Abstract

Olmesartan medoxomil is an angiotensin II receptor antagonist. In pooled analyses of seven randomized, double-blind trials, 8 weeks’ treatment with olmesartan medoxomil was significantly more effective than placebo in terms of the response rate, proportion of patients achieving target blood pressure (BP) and mean change from baseline in diastolic (DBP) and systolic blood pressure (SBP). Olmesartan medoxomil had a fast onset of action, with significant between-group differences evident from 2 weeks onwards. The drug was well tolerated with a similar adverse event profile to placebo. In patients with type 2 diabetes, olmesartan medoxomil reduced renal vascular resistance, increased renal perfusion, and reduced oxidative stress. In several large, randomized, double-blind trials, olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg has been shown to be significantly more effective, in terms of primary endpoints, than recommended doses of losartan, valsartan, irbesartan, or candesartan cilexetil, and to provide better 24 h BP protection. Olmesartan medoxomil was at least as effective as amlodipine, felodipine and atenolol, and significantly more effective than captopril. The efficacy of olmesartan medoxomil in reducing cardiovascular risk beyond BP reduction is currently being investigated in trials involving patients at high risk due to atherosclerosis or type 2 diabetes.

Introduction

Individuals with hypertension are at a significantly greater risk of morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease. The largest study of the effects of hypertension on cardiovascular risk comes from analysis of data from more than one million adults who had no known baseline cardiovascular disease. This meta-analysis revealed a linear relationship between cardiovascular risk and increasing systolic blood pressure (SBP) in which each increase of 20 mmHg in SBP was associated with a doubling of cardiovascular risk in patients aged 40–60 (CitationLewington et al 2002). More recently, the INTERHEART study has demonstrated that hypertension is one of the most potent predictors of myocardial infarction (CitationYusuf et al 2004).

The benefits of BP reduction in reducing morbidity and mortality in conditions associated with hypertension have been clearly shown. In clinical trials, treating hypertension reduced the incidence of stroke by 35%–40%, myocardial infarction by 20%–25%, and heart failure by >50% (CitationChobanian et al 2003). Thus, in patients with uncomplicated hypertension, the minimal goal of therapy is a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of <140 mmHg and a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of <90 mmHg (CitationChobanian et al 2003) or <80 mmHg (CitationESH–ESC 2003). In hypertensive patients with diabetes or renal disease, the goals are <80 mmHg and <130 mmHg.

Angiotensin II is a potent vasoconstrictor and the primary effector of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS), which plays a central role in the regulation of BP (CitationBrunner et al 1993). Evidence suggests that increased angiotensin II levels are an independent risk factor for cardiac disease (CitationBrunner 2001). Thus, the development of treatments like angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, which inhibit the activity of the RAS, provided an effective approach to the treatment of hypertension. However, ACE inhibitors are associated with various adverse effects such as cough and angioedema (CitationFletcher et al 1994; CitationVleeming et al 1998) and further research and clinical development has led to the development of highly specific angiotensin II receptor antagonists.

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists inhibit the RAS at the level of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor, thereby providing effective antihypertensive efficacy without the side effects associated with ACE inhibitors. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists have proven efficacy in treating hypertension (CitationBurnier and Brunner 2000), and a tolerability profile similar to placebo (CitationMazzolai and Burnier 1999). Furthermore, the initial use of one of these agents has been shown to increase long-term patient persistence rates compared with those for patients initially prescribed ACE inhibitors, calcium channel antagonists, beta-blockers, or thiazide diuretics (CitationConlin et al 2001).

Olmesartan medoxomil is a nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonist that selectively and competitively inhibits the type 1 angiotensin II receptor (CitationMizuno et al 1995). Olmesartan medoxomil is administered once daily for the treatment of hypertension (CitationNussberger and Koike 2004). The agent has low potential for interaction with other drugs, and has been shown to be at least as effective as a number of other commonly used antihypertensive drugs. This article reviews the use of olmesartan medoxomil as monotherapy in patients with hypertension.

Pharmacological properties

Pharmacodynamics

Olmesartan medoxomil is a nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonist. The drug acts by selectively blocking angiotensin II type 1 receptor sites in vascular smooth muscle, thereby inhibiting the vasoconstrictor effects of angiotensin II. In salt-restricted hypertensive adults, a single dose of olmesartan medoxomil lowered mean 24 h ambulatory BP and increased renin and angiotensin II concentrations in the plasma (CitationPuchler et al 1997).

In bovine cerebellar membranes, olmesartan competitively inhibited binding of [125I]-angiotensin II to angiotensin II type 1 receptors, but not to type 2 receptors (CitationMizuno et al. 1995). Olmesartan and the active metabolite of losartan (EXP3174) both antagonized contraction induced by angiotensin II in a dose-dependent manner in guinea pig aortic tissue. However, olmesartan medoxomil 0.3 nmol/L inhibited approximately 90% of the contractile response, whereas the same concentration of EXP3174 inhibited contraction by approximately 35%. The inhibitory effects of olmesartan and EXP3174 lasted for <90 and <60 minutes, respectively (CitationMizuno et al 1995).

In rats, olmesartan medoxomil inhibited the angiotensin II-induced pressor response (CitationMizuno et al 1995; CitationKoike et al 2001), and prevented production of markers of early cardiovascular inflammation (CitationUsui et al 2000), myocardial remodeling (CitationTakemoto et al 1997), and cardiac fibrosis (CitationTomita et al 1998) induced by inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis. Olmesartan medoxomil also reduced urinary protein excretion in a dose-dependent fashion in Zucker diabetic fatty rats (CitationKoike 2001) and spontaneously hypertensive rats (CitationKoike et al 2001). In animal models of atherosclerosis, olmesartan medoxomil has been shown to reduce the area of aortic plaque lesions and to reduce intimal thickening in cross sections of the aorta (CitationKoike 2001; CitationKoike et al 2001).

Pharmacokinetics

Olmesartan medoxomil is a prodrug that is rapidly hydrolyzed into olmesartan in the gastrointestinal tract. Olmesartan is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract into the body, with a maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of 0.22–2.1 mg/L and time to Cmax of 1.4–2.8 h following administration of olmesartan medoxomil 10–160 mg (CitationSchwocho and Masonson 2001). For the same doses, the mean area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) was 1.6–19.9 mgh/L.

