Abstract

The use of enoxaparin in conjunction with thrombolysis in ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI), has been recently investigated in several clinical trials. In 8 published open-label studies including about 10,000 patients, in which enoxaparin was compared to either placebo or unfractionated heparin (UFH), a general superiority of enoxaparin on both reinfarction/recurrent angina and patency of the infarct-related artery, was observed. Overall, bleeding rate with enoxaparin was higher than with placebo and comparable to UFH, with the exception of one study where pre-hospital administration induced a doubled incidence of intracranial bleeding in patients older than 75 years. In a recent double-blind, randomized, mega-trial including over 20,000 patients, the superior efficacy on in-hospital and 30-day adverse cardiac events (namely reinfarction), and comparable safety on intracranial bleedings of enoxaparin compared to UFH, was definitively proven.

In conclusion, initial intravenous bolus of enoxaparin followed by twice daily subcutaneous administration for about 1 week should be considered instead of intravenous UFH for the treatment of patients with STEMI receiving thrombolysis. Along with its easiness of use, not requiring laboratory monitoring, the subcutaneous administration of enoxaparin allows extended antithrombotic treatment, while permitting early mobilization (and rehabilitation) of patients.

Introduction

In patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing thrombolytic treatment with fibrin-specific agents (such as alteplase, reteplase, and tenecteplase), concurrent anticoagulation is warranted, in order to improve early recanalization and reduce reocclusion and reinfarction rates (CitationVan de Werf et al 2003; CitationAntman et al 2004). The need for systemic anticoagulation is less compelling when non-specific agents (such as streptokinase, anistreplase or urokinase) are used, since they produce a profound and prolonged systemic coagulopathy, which make these agents acting as anticoagulants themselves (CitationVan de Werf et al 2003; CitationAntman et al 2004). In the setting of STEMI treated with thrombolysis, conjunctive systemic anticoagulation has been traditionally carried out by means of a 24–48 hours intravenous course of unfractionated heparin (UFH) (CitationVan de Werf et al 2003; CitationAntman et al 2004). However, the efficacy of such treatment is known to be suboptimal, probably due to the several pharmacokinetic (ie, binding to plasma proteins with consequent variable anticoagulant response) and biophysical (ie, inability to inactivate factor Xa in the prothrombinase complex and thrombin bound to fibrin) limitations of UFH (CitationHirsh et al 2001).

The low-molecular-weight heparin enoxaparin is potentially more effective than UFH because of its pharmacological peculiarities. The anticoagulant effect of enoxaparin in fact, is exerted mainly by inactivating factor Xa, therefore inducing a more proximal inhibition of the coagulation cascade which in turn, results in a ratio of anti-factor Xa to anti-factor IIa activity of 3.8:1 (CitationAntman 2001). In addition, the absence of a significant binding to plasma proteins and platelet factors increases the bioavailability and plasma half-life of enoxaparin, therefore rendering the dose-response relationship more predictable (as opposed to UFH which shows wide fluctuations of its anticoagulant effect), with consequent no need for therapeutic monitoring (CitationAntman 2001; CitationHirsh et al 2001).

Enoxaparin has been extensively investigated in non ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes, where it was proven at least as effective as intravenous UFH (CitationCohen et al 1997; CitationAntman et al 1999). Whereas either intravenous UFH administration or subcutaneous enoxaparin administration is the anticoagulation treatment currently recommended for the management of patients with non ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (CitationBertrand et al 2002; CitationBraunwald et al 2002), the current standard of treatment after thrombolysis in STEMI is represented by intravenous UFH, being subcutaneous enoxaparin only regarded as an acceptable alternative (CitationAntman et al 2004).

Until very recently in fact, the evidence on the efficacy and safety of enoxaparin in this setting was derived from few open-label studies, generally including relatively small populations (CitationGlick et al 1996; CitationASSENT 2001; CitationRoss et al 2001; CitationAntman et al 2002; CitationBaird et al 2002; CitationSimoons et al 2002; CitationWallentin et al 2003; CitationTatu-Chitoiu et al 2004). In 2006, the results of a double-blind, randomized, mega-trial comparing the effect of enoxaparin with that of UFH in over 20,000 patients undergoing thrombolysis for STEMI were published, therefore clarifying the role of enoxaparin in this clinical setting (CitationAntman et al 2006).

