Abstract

Hypertension treatment and control is largely unsatisfactory when guideline-defined blood pressure goal achievement and maintenance are considered. Patient- and physician-related factors leading to non-adherence interfere in this respect with the efficacy, tolerability, and convenient use of pharmacological treatment options. Blockers of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) are an important component of antihypertensive combination therapy. Thiazide-type diuretics are usually added to increase the blood pressure lowering efficacy. Fixed drug–drug combinations of both principles like candesartan/hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) are highly effective in lowering blood pressure while providing improved compliance, a good tolerability, and largely neutral metabolic profile. Comparative studies with losartan/HCTZ have consistently shown a higher clinical efficacy with the candesartan/HCTZ combination. Data on the reduction of cardiovascular endpoints with fixed dose combinations of antihypertensive drugs are however scarce, as are the data for candesartan/HCTZ. But many trials have tested candesartan versus a non-RAS blocking comparator based on a standard therapy including thiazide diuretics. The indications tested were heart failure and stroke and particular emphasis was put on elderly patients or those with diabetes. In patients with heart failure, for example, the fixed dose combination might be applied in patients in whom individual titration resulted in a dose of 32 mg candesartan and 25 mg HCTZ which can then be combined into one tablet to increase compliance with treatment. Also in patients with stroke the fixed dose combination might be used in patients in whom maintenance therapy with both components is considered. Taken together candesartan/HCTZ assist both physicians and patients in achieving long-term blood pressure goal achievement and maintenance.

Background

Hypertension is a highly prevalent risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, heart failure (HF), renal disease, and recurrent cardiovascular events. It has been shown to reduce the number of life-years lost and the number of years lived with disability by 64.3 million globally.Citation1 The European Society of Hypertension (ESH) classifies optimal blood pressure at <120 mmHg systolic blood pressure (SBP), and <80 mmHg diastolic blood pressure (DBP).Citation2

A therapeutic reduction of elevated blood pressure (BP) levels has been shown to decrease cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.Citation3 For the pharmacological management of hypertension, lowering BP below 140/90 mmHg in all patients is requested. Specific patients, those with diabetes mellitus or chronic kidney disease, need further BP reduction (<130/80 mmHg or <125/75 mmHg, respectively).

However these BP targets are difficult to meet despite the availability of a number of effective antihypertensive drugs. Consequently hypertension control is largely ineffective as the achievement of guideline defined treatment targets with about 20% of patients in Europe and up to 50% of patients in the US being finally controlled when treated.Citation4,Citation5 BP target achievement is even worse in patients with comorbid disease like diabetes mellitus.

Patient perspective

Hypertension is a rather unspectacular disease with unspecific symptoms that are, from a patient perspective, in many cases not perceived to occur in relation to hypertension. Patients therefore are reluctant to accept physicians’ recommendations to adopt life-style changes (weight reduction, reduction of sodium intake, and increased physical activity), which are the recommended first steps in the treatment of hypertension.

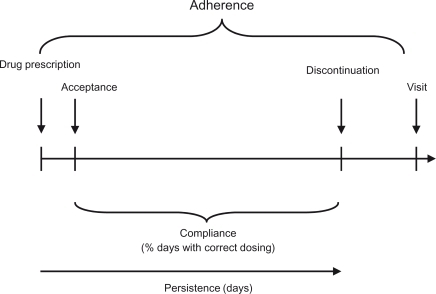

It becomes even more difficult to convince patients for the need of action when antihypertensive pharmacotherapy is introduced. A number of patient-related factors leading to nonadherence like frequent dosing,Citation6,Citation7 drug-related adverse events (AEs),Citation8 health beliefs,Citation9 drug–drug interactions and associated medical conditions interfere with the patients’ willingness to take drugs as prescribed. For an overview of terms used to describe adherence see . Actually approximately half of the patients on antihypertensive drug therapy discontinue therapy by the end of the first year.

Hence, from a patient perspective, there is a need for effective, highly tolerable and convenient medication that does not interfere with daily life while controlling hypertension-associated risk.

Physician perspective

Recent data suggest that also physicians’ attitudes and treatment strategies hamper the effectiveness of current therapy.Citation10–Citation12 In a recent global survey in a random sample of primary care physicians, 41% of physicians aimed to reduce BP to “acceptable levels” only, although generally agreeing with guideline recommended treatment goals. Physicians further believed that 62% of their patients had their BP controlled. However, in fact only 6% of patients with hypertension in the UK had their BP lowered to the recommended levels.Citation13 In France, Germany, Italy, and Spain only 13% of hypertensive patients have their BP controlled.Citation14

The physicians’ needs in the treatment of hypertension are partially overlapping with patients’ needs. However, in the face of low patient compliance, the chronic nature of the disease, and increasing budget constraints, a possible solution seems to be difficult to determine.

Treatment patterns

Globally about one-third of patients receive monotherapy, one-third dual combination therapy, and one-third 3 or more antihypertensive drugs. The NICE for example calculated that 36% of patients in the UK receive monotherapy, 38% dual combination therapy, and 26% 3 or more drug–drug combinations.Citation15 In a recent drug utilization analysis in primary care in Germany, 29.2% of treated patients received one, 43.7% received 2, and 27.2% received 3 or more antihypertensive drugs.Citation16

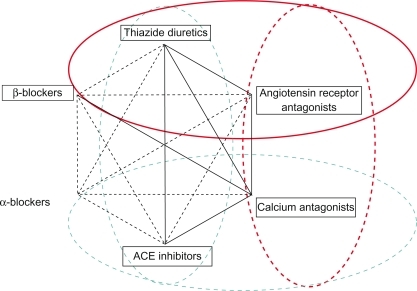

According to the aforementioned studyCitation16 40.8% of patients in Germany received ACE inhibitors (ACEi), 36.1% beta blockers, 31.7% diuretics, 22.3% calcium channel blockers (CCBs) and 14.1% angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).Citation16 Frequent drug–drug combinations were ACEi or ARBs in combination with diuretics, CCBs, and beta blockers which is mostly in accordance with recent guidelines in which 4 out of 6 recommended combinations are ACEi/ARB based.Citation17

Guidelines

The 2007 ESH/ESC guideline recognize 5 major antihypertensive drug classes – thiazide diuretics, CCBs, ACEi, ARBs, and betablockers – to be suitable for the initiation and maintenance of antihypertensive treatment.Citation17 The JNC VII guidelinesCitation18 on the other hand recommend using thiazide diuretics first. Both guidelines agree however in recommending the use of particular drug classes based on the presence of compelling indications.

ACEi and ARBs are recommended for the largest variety of compelling indications (for a detailed overview see ), with only minor compelling contraindications in patients with pregnancy, hyperkalemia, bilateral renal artery stenosis, and angioneurotic edema (ACEi only). Therefore both drug classes are used, as illustrated by data from different drug utilization studies,Citation16,Citation19 in 50% to 60% of patients.

