Abstract

Epidemiological studies of middle-aged populations generally find the relationship between alcohol intake and the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke to be either U- or J-shaped. This review describes the extent that these relationships are likely to be causal, and the extent that they may be due to specific methodological weaknesses in epidemiological studies. The consistency in the vascular benefit associated with moderate drinking (compared with non-drinking) observed across different studies, together with the existence of credible biological pathways, strongly suggests that at least some of this benefit is real. However, because of biases introduced by: choice of reference categories; reverse causality bias; variations in alcohol intake over time; and confounding, some of it is likely to be an artefact. For heavy drinking, different study biases have the potential to act in opposing directions, and as such, the true effects of heavy drinking on vascular risk are uncertain. However, because of the known harmful effects of heavy drinking on non-vascular mortality, the problem is an academic one. Studies of the effects of alcohol consumption on health outcomes should recognise the methodological biases they are likely to face, and design, analyse and interpret their studies accordingly. While regular moderate alcohol consumption during middle-age probably does reduce vascular risk, care should be taken when making general recommendations about safe levels of alcohol intake. In particular, it is likely that any promotion of alcohol for health reasons would do substantially more harm than good.

Keywords:

Introduction

Case-control and cohort studies of middle-aged populations have consistently demonstrated U- (or J-) shaped relationships between alcohol consumption and the incidence of major vascular diseases (in particular coronary heart disease [CHD]) (CitationBeaglehole and Jackson 1992; CitationCorrao et al 2000; CitationReynolds et al 2003). Typically, CHD risk among middle-aged people who drink light-to-moderate amounts of alcohol (usually defined as around 20 g to 30 g of alcohol per day) is found to be between 20% and 30% lower than for those who do not drink (CitationCorrao et al 2000). Similar findings, but perhaps weaker evidence of benefit, have been reported for stroke (CitationReynolds et al 2003). In contrast, the harmful effects of heavy drinking are equally well documented. People who drink excessively (usually defined as at least 40 g of alcohol per day) generally have higher rates of CHD and stroke than people who drink moderately, though often at a level only either comparable with, or slightly in excess of, the disease rates experienced by nondrinkers. While most of these studies have been of middle-aged men, several large studies have also demonstrated that these relations exist in middle-aged women (CitationFuchs et al 1995; CitationThun et al 1997).

So what could account for a U- or J-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of CHD and stroke? Is the association between light-to-moderate drinking and lower vascular risk causal, or a consequence of unknown biases in observational studies? Furthermore, if moderate alcohol intake (as opposed to abstinence) does reduce vascular risk, why is heavy drinking associated with increased vascular risk? In order to address these questions, it is important to appreciate several complicating issues (summarized in ). First, the amount of alcohol consumed is only one component of “alcohol exposure”. Both the type of drink consumed and the pattern of drinking may have important modifying influences on vascular risk independently of the amount. Thus, the apparent vascular benefit of light-to-moderate drinking (as well as the harm associated with heavy drinking) could be explained as much by differences in the way that alcohol is consumed in different drinking categories, as it is to differences in the amount of alcohol consumed. Second, alcohol consumption is an exposure that is difficult to measure accurately and therefore can be easily misclassified. Biases in the reporting of alcohol consumption may alter the magnitude and, if systematic, even the direction of apparent risk-relationships. This may be particularly relevant for case-control studies, in which cases are asked to recall what their drinking habits were prior to their heart attack or stroke. Perhaps more importantly, people who regularly drink light or moderate amounts of alcohol also tend to exhibit other characteristics that are particularly beneficial to health. For example, they may be more likely to take regular physical activity. It is possible that these other characteristics are reducing vascular risk, rather than alcohol. Alcohol consumption patterns also tend to change over time, either due to the presence of disease (so called “reverse-causality”) or sometimes as a natural consequence of aging. Single assessments of alcohol consumption recorded at the beginning of a cohort study may therefore be unable to accurately reflect true “average” exposures to alcohol during a study. In addition, if the non-drinking category contained a significant proportion of people who had given up alcohol because of ill health, their disease risks would not be truly reflective of the true risks associated with non-drinking. Finally, there may be bias in the literature, both in the tendency for authors and journals to publish “favorable” results (publication bias), and the common tendency for authors to interpret their results only in the context of their prior beliefs. Thus, for several reasons, there is some doubt when interpreting the alcohol—vascular disease risk relationship as entirely causal. Nonetheless, alcohol is known to have some favorable biological effects that would be expected to reduce vascular risk. In particular, it increases high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) (CitationRimm et al 1999), a protective risk factor for CHD (CitationSacks 2002), and possibly also for (non-hemorrhagic) stroke (CitationLindenstrom et al 1994; CitationTanne et al 1997; CitationWannamethee et al 2000). It also has a modest beneficial effect on thrombotic factors, particularly fibrinogen. On the other hand, it increases blood pressure, which might offset (to some degree at least) the expected benefits on blood lipids.

Table 1 Potential sources of bias in epidemiological studies of the relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of vascular disease

The purpose of this review is to consider to what degree these potential biases and potential causal mechanisms might credibly account for the shape and magnitude of the relationships between alcohol consumption and the risks of CHD and stroke. Each of the major potential sources of bias are reviewed and, where possible, the effects of taking them into account illustrated using examples from published studies. The most likely causal mechanisms and their expected effects are also reviewed using evidence from large overviews of epidemiological studies.

