Abstract

Acute aortic dissection is a medical emergency with high morbidity and mortality requiring emergent diagnosis and therapy. A 79-year-old woman with acute aortic dissection due to percutaneous coronary intervention was presented. Aortic dissection is an uncommon but potentially lethal illness that can present in an occult manner making the initial diagnosis difficult. Aggressive medical management is mandatory, as well as urgent diagnostic testing and cardiothoracic consultation.

Aortic dissection is the most common and most lethal catastrophe that can involve the aorta (CitationFuster and Ip 1991). It is estimated to occur at a rate of >2000 new cases per year (CitationVecht et al 1980). It is several times more common than a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (CitationKouchoukos and Dougenis 1997). Aortic dissections are two times more common in males, and most commonly occur between the ages of 50 and 70 years (CitationHagan et al 2000). Aortic dissection is rare in patients younger than 40 years of age, unless it is associated with a specific predisposing syndrome such as Marfan’s disease, Ehlers-Danlos, congenital heart disease, family history, bicuspid valve, pregnancy, coarctation of the aorta, Turner’s disease, use of an illicit drug such as cocaine, or trauma (CitationFarina and Kwiatkowski 2003).

Case report

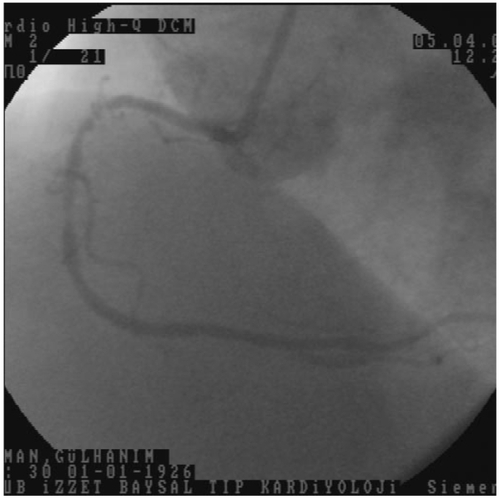

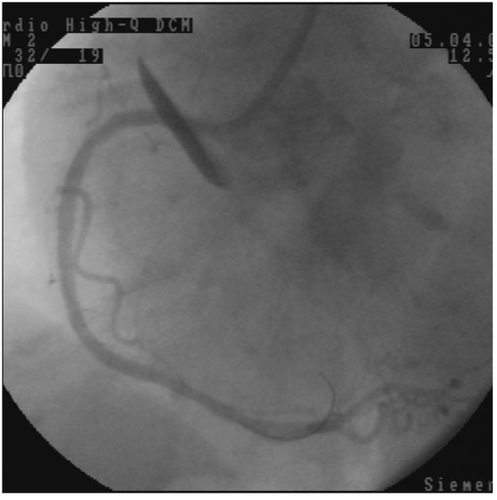

A 79-year-old woman was admitted for acute coronary syndrome. In coronary angiography, the left main coronary artery was normal. There were 50% stenosis in the first diagonal branch of left anterior descending coronary artery, 40% stenosis after first diagonal branch, and 80% stenosis after second diagonal branch in the left anterior descending coronary artery. There were 90% stenosis after first obtuse marginal branch and 95% stenosis after third obtuse marginal branch of left circumflex coronary artery. There were 90% stenosis before right ventricular branch, 80% stenosis after right ventricular branch, and 60% stenosis in posterolateral branch of right coronary artery. First, we decided on percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for right coronary artery because it was mainly responsible for the patient’s complaint (). We crossed the two occlusions with a 0.014 floppy guidewire (Choice, Boston Scientific USA), then we dilated the lesion before right ventricular branch of right coronary artery with a 2.0 × 20 mm viva balloon, (Scimed, Boston Scientific, Ireland) at 16 atmospheres 30 sec. Then, we implant a 3.5 × 23 mm (Meo:DrugStar, paclitaxel eluting stent, Germany) at 10 atmospheres. We decided to direct stent implantation for the second lesion. During the coronary stent implantation, the coronary stent system pushed the guiding catheter into the aorta, while passing to right coronary artery from guiding catheter. We implanted a 3.0 × 23 mm (Meo:DrugStar, paclitaxel eluting stent, Germany) at 16 atmospheres. At the end of the procedure, we noticed an aortic dissection in the proximal of the aorta (DeBakey type II, Stanford type A), while giving the dye for control angiography of right coronary artery (). We finished the PCI procedure. Because of hemodynamic stability, we decided to follow the aortic dissection medically, so we took the patient to the coronary care unit. Amlodipine 5 mg/day, gliclazide MR 30 mg/day, metaprolol 25 mg/day, enteric-coated aspirine 100 mg/day, and clopidogrel 75 mg/day were given to the patient. The next day, her echocardiographic examination showed increased echogenity in the proximal part of aorta. One week later, the echogenity in the same part was smaller, and one month later, the echogenity was absent in the proximal part of aorta.

