 2005). The resultant increase in heart rate, contractility, peripheral vasoconstriction, and blood volume, as well as the direct toxic effects of norepinephrine on myocytes, increases cardiac workload and further impairs cardiac performance (CitationHunt et al 2005). Beta-adrenergic blockers, by suppressing the deleterious effects of norepinephrine have become routine therapy for the treatment of chronic heart failure (CitationHunt et al 2005; CitationMcMurray et al 2005; CitationSwedberg et al 2005).

The benefits of beta-adrenergic blockers in the treatment of chronic heart failure are exclusive to those agents that have demonstrated a survival benefit in clinical trials and should not, therefore, be considered a class effect. In the US, three beta-adrenergic blockers are currently available for use in chronic heart failure based on evidence demonstrating a survival benefit: carvedilol, which blocks alpha1-, beta1-, and beta2-receptors; and sustained-release metoprolol succinate and bisoprolol, which both selectively block beta1-receptors (CitationPacker et al 1996; CitationCIBIS II Investigators 1999; CitationHjalmarson et al 1999; CitationPacker et al 2001; CitationHunt et al 2005). Nebivolol is a third-generation beta-adrenergic blocker that has been marketed and used in Europe for the treatment of hypertension and heart failure (CitationA. Menarini Pharmaceuticals 2005; CitationMcMurray et al 2005). It is currently under FDA review in the US for hypertension and it is anticipated that an indication for heart failure will be pursued in the near future.

Pharmacology

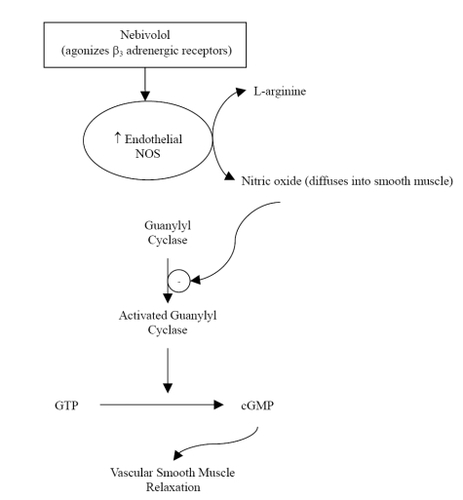

Nebivolol is a racemic mixture containing equal amounts of 2 isomers, d-nebivolol and l-nebivolol. D-nebivolol provides selective beta1-adrenergic receptor blockade while both d- and l-nebivolol cause nitricoxide-induced vasodilation (CitationCockcroft et al 1995; CitationVan Neuten 1998). Nebivolol, which has no intrinsic sympathomimetic activity, is considered a highly selective beta1-adrenergic blocker due to its 321-fold higher affinity for human cardiac beta1-receptors versus beta2-receptors; it is also more selective for beta1-receptors than any other agent in its class (CitationBrixius et al 2001; CitationBristow et al 2005). Unlike other beta-adrenergic blockers with vasodilatory properties, nebivolol has no alpha-blocking effects (CitationBowman et al 1994; CitationVan Bortel et al 1997). The vasodilatory action of nebivolol is mediated via the L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway, whereby nitric oxide production by endothelial nitric oxide synthases is enhanced (CitationBowman et al 1994; CitationCockcroft et al 1995; CitationIgnarro 2004). There is evidence to suggest that this mechanism is in part due to agonist activity of nebivolol at endothelial beta3-adrenergic receptors () (CitationGauthier et al 1998; CitationGosgnach et al 2001; CitationDessy et al 2005). This was recently tested and confirmed by Dessy and colleagues who established that nebivolol relaxation of human coronary microarteries that were precontracted with endothelin-1 was significantly inhibited by bupranolol, a beta1,2,3-receptor blocker, but not significantly inhibited by nadolol, a beta1,2-receptor blocker (CitationDessy et al 2005). Nitric oxide bioavailability may also be augmented with nebivolol treatment due to decreased inactivation by reactive oxygen entities (CitationJanssen et al 2001; CitationCominacini et al 2003; CitationPasini et al 2005).

Figure 1 The effect of nebivolol on the L-arginine-nitric-oxide pathway. Reprinted with permission CitationVeverka A, Nuzum DS, Jolly JL. 2006. Nebivolol: a third-generation β-adrenergic blocker. Ann Pharmacother, 40:1353–60. Copyright ©2006. Harvey Whitney Books.