Alcohol and coronary heart disease

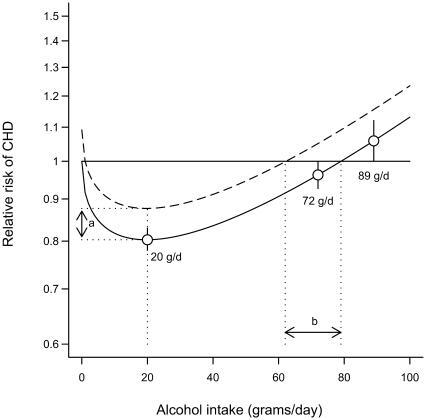

Since the early 1970s, many observational epidemiological studies have reported a cardioprotective effect of moderate amounts of alcohol. In a review of five case-control studies, seven prospective studies, two international comparisons, and one time-trend report published in 1984, it was concluded that moderate alcohol intake was associated with lower risks of CHD mortality, but that heavy drinking was associated with higher mortality compared with nondrinkers (CitationMarmot 1984). In 2000, a meta-analysis of 28 prospective studies which investigated the relationship between alcohol and CHD risk and which, based on factors relating to study design, data collection methods and data analysis strategy, were deemed to be of a “high quality”, estimated that 20 g of alcohol a day (1–2 standard drinks) was associated with a 20% (95% confidence index [CI] 17% to 22%) reduction in the relative risk of CHD (CitationCorrao et al 2000). This protective effect was found to persist up to a consumption as high as 72 g/day and only became significantly harmful after 89 g/day (approximately 7 standard drinks a day); see .

Figure 1 Impact of choice of reference category on the relationship between alcohol intake and the risk of coronary heart disease.

The solid line shows data from 28 cohort studies (adapted and reproduced with permission from Figure 2 of Corrao et al. 2004. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med, 38: 613-19) and shows the estimated risk-relationship when nondrinkers are used as the reference category. The dashed line shows the same curve with light drinkers (1 g/day) as the reference category. The distances a and b represent the extent that use of nondrinkers as the reference category might lead to overestimation of the benefits of moderate alcohol consumption and overestimation of the level at which alcohol consumption may become cardiotoxic.

Amount, type, or drinking pattern?

Total alcohol consumption, though the most widely used and probably the most informative, provides only one method of looking at an individual's overall “alcohol exposure”. For many years, it has been suggested that both the type of drink consumed (eg, beer, wine, or spirits) as well as the pattern of drinking (eg, daily with meals, weekends only) may have contributing effects on CHD risk that are separate from those of the total amount of alcohol consumed. Wine, for instance, has been widely claimed to contain substances other than ethanol that have cardioprotective effects. In fact, it has often been suggested that despite high smoking rates and typically high fat diets, the French experience low CHD rates because of their high levels of wine intake (CitationRenaud and de Lorgeril 1992). Numerous substances in wine related to platelet aggregation, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation inhibition, vasodilating effects and effects on the endothelium have been proposed as potentially beneficial (CitationFrankel et al 1993; CitationPace-Asciak et al 1995; CitationFlesch et al 1998; CitationIijima et al 2002), but none have so far been confirmed to be causally important. In populations where beer, wine, and spirits are all commonly consumed, several studies have indeed found wine drinkers to be at lower CHD risk than beer or spirit drinkers (CitationWannamethee and Shaper 1999; CitationGronbaek et al 2000; CitationTheobald et al 2000). However, when making these comparisons, it is important to take account of the very different socioeconomic characteristics these groups tend to have. In a meta-analysis of 26 observational studies, it was estimated that wine and beer reduced the risk of vascular disease by 32% and 22% respectively (CitationDi Castelnuovo et al 2002). However, because no meaningful relationship could be found between different amounts of beer intake and vascular risk, the results were difficult to interpret. In another meta-analysis of the effects of beer, wine, and spirits on CHD risk, the authors concluded that the major portion of the benefit associated with alcohol consumption was due to ethanol itself, rather than any other components of each type of drink (CitationRimm et al 1996). This view is indirectly supported by the observation that in the mainly beer-drinking populations of Bavaria (Germany) and the Czech Republic, the protective effects of alcohol are similar to those observed in the mainly wine drinking Mediterranean countries (CitationKeil et al 1997; CitationBobak et al 2000).

In addition to the type of alcohol consumed, the role that pattern of drinking may play in determining CHD risk has also generated much interest. In particular, drinking with meals (compared with drinking without meals) has been found to be associated with a beneficial effect on CHD risk and other outcomes (CitationTrevisan et al 2001, Citation2004), possibly due to effects on blood pressure (CitationFoppa et al 2002), thrombotic factors (CitationHendriks et al 1994) or lipids (CitationVeenstra et al 1990). In contrast, irregular heavy drinking (binge drinking) has been shown to be associated with increased CHD risk for many years. Indeed, it has been debated whether binge drinking may have been responsible for the sharp rise in national cardiovascular disease rates observed in Russia during the early 1990s (following a previously successful anti-alcohol campaign between 1984 and 1987) (CitationLeon et al 1997; CitationBobak and Marmot 1999; CitationMcKee et al 2001). Several case-control and prospective studies have found that for a given level of total alcohol consumption, people who drink in binges rather than regularly tend to have higher rates of CHD (CitationKauhanen et al 1997b; CitationMcElduff and Dobson 1997; CitationRehm et al 2001; CitationMurray et al 2002) in addition to higher rates of other forms of cardiovascular disease (including sudden cardiac death) (CitationWannamethee and Shaper 1992; CitationKauhanen et al 1997a; CitationWood et al 1998). In a review article published in 1999, the importance of considering drinking pattern when considering the effects of alcohol on cardiovascular disease risk was highlighted (CitationPuddey et al 1999). The authors concluded that without proper understanding of the risks associated with different drinking patterns, public health advice regarding alcohol consumption would be limited in its scope and potentially flawed in its impact.