Discussion

Acute aortic syndrome includes aortic dissection, intramural hematoma (IMH), and symptomatic aortic ulcer. Propagation of the dissection can proceed in anterograde or retrograde fashion from the initial tear involving side branches and causing complications such as malperfusion syndromes, tamponade, or aortic valve insufficiency. Common predisposing factors in the International Registry of Aortic Dissection (IRAD) were hypertension in 72% of cases, followed by atherosclerosis in 31% and previous cardiac surgery in 18%. Analysis of the young patients with dissection (<40 years of age) revealed that younger patients were less likely to have a history of hypertension (34%) or atherosclerosis (1%), but were more likely to have Marfan syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, and/or prior aortic surgery (CitationFarina and Kwaitkowski 2003).

The Stanford classification of aortic dissection distinguishes between type A and type B. Type A means the dissection includes the ascending aorta, a type B dissection does not involve the ascending aorta. The De Bakey classification subdivides the dissection process further: a type I dissection involves the entire aorta, a type II dissection involves the ascending aorta, and a type III dissection involves the descending aorta. The first attempt to further subdivide the De Bakey classification was made by Reul and Cooley (), differentiating from thoracic abdominal type III dissection. Subdividing into proximal and distal or ascending and descending aortic dissections is also common (CitationErbel et al 2001).

New studies demonstrated that intramural hemorrhage, intramural hematoma, and aortic ulcers may be signs of evolving dissections or dissection subtypes. Consequently, a new differention has been proposed (CitationErbel et al 2001).

Class 1: Classical aortic dissection with an intimal flap between true and false lumen.

Class 2: Medial disruption with formation of intramural hematoma/hemorrhage.

Class 3: Discrete/subtle dissection without hematoma, eccentric bulge at tear site.

Class 4: Plaque rupture leading to ulceration, penetrating aortic atherosclerotic ulcer with surrounding hematoma, usually subadventitial.

Class 5: Iatrogenic and traumatic dissection.

All classes of dissection can be seen in their acute and chronic stages; chronic dissections are considered to be present if >14 days have elapsed since the acute event or if they are found occasionally (CitationErbel et al 2001).

Diagnostic imaging studies in the setting of suspected aortic dissection is aimed to rapidly confirm or exclude the diagnosis, classify the extend of the dissection, and assess the emergent nature of the problem, with correct classification in distal or proximal dissection being of paramount importance. For confirmation of the diagnosis patients often require more than one noninvasive imaging study to characterize aortic dissection, with computed tomography (CT) used in 61% of cases, echocardiography in 33%, aortography in 4%, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in only 2%. Upon admission in the emergent setting, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is useful in identifying proximal aortic dissection and thus to diagnose type A dissection in patients with shock (CitationInce and Nienaber 2007).

Besides imaging, biomarkers for early detection of aortic dissection have recently attracted interest; a promising assay checks for circulating smooth muscle myosin heavy chain protein, a protein that is released from damaged aortic medial smooth muscle and elevated in the early hours of acute aortic dissection. Additional biochemical markers such as acute phase reactants, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, soluble elastin fragments, and D-dimer are also being studied (CitationInce and Nienaber 2007).