Table 1 Compelling indications and contraindications in the use of antihypertensive drug classesCitation17

Drug–drug combination therapy

According to the ESH/ESC guidelines,Citation17 the following drug–drug combinations have been found to be effective and well tolerated in randomized efficacy trials: Thiazide diuretic plus ACEi, thiazide diuretic and ARB, CCB and ACEi, CCB and ARB, CCB and thiazide diuretic, and beta blocker and dihydropiridine CCBs. Thus, 4 out of 6 recommended dual antihypertensive combinations are ACEi/ARB based ().

Figure 2 Four out of 6 recommended dual antihypertensive combination therapies include blockers of the renin–angiotensin system.

Reproduced with permission from Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2007; 25(6):1105–1187.Citation17 Copyright © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

The ACCOMPLISH study triggered a lively discussion about the relative importance of drug–drug combinations.Citation20,Citation21 It was designed to test whether benazepril 40 mg combined with amlodipine 10 mg would result in stronger cardiovascular event reduction than benazepril 40 mg/HCTZ 25 mg. Inclusion and exclusion criteria favored the selection of patients with compelling indications for the use of CCBs. The composite primary endpoint of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality was reduced by 19.6% in patients receiving benazepril/amlodipine versus benazepril/HCTZ (9.6 versus 11.8%; hazard ratio [HR] 0.80, 95% CI 0.72–0.90). The secondary endpoint of death from cardiovascular causes, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and non-fatal stroke was reduced by 21% with a HR of 0.79 (95% CI 0.67–0.92). Side effects were generally however more frequent with amlodipine than with the thiazide diuretic. Unfortunately no similar comparative study of the ACCOMPLISH type exists for patients with compelling indications for thiazide diuretic use.Citation22 At present the evidence base is weak for deciding which patient would benefit the most from either combination.

Law and Wald have suggested combining ACEi/ARBs with a low dose of any of the other drug classes to maximize BP lowering efficacy while maintaining a placebo-like tolerability.Citation23 This recommendation was based on the metaanalytic observation that both ACEi and ARBs maintain a particular low AE profile in doses up to 4 times standard dose. On the contrary all other drug classes (CCBs, betablockers, thiazides) showed a steep incline of side effects at higher doses, while the tolerability was good at half-standard or even at standard dose.

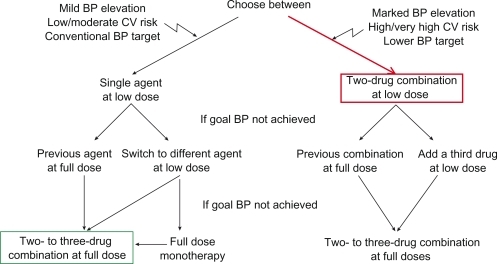

The common approach to control BP in hypertensive patients is to titrate monotherapy to full dose and to add another agent if BP is still high (, green). Drugs might be exchanged if there is indication of non-response to a particular agent. More recently the ESH/ESC guidelinesCitation17 introduced the concept of first-line combination therapy at low dose in patients with marked BP elevation, low target BPs, and high or very high cardiovascular risk (, red). This has been shown to be effective and safe and tolerability of first-line combination therapy is excellent.Citation24,Citation25

Figure 3 Combination therapy as an escalation option and as first-line therapy.

Reproduced with permission from Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2007; 25(6):1105–1187.Citation17 Copyright © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Requirements for antihypertensive drugs

In summary, from a patient, physician, and societal perspective there is a clear need for drug–drug combinations which provide effective BP lowering, and display a low side effect profile and a high adherence of both physicians and patients with treatment. This would enable BP control to be increased considerably and would in turn not only save on hypertension-related morbidity (stroke, ischemic heart disease) and mortality but also on costs.

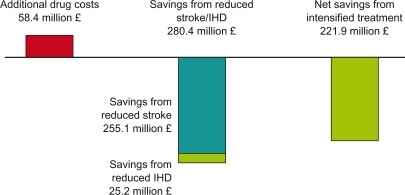

It has been calculated for the UK that achieving a systolic BP of 140 mmHg on a large scale would decrease stroke incidence by up to 44% depending on age group considered and ischemic heart disease incidence up to 35%.Citation15 Assuming that a reduction of stroke incidence of 9% and ischemic heart disease of 4% across age groups might actually be achievable, the annual saving to the NHS would be £255 million for stroke and £25 million for ischemic heart disease while investing £58 million into drugs (net benefit to the NHS £222 million) ().

Figure 4 Cost savings in the UK by intensifying antihypertensive drug treatment.Citation15

Candesartan/HCTZ

The fixed drug–drug combination of candesartan cilexetil in a dose up to 32 mg and HCTZ in a dose up to 25 mg fulfils most of the above-mentioned requirements for improving BP control and related morbidity on a larger scale.

Candesartan

Candesartan is an ARB that is administered orally as candesartan cilexetil; it is rapidly and completely converted to candesartan, the active compound, during absorption from the upper gastrointestinal tract.Citation26 It is characterized by a strong binding affinity to the angiotensin II type 1 receptor and its slow dissociation. Its binding to the AT1 receptor is insurmountable, meaning that it cannot be overcome by high concentrations of angiotensin II and, under physiological conditions, may even not dissociate until the AT1 receptor is recycled.Citation26

Twenty-four hours after administration to healthy volunteers, the angiotensin II inhibiting activity per milligram of candesartan was stronger than that shown by other ARBs.Citation27 The trough-to-peak ratio is almost 90% (mean of all doses available). After a missed dose of candesartan, losartan, or placebo, 48-hour post-dose significant reductions of BP have been observed with candesartan 16 mg daily but not with losartan or placebo.Citation28

Candesartan, applied as oral monotherapy, results in a strong dose-dependent reduction of both SBP and DBP between 4 and 16 mg, levelling off at 32 mg, and reaching its maximum at 8 weeks after treatment initiation.Citation29,Citation30 In a direct comparison of 16 mg candesartan and 20 mg enalapril candesartan was significantly more effective in reducing SBP and DBP (−13.5/−8.7 versus −9.9/−5.8 mmHg; P = 0.008).Citation31 It was also shown that BP returned to baseline after a missed dose of enalapril (−7.2/−4.5 mmHg) earlier than after a missed dose of candesartan (−11.4/−8.0 mmHg; P = 0.0002). Candesartan (up to 16 mg) and losartan (up to 50 mg) were compared in an 8-week study.Citation32 Candesartan reduced diastolic BP by 8.9 and 10.3 mmHg with the 8 and 16 mg doses, respectively, while the BP reduction with losartan 50 mg was 3.7 mmHg, the latter comparison reaching statistical significance (P = 0.013). Twenty-four hours after the ingestion of candesartan 100% of the peak SBP/DBP lowering effect was preserved (trough/peak ratio about 100% both systolic and diastolic) while only 70% of the losartan effect was preserved (trough/peak ratio 70% both systolic and diastolic).Citation32 These data were essentially confirmed by Lacourciere et al which also demonstrated, that after a missed dose of 16 mg candesartan, the effect was well preserved after 36 hours, while the effect of 100 mg losartan was significantly reduced.Citation28