Choice of reference category

Most epidemiological studies of the effects of alcohol on CHD risk use nondrinkers as the reference category against which the effects of different levels of drinking are compared. However, if this group contains people who used to drink alcohol but have given up, any true benefits of alcohol consumption on risk are likely to become exaggerated. This is because ex-drinkers tend to exhibit several characteristics likely to increase their morbidity and mortality. In the British Regional Heart Study, ex-drinkers were found to have the highest prevalence of diagnosed CHD, diabetes, and bronchitis as well as the highest use of medication (CitationWannamethee and Shaper 1988). A high proportion smoked cigarettes, were of manual social class, were unmarried, and had measured hypertension and obesity. Similar characteristics among ex-drinkers have also been observed elsewhere (CitationFillmore et al 1998). While most epidemiological studies would tend to make attempts to take account of differences in the prevalence of risk factors and pre-existing disease in the different drinking groups (for instance, by excluding patients with known prior disease and making statistical adjustments for differences in the prevalence of risk factors) such corrections might only partially remove these effects. The proportion of nondrinkers comprising of ex-drinkers is also likely to vary considerably by population studied, and though for some countries this proportion may be small, for others the nondrinking category could become significantly contaminated by ex-drinkers (particular for older study populations). The overall bias this could introduce has been suggested by some to be small (CitationMaclure 1993), nonetheless it is clearly desirable for epidemiological studies of the effects of alcohol on health to be able to separate ex-drinkers from lifelong abstainers so as to examine these potential effects. In an updated 23-year report from the British Doctor's Study, for instance, ex-drinkers were separated from never drinkers. The study found that 2–3 units (16–24 g) of alcohol a day was associated with a reduction in CHD death of 28% (95% CI 12% to 42%) (CitationDoll et al 2005). However, it has been argued by some that lifelong abstainers should not provide the reference category for estimation of the health effects of alcohol consumption either (CitationWannamethee and Shaper 1997; CitationFillmore et al 1998). In countries where alcohol consumption is socially normal, lifelong abstainers often form a small and self-selected group and have been suggested to possess characteristics that could increase their risk of mortality, particularly from non-cardiovascular causes. Given the concerns regarding the suitability of nondrinkers (with or without first separating out ex-drinkers) to act as a valid reference group, a “low” active drinking exposure group (for instance people who drink only on special occasions) may provide a larger more reliable reference category on which to base risk comparisons. To illustrate the impact such a change in reference category could have, shows the relationship between alcohol intake and CHD risk estimated by a meta-analysis of 28 cohort studies (CitationCorrao et al 2004), and shows that if people who drink 1 g of alcohol a day are used as the reference category instead of nondrinkers, both the estimated benefits of moderate alcohol intake on CHD risk and the level at which alcohol causes notable harm are substantially reduced. While several studies now routinely use low active drinking groups as the reference category, many still use nondrinkers (often without first removing ex-drinkers) as their comparison group.

Reverse causality bias

Part of the concern over the use of nondrinkers as the reference category for alcohol–CHD association studies lies in the possibility that some people may give up alcohol because of ill health prior to enrolment into a study. If this ill health is CHD, reverse causality bias occurs, ie, pre-existing CHD causes a change in alcohol intake (rather than vice-versa), with the consequent risk that the high CHD incidence observed in this group is incorrectly attributed to their new level of drinking. Several studies have shown that after exclusion of people with prior CHD, the apparent benefits of light-to-moderate drinking (compared with nondrinking) are reduced (CitationShaper 1990; CitationLazarus et al 1991; CitationFarchi et al 1992). However, in a deductive meta-analysis published in 1993 (CitationMaclure 1993), this “sick quitter” hypothesis was refuted on the basis of contrary evidence from several very large cohort studies, including the Nurse's Health Study (CitationStampfer et al 1988), the American Cancer Society (CitationBoffetta and Garfinkel 1990), the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (CitationRimm et al 1991) and the Kaiser Permanente Study (CitationKlatsky et al 1990), all of which found the association between alcohol and CHD to be essentially unaffected by exclusion of ex-drinkers and people with chronic illness (though in the latter study it was noted that differences in total mortality between nondrinkers and drinkers may well be exaggerated by the presence of people with prior chronic illnesses in the nondrinking group; [CitationKlatsky et al 1990]).

Within-person variation in alcohol consumption

Almost all prospective studies of alcohol–CHD relationships use single baseline assessments of alcohol intake (usually ascertained by interview or questionnaire) in analyses. However, characterization of an individual's “exposure to alcohol” (irrespective of how this is actually defined) based on a single assessment may not accurately reflect that person's true long-term “usual” or “average” alcohol exposure throughout the duration of the study. Recall bias in alcohol intake, short-term deviations from a person's “normal” drinking habit at baseline, and long-term true changes in an individual's drinking habit (referred to as “within-person variation in alcohol exposure”) can lead to misclassification of individuals, which in turn can distort the true nature of the risk-relationship between “usual” alcohol exposure and CHD risk. Moreover, without knowing the nature of the misclassification (ie, whether it is random or systematic), one cannot predict whether the apparent “baseline” risk-relationship underestimates, overestimates, or even reverses the direction of the “true” risk-relationship. Nonetheless, many studies have reported associations between CHD risk and single measures of alcohol intake ascertained five, ten, or even twenty years earlier, with little, if any, discussion of the potential effect that within-person variation in alcohol exposure might have. However, by asking people about their alcohol intake at one or more follow-up assessments during a study, the nature and magnitude of this variation may be estimated and its effects explored. Several studies have either directly or indirectly assessed the effects of within-person variation in alcohol exposure in this way. In the British Doctors' Study, it was concluded that because a reasonable degree of consistency between alcohol intake at the beginning and end of the study was observed, their results would have been quite robust to the effects of within-person variation (CitationDoll et al 1994). Of the studies that have attempted to directly take account of within-person variation in alcohol exposure, most have used just two assessments of alcohol intake, and findings have been inconsistent (CitationFillmore et al 2003; CitationWellmann et al 2004). For example, in the Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease (MONICA)-Augsburg cohort, it was found that the estimated benefits of light alcohol consumption increased after taking the second measure of alcohol consumption into account (CitationWellmann et al 2004), while in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, no elevated mortality was observed when consistent never drinkers were compared with light drinkers (CitationFillmore et al 2003). In the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, assessment of alcohol intake every 4 years allowed examination of the effects of changes in alcohol consumption on the 12-year risk of myocardial infarction (MI). In this large American study, the beneficial effects of alcohol consumption on the risk of MI estimated using baseline measurements were found to be similar to estimates derived from analyses that fitted alcohol consumption as a “time-dependent” covariate (CitationMukamal et al 2003). However, three other large American studies have demonstrated that baseline measures of drinking groups may be particularly unreliable for younger samples, longer follow-up, and heavier drinkers (CitationKerr et al 2002). Recently, an analysis of the British Regional Heart Study demonstrated that by taking into account information on alcohol intake obtained after 5, 13, 17, and 20 years of follow-up (in addition to the information obtained at baseline), individuals could be categorized into exposure groups that were much better at predicting 20-year CHD risk than groups defined only from baseline information (CitationEmberson et al 2005). When compared with occasional drinking (defined as 1–2 times a month or on special occasions), the relative risk of CHD associated with heavy drinking increased from 1.08 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.35) to 1.44 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.72) when repeat information on alcohol intake was taken into account. This suggests that studies that relate CHD rates to single assessments of alcohol intake recorded many years earlier may systematically underestimate true risks associated with heavy drinking.

