Abstract

Blood pressure (BP) measurements provide information regarding risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease, but only in a specific artery. Arterial stiffness (AS) can be determined by measurement of arterial pulse wave velocity (APWV). Separate from any role as a surrogate marker, AS is an important determinant of pulse pressure, left ventricular function and coronary artery perfusion pressure. Proximal elastic arteries and peripheral muscular arteries respond differently to aging and to medication. Endogenous human growth hormone (hGH), secreted by the anterior pituitary, peaks during early adulthood, declining at 14% per decade. Levels of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) are at their peak during late adolescence and decline throughout adulthood, mirror imaging GH. Arterial endothelial dysfunction, an accepted cause of increased APWV in GH deficiency (GHD) is reversed by recombinant human (rh) GH therapy, favorably influencing the risk for atherogenesis. APWV is a noninvasive method for measuring atherosclerotic and hypertensive vascular changes increases with age and atherosclerosis leading to increased systolic blood pressure and increased left ventricular hypertrophy. Aerobic exercise training increases arterial compliance and reduces systolic blood pressure. Whole body arterial compliance is lowered in strength-trained individuals. Homocysteine and C-reactive protein are two inflammatory markers directly linked with arterial endothelial dysfunction. Reviews of GH in the somatopause have not been favorable and side effects of treatment have marred its use except in classical GHD. Is it possible that we should be assessing the combined effects of therapy with rhGH and rhIGF-I? Only multiple intervention studies will provide the answer.

Introduction

Arterial distensibility and arterial compliance decrease with age and atherosclerosis leading to increased systolic blood pressure (SBP) and a widening of the pulse pressure (PP), resulting in left ventricular hypertrophy, a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) (CitationLaogun and Gosling 1982; CitationRiley et al 1986).

Early changes in vascular properties precede the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and hypertensive heart disease (CitationCohn et al 1995). Arterial pulse wave velocity (APWV) and compliance alterations occur early in the course of essential hypertension in relation to other CVD risk factors (CitationBrinton et al 1996). Physical properties of the vasculature require a measurement of the distending force (ie, BP), using pressure transducers at relevant sites (CitationAsmar et al 1995). The form of the pulse wave through the walls of the blood vessels is affected by the mechanical properties of the vessels. Pulse-wave augmentation results from reflections of the pulse wave at distal sites (such as bifurcations), such that the forward wave and reflected wave superimpose producing the typical arterial pulse wave, which differs at different sites (CitationO’Rourke 1999). The PWV and the amplitude of reflected waves are increased in stiffer arteries, and are reduced with increased arterial compliance (CitationO’Rourke et al 2001). These features are dependent on a number of hemodynamic variables, including heart rate and PP (CitationWilkinson et al 2002a). Therefore, measurements of augmentation are generally corrected for PP and expressed as an “augmentation index” (AIx).

These measurements are also affected by vasoactive drugs (CitationO’Rourke 1992; CitationKelly et al 2001; CitationWilkinson et al 2001a) and by insulin (CitationWesterbacka et al 1999) and are sensitive to inhibition of nitric oxide synthase (CitationKinlay et al 2001; CitationStewart et al 2003). The application of these measurements in concert with vasodilators has been proposed as an alternative approach for the measurement of vascular function (CitationWilkinson et al 2002b).

Arterial pulse wave velocity

Measurement of arterial wave propagation as an index of vascular stiffness and vascular health dates back to the early part of the last century (CitationBramwell and Hill 1922).

The arrival of the pulse wave at two different arterial sites is timed, and from estimates of the length of blood vessels between these sites (by measuring the distances at overlying skin sites), the velocity of this wave is calculated in m.s−1 (CitationO’Rourke 1999; CitationLehmann 1999; CitationWilkinson et al 1999). Subtleties come in correctly estimating the intervening distances. This provides a reliable measure of arterial stiffness; at a given blood pressure, the stiffer the vessel, the less time it takes for the pulse wave to travel the length of the vessel. The APWV, especially of the aorta, has emerged as an important independent predictor of cardiovascular events. APWV increases with stiffness and is defined by the Moens–Korteweg equation, PWV = √(Eh/2PR), where E is Young’s modulus of the arterial wall, h is wall thickness, R is arterial radius at the end of diastole, and P is blood density (CitationLehmann 1999).

The time delay between the arrival of a predefined part of the pulse wave, such as the foot, at two points is obtained either by simultaneous measurement, or by gating to the peak of the R-wave of the ECG. The distance travelled by the pulse wave is measured over the body surface and APWV is then calculated as distance divided by time (m.s−1) and depends on anatomical variation. The abdominal aorta tends to become more tortuous with age potentially leading to an underestimation of APWV (CitationWenn and Newman 1990). APWs can also be detected by using Doppler ultrasound (CitationSutton-Tyrrell et al 2001) or applanation tonometry (CitationWilkinson et al 1998b) where the pressure within a small micromanometer flattened against an artery equates to the pressure within the artery. Increases in distending pressure increase APWV (CitationBramwell and Hill 1922). Therefore, account should be taken of the level of BP in studies that use APWV as a marker of cardiovascular risk.

An increase in HR of 40 beats per minute was shown to increase APWV by >1 m/s (CitationLantelme et al 2002). Also acute increases in heart rate (HR) markedly lower arterial distensibility, occurring in both large and middle-size muscular arteries within the range of “normal” HR values (CitationGiannattasio et al 2003). Raised APWV occurs with a range of established cardiovascular risk factors (CitationLehmann et al 1998) including age (CitationBramwell et al 1923; CitationVaitkevicius et al 1993), hypercholesterolemia (CitationLehmann et al 1992a), type II diabetes mellitus (DM) (CitationLehmann et al 1992b), and sedentary lifestyle (CitationVaitkevicius et al 1993). In hypertension, carotid-femoral APWV is an independent predictor of both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality (CitationLaurent et al 2001). The odds ratio for a 5 m.s−1 (a relatively large change in PWV) increment in PWV was 1.34 for all-cause mortality and 1.51 for cardiovascular mortality. In contrast, PP was independently related to all-cause mortality but only marginally related to cardiovascular mortality, indicating that specific assessment of arterial stiffness, with APWV, may be of greater value in the evaluation of risk. APWV ranged from 9 to 13 m.s−1, whereas recently quoted values of carotid-femoral PWV in healthy individuals with average ages of 24 to 62 years ranged from around 6 to 10 m.s−1 (CitationO’Rourke et al 2002). In hypertensive subjects without a history of overt cardiovascular disease APWV also predicts the occurrence of cardiovascular events independently of classic risk factors (CitationBoutouyrie et al 2002). Aortic APWV >13 m.s−1 is a particularly strong predictor of cardiovascular mortality in hypertension (CitationBlacher et al 1999a). Carotid-femoral APWV significantly increases at a faster rate in treated hypertensives than in normotensive controls, although where BP was well controlled APWV progression was attenuated (CitationBenetos et al 2002).

Aortic APWV, assessed by using Doppler flow recordings, independently predicts mortality in patients with end-stage renal failure (ESRF), a population with a particularly high rate of cardiovascular disease (CitationBlacher et al 1999b; CitationSafar et al 2002). The benefit associated with BP control in ESRF, by the use of anti-hypertensives, was independently related to change in aortic APWV, such that a reduction in APWV of 1 m.s−1 was associated with a relative risk of 0.71 for all-cause mortality (CitationGuerin et al 2001).

The mechanisms of arterial stiffness

Windkessel theory treats the circulation as a central elastic reservoir (the large arteries), into which the heart pumps, and from which blood travels to the tissues through relatively nonelastic conduits (CitationOliver and Webb 2003). The elasticity of the proximal large arteries is the result of the high elastin to collagen ratio in their walls, which progressively declines toward the periphery. The increase in arterial stiffness that occurs with age (CitationHallock and Benson 1937) is the result of progressive elastic fibre degeneration (CitationAvolio et al 1998). The aorta and its major branches are large arteries, which can be differentiated from the more muscular conduit arteries, such as the brachial and radial arteries. The elasticity of a given arterial segment is not constant but instead depends on its distending pressure (CitationHallock and Benson 1937; CitationGreenfield and Patel 1962). As distending pressure increases, there is greater recruitment of relatively inelastic collagen fibres and, consequently, a reduction in elasticity (CitationBank et al 1996). In addition to collagen and elastin, the endothelium (CitationWilkinson et al 2002a) and arterial wall smooth muscle bulk and tone (CitationBank et al 1999) also influence elasticity. A number of genetic influences on arterial stiffness have also been identified. Polymorphic variation in the fibrillin-1 receptor (CitationMedley et al 2002), angiotensin II type-1 receptor and endothelin receptor (CitationLajemi et al 2001a) genes are related to stiffness. The angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) I/D polymorphism has been associated with stiffness (CitationBalkestein et al 2001), but not consistently (CitationLajemi et al 2001b). As a consequence of differing elastic qualities and wave reflection, the shape of the arterial waveform varies throughout the arterial tree. In healthy, relatively young subjects, whereas mean arterial pressure (MAP) declines in the peripheral circulation, SBP and PP are amplified (CitationKroeker and Wood 1955). This amplification is exaggerated during exercise (CitationRowell et al 1968) but reduces with increasing age (CitationWilkinson et al 2001). APWV in the brachial artery has been shown to increase with age, indicative of worsening arterial compliance (CitationAvolio et al 1983). However, brachial artery PWV (baPWV) has been reported to change less with age than APWV in the aorta or lower limb arteries. In contrast, the assessment of distensibility using APWV is indirect and potentially affected by changes in blood flow and MAP that reflect changes in more distal resistance vessels (CitationNichols and O’Rourke 1998). Atherosclerosis, hypertension, and diabetes produce macro- and micro-vascular changes that are reflected in vascular function and physical properties before the development of overt clinical disease (CitationBerenson et al 1992). Endothelial cells continuously release nitric oxide (NO), which is synthesized by the endothelial isoform of NO synthase (NOS-III) (CitationMoncada et al 1991; CitationFörstermann et al 1993). NOS-III activity is stimulated by chemical agonists such as serotonin, acetylcholine (ACh) and bradykinin (CitationFurchgott 1984; CitationCocks et al 1985; CitationNewby and Henderson 1990) and by flow-induced shear forces on the endothelial cell wall (CitationPohl et al 1986; CitationBusse and Pohl 1993; CitationMeredith et al 1996). Endothelium-derived NO diffuses toward the underlying vascular smooth muscle, producing relaxation. The vascular endothelium, therefore, plays a central role in the modulation of arterial smooth muscle tone and thus influences large-artery distensibility and the mechanical performance of the cardiovascular system (CitationRamsey et al 1995). By improving arterial elasticity, endothelium-derived NO reduces the arterial wave reflection and reduces left ventricular work and the pulse pressure within the aorta. In addition, exogenous acetylcholine and glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) both increase arterial distensibility, the former mainly through NO production. This may help explain why conditions that exhibit endothelial dysfunction are also associated with increased arterial stiffness. Therefore, reversal of endothelial dysfunction or drugs that are large-artery vasorelaxants may be effective in reducing large-artery stiffness in humans, and thus cardiovascular risk. GTN reduces brachial artery stiffness and decreases wave reflection (CitationYaginuma et al 1986). Moreover, drugs that stimulate endothelial NO release, such as ACh, also reduce muscular artery stiffness in vivo (CitationRamsey et al 1995; CitationJoannides et al 1997).

Specific studies in exercise

Changes in APWV in dynamic exercise in normal individuals, may provide a reference point against which to compare the effect of disease states and the basis for evaluation of their component mechanisms (CitationNaka et al 2003). Aerobic exercise training increases arterial compliance and reduces SBP and in cross-sectional studies, aerobically trained athletes have a higher arterial compliance than sedentary individuals (CitationMohiaddin et al 1989; CitationKingwell et al 1995; CitationVaitkevicius et al 1993). Hammer throwers recorded significantly higher compliance in the radial artery of the dominant arm relative to both the contra-lateral arm and to an inactive control group (CitationGiannattasio et al 1992). This could be explained by the dynamic nature of the action.

A single bout of cycling exercise increased whole body arterial compliance by mechanisms suggesting vasodilation. In exercising muscles, factors including local increases in temperature, carbon dioxide, acidity, adenosine, NO and magnesium and potassium ions may all contribute to local vasodilation (CitationKingwell et al 1997a). Four weeks of cycle training, in sedentary individuals, significantly increased forearm blood flow and blood viscosity, suggesting an increased basal production of nitric oxide from the forearm. The elevated shear stress in this vascular bed may contribute to endothelial adaptation (CitationKingwell et al 1997b). Both the proximal aorta and the leg arteries were significantly stiffer and contributed to significantly higher aortic characteristic impedance in strength-trained athletes (CitationBertovic et al 1999). However, large-artery stiffening associated with isolated systolic hypertension (ISH) is resistant to modification through short-term aerobic training (CitationFerrier et al 2001). In subjects 70 to 100 years old, aortic APWV was a strong, independent significant predictor of cardiovascular death, whereas systolic blood pressure or pulse pressure was not (CitationMeaume et al 2001). GTN, an exogenous NO donor significantly increased brachial artery area and compliance and significantly decreased pulse wave velocity (CitationKinlay et al 2001). In contrast to the beneficial effect of regular aerobic exercise, resistance training does not exert beneficial influences on arterial wall buffering functions (CitationMiyachi et al 2003). However, several months of resistance training “reduced” central arterial compliance in healthy men (CitationMiyachi et al 2004). The 3-hydroxyl-3-methyl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins), significantly reduced total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride levels and increased high density lipoprotein cholesterol and significantly lowered APWV (CitationFerrier et al 2002). Atorvastatin significantly reduced arterial stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, possibly through an anti-inflammatory action (CitationVan Doornum et al 2004). Age, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), triglycerides, blood glucose and uric acid were shown to be significant variables for baPWV in both genders (CitationTomiyama et al 2003). Central aortic stiffness would appear to be the initial main site for promotion of the development of coronary atherosclerosis and ischemic heart disease (CitationMcLeod et al 2004).

Physiology of growth hormone (GH)

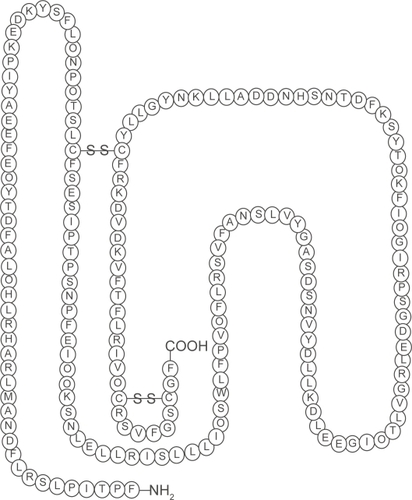

The ability of the somatotroph cells in the anterior pituitary to synthesize and secrete the polypeptide, human growth hormone (hGH) are determined by a gene called the Prophet of Pit-1 (PROP1). When GH is translated, 70%–80% is secreted as a 191-amino-acid, 4-helix bundle protein and 20%–30% as a less abundant 176-amino-acid form (CitationBaumann 1991) (). Hypothalamic-releasing and hypothalamic-inhibiting hormones acting via the hypophysial portal system control the secretion of GH, which is secreted into the circulation (CitationMelmed 2006).

Figure 1 The structure of human growth hormone. Human growth hormone in its correct 22-kD-hGH form. Three-dimensional structure, generated from the protein data base SWISS PROT. Structural data supplied with the help of the program RasMol. The n-terminal amino acid is at the bottom right hand corner. The disulphide bridges make the molecule a 3 dimensional structure (the sequence range is missing on the 20 kDa hGH variant).

In healthy persons, the GH level is usually <0.2 μg.L−1 throughout most of the day. There are approximately 10–12 intermittent bursts in a 24-hour period, mostly at night, when the level can rise to 30 μg.L−1 (CitationMelmed 2006). GH secretion declines at 14% per decade from the age of 20 years (CitationIranmanesh et al 1991).

GH action is mediated by a GH receptor, which is expressed mainly in the liver and is composed of dimers that change conformation when occupied by a GH ligand (CitationBrown et al 2005).

Cleavage of the GH receptor provides a circulating GH binding protein (GHBP), prolonging the half-life and mediating the transport of GH. Growth hormone activates the growth hormone receptor, to which the intracellular Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) tyrosine kinase binds. Both the receptor and JAK2 protein are phosphorylated, and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) proteins bind to this complex. STAT proteins are then phosphorylated and translocated to the nucleus, which initiates transcription of growth hormone target proteins (CitationArgetsinger et al 1993).

Intracellular GH signalling is suppressed by suppressors of cytokine signalling. GH induces the synthesis of peripheral insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) (CitationLe Roith et al 2001) and endocrine, autocrine and paracrine IGF-I induces cell proliferation and is thought to inhibit apoptosis (CitationO’Reilly et al 2006).

IGF-binding proteins (IGFBP) and their proteases regulate the access of ligands to the IGF-I receptor affecting its action. Levels of IGF-I are at their peak during late adolescence and decline throughout adulthood, mirror imaging GH and are determined by sex and genetic factors (CitationMilani et al 2004). IGF-I levels reflect the secretory activity of growth hormone and is a marker for identification of GH-deficiency (GHD), or excess (CitationMauras and Haymond 2005). The production of IGF-I is suppressed in malnourished patients, as well as in certain disease states, such as liver disease, hypothyroidism, or poorly controlled diabetes.

In conjunction with GH, IGF-I has varying differential effects on protein, glucose, lipid and calcium metabolism and therefore body composition (CitationMauras et al 2000). Direct effects result from the interaction of GH with its specific receptors on target cells. In the adipocyte, GH stimulates the cell to break down triglyceride and suppresses its ability to uptake and accumulate circulating lipids. Indirect effects are mediated primarily by IGF-I.

Little is known about the expression of skeletal muscle-specific isoforms of IGF-I gene in response to exercise in humans, nor the influence of age and physical training status. A single bout of isometric exercise stimulated the expression of mRNA for the IGF-I splice variants IGF-IEa and IGF-IEc (mechano growth factor [MGF]) within 2.5 hours, which lasts for at least 2 days after exercise (CitationGreig et al 2006).

Gh deficiency (GHD)

The therapeutic indications for recombinant human growth hormone (rhGH) in the UK are controlled by the CitationNational Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines (NICE 2003), which has very strict guidelines and has recommended treatment with rhGH for children with:

Growth disturbance in short children born small for gestational age

Proven GH deficiency

Gonadal dysgenesis (Turner’s syndrome)

Prader–Willi syndrome

Chronic renal insufficiency before puberty (renal function decreased to less than 50%).

Treatment should be initiated and monitored by a pediatrician with expertise in managing GH disorders; treatment can be continued under a shared-care protocol by a general practitioner. Treatment should be discontinued if the response is poor (ie, an increase in growth velocity of less than 50% from baseline) in the first year of therapy. In children with chronic renal insufficiency, treatment should be stopped after renal transplantation and not restarted for at least a year. CitationNICE (2003) has recommended rhGH in adults only if the following three criteria are fulfilled:

Severe GH deficiency, established by an appropriate method

Impaired quality of life, measured by means of a specific questionnaire

Already receiving treatment for another pituitary hormone deficiency.

Treatment should be discontinued if the quality of life has not improved sufficiently by nine months. Severe GHD developing after linear growth is complete but before the age of 25 years should be treated with rhGH; treatment should continue until adult peak bone mass has been achieved. Treatment for adult-onset GH (A-OGH) deficiency should be stopped only when the patient and the patient’s physician consider it appropriate. Treatment with somatropin should be initiated and managed by a physician with expertise in GH disorders; maintenance treatment can be prescribed in the community under a shared-care protocol (CitationBritish National Formulary 2008). A-OGH deficient individuals are overweight, with reduced lean body mass (LBM) (CitationSalomon et al 1989; CitationAmato et al 1993; CitationBeshyah et al 1995) and increased fat mass (FM), especially abdominal adiposity (CitationSalomon et al 1989; CitationBengtsson et al 1993; CitationAmato et al 1993; CitationBeshyah et al 1995; CitationSnel et al 1995). They have reduced total body water (CitationBlack et al 1972) and reduced bone mass (CitationKaufman et al 1992; CitationO’Halloran et al 1993; CitationHolmes et al 1994). There is also reduced strength and exercise capacity (CitationCuneo et al 1990, Citation1991a, Citation1991b) and reduced cardiac performance and an altered substrate metabolism (CitationBinnerts et al 1992; CitationFowelin et al 1993; CitationRussell-Jones et al 1993; CitationO’Neal et al 1994; CitationHew et al 1996). This leads to an abnormal lipid profile (CitationCuneo et al 1993; CitationRosen et al 1993; CitationDe Boer et al 1994; CitationAttanasio et al 1997) which can predispose to the development of cardiovascular disease. A-OGH deficiency reduces psychological well-being and quality of life (QoL) (CitationStabler et al 1992; CitationRosen et al 1994). The use of rhGH is currently being used successfully to treat this deficiency.

GH excess (acromegaly)

GH excess results in the clinical condition known as acromegaly. This condition is presented as a consequence of a pituitary tumor characterized by a multitude of signs and symptoms. Pituitary tumors account for approximately 15% of primary intracranial tumors (CitationMelmed 2006). Acromegalics have an increased risk of DM, hypertension and premature mortality due to CVD (CitationBengtsson et al 1993).

The most common side effects following administration arise from sodium and water retention.

Weight gain, dependent edema, a sensation of tightness in the hands and feet, or carpal tunnel syndrome; can frequently occur within days (CitationHoffman et al 1996).

Arthralgia (joint pain), involving small or large joints can occur, but there is usually no evidence of effusion, inflammation, or X-ray changes (CitationSalomon et al 1989). Muscle pains can also occur. GH administration is documented to result in hyperinsulinemia (CitationHussain et al 1993) which may increase the risk of cardiovascular complications. GH-induced hypertension (CitationSalomon et al 1989) and atrial fibrillation (CitationBengtsson et al 1993) have both been reported, but are rare. There have also been reports of cerebral side effects, such as encephalocele (CitationSalomon et al 1989) and headache with tinnitus (CitationBengtsson et al 1993) and benign intra-cranial hypertension (CitationMalozowski et al 1993).

Cessation of GH therapy is associated with regression of side effects in most cases (CitationMalozowski et al 1993).

APWV in pathological GH states

The potential mechanisms accounting for this abnormality may result from a direct IGF-I mediated effect via increased production of NO. Qualitative alterations in lipoproteins have been described in GHD adults (CitationO’Neal et al 1996), resulting in the generation of an atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype, which would contribute to endothelial dysfunction.

Growth hormone deficiency (GHD)

Increased oxidative stress exists in GHD adults, which may be a factor in atherogenesis and reduced by GH therapy’s effects on oxidative stress (CitationEvans et al 2000). Endothelial dysfunction exists in GHD adults (CitationEvans et al 1999), which is reversible with GH replacement (CitationPfeifer et al 1999). An impaired endothelial-dependent dilatation (EDD) response was documented in GHD adults, which significantly improved after GH treatment.

Patients with GHD, with increased risk of vascular disease, have impaired endothelial function and increased AIx compared with controls. Replacement of GH resulted in improvement of both endothelial function and AIx, without changing BP (CitationSmith et al 2002).

Replacement of GH for 3 months corrected endothelial dysfunction in patents with chronic heart failure (CitationNapoli et al 2002).

Renal failure induces GH resistance at the receptor and post-receptor level, with concomitant endothelial dysfunction, which can be overcome by replacement of GH (CitationLilien et al 2004).

Growth hormone excess

Acromegaly is associated with changes in the central arterial pressure waveform, suggesting large artery stiffening. This may have important implications for cardiac morphology and performance as well as increasing the susceptibility to atheromatous disease.

Large artery stiffness is reduced in “cured” acromegaly (GH < 2.5 mU.L−1) and partially reversed after pharmacological treatment of active disease (CitationSmith et al 2003).

GH and inflammatory markers of CVD

Human peripheral blood T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and monocytes express IGF-I receptors (CitationWit et al 1993). Administration of either GH or IGF-I can reverse the immunodeficiency of Snell dwarf mice (CitationVan Buul-Offers et al 1986). GH replacement induced a significant overall increase in the percent specific lysis of K562 tumor target cells, in healthy adults (CitationCrist and Kraner 1990). NK activity was significantly increased throughout the six weeks period of administration. In vitro studies, using human lymphocytes indicate that GH is important for the development of the immune system (CitationWit et al 1993). However, pre-operative administration of GH did not alter C-reactive protein (CRP), serum amyloid A (SAA) or interleukin-6 (IL-6, an inflammatory cytokine) release (CitationMealy et al 1998). Homocysteine (HCY) concentration has been established as an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis (CitationEichinger et al 1998; CitationStehouwer and Jakobs 1998). CRP and IL-6 levels and central fat decreased significantly in rhGH recipients in GHD after 18 months. Lipoprotein(a) and glucose levels significantly increased, without affecting lipid levels (CitationSesmilo et al 2000). HCY impairs vascular endothelial function through significant reduction of NO production. This appears to potentiate oxidative stress and atherogenic development (Citationvan Guldener and Stehouwer 2000). HCY levels were not significantly elevated in GHD adults and HCY was considered to be unlikely to be a major risk factor for vascular disease, if there are no other risk factors present (CitationAbdu et al 2001). Pegvisomant (GH receptor antagonist) did not induce significant acute changes in the major risk markers for CVD, in apparently healthy abdominally obese men (CitationMuller et al 2001). This suggested that the secondary metabolic changes, eg, inflammatory factors, which develop as a result of long-standing GHD are of primary importance in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in patients with GHD. Patients with active acromegaly have significantly lower CRP and significantly higher insulin levels than healthy controls and administration of pegvisomant significantly increased CRP to normal levels (CitationSesmilo et al 2002). GH secretory status may be an important determinant of serum CRP levels, but the mechanism and significance of this finding is as yet unknown. Inflammatory markers are predictive of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events (CitationRidker et al 2002; CitationDanesh et al 2004). The metabolic syndrome (MS) is correlated with elevated CRP and a predictor of coronary heart disease and DM (CitationSattar et al 2003). IL-6 concentrations were significantly increased in GHD, compared to BMI-matched and nonobese controls, respectively (CitationLeonsson et al 2003). CRP significantly increased in patients compared to nonobese controls, but not significantly different compared to BMI-matched controls. Age, LDL-cholesterol, and IL-6 were positively correlated, and IGF-I was negatively correlated to arterial intima-media thickness (IMT) in the patient group, but only age and IL-6 were independently related to IMT.

Potential mechanisms

Oxidative stress represents a mechanism leading to the destruction of neuronal and vascular cells.

Oxidative stress occurs as a result of the production of free radicals or reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS consist of entities including the superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion, NO, and peroxynitrite. The production of ROS, such as peroxynitrite and NO, can lead to cell injury through cell membrane lipid destruction and cleavage of DNA (CitationVincent and Maiese 1999). Production of excess ROS can result in the peroxidation of docosahexenoic acid (DHA), a precursor of neuroprotective docosanoids (CitationMukherjee et al 2004). DHA is a fatty acid released from membrane phospholipids and is derived from dietary essential fatty acids. It is involved in memory formation, excitable membrane function, photoreceptor cell biogenesis and function and neuronal signaling. DHA may have a role in modulating IGF-I binding in retinal cells (CitationYorek et al 1989). Neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1) is a DHA-derived mediator that protects the central nervous system (brain and retina) against cell injury-induced oxidative stress, in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. It up-regulates the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, Bcl-2, and Bclxl and decreases pro-apoptotic Bax and Bad expression (CitationBazan 2005).

IGF-I also blocks Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death (Bim) induction and intrinsic death signalling in cerebellar granule neurons (CitationLinseman et al 2002).

Dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons express IGF-I receptors (IGF-IR), and IGF-I activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway. High glucose exposure induces apoptosis, which is inhibited by IGF-I through the PI3K/Akt pathway. IGF-I stimulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway phosphorylates three known Akt effectors: the survival transcription factor cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) and the pro-apoptotic effector proteins glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK-3beta) and forkhead (FKHR). IGF-I regulates survival at the nuclear level through accumulation of phospho-Akt in DRG neuronal nuclei, increased CREB-mediated transcription, and nuclear exclusion of FKHR. High glucose levels increase expression of the pro-apoptotic Bcl protein Bim (a transcriptional target of FKHR). High glucose also induces loss of the initiator caspase-9 and increases caspase-3 cleavage, effects blocked by IGF-I, suggesting that IGF-I prevents apoptosis in DRG neurons by regulating PI3K/Akt pathway effectors, including GSK-3beta, CREB, and FKHR, and by blocking caspase activation (CitationLeinninger et al 2004).

The unique role of IGF-IR in maintaining the balance of death and survival in foetal brown adipocytes, in IGF-IR deficiency has been demonstrated (CitationValverde et al 2004).

A vascular protective role for IGF-I has been suggested because of its ability to stimulate NO production from endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells. IGF-I probably plays a role in aging, atherosclerosis and cerebrovascular disease, cognitive decline, and dementia. In cross sectional studies, low IGF-I levels have been associated with an unfavorable profile of CVD risk factors, such as atherosclerosis, abnormal lipoprotein levels and hypertension, while in prospective studies, lower IGF-I levels predict future development of ischemic heart disease. The fall in the levels of GH (CitationIranmanesh et al 1991) and IGF-I (CitationMilani et al 2004) with aging correlates with cognitive decline and it has been suggested that IGF-I plays a role in the development of dementia. IGF-I is highly expressed within the brain and is essential for normal brain development. IGF-I has anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective effects and promotes projection neuron growth, dendritic arborization and synaptogenesis (CitationCeda et al 2005).

Conclusion

Collectively, these data are consistent with a causal link between the age-related decline in GH and IGF-I levels and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease in senescence. Research into the benefits of replacement hormone therapy is still in its infancy. It was only three decades ago that rhGH became available and significant progress into the somatopause and related pathologies has occurred. Could the future propose the concomitant use of rhGH and rhIGF as has been used in certain refractory cases of diabetes and GH resistance (CitationMauras and Haymond 2005)? The reviews of rhGH replacement in obesity have not been revolutionary (CitationLiu et al 2007). It might be expedient to research the combination of rhGH and rhIGF in the variety of physiological GHD states to determine any beneficial effects. After all, it wasn’t until 1999 that hypothyroidism was identified as being more appropriately treated with tri-iodothyronine (T3) and tetra-iodothyronine (T4), than T4 alone (CitationBunevicius et al 1999).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AbduTAElhaddTAAkberM2001Plasma homocysteine is not a major risk factor for vascular disease in growth hormone deficient adultsClin Endocrinol (Oxf)55635811894975

- AmatoGCarellaCFazioS1993Body composition, bone metabolism, and heart structure and function in growth hormone (GH)-deficient adults before and after GH replacement therapy at low dosesJ Clin Endocrinol Metab77167168263158

- ArgetsingerLSCampbellGSYangX1993Identification of JAK2 as a growth hormone receptor-associated tyrosine kinaseCell74237448343952

- AsmarRBenetosATopouchianJ1995Assessment of arterial distensibility by automatic pulse wave velocity measurement. Validation and clinical application studiesHypertension26485907649586

- AttanasioAFLambertsSWMatrangaAM1997Adult growth hormone-deficient patients demonstrate heterogeneity between childhood onset and adult onset before and during human GH treatmentJ Clin Endocrinol Metab828288989238

- AvolioAPChenSGWangRP1983Effects of ageing on changing arterial compliance and left ventricular load in a northern Chinese urban communityCirculation685086851054

- AvolioAJonesDTafazzoli-ShadpourM1998Quantification of alterations in structure and function of elastin in the arterial mediaHypertension3217059674656

- BalkesteinEJStaessenJAWangJG2001Carotid and femoral artery stiffness in relation to three candidate genes in a white populationHypertension381190711711521

- BankAJWangHHolteJE1996Contribution of collagen, elastin, and smooth muscle to in vivo human brachial artery wall stress and elastic modulusCirculation943263708989139

- BankAJKaiserDRRajalaS1999In vivo human brachial artery elastic mechanics: effects of smooth muscle relaxationCirculation10041710393679

- BaumannG1991Growth hormone heterogeneity: genes, isohormones, variants, and binding proteinsEndocr Rev1242491760996

- BazanNG2005Neuroprotectin D1 (NPD1): a DHA-derived mediator that protects brain and retina against cell injury-induced oxidative stressBrain Pathol151596615912889

- BenetosAAdamopoulosCBureauJM2002Determinants of accelerated progression of arterial stiffness in normotensive subjects and in treated hypertensive subjects over a 6-year periodCirculation1051202711889014

- BengtssonBAEdenSLonnL1993Treatment of adults with growth hormone (GH) deficiency with recombinant human GHJ Clin Endocrinol Metab76309178432773

- BerensonGSWattigneyWATracyRE1992Atherosclerosis of the aorta and coronary arteries and cardiovascular risk factors in persons aged 6 to 30 years and studied at necropsy (The Bogalusa Heart Study)Am J Cardiol7085181529936

- BertovicDAWaddellTKGatzkaCD1999Muscular strength training is associated with low arterial compliance and high pulse pressureHypertension3313859110373221

- BeshyahSAFreemantleCShahiM1995Replacement treatment with biosynthetic human growth hormone in growth hormone-deficient hypopituitary adultsClin Endocrinol (Oxf)4273847889635

- BinnertsASwartGRWilsonJHP1992The effect of growth hormone administration in growth hormone-deficient adults on bone, protein, carbohydrate and lipid homeostasis, as well as body compositionClin Endocrinol377987

- BlacherJAsmarRDjaneS1999aAortic pulse wave velocity as a marker of cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patientsHypertension331111710334796

- BlacherJGuerinAPPannierB1999bImpact of aortic stiffness on survival in end-stage renal diseaseCirculation992434910318666

- BlackMMShusterSBottomsE1972Skin collagen and thickness in acromegaly and hypopituitarismClin Endocrinol125963

- BoutouyriePTropeanoAIAsmarR2002Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of primary coronary events in hypertensive patients: a longitudinal studyHypertension3910511799071

- BramwellJCHillAV1922The velocity of the pulse wave in manProc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci93298306

- BramwellJCHillAVMcSwineyBA1923The velocity of the pulse wave in man in relation to age as measured by the hot wire sphygmographHeart1023355

- BrintonTJKailasamMTWuRA1996Arterial compliance by cuff sphygmomanometer; Application to hypertension and early changes in subjects at genetic riskHypertension285996038843884

- British National Formulary2008A joint publication of the British Medical Association and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain BMJ Group and RPS Publishing [online]. Accessed Jan 18, 2008. URL: http://www.bnf.org.uk/

- BrownRJAdamsJJPelekanosRA2005Model for growth hormone receptor activation based on subunit rotation within a receptor dimerNat Struct Mol Biol128142116116438

- BusseRPohlU1993Fluid shear-stress-dependent stimulation of endothelial cell autacoid release: mechanisms and significance for the control of vascular toneFrangosJAIvesCLPhysical Forces and the Mammalian CellOrlando, FLAcademic Press22348

- BuneviciusRKazanaviciusKZalinkeviciusR1999Effects of thyroxine as compared with thyroxine plus triiodothyronine in patients with hypothyroidismN Engl J Med34042499971866

- CedaGPDall’AglioEMaggioM2005Clinical implications of the reduced activity of the GH-IGF-I axis in older menJ Endocrinol Invest289610016760634

- CocksTMAngusJACampbellJH1985Release and properties of endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF) from endothelial cells in cultureJ Cell Physiol123310203886674

- CohnJNFinkelsteinSMcVeighG1995Non-invasive pulse wave analysis for the early detection of vascular diseaseHypertension2650387649589

- CristDMKranerJC1990Supplemental growth hormone increases the tumor cytotoxic activity of natural killer cells in healthy adults with normal growth hormone secretionMetabolism39132042246974

- CuneoRCSalomonFWilesCMSonksenPH1990Skeletal muscle performance in adults with growth hormone-deficiencyHormone Res3355602245969

- CuneoRCSalomonFWilesCM1991aGrowth hormone treatment in growth hormone-deficient adults. I. Effects on muscle mass and strengthJ Appl Physiol70688942022560

- CuneoRCSalomonFWilesCM1991bGrowth hormone treatment in growth hormone-deficient adults. II. Effects on exercise performanceJ Appl Physiol706957002022561

- CuneoRCSalomonFWilmshurstP1991cCardiovascular effects of growth hormone treatment in growth-hormone-deficient adults: stimulation of the renin-aldosterone systemClin Sci (Lond)81587921661645

- CuneoRCSalomonFWilesCM1993Growth hormone treatment improves serum lipids and lipoproteins in adults with growth hormone-deficiencyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab42151923

- DaneshJWheelerJGHirschfieldGM2004C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart diseaseN Engl J Med35013879715070788

- De BoerHBlokGJVoermanHJ1994Serum lipid levels in growth hormone-deficient menJ Clin Endocrinol Metab43199203

- EichingerSStumpflenAHirschlM1998Hyperhomocysteinemia is a risk factor of recurrent venous thromboembolismThromb Haemost8056699798970

- EvansLMDaviesJSAndersonRA2000The effect of GH replacement on endothelial function and oxidative stress in adult growth hormone deficiencyEur J Endocrinol1422546210700719

- EvansLMDaviesJSGoodfellowJ1999Endothelial dysfunction in hypopituitary adults with growth hormone deficiencyClin Endocrinol5045764

- FerrierKEWaddellTKGatzkaCD2001Aerobic exercise training does not modify large-artery compliance in isolated systolic hypertensionHypertension38222611509480

- FerrierKEMuhlmannMHBaguetJP2002Intensive cholesterol reduction lowers blood pressure and large artery stiffness in isolated systolic hypertensionJ Am Coll Cardiol391020511897445

- FörstermannUNakaneMTraceyWR1993Isoforms of nitric oxide synthase: functions in the cardiovascular systemEur Heart J141057507435

- FowelinJAttvallSLagerI1993Effects of treatment with recombinant human growth hormone on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism in adults with growth hormone deficiencyMetab Clin Exper42144378231841

- FurchgottRF1984The role of endothelium in the responses of vascular smooth muscle to drugsAnn Rev Pharmacol Toxicol24175976203480

- GiannattasioCCattaneoBMMangoniAA1992Changes in arterial compliance induced by physical training in hammer-throwersJ Hypertens10535

- GiannattasioCVincentiAFaillaM2003Effects of heart rate changes on arterial distensibility in humansHypertension42253612913054

- GreenfieldJCPatelDJ1962Relation between pressure and diameter in the ascending aorta of manCirc Res107788113901540

- GreigCAHameedMYoungA2006Skeletal muscle IGF-I isoform expression in healthy women after isometric exerciseGrowth Horm IGF Res16373617107821

- GuerinAPBlacherJPannierB2001Impact of aortic stiffness attenuation on survival of patients in end-stage renal failureCirculation1039879211181474

- HallockPBensonIC1937Studies on the elastic properties of human isolated aortaJ Clin Invest1659560216694507

- HewFLKoschmannMChristopherM1996Insulin resistance in growth hormone-deficient adults: defects in glucose utililization and glycogen synthase activityJ Clin Endocrinol Metab81555648636267

- HoffmanDMCramptonISerniaC1996Short term growth hormone (GH) treatment of GH deficient adults increases body sodium and extracellular water, but not blood pressureJ Clin Endocrinol Metab81112388772586

- HolmesSJEconomouGWhitehouseRW1994Reduced bone mineral density in patients with growth hormone deficiencyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab78669748126140

- HussainMASchmitzOMengelA1993Insulin-like growth factor I stimulates lipid oxidation, reduces protein oxidation, and enhances insulin sensitivity in humansJ Clin Invest922249568227340

- IranmaneshALizarraldeGVelduisJD1991Age and relative adiposity are specific negative determinants of the frequency and amplitude of growth hormone secretory bursts and the half-life of endogenous GH in healthy menJ Clin Endocrinol Metab73108181939523

- JoannidesRRichardVHaefeliWE1997Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of the mechanical properties of peripheral conduit arteries in humansHypertension301465709403568

- KaufmanJMTaelmanPVermeuelenA1992Bone mineral status in growth hormone-deficient males with isolated and multiple pituitary insufficiencies of childhood onsetJ Clin Endocrinol Metab74118231727808

- KellyRPMillasseauSCRitterJM2001Vasoactive drugs influence aortic augmentation index independently of pulse-wave velocity in healthy menHypertension3714293311408390

- KingwellBACameronJDGilliesKJ1995Arterial compliance may influence baroreflex function in athletes and hypertensivesAm J Physiol2684118

- KingwellBABerryKLCameronJD1997aArterial compliance increases after moderate-intensity cyclingAm J Physiol273218691

- KingwellBASherrardBJenningsGL1997bFour weeks of cycle training increases basal production of nitric oxide from the forearmAm J Physiol27210707

- KinlaySCreagerMAFukumotoM2001Endothelium-derived nitric oxide regulates arterial elasticity in human arteries in vivo.Hypertension3810495311711496

- KroekerEJWoodEH1955Comparison of simultaneously recorded central and peripheral arterial pressure pulses during rest, exercise and tilted position in manCirc Res36233213270378

- LajemiMGautierSPoirierO2001aEndothelin gene variants and aortic and cardiac structure in never-treated hypertensivesAm J Hypertens147556011497190

- LajemiMLabatCGautierS2001bAngiotensin II type I receptor-153A/G and 1166A/C gene polymorphisms and increase in aortic stiffness with age in hypertensive subjectsJ Hypertens194071311288810

- LantelmePMestreCLievreM2002Heart rate. An important confounder of pulse wave velocity assessmentHypertension391083712052846

- LaogunAAGoslingRG1982In vivo arterial compliance in manClin Phys Physiol Meas3201127140158

- LaurentSBoutouyriePAsmarR2001Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patientsHypertension3712364111358934

- LehmannEDWattsGFGoslingRG1992aAortic distensibility and hypercholesterolaemiaLancet340117121359256

- LehmannEDGoslingRGSonksenPH1992bArterial wall compliance in diabetesDiabet Med911491563244

- LehmannEDHopkinsKDRaweshA1998Relation between number of cardiovascular risk factors/events and non-invasive Doppler ultrasound assessments of aortic complianceHypertension3256599740627

- LehmannED1999Non-invasive measurements of aortic stiffness: methodological considerationsPathol Biol (Paris)477163010522262

- LeinningerGMBackusCUhlerMD2004Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt effectors mediate insulin-like growth factor-I neuroprotection in dorsal root ganglia neuronsFASEB J181544615319368

- LeonssonMHultheJJohannssonG2003Increased interleukin-6 levels in pituitary-deficient patients are independently related to their carotid intima-media thicknessClin Endocrinol, (Oxf)592425012864803

- Le RoithDScavoLButlerA2001What is the role of circulating IGF-I?Trends Endocrinol Metab12485211167121

- LilienMRSchroderCHLevtchenkoEN2004Growth hormone therapy influences endothelial function in children with renal failurePediatr Nephrol19785915173937

- LinsemanDAPhelpsRABouchardRJ2002Insulin-like growth factor-I blocks Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death (Bim) induction and intrinsic death signaling in cerebellar granule neuronsJ Neurosci2292879712417654

- LiuHBravataDMOlkinI2007Systematic review: the safety and efficacy of growth hormone in the healthy elderlyAnn Intern Med161041517227934

- MalozowskiSTannerLAWysowskiD1993Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor I, and benign intracranial hypertensionN Engl J Med32966568341354

- MaurasNHaymondMW2005Are the metabolic effects of GH and IGF-I separableGrowth Horm and IGF Res15192715701568

- MaurasNAttieKMReiterEO2000High dose recombinant human growth hormone (GH) treatment of GH-deficient patients in puberty increases near-final height: a randomized, multicenter trial. Genentech, Inc., Cooperative Study GroupJ Clin Endocrinol Metab8536536011061518

- McLeodALUrenNGWilkinsonIB2004Non-invasive measures of pulse wave velocity correlate with coronary arterial plaque load in humansJ Hypertens22363815076195

- MealyKBarryMO’MahonyL1998Effects of human recombinant growth hormone (rhGH) on inflammatory responses in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm repairIntensive Care Med24128319539069

- MeaumeSBenetosAHenryOF2001Aortic pulse wave velocity predicts cardiovascular mortality in subjects >70 years of ageArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol2120465011742883

- MedleyTLColeTJGatzkaCD2002Fibrillin-1 genotype is associated with aortic stiffness and disease severity in patients with coronary artery diseaseCirculation105810511854120

- MelmedS2006Medical progress: AcromegalyN Engl J Med1425587317167139

- MeredithITCurrieKEAndersonTJ1996Post ischemic vasodilation in human forearm is dependent on endothelium-derived nitric oxideAm J Physiol270143540

- MilaniDCarmichaelJDWelkowitzJ2004Variability and reliability of single serum IGF-I measurements: impact on determining predictability of risk ratios in disease developmentJ Clin Endocrinol Metab892271415126552

- MiyachiMDonatoAJYamamotoK2003Greater age-related reductions in central arterial compliance in resistance-trained menHypertension41130512511542

- MiyachiMKawanoHSugawaraJ2004Unfavourable effects of resistance training on central arterial compliance. A randomized intervention studyCirculation11028586315492301

- MohiaddinRHUnderwoodSRBogrenHG1989Regional aortic compliance studied by magnetic resonance imaging: the effects of age, training and coronary artery diseaseBr Heart J629062765331

- MoncadaSPalmerRMJHiggsEA1991Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology and pharmacologyPharmacol Rev43109421852778

- MukherjeePKMarcheselliVLSerhanCN2004Neuroprotectin D1: a docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stressProc Natl Acad Sci U S A1018491615152078

- MullerAFLeebeekFWJanssenJA2001Acute effect of pegvisomant on cardiovascular risk markers in healthy men: implications for the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in GH deficiencyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab8651657111701672

- NakaKKTweddelACParthimosD2003Arterial distensibility: acute changes following dynamic exercise in normal subjectsAm J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol2849708

- NapoliRGuardasoleVMatarazzoM2002Growth hormone corrects vascular dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failureJ Am Coll Cardiol3990511755292

- NewbyACHendersonAH1990Stimulus-secretion coupling in vascular endothelial cellsAnn Rev Physiol52661741691907

- [NICE] The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence2003The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [online]Published by the Health Development Agency. Accessed Jan 18, 2008. URL: http://www.nice.org.uk

- NicholsWWO’RourkeMF1998Wave reflectionsMcDonald’s Blood Flow in Arteries: Theoretical, Experimental and Critical PrinciplesLondonEdward Arnold

- O’HalloranDJTsatsoulisAWhitehouseRW1993Increased bone density after recombinant human growth hormone therapy in adults with isolated GH deficiencyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab76134488496328

- OliverJJWebbDJ2003Non-invasive assessment of arterial stiffness and risk of atherosclerotic eventsArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol235546612615661

- O’NealDNKalfasADunningPL1994The effect of 3 months of recombinant human growth hormone (GH) therapy on insulin and glucose-mediated glucose disposal and insulin secretion in GH-deficient adults: a minimal model analysisJ Clin Endocrinol Metab79975837962308

- O’NealDFewFLSikarisK1996Low density lipoprotein particle size in hypopituitary adults receiving conventional growth hormone replacement therapyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab812448548675559

- O'ReillyKERojoFSheQB2006mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates AktCancer Res661500816452206

- O’RourkeMF1992Arterial mechanics and wave reflection with antihy-pertensive therapyJ Hypertens Suppl10439

- O’RourkeMF1999Wave travel and reflection in the arterial systemJ Hypertens1745710100093

- O’RourkeMFPaucaAJiangXJ2001Pulse wave analysisBr J Clin Pharm5150722

- O’RourkeMFStaessenJAVlachopoulosC2002Clinical applications of arterial stiffness; definitions and reference valuesAm J Hypertens154264412022246

- PfeiferMVerhovecMZizekB1999Growth hormone (GH) treatment reverses early atherosclerotic changes in GH-deficient adultsJ Clin Endocrinol Metab84453710022400

- PohlUHoltzJBusseR1986Crucial role of endothelium in the vasodilator response to increased flow in vivoHypertension837473080370

- RamseyMWGoodfellowJJonesCJH1995Endothelial control of arterial distensibility is impaired in chronic heart failureCirculation92321297586306

- RidkerPMRifaiNRoseL2002Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular eventsN Engl J Med34715576512432042

- RileyWAFreedmanDSHiggsNA1986Decreased arterial elasticity associated with cardiovascular disease risk factors in the young. The Bogalusa Heart StudyArteriosclerosis6378863524521

- RosenTEdenSLarsonG1993Cardiovascular risk factors in adult patients with growth hormone deficiencyActa Endocrinol1291952008212983

- RosenTWirenLWilhelmsenL1994Decreased psychological well-being in adult patients with growth hormone deficiencyClin Endocrinol401116

- RowellLBBrengelmannGLBlackmonJR1968Disparities between aortic and peripheral pulse pressures induced by upright exercise and vasomotor changes in manCirculation37954645653055

- Russell-JonesDLWeissbergerAJBowesSB1993The effects of growth hormone on protein metabolism in adult growth hormone-deficient patientsClin Endocrinol3842731

- SafarMEBlacherJPannierB2002Central pulse pressure and mortality in end-stage renal diseaseHypertension39735811897754

- SalomonFCuneoRCHespR1989The effects of treatment with recombinant human growth hormone on body composition and metabolism in adults with growth hormone deficiencyN Engl J Med32117978032687691

- SattarNGawAScherbakovaO2003Metabolic syndrome with and without C-reactive protein as a predictor of coronary heart disease and diabetes in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention StudyCirculation108414912860911

- SesmiloGBillerBMLlevadotJ2000Effects of growth hormone administration on inflammatory and other cardiovascular risk markers in men with growth hormone deficiency. A randomized, controlled clinical trialAnn Intern Med1331112210896637

- SesmiloGFairfieldWPKatznelsonL2002Cardiovascular risk factors in acromegaly before and after normalization of serum IGF-I levels with the GH antagonist pegvisomantJ Clin Endocrinol Metab871692911932303

- SmithJCEvansLMWilkinsonI2002Effects of GH replacement on endothelial function and large-artery stiffness in GH-deficient adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyClin Endocrinol56493501

- SmithJCLaneHDaviesN2003The effects of depot long-acting somatostatin analog on central aortic pressure and arterial stiffness in acromegalyJ Clin Endocrinol Metab8825566112788854

- SnelYEDoergaMEBrummerRM1995Magnetic resonance imaging-assessed adipose tissue and serum lipid and insulin concentrations in GHD adults. Effect of growth hormone replacementArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol15154387583525

- StablerBTurnerJRGirdlerSS1992Reactivity to stress and psychological adjustment in adults with pituitary insufficiencyClin Endocrinol646773

- StehouwerCDJakobsC1998Abnormalities of vascular function in hyperhomocysteinaemia: relationship to atherothrombotic diseaseEur J Pediatr157107119504782

- StewartADMillasseauSCKearneyMT2003Effects of inhibition of basal nitric oxide synthesis on carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity and augmentation index in humansHypertension42915812975386

- Sutton-TyrrellKMackeyRHHolubkovR2001Measurement variation of aortic pulse wave velocity in the elderlyAm J Hypertens14463811368468

- TomiyamaHYamashinaAAraiT2003Influences of age and gender on results of non-invasive brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity measurement/a survey of 12,517 subjectsAtherosclerosis166303912535743

- VaitkeviciusPVFlegJLEngelJH1993Effects of age and aerobic capacity on arterial stiffness in healthy adultsCirculation881456628403292

- ValverdeAMMurCBrownleeM2004Susceptibility to apoptosis in insulin-like growth factor-I receptor-deficient brown adipocytesMol Biol Cell1551011715356271

- Van Buul-OffersSUjedaIVan den BrandeJL1986Biosynthetic somatomedin C increases the length and weight of Snell dwarf micePaediatric Res2082577

- Van DoornumSMcCollGWicksIP2004Atorvastatin reduces arterial stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritisAnn Rheum Dis631571515547080

- Van GuldenerCStehouwerCD2000Hyperhomocysteinemia, vascular pathology, and endothelial dysfunctionSemin Thromb Hemost26281911011845

- VincentAMMaieseK1999Nitric oxide induction of neuronal endonuclease activity in programmed cell deathExp Cell Res2462903009925743

- WennCMNewmanDL1990Arterial tortuosityAustralas Phys Eng Sci Med1367702375702

- WesterbackaJWilkinsonICockcroftJ1999Diminished wave reflection in the aorta: a novel physiological action of insulin on large blood vesselsHypertension3311182210334797

- WilkinsonIBFuchsSAJansenIM1998bReproducibility of pulse wave velocity and augmentation index measured by pulse wave analysisJ Hypertens162079849886900

- WilkinsonIBWebbDJCockcroftJR1999Aortic pulse-wave velocityLancet3541996710622320

- WilkinsonIBMacCallumHHupperetzPC2001Changes in the derived central pressure waveform and pulse pressure in response to angiotensin II and nor-adrenaline in manJ Physiol5305415011158283

- WilkinsonIBHallIRMacCallumH2002aPulse-wave analysis: clinical evaluation of a non-invasive, widely applicable method for assessing endothelial functionArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol221475211788475

- WilkinsonIBQuasemAMcEnieryCM2002bNitric oxide regulates local arterial distensibility in vivo.Circulation105213711790703

- WitJMKooijmanRRijkersGT1993Immunological findings in growth hormone treated patientsHormone Res39107108262470

- YaginumaTAvolioAO’RourkeMF1986Effects of glyceryl trinitrate on peripheral arteries alters left ventricular hydraulic load in manCirc Res2015360

- YorekMLeeneyEDunlapJ1989Effect of fatty acid composition on insulin and IGF-I binding in retinoblastoma cellsInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci302087922676896