It is tempting to speculate that differences in effectiveness of these ARBs may reflect pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic differences. The elimination half-life of candesartan is longer than that of losartan and its active metabolite. Candesartan cilexetil produces clear dose-dependent antihypertensive effects, whereas it has been difficult to demonstrate this property for losartan.Citation26,Citation32

Hydrochlorothiazide

HCTZ mainly acts within the lumen of the distal nephron, blocking the luminal transmembrane-coupled sodium chloride transport system. The mechanism by which thiazide diuretics reduce BP is however not completely understood. It has been proposed that during long-term therapy, thiazides act by reducing total peripheral resistance probably through a direct vascular effect.Citation33 It is important to note however that in vivo vasodilation was achieved at higher doses than those reached during long-term oral treatment.Citation34 HCTZ treatment in patients with hypertension induced changes in plasma volume, cardiac output, mean arterial pressure, stroke volume, heart rate, and total peripheral resistance.Citation33,Citation35

HCTZ has a half-life of 8 to 15 hours on chronic use and a duration of action that is slightly longer.Citation36 HCTZ 50 mg twice daily for 12 or 36 weeks, after a 4-week placebo run-in period, lowered mean arterial pressure in 13 patients with untreated essential hypertension and DBP > 100 mmHg.Citation35 Compared with the mean baseline value (177.2 mmHg), these reductions were significant throughout the study duration.

BP reduction with candesartan/HCTZ versus placebo

Fixed dose combinations of candesartan and HCTZ are available in various doses. Candesartan 32 mg once daily has to be regarded as a high dose (4 times standard dose).Citation23 HCTZ 12.5 and 25 mg have to be regarded as a half-standard and standard dose, respectively. Therefore the available combinations fulfil the requirements suggested by Law and WaldCitation23 for maximizing efficacy while maintaining a high tolerability.

The extent of BP reduction with candesartan/HCTZ depends on baseline BP and the dose used. A variety of combinations including 2, 4, 6, 8, 16, or 32 mg candesartan and 6.25, 12.5, or 25 mg HCTZ, respectively, has been tested in clinical trials versus respective monotherapies or placebo.Citation25,Citation37–Citation41 Uen et al for example demonstrated that replacing previously ineffective antihypertensive drugs by candesartan/HCTZ in patients with uncontrolled arterial hypertension significantly reduced both BP and ST-segment depression during daily life.Citation41 Taken together these studies have consistently shown that combinations of candesartan with HCTZ, administered orally once a day for 4 to 52 weeks, induced significant reductions in SBP and DBP from baseline in patients with mild, moderate, or severe hypertension.

In a recent study by Edes et al (baseline DBP 90–114 mmHg), mean reductions in SBP and DBP were significantly greater with candesartan 32/HCTZ 25 mg (21/14 mmHg) than with candesartan 32 mg alone (13/9 mmHg), HCTZ 25 mg alone (12/8 mmHg), or placebo (4/3 mmHg) (P < 0.001 for all comparisons).Citation39 The proportion of patients with controlled BP (SBP < 140 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg) at the end of this study was also significantly greater in the candesartan 32/HCTZ 25 mg group (63%) than in the other treatment groups (P < 0.001 for all comparisons).

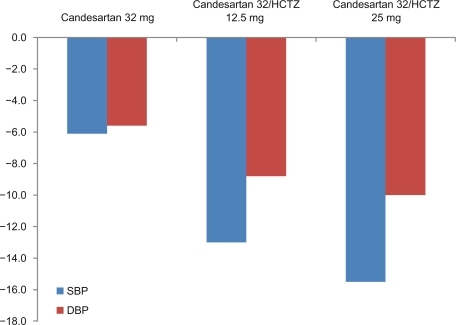

Bönner investigated the efficacy of candesartan 32 mg in combination with HCTZ 12.5 or 25 mg in patients not optimally controlled using candesartan monotherapy.Citation42 A total of 3521 patients with treated or untreated hypertension and sitting DBP of 90 to 114 mmHg were included. After a single blind run-in phase (2 weeks candesartan 16 mg followed by a 6-week treatment with candesartan 32 mg) 1975 patients who still had DBP readings of 90 to 114 mmHg were randomized to an 8-week double-blind treatment with either candesartan 32 mg alone or in combination with HCTZ 12.5 mg or 25 mg respectively. Mean BP (153/97 mmHg at baseline) was further reduced during the double-blind treatment phase by 6.1/5.6 mmHg in the candesartan monotherapy group, by 13.0/8.8 mmHg in the fixed combination with HCTZ 12.5 mg group, and by 15.5/10.0 mmHg in the fixed combination with HCTZ 25 mg group (P < 0.01 for all between treatment comparisons) ().

Figure 5 Blood pressure reduction with 32 mg candesartan alone or in combination with 12.5 or 25 mg HCTZ in patients not sufficiently controlled on monotherapy.Citation42

Bönner et al tested the first-line use of candesartan 16 mg/HCTZ 12.5 mg in 166 patients with no prior pharmacotherapy for a treatment duration of 6 weeks.Citation25 Blood pressure was reduced by 38.1/29.4 mmHg with 40% of patients achieving a normalization of BP. Tolerability was good showing that first line combination therapy is feasible and safe.

BP reduction with candesartan/HCTZ versus losartan/HCTZ

Ohma et al compared fixed dose combinations of candesartan 16/HCTZ 12.5 mg and losartan 50/HCTZ 12.5 mg in patients insufficiently controlled on previous monotherapy.Citation43 BP at randomization was 159.5/98.4 mmHg and 160.5/98.5 mmHg, respectively. After 12 weeks there was a greater reduction of BP with candesartan/HCTZ (−19.4/−10.4) than with losartan/HCTZ (−13.7/−7.8 mmHg), the differences being statistically significant. Twelve patients withdrew in the candesartan/HCTZ group (8 due to AEs), and 17 in the losartan/HCTZ group (12 AEs).

König compared candesartan/HCTZ and losartan/HCTZ in a 6-week study.Citation44 Twenty-four-hour postdose mean seated BP was reduced by 32.2/21.1 mmHg (systolic/diastolic) in the candesartan/HCTZ group and 23.8/14.9 mmHg in the losartan/HCTZ group (P < 0.001). Blood pressure reductions 48 hours postdose were 25.6/16.4 mmHg for candesartan/HCTZ and 9.2/4.2 mmHg for losartan/HCTZ, with differences between treatments being highly significant in favor of candesartan/HCTZ (16.5/12.2 mmHg; P < 0.001). Both treatments were well tolerated.