Confounding

We now come to a common problem that arises when interpreting any epidemiological study – the possibility for associations to be distorted because of confounding. Specifically, characteristics that are related both to alcohol consumption and to CHD risk have the potential to modify both the shape and magnitude of the true alcohol–CHD relationship. For instance, it is well recognized that regular light drinkers tend to exhibit a range of socioeconomic, behavioral, and physical characteristics which are advantageous to health. This was confirmed in a recent telephone survey of 200 000 adults in the US, in which 27 out of 30 cardiovascular risk factors were found to be significantly more prevalent among nondrinkers than light-to-moderate drinkers (CitationNaimi et al 2005). Observational studies attempt to take this into account by adjusting for these characteristics in statistical analyses. In the INTERHEART study of about 15 000 cases of MI and 15 000 controls from 52 countries, regular alcohol use (defined as 3 or more times per week) was associated with a 21% (95% CI 14% to 27%) reduction in MI risk after adjustment for age, sex and smoking, but only a 9% reduction after further adjustment for other coronary risk factors, though it should be recognised that this included factors likely to mediate the alcohol–MI relationship, eg, blood lipids (CitationYusuf et al 2004). Simple adjustment for measured levels of confounders may not remove all of the effects of confounding however. This is because confounders are typically measured only crudely, eg, cigarette smoking exposure may be recorded as current, ex, or never rather than in a more detailed manner that included type of cigarette smoked and pack-years smoked. Thus, even after “adjustment” for these characteristics, some of the remaining coronary benefit associated with light-to-moderate drinking in epidemiological studies may still be due to confounding (referred to as “residual confounding”). Nonetheless, it has been argued that the degree of consistency in the alcohol–CHD relationship that is observed across diverse populations reduces the likelihood that the benefits of light-to-moderate amounts of alcohol can be due entirely to confounding, leaving causality as the only remaining plausible explanation (CitationMarmot 1984; CitationMaclure 1993). Residual confounding among heavy drinkers also has the potential to explain some (perhaps all) of the coronary hazard associated with heavy drinking (since heavy drinkers tend to possess several harmful characteristics). The potential for this “bi-directional” confounding to occur (ie, confounding as a possible explanation both for the protective effect of alcohol among light drinkers and the harmful effect of alcohol among heavy drinkers), has led some to suggest that the coronary-protective effects of alcohol might actually only become apparent at moderate-to-heavy levels of drinking, and not light levels of drinking at all (CitationJackson et al 2005). Of course, any possible benefits on coronary risk from moderate-to-heavy levels of drinking would be greatly outweighed by increases in non-vascular risks (CitationCorrao et al 2004).

Study design and biases in the literature

Studies of the effect of alcohol on CHD risk tend to be either prospective cohort studies or case-control studies (though occasionally nested case-control designs are also used). Cohort studies have the intrinsic advantage over case-control studies that they should be less prone to reverse causality bias, since assessments of alcohol exposure are typically made before the onset of CHD. Case-control studies (though usually much more efficient than cohort studies in terms of time, money and effort) have the additional problems of finding an appropriately matched control group and ensuring that no recall biases in alcohol consumption are introduced (CitationSchulz and Grimes 2002). In particular, any differential biases in the recall of alcohol consumption between cases and controls could be especially problematic, having important implications for the estimation of risk-associations. In a meta-analysis of studies of the relationship between alcohol and CHD published between 1966 and 1998, significant differences were observed between the findings of cohort and case-control studies. Cohort studies typically observed lower protective effects of moderate alcohol consumption (CitationCorrao et al 2000). Another obstacle facing researchers who wish to provide an overview of the effects of alcohol on CHD risk is that there may be substantial publication bias in the literature. This became evident in the meta-analysis carried out by CitationCorrao et al (2000). Small studies reporting adverse effects of moderate drinking were found to be less likely to be published than small studies reporting beneficial (or no) effects of moderate alcohol consumption on CHD risk (CitationCorrao et al 2000). Finally, there may also be an intrinsic bias in the literature caused by the tendency of some authors to present and interpret their results in a way that best confirms their prior beliefs, though the effect of this potential source of bias is of course much more difficult to quantify.