Overview and analysis of the open-label clinical studies

In 8 open-label published studies, enoxaparin was evaluated in about 10,000 patients (). In these studies, the efficacy and safety of enoxaparin, in conjunction with either fibrin-specific (CitationASSENT 2001; CitationRoss et al 2001; CitationAntman et al 2002; CitationWallentin et al 2003; CitationTatu-Chitoiu et al 2004), non fibrin-specific (CitationGlick et al 1996; CitationSimoons et al 2002) or either one (CitationBaird et al 2002) of the thrombolytic agents, was compared with either placebo (CitationGlick et al 1996; CitationSimoons et al 2002) or UFH (CitationASSENT 2001; CitationRoss et al 2001; CitationAntman et al 2002; CitationBaird et al 2002; CitationWallentin et al 2003; CitationTatu-Chitoiu et al 2004) ().

Table 1 Design of the Studies

Enoxaparin versus placebo ( and )

CitationGlick et al (1996) randomized 103 patients to either subcutaneous enoxaparin 4,000 IU/day or placebo for the next 25 days, following treatment with aspirin, streptokinase and UFH for 5 days. The primary end-point of combined occurrence of unstable angina, reinfarction and death at 6 months was significantly reduced in the enoxaparin group (14% vs 43%; p = 0.01), mainly as a consequence of the decreased reinfarction rate (5% vs 22%; p = 0.02), since the occurrence of unstable angina (9% vs 22%) and death (0% vs 2%) were comparable.

Table 2 Results of the studies

In the AMI-SK study (CitationSimoons et al 2002), 496 patients treated with aspirin and streptokinase were randomized to enoxaparin (30 mg intravenous bolus followed by 1 mg/kg twice daily subcutaneously for 3–8 days) or placebo. The primary end-point was the infarct-related artery (IRA) patency rate at 5–10 days, while secondary end-points were ST-segment resolution at 90’ and 180’ and occurrence of combined death, reinfarction, recurrent angina and major bleedings at 30 days. Enoxaparin was significantly more effective on the primary end-point (TIMI 3 flow grade 70% vs 58%; p = 0.01 and TIMI 2–3 flow grade 88% vs 72%; p = 0.001) and complete ST-segment resolution both at 90’ (16% vs 11%; p = 0.01) and 180’ (36% vs 25%; p = 0.004). Clinical events at 30 days were also significantly reduced in the enoxaparin group (13% vs 21%; p = 0.03), mainly as a consequence of the reduction of reinfarction (2% vs 7%; p = 0.01), whereas major haemorrhages were more frequent, although this difference was not statistically significant (5% vs 3%).

Enoxaparin versus UFH ( and )

In the HART-II study (CitationRoss et al 2001), 400 patients receiving aspirin and accelerated rt-PA, were randomized to intravenous bolus of enoxaparin 30 mg followed by 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily or intravenous bolus of UFH 5.000 IU followed by 15 IU/kg/h for at least 3 days. The primary end-point was the IRA patency at 90’ and 5–7 days, while the secondary end-point was the occurrence of major bleedings. At 90’ TIMI 2–3 (80% vs 75%) and TIMI 3 (53% vs 48%) flow grades in the IRA did not significantly differ in the two groups. Also, the reocclusion rate at 5–7 days was comparable, although a clear trend favoring enoxaparin was evident (3% vs 9%). Major bleedings occurred with similar frequency in both groups (5.6% vs 5%).