Tolerability/compliance

ARBs are generally regarded to be a drug class with high compliance/persistence.Citation45 Persistence with antihypertensive medication (including candesartan) was compared between different drug classes and between substances within one drug class in an Australian analysis covering the years 2004 to 2006.Citation46 The database yielded information relating to 48,690 patients prescribed antihypertensive medication. The median persistence time was 20 months, which was also the median persistence with ARBs or ACEi. The median persistence with CCBs was considerably lower (median persistence time 7 months; −57%, P< 0.001). There were further differences in persistence between individual drugs in the respective classes, the best outcomes being with candesartan and telmisartan (10%–20% better than the other ARBs considered), perindopril (ACEi; 25% better other ACEi) and lercanidipine (CCB; 25% better than other CCBs). This high persistence was reflected in the recent DIRECT trial in that about 80% of patients were compliant with 32 mg candesartan even when being nominally normotensive.Citation47,Citation48

Candesartan/HCTZ is generally well tolerated in patients with mild to moderate hypertension. Combined data from 5 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials indicated that AEs during candesartan/HCTZ therapy (up to 16 mg/25 mg once daily) are uncommon and only few were serious.Citation49 Among patients receiving candesartan/HCTZ or placebo the incidence of serious AEs was 1.6 and 2.1%, respectively, while 3.3 and 2.7% of patients discontinued treatment because of AEs. The most common AEs were headache, back pain, dizziness, and respiratory infections.

Recent trials indicated that the AE profile of candesartan 32 mg in combination with 12.5 or 25 mg HCTZ is comparable to the aforementioned observations.Citation39,Citation42 Bönner et al reported about 1% serious AEs that were independent of whether monotherapy with candesartan or combination therapy including HCTZ was considered. For metabolic parameters, a slight increase of serum ureate and serum creatinine was observed with the fixed combinations while other parameters were essentially unchanged ().Citation42 Edes et al reported a rate of serious AE for the fixed dose combination that was even lower compared to placebo (0.2% versus 3.1%), with overall AE rate ranging between 23% and 25% for placebo, HCTZ, candesartan, and their combination.Citation39

Table 2 Laboratory values at baseline, and mean change (±SD) from baselineTable Footnotea after 8 weeks of treatmentCitation42

Mengden et al compared drug regimen compliance (DRC) with antihypertensive combination therapy in patients whose BP was controlled versus uncontrolled after 4 weeks of self-monitored BP measurement.Citation50 Whether switching one drug of the combination therapy to candesartan/HCTZ (16 mg/12.5 mg) in uncontrolled patients with and without compliance intervention program would improve BP normalization was also evaluated. It was found that normalization of BP was associated with superior drug regimen compliance in previously uncontrolled patients treated with a combination drug regimen. Switching still-uncontrolled patients to candesartan/HCTZ significantly improved BP control and stabilized a declining DRC.

Patient types

Patients with heart failure

Heart failure is a frequent comorbidity in patients with hypertension. It is characterized by a decline in systolic or diastolic function, the latter being a typical complication of long-term uncontrolled hypertension. The fixed dose combination of candesartan/HCTZ has never been formally tested in this patient population, but the benefits of blocking the RAS and enhancing diuresis are basic concepts in the treatment of HF.Citation51 HCTZ is recommended for the treatment of patients with HF in doses of 25 mg to initiate treatment and maintenance doses of between 2.5 and 100 mg daily.Citation51 Candesartan is recommended to be started at a dose of 4 or 8 mg daily and uptitrated to a target dose of 32 mg.

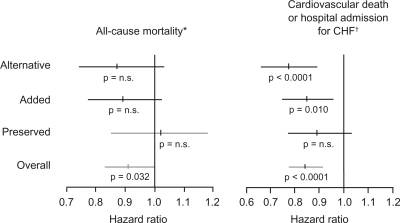

The basis for the recommendation of candesartan was the results of the CHARM trial program.Citation52 In CHARM candesartan was tested in patients with systolic HF given either on top of an ACEiCitation53 or in cases of ACEi intolerance.Citation54 A third trial investigated the effect of candesartan in diastolic HF (HF with preserved systolic function).Citation55 Overall, 7601 patients were randomly assigned candesartan (titrated to 32 mg once daily) or matching placebo, and followed up for at least 2 years. In the overall CHARM trial program 82.8% of patients in the candesartan arm and 82.6% of patients in the placebo arm received diuretics and a further 16.9 and 16.6% respectively spironolactone.

In CHARM Alternative (candesartan given instead of an ACEi) treatment resulted in a relative risk reduction (RRR) of death from cardiovascular cause or hospital admission for worsening HF of 23% (ARR 7%, NNT 14, over 34 months of follow-up, adjusted P < 0.0001 ().Citation54 In the CHARM Added trial (candesartan on top of existing ACEi therapy) candesartan cotreatment resulted in a 15% RRR of cardiovascular death or hospital admission for CHF (ARR 4%, NNT 25, over 41 months of follow-up, adjusted P = 0.010).Citation54 The CHARM Preserved trial (candesartan in patients with HF but preserved systolic function) candesartan did not show a significant reduction in the risk of the primary composite endpoint (adjudicated death from cardiovascular causes or admission with HF) but did show a significant reduction in the number of patients admitted to hospital with CHF (ARR 3.3%, NNT 30, over 37 months follow up, P = 0.017).Citation55

Figure 6 Results of the CHARM trial program.Citation52–Citation55

Reprinted from Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, et al. Effects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programme. The Lancet. 362:759–766.Citation52 Copyright © 2003, with permission from Elsevier.

In summary it appears possible to initiate drug treatment of HF with both combination agents at low dose, uptitrate candesartan and HCTZ as warranted and, should the doses fit, switch to a fixed dose combination of candesartan 32/HCTZ 25 mg for maintenance treatment.

Patients with stroke

Stroke is a frequent, serious, and finally costly complication of hypertension. Candesartan was tested in 2 trials with respect to this indication, one testing the capability of preventing stroke or related disabilities (SCOPE,Citation56 see section Elderly patients), the other testing cerebro- and cardiovascular endpoints in patients with a history of stroke (ACCESS).Citation57

ACCESS was designed to evaluate the safety of early antihypertensive treatment in patients with acute cerebral ischemia).Citation57 Patients with motor paresis and initial SBP > 200 mmHg and/or DBP > 110 mmHg or mean BP of 2 measurements > 180 mmHg and/or 105 mmHg, respectively, were included. The trial was stopped prematurely after the recruitment of 349 patients due to an imbalance in endpoints. Cumulative 12-month mortality and the number of vascular events differed significantly in favor of the candesartan group (OR 0.475; 95% CI 0.252–0.895). There were no cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events as a result of hypotension. Treatment was started with 4 mg candesartan daily on day 1. On day 2, dosage was increased to 8 or 16 mg candesartan if BP exceeded 160 mmHg systolic or 100 mmHg diastolic. In patients in the candesartan group who were still hypertensive on day 7 (mean daytime BP > 135/85 mmHg), candesartan was increased or an additional antihypertensive drug (HCTZ, felodipine, metoprolol) was added. The control group received placebo for the first 7 days and 8 to 16 mg candesartan throughout the rest of the study.

