Abstract

Stewart–Treves syndrome is a rare invasive lymphangiosarcoma linked with chronic lymphedema after mastectomy for breast cancer. Given the aggressive nature of the tumor, preventative measures and early diagnosis are important. This case is the first dermoscopic description of the lymphangiosarcoma of Stewart–Treves syndrome; it shares similar dermoscopic findings with angiosarcoma of the scalp after irradiation, with findings of a pink-white background, white lines and a combination of red, blue and black structureless areas containing red dots and globules. The lack of conspicuous lacunae make dermoscopy useful for ruling out other differentials such as benign vascular proliferations. Color heterogeneity and vascularization in dermoscopy might inform the clinician of a high percentage of tumor cells on histology.

The lymphangiosarcoma of Stewart–Treves (LST) syndrome is a rare tumor, yet it is a very aggressive malignancy. This is why early diagnosis is mandatory.

Dermoscopy may be a great tool in the early diagnosis and monitoring of LST.

This first dermoscopic description of the LST syndrome shows a lack of conspicuous lacunae with findings of a pink-white background, white lines and a combination of red, blue and black structureless areas containing red dots and globules.

Dermoscopy is also useful for ruling out other differentials, such as benign vascular proliferations.

Color heterogeneity and vascularization in dermoscopy might have a prognostic implication, because it may inform the clinician of a high percentage of tumor cells on histology.

First described in 1948, cutaneous lymphangiosarcoma of Stewart–Treves syndrome (LST) is a rare, aggressive malignancy that originates from the endothelial cells lining lymphatic vessels, seen most often 10 years after a successful radical mastectomy for breast carcinoma with chronic residual lymphedema of the upper limb [Citation1–3]. Its clinical and histologic features are often indistinguishable from angiosarcoma [Citation4]. LST usually arises in elderly individuals, and the prognosis is generally poor with only 15% of patients being alive 5 years after diagnosis and treatment [Citation5].

The diagnosis can be delayed because early lesions may be misdiagnosed easily as traumatic ecchymosis, pyogenic granuloma or other benign vascular proliferations by patients and physicians [Citation6].

To date, dermoscopy of lymphangiosarcoma has not been described, we report the first dermoscopic description of the LST.

Observation

A 76-year-old patient, with a history of 12 years residual lymphoedema after radical mastectomy followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy for invasive ductal carcinoma of the left breast, presented with 3-month history of confluent angiomatous purple and black nodules on the mastectomy scar on the left chest wall and the left upper limb, with bleeding and hemorrhagic crusts ().

Clinical presentation of confluent angiomatous purple and black nodules on the mastectomy scar on the left chest wall and the left upper limb, with bleeding and hemorrhagic crusts.

Cutaneous metastasis of breast cancer, angiosarcoma, lymphangiosarcoma in a Stewart–Treves syndrome or Kaposi’s sarcoma were the main suspected diagnoses.

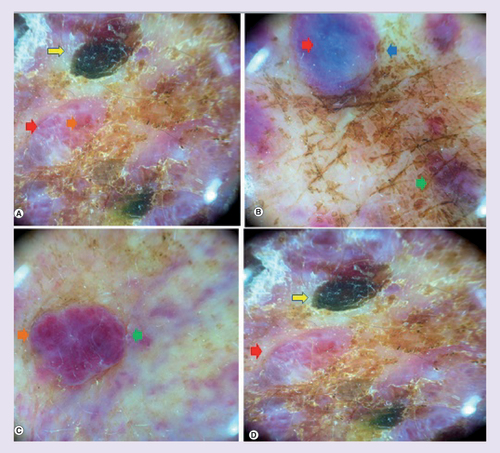

Dermoscopy revealed findings of a pink-white background, white lines and a combination of red, blue and black structureless areas containing red dots and globules, without any conspicuous lacunae ().

White lines and white structureless areas (red arrows) on a pink-white background, the nodular component show a color heterogeneity as purple and milky red globules (green arrow) with vascularization as red dots and globules inside them (orange arrow), blue (blue arrow) and black structureless areas (yellow arrow).