This unique mechanism of nebivolol is particularly important due to the critical role of nitric oxide in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure. In addition to causing vasodilation, nitric oxide also inhibits platelet aggregation, atherosclerosis and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (CitationMason 2006). When endothelial dysfunction occurs, nitric oxide production and function is impaired, leading to increased peripheral resistance and a pro-thrombotic and pro-atherogenic environment (CitationPanza et al 1990; CitationMoncada and Higgs 1993; CitationKinlay et al 2001; CitationMason 2006). To distinguish the vasodilatory action of nebivolol from other beta-adrenergic blockers that selectively inhibit beta1-receptors, Lekakis and colleagues tested the effect of nebivolol and atenolol on flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery (CitationLekakis et al 2005). Following 4 weeks of drug therapy, patients treated with nebivolol had significantly increased flow-mediated dilation, while those treated with atenolol had no change compared to baseline.

The increased bioavailability of nitric oxide with nebivolol treatment may prove to be particularly useful for treating African American patients with cardiovascular disease. It has been proposed that decreased endothelial nitric oxide bioavailability may be more prevalent as an underlying cause of cardiovascular disease in this patient subgroup, and previous studies of African American patients with heart failure have shown a favorable response to therapies that increase nitric oxide availability (CitationTaylor et al 2004). The mechanism of decreased nitric oxide bioavailability in African American patients may be due to oxidative stress caused by upregulation of NAD(P)H-dependent oxidases and subsequent increases in production of superoxide ().

can react with nitric oxide, decreasing its bioavailability and increasing production of the oxidant peroxynitrite (ONOO−) (CitationKalinowski et al 2004). Mason and colleagues compared the activity of nebivolol and atenolol on nitric oxide release from endothelial cells of age-matched African American and Caucasian donors with comparable cardiovascular risk histories (CitationMason et al 2005). Levels of nitric oxide, as well as ONOO− and

, the primary components of nitroxidative and oxidative stress in the vascular system, were measured to assess endothelial function. At baseline, release of nitric oxide was 5 times slower, and release of both ONOO− and

was 2–4 times faster in African Americans compared to Caucasians. While atenolol had no effect on nitric oxide, ONOO−, and

levels in either white or black patients, nebivolol treatment increased nitric oxide and reduced ONOO− and

levels in African Americans to similar levels documented in Caucasian patients.

Pharmacokinetics and drug interactions

summarizes the general pharmacokinetic properties of nebivolol and other beta-adrenergic blockers typically used in the management of heart failure (CitationFrishman and Alwarshetty 2002; CitationEon Labs, Inc. 2004; CitationAstraZeneca LP 2006; CitationGlaxoSmithKline 2007). Nebivolol is rapidly absorbed following oral administration, reaching peak plasma concentrations within 0.5–4 hours after a dose (CitationSule and Frishman 2006). Food has a minimal impact on absorption and therefore nebivolol may be taken without regard to meals (CitationShaw et al 2003a). Nebivolol is extensively metabolized via hydroxylation in the hepatic system to active and inactive metabolites. The oral bioavailability of nebivolol is dependent on cytochrome P450 2D6 genetic polymorphism and so ranges from 12% in extensive metabolizers to 96% in poor metabolizers. Similarly, the half-life of nebivolol is approximately 10 hours in extensive metabolizers but can be prolonged up to 30–50 hours in poor metabolizers (CitationVan Peer et al 1991; CitationA. Menarini Pharmaceuticals 2005). Despite genetic differences in metabolism of nebivolol, the clinical response to the drug appears to be similar (CitationLefebvre et al 2006). Nebivolol displays linear kinetics across a dose range of 2.5–20 mg, demonstrated by dose-proportional changes in maximum concentrations (Cmax) and area under the drug concentration curve (AUC) (CitationShaw 2003b). The average volume of distribution of nebivolol is 10 L/kg and this does not appear to be affected by patient weight (CitationCheymol et al 1997). Less than 1% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine and so adjustments of doses in patients with chronic renal failure are unnecessary (CitationA. Menarini Pharmaceuticals 2005).