In the ASSENT-3 trial (CitationASSENT 2001), 6095 patients treated with aspirin were randomized to: 1) full-dose tenecteplase and enoxaparin (30 mg intravenous bolus followed by 1 mg/kg to be repeated every 12 h up to hospital discharge or revascularization, for a maximum of 7 days); 2) half-dose tenecteplase with weight-adjusted low-dose UFH (40 IU/kg bolus followed by 7 IU/kg) and a 12-h infusion of abciximab; 3) full-dose tenecteplase and weight-adjusted UFH (60 IU/kg bolus followed by 12 IU/kg/h) for 48 h. Primary end-points were the composites of 30-day mortality, in-hospital reinfarction/refractory ischemia (efficacy end-point), and the above end-points plus in-hospital intracranial hemorrhage/major bleedings (efficacy plus safety end-point). In association with full-dose tenecteplase, enoxaparin was significantly more effective on the primary efficacy end-point (11% vs 15%; p = 0.0001), as well as on the primary efficacy plus safety end-point (14% vs 17%; p = 0.004). The association of abciximab and UFH influenced both efficacy and efficacy plus safety end-points comparably to enoxaparin and superiorly to UFH. Enoxaparin significantly reduced in-hospital reinfarction (3% vs 4%; p = 0.02) and refractory ischemia (5% vs 7%; p < 0.0001), along with in-hospital death/reinfarction (7% vs 9%; p = 0.02). Major hemorrhagic complications were not significantly different with enoxaparin as compared to UFH (3% vs 2%).

The ENTIRE-TIMI 23 study (CitationAntman et al 2002) was carried out on 483 patients to determine the effect on the 60’ patency rate of the IRA of 4 pharmacologic regimens, including the three evaluated in the ASSENT-3 trial (CitationASSENT 2001), plus an additional one with half-dose tenecteplase associated with enoxaparin 1 mg/kg every 12 h subcutaneously (to be continued up to 8 days) and 12-h intravenous abciximab infusion. The 4 regimens were similarly effective on the primary end-point of IRA TIMI 3 flow grade at 60’, which was about 50% in all groups. When pooling the results of the different groups according to heparin treatment, the TIMI 3 (50% vs 51%) and TIMI 2–3 (75% vs 78%) flow grade rates were comparable. A favorable trend towards a complete ST-segment resolution at 180’ was observed in enoxaparin groups (pooled rate: 50% vs 43%). Evaluation at 30 days by a blinded Clinical Events Committee of the clinical efficacy end-points showed significantly less death/reinfarction (4% vs 16%; p = 0.005) with enoxaparin, when administered with full-dose tenecteplase. This was mainly due to the reduction in reinfarction (2% vs 12%; p = 0.003), which could also be observed when pooling all enoxaparin vs all UFH patients (5% vs 11%; p = 0.01). No effect of the two heparin regimens was apparent with the combination treatments including abciximab. Through 30 days, the occurrence of major bleedings was similar (about 2%) in both groups treated with full-dose tenecteplase, regardless of the heparin regimen used. When abiciximab was added, a trend towards a higher bleeding rate was observed with enoxaparin as compared to UFH (9% vs 5%). Such a trend was also apparent for enoxaparin when pooling patients with respect to the heparin regimen adopted (5% vs 4%).

CitationBaird et al (2002) enrolled 300 patients receiving streptokinase or anistreplase (but not aspirin, which was given only at the end of the investigated treatment), who were randomized to a 4-day regimen with either enoxaparin 4.000 IU intravenous bolus followed by 4.000 IU three times daily subcutaneously or UFH intravenous 5.000 IU bolus followed by 30.000 IU/day infusion. The primary end-point was the occurrence at 90 days of the composite of death, reinfarction or rehospitalization due to unstable angina. Enoxaparin was significantly more effective than UFH (26% vs 36%; p = 0.04), leading to a 30% relative risk reduction of death, reinfarction or recurrent angina. This effect was obtained through a consensual reduction of any single component of the composite end-point. Significant bleeding occurred comparably in the two treatment groups (3% vs 4%).

In the ASSENT-3 PLUS study (CitationWallentin et al 2003), 1,639 patients were randomly assigned in a pre-hospital setting to treatment with tenecteplase and either enoxaparin (30 mg intravenous bolus followed by 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily for a maximum of 7 days) or weight-adjusted UFH (60 IU/kg intravenous bolus followed by 12 IU/kg infusion) for 48 hours. The primary end points were: composite of 30-day mortality or in-hospital reinfarction/refractory ischemia (efficacy end point) and composite of the previous plus in-hospital intra-cranial hemorrhage/major bleedings (efficacy plus safety end point). Enoxaparin was comparable to UFH on both the primary efficacy (14% vs 17%) and efficacy plus safety (18% vs 20%) end points. Analysis of the individual components of the end points showed a reduction in in-hospital reinfarction (4% vs 6%; p = 0.03) and refractory ischemia (4% vs 7%; p = 0.07) rates, but an increase in total stroke (3% vs 2%; p = 0.03) and intracranial hemorrhage (2% vs 1%; p = 0.05) with enoxaparin. The increase in intracranial hemorrhage however, was seen exclusively in patients over 75 years of age.