Olmesartan is the only metabolite of olmesartan medoxomil, and is excreted in the feces (~60%) and the urine. Following the administration of olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg to healthy volunteers, the mean terminal elimination half-life was 12–18 h (CitationSchwocho and Masonson 2001). This relatively long half-life means angiotensin II type 1 receptor binding can be achieved with once-daily administration (CitationWehling 2004), which compares favorably with the half-lives of some other angiotensin II receptor antagonists: irbesartan (11–15 h), losartan (2 h) and its active metabolite (4–5 h), and valsartan (6 h).

Although the AUC increased in elderly patients, and the AUC and Cmax increased and renal clearance decreased in patients with renal impairment, dosage adjustment should not be necessary in elderly patients or those with mild-to-moderate renal impairment (CitationBrunner 2002).

Olmesartan is not metabolized by cytochrome P-450 enzymes and is therefore unlikely to interact with drugs that inhibit, induce, or are metabolized by cytochrome P-450 enzymes (CitationWehling 2004). In drug interaction studies, there were no clinically significant effects on the pharmacokinetic properties of either drug when olmesartan medoxomil was coadministered with warfarin, digoxin, or aluminum magnesium hydroxide (CitationWehling 2004).

Clinical trials

Placebo-controlled trials

The efficacy of olmesartan medoxomil compared with placebo in adults with mild-to-moderate essential hypertension has been reviewed previously in pooled analyses (CitationNeutel 2001; CitationPuchler et al 2001; CitationBrunner 2004). These analyses included 7 randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase II or III trials, conducted in the US or EU. All studies included placebo run-in periods and were of a duration of at least 8 weeks. Studied doses ranged from 2.5 mg to 80 mg; this review will focus on the doses recommended in the EU: 10 mg (starting dose), 20 mg (optimal dose), and 40 mg (maximum dose). The primary endpoints were as follows: the proportion of patients achieving a sitting DBP response (sitting DBP ≥90 mmHg or reduced by ≤10 mmHg from baseline); the proportion of patients achieving a target sitting DBP of ≤90 mmHg; and the change from baseline in mean sitting DBP (CitationNeutel 2001; CitationPuchler et al 2001). Efficacy analyses included all patients who received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one follow-up measurement of any efficacy variable.

A total of 3055 patients were randomized to treatment. Of these, 544 received placebo and 522, 562, and 195 received olmesartan medoxomil 10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg, respectively. At baseline, the mean sitting DBP and SBP were approximately 104 mmHg and 160 mmHg (CitationNeutel 2001; CitationSankyo Pharma GmbH 2002). The mean age of patients was ~55 years (range 22–92); with the majority of patients aged <65 years (80%) and Caucasian (87–88%) (CitationPuchler et al 2001).

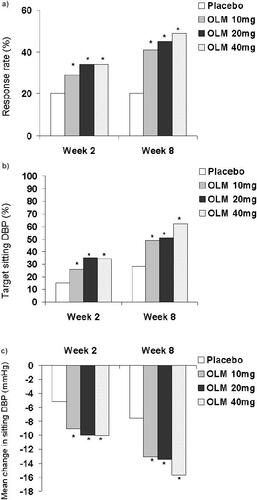

After treatment for 8 weeks, olmesartan medoxomil was significantly more effective than placebo in terms of the proportion of patients achieving target sitting DBP, and the mean change from baseline in sitting DBP (). Significant differences between olmesartan medoxomil and placebo in these endpoints were observed from the first assessment (week 2) onwards () (CitationSankyo Pharma GmbH 2002).

Figure 1 Efficacy of olmesartan medoxomil (OLM) at 2- (CitationSankyo Pharma GmbH 2002) and 8- (CitationPuchler et al 2001) weeks in a pooled analysis of 7 placebo-controlle-dtrials: primary efficacy endpoints.

a) The proportion of patients achieving a target sitting systolic blood pressure ≤140 mmHg

b) The proportion of patients achieving a target sitting dystolic blood pressure (DBP) of ≤90 mmHg.

c) Mean change from baseline in sitting DBP.

The proportions of placebo and olmesartan medoxomil 10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg recipients who achieved target sitting SBP ≤140 mmHg were 20%, 29%, 34%, and 34% after treatment for 2 weeks (CitationSankyo Pharma GmbH 2002) and 20%, 41%, 45%, and 49% after treatment for 8 weeks (CitationPuchler et al 2001) (p <0.001 vs placebo) (). The mean reduction in sitting SBP after two weeks was 4.62 mmHg for placebo recipients, compared with 11.55 mmHg, 12.55 mmHg, and 13.08 mmHg for olmesartan medoxomil 10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg recipients (p <0.001) (CitationSankyo Pharma GmbH 2002). Respective reductions after treatment for 8 weeks were 6.76 mmHg compared with 15.99 mmHg, 16.94 mmHg, and 20.65 mmHg (p <0.001) (CitationPuchler et al 2001).

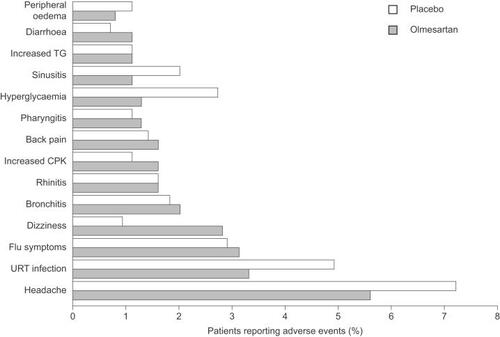

All doses of olmesartan medoxomil were well tolerated, with a similar adverse event profile to placebo and no apparent dose-related trends () (CitationPuchler et al. 2001). The majority of events were mild or moderate in severity. Seven adverse events were pre-defined as being of special interest (headache, cough, angioedema, hypotension, hyperkalemia, gastrointestinal disorders, and liver and biliary function disorders). The most common adverse event was headache, which was experienced by more (numerically) placebo than olmesartan medoxomil recipients (). No patients experienced angioedema, while hypotension and hyperkalemia were very rare (). Slightly more olmesartan medoxomil than placebo recipients experienced gastrointestinal-related disorders, while the incidence of liver and biliary function disorders was similar across the groups (). Other common adverse events included upper-respiratory tract infection, influenza-like symptoms, bronchitis, and dizziness, all of which were experienced by similar proportions of patients in the placebo and olmesartan medoxomil groups. There were no clinically significant changes in any of the laboratory variables assessed.

Table 1 Tolerability of olmesartan medoxomil 10 mg, 20 mg and 40 mg compared with placebo in a pooled analysis of 7 randomized, double-blind, multicenter trials: percentage of patients experiencing adverse events (AEs) (CitationPuchler et al 2001)

Target organ protection

In patients with diabetes, increased renal and intra-renal activity of the RAS can contribute to the development of diabetic renal damage by increasing renovascular resistance and intraglomerular pressure. The effects of angiotensin II receptor blockade on renal hemodynamics in patients with type 2 diabetes have been studied in a randomized, placebo-controlled study involving olmesartan. When normotensive or hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes received olmesartan medoxomil 40 mg (n=19) or placebo (n=16) for 12 weeks olmesartan medoxomil decreased renal vascular resistance, increased renal perfusion and reduced oxidative stress (CitationFliser et al 2005). In addition to significantly reducing mean ambulatory 24 h, daytime, and nighttime DBP and SBP from baseline, olmesartan medoxomil significantly (p<0.05) increased renal plasma flow (from 602–628 mL/min/1.73 m2) and decreased filtration fraction and renovascular resistance. Plasma concentrations of 8-isoprostane 15(S)-8-prostaglandin F2a, a biochemical marker of oxidative stress, also decreased significantly with olmesartan medoxomil (p<0.05). In contrast, patients who received placebo showed no significant effect on BP, a significant decrease in renal plasma flow and increase in filtration fraction (p<0.05), and a non-significant increase in renovascular resistance. In patients with type 2 diabetes, such changes in renal hemodynamics and oxidative stress may contribute to the beneficial long-term renal effects of angiotensin II blockade with agents such as olmesartan medoxomil.

Patients with hypertension frequently suffer from other conditions that increase their risk of cardiovascular disease, such as atherosclerosis. Chronic vascular inflammation is believed to play a major role in atherosclerosis and the EUropean Trial on Olmesartan and Pravastatin in Inflammation and Atherosclerosis (EUTOPIA) set out to investigate the effects of olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg on markers of vascular inflammation. In this double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study, patients with essential hypertension and signs of vascular microinflammation were randomly allocated to treatment with olmesartan medoxomil (n=100) or placebo (n=99) for 12 weeks (CitationFliser et al 2004). After 6 weeks, all patients also received once-daily pravastatin 20 mg. After treatment for 6 weeks, olmesartan medoxomil reduced serum levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), a strong predictor of cardiovascular events, by 15% from baseline (p<0.05). Olmesartan medoxomil also significantly reduced levels of high-sensitivity tumor necrosis factor-α (hsTNF-α) by 8.9% (p<0.02), interleukin-6 (IL-6) by 14.0% (p<0.05) and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 by 6.5% (p<0.01). In contrast, there were no major changes in the placebo (ie, BP reduction) group. At the end of the trial, olmesartan medoxomil plus pravastatin, but not placebo plus pravastatin, had further reduced levels of hsCRP (21.1%, p<0.01), hsTNF-α (13.6%, p<0.01), and IL-6 (18.0%, p<0.01). These anti-inflammatory changes indicate that olmesartan medoxomil, in addition to its BP-lowering effects, may produce beneficial effects on atherosclerosis and thus on overall cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertension who have atherosclerosis, or are at risk of developing it.

Comparative trials with olmesartan medoxomil

Versus other angiotensin II receptor antagonists

The first study to evaluate the comparative efficacy and tolerability of olmesartan medoxomil with another angiotensin II receptor antagonist was a double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study in which 316 patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension (DBP 95–114 mmHg) were treated with either olmesartan medoxomil or losartan for 12 weeks. After 2, 4, and 12 weeks, DBP showed significantly greater reductions with olmesartan medoxomil (8.4 mmHg, 9.1 mmHg, 10.6 mmHg, respectively) than with losartan (6.2 mmHg, 6.4 mmHg, 8.5 mmHg, respectively; 95% confidence index [CI] below zero). The changes in SBP at these time points were also significantly greater with olmesartan 10mg once daily (12.1 mmHg, 13.0 mmHg, 14.9 mmHg) than with losartan 50 mg once daily (7.6 mmHg, 9.5 mmHg, 11.6 mmHg, 95% CI below zero). The proportion of responders (DBP <90 mmHg and/or reduced by ≥10 mmHg from baseline) was also significantly greater with olmesartan medoxomil than losartan at weeks 2 (45% vs 30%, respectively p<0.01) and 4 (54% vs 32%, respectively p<0.01), and numerically greater at week 12 (63% vs 52%, respectively) (CitationStumpe and Ludwig 2002; CitationStumpe 2004).

The efficacy of olmesartan medoxomil has also been compared with other angiotensin II receptor antagonists in two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trials (CitationOparil et al 2001; CitationBrunner et al 2003) which had either a 2- (CitationBrunner et al 2003) or 4-week (CitationOparil et al 2001) placebo run-in period before treatment. In the trial reported by CitationOparil and colleagues (2001), 588 patients with a mean cuff DBP of 100–115 mmHg and ambulatory daytime DBP ≥90 mmHg and <120 mmHg were randomized to receive once-daily olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg or losartan (50 mg), valsartan (80 mg) or irbesartan (150 mg; at the time that this study was initiated, these were the recommended starting doses for each agent) (CitationOparil et al 2001) After treatment for 8 weeks, olmesartan medoxomil reduced the mean sitting cuff DBP (primary endpoint) from baseline by significantly more than losartan, valsartan, or irbesartan (); significant between-group differences in this endpoint were observed from the first assessment point (2 weeks) onwards. Although olmesartan medoxomil reduced the mean sitting cuff SBP numerically more than the other agents, these differences did not reach statistical significance (). The mean ambulatory 24 h DBP was reduced significantly more in the olmesartan medoxomil group than the losartan, valsartan or irbesartan groups (). Olmesartan medoxomil also reduced the mean ambulatory 24h SBP, daytime DBP and SBP, and nighttime SBP by significantly more than losartan or valsartan, and the mean ambulatory nighttime DBP by significantly more than valsartan ().

Table 2 Mean reduction from baseline in cuff and ambulatory blood pressure (mmHg) after 8 weeks of treatment with angiotensin II receptor blockers in two multicenter, double-blind trails. In the CitationOparil et al (2001) trial, the mean cuff dystolic blood pressure (DBP) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) values at baseline were 104 mmHg and 155–C157 mmHg. In the CitationBrunner et al (2003) study, the mean ambulatory daytime DBP and SBP were ≈95 mmHg and ≈149 mmHg at baseline

The trial by CitationBrunner and colleagues (2003) compared once-daily olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg with candesartan cilexetil 8 mg in 635 patients with a trough mean sitting DBP of 100–120 mmHg and SBP >150 mmHg after withdrawal of existing antihypertensive agents (CitationBrunner et al 2003). After treatment for 8 weeks, olmesartan medoxomil recipients had a significantly greater reduction from baseline in mean ambulatory daytime DBP (primary endpoint) than candesartan cilexetil recipients (). Olmesartan medoxomil had an early onset of action; after 1 and 2 weeks of treatment, the mean decreases in daytime DBP were 72% and 90% of those observed at 8 weeks, compared with 68% and 78% with candesartan cilexetil. Olmesartan medoxomil also reduced mean ambulatory 24 h DBP and daytime SBP by significantly more than candesartan cilexetil (). It should be noted that the dose selection in this comparison reflected the current recommended maintenance doses according to product information, at the time of study development, as required by regulatory authorities for head-to-head trials.

A smaller open-label trial has compared the effects of once-daily olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg with valsartan 160 mg in 114 patients using ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) with DBP >95 mmHg and <110 mmHg (CitationDestro et al 2005) After 8 weeks of treatment, both olmesartan medoxomil and valsartan significantly reduced mean ambulatory 24 h DBP (by 11.2 mmHg and 12.2 mmHg, respectively) and SBP (14.6 mmHg and 15.7 mmHg, respectively), daytime DBP (11.8 mmHg and 12.7 mmHg, respectively) and SBP (15.0 mmHg and 16.0 mmHg, respectively), and nighttime DBP (9.7 mmHg and 10.8 mmHg) and SBP (13.7 mmHg and 14.5 mmHg) from baseline (p<0.001). It should be noted that these results were achieved with a relatively high dose of valsartan. In Europe, the recommended dose is 80 mg, with higher doses recommended for patients who require further BP lowering.

Versus a calcium channel blocker

In two multicenter, randomized, parallel-group trials with placebo run-in periods, olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg was compared with the calcium channel blockers amlodipine 5 mg (CitationChrysant et al 2003) and felodipine 5 mg (CitationStumpe and Ludwig 2002) in patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension.

When the trial comparing olmesartan medoxomil with amlodipine was published (CitationChrysant et al 2003), amlodipine was the most widely prescribed antihypertensive agent for patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension. In this trial, 440 patients were randomized 3:3:1 to one of the active treatments or placebo. After treatment for 8 weeks, olmesartan medoxomil and amlodipine both reduced mean 24 h ambulatory DBP (primary endpoint) and SBP from baseline by significantly (p<0.001) more than placebo (DBP 7.7 mmHg and 7.0 mmHg vs 1.4 mmHg; SBP 12.2 mmHg and 12.3 mmHg vs 2.3 mmHg). Ninety percent CI comparing the mean change between olmesartan and amlodipine were −1.88, 0.47 and −1.96, 1.96, for 24 h DBP and SBP, respectively. Control rates of mean 24 h DBP <85 mmHg and SBP <130 mmHg were assessed, olmesartan medoxomil was significantly (p≤0.01) superior to both amlodipine and placebo. Using these criteria, for the olmesartan medoxomil, amlodipine and placebo groups the 24 h ambulatory control rates were 48.0%, 34.3%, and 11.1% (DBP) and 33.9%, 17.4%, and 3.7% (SBP), respectively. Absolute differences between the 90% CI Both agents were well tolerated; the overall incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events did not differ significantly among the three groups (25.8%–35.5%), and most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity and judged to be remotely or definitely not related to treatment. As would be expected from the established tolerability profile of amlodipine, the incidence of edema was higher in the amlodipine group (9.1%) than the olmesartan medoxomil (4.3%) or placebo (4.5%) groups, as was the incidence of nausea (2.7%, 0%, and 0%). It should be noted that at the time of study design development target DBP <85 mmHg was considered clinically appropriate.

In the other trial, 187 patients received olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg once daily and 194 received felodipine 5 mg once daily (CitationStumpe and Ludwig 2002). The dose of each medication could be doubled for non-responders after 4 weeks. After treatment for 12 weeks, there was no significant difference between olmesartan medoxomil and felodipine in reductions from baseline for mean sitting DBP (17.5 mmHg and 17.0 mmHg) and SBP (19.9 mmHg and 19.1 mmHg). The responder rates were 82.8% for olmesartan medoxomil and 83.3% for felodipine. Both agents were well tolerated; however, as expected, the incidence of edema was higher with felodipine (2.6%) than olmesartan (0%).

Versus an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

Olmesartan medoxomil 5 mg once daily was compared with captopril 12.5 mg twice daily in 291 patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension (mean sitting DBP 95–114 mmHg) in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial (CitationWilliams 2001; CitationStumpe and Ludwig 2002). The dose of either medication could be doubled after 4 weeks and again after 8 weeks for non-responders. After 12 weeks, olmesartan medoxomil reduced mean sitting DBP and SBP from baseline by significantly more than captopril (9.9 mmHg vs 6.8 mmHg, 95% CI 4.8, 1.5 [DBP]; 14.7 mmHg vs 7.1 mmHg, 95% CI 10.4, 4.7 [SBP]). Additionally, the response rate was significantly higher for olmesartan medoxomil recipients (53% vs 38%, p<0.01). The average final dose for olmesartan medoxomil was 10.4 mg once daily (41.7% of patients were on the 5 mg dose) and for captopril was 37.0 mg twice daily (54.9% of patients on the 50 mg dose) after 12 weeks.

Versus a beta-blocker

In a double-blind study, 326 patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension (mean sitting DBP 95–114 mmHg) were randomized to receive once-daily olmesartan medoxomil 10 mg or atenolol 50 mg for 12 weeks; after 4 weeks, the dose of either medication could be doubled for non-responders (CitationVan Mieghem 2001; CitationStumpe and Ludwig 2002). After treatment for 12 weeks, both olmesartan medoxomil and atenolol reduced mean sitting DBP from baseline by a similar amount (14.2 mmHg and 13.9 mmHg), whereas olmesartan medoxomil reduced mean sitting SBP by significantly more than atenolol (21.2 mmHg vs 17.1 mmHg, 95% CI 6.6, 1.6).

Recent, forthcoming and ongoing studies with olmesartan medoxomil

The OLMesartan: reduction of Blood Pressure in the treatment of patients suffering from mild-to-moderate ESentTial hypertension (OlmeBEST) study is a recent multinational, parallel group, partially-randomised double-blind study which involved more than 1600 patients with hypertension from Austria, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. After a 2-week placebo run-in, patients received olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg/day open label for 8 weeks. After this, patients who did not achieve a DBP of <90 mmHg were randomised to 4 weeks of treatment with olmesartan medoxomil 40 mg/day or olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg/day plus hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg/day. Interim results from Germany (n=823) for the open label phase showed that DBP and SBP had been reduced by 11.8 mmHg and 17.1 mmHg, respectively (CitationEwald et al 2005).

Renin–angiotensin blockade

It has been shown that certain angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), including losartan and valsartan, do not produce complete 24 h receptor blockade at their recommended doses (CitationMaillard et al 2002). Combining an ACE inhibitor with an ARB could be used to prolong and increase RAS blockade. However, such an approach would of course expose patients to the risk of ACE inhibitor-associated side effects such as cough.

A recent double-blind cross-over study in healthy normotensive males investigated the effects of RAS blockade with the olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg, 40 mg and 80 mg, and compared this with the ACE inhibitor lisinopril 20 mg alone, or combined with olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg or 40 mg. The primary end-point was the degree of RAS blockade as assessed by SBP response to intravenously administered angiotensin I. At trough, the SBP response was 58% to either lisinopril 20 mg or olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg, 76% to olmesartan 80 mg and 80% to olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg plus lisinopril 20 mg. Thus, the 80 mg dose of olmesartan medoxomil was as effective as a lower dose combined with an ACE inhibitor (CitationHasler et al 2005). This shows that using a higher dose of olmesartan medoxomil can produce an almost complete 24 h RAS blockade. Such a treatment strategy is preferable since it would of course be free from the side effect concerns associated with the use of an ACE inhibitor.

General practice

Patients with hypertension usually respond well to appropriate intervention in the setting of controlled clinical trials. However, the situation in general practice is less certain and issues such as compliance and the lower frequency of patient–physician meetings have the potential to reduce the efficacy of treatment. In this context, two studies have assessed the efficacy and tolerability of olmesartan medoxomil in patients with hypertension in a general practice situation.

The OlmePAS study enrolled more than 12 000 patients in Germany. Physicians in more than 3400 clinical practices were involved in the study. The initial results indicate that olmesartan 20 mg was the most frequently prescribed dose and that after 12 weeks of treatment the mean decrease from baseline was 28.4 mmHg SBP and 14.2 mmHg for DBP (CitationScholze and Ewald 2005). The OlmeTEL study (Olmetec zur Behandlung von Patienten mit essentialler Hypertonie. Telemonitoring Blutdruck) (n=53) assessed the feasibility of using BP self-monitoring (BPSM) to monitor treatment with olmesartan medoxomil in a study carried out in 27 clinical practices in Germany. The median dose of olmesartan medoxomil was 20 mg, and after 12 weeks, decreases from baseline of 27.6 mmHg and 16.0 mmHg were seen in office SBP and DBP, respectively (CitationMengden et al 2004). Thus, in a general practice setting, olmesartan medoxomil produces BP reductions that are of a similar magnitude to those seen in controlled clinical studies.

24 hour blood pressure control

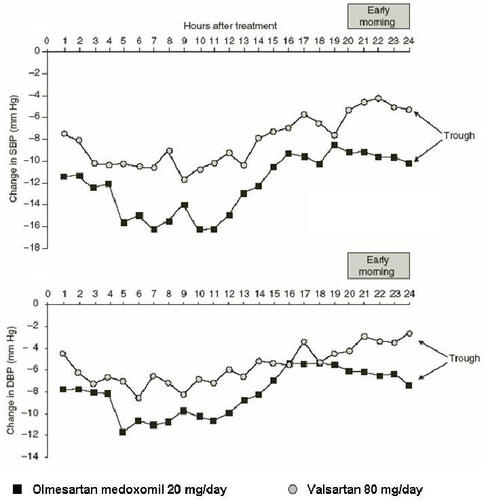

BP shows a natural diurnal variation in both normotensive and hypertensive individuals (CitationMuller et al 1985). During the early morning there is a ‘surge’ in BP which has been shown to coincide with an increase in the rate of cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death (CitationCohen et al 1997). Blood pressure measurement using ABPM enables the efficacy of antihypertensive treatments to be assessed throughout the whole of a 24 h dosing period. This method of assessing antihypertensive efficacy was used in the comparative studies by CitationOparil and colleagues (2001) and CitationBrunner and colleagues (2003). A recent post-hoc analysis of the results reported by CitationOparil and colleages (2001) showed that the mean reductions from baseline after 8 weeks with olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg were greater than those with valsartan 80 mg for SBP and DBP for all dosing periods analysed (). These periods included the whole of the 24 h dosing period, daytime and night-time periods and the last 4 h and 2 h of ABPM, which is the time associated with the early morning ‘surge’ in BP. The reductions from baseline with olmesartan medoxomil were also greater than those seen with losartan 50 mg for SBP for all dosing periods analysed and were numerically greater than those produced by irbesartan 150 mg (CitationSmith et al 2005). A similar post-hoc analysis of the study reported by Brunner et al. also showed that olmesartan medoxomil provided BP control over 24 h in terms of the proportions of patients achieving ABPM goals and larger decreases from baseline during the last 4 h and 2 h of ABPM (CitationBrunner and Arakawa 2005).

Figure 2 Hourly mean change in SBP and DBP by ABPM from baseline to the end of 8 weeks of treatment with olmesartan medoxomil 20 mg/day or valsartan 80 mg/day, with the early morning period indicated (CitationSmith et al 2005).

Target organ protection

Type 2 diabetes is strongly associated with hypertension and kidney damage. The first clinically detectable sign of renal disease is microalbuminuria which is a predictor for nephropathy as well as cardiovascular disease (CitationMogensen 2002). Studies have shown that angiotensin II receptor antagonists have renoprotective effects in diabetes (CitationBrenner et al 2001; CitationLewis et al 2001) and can slow the progression of microalbuminuria (CitationParving et al 2001). However, what is not known is whether the development of microalbuminuria can be prevented or slowed by an angiotensin II receptor antagonist.

The Randomised Olmesartan And Diabetes MicroAlbuminuria Prevention (ROADMAP) study is the first large-scale, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind primary prevention trial which specifically aims to determine whether olmesartan medoxomil 40mg daily can prevent or delay the onset of microalbuminuria in normoalbuminuric patients with type 2 diabetes (with or without hypertension) who are at risk of developing microalbuminuria due to the presence of one or more cardiovascular risk factors (CitationHaller et al 2006).

The primary endpoint of this multicenter, multinational study is the occurrence of microalbuminuria. Patient recruitment started in 2004 and the clinical phase will last until 325 events of microalbuminuria have occurred, which is expected to require a median duration of treatment of 5 years. Secondary endpoints include the occurrence of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events. ROADMAP is an important study because it has been designed to have sufficient power to assess whether changes in the onset of microalbuminuria will translate into reductions in the risk of cardiovascular and renal disease. The results of this landmark study are expected to be available around 2012, and may contribute to the development of new approaches to the management of patients with diabetes.

Atherosclerotic vascular disease is a major contributor to myocardial and cerebral infarction and hypertension is a major risk factor for the development and progression of atherosclerosis. Studies mentioned earlier, such as those in animals and in markers of vascular inflammation (the EUTOPIA study) indicate that agents that inhibit the RAS such as olmesartan medoxomil may possess antiatherosclerotic efficacy. This is being investigated in Multi-centre Olmesartan Atherosclerosis Regression Evaluation (MORE) study. This multinational, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study compares the effects of olmesartan medoxomil with those of atenolol on atherosclerosis in middle-aged to older hypertensive patients with increased cardiovascular risk. The MORE study will assess changes from baseline to various timepoints (including 28, 52, and 104 weeks) in carotid artery intimamedia thickness and plaque volume measured by 3D ultrasonography. It is hoped that initial results from the MORE study will be presented in 2006.

Tolerability

As outlined in earlier sections of this review, olmesartan medoxomil has a consistently excellent tolerability profile. In a pooled analysis of seven trials, olmesartan medoxomil (2.5–80 mg/day) had a similar tolerability profile to placebo (), and there were no apparent dose-related trends (CitationNeutel 2001).

Figure 3 Adverse events reported by >1% of patients with hypertension in a meta-analysis of seven randomized clinical trials (CitationNeutel 2001) in which patients with hypertension randomly were randomized to olmesartan medoxomil (various doses from 2.5mg/day to 80mg/day; n=2540) or placebo (n=555) for 6 to 12 weeks. Copyright © 2002. Reproduced with permission from Warner GT, Jarvis B. 2002. Olmesartan medoxomil. Drugs, 62:1345-53; discussion, 1354-6.

Direct comparison trials have shown that the tolerability of olmesartan medoxomil was comparable with that of the other angiotensin II receptor antagonists with which it was compared (CitationOparil et al 2001; CitationBrunner et al 2003). Adverse events that were at least possibly related to treatment were experienced by 8.2%, 9.3%, 9.0%, and 7.5% of olmesartan medoxomil, losartan, valsartan, and irbesartan recipients, respectively, in one of the double-blind trials (CitationOparil et al 2001; CitationWilliams 2001) and 4.1% and 6.5% of olmesartan medoxomil and candesartan cilexetil recipients in the other double-blind trial (CitationBrunner et al 2003). In both trials, there were no serious treatment-related adverse events. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection (2.7% of olmesartan medoxomil and losartan recipients, 8.3% of valsartan and 5.5% of irbesartan recipients) headache (4.0%–5.5%), fatigue (1.4%–3.3%), back pain (0.7%–3.3%), dizziness (0.7%–3.4%), and diarrhea (0.7%–3.4%) in one trial (CitationOparil et al 2001), and headache (1.3% and 2.5% of olmesartan medoxomil and candesartan cilexetil recipients), increased γ-glutamyl transferase (1.6% and 1.2%), and hypertriglyceridemia (0.6% and 1.9%) in the other trial (CitationBrunner et al 2003).

When compared with calcium channel blockers, the frequencies of adverse events were similar for all active treatments, except that recipients of amlodipine and felodipine had a higher incidence of edema than olmesartan medoxomil recipients (CitationStumpe and Ludwig 2002; CitationChrysant et al 2003).

Like other angiotensin II receptor antagonists, olmesartan medoxomil does not appear to be associated with adverse events such as cough and angioedema, which are often observed with ACE inhibitors.

Cost effectiveness

A pharmacoeconomic analysis, using efficacy data from the trial that compared olmesartan medoxomil with losartan, valsartan, and irbesartan (CitationOparil et al 2001), has been performed from the perspective of the managed healthcare environment in the US (CitationSimons 2003). Only direct medical expenditures associated with cardiovascular events were taken into account; these included acute hospitalization, emergency room visits, doctor visits, outpatient services, and prescription medicines. Data from the Framingham Heart study were used to quantify the reductions in the risk for cardiovascular events, and a managed care database was used to obtain US costs for treating the consequences of inadequate control of hypertension. Based on incremental benefits calculated using Framingham models and the absolute reductions in DBP at 8 weeks from the clinical trial, treating patients in the studied setting with olmesartan medoxomil instead of the other three angiotensin II receptor antagonists may decrease the overall cost of medical care for patients with uncontrolled hypertension ().

Table 3 Cost effectiveness estimates of olmesartan medoxomil versus other angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Estimates are based on treatment for 5 years in a hypothetical cohort of 100 000 individuals. Incremental benefits (events avoided) were calculated using Framingham models and the absolute reductions in diastolic blood pressure at 8 weeks in a clinical trial comparing the four agents (CitationSimons 2003)

The results indicated that substantial cost savings were possible with olmesartan medoxomil. For example, when compared with valsartan, olmesartan medoxomil reduced estimated costs over 5 years in a hypothetical cohort of 100 000 patients by $16 231 000 for cardiovascular disease and $11 955 000 for coronary heart disease. The estimated reduction in costs with olmesartan medoxomil over 5 years when compared with losartan was estimated to be $15 149 000 for cardiovascular disease and $11 107 000 for coronary heart disease. At the time of the analysis, no price had been set for olmesartan medoxomil so it was assumed that the angiotensin II receptor blockers were all the same price. Olmesartan medoxomil has since been priced lower than other angiotensin II receptor antagonists in the USA; therefore the results from this analysis were probably underestimated.