Table 1 Pharmacokinetic characteristics of beta-adrenergic blockers used in the management of heart failure

Nebivolol is highly protein bound intravascularly, predominately to albumin. Studies assessing drug interactions with nebivolol in healthy volunteers have found no significant interactions with spironolactone, hydrochlorothiazide, digoxin, warfarin, losartan, and ramipril (CitationLawrence et al 2003; CitationMorton et al 2003, Citation2005; CitationLawrence et al 2005a, Citationb, Citationc). Co-administration with cimetidine, a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 3A4, increased the bioavailability of nebivolol, however this interaction did not influence the extent to which nebivolol reduced heart rate and blood pressure (CitationKamali et al 1997). Similarly, fluoxetine, a cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibitor, resulted in peak plasma concentrations of nebivolol that were three times higher than normal (CitationShaw 2005). Although the clinical impact of cytochrome P450 drug interactions with nebivolol is unclear, caution should be exercised when inhibitors or inducers of 2D6 and 3A4 are used in conjunction with this agent. At this time, it is also unknown whether nebivolol is a substrate of p-glycoprotein and if there is a risk of drug interactions at this protein.

Clinical studies

Earlier studies assessing the utility of nebivolol in chronic heart failure were limited by small patient populations. These studies did suggest, however, that nebivolol would improve left ventricular function and mechanics; improve patient functional capacity assessed by New York heart association (NYHA) classification; and would at least have a stabilizing effect on exercise capacity (CitationUhlir et al 1997; CitationBrehm et al 2002). More recently, the ENECA (efficacy of nebivolol in the treatment of elderly patients with chronic heart failure as add-on therapy to ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, diuretics, and/or digitalis) study performed by Edes and colleagues evaluated whether nebivolol therapy improves left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) compared with placebo in 260 patients with chronic heart failure (CitationEdes et al 2005). The study design also included a secondary endpoint to assess the safety and tolerability of nebivolol in elderly patients, defined in the study as age greater than 65. In addition to the age requirement, patients qualified for enrollment in the study if they met the following criteria: NYHA class II, III, or IV; LVEF less than or equal to 35%; stable clinical status; and stable therapy for at least 2 weeks prior to randomization with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and/or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), diuretics, and/or digitalis. Patients were randomized to therapy with nebivolol 1.25 mg daily, titrated to a target dose of 10 mg, or placebo and followed for a period of 8 months. Intention to treat analysis showed that nebivolol therapy significantly increased LVEF compared with placebo (improvement of 6.51 ± 9.15% vs 3.97 ± 9.2% from baseline, respectively; p = 0.027), and this was consistent across all subgroups examined. Quality of life and changes in NYHA functional class were not significantly improved with nebivolol therapy in this trial. While nebivolol was generally well tolerated in this elderly population and did not result in an increased number of patients experiencing adverse events compared with placebo (81 vs 78, respectively; p = 0899), drug-related adverse events were more commonly reported with nebivolol vs placebo (40 vs 14; p < 0.0001). The most frequent of these were hypotension, bradycardia, and dizziness. Despite proving in the ENECA study that nebivolol is superior to placebo in improving surrogate endpoints of chronic heart failure, this study was underpowered to assess the effect of nebivolol on clinical endpoints such as overall survival, cardiovascular death, or need for cardiovascular hospital admission.