The ASENOX study (CitationTatu-Chitoiu et al 2004) included 633 consecutive patients who received aspirin and were randomly assigned to either: (1) streptokinase 1.500.000 U in an accelerated fashion (ie, over 20’, either as a full dose or double infusion of 750.000 U in 10’ separated by 50’), plus an intravenous bolus of enoxaparin 40 mg followed by 1 mg/kg subcutaneously every 12 h for 5–7 days (ASKEnox group = 165 patients); (2) the same accelerated streptokinase regimen plus UFH 1,000 IU/h for 48–72 h (ASKUFH group = 264 patients); or (3) streptokinase 1.500.000 U over 60’ plus UFH 1,000 IU/h for 48–72 h (SSKUFH group = 204 patients). When considering the 429 patients in the ASKEnox and ASKUFH groups, the coronary reperfusion rate (defined as cessation of chest pain during the first 180’ of thrombolysis, rapid reduction of ST-segment elevation by more than 50% of the initial value within the first 180’ and rapid increase in plasma CK and CK-MB with a peak in the first 12 h) was comparable (78% vs 74%). Also 30-day mortality was comparable in both groups (6% vs 7%) and neither significant difference in the incidence of major or minor hemorrhage was observed.

A pooled analysis of the studies where major adverse cardiac events, such as reinfarction and death, were evaluated in comparison to UFH, shows a consensual favorable effect of enoxaparin at both 7 and 30 days, with the only exception of ASSENT-3 PLUS (CitationWallentin et al 2003) where a trend towards an increased mortality was observed ( and ). Overall, the short- and medium-term beneficial effect of enoxaparin was statistically significant for the in-hospital/7 days reinfarction rate (RR reduction 39%), as well as for the 30-day combined occurrence of death and reinfarction (RR reduction 30%) ( and ). As regards mortality, enoxaparin treatment was associated with a favorable, albeit non significant, effect both during hospitalization/at 7 days (RR reduction 11%) and at 30 days (RR reduction 2%) ( and ). A similar analysis of the pooled data relative to the incidence of major bleedings in the studies comparing enoxaparin and UFH, showed a favorable, although not statistically significant, effect of enoxaparin during hospitalization/at 7 days (RR reduction 14%), whereas a trend towards an increase in major hemorrhagic complications is apparent at 30 days (RR increase 76%) (). However, the limited number of patients evaluated and the someway discordant occurrence of major bleeding in the individual studies, a trend towards an increase being observed in the ASSENT-3 trial (CitationASSENT 2001), as opposed to the ENTIRE-TIMI 23 trial (CitationAntman et al 2002) were major bleedings tended to be less, should be acknowledged ( and ).

Table 3 Pooled analysis of the results and relative risk (RR) of in-hospital/7-day reinfarction and death in the open-label studies

Table 4 Pooled analysis of the results and Relative Risk (RR) of 30-day reinfarction and death in the open-label studies

Table 5 Pooled analysis of the results and relative risk (RR) of in-hospital/7 days and 30-day major bleedings in the open-label studies

Comment on the open-label studies

The differences in study designs, end-points evaluated and treatment modality and duration () make difficult an analysis of the efficacy and safety of enoxaparin as an adjunct to thrombolysis in STEMI, both on angiographic and clinical end points ().

In general however, enoxaparin showed a somewhat higher efficacy than UFH on both early (60–90 minutes) and late (5–10 days) patency rates and reocclusion rate of IRA (CitationRoss et al 2001; CitationAntman et al 2002) (). Formal statistical significance however was never reached, probably due to the small size of the population. When compared to placebo, as in the AMI-SK study (CitationSimoons et al 2002), enoxaparin proved highly effective on the IRA patency rate (TIMI 3 flow grade at 8 days: 70% and 58%; p < 0.01) ().

