Abstract

There continues to be a need for improved medical management of diabetes patients with hypertension in primary care. While several care models have shown effectiveness in achieving various outcomes among these patients, it remains unclear what care model is most effective in improving blood pressure control in primary care. In this prospective study, 54 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and blood pressure of >140/90 identified through the registry, were randomized into three groups. Group A attended a nurse educator-conducted class on diabetes and hypertension, group B attended the same class and was asked to monitor their home blood pressure using provided device, and group C served as control (usual care). Of the 24 subjects who completed the study, only 20% achieved the target blood pressure of <130/80 and there was no statistical difference in mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures among the three groups (p > 0.05). Efforts to intensify management of hypertension among type 2 diabetes patients did not result in better blood pressure control compared to usual care. Studies looking into factors which limit patients’ participation in group classes and determining patients’ preferences in disease management would be helpful in ensuring success of any chronic disease management program.

Background

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of premature mortality among patients with diabetes, with heart disease accounting for more than half of these deaths. Hypertension is common in patients with type 2 diabetes, with a prevalence of 40%–60% over the age range of 45 to 75 and contributes to their risk of cardiovascular disease.Citation1 The association of elevated blood pressure with risk is amplified in patients with diabetes who have roughly a doubling of absolute risk compared with patients without diabetes at each systolic blood pressure level.

Several trials have documented the importance of blood pressure control in reducing the risk of cardiovascular and renal disease among patients with diabetes.Citation2–Citation5 Results of these trials supported an aggressive approach to the treatment of hypertension among patients with diabetes leading to a recommended blood pressure goal of <130/80.Citation5–Citation7 This requires the use of at least two agents in most patients with the consensus of having a renin–angiotensin system blocker as first-line treatment.Citation6–Citation8

Effective control of blood pressure among patients with diabetes continues to pose a clinical practice challenge. Hypertensive diabetes patients are still frequently not treated to their goal blood pressure; studies demonstrated that this group of patients has worse blood pressure control than patients with hypertension but without diabetes mellitus.Citation9,Citation10 Clinical uncertainty about the true blood pressure value was a major reason identified as to why providers do not intensify antihypertensive therapy among diabetes patients.Citation11 Clearly, there is room for outpatient practice improvement.

Several care models have been shown to be effective at improving outcomes among diabetes patients. Group education classes have been successful in enhancing diabetes care.Citation12,Citation13 A case study reported achievement of blood pressure control in majority of patients with diabetes secondary to nursing staff involvement in care management and use of medications concomitant with guidelines.Citation14 Another study found that a nurse-led hypertension clinic was more effective for patients with type 2 diabetes and uncontrolled hypertension compared to conventional care.Citation15 It is unclear which of these models is most effective in achieving hypertension control among diabetes patients in a primary care setting.

In the recent years, the SHEAF trial and other studies have thrown another complexity into hypertension control by showing that office blood pressure readings were inaccurate in 22% of treated hypertensive patients. Subsequent studies showed that use of home blood pressure measurement by a physician/nurse team has the potential to significantly improve long-term hypertension control rates and that self-monitoring of blood pressure promoted achievement of target blood pressure in primary health care.Citation16,Citation17 One study even showed ambulatory blood pressure to be a better marker than clinic blood pressure in predicting cardiovascular events in patients with or without type 2 diabetes.Citation18 Thus, self-monitored or home blood pressure measurement is becoming a potentially very powerful and cost-effective tool in the management of hypertension.

Disease registries are powerful tools that allow identification of high-risk patients within a defined population.Citation19 A previously published study utilized the diabetes registry to evaluate implementation strategies aimed at improving glycosylated hemoglobin and low-density lipoprotein testing rates among poorly controlled diabetes patients.Citation20

Using the diabetes registry to identify diabetes patients with hypertension who meet our target population, we conducted a study to compare three practice care models, two using intensified management and one using usual care, with the aim of achieving target blood pressure as recommended by current practice guidelines. We hypothesized that (1) participation of diabetes patients with uncontrolled blood pressure (blood pressure >140/90) in an intensified care management model using a specific intervention would result in improved blood pressure control among this group of patients compared to conventional care, that (2) the percentage of diabetes patients with uncontrolled hypertension achieving target blood pressure readings (blood pressure <130/80) will be significantly higher among those randomized to an intensified model compared to conventional care, and that (3) different care delivery models would lead to varying degrees of blood pressure improvement among diabetes patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Methods

Design

This was a prospective randomized control trial conducted in a multispecialty clinic in the midwestern United States. Eligible subjects were primary care paneled patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and blood pressure above determined cut-off who were identified using the diabetes registry. Nursing home patients were excluded. Study duration was six months. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Registry tool