Subsequent to the ENECA study, Flather and colleagues published the results of the SENIORS (study of the effects of nebivolol intervention on outcomes and rehospitalization in seniors with heart failure) trial (CitationFlather et al 2005). This was the first and is the only randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to date assessing the benefit of nebivolol therapy on morbidity and mortality. The trial enrolled 2135 elderly patients, defined as 70 years of age or older, with a clinical history of heart failure, defined as a documented LVEF less than or equal to 35% within the previous 6 months or hospitalization with a discharge diagnosis of chronic heart failure within the previous 12 months. Patients were enrolled provided they were not currently receiving therapy with a beta-adrenergic blocker or had a contraindication to treatment. The primary outcome of the SENIORS trial was a composite of all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospital admission. In the nebivolol arm, doses of 1.25 mg daily were initiated and titrated over a 16 week period to a target dose of 10 mg once daily. Over a mean treatment period of 21 months, 31.1% of patients in the nebivolol group reached the primary endpoint compared with 35.3% in the placebo group (hazard ration [HR] 0.86, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.74–0.99, p = 0.039). These results imply that 24 patients with chronic heart failure would need to be treated with nebivolol for approximately 2 years to prevent one death or cardiovascular hospital admission. Of note, this benefit was observed as early as 6 months and was independent of baseline therapy with diuretics, ACEIs, digoxin, and/or spironolactone which were used by approximately 85%, 82%, 40%, and 38% of patients enrolled, respectively. Subgroup analysis determined that nebivolol was efficacious regardless of age, gender, ejection fraction, diabetes, or prior myocardial infarction. At the present time, the SENIORS trial is the only assessment of beta-adrenergic blocker therapy in an elderly population with chronic heart failure. This may be of particular importance in clinical practice since the prevalence of heart failure increases with age, from 2% to 3% at age 65 years to greater than 80% in patients aged 80 years and above (CitationHunt et al 2005). Additionally, treatment of elderly patients with beta-adrenergic blockers can be more challenging due to desensitization of beta-adrenergic receptors and variable pharmacokinetic responses that occur with age (potentially decreased absorption, metabolism and excretion) (CitationTregaskis and McDevitt 1990; CitationFrishman and Alwarshetty 2002). While adverse outcomes have been documented when standard therapy for heart failure is insufficient, it is important to individualize therapy for each individual patient (CitationKomajda et al 2005).

There are very few head-to-head comparisons of beta-adrenergic blockers for the treatment of chronic heart failure. Nebivolol has been compared with carvedilol in two small trials. Patrianakos and colleagues assessed the effects of carvedilol and nebivolol on left ventricular function and exercise capacity at 3 and 12 months. Seventy-two patients with NYHA class II or III heart failure, specifically non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy documented by a LVEF of less than 45% on echocardiogram within the previous 6 months (CitationPatrianakos et al 2005) were included. Patients were randomized to double-blind therapy with either carvedilol 3.125 mg twice daily or nebivolol 1.25 mg once daily, with titration to carvedilol 25 mg twice daily or nebivolol 5 mg daily as tolerated. Additional requirements for enrollment included stable therapy with an ACEI or ARB for at least 4 weeks prior to randomization with no new drug therapies initiated within 6 weeks prior to randomization. No patients enrolled in the study had received prior treatment with a beta-adrenergic blocker. At 3 and 12 months, both nebivolol and carvedilol caused significant improvements in LVEF compared with baseline. Intergroup comparisons, however, revealed that carvedilol provided a greater change in LVEF than nebivolol at these time points (3 months: absolute improvement of 7.4% vs 4.8%; relative improvement of 32.1% ± 34.9% vs 15.3% ± 15.9%, mean difference −16.7% ± 16.5%, 95% CI −29.9 to −3.4, p = 0.004; 12 months: absolute improvement of 8.8% vs 6.1%; relative improvement of 35.5% ± 31.9% vs 20.7% ± 19.1%, mean difference −14.7% ± 6.4%, 95% CI −27.8 to −1.8, p = 0.02). Both agents significantly decreased left ventricular end-systolic volumes at 3 and 12 months and although only carvedilol improved left ventricular end-diastolic volumes compared to baseline, intergroup analysis showed no statistically significant differences in left ventricular volumes across the treatment period. Diastolic function, assessed by ventricular relaxation and filling patterns, was significantly improved at 12 months with both nebivolol and carvedilol therapy; however, only carvedilol demonstrated a benefit as early as 3 months.