In the ongoing SCAST trial (NCT00120003) candesartan is tested in patients with stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) and SBP ≥ 140 mmHg. Patients receive 4 mg candesartan on day 1; 8 mg on day 2; 16 mg on days 3 to 7. Dose adjustment in cases of SBP < 120 mmHg, or symptomatic fall in BP are mandated. From day 8 therapies can be supplemented with any antihypertensive agent including diuretics.

Taken together there is good evidence that early candesartan treatment after acute stroke might be able to prevent vascular events and mortality. The fixed dose combination might be useful after several days of candesartan mono-therapy uptitration after which HCTZ in low dose is added to maintain or achieve BP control.

Patients with diabetes mellitus

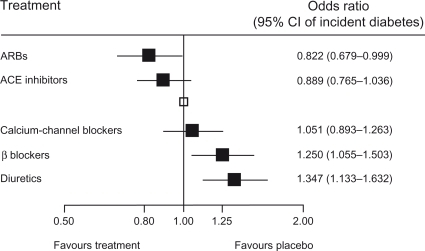

Antihypertensive treatment in diabetic patients is complicated by the fact that baseline BP readings are usually high, while having to meet lower BP goals (<130/80 mmHg in most cases).Citation17 ARBs are beneficial within the context of diabetes because they have been shown to delay the development of diabetes more than any other drug class ()Citation58,Citation59 and to be at least neutral or even beneficial with respect to metabolic parameters. As has been shown in a number of clinical trials, the reduction of cardiovascular morbidity following antihypertensive treatment is usually, but not always, pronounced in patients with diabetes.Citation60,Citation61

Figure 7 Development of diabetes – results of a meta-analysis.

Reprinted from Lam SK, Owen A. Incident diabetes in clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs. The Lancet. 369:1513–1514.Citation59 Copyright © 2007, with permission from Elsevier.

Candesartan reduced the number of patients developing diabetes in the CHARM,Citation62 SCOPE,Citation63 and ALPINE trials.Citation64 When administered to a group of hypertensive subjects it reduced C-reactive protein and increased adiponectin and markers of insulin sensitivity, as measured by QUICKI (Quantitative Insulin-Sensitivity Check Index).Citation65

It also reduced BP effectively in diabetic patients.Citation66 Bramlage et al demonstrated in an observational study in primary care that candesartan 16/HCTZ 12.5 mg lowered BP effectively in patients with and without diabetes.Citation45 The absolute amount of BP lowering (−27.2/−1–3.4 mmHg) appeared to be dependent on baseline BP but did not differ among patient types (diabetes, metabolic syndrome, or neither condition).

Microalbuminuria in diabetes is strongly predictive of nephropathy, end-stage renal disease, and premature cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Effective preventive therapies are therefore a clinical priority. The effect of candesartan in the prevention of microalbuminuria was tested in a pooled analysis of the DIRECT trial program in which normotensive patients with type 1 (n = 3326) and 2 (n = 1905) diabetes were included.Citation67 Due to the study design the incidence of microalbuminuria was low in this analysis and no differences in the risk for albuminuria were noted (HR 0.95; 95% CI 0.78–1.16). Pooled results showed that the annual rate of change in albuminuria was 5.53% lower (CI, 0.73%–10.14%; P = 0.024) with candesartan than with placebo. Studies conducted by TrenkwalderCitation68 and MogensenCitation69 have however shown that candesartan is effective in lowering the level of albumin excretion in patients with hypertension, diabetes, and already existing microalbuminuria. Taking a much higher than recommended dose of the hypertension drug candesartan was shown to effectively lower the amount of protein excreted in the urine of patients with kidney disease in a study by Burgess et al.Citation70 269 patients with persistent proteinuria despite treatment with 16 mg candesartan were randomized to receive 16, 64, or 128 mg daily of candesartan for 30 weeks. It was found that patients taking 128 mg of candesartan experienced a 33% reduction in proteinuria compared with those receiving 16 mg candesartan by the end of the study. There is however a missing link between microalbuminuria reduction and morbidity and mortality endpoints which have so far been reported only from post-hoc analyses. A respective study is however already underway to provide this link.Citation71 Important in this respect are the results of the GUARD study that combined an ACEi with either amlodipine or HCTZ and demonstrated that with HCTZ the nephroprotective effect of benazepril was preserved while it was reduced when amlodipine was chosen as the combination partner.Citation72

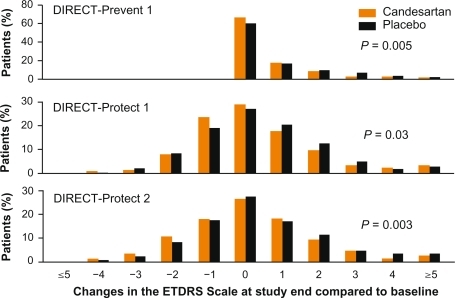

The DIRECT trial program was a series of clinical trials investigating the effect of candesartan on the development and progression diabetic retinopathy who were either normotensive or had treated hypertension.Citation47,Citation73 DIRECT consisted of three randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled multicenter studies designed to investigate the potential for candesartan in halting the progression of, and possibly prevent, diabetic retinopathy. Results showed that candesartan was beneficial for patients with type 2 diabetes who had established mild to moderate retinopathy, because candesartan had an additional, BP-independent effect on improvement of retinopathy (). Candesartan was also shown to be indicated for patients with type 1 diabetes without retinopathy, in order to reduce their risk of developing retinopathy.

Figure 8 Results of the DIRECT trial program.Citation47,Citation73

In summary there is an abundance of evidence for the use of candesartan in patients with diabetes or a high risk for developing such. Data on the use of a fixed dose combination of candesartan/HCTZ are scarce, leaving it unproven that a combination treatment is likewise beneficial. Data addressing the dysmetabolic potential have however shown that the metabolic profile of HCTZ is neutralized when adding candesartan. Because of the need for multiple drug–drug combinations there is a clear need for combination therapy including diuretics, which are favored in common co-morbidities of diabetes, eg, CHF or diabetic nephropathy.