The registry is an institutionally developed centralized database of diabetes patients who were identified based on administrative billing data that used International Classification of Diseases 9th revision codes (ICD-9 CM) for the diagnosis of diabetes. Provider patient lists are pulled from the clinic’s generalized patient appointment system, which identifies a patient’s primary care provider. Before being included in the registry, all patient records were reviewed by a registered nurse to verify that they are diabetics and are assigned to the correct physician. The registry is interfaced with other clinical information systems which allow entry of patient data such as blood pressure and laboratory test results. Blood pressure data are captured and updated weekly from the electronic medical record (EMR). It became available to providers beginning in early 2000.

Blood pressure cut-off

To determine the blood pressure threshold for identification of our target population from the diabetes registry, we did a retrospective analysis of three separate blood pressure readings in three groups of 20 randomly selected patients using targets of 130/80, 140/90, and 150/90. Using 130/80 as cut-off, 100% of 20 patients had blood pressure of greater than 130/80 with one reading but only 45% was consistently above target with two out of three readings. At a cut-off of 140/90, 50% were consistently above target with two readings. With 150/90 as cut-off, 100% was above it at first reading and 65% was still above target in two of three readings. However, this group constitutes less than a third of patients in the registry with above target blood pressure. We therefore selected to use a cut-off of 140/90 as at least 50% of the 60 randomly selected diabetes patients in the registry were consistently above this target in two out of three readings.

Intervention

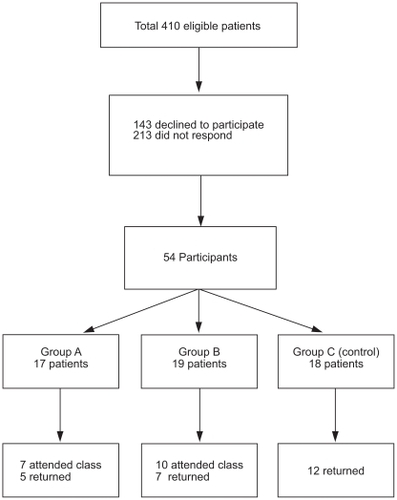

Four hundred ten patients qualified and were sent a letter of invitation to participate. There were 197 responders of whom 143 refused to participate and only 54 consented (). After stratification based on gender, age (≤60 years, >60 years) and hemoglobin A1C level (≤7%, >7%), each of the participant was randomized to one of three groups with two arms using practice care models and the third arm serving as control group. Group A patients were invited to participate in a class focusing on hypertension in diabetes. Group B patients were also invited to participate in the class; in addition, they were given automated blood pressure devices and asked to track their home blood pressure readings and record them in a booklet to be submitted at the end of the study. Three classes were set up to allow for flexibility in scheduling and each participant in the two groups was asked to attend one class. The classes were conducted by a diabetes nurse educator using structured format. The automated blood pressure device (Life Source UA-767 Plus; Life Source, San Jose, CA, USA) had been clinically validated according to British Hypertension Society (BHS) standards and had met the limits set by the American National Standards Institute. Group C patients did not receive any invitation. All study participants continued to see their primary care physicians for usual care. No interim follow-up was done during the study period. Since the study focused on comparing practice models, participants’ use of pharmacologic therapy for blood pressure control was not captured.

Seventeen patients were randomized to group A, 19 to group B, and 18 to group C.

Group A and B subjects had their blood pressure checked by a registered nurse (MH) during class attendance using standardized blood pressure measurement protocol used in the clinic (copy available upon request). Clinic blood pressure readings correlate closely with registry data. Those in group B received additional instruction on home blood pressure monitoring from the registered nurse based on the clinic’s patient education pamphlet entitled “Measuring Your Blood Pressure at Home” (MC3031-03). A copy of the pamphlet was also provided. All study participants were asked to return for a nurse blood pressure recheck after six months, again following the standardized blood pressure measurement protocol. Group B patients were also asked to bring back their booklet with home blood pressure readings.

Primary outcome measure was the percentage of study subjects who achieved blood pressure goal of <130/80 within six months as measured in clinic during the return visit. Secondary outcome measures were mean arterial pressures of participants in each study arm, and number of nurse (RN) and physician (MD) visits for each patient in each group.

Statistical method

Mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variable or frequency (percentage %) for categorical variable was compared among the three groups using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Pearson’s chi-squared test, respectively. Post hoc pair-wise comparisons were applied using the Scheffe’s significant criteria.Citation21 was prepared using all available data with intention-to-treat analysis while showed data only on those who had completed the study. Multivariate logistic model approach was also used to find possible factors that predicted achievement of target blood pressure goals. The analysis was performed using intent-to-treat and per protocol approaches. Participants who did not complete the entire six-month study period or failed to return at six-month follow-up were considered dropouts and were excluded in the per protocol analysis, but included in the intent-to-treat analysis.