Exercise duration, measured in seconds, significantly improved at 12 months with both nebivolol (894 ± 381 at baseline vs 994 ± 396 at 12 months; p = 0.01, 95% CI −181 to −18) and carvedilol (982 ± 475 at baseline vs 1124 ± 427 at 12 months; p = 0.01, 95% CI −248 to −36), with no statistically significant differences observed between the two groups. Of note, there was an initial decline in exercise capacity detected at 3 months with nebivolol (894 ± 381 at baseline vs 795 ± 392 at 3 months; p = 0.07, 95% CI −12 to −209). Although this was not statistically significant, this effect was not seen in the carvedilol group (982 ± 475 at baseline vs 1025 ± 419 at 3 months; p = 0.26, 95% CI −120 to −33) and compared with nebivolol, exercise capacity at 3 months was significantly better with carvedilol therapy (p = 0.002, 95% CI 0.03–0.48). One explanation for the initial decline in exercise capacity with nebivolol could be too rapid titration of the drug to target doses, which was accomplished over 4 weeks, a much faster titration than used in the SENIORS trial. Although, this study appears more favorable for carvedilol, a subsequent trial published by Lombardo and colleagues found conflicting results (CitationLombardo et al 2006). A similar patient population, 70 patients with NYHA class II or III heart failure and LVEF less than or equal to 40%, were randomized to carvedilol and nebivolol at similar doses used in the aforementioned trial. Patients were evaluated at baseline, 3, and 6 months, but data for baseline and 6 months only were reported. In contrast to the study by Patrianakos and colleagues, increases in LVEF and decreases in left-ventricular end-systolic volumes observed at 6 months were not statistically different from baseline; nor was there a difference observed between groups. Both carvedilol and nebivolol showed a trend towards an increased exercise capacity at 6 months and there was no reported decline in exercise capacity with nebivolol at earlier assessments. Both of these trials enrolled a small number of patients and evaluated surrogate endpoints. The study by Patrianakos and colleagues was performed in patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy so extrapolation to the general heart failure population is inappropriate given that ischemic heart disease is one of the most common causes of chronic heart failure. Additionally, target doses of nebivolol 5 mg used in these comparator trials is lower than the 10 mg target dose used in the ENECA study and SENIORS trial discussed above. Any differences between nebivolol and carvedilol on clinical endpoints of mortality and hospitalizations for heart failure cannot be inferred from these trials. Larger trials with head-to-head comparisons of nebivolol, carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol are needed to further establish if one agent is any more beneficial than the others in increasing survival and decreasing hospitalizations for acute decompensated heart failure.

Tolerability

Clinical trial data suggest that nebivolol is generally well tolerated. Placebo-controlled trials have reported increased incidences of drug-related adverse events such as hypotension, bradycardia, and dizziness but this should be anticipated based on the mechanism of drug action (CitationUhlir et al 1997; CitationBrehm et al 2002; CitationEdes et al 2005; CitationFlather et al 2005). When compared with other agents in its class, however, these adverse events have not been shown to occur any more frequently with nebivolol, and in fact there is some evidence to suggest that bradycardia occurs less frequently with nebivolol than with alternate beta-adrenergic blockers in the first few weeks of treatment (CitationVan Neuten et al 1998; CitationCzuriga et al 2003; CitationGrassi et al 2003). The mechanism for this has not been well described and, due to the short-term duration of the clinical studies, it is unclear if this response would be sustained with long-term therapy.

Nebivolol does not appear to impair insulin sensitivity, glucose levels or lipoprotein levels and seems to have a more favorable effect on these metabolic parameters than other beta-adrenergic blockers (CitationFogari et al 1997; CitationPesant et al 1999; CitationPoirier et al 2001; CitationRizos et al 2003; CitationCelik et al 2006; CitationPeter et al 2006). Laboratory assessments of kidney function, liver function and hematology tests before and during therapy with nebivolol indicate no adverse effects on each of these systems (CitationEdes et al 2005).

Conclusion

Nebivolol is currently marketed in Europe for the treatment of hypertension and heart failure and is under FDA review for use in the US. Evidence shows that nebivolol, titrated to a maximum dose of 10 mg, is a potentially promising therapeutic option for the treatment of chronic heart failure when added to standard therapy. Its unique mechanism of selectively blocking beta1-receptors and decreasing peripheral vascular resistance by enhancing nitric oxide bioavailability distinguish it from other agents in its class; however the clinical significance of this still needs to be defined. Since not all beta-adrenergic blockers have proved to be effective for the treatment of heart failure, the addition of nebivolol to the current armamentarium of carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol is encouraging and provides more options for individualizing patient therapy. Specifically, and in light of recent evidence for other agents known to work via the nitric oxide pathway, nebivolol may prove to be more useful than other beta-adrenergic blockers in African American patients and those suspected of having decreased nitric oxide bioavailability as an underlying pathophysiology of disease (CitationTaylor et al 2004). Large-scale clinical trials are needed, however, to test this hypothesis. Additionally, without head-to-head trials assessing mortality or hospitalizations for decompensated heart failure with nebivolol, it is premature to comment on which beta-adrenergic blocker is preferred for heart failure management. Nebivolol is the only agent to date that has evidence supporting use of beta-adrenergic blockers in the treatment of elderly patients with chronic heart failure. At this time, numerous clinical studies with nebivolol are in progress and include: an assessment of the role of nebivolol in the treatment of diastolic heart failure; use of nebivolol in African American patients with hypertension; and a comparison of nebivolol and metoprolol in patients with subclinical left ventricular dysfunction (CitationThe Menarini Group 2007).