Acute dissections involving the ascending aorta are considered surgical emergencies requiring swift repair of the aortic root or reconstruction of the ascending aorta and the arch to improve prognosis. In contrast, dissections confined to the descending aorta are treated medically unless progression of dissection, intractable pain, organ malperfusion, or extraaortic blood is demonstrated (CitationInce and Nienaber 2007).

In the initial phase after impact the therapeutic objective is normalization of blood pressure and lowering of the left ventricular ejection force (dP/dt), with β-blockers, to the lowest tolerable levels while ensuring adequate cerebral, coronary, and renal perfusion. For most patients, a blood pressure between 100–120 mmHg at a heart rate <60 beats/min is achievable. In patients intolerant to β-blockers because of asthma, bradycardia, or signs of heart failure, vasodilators, and short acting calcium channel blockers are valuable options. In patients, with low and even normal blood pressure at presentation, possible volume depletion from hemorrhage and/or pericardial effusion must be considered. These patients may benefit from intubation before rapid tomographic imaging for confirmatory diagnosis and swift treatment. If pericardial tamponade is diagnosed, pericardiocentesis before surgery can be harmful because it may counteract hypotonic hemostasis and eventually cause more pericardial bleeding and intractable tamponade (CitationInce and Nienaber 2007).

Acute proximal dissection (Stanford type A or DeBakey type I or II) are to be considered a surgical emergency because of the high risk of life threatening complications. Medical management alone has a mortality of nearly 20% by 24 h and 30% by 48 h. Surgical treatment aims to prevent lethal complications such as aortic rupture, stroke, visceral ischemia, cardiac tamponade, and circulatory failure. With a history of 50 years the surgical concept is to excise the intimal tear to close any entry to false lumen, and to reconstruct the aorta with interposition of a synthetic graft with or without reimplantation of coronary arteries. In addition, restoration of aortic valve competence is needed with aortic insufficiency by resuspension of the native aortic valve or valve replacement. Patients with uncomplicated aortic dissections confined to the descending thoracic aorta (Stanford type B or DeBakey type III) are at present preferentially treated conservatively, but may be considered candidates for a reconstructive strategy such as endovascular scaffolding in the near future (CitationInce and Nienaber 2007).

Due to the high mortality of aortic dissection in the acute stage, the survival rate in both type A and B (type I-III) dissection is very low. Forty years ago, the 24 h mortality was 21%. A dramatic improvement can be observed due to medical and surgical therapy over the last 30 years. The European Cooperative study group reported a 1 year survival rate of 52%, 69%, and 70% in type A (type I, type II) and type B (type III) dissection, respectively. This decreased to 48%, 50%, and 60% after 2 years (CitationErbel et al 2001).

Aortic dissection is an uncommon but potentially lethal illness that can present in an occult manner making the initial diagnosis difficult. Aggressive medical management is mandatory, as well as urgent diagnostic testing and cardiothoracic consultation. With early diagnosis, mortality may be significantly reduced. If the hemodynamic stability is not changed, the patient may be followed medically.

References

- FusterVIpJHMedical aspects of acute aortic dissectionSemin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg19913219241958742

- VechtRJBestermanEMBromleyLIAcute dissection of the aorta: long-term review and managementLancet1980160109116101454

- KouchoukosNTDougenisDMedical progress: surgery of the thoracic aortaN Engl J Med19973361876889197217

- HaganPGNienaberCAIsselbacherEMInternational registry of acute aortic dissection (IRAD). New insights into an old diseaseJAMA200028389710685714

- FarinaGAKwiatkowskiTAortic dissectionPrim Care Update Ob/Gyns2003101616

- InceHNienaberCADiagnosis and management of patients with aortic dissectionHeart2007932667017228080

- ErbelRAlfonsoFBoileauCDiagnosis and management of aortic dissection. Recommendations of the Task Force on Aortic Dissection, European Society of CardiologyEur Heart J20012216428111511117