Alcohol intake and stroke

Alcohol was first recognized as a possible risk factor for stroke in 1725. More recently, many epidemiological studies have studied the association between alcohol and stroke, generally finding, as for CHD, that light to moderate drinkers have a lower risk than abstainers, and heavy drinkers have increased risks. In a meta-analysis of 35 observational studies published between 1966 and 2002, which combined the results from 16 case-control and 19 prospective studies, drinking up to 12 g of alcohol a day was associated with a 17% (95% CI 9% to 35%) reduction in the risk of total stroke (compared with nondrinking), while drinking more than 60 g of alcohol a day was associated with a 64% (95% CI 39% to 93%) increase in the risk of stroke (CitationReynolds et al 2003).

To what extent might these associations be causally attributed to alcohol consumption? Many of the issues already discussed regarding the potential sources of bias in alcohol–CHD risk relationships apply equally for alcohol–stroke risk relationships. Thus, the apparent benefit of light-to-moderate drinking on total stroke risk observed in most populations could be due to residual confounding, contamination of the non-drinking group by ex-drinkers, or failure to take account of within-person variation in alcohol intake. In the British Regional Heart Study, for instance, taking within-person variation into account removed the apparent excess stroke risk experienced by nondrinkers (compared with occasional drinkers), and increased the relative risk of stroke for heavy drinkers relative to occasional drinkers from 1.54 (95% CI 1.06 to 2.22) to 2.33 (95% CI 1.46 to 3.71) (CitationEmberson et al 2005). In another study of ∼20 000 middle-aged Japanese men followed for 11 years (the Japan Public Health Center [JPHC] Study Cohort I [CitationIso et al 2004]), occasional and light drinkers (defined as <21 g/day) had the highest proportion of nonsmokers, the highest proportion of people who exercised at least once a week and the highest frequency of fruit intake, whereas people who drank at least 64 g of ethanol a day had the lowest proportions of each of these characteristics. Using occasional drinkers as the reference category, and taking differences in these confounders into account (as well as differences in BMI, education level, and history of diabetes) the risk of any stroke was found to increase linearly with alcohol intake to a relative risk of 1.55 (95% CI 1.11 to 2.15) amongst the heavy drinkers. These results were comparatively unaffected by “updating” alcohol intake using repeated information collected in 90% of people still alive after 5 years of follow-up.

Stroke sub-type and alcohol

In the JPHC study, stroke risk increased linearly with alcohol intake, apparently contradicting the U-shaped relationship observed in most cohort studies. However, if ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes are considered separately, the reason for this apparent discrepancy becomes evident. In most Western countries, approximately 70% to 80% of strokes occurring in middle-age are ischemic. Thus, the relationship between alcohol and total stroke in these populations generally reflects that observed with ischemic stroke. In the Physicians' Health Study, for instance, light and moderate drinking (1 drink/week and 2–4 drinks/week respectively) were found to be associated with reduced risks of ischemic stroke (relative risk [RR]=0.73 [0.52–1.00] and 0.74 [0.56–0.98] respectively), after adjustment for other stroke risk factors and compared with individuals who drank <1 drink/week, that were similar to those observed for all stroke (CitationBerger et al 1999). However, for hemorrhagic stroke, no significant association (in either direction) with alcohol intake was observed. Similarly, in the Nurses' Health Study of ∼87 000 female nurses, a decreased risk of ischemic stroke among those drinking moderate amounts of alcohol (1.5 g to 14.9 g per day) was observed (CitationStampfer et al 1988), but hemorrhagic stroke tended to be more common among this group than among the nondrinkers. In the JPHC study however, only around half of the strokes were ischemic. Separating strokes according to etiology, light-drinkers (<21 g per day) were found to have a reduced rate of ischemic stroke (RR=0.61 [0.39–0.97]) consistent with that observed in the American studies, while hemorrhagic stroke displayed a strong log-linear relationship with alcohol intake (RR=2.51 [1.43–4.41] for men who drank >64 g a day compared with occasional drinkers) (CitationIso et al 2004). Thus, the overall relationship between alcohol intake and stroke in the JPHC study was much more influenced by hemorrhagic stroke than is the case in most other studied populations. In a 2003 meta-analysis of alcohol and stroke (CitationReynolds et al 2003), 15 studies contained information on ischemic stroke and 12 contained information on hemorrhagic stroke. In these studies, people who drank less than 12 g of alcohol a day (equivalent to less than 1 drink per day) had the lowest risk of ischemic stroke (RR=0.80, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.91, compared with nondrinkers), while those who drank greater than or equal to 60 g a day had a RR of 1.69 (1.34–2.15). For hemorrhagic stroke however, a linear dose-response association was observed among people who drank any alcohol, with individuals who drank at least 60 g/day having a RR of 2.18 (95% CI 1.48 to 3.20) compared with nondrinkers. Subsequently, in another meta-analysis of observational studies looking at several different causes of mortality including ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, a non-statistically significant protective effect for ischemic stroke for alcohol intake of 25 g/day was observed when compared with nondrinkers. For hemorrhagic stroke, alcohol consumption of 25 g/day, 50 g/day, and 100 g/day was associated with RRs of 1.19 (0.97–1.49), 1.82 (1.46–2.28), and 4.70 (3.35–6.59) respectively, when compared with nondrinking. Again, the consistency in riskrelationships observed across different study designs in different populations strongly indicates that these alcohol–stroke relationships are, to some degree at least, causal. The question is, how?

Biological mechanisms

While there is an abundance of evidence to suggest that light-to-moderate alcohol intake protects against CHD as well as ischemic (but not hemorrhagic) stroke, evidence concerning the mechanisms by which these benefits are achieved has historically been more limited. General opinion now however agrees that alcohol consumption is likely to influence the risk of vascular disease primarily through beneficial effects on lipids and fibrinolytic activity (CitationRimm et al 1999), the effects of which are probably offset to some degree by adverse effects on blood pressure (CitationMarmot et al 1994).