References

- A. Menarini Pharmaceuticals UK LtdNebilet 5 mg tablets: prescribing information (UK) [Online]2005 Accessed 26 November 2006. URL: http://emc.medicines.org.uk

- AstraZenecaLPToprol-XL (metoprolol succinate): prescribing information (USA) [online]2006 Accessed 25 March 2007. URL: http://www.astrazeneca-us.com/pi/toprol-xl.pdf

- BristowMRNelsonPMinobeWCharacterization of ±1-adrenergic receptor selectivity of nebivolol and various other beta-blockers in human myocardium [abstract]J Hypertens200518A512

- BrixiusKBundkirchenABolckBNebivolol, bucindolol, metoprolol and carvedilol are devoid of intrinsic sympathomimetic activity in human myocardiumBr J Pharmacol20011331330811498519

- BowmanAJChenCPFordGANitric oxide mediated venodilator effects of nebivololBr J Clin Pharmacol1994381992047826820

- BrehmBRWolfSCGornerSEffect of nebivolol on left ventricular function in patients with chronic heart failure: a pilot studyEur J Heart Fail200247576312453547

- CelikTLyisoyAKursakliogluHComparative effects of nebivolol and metoprolol on oxidative stress, insulin resistance, plasma adiponectin and soluble P-selectin levels in hypertensive patientsJ Hypertens200624591616467663

- CheymolGWoestenborghRSnoeckEPharmacokinetic study and cardiovascular monitoring of nebivolol in normal and obese subjectsEur J Clin Pharmacol19975149389112066

- CIBIS-II Investigators and CommitteesThe Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II)Lancet199935391310023943

- CockcroftJRChowienczykPJBrettSENebivolol vasodilates human forearm vasculature: evidence for an L-arginine/NO-dependent mechanismJ Pharmacol Exp Ther19953741067717562470

- CominaciniLPasiniAFGarbinUNebivolol and its 4-keto derivative increase nitric oxide in endothelial cells by reducing its oxidative inactivationJ Am Coll Cardiol20034218384414642697

- CzurigaIRiecanskyIBodnarJComparison of new cardioselective beta-blocker nebivolol with bisoprolol in hypertension: the nebivolol, bisoprolol multicenter study (NEBIS)Cardiovasc Drugs Ther2003172576314574084

- DessyCSaliezJGhisdalPEndothelial β3-adrenoreceptors mediate nitric oxide-dependent vasorelaxation of coronary microvessels in response to the third-generation β-blocker nebivololCirculation2005112119820516116070

- EdesIGasiorZWitaKEffects of nebivolol on left ventricular function in elderly patients with chronic heart failure: results of the ENECA studyEur J Heart Fail20057631915921805

- Eon Labs, Inc.Bisoprolol fumurate and hydrochlorothiazide tablets: prescribing information (USA)2004

- FlatherMDShibataMCCoatsAJSRandomized trial to determine the effect of nebivolol on mortality and cardiovascular hospital admission in elderly patients with heart failure (SENIORS)Eur Heart J2005262152515642700

- FogariRZoppiALazzariPComparative effects of nebivolol and atenolol on blood pressure and insulin sensitivity in hypertensive subjects with type II diabetesJ Hum Hypertens19971175379416986

- FrishmanWHAlwarshettyMβ-adrenergic blockers in systemic hypertension: pharmacokinetic considerations related to the current guidelinesClin Pharmacokinet2002415051612083978

- GauthierCLeblaisVLesterKThe negative inotropic effect of β3-adrenoreceptor stimulation is mediated by activation of a nitric oxide synthase pathway in human ventricleJ Clin Invest19981021377849769330

- GlaxoSmithKlineCoreg (carvedilol): prescribing information (USA) [online]2007 Accessed 25 March 2007. URL: http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/us_coreg.pdf

- GosgnachWBoixelCNevoNNebivolol induces calcium-dependent signaling in endothelial cells by a possible β-adrenergic pathwayJ Cardiovasc Pharmacol200138191911483868