Elderly patients

The pharmacokinetics of candesartan were investigated after single and repeated once-daily doses in a trial by Hübner et alCitation74 of candesartan in the dose range 2 to 16 mg in both younger (19–40 years) and elderly (65–78 years) healthy volunteers. The area under the curve (AUC) and maximal concentration (Cmax) of candesartan showed dose-proportional increases in the dose range of 2 to 16 mg candesartan after both single and repeated once-daily tablet intake, indicating linear pharmacokinetics in both younger and elderly healthy subjects. The time to peak candesartan concentrations after tablet intake was consistently approximately 4 hour at all dose levels. Only mild AEs were recorded, with ‘headache’ the most commonly reported event, and no increase in the number of reported AEs was observed with higher doses of candesartan cilexetil.Citation74

Results of the SCOPE study implied that candesartan treatment reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in old and very old patients with mild to moderate hypertension.Citation75,Citation76 Candesartan-based antihypertensive treatment may also have positive effects on cognitive function and quality of life. SCOPE was a multi-center, prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. The primary objective was to assess the effect of candesartan 8–16 mg once daily, on major cardiovascular events in elderly patients (70–89 years of age) with mild hypertension (DBP 90–99 and/or SBP 160–179 mmHg). The main analysis showed that non-fatal stroke was reduced by 28% (P = 0.04) in the candesartan group compared with the control group, and there was a non-significant 11% reduction in the primary endpoint, major cardiovascular events (P = 0.19). Significant risk reductions with candesartan in major cardiovascular events (32%, P = 0.013), cardiovascular mortality (29%, P = 0.049) and total mortality (27%, P = 0.018) were observed in patients who did not receive add-on therapy after randomization, and in whom the difference in BP was 4.7/2.6 mmHg. Other analyzes suggest positive effects of candesartan-based treatment on cognitive function, quality of life and new-onset diabetes. Results of SCOPE strongly suggested that candesartan treatment reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in old and very old patients with mild to moderate hypertension. Candesartan-based antihypertensive treatment may also have positive effects on cognitive function and quality of life.Citation76

Subgroup analyses from the CHARM study in patients with HF showed that older patients were at a greater absolute risk of adverse CV mortality and morbidity outcomes, but derived a similar RRR and, therefore, a greater absolute benefit from treatment with candesartan, despite receiving a somewhat lower mean daily dose of candesartan.Citation77 Adverse effects were more common with candesartan than with placebo, although the relative risk of adverse effects was similar across age groups. The benefit to risk ratio for candesartan was thus favorable across all age groups.

In summary, given that diuretics are frequently indicated in elderly patients there appears to be a role for fixed dose combinations of candesartan/HCTZ. But again evidence has been acquired with free combinations of candesartan with other antihypertensive drugs including thiazide diuretics.

Economic evaluation

The addition of candesartan to standard therapy for CHF provided important clinical benefits at little or no additional cost in France, Germany, and the UK, according to a detailed economic analysis focusing on major cardiovascular events and prospectively collected resource-use data from the CHARMAdded and CHARM-Alternative trials in patients with CHF and left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction.Citation78 Results of a corresponding cost-effectiveness analysis showed that candesartan was either dominant over placebo or was associated with small incremental costs per life-year gained, depending on the country and whether individual trial or pooled data were used. Preliminary data from a US cost-effectiveness analysis based on CHARM data also showed favorable results for candesartan cilexetil. Two cost-effectiveness analyses of candesartan cilexetil in hypertension have been published, both conducted in Sweden.

Data from the SCOPE trial in elderly patients with hypertension, which showed a significant reduction in non-fatal stroke with candesartan-based therapy versus non-candesartan based treatment, were incorporated into a Markov model and an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of 12,824 per QALY gained was calculated (2001 value).

In conclusion, despite some inherent limitations, economic analyses incorporating CHARM data and conducted primarily in Europe have shown that candesartan cilexetil appears to be cost-effective when added to standard CHF treatment in patients with CHF and compromised LV systolic function. The use of candesartan cilexetil as part of antihypertensive therapy in elderly patients with elevated BP was also deemed to be cost effective in a Swedish analysis, primarily resulting from a reduced risk of non-fatal stroke (as shown in the SCOPE study); however, the generalizability of results to other contexts has not been established. Cost-effectiveness analyses comparing candesartan cilexetil with ACE inhibitors or other angiotensin receptor blockers in CHF or hypertension are lacking, and results reported for candesartan cilexetil in a Swedish economic analysis of ALPINE data focusing on outcomes for diabetes require confirmation and extension.

Conclusions

The fixed dose combination of candesartan and HCTZ is a valuable addition to the armamentarium of drugs in the treatment of hypertension, because of its high efficacy in reducing BP, its tolerability, and the high compliance of patients with treatment. Comparative studies with losartan/HCTZ have consistently shown a higher clinical efficacy with the candesartan/HCTZ combination. Candesartan/HCTZ therefore assists both physicians and patients in achieving long-term treatment goals.

Data on the reduction of cardiovascular endpoints with fixed dose combinations of antihypertensive drugs are scarce, as are the data for candesartan/HCTZ. However many trials have tested candesartan versus a non-RAS blocking comparator based on a standard therapy including thiazide diuretics. The indications tested were HF and stroke, and particular emphasis was put on elderly patients or those with diabetes. In patients with HF, for example, the fixed dose combination might be applied in patients in whom individual titration resulted in a dose of 32 mg candesartan and 25 mg HCTZ which can then be combined into one tablet to increase compliance with treatment. Also in patients with stroke the fixed dose combination might be used in patients in whom maintenance therapy with both components is considered.

Abbreviations

| ACCESS | = | The Acute Candesartan Cilexetil Therapy in Stroke Survivors; |

| ACCOMPLISH | = | Avoiding Cardiovascular Events in Combination Therapy in Patients Living with Systolic Hypertension; |

| ACEi | = | ACE inhibitor; |

| AE | = | adverse event; |

| ALPINE | = | Antihypertensive treatment and Lipid Profile In a North of Sweden Efficacy Evaluation; |

| ARB | = | angiotensin receptor blocker; |

| ARR | = | absolute risk reduction; |

| AT | = | angiotensin; |

| AUC | = | area under the curve; |

| BP | = | blood pressure; |

| CANDIA | = | CANdesartan and DIuretic vs Amlodipine in hypertensive patients; |

| CCB | = | calcium channel blocker; |

| CHARM | = | Candesartan in Heart Failure-Assessment of Reduction in mortality and Morbidity; |

| CHD | = | coronary heart disease; |

| CHF | = | chronic heart failure; |

| CI | = | confidence interval; |

| CV | = | cardiovascular; |

| DBP | = | diastolic blood pressure; |

| DDD | = | defined daily doses; |

| DIRECT | = | The DIabetic REtinopathy Candesartan Trials; |

| DRC | = | drug regimen compliance; |

| ESC | = | European Society of Cardiology; |

| ESH | = | European Society of Hypertension; |

| HCTZ | = | hydrochlorothiazide; |

| HDL | = | high-density lipoprotein; |

| HF | = | heart failure; |

| HR | = | hazard ratio; |

| JNC | = | Joint National Committee; |

| LIFE | = | Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension; |

| LV | = | left ventricular; |

| MOSES | = | Morbidity and Mortality after Stroke – Eprosartan vs Nitrendipine for Secondary Prevention; |

| NHS | = | National Health Service (UK); |

| NICE | = | National Institutes of Clinical Excellence; |

| NNT | = | number needed to treat; |

| OR | = | odds ratio; |

| QUICKI | = | Quantitative Insulin-Sensitivity Check Index; |

| PRA | = | plasma renin activity; |

| QALY | = | quality adjusted life year; |

| RAS | = | renin–angiotensin system; |

| RRR | = | relative risk reduction; |

| SBP | = | diastolic blood pressure; |

| SCAST | = | Scandinavian Candesartan Acute Stroke Trial; |

| SCOPE | = | Study on COgnition and Prognosis in the Elderly; |

| UK | = | United Kingdom; |

| US | = | United States. |

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this manuscript has been financially supported by Takeda Pharma, Aachen, Germany. Takeda had no role in outlining, editing or determining the final content of this review. This was left at the discretion of the authors who take full responsibility for its content.