Effect of alcohol on lipids and hemostatic factors

It is often stated that between 40% and 60% of the beneficial effect of light-to-moderate alcohol consumption on the risk of CHD is mediated through increases in HDL-C alone (CitationLanger et al 1992; CitationSuh et al 1992; CitationGaziano et al 1993; CitationMarques-Vidal et al 1996), with further benefits achieved through improvements in fibrinogen level and other clotting factors (CitationRimm et al 1999). In a case-control study of 340 patients with MI, for instance, the log relative risk of MI associated with drinking more than 3 drinks a day compared with drinking less than 1 drink a month was attenuated by 60% after adjustment solely for the levels of the HDL2 and HDL3 subfractions (CitationGaziano et al 1993). In the Nurses' Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, nested case-control studies of alcohol and MI risk showed that at least 75% (higher in men) of the benefit associated with frequent drinking (defined as at least 3 to 4 days per week) and MI risk could be explained by advantageous levels of HDL-C, fibrinogen and hemoglobin A1c among the frequent drinkers (CitationMukamal et al 2005). Large population-based studies have confirmed alcohol consumption to be related to beneficial levels of HDL-C and fibrinogen (CitationWannamethee et al 2003; CitationSchroder et al 2005), while genetic association studies of the alcohol dehydrogenase type 3 (ADH3) polymorphism further support a causal effect of alcohol on CHD risk that is mediated by HDL-C (CitationHines et al 2001; CitationDavey Smith and Ebrahim 2003). In a meta-analysis of experimental studies investigating the effects of alcohol consumption on blood lipids and haemostatic factors in people with no prior history of chronic disease and no history of alcohol dependence, 30 g of ethanol per day was estimated to increase HDL-C by 3.99 mg/dL, increase apolipoprotein A1 by 8.82 mg/dL and decrease fibrinogen by 7.5 mg/dL, but also to increase triglycerides of 5.69 mg/dL. The authors predicted that through its effects on these four biological markers, 30 g of ethanol a day would be expected (from epidemiological studies) to reduce the risk of CHD by 25% (CitationRimm et al 1999). The effect of moderate alcohol consumption on HDL-C would also be expected to lead to a reduction in ischemic, but not hemorrhagic, stroke. However, the anticoagulant effects of alcohol, though beneficial for ischemic stroke, may play an important role in increasing the risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Effect of alcohol on blood pressure

Though alcohol has some favorable effects on blood lipids and hemostatic factors, it also increases blood pressure, one of the most important determinants of cardiovascular disease risk (CitationPSC 2002). In 1994, the International Study of Electrolyte Excretion and Blood Pressure (INTERSALT), a study designed to investigate the relations between salt and blood pressure in 50 centres worldwide, presented data on alcohol and blood pressure (CitationMarmot et al 1994). As well as ascertaining whether the total amount of alcohol consumed was related to blood pressure, the study investigated whether different patterns of alcohol consumption might have differential influences on blood pressure level. Results showed that heavy alcohol intake (≥300 ml/week [34 g/day]) was related to both higher systolic blood pressure (SBP) and higher diastolic blood pressure (DBP) levels: in men, mean blood pressure (SBP/DBP) was 2.7/1.6 mm Hg higher among heavy drinkers than among nondrinkers; this figure was 3.9/3.1 mm Hg in women. Furthermore, differences in blood pressure between drinkers and nondrinkers were found to be greater among “episodic drinkers” (people with the highest daily variation in alcohol consumption) than among people who drank a regular amount of alcohol each day. Similar adverse effects of binge drinking on blood pressure level (independent of amount of alcohol consumed) have also been observed elsewhere (CitationStranges et al 2004). In a recent meta-analysis of epidemiological studies which looked at the association of alcohol consumption with the risk of 15 diseases, alcohol at doses of 25 g/day, 50 g/day, and 100 g/day were associated with relative risks of hypertension of 1.43 (95% CI 1.33–1.53), 2.04 (1.77–2.35) and 4.15 (3.13–5.52) respectively (when compared with individuals who did not drink alcohol) (CitationCorrao et al 2004). In another meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of alcohol reduction, reducing alcohol intake by an average of 67% (from 3–6 drinks per day to 1–2 drinks per day) reduced SBP by 3.3 mm Hg and DBP by 2.0 mm Hg (CitationXin et al 2001). Though relatively small, long-term differences in blood pressure of this magnitude can have important effects on the risk of CHD and, particularly, stroke. Using estimates of the relations between usual blood pressure and the risk of CHD and stroke mortality from the Prospective Studies Collaboration of one million individuals from 61 prospective studies, it can be calculated that during middle-age (40–59 years) a difference in SBP of 3.3mm Hg is associated with an approximate 12% higher risk of fatal CHD and 19% higher risk of fatal stroke (similar for both ischemic and hemorrhagic), while a 2.0 mm Hg higher DBP level is associated with a 16% higher risk of fatal CHD and 23% higher risk of fatal stroke (CitationPSC 2002).

Summary

The consistency of the relationship between light-to-moderate alcohol intake and reduced risks of CHD, together with the existence of plausible biological mechanisms, strongly suggests that moderate alcohol consumption does reduce CHD risk. However, the true magnitude of benefit at any given level may be lower than suggested by most observational studies (mainly because of the difficulties in removing confounding from comparisons as well as the problems caused by the use of nondrinkers as the reference group). Drinking pattern (specifically, drinking with meals) may also have as much influence on reducing CHD risk as overall alcohol amount, though there is little reliable evidence to indicate that any particular type of drink is more or less beneficial than any other. Heavy drinking is associated with increased CHD risk, but the degree that this may be causal is uncertain because while previous studies may have systematically underestimated the risks by not taking within-person variation into account, the observed hazards could also be due to residual confounding. For stroke, the observed relationship between alcohol consumption and risk in a given population depends on the proportion of strokes that are hemorrhagic. Light-to-moderate alcohol intake is associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke which is likely to be, in part, causal. Hemorrhagic stroke, on the other hand, displays a loglinear relationship with alcohol intake.

