Abstract

A 41-year old female patient was admitted with acute onset of dyspnea and chest pain. Previous history revealed asthma, chronic sinusitis and eosinophilic proctitis. Electrocardiogram showed anterior ST-segment elevations and inferior ST-segment depression. Immediate heart catheterization revealed a distally occluded left anterior descending coronary artery, the occlusion being reversible after nitroglycerine. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was consistent with perimyocarditis. Hypereosinophilia and IgE elevation were present and Churg-strauss syndrome was diagnosed.

Introduction

Churg and Strauss initially described the syndrome as a necrotising vasculitis of medium-to-small sized veins and arteries, associated with eosinophilic infiltration around the vessels and adjacent tissues (CitationChurg and Strauss 1951). Cardiac involvement is a leading cause of mortality and a common clinical manifestation (CitationConron and Beynon 2000). About 40% of patients face cardiac problems including symptoms of congestive heart failure, pericardial effusions, or arterial hypertension (CitationSolans et al 2001; CitationMcGavin et al 2002; CitationLau et al 2004). Other consequences include myocarditis and intracardiac thrombosis (CitationOmmen et al 2000). Although vasospastic angina and myocardial infarction are unusual clinical manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS), the case we report suggests that it should be suspected in CSS cases.

Case report

A 41-year old female was admitted to our emergency department with acute respiratory distress and severe chest pain. Her symptoms had developed progressively over the last two weeks along with difficulties in activities that required fast walking or climbing stairs. She also experienced general weakness and systemic symptoms such as malaise the weeks before.

Her past medical history revealed no previous hospitalizations and no cardiovascular risk factors. In 2001, asthma was diagnosed. Since 2003, the patient suffered from chronic sinusitis and otitis media. Due to diarrhea in 2003, a colonoscopy was performed and proctitis was diagnosed. The histological results of the colon biopsy revealed extravascular eosinophilic infiltrates. The diagnosis of CSS was not considered at that time since no differential white blood count (WBC) has been done.

Initial laboratory findings revealed Troponin T elevation (0.40 μg/l, reference value <0.01 μg/l) as well as increased white blood cells (19,100/μl) and platelets (399,000/μl). In the course of diagnostic investigation differential WBC was performed and revealed eosinophilia of 68.2%, corresponding with an absolute value of 9,600/μl. C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum-creatinine as well as the glomerular filtration rate were in the normal range, however IgE was elevated (367 IE/ml; reference value 1–100 IE/ml). ANA, anti-ds-DNA, ENA and ANCA were negative. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ST-segment elevations in leads II, III and aVF and pronounced T inversions in leads V5 and V6.

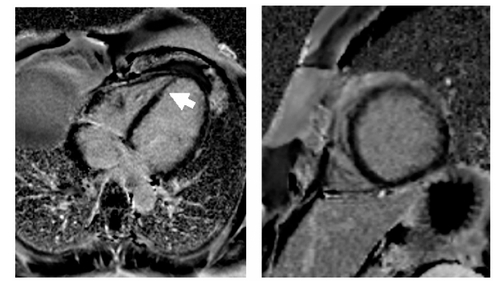

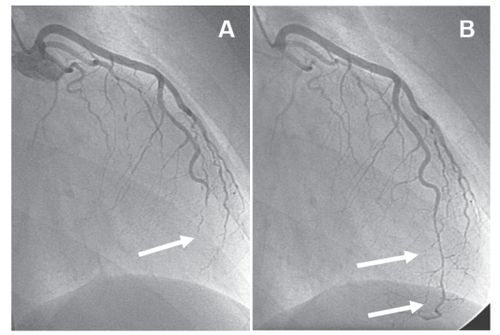

Coronary angiography revealed a distally occluded left anterior descending coronary artery (), the occlusion being reversible after nitroglycerine (). The maximum CK-level was 350 U/l (reference value <145 U/l) and CK-MB 44 U/l (reference value <24 U/l), respectively. A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the heart was performed to evaluate the extent of myocardial necrosis and the presence/absence of myocarditis.