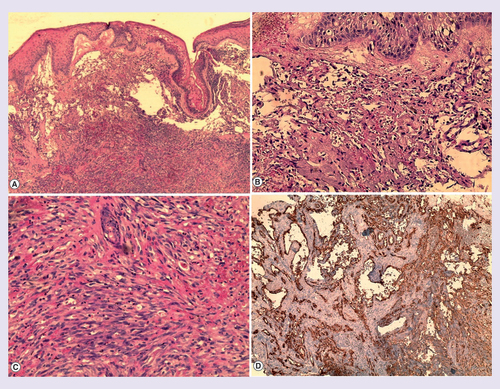

A cutaneous biopsy was performed, with findings of a proliferation occupying the entire dermis, anastomizing and dilated vascular slits with irregular lumina lined by atypical endothelial cells and mitotic figures, in the deep dermis; we observed a massive proliferation of atypical fusiform cells, extensive extravasation of red blood cells without necrosis, Pearls stain was positive. Immunochemistry showed positivity for CD31 and CD34 and negativity for HHV-8, the proliferation rate (Ki-67) was about 50% ().

(Hematoxylin–eosin stain) (A) 20× magnification (B) 40× magnification (C) 100× magnification. (A,B,C) Tumor proliferation occupying the entire dermis, anastomozing, irregular and dilated vascular slits with irregular lumina lined by atypical endothelial cells, which showed nuclear atypia with mitotic figures. In the deep dermis; massive proliferation of atypical fusiform cells with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and cytoplasmatic vacuoles, extensive extravasation of red blood cells without necrosis. (D) Immunochemistry for CD31 and CD34.

The lack of HHV-8 ruled out a Kaposi’s sarcoma, and the positivity of CD31 and CD34 in the context of residual lymphedema after mastectomy confirmed the diagnosis of LST.

Wide local excision was not possible in this case; palliative hemostatic radiotherapy and chemotherapy (five courses of Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2) were prescribed to the patient, but unfortunately she developed regional and distant metastases and died within a few months.

Discussion

Given the increased incidence of breast neoplasia treated by surgery with residual lymphedema, the incidence of LST may also increase. Curative treatment of lymphangiosarcoma is surgical. However, resection and/or amputation are not always realistic options when considering anatomic location or disease progression. Radiotherapy as primary or adjuvant treatment has improved survival in many patients, systemic chemotherapy is reserved for locally advanced nonoperable or metastatic forms [Citation4]. This imposes measures to prevent lymphedema, in addition to long-term follow-up of these patients in order to avoid delayed diagnosis, which was the case of our patient who had an advanced local condition.

McConnell and Haslam proposed in 1959 three evolutionary stages of postmastectomy lymphangiosarcoma; the first stage is a prolonged lymphedema causing fat and collagen degeneration, the second stage is a premalignant lymphangiomatosis with multiple foci of small, proliferating channels and hyperplastic endothelial cells, induration or hemorrhage in in the dermis and subcutis and the third stage is the malignant infiltrating lymphangiosarcoma [Citation7].

Clinical examination and dermoscopy may be based on this staging to detect premalignant transformation and to prevent the onset of the malignant aggressive tumor. White lines and color in dermoscopy represent collagen modifications; the color heterogeneity that we observed in dermoscopy is the reflection of anarchic proliferation of endothelial cells and hemorrhage.

Dermoscopy would also help in ruling out other differential diagnoses including benign vascular diseases like angioma, and lymphangioma [Citation8], where the color is homogeneously pink or red without any vascularization inside lacunae. Dermoscopy can also rule out Kaposi sarcoma based on the rainbow pattern and violaceous structureless areas [Citation9]. However, we cannot pretend that dermoscopy could make the difference between a diagnosis of this tumor and other malignancies like melanoma and metastatic carcinoma to the skin [Citation10], at this moment, a better dermoscopic characterization of the disease may allow this in the future.

There is a little confusion between LST and angiosarcoma. Some authors divided angiosarcoma into three clinical subtypes: classical angisarcoma (head and neck type), angiosarcoma arising in the context of residual lymphedema after mastectomy (LST syndrome for other authors), and angiosarcoma arising in irradiated skin [Citation11].

Histologically, lymphangiosarcoma and angiosarcoma may have similar findings, even in tumors of confirmed lymphatic origin, some structures will show differentiation toward blood vessels [Citation4].

As a result of these histological similarities, dermoscopy of angiosarcoma and LST may show also similar findings. In the work of Lallas et al. of uncommon skin tumors [Citation12], and in other case reports of angiosarcomas of the scalp [Citation13–15], dermoscopic findings of white lines and combinations of red, purple and blue color were described in angiosarcoma, this is almost the same dermoscopic findings in LST syndrome that we report in this paper. Pink-white color was also described in four cases of radiation-induced angiosarcoma – three of them had a history of breast carcinoma without lymphedema – with red to purple structