Abstract

The association of angiitis of central nervous system (ACNS) with cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) suggests a physiopathological relationship between these two affections. Few cases are reported in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We describe here a clinicopathological case associating ACNS, CAA, and AD. We discuss the aetiology of ACNS and its relationship with cerebral deposition of beta A4 amyloid protein (βA4).

Keywords:

Beta A4 amyloid protein (βA4) cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a frequent disorder which increases with aging (CitationVinters 1987; CitationKumar-Singh 2008). It can be isolated or associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (CitationKumar-Singh 2008). In comparison, primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) is quite rare (CitationKelley 2004; CitationJennette and Falk 2007). Nine percent of reported cases had both PACNS and CAA (CitationKelley 2004; CitationYounger 2004; CitationJennette and Falk 2007). This might suggest a physiopathological relationship between these two vascular disorders (CitationFountain and Eberhard 1996; CitationKumar-Singh 2008). Few previous cases reported the association of PACNS and CAA in AD patients (CitationBrotman et al 2000; CitationJacobs et al 2004). None of these cases was autoptic. We describe here a clinicopathological case associating ACNS, CAA and AD. We discuss the etiology of ACNS and its relationship with cerebral deposition of βA4.

Case report

A 75-year-old woman was referred in acute care for mental deterioration, gait disorder, urinal incontinence, and unusual headache progressing over the six months. The family reported that the short-term memory loss gradually developed over the last two years. The daily activity was disturbed and required the presence of a caregiver. The past medical history included hypertension treated with atenolol. The medical family history was unremarkable.

On admission, the patient was bedridden. Neurological examination revealed a fluctuation of vigilance. She was mute and had a bilateral grasp reflex. There was no motor or sensory deficit. General physical examination was normal. Blood pressure was 150/70 mmHg and temperature was 37 °C. Complete blood count, liver enzymes and serum electrolytes were normal. The results of blood inflammatory test were as follows: erythrocyte sedimentation rate 35 mm/hour, C-reactive protein 620 mg/dL (normal < 100), fibrinogen 51 mg/dL (normal < 40). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunoelectrophoresis were normal. To rule out a diagnosis of meningitis, a lumbar puncture was performed, yielding a clear cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) with 78 erythrocytes/mL, 2 leukocytes/mL, 250 mg/dL protein (normal < 45) with 14.6% IgG in a polyclonal pattern (normal < 10), and 63 mg/dL glucose (normal < 75). Bacterial examination of the CSF did not show any germ and cultures were negative. All serum and CSF tests for infection were unremarkable, including herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2, cytomegalovirus, mycoplasma pneumoniae, Lyme disease, syphilis, mycobacterium tuberculosis, and cryptococcosis. Brain computed tomography (CT) scan showed extensive hypointensities in the white matter in both hemispheres and a mild ventricular enlargement. There was no iodine fixation. Axial brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed T2-weighted high-intensities in the periventricular white matter and was negative in T1-weighted sequences with and without gadolinium infusion. On coronal images, the left hippocampus was atrophic. Search for antinuclear antibody was negative. Because of the severely disabled clinical status and the abnormality of the CSF, an intravenous corticotherapy was initiated seven day after admission with 120 mg dexamethasone per day associated with antibiotics. Vigilance and mutism improved in few days revealing a severe dementia with complete temporo-spatial disorientation. After three weeks of corticotherapy, CSF protein concentration was 46 mg/dL and C-reactive protein was normal. Brain CT scan was unchanged. The neurological status stabilized with a severe dementia. Corticosteroids were progressively tapered over the next five weeks and the patient was transferred to a geriatric rehabilitation hospital. She died four months later of a pulmonary infection.

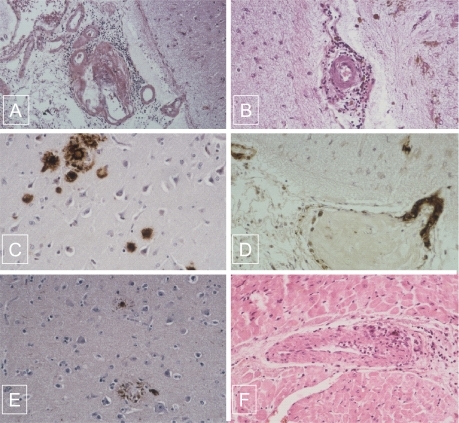

On postmortem examination, the brain weighed 1180 g. Macroscopically, coronal brain slices showed a mild atrophy of the left hippocampus and a moderate enlargement of the lateral ventricles. The cortical band had a normal thickness. Focal small dark red infarcts were disseminated in the subcortical white matter of both hemispheres. The brainstem and cerebellum were normal. The circle of Willis was permeable. Samples of the hippocampus, entorrhinal cortex, middle frontal gyrus, superior and middle temporal gyri, inferior parietal lobule, and midbrain including the basal ganglia were fixed in 10% neutral-formalin and examined by light microscopy. On paraffin-embedded and hematoxylin-eosin-safran and congo red stained sections, lesions consisted in senile plaques, CAA, angiitis, and microinfarcts. Amyloid deposits were present in the neocortex of both cerebral lobes where they appeared as amorphous material in senile plaques. The wall of numerous vessels located in the leptomeningeal space and cortex were also infiltrated by these amyloid deposits. Inflammatory infiltrates consisting in lymphoid cells and macrophages surrounded both amyloid and non amyloid vessels in the leptomeningeal space and less frequently in the cortex (). There were neither multinucleated giant cells nor fibrinoid necrosis. In addition, numerous vessels including some with amyloid deposition showed severe intimal fibrosis occluding the lumen, and suggesting a post inflammatory healing process (). Multiple disseminated small infarcts were observed all over both hemispheres respecting the basal ganglia. They were filled with macrophages and surrounded by siderophages. Immunohistochemical study showed that amyloid deposits, present in the senile plaques and in the wall of vessels including some with an inflammatory infiltrate, were stained with βA4 amyloid antigen (DAKO, Glostrup, Danemark) (). Tau (DAKO) immunolabeled the periphery of the majority of amyloid plaques, and defined neuritic plaques. Tau protein filamentous accumulation was present within the cells bodies of neurons indicating the presence of neurofibrillary tangles, especially in the isocortex (). A semiquantitative assessment of neocortical senile plaques density was estimated as superior to 17 per square millimeter in all the investigated samples of the neo-cortex. The density of neurofibrillary tangles was higher in the hippocampus and the entorrhinal cortex. In the myocardium, the wall of a coronary artery was infiltrated by lymphocytes, mononuclear cells, and giant multinucleated cells (). An interstitial fibrosis was present between the myocytes, likely due to hypertension. Vessel inflammatory changes were not found in the autopsy samples of lung, kidney, liver, spleen, and muscles examined by light microscopy.

Figure 1 A) Association of lymphocytic angiitis and amyloid deposits infiltrating the wall of leptomeningeal vessel and perivascular cuffing of mononuclear cells (hematoxylin-eosin-safran original magnification X 10). B) Mononulear cells surrounding a non amyloid cortical vessel with severe intimal fibrosis occluding the lumen (hematoxylin-eosin-safran original magnification X 20). C) Amyloid deposits present in the senile plaques immunostained for bA4 (original magnification X 40). D) Amyloid deposits present in the wall of vessels in the neocortex immunostained for bA4 (original magnification X 40). E) Neurofibrillary tangles immunostained for tau protein (original magnification X 10). F) Giant cell arteritis in the myocardium (hematoxylin-eosin-safran original magnification X 40).

Discussion

The patient presented with a high neuropathological likelihood of AD according to the National Institute on Aging and Reagan Institute criteria with diffuse senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in all the neocortex (CitationHyman 1998). Assessment for senile plaques corresponded to a “frequent score” according to the CERAD criteria and to a stage V in the Braak and Braak classification (CitationMirra et al 1991). These pathological criteria were associated with a retrospective history of cognitive decline over two years before a rapid and fatal deterioration. In addition, brain MRI showed left hippocampal atrophy. These data were consistent with the pathological study and indicated that the patient developed AD prior to hospitalization.

In our case, the AD was associated with two cerebrovascular pathologies. The first was CAA as demonstrated by Congo red staining of blood vessels and βA4 deposition in the wall of vessels restricted to the brain. The second was a cerebral angiitis which probably explains most of the terminal clinical manifestations including gait disorder, unusual and persisting headache, diffuse white matter lesions on brain imaging, and high CSF protein concentration. There are several arguments to consider that it was a PACNS and not a secondary ACNS. The clinical presentation of PACNS frequently includes dementia and headache. CSF protein concentration is elevated in 80% of cases. Cerebral imaging usually shows multiple cerebral infarcts, but isolated white matter abnormalities have also been reported (CitationFountain and Eberhard 1996; CitationBrotman et al 2000; CitationJacobs et al 2004). None of these signs are specific and pathological study only is able to ascertain the diagnosis. Lesions consist in inflammatory cell infiltrates of small and middle sized leptomeningeal and cortical arteries with cortical and subcortical infarcts (CitationYounger 2004). A granulomatous reaction considered as typical of PACNS occurs in only half of the pathologically proven cases (CitationKelley 2004; CitationYounger 2004). In the others, inflammatory cells consist in lymphocytes and monocytes (CitationKelley 2004; CitationJennette and Falk 2007). In the case reported herein, inflammatory infiltrates were composed of mononuclear cells predominating around the vessels. However, in the myocardium, a typical granulomatous inflammatory reaction was present around some vessels. Asymptomatic extracerebral localization of the angiitic process is possible. The diagnosis of PACNS is usually based on two cerebral examinations which are angiographic changes and positive cerebral biopsy (CitationFountain and Eberhard 1996; CitationKelley 2004; CitationYounger 2004). It has been reported in carefully studied autopsy cases of PACNS that an asymptomatic extension of the inflammatory process is possible and probably not rare (CitationLie 1997). Our case is in concordance with this assumption. Furthermore, there was no argument for a secondary cerebral angiitis due to infection, collagen-vascular disease or drug reaction (CitationKelley 2004; CitationYounger 2004). In addition, an Aβ-related angiitis (ABRA) could be also discussed. ABRA has been defined by CitationScolding and colleagues (2005) as an association of a PACNS with CCA. ABRA affects older subjects compared to PACNS. Treatment of ACNS mainly depends on steroids and cyclophosphamide (CitationYounger 2005). In our patient, steroids resulted in a partial improvement of the clinical status and normalization of the CSF and C-reactive protein indicating that the clinical deterioration of the late phase of the evolution was probably due to the cerebral angiitis.

Primary CAA is a frequent pathological process in aging causing mainly cerebral hemorrhage or more rarely an ischemic leucoencephalopathy (CitationVinters 1987; CitationKumar-Singh 2008). A hypothetical causal relationship possibly exists between CAA and PACNS as both simultaneously occurred in seventeen reported cases of the literature representing almost 9% of patients with PACNS (CitationKelley 2004; CitationYounger 2004; CitationJennette and Falk 2007). It has been hypothesized that βA4 deposits may trigger an inflammatory process by activating the cytokine cascade, stimulating macrophages, and inducing an inflammatory reaction that can affect both amyloid and nonamyloid vessels (CitationFountain and Eberhard 1996). CAA also occurs in up to 90% of cases of AD and is more frequent and severe in older patients (CitationVinters 1987; CitationKumar-Singh 2008). It is correlated with a higher frequency of hemorrhages and ischemic lesions. The pathophysiology of βA4 deposition in the CAA of AD is unknown but is probably different from that of βA4 deposition in senile plaques. Despite the high frequency of CAA in AD, the association of PACNS with CAA in the context of AD has not been reported so far (CitationBrotman et al 2000; CitationJacobs et al 2004). In addition, although recent data suggest that patients with AD are prone to develop cerebrovascular diseases, autopsy series have not shown an abnormal frequency of PACNS in AD (CitationJoachim et al 1988). In our patient, the relations between AD/CAA and PACNS remain unknown. A fortuitous association is possible. Alternatively, immune factors may have triggered the angiitis in a similar way as hypothesized in patients with CAA and PACNS. In this respect, the role of immunity and particularly complement fractions and cytokines has been discussed in AD (CitationDickson et al 1996; CitationGold et al 1998). However, the uniqueness of our case with AD in comparison with the relative frequency of the association of PACNS and primary CAA without AD suggests a different ability of amyloid deposits to trigger an immune reaction in AD.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BrotmanDJEberhartCGBurgerPC2000Primary angiitis of the central nervous system and Alzheimer’s disease: clinically and pathologically evident in a single patientJ Rheumatol272935711128690

- DicksonDWLeeSCBrosmanCF1996Neuroimmunology of aging and Alzheimer’s disease with emphasis on cytokinesRansckoffRMBenvenisteENCytokines and the CNSBoca Raton, FLCRC Press23967

- FountainNBEberhardDA1996Primary angiitis of the central nervous system associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy: report of two cases and review of the literatureNeurology4619078559373

- GoldGGiannakopoulosPBourasC1998Re-evaluating the role of vascular changes in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementiaEur Neurol4012199748669

- HymanB1998New neuropathological criteria for Alzheimer diseaseArch Neurol55117469740109

- JacobsDALiuGTNelsonPT2004Primary central nervous system angiitis, amyloid angiopathy, and Alzheimer’s pathology presenting with Balint’s syndromeSurv Ophthalmol49454915231402

- JennetteJCFalkRJ2007Nosology of primary vasculitisCurr Opin Rheumatol1910617143090

- JoachimCLMorrisJHSelkoeDJ1988Clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease: autopsy results in 150 casesAnn Neurol245063415200 KelleyRE2004CNS vasculitisFront Biosci99465514766421

- Kumar-SinghS2008Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: pathogenetic mechanisms and link to dense amyloid plaquesGenes Brain Behav7Suppl 1678218184371

- LieJT1997Classification and histopathologic spectrum of central nervous system vasculitisYoungersDSVaselloJVasculitis and the Nervous SystemPhiladelphia, PANeurologic Clinics1580519

- MirraSSHeymanAMcKeelD1991The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s diseaseNeurology41479862011243

- ScoldingNJJosephFKirbyPA2005Abeta-related angiitis: primary angiitis of the central nervous system associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathyBrain1285001515659428

- VintersHV1987Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. A critical reviewStroke18311243551211

- YoungerDS2004Vasculitis of the nervous systemCurr Opin Neurol173173615167068