- GrassiGTrevanoFGFacchiniAEfficacy and tolerability profile of nebivolol vs. atenolol in mild-moderate essential hypertension: a double-blind randomized multi-centre trialBlood Press Suppl20032354014761075

- HjalmarsonAGoldsteinSFagerbergBEffect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF)Lancet19993532001710376614

- HuntSAAbrahamWTChinMHACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure) [online]2005 American College of Cardiology Website. URL: http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/failure//index.pdf

- IgnarroLJExperimental evidences of nitric oxide-dependent vasodilatory activity of nebivolol, a third-generation β-blockerBlood Press Suppl2004121615587107

- JanssenPMLZeitzORahmanAProtective role of nebivolol in hydroxyl radical induced injuryJ Cardiovasc Pharmacol200138Suppl 3S172311811388

- JessupMBrozenaSHeart failureN Engl J Med200334820071812748317

- KalinowskiLDobruckiITMalinskiTRace-specific differences in endothelial function: predisposition of African Americans to vascular diseasesCirculation200410925111715159296

- KamaliFHowesAThomasSHLA pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interaction study between nebivolol and the H2-receptor antagonists cimetidine and ranitidineBr J Clin Pharmacol19974320149131955

- KinlaySCreagerMAFukumotoMEndothelium-derived nitric oxide regulates arterial elasticity in human arteries in vivoHypertension20013810495311711496

- KomajdaMLapuertaPHermanNAdherence to guidelines is a predictor of outcome in chronic heart failure, the MAHLER surveyEur Heart J2005261653915827061

- LawrenceTELiuSBlandTMSingle-dose pharmacokinetics and anticoagulant activity of warfarin is unaffected by nebivolol in healthy volunteers [abstract]Clin Pharmacol Ther2005a77P39

- LawrenceTELiuSFisherJNo interaction between nebivolol and digoxin in healthy volunteers [abstract]Clin Pharmacol Ther2005b77P76

- LawrenceTEChienCLiuSNo effect of concomitant administration of nebivolol and losartan in healthy volunteers genotyped for CYP2D6 status [abstract]Clin Pharmacol Ther2005c77P82

- LawrenceTELiuSDonnellyCMA phase I open-label multiple dose study assessing the pharmacokinetic interaction of hydrochlorothiazide and nebivolol HCl in healthy volunteersAAPS PharmSci [online journal]20035 Abstract T2332. Accessed 30 November 2006. URL: http://www.aapsj.org/abstracts/am_abstracts2002.asp

- LefebvreJPoirierLPoirierPThe influence of CYP2D6 phenotype on the clinical response of nebivolol in patients with essential hypertensionBr J Clin Pharmacol2006 published online 10 November 2006

- LekakisJPProtogerouAPapamichaelCEffect of nebivolol and atenolol on brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilation in patients with coronary artery diseaseCardiovasc Drugs Ther2005192778116187009

- LombardoRMRReinaCAbrignaniMGEffects of nebivolol versus carvedilol on left ventricular function in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left ventricular systolic functionAm J Cardiovasc Drugs200662596316913827

- McMurrayJCohen-SolalADietzRPractical recommendations for the use of ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists and angiotensin receptor blockers in heart failure: Putting guidelines into practiceEur J Heart Fail200577102116087129

- MasonRPNitric oxide mechanisms in the pathogenesis of global riskJ Clin Hypertens200688 Suppl 2318

- MasonRPKalinowskiLJacobRFNebivolol reduces nitroxidative stress and restores nitric oxide bioavailability in endothelium of Black AmericansCirculation2005112379580116330685

- MortonTTuHCLiuSA phase I open-label multiple-dose study of the pharmacokinetic interaction between nebivolol HCl and spironolactone in healthy volunteersAAPS PharmSci [online journal]20035 Abstract T2333. Accessed 30 November 2006. URL: http://www.aapsj.org/abstracts/am_abstracts2002.asp

- MoncadaSHiggsAThe L-arginine-nitric oxide pathwayN Engl J Med19933292002127504210

- MortonTLLiuSPhillipsJMPharmacokinetics of nebivolol and ramipril are not affected by coadministration [abstract]Clin Pharmacol Ther200577P77

- OpieLHCommerfordPJGershBJControversies in ventricular remodelingLancet20063673566716443044