Discussion

It is now apparent that intensive control of BP reduces the mortality and morbidity associated with hypertension, and clear BP goals have been set to guide physicians in their management of patients with hypertension (CitationChobanian et al 2003; CitationESH–ESC 2003) Although combination therapy will be required by many high-risk patients to reach BP targets, the initial use of an effective and well tolerated agent should improve patient compliance and reduce the number of steps needed to reach BP control.

Olmesartan medoxomil is a selective angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist with proven BP-lowering efficacy. In a number of clinical trials, the agent generally lowered both mean DBP and SBP by at least 10 mmHg after treatment for 8 weeks. Importantly, the majority of patients in clinical trials achieved target DBP of <90 mmHg (CitationNeutel 2001; CitationPuchler et al 2001; CitationChrysant et al 2003) Olmesartan medoxomil has a rapid onset of action, with significant improvements in efficacy compared with placebo observed from 2 weeks onwards. The drug is also well tolerated, with an adverse event profile similar to that of placebo.

A considerable body of data now exists that demonstrates the BP-lowering efficacy of olmesartan medoxomil. At doses recommended in the EU, olmesartan medoxomil has been shown to be significantly more effective, in terms of primary endpoints of sitting cuff or ambulatory daytime DBP, than other angiotensin II receptor antagonists (valsartan, losartan, irbesartan (CitationOparil et al 2001; CitationStumpe 2004), and candesartan cilexetil (CitationBrunner et al 2003) at their respective, recommended doses. The greater BP reduction seen with olmesartan may have long term clinical implications since even small decreases in BP have been associated with changes in the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Moreover, because of this improved efficacy, cost estimates indicate that olmesartan medoxomil may be more cost effective than valsartan, losartan, and irbesartan (CitationSimons 2003). Additionally, olmesartan medoxomil has been shown to be at least as effective as the calcium channel blockers amlodipine (CitationChrysant et al 2003) and felodipine (CitationStumpe and Ludwig 2002) and the beta-blocker atenolol (CitationVan Mieghem 2001), and significantly more effective than the ACE inhibitor captopril at the doses tested (CitationWilliams 2001).

Current treatment guidelines emphasize the need to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertension. Patients with hypertension frequently suffer from other conditions that increase their cardiovascular risk, such as atherosclerosis. Studies such as the MORE study are helping to further define the potential benefits of olmesartan medoxomil in the overall reduction of cardiovascular risk by investigating its effects in patients with atherosclerosis. Patients with type 2 diabetes are also at increased risk of cardiovascular disease and olmesartan medoxomil may come to play a major role in treating such patients. Treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes with olmesartan medoxomil has been shown to reduce renal vascular resistance and oxidative stress, and increase renal perfusion in addition to significantly reducing BP (CitationFliser et al 2005). Such effects may translate into beneficial long-term renoprotective effects and this is being investigated in the 5 year ROADMAP study, which commenced in 2004. This study will assess whether olmesartan medoxomil can prevent or delay the onset of microalbuminuria, and whether this translates into protection against cardiovascular events and renal disease, in patients with type 2 diabetes. Studies such as MORE and ROADMAP should help to establish that olmesartan medoxomil offers benefits in terms of cardiovascular risk reduction that go beyond BP reduction.

As well as having a good tolerability profile, olmesartan medoxomil has a low potential for drug interactions, and a pharmacokinetic profile that allows it to be administered once daily. Recent studies show that olmesartan medoxomil produces almost complete 24 h blockade of the RAS. These factors will make the agent easy to prescribe, and should aid patient treatment compliance.

In conclusion, olmesartan medoxomil is an effective, fast-acting, and well tolerated antihypertensive agent that can be administered once daily. At recommended doses, it is significantly more effective at reducing BP than several other agents of its class. Thus, olmesartan medoxomil represents a good option for the initial intensive treatment of patients with hypertension.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Phil Jones of Adis Communications for editorial support provided during the preparation of this review.

References

- BrennerBMCooper medeZeeuwDEffects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathyN Engl J Med2001345861911565518

- BrunnerHArakawaKAntihypertensive efficacy of olmesartan medoxomil and candesartan cilexetil in achieving 24-hour blood pressure reductions and ambulatory blood pressure goalsClin Drug Invest2005in press

- BrunnerHRExperimental and clinical evidence that angiotensin II is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseaseAm J Cardiol2001873C9C

- BrunnerHRThe new oral angiotensin II antagonist olmesartan medoxomil: a concise overviewJ Hum Hypertens200216Suppl 2S131611967728

- BrunnerHRClinical efficacy and tolerability of olmesartanClin Ther200426Suppl AA283215291377

- BrunnerHRNussbergerJWaeberBControl of vascular tone by renin and angiotensin in cardiovascular diseaseEur Heart J199314Suppl I149538293766

- BrunnerHRStumpeKOJanuszewiczAAntihypertensive efficacy of olmesartan medoxomil and candesartan cilexetil assessed by 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in patients with essential hypertensionClin Drug Invest20032341930

- BurnierMBrunnerHRAngiotensin II receptor antagonistsLancet20003556374510696996

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRThe Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 reportJAMA200328925607212748199

- ChrysantSGMarburyTCRobinsonTDAntihypertensive efficacy and safety of olmesartan medoxomil compared with amlodipine for mild-to-moderate hypertensionJ Hum Hypertens2003174253212764406

- CohenMCRohtlaKMLaveryCEMeta-analysis of the morning excess of acute myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac deathAm J Cardiol1997791512169185643

- ConlinPRGerthWCFoxJFour-year persistence patterns among patients initiating therapy with the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan versus other artihypertensive drug classesClin Ther2001231999201011813934

- DestroMScabrosettiRVanasiaAComparative efficacy of valsartan and olmesartan in mild-to-moderate hypertension: results of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoringAdv Ther200522324315943220