Disclosures

TM, SU and PB disclose receipt of lecture honoraries and research support from Takeda Pharma, Aachen, Germany.

References

- WHO 20022009

- ManciaGDeBGDominiczakAGuidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Eur Heart J200728121462153617562668

- LewingtonSClarkeRQizilbashNPetoRCollinsRAge-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studiesLancet200236093491903191312493255

- KearneyPMWheltonMReynoldsKMuntnerPWheltonPKHeJGlobal burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide dataLancet2005365945521722315652604

- Wolf-MaierKCooperRSKramerHHypertension treatment and control in five European countries, Canada, and the United StatesHypertension2004431101714638619

- EisenSAMillerDKWoodwardRSSpitznagelEPrzybeckTRThe effect of prescribed daily dose frequency on patient medication complianceArch Intern Med19901509188118842102668

- LeenenFHWilsonTWBolliPPatterns of compliance with once versus twice daily antihypertensive drug therapy in primary care: a randomized clinical trial using electronic monitoringCan J Cardiol199713109149209374947

- FinckeBGMillerDRSpiroAIIIThe interaction of patient perception of overmedication with drug compliance and side effectsJ Gen Intern Med19981331821859541375

- MillerNHHillMKottkeTOckeneISThe multilevel compliance challenge: recommendations for a call to action. A statement for healthcare professionalsCirculation1997954108510909054774

- BerlowitzDRAshASHickeyECInadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive populationN Engl J Med199833927195719639869666

- OliveriaSALapuertaPMcCarthyBDL’ItalienGJBerlowitzDRAschSMPhysician-related barriers to the effective management of uncontrolled hypertensionArch Intern Med2002162441342011863473

- HymanDJPavlikVNSelf-reported hypertension treatment practices among primary care physicians: blood pressure thresholds, drug choices, and the role of guidelines and evidence-based medicineArch Intern Med2000160152281228610927724

- AldermanMWorld Health Organization– International Society of Hypertension Guideliines for the Management of HypertensionBealAKBlood Press19998Suppl 1943

- JuliusSWorldwide trends and shortcomings in the treatment of hypertensionAm J Hypertens2000135 Pt 257S61S10830790

- NICE costing reportURL: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG034costingreport.pdf 2002

- PittrowDKirchWBramlagePPatterns of antihypertensive drug utilization in primary careEur J Clin Pharmacol200460213514215042351

- ManciaGDe BackerGDominiczakAGuidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)J Hypertens20072561105118717563527

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRThe Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 ReportJAMA2003289192560257112748199

- StolkPVan WijkBLLeufkensHGHeerdinkERBetween-country variation in the utilization of antihypertensive agents: guidelines and clinical practiceJ Hum Hypertens2006201291792216988753

- JamersonKWeberMABakrisGLBenazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patientsN Engl J Med2008359232417242819052124

- JamersonKABakrisGLWunCCRationale and design of the avoiding cardiovascular events through combination therapy in patients living with systolic hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial: the first randomized controlled trial to compare the clinical outcome effects of first-line combination therapies in hypertensionAm J Hypertens200417979380115363822

- BramlagePFixed-dose combinations of renin-angiotensin blocking agents with calcium channel blockers or hydrochlorothiazide in the treatment of hypertensionExp Opin Pharmacother2009101117551767

- LawMRWaldNJMorrisJKJordanREValue of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trialsBMJ2003326740414271431

- FranklinSSNeutelJMDonovanMBouzamondoHIrbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide as initial therapy: subanalysis in patients with systolic BP > 180 mmHg and diastolic BP > 110 mmHg, efficacy and safetyJ Hypertens2008Suppl 1S159

- BönnerGFuchsWFixed combination of candesartan with hydrochlorothiazide in patients with severe primary hypertensionCurr Med Res Opin200420559760215140325

- OparilSNewly emerging pharmacologic differences in angiotensin II receptor blockersAm J Hypertens2000131 Pt 218S24S10678284

- FuchsBBreithaupt-GroglerKBelzGGComparative pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of candesartan and losartan in manJ Pharm Pharmacol20005291075108311045887

- LacourciereYAsmarRA comparison of the efficacy and duration of action of candesartan cilexetil and losartan as assessed by clinic and ambulatory blood pressure after a missed dose, in truly hypertensive patients: a placebo-controlled, forced titration study. Candesartan/Losartan study investigatorsAm J Hypertens19991212 Pt121181118710075377

- SeverPMichelJVoetBCandesartan cilexitil (CC): A meta-analysis of time-to-effect relationshipAm J Hypertens1998114 Pt 279A

- ElmfeldtDOlofssonBMeredithPThe relationships between dose and antihypertensive effect of four AT1-receptor blockers. Differences in potency and efficacyBlood Press200211529330112458652

- HimmelmannAKeinanen-KiukaanniemiSWesterARedonJAsmarRHednerTThe effect duration of candesartan cilexetil once daily, in comparison with enalapril once daily, in patients with mild to moderate hypertensionBlood Press2001101435111332334

- AnderssonOKNeldamSA comparison of the antihypertensive effects of candesartan cilexetil and losartan in patients with mild to moderate hypertensionJ Hum Hypertens199711Suppl 2S63S649331011

- ConwayJLauwersPHemodynamic and hypotensive effects of longterm therapy with chlorothiazideCirculation196021212713811661

- PickkersPHughesADRusselFGThienTSmitsPThiazide-induced vasodilation in humans is mediated by potassium channel activationHypertension1998326107110769856976

- van BrummelenPMan int VeldAJSchalekampMAHemodynamic changes during long-term thiazide treatment of essential hypertension in responders and nonrespondersClin Pharmacol Ther19802733283366987024

- CarterBLErnstMECohenJDHydrochlorothiazide versus chlorthalidone: evidence supporting their interchangeabilityHypertension20044314914638621

- AziziMNisse-DurgeatSFrench Collaborative GroupComparison of the antihypertensive effects of the candesartan 8 mg hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg combination vs the valsartan 80 mg hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg combination in patients with essential hypertension resistant to monotherapy. [abstract no. P2.367]J Hypertens200422Suppl 2S254S255

- OparilSMichelsonELLong term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of candesartan cilexitil added to hydrochlorothiazide in patients with severe hypertensionAm J Hypertens200912120

- EdesICombination therapy with candesartan cilexetil 32 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg provides the full additive antihypertensive effect of the components: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study in primary careClin Drug Investig2009295293304