In conclusion, drinking 20 g to 30 g of alcohol a day probably reduces major vascular risk in middle-aged people by up to one fifth. However, given that alcohol intake displays clear positive relationships with total mortality in younger people (as well as positive relationships with nonvascular causes of death in middle-aged people), considerable caution in making any general statements about safe levels of alcohol consumption is needed. In particular, any policy that resulted in an overall increase in population average alcohol consumption would be likely to do substantially more harm than good.

References

- BeagleholeRJacksonRAlcohol, cardiovascular disease and all causes of death: a review of the epidemiological evidenceDrug Alcohol Rev1992111758916840273

- BergerKAjaniUAKaseCSLight-to-moderate alcohol consumption and risk of stroke among U.S. male physiciansN Engl J Med199934115576410564684

- BobakMMarmotMAlcohol and mortality in Russia: is it different than elsewhere?Ann Epidemiol19999335810475531

- BobakMSkodovaZMarmotMEffect of beer drinking on risk of myocardial infarction: population based case-control studyBMJ20003201378910818027

- BoffettaPGarfinkelLAlcohol drinking and mortality among men enrolled in an American Cancer Society prospective studyEpidemiology1990134282078609

- CorraoGBagnardiVZambonAA meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseasesPrev Med2004386131915066364

- CorraoGRubbiatiLBagnardiVAlcohol and coronary heart disease: a meta-analysisAddiction20009515052311070527

- Davey SmithGEbrahimS‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease?Int J EpidemioI200332122

- Di-CastelnuovoARotondoSIacovielloLMeta-analysis of wine and beer consumption in relation to vascular riskCirculation200210528364412070110

- DollRPetoRBorehamJMortality in relation to alcohol consumption: a prospective study among male British doctorsInt J Epidemiol20053419920415647313

- DollRPetoRHallEMortality in relation to consumption of alcohol: 13 years' observations on male British doctorsBMJ1994309911187950661

- EmbersonJRShaperAGWannametheeSGAlcohol intake in middle age and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: accounting for intake variation over timeAm J Epidemiol20051618566315840618

- FarchiGFidanzaFMariottiSAlcohol and mortality in the Italian rural cohorts of the Seven Countries StudyInt J Epidemiol19922174811544762

- FillmoreKMGoldingJMGravesKLAlcohol consumption and mortality. I. Characteristics of drinking groupsAddiction1998931832039624721

- FillmoreKMKerrWCBostromAChanges in drinking status, serious illness and mortalityJ Stud Alcohol2003642788512713203

- FleschMSchwarzABohmMEffects of red and white wine on endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation of rat aorta and human coronary arteriesAm J Physiol1998275H1183909746465

- FoppaMFuchsFDPreisslerLRed wine with the noon meal lowers post-meal blood pressure: a randomized trial in centrally obese, hypertensive patientsJ Stud Alcohol2002632475112033702

- FrankelENKannerJGermanJBInhibition of oxidation of human low-density lipoprotein by phenolic substances in red wineLancet199334145478094487

- FuchsCSStampferMJColditzGAAlcohol consumption and mortality among womenN Engl J Med19953321245507708067

- GazianoJMBuringJEBreslowJLModerate alcohol intake, increased levels of high-density lipoprotein and its subfractions, and decreased risk of myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med19933291829348247033

- GronbaekMBeckerUJohansenDType of alcohol consumed and mortality from all causes, coronary heart disease, and cancerAnn Int Med20001334111910975958

- HendriksHFVeenstraJVelthuis-te WierikEJEffect of moderate dose of alcohol with evening meal on fibrinolytic factorsBMJ1994308100368167511

- HinesLMStampferMJMaJGenetic variation in alcohol dehydrogenase and the beneficial effect of moderate alcohol consumption on myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med20013445495511207350

- IijimaKYoshizumiMOuchiYEffect of red wine polyphenols on vascular smooth muscle cell function—molecular mechanism of the ‘French paradox’Mech Ageing Dev20021231033912044952

- IsoHBabaSMannamiTAlcohol consumption and risk of stroke among middle-aged men: the JPHC Study Cohort IStroke2004351124915017008

- JacksonRBroadJConnorJAlcohol and ischaemic heart disease: probably no free lunchLancet200536619111216325685

- KauhanenJKaplanGAGoldbergDDFrequent hangovers and cardiovascular mortality in middle-aged menEpidemiology1997a8310149115028

- KauhanenJKaplanGAGoldbergDEBeer binging and mortality: results from the Kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study, a prospective population based studyBMJ1997b315846519353504

- KeilUChamblessLEDoringAThe relation of alcohol intake to coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality in a beer-drinking populationEpidemiology1997815069229206

- KerrWCFillmoreKMBostromAStability of alcohol consumption over time: evidence from three longitudinal surveys from the United StatesJ Stud Alcohol2002633253312086133

- KlatskyALArmstrongMAFriedmanGDRisk of cardiovascular mortality in alcohol drinkers, ex-drinkers and non-drinkersAm J Cardiol1990661237422239729

- LangerRDCriquiMHReedDMLipoproteins and blood pressure as biological pathways for effect of moderate alcohol consumption on coronary heart diseaseCirculation199285910151537127

- LazarusNBKaplanGACohenRDChange in alcohol consumption and risk of death from all causes and from ischaemic heart diseaseBMJ199130355361912885

- LeonDAChenetLShkolnikovVMHuge variation in Russian mortality rates 1984-94: artefact, alcohol, or what?Lancet199735038389259651

- LindenstromEBoysenGNyboeJInfluence of total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides on risk of cerebrovascular disease: the Copenhagen City Heart StudyBMJ199430911158044059

- MaclureMDemonstration of deductive meta-analysis: ethanol intake and risk of myocardial infarctionEpidemiol Rev199315328518174661