- [ESH–ESC] European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology2003 European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertensionJ Hypertens200321610115312777938

- EwaldSNickenigGBöhmMOlmebest-study: reduction of blood pressure in the treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate essential hypertension - interim analysis of the German sub studyAm J Hypertens2005182

- FletcherAEPalmerAJBulpittCJCough with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors: how much of a problem?J Hypertens Suppl199412S4377965265

- FliserDBuchholzKHallerHAntiinflammatory effects of angiotensin II subtype 1 receptor blockade in hypertensive patients with microinflammationCirculation20041101103715313950

- FliserDWagnerKKLoosAChronic angiotensin II receptor blockade reduces (intra)renal vascular resistance in patients with type 2 diabetesJ Am Soc Nephrol20051611354015716329

- HallerHVibertiGMimranAPreventing microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes - rationale and design of the Randomised Olmesartan And Diabetes MicroAlbuminuria Prevention (ROADMAP) StudyJ Hypertens2006in press

- HaslerCNussbergerJMaillardMSustained 24-hour blockade of the renin-angiotensin system: a high dose of a long-acting blocker is as effective as a lower dose combined with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitorClin Pharmacol Ther2005785501716321616

- KoikeHNew pharmacologic aspects of CS-866, the newest angiotensin II receptor antagonistAm J Cardiol200187Suppl 8A33C36C

- KoikeHSadaTMizunoMIn vitro and in vivo pharmacology of olmesartan medoxomil, an angiotensin II type AT1 receptor antagonistJ Hypertens Suppl200119Suppl 1S31411451212

- LewingtonSClarkeRQizilbashNAge-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studiesLancet200236019031312493255

- LewisEJHunsickerLGClarkeWRRenoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetesN Engl J Med20013458516011565517

- MaillardMPWurznerGNussbergerJComparative angiotensin II receptor blockade in healthy volunteers: the importance of dosingClin Pharmacol Ther200271687611823759

- MazzolaiLBurnierMComparative safety and tolerability of angiotensin II receptor antagonistsDrug Saf199921233310433351

- MengdenTEwaldSKaufmannSTelemonitoring of blood pressure self measurement in the OLMETEL studyBlood Press Monit20049321515564988

- MizunoMSadaTIkedaMPharmacology of CS-866, a novel nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonistEur J Pharmacol199528518188566137

- MogensenCEDiabetic renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: new strategies for prevention and treatmentTreat Endocrinol2002131115765616

- MullerJEStonePHTuriZGCircadian variation in the frequency of onset of acute myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med19853131315222865677

- NeutelJMClinical studies of CS-866, the newest angiotensin II receptor antagonistAm J Cardiol20018737C43C

- NussbergerJKoikeHAntagonizing the angiotensin II subtype 1 receptor: a focus on olmesartan medoxomilClin Ther200426Suppl AA122015291375

- OparilSWilliamsDChrysantSGComparative efficacy of olmesartan, losartan, valsartan, and irbesartan in the control of essential hypertensionJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)200132839131811588406

- ParvingHHLehnertHBrochner-MortensenJThe effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetesN Engl J Med2001345870811565519

- PuchlerKLaiesPStumpeKOBlood pressure response, but not adverse event incidence, correlates with dose of angiotensin II antagonistJ Hypertens Suppl200119s41811451214

- PuchlerKNussbergerJLaeisPBlood pressure and endocrine effects of single doses of CS-866, a novel angiotensin II antagonist, in salt-restricted hypertensive patientsJ Hypertens19971512 Pt 21809129488244

- Sankyo Pharma GmbH2002 Data on file (integrated summary of efficacy)

- ScholzeJEwaldSOLMEPAS – STUDY: Olmesartan medoxomil for the treatment of hypertension under daily-practice conditions – results of a post-authorization study2005Berlin, GermanyDeutsche Hypertonie Ligatagung

- SchwochoLRMasonsonHNPharmacokinetics of CS-866, a new angiotensin II receptor blocker, in healthy subjectsJ Clin Pharmacol2001415152711361048

- SimonsWRComparative cost effectiveness of angiotensin II receptor blockers in a US managed care setting: olmesartan medoxomil compared with losartan, valsartan, and irbesartanPharmacoeconomics200321617412484804

- SmithDHDubielRJonesMUse of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to assess antihypertensive efficacy: a comparison of olmesartan medoxomil, losartan potassium, valsartan, and irbesartanAm J Cardiovasc Drugs20055415015631537

- StumpeKOOlmesartan compared with other angiotensin II receptor antagonists: head-to-head trialsClin Ther200426Suppl AA33715291378

- StumpeKOLudwigMAntihypertensive efficacy of olmesartan compared with other antihypertensive drugsJ Hum Hypertens200216Suppl 2S24811967729

- TakemotoMEgashiraKTomitaHChronic angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade: effects on cardiovascular remodeling in rats induced by the long-term blockade of nitric oxide synthesisHypertension199730162179403592

- TomitaHEgashiraKOharaYEarly induction of transforming growth factor-beta via angiotensin II type 1 receptors contributes to cardiac fibrosis induced by long-term blockade of nitric oxide synthesis in ratsHypertension19983227399719054

- UsuiMEgashiraKTomitaHImportant role of local angiotensin II activity mediated via type 1 receptor in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular inflammatory changes induced by chronic blockade of nitric oxide synthesis in ratsCirculation20001013051010645927

- Van MieghemWA multi-centre, double-blind, efficacy, tolerability and safety study of the oral angiotensin II-antagonist olmesartan medoxomil versus atenolol in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension [abstract]J Hypertens200119S1523

- VleemingWvan AmsterdamJGStrickerBHACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. Incidence, prevention and managementDrug Saf199818171889530537

- WarnerGTJarvisBOlmesartan medoxomilDrugs200262134553 discussion, 1354-612076183

- WehlingMCan the pharmacokinetic characteristics of olmesartan medoxomil contribute to the improvement of blood pressure control?Clin Ther200426Suppl AA21715291376

- WilliamsPAA multi-centre, double-blind, efficacy, tolerability and safety study of the oral angiotensin II-antagonist olmesartan medoxomil versus captopril in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension [abstract]J Hypertens200119suppl 2S300

- YusufSHawkenSOunpuuSEffect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control studyLancet20043649375215364185