- BramlagePSchonrockEOdojPWolfWPFunkenCImportance of a fixed combination of AT1-receptor blockade and hydrochlorothiazide for blood pressure lowering in cardiac risk patients. A postmarketing surveillance study with Candesartan/HCTZMMW Fortschritte der Medizin2008149Suppl 417218118402243

- UenSUnIFimmersRVetterHMengdenTEffect of candesartan cilexetil with hydrochlorothiazide on blood pressure and ST-segment depression in patients with arterial hypertensionDeutsche medizinische Wochenschrift (1946)20071323818617219340

- BönnerGAntihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of candesartan-hydrochlorothiazide 32/12.5 mg and 32/25 mg in patients not optimally controlled with candesartan monotherapyBlood Press200817Suppl 22230

- OhmaKPMilonHValnesKEfficacy and tolerability of a combination tablet of candesartan cilexetil and hydrochlorothiazide in insufficiently controlled primary hypertension – comparison with a combination of losartan and hydrochlorothiazideBlood Press20009421422011055474

- KönigWComparison of the efficacy and tolerability of combination tablets containing candesartan cilexetil and hydrochlorothiazide or losartan and hydrochlorothiazide in patients with moderate to severe hypertension: Results of the CARLOS-StudyClin Drug Invest2000194239246

- BramlagePHasfordJBlood pressure reduction, persistence and costs in the evaluation of antihypertensive drug treatment–a reviewCardiovasc Diabetol200981819327149

- SimonsLAOrtizMCalcinoGPersistence with antihypertensive medication: Australia-wide experience, 2004–2006Med J Aust2008188422422718279129

- SjolieAKKleinRPortaMEffect of candesartan on progression and regression of retinopathy in type 2 diabetes (DIRECT-Protect 2): a randomised placebo-controlled trialLancet200837296471385139318823658

- ChaturvediNPortaMKleinREffect of candesartan on prevention (DIRECT-Prevent 1) and progression (DIRECT-Protect 1) of retinopathy in type 1 diabetes: randomised, placebo-controlled trialsLancet200837296471394140218823656

- BelcherGLundeHElmfeldtDThe combination tablet of candesartan cilexetil 16 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg has a tolerability profile similar to that of placebo [abstract]J Hypertens200018Suppl 2S94

- MengdenTVetterHToussetEUenSManagement of patients with uncontrolled arterial hypertension – the role of electronic compliance monitoring, 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and Candesartan/HCTZBMC Cardiovasc Disord200663616942618

- DicksteinKCohen-SolalAFilippatosGESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM)Eur Heart J200829192388244218799522

- PfefferMASwedbergKGrangerCBEffects of candesartan on mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure: the CHARM-Overall programmeLancet2003362938675976613678868

- McMurrayJJOstergrenJSwedbergKEffects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Added trialLancet2003362938676777113678869

- GrangerCBMcMurrayJJYusufSEffects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trialLancet2003362938677277613678870

- YusufSPfefferMASwedbergKEffects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved TrialLancet2003362938677778113678871

- LithellHHanssonLSkoogIThe Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE): principal results of a randomized double-blind intervention trialJ Hypertens200321587588612714861

- SchraderJLüdersSKulschewskiAThe ACCESS Study: evaluation of Acute Candesartan Cilexetil Therapy in Stroke SurvivorsStroke20033471699170312817109

- ElliottWJMeyerPMIncident diabetes in clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs: a network meta-analysisLancet2007369955720120717240286

- LamSKOwenAIncident diabetes in clinical trials of antihypertensive drugsLancet200736995721513151417482972

- LindholmLHIbsenHDahlofBCardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with diabetes in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenololLancet200235993111004101011937179

- MacDonaldMRPetrieMCVaryaniFImpact of diabetes on outcomes in patients with low and preserved ejection fraction heart failure: an analysis of the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) programmeEur Heart J200829111377138518413309

- YusufSOstergrenJBGersteinHCEffects of candesartan on the development of a new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in patients with heart failureCirculation20051121485315983242

- ZanchettiAElmfeldtDFindings and implications of the Study on COgnition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE) – a reviewBlood Press2006152717916754269

- LindholmLHPerssonMAlaupovicPCarlbergBSvenssonASamuelssonOMetabolic outcome during 1 year in newly detected hypertensives: results of the Antihypertensive Treatment and Lipid Profile in a North of Sweden Efficacy Evaluation (ALPINE study)J Hypertens20032181563157412872052

- KohKKQuonMJHanSHChungWJLeeYShinEKAntiinflammatory and metabolic effects of candesartan in hypertensive patientsInt J Cardiol200610819610016246439

- DerosaGCiceroAFCiccarelliLFogariRA randomized, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group comparison of perindopril and candesartan in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitusClin Ther20032572006202112946547

- BilousRChaturvediNSjolieAKEffect of candesartan on microalbuminuria and albumin excretion rate in diabetes: three randomized trialsAnn Intern Med20091511112019451554

- TrenkwalderPLehtovirtaMDahlKLong-term treatment with candesartan cilexetil does not affect glucose homeostasis or serum lipid profile in mild hypertensives with type II diabetesJ Hum Hypertens199711Suppl 2S81S839331016

- MogensenCENeldamSTikkanenIRandomised controlled trial of dual blockade of renin-angiotensin system in patients with hypertension, microalbuminuria, and non-insulin dependent diabetes: the candesartan and lisinopril microalbuminuria (CALM) studyBMJ200032172741440144411110735

- BurgessEMuirheadNRene deCPChiuAPichetteVTobeSSupramaximal dose of candesartan in proteinuric renal diseaseJ Am Soc Nephrol200920489390019211712

- HallerHVibertiGCMimranAPreventing microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes: rationale and design of the Randomised Olmesartan and Diabetes Microalbuminuria Prevention (ROADMAP) studyJ Hypertens200624240340816508590

- BakrisGLTotoRDMcCulloughPARochaRPurkayasthaDDavisPEffects of different ACE inhibitor combinations on albuminuria: results of the GUARD studyKidney Int200873111303130918354383

- ChaturvediNPortaMKleinREffect of candesartan on prevention (DIRECT-Prevent 1) and progression (DIRECT-Protect 1) of retinopathy in type 1 diabetes: randomised, placebo-controlled trialsLancet200837296471394140218823656

- HubnerRHogemannAMSunzelMRiddellJGPharmacokinetics of candesartan after single and repeated doses of candesartan cilexetil in young and elderly healthy volunteersJ Hum Hypertens199711Suppl 2S19S259331000

- HanssonLLithellHSkoogIStudy on COgnition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE): baseline characteristicsBlood Press200092314615110854001

- ZanchettiAElmfeldtDFindings and implications of the Study on COgnition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE) – a reviewBlood Press2006152717916754269

- Cohen-SolalAMcMurrayJJSwedbergKBenefits and safety of candesartan treatment in heart failure are independent of age: insights from the Candesartan in Heart failure – Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity programmeEur Heart J200829243022302818987098

- PloskerGLKeamSJCandesartan cilexetil: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in chronic heart failure and hypertensionPharmacoeconomics200624121249127217129078