- MarmotMGAlcohol and coronary heart diseaseInt J Epidemiol19841316076376385

- MarmotMGElliottPShipleyMJAlcohol and blood pressure: the INTERSALT studyBMJ1994308126377802765

- Marques-VidalPDucimetierePEvansAAlcohol consumption and myocardial infarction: a case-control study in France and Northern IrelandAm J Epidemiol19961431089938633596

- McElduffPDobsonAJHow much alcohol and how often? Population based case-control study of alcohol consumption and risk of a major coronary eventBMJ19973141159649146388

- McKeeMShkolnikovVLeonDAAlcohol is implicated in the fluctuations in cardiovascular disease in Russia since the 1980sAnn Epidemiol2001111611164113

- MukamalKJConigraveKMMittlemanMARoles of drinking pattern and type of alcohol consumed in coronary heart disease in menN Engl J Med20033481091812519921

- MukamalKJJensenMKGronbaekMDrinking frequency, mediating biomarkers, and risk of myocardial infarction in women and menCirculation200511214061316129796

- MurrayRPConnettJETyasSLAlcohol volume, drinking pattern, and cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: is there a U-shaped function?Am J Epidemiol2002155242811821249

- NaimiTSBrownDWBrewerRDCardiovascular risk factors and confounders among nondrinking and moderate-drinking U.S. adultsAm J Prev Med2005283697315831343

- Pace-AsciakCRHahnSDiamandisEPThe red wine phenolics trans-resveratrol and quercetin block human platelet aggregation and eicosanoid synthesis: implications for protection against coronary heart diseaseClin Chim Acta1995235207197554275

- [PSC] Prospective Studies CollaborationAge-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studiesLancet200236019031312493255

- PuddeyIBRakicVDimmittSBInfluence of pattern of drinking on cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors—a reviewAddiction1999946496310563030

- RehmJGreenfieldTKRogersJDAverage volume of alcohol consumption, patterns of drinking, and all-cause mortality: results from the US National Alcohol SurveyAm J Epidemiol2001153647111159148

- RenaudSde LorgerilMWine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart diseaseLancet1992339152361351198

- ReynoldsKLewisBNolenJDAlcohol consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysisJAMA20032895798812578491

- RimmEBGiovannucciELWillettWCProspective study of alcohol consumption and risk of coronary disease in menLancet199133846481678444

- RimmEBKlatskyAGrobbeeDReview of moderate alcohol consumption and reduced risk of coronary heart disease: is the effect due to beer, wine, or spiritsBMJ199631273168605457

- RimmEBWilliamsPFosherKModerate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factorsBMJ19993191523810591709

- SacksFMThe role of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease: expert group recommendationsAm J Cardiol2002901394312106843

- SchroderHFerrandezOJimenez CondeJCardiovascular risk profile and type of alcohol beverage consumption: a populationbased studyAnn Nutr Metab200549100615809497

- SchulzKFGrimesDACase-control studies: research in reverseLancet2002359431411844534

- ShaperAGAlcohol and mortality: a review of prospective studiesBr J Addict19908583747 discussion 849-612204454

- StampferMJColditzGAWillettWCA prospective study of moderate alcohol consumption and the risk of coronary disease and stroke in womenN Engl J Med1988319267733393181

- StrangesSWuTDornJMRelationship of alcohol drinking pattern to risk of hypertension: a population-based studyHypertension2004448131915477381

- SuhIShatenBJCutlerJAAlcohol use and mortality from coronary heart disease: the role of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. The Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research GroupAnn Int Med199211688171580443

- TanneDYaariSGoldbourtUHigh-density lipoprotein cholesterol and risk of ischemic stroke mortality. A 21-year follow-up of 8586 men from the Israeli Ischemic Heart Disease StudyStroke1997288378996494

- TheobaldHBygrenLOCarstensenJA moderate intake of wine is associated with reduced total mortality and reduced mortality from cardiovascular diseaseJ Stud Alcohol200061652611022802

- ThunMJPetoRLopezADAlcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly U.S. adultsN Engl J Med19973371705149392695

- TrevisanMDornJFalknerKDrinking pattern and risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction: a population-based case-control studyAddiction2004993132214982544

- TrevisanMSchistermanEMennottiADrinking pattern and mortality: the Italian risk factor and life expectancy pooling projectAnn Epidemiol2001113121911399445

- VeenstraJOckhuizenTvan de PolHEffects of a moderate dose of alcohol on blood lipids and lipoproteins postprandially and in the fasting stateAlcohol Alcohol19902537172121150

- WannametheeGShaperAGMen who do not drink: a report from the British Regional Heart StudyInt J Epidemiol198817307163403125

- WannametheeGShaperAGAlcohol and sudden cardiac deathBr Heart J19926844381467026

- WannametheeSGLoweGDShaperGThe effects of different alcoholic drinks on lipids, insulin and haemostatic and inflammatory markers in older menThromb Haemost2003901080714652640

- WannametheeSGShaperAGLifelong teetotallers, ex-drinkers and drinkers: mortality and the incidence of major coronary heart disease events in middle-aged British menInt J Epidemiol199726523319222777

- WannametheeSGShaperAGType of alcoholic drink and risk of major coronary heart disease events and all-cause mortalityAm J Public Health1999896859010224979

- WannametheeSGShaperAGEbrahimSHDL-Cholesterol, total cholesterol, and the risk of stroke in middle-aged British menStroke2000311882810926951

- WellmannJHeidrichJBergerKChanges in alcohol intake and risk of coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality in the MONICA/KORA-Augsburg cohort 1987-97Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil200411485515167206

- WoodDDe BackerGFaergemanOPrevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice: recommendations of the Second Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Coronary PreventionAtherosclerosis19981401992709862269

- XinXHeJFrontiniMGEffects of alcohol reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsHypertension20013811121711711507

- YusufPSHawkenSOunpuuSEffect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control studyLancet20043649375215364185