Figure 1 Angiogram of the left coronary artery. The left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) is distally occluded (arrow in A); after intracoronary application of nitroglycerine the LAD is open (arrows in B), but demonstrating a long, severely diseased coronary segment that is significantly stenosed. Because of the long coronary segment involved, the small diameter and the suspicion of inflammatory origin of the stenosis, percutaneous coronary intervention was not attempted.

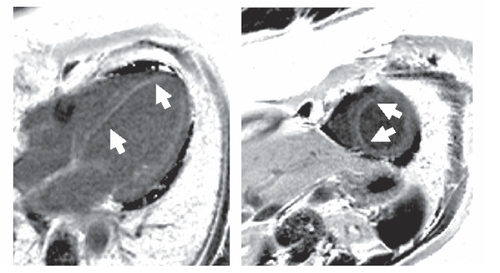

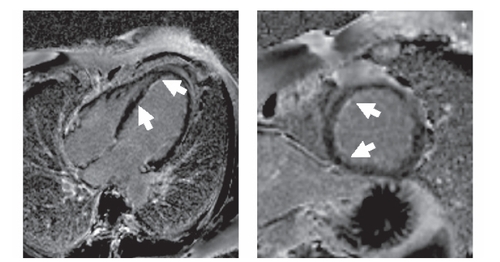

A contrast-enhanced phase sensitive inversion recovery sequence (PSIR) was used for the detection of late enhancement which is known to indicate scar formation/fibrosis or can be associated with acute myocarditis. A bandlike subendocardial hyperintensity was detected in the interventricular septum (). The distal occlusion of the LAD might have caused the subendocardial late enhancement finding in the apical septum. However, the late enhancement finding in the basal and medial part of the septum extended the territory that was supplied by the distal LAD and were most likely due to myocarditis. In addition, a small pericardial effusion was present. Follow up MRI demonstrated only mild regional wall hypokinesia of the apical septum, anterior and inferior wall.

Figure 2A Magnetic resonance imaging of the left ventricle. Phase sensitive T1-weighted contrast based late enhancement sequence (PSIR). A subendocardial bandlinke hyperintensity in the interventricular septum was found in the four chamber view and short axis orientation (arrow). A small pericardial effusion was present.

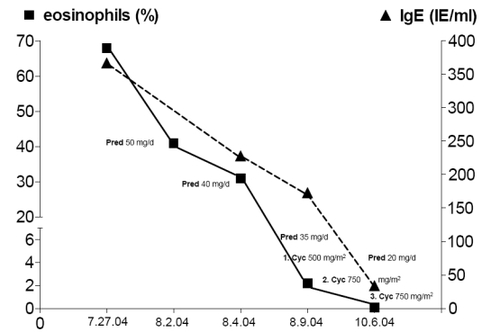

The presence of asthma, hypereosinophilia >10%, chronic sinusitis, and eosinophilic proctitis represent 4 of the 6 ACR criteria required for the classification of CSS. In addition, cardiac involvement was present due to coronary vasculitis and perimyocarditis which lead us to initiate the combination therapy of glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide. Oral corticosteroids were applied with an initial dosage of 50 mg prednisolone per day (1 mg/kg/d). In addition, monthly intravenous cyclophosphamide with 500 mg/m2 BSA increased to 750 mg/m2 BSA was initiated and continued over three months. Symptoms, eosinophilia, IgE count, Troponin T- and CK levels decreased to normal ranges (). Azathioprine with 2 × 50 mg per day was initiated to maintain remission. Oral corticosteroids were continuously tapered over a period of 20-weeks to a dosage of 5 mg per day and after additional 4-months, the patient had reached a stable remission. After 4 and 12-months, small areas of late enhancement persisted in the apical septum on MRI with regional hypokinesia in this region (, ).

Figure 2B Follow-up after four months. Subendocardial late enhancement persisted, though smaller in extension as seen in this PSIR late enhancement image of the four chamber view and short axis orientation. No pericardial effusion.