- PackerMBristowMRCohnJNThe effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failureN Engl J Med19963341349558614419

- PackerMCoatsAJSFowlerMBEffect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failureN Engl J Med20013441651811386263

- PasiniAFGarbinUNavaMCNebivolol decreases oxidative stress in essential hypertensive patients and increases nitric oxide by reducing its oxidative inactivationJ Hypertens2005235899615716701

- PanzaJAQuyyumiAABrushJEAbnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertensionN Engl J Med19903232272355955

- PatrianakosAPParthenakisFIMavrakisHEComparative efficacy of nebivolol versus carvedilol on left ventricular function and exercise capacity in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. A 12-month studyAm Heart J2005150985e9e1816084141

- PesantYMarc-AureleJBielmannPMetabolic and antihypertensive effects of nebivolol and atenolol in normometabolic patients with mild-moderate hypertensionAm J Ther199961374710423656

- PeterPMartinUSharmaAEffect of treatment with nebivolol on parameters of oxidative stress in type 2 diabetics with mild to moderate hypertensionJ Clin Pharm Ther200631153916635049

- PoirierLClerouxJNadeauAEffects of nebivolol and atenolol on insulin sensitivity and haemodynamics in hypertensive patientsJ Hypertens20011914293511518851

- RizosEBairaktariEKostoulaAThe combination of nebivolol plus pravastatin is associated with a more beneficial metabolic profile compared with that of atenolol plus pravastatin in hypertensive patients with dyslipidemia: a pilot studyJ Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther200381273412808486

- ShawAABlandTMTuHCSingle-dose, relative bioavailability and food effect study of nebivolol hydrochloride in healthy volunteers characterized according to their metabolizing statusAAPS PharmSci [online journal]2003a5 Abstract W5238. Accessed 30 November 2006. URL: http://www.aapsj.org/abstracts/am_abstracts2002.asp

- ShawAABlandTMTuHCSingle-dose, dose-proportionality pharmacokinetic study of nebivolol hydrochloride in healthy volunteers characterized according to their metabolizing statusAAPS PharmSci [online journal]2003b5 Abstract M1327. Accessed 30 November 2006 URL: http://www.aapsj.org/abstracts/am_abstracts2002.asp

- ShawAALiuSZachwiejaLFEffect of chronic administration of fluoxetine on the pharmacokinetics of nebivolol [abstract]Clin Pharmacol Ther200577P38

- SuleSSFrishmanWNebivolol: new therapy updateCardiol Rev2006142596416924166

- TaylorALZiescheSYancyCombination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failureN Engl J Med200435120495715533851

- TregaskisBFMcDevittDGβ-adrenoceptor-blocking drugs in the elderlyJ Cardiovasc Pharmacol199016Suppl 5S25S2811527132

- UhlirODvorakIGregorPNebivolol in the treatment of cardiac failure: a double-blind controlled clinical trialJ Card Fail1997327169547441

- The Menarini GroupClinical Trial Registry [online]2007 Accessed 2 April 2007 URL: http://www.menarini.com/english/clinical_trials/clinical_studies.htm

- SwedbergKClelandJDargieHGuidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: full text (update 2005): the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of CHF of the European Society of Cardiology [online]2005 Accessed 12 November 2006 URL: http://www.escardio.org/knowledge/guidelines/Chronic_Heart_Failure.htm

- TaylorALZiescheSYancyCCombination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failureN Engl J Med200435120495715533851

- Van BortelLMDe HoonJNKoolMJPharmacological properties of nebivolol in manEur J Clin Pharmacol199751379849049578

- Van NeutenLDe CreeJNebivolol: comparison of the effects of dl-nebivolol, d-nebivolol, l-nebivolol, atenolol, and placebo on exercise-induced increases in heart rate and systolic blood pressureCardiovasc Drugs Ther199812339449825177

- Van NeutenLTaylorFRRobertsonJISNebivolol vs. atenolol and placebo in essential hypertension: a double-blind randomized trialJ Hum Hypertens1213540

- Van PeerASnoeckEWoestenborghsRClinical pharmacology of nebivolol. A reviewDrug Invest19913Suppl 12530

- VeverkaANuzumDSJollyJLNebivolol: a third-generation β-adrenergic blockerAnn Pharmacother20064013536016822893