Regarding the clinical end-points, both efficacy and safety of enoxaparin appear superior, not only to placebo, but also to UFH, although the above mentioned differences in study designs and results must be kept in mind (-). When noting that the most important clinical end point (ie, mortality) was not significantly influenced by enoxaparin, it should be taken into account that none of the studies was neither designed nor sized to detect such a difference. On the other hand, the incidence of the other two individual efficacy end-points (ie, reinfarction and recurrent ischemia/angina) was favorably influenced by enoxaparin. As compared to placebo, treatment with enoxaparin was associated with a reduced occurrence of combined angina and reinfarction (CitationGlick et al 1996; CitationSimoons et al 2002). In comparison with UFH, the effect of enoxaparin on reinfarction/recurrent ischemia was a little less concordant, although a trend towards a lower occurrence was consistently observed (CitationASSENT 2001; CitationAntman et al 2002; CitationBaird et al 2002; CitationWallentin et al 2003). Several reasons should be taken into account when trying to explain such a finding. First, the definitions of these two events were highly variable in the various studies, ranging from recurrence of chest pain associated or not with ECG changes to chest pain with ECG changes determining re-hospitalization or performance of coronary angiography for recurrent angina/ischemia, and from recurrence of chest pain associated with ECG changes and (not quantified) increase in CK and AST to recurrence of chest pain at rest associated with ST-segment elevation and further increase (sometimes not specified, some other time defined as twice the upper normal limit or three times or five times the upper normal limit in case it was detected following coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting, respectively) in either total CK or CK-MB isoenzyme or troponins for reinfarction. In addition, in the ASSENT-3 study (CitationASSENT 2001), there was no central adjudication for the end-points of reinfarction and refractory ischemia, which were therefore confirmed by the individual investigators (although in accordance with pre-specified definitions). Second, the different treatment regimens with thrombolytic agents and heparins () may also have played an important role on the discordant effects observed on recurrent ischemia/angina and reinfarction rates. For example, the superior efficacy of enoxaparin compared to UFH on in-hospital refractory ischemia/reinfarction observed in both ASSENT-3 (CitationASSENT 2001) and ASSENT-3 Plus (CitationWallentin et al 2003) studies, and on the reinfarction rate at 30 days in the ENTIRE-TIMI 23 study (CitationAntman et al 2002), may well be ascribed to the longer duration of enoxaparin treatment, rather than to a real difference in the efficacy of the two drugs. Indeed, in the study by Baird et al. (CitationBaird et al 2002), where the duration of enoxaparin and UFH was identical, no significant difference on reinfarction and recurrent angina rates was observed.

The safety profile of enoxaparin, in association with aspirin and thrombolysis in STEMI, is characterized in general by an increased occurrence of both minor and major bleedings compared to placebo (CitationSimoons et al 2002) and substantially unchanged compared to UFH (CitationRoss et al 2001; CitationASSENT 2001; CitationAntman et al 2002; CitationWallentin et al 2003). Regarding major hemorrhages, which however, were variably defined in the various studies (fatal, intracranial, intraperitoneal, intraocular, requiring transfusion or surgical operation), no significant difference in the occurrence of intracranial bleeding was observed with enoxaparin as compared not only to UFH (CitationRoss et al 2001; CitationASSENT 2001; CitationAntman et al 2002; CitationBaird et al 2002), but also to placebo (CitationSimoons et al 2002), with the only exception of the ASSENT-3 Plus study (CitationWallentin et al 2003). In this study the administration of thrombolysis and enoxaparin in a pre-hospital setting was indeed associated with a twice higher occurrence of intracranial hemorrhage compared to UFH, although only in patients aged more than 75 years (2% vs 1%; p = 0.05) ().