Table 1 Intention-to-treat analyses

Table 3 Per protocol analyses (subjects who completed the study)

When sample size is 18 in each group, we would have 80% power to detect at the 0.050 level an effect size of 0.1893 using one-way ANOVA. With the same sample size, a 0.050 level Pearson’s chi-squared test will have 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 9.4 in proportions. All analyses were handled by SAS software (version 9.1.3; SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA). Any three-group comparison p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Of the 410 eligible patients who were invited to participate, 143 (34.9%) declined participation and 54 (13.2%) consented. There were 213 (52.0%) nonresponders. We did not have gender and age information for the nonresponders as well as age information for nonparticipants. Gender was not different between those who consented to participate and the decliners (p = 0.87). The state where the patients lived were not different among participants, decliners, and nonresponders (p = 0.95). The participants however had slightly lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures than others (p = 0.03 and p = 0.06, respectively).

Twenty-eight (52%) of the 54 participants are female; 41 (76%) are aged over 60 years and 22 (41%) have hemoglobin A1C level above 7% (). From the registry, study participants had a mean systolic blood pressure of 149.79 and a mean diastolic blood pressure of 73.89. There was no difference in baseline mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure among the three groups. Seven patients randomized to group A attended the class; only five returned after six months for blood pressure recheck. Ten patients in group B attended the class and took home an automated blood pressure device; seven returned after six months. Of the 18 patients randomized to Group C, 12 returned, one died, and two were too ill to leave home ().

Table 2 Baseline demographics

After six months, only 20% (n = 5) of the 24 subjects who completed the study achieved the target blood pressure of <130/80. There was no difference in the percentage of subjects achieving target blood pressure among the three groups (p > 0.05). Using both intention-to treat and per protocol analyses, there was no significant difference in mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures among the three groups of study participants after six months (, ). Interestingly, those in groups B and C had lower mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure than those in group A; however they are still not significant. Seven participants in group B returned their booklet with home blood pressure recordings at the end of the study period. There was variation in the number of home blood pressure readings among the seven participants with total readings ranging from 38 to 156. The mean systolic and diastolic home blood pressure readings in five of the seven participants was <130/80.

We compared the number of RN and MD visits during the study period for each study participant and found no difference among the three groups. We did not find any significant factor, using the multivariate logistic model that predicted achievement of target blood pressure goal. We considered each participant’s baseline systolic blood pressure, baseline diastolic blood pressure, BMI, RN, and MD visits.

Discussion

In this study, only 10% of randomized subjects (n = 54) with uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes achieved the target blood pressure of <130/60 after six months. Our study failed to show a statistical difference in mean blood pressure readings after six months among the subjects randomized into three study groups. Those randomized into a more intensive management; ie, groups A and B did not have significant improvement in blood pressure control compared to those under usual care. Different care delivery models (usual care plus education, usual care plus education and home blood pressure self monitoring, or usual care alone) did not result in varying degrees of blood pressure improvement among diabetes patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Given our small sample size, it was not surprising to see no statistically significant differences among the study groups. We were also underpowered as only half of the randomized participants completed the study.

Seven out of the 19 participants who were randomized to group B returned after six months with recorded home blood pressure readings, five subjects had mean blood pressure readings below 130/80. Outcome blood pressure readings in this study were obtained during a return clinic visit using standard protocol. Only two study participants in group B met target pressure on return clinic blood pressure check. This observation is consistent with previously reported discrepancies between office and home blood pressure readings, home or ambulatory readings potentially being more accurate. Evaluating the achievement of recommended blood pressure among diabetics with uncontrolled hypertension through different delivery care models using home blood pressure recordings may therefore be a more effective outcome measure.

Self-management is an essential component of chronic disease model. We failed to see a trend towards increased self-activation among participants in the practice model arms. Participation in education and tracking blood pressure readings at home did not increase patient’s likelihood of seeing a health care provider more often than those under conventional care. A characteristic defined as “I can take charge” and reflected in an individual’s proactive behavior of seeking more information from health care providers has been equated with high self-efficacy and adherence to medication.Citation22 In this study, we incorporated chronic disease model components such as use of registry and allied professionals to achieve our stated aim.Citation23 It was apparent that without the component of patient self-management, attainment of target blood pressure would be difficult. Indeed, evidence has supported the effectiveness of self-management training in diabetes care.Citation24,Citation25

We are not aware of any previously reported study that has compared blood pressure control among patients with diabetes mellitus and uncontrolled hypertension who were identified through the registry and randomized into different delivery care models. Despite its negative outcome, our study is the first of such kind. Our study was limited by its lack of power due to a small sample size and short follow-up of six months. We would recommend redesigning a larger study with a longer follow-up duration based on our experience in this pilot study.