Discussion

We describe a patient who presented with an acute coronary syndrome, eosinophilia, and elevated IgE-levels. The diagnosis of CSS was made. CSS is a rare diffuse vasculitis that is almost invariably accompanied by severe asthma. Although overall prognosis is good, diffuse organ involvement, in particular cardiovascular and rare involvement of the central nervous system or renal system, suggests a poorer prognosis and can be fatal (CitationNoth et al 2003). CitationThe American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1990 criteria for the classification of CSS do not emphasize the cardiac symptoms (CitationMasi et al 1990). However, a review of the literature indicates that cardiac involvement is a poor prognostic factor, known to be a leading cause of mortality and a common clinical manifestation in CSS. Of note, patients with heart involvement are mainly ANCA-negative which is in agreement of this case (CitationSable-Fourtassou et al 2005; CitationSinico et al 2006). Cardiac inflammation may include eosinophilic endomyocarditis, coronary vasculitis, valvular heart disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, and pericarditis (CitationMorgan et al 1989; CitationRamakrishna and Midthun 2001;CitationPetrakopoulou et al 2005).

Fixed lesions, slowly regressing under therapy, have been more confidently related to CSS. However, coronary spasms have been seen in CSS patients, and this is frequently not clinically symptomatic, which might also be responsible for underdiagnosing CSS. Since the patients with cardiac involvement are at high risk, intravenous or oral cyclophosphamide in association with glucocorticoids are required (CitationNoth et al 2003). The switch to another less toxic immunosuppressant after remission is currently not evidence-based medicine.

Conclusion

Because of its multiorgan involvement, clinical diagnosis of CSS may be difficult to obtain. As reported here, the disease may present with clinical findings of an acute coronary syndrome. The association of perimyocarditis, hypereosinophilia, and elevated IgE-levels with a history of asthma were the key data to establish the diagnosis of CSS. Biopsy confirmation of vasculitis is complicated by the unpredictable and often sequential onset of disease manifestations of the various organs involved and by its incomplete evolution even in the affected organs. Mere MRI findings in patients free of cardiac symptoms should not be considered as basis for treatment decisions. However, MRI might be a helpful tool in the initial evaluation of CSS patients showing clinical or laboratory evidence of heart involvement. Consequently, this condition requires early and aggressive treatment with glucocorticoids in combination with cyclophosphamide.

However, onset of asthma associated with pulmonary infiltrates, renal disease, mononeuritis multiplex or, as presented by our patient, a combination of cardiac manifestation and proctitis should alert physicans to consider CSS as a potential differentential diagnosis in patients with these conditions and in particular with an acute coronary syndrome.

References

- ChurgJStraussLAllergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis, and periarteritis nodosaAm J Pathol19512727730114819261

- ConronMBeynonHLChurg-Strauss syndromeThorax200055870710992542

- LauEWCarruthersDMPrasadNChurg-Strauss syndrome as an unusual cause of spontaneous atraumatic intra-pericardial thrombosisEur J Echocardiogr2004565715113013

- MasiATHunderGGLieJTThe American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis)Arthritis Rheum19903310941002202307

- McGavinCRMarshallAJLewisCTChurg-Strauss syndrome with critical endomyocardial fibrosis: 10 year survival after combined surgical and medical managementHeart200287E511997435

- MorganJMRaposoLGibsonDGCardiac involvement in Churg-Strauss syndrome shown by echocardiographyBr Heart J19896246262605060

- NothIStrekMELeffARChurg-Strauss syndromeLancet20033615879412598156

- OmmenSRSewardJBTajikAJClinical and echocardiographic features of hypereosinophilic syndromesAm J Cardiol200086110310867107

- PetrakopoulouPFranzWMBoekstegersPVasospastic angina pectoris associated with Churg-Strauss syndromeNat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med200524849 quiz 49016265589

- RamakrishnaGMidthunDEChurg-Strauss syndromeAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20018660313 quiz 1311428732

- Sable-FourtassouRCohenPMahrAAntineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the Churg-Strauss syndromeAnn Intern Med2005143632816263885

- SinicoRADi TomaLMaggioreURenal involvement in Churg-Strauss syndromeAm J Kidney Dis200647770916632015

- SolansRBoschJAPerez-BocanegraCChurg-Strauss syndrome: outcome and long-term follow-up of 32 patientsRheumatology (Oxford)2001407637111477281