The ExTRACT-TIMI 25 Study

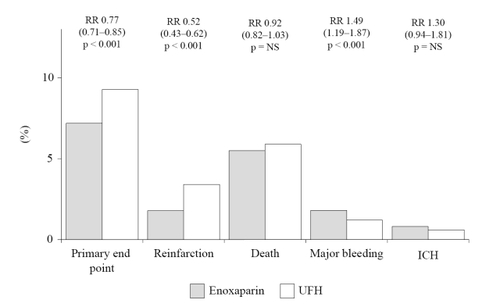

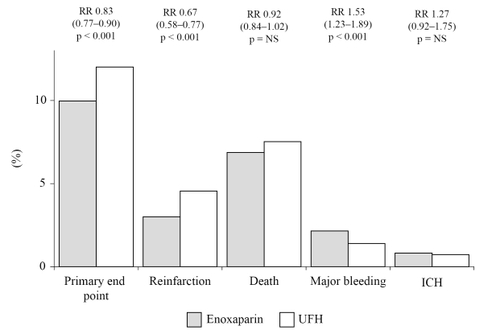

In this multi-center, double-blind, randomized trial, over 20,000 patients receiving either a fibrin- or non fibrin-specific thrombolytic and aspirin, were randomized to enoxaparin 30 mg as an intravenous bolus followed by 1 mg/kg twice daily subcutaneously for up to 8 days, or intravenous bolus of UFH 60 IU/kg followed by infusion of 12 IU/kg/h for 48 hours (CitationAntman et al 2006). The primary end-point was the composite of death or reinfarction at 30 days, whereas secondary end points were the composite of death and reinfarction/recurrent ischemia and the composite of death, recurrent reinfarction and disabling stroke at 30 days. Enoxaparin was significantly more effective than UFH on both in-hospital (7% vs 9%; p < 0.001) and 30-day (10% vs 12%; p < 0.001) primary end points ( and ). In both cases, this result was mainly driven by the significant decrease in reinfarction, since mortality was not substantially affected ( and ). Major bleedings were significantly more frequent with enoxaparin at both 8 and 30 days, although the occurrence of intracranial hemorrhage was comparable ( and ). However, the net clinical benefit at 30 days, defined as the combined occurrence of death, reinfarction and either nonfatal disabling stroke, major bleeding or intracranial hemorrhage, was significantly higher with enoxaparin, which was associated with a significant 14 to 18% relative risk reduction of these events compared to UFH (CitationAntman et al 2006).

Figure 1 Efficacy and safety outcomes at 8 days in the ExTRACT-TIMI 25 study.

Figure 2 Efficacy and safety outcomes at 30 days in the ExTRACT-TIMI 25 study.

Because of its design and size, the ExTRACT-TIMI 25 study (CitationAntman et al 2006) should be considered conclusive about the superior efficacy of enoxaparin in comparison to UFH for the treatment of patients receiving thrombolysis for STEMI. Again however, it cannot be determined whether this result is to be ascribed to a true superior antithrombotic effect of enoxaparin or instead to the longer duration of treatment (7 days vs 48 hours). Prolonged treatment with enoxaparin, which can be conveniently given subcutaneously without need for laboratory monitoring, is likely to effectively contribute to a more sustained antithrombotic effect, and should therefore strongly considered in these patients.

The higher occurrence of major bleedings may also well be ascribed to the longer duration of treatment, rather than to a superior dangerousness of enoxaparin ( and ). Since however, the most dreadful and disabling hemorrhagic complication, represented by intracranial bleeding, did not significantly differ in the two groups, the safety profile of enoxaparin should be considered satisfactory ( and ). It is of note however that among patients having a major bleeding episode, the 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in those receiving enoxaparin rather than UFH (0.8% vs 0.4%; p < 0.001), being hemorrhage the primary cause of death in both groups (70% vs 77%, respectively) (CitationAntman et al 2006). Although a clear explanation for such a finding is not apparent, the only partial response to protamine, as well as a possible delay in the recognition of an hemorrhagic complication (due to the lack of tight monitoring which may allow prompt correction of the intensity of anticoagulation when intravenous UFH is used), may account for the apparent increased fatality rate of hemorrhagic events with enoxaparin administration.

Conclusions

The administration of enoxaparin, as a conjunct to thrombolysis for STEMI, is superior to both placebo and UFH, in terms of in-hospital and 30-day incidence of reinfarction/recurrent ischemia, and angiographic end-points, such as patency and reocclusion rates of the IRA. Provided that patients aged older than 75 years are excluded, especially when thrombolysis is performed in a pre-hospital setting, also the risk of hemorrhage associated with enoxaparin administration is probably favourable as well. In addition, the easiness of subcutaneous administration and the lack of need for aPTT monitoring greatly increase its convenience, allowing also prolongation of treatment, without hampering early mobilization and rehabilitation of patients, while permitting extended antithrombotic treatment.

While waiting the current practice guidelines for the management of patients with STEMI (CitationVan de Werf et al 2003; CitationAntman et al 2004) to be updated in accordance with these new acquisitions, the administration of enoxaparin as an intravenous 30 mg bolus followed by twice daily 1 mg/kg subcutaneous administration for about 1 week should be considered for patients receiving thrombolysis for STEMI. As appearing from a recent meta-analysis of all randomized trials comparing various low-molecular-weight heparins to both placebo and UFH in association to thrombolysis for STEMI (CitationEikelboom et al 2005), the beneficial effect observed with enoxaparin is likely a property of the class of low-molecular-weight heparins, which therefore may probably be indifferently used.

Note

Dr. Rubboli reports having received lecture fees from Sanofi-Aventis, and Dr. Di Pasquale reports having received lecture fees from and having served on paid advisory board for Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Capecchi discloses no potential conflict of interest.

References

- AntmanEMThe search for replacements for unfractionated heparinCirculation20011032310411342482

- AntmanEMMcCabeCHGurfinkelEPEnoxaparin prevents death and cardiac ischemic events in unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: results of the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 11B trialCirculation1999100159360110517729

- AntmanEMLouwerenburgHWBaarsHFEnoxaparin as adjunctive antithrombin therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Results of the ENTIRE-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 23 TrialCirculation20021051642911940541

- AntmanEMAnbeDTArmstrongPWACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary and recommendation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelinesCirculation200411058863615289388

- AntmanEMMorrowDAMcCabeCHEnoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin with thrombolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med200635414778816537665

- [ASSENT] Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic regimen (ASSENT)-3 investigatorsEfficacy and safety of tenecteplase in combination with enoxaparin, abciximab, or unfractioned heparin: the ASSENT-3 randomised trial in acute myocardial infarctionLancet20013586051311530146

- BairdSHMenownIBAMcBrideSJRandomized comparison of enoxaparin with unfractioned heparin following fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarctionEur Heart J2002236273211969277

- BertrandMESimoonsMLFoxKAAManagement of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevationEur Heart J20022318094012503543

- BraunwaldEAntmanEMBeasleyJWACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the management of patients with unstable angina)J Am Coll Cardiol20024013667412383588

- CohenMDemersCGurfinkelEPfor the Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q-wave Coronary Events study groupA comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin with unfractionated heparin for unstable coronary artery diseaseN Engl J Med1997337447529250846

- EikelboomJWQuinlanDJMehtaSRUnfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin as adjuncts to thrombolysis in aspirin-treated patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction. A meta-analysis of the randomized trialsCirculation200511238556716344381

- GlickAKornowskiRMichowichYReduction of reinfarction and angina with use of low-molecular-weight heparin therapy after streptokinase (and heparin) in acute myocardial infarctionAm J Cardiol199677114588651085

- HirshJAnandSSHalperinJLGuide to anticoagulant therapy: heparin. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart AssociationCirculation20011032994301811413093

- RossAMMolhoekPLunderganCRandomized comparison of enoxaparin, a low-molecular-weight heparin, with unfractioned heparin adjunctive to recombinant tissue plasminogen activator thrombolysis and aspirin. Second trial of Heparin and Aspirin Reperfusion Therapy (HART-II)Circulation20011046485211489769

- SimoonsMLKrzeminska-PakulaMAlonsoAImproved reperfusion and clinical outcome with enoxaparin as an adjunct to streptokinase thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. The AMI-SK StudyEur Heart J20022312829012175665

- Tatu-ChitoiuGTeodorescuCCapraruPAccelerated streptokinase and enoxaparin in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (the ASENOX study)Pol Heart J2004604416

- Van de WerfFArdissinoDBetriuAManagement of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevationEur Heart J200324286612559937

- WallentinLGoldsteinPArmstrongPWEfficacy and safety of tenecteplase in combination with the low-molecular-weight heparin enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin in the prehospital setting. The Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT)-3 PLUS randomized trial in acute myocardial infarctionCirculation20031081354212847070