As we continue to be challenged on how to best manage our patients with chronic diseases in the changing health care environment and patient population profile, there remains a great need to create innovative practice models. Given our study results, the next step perhaps is to focus on identifying factors that create barriers to patients’ participation into care initiatives and surveying patients regarding their preferences in care delivery and disease management. Valuable data can then be obtained that may help guide educators and practitioners into structuring a practice care model that enhances patients’ engagement in their health and deliver efficient care with sustained outcomes.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study GroupTight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38BMJ19983177037139732337

- EstacioROJeffersBWHiattWRBiggerstaffSLThe effect of nisoldipine as compared with enalapril on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes and hypertensionN Engl J Med1998338106456529486993

- HanssonLZanchettiACarruthersSGDahlofBEffects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: Principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomized trialLancet19983519118175517629635947

- MogensenCENew treatment guidelines for a patient with diabetes and hypertensionJl Hypertens Suppl2003211S25S30

- PrisantLMDiabetes mellitus and hypertension: a mandate for intense treatment according to new guidelinesAm J Ther2003105 36336912975721

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRNational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating CommitteeThe Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 reportJAMA2003289192560257212748199

- American Diabetes AssociationTreatment of hypertension in adults with diabetesDiabetes Care200225119920111772916

- American Diabetes AssociationHypertension management in adults with diabetesDiabetes Care200427Suppl 1S65S7114693929

- GodleyPJMaueSKFarrellyEWFrechFThe need for improved medical management of patients with concomitant hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitusAm J Manag Care200511420621015839181

- BerlowitzDRAshASHickeyECGlickmanMFriedmanRKaderBHypertension management in patients with diabetes: the need for more aggressive therapyDiabetes Care200326235535912547862

- KerrEAZikmund-FisherBJKlamerusMLThe role of clinical uncertainty in treatment decisions for diabetes patients with uncontrolled blood pressureAnn Intern Med20081481071772718490685

- HellerSRClarkePDalyHDavisIGroup education for obese patients with type 2 diabetes: Greater success at less costDiabet Med1988565525562974778

- DavisMJHellerSSkinnerTCCampbellMJEffectiveness of the diabetes education and self-management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: cluster randomized controlled trialBMJ2008336764249149518276664

- WessellAMOrsteinSMNietertPJWilsonJPBrooksAAchieving blood pressure control in patients with diabetes: a case study in primary careTop in Health Inf Manage200324137

- DenverEABarnardMWoolfsonRGEarleKAManagement of uncontrolled hypertension in a nurse-led clinic compared to conventional care for patients with type 2 diabetesDiabetes Care20032682256226012882845

- HalmeLVesalainenRKaajaMKantolaISelf-monitoring of blood pressure promotes achievement of blood pressure target in primary health careAm J Hypertens200518111415142016280273

- CanzenelloVJensenPLSchwartzLLWorraJBKleinLKImproved blood pressure control with a physician-nurse team and home blood pressure measurementMayo Clin Proc2005801313615667026

- EquchiKPickeringTGHoshideSAmbulatory blood pressure is a better marker than clinic blood pressure in predicting cardiovascular events in patients with/without type 2 diabetesAm J Hypertens200821444345018292756

- WeberVBloomFPierdonSWoodCEmploying the electronic health record to improve diabetes care: a multifaceted intervention in an integrated delivery systemJ Gen Intern Med200823437938218373133

- StroebelRScheitelSMFitzJSA randomized trial of three diabetes registry implementation strategies in a community internal medicine practiceJt Comm J Qual Improv200228844145012174408

- SchefféHA method for judging all contrasts in the analysis of varianceBiometrika1953401/287104

- HughesCMillerEFRPeatJMcElnayJCThe effects of patient personality traits on relationships with health care professionals and on adherence to medication regimensInt J Pharm Pract200210SupplR95

- BodenheimerTWagnerEHGrumbachKImproving primary care for patients with chronic illnessJAMA2002288141775177912365965

- NorrisSLEngelgauNMNarayanKMEffectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trialsDiabetes Care2001243531587

- DeakinTMcShaneCECadeJEWilliamsRDGroup based training for self-management strategies in people with type 2 diabetes mellitusCochrane Database Syst Rev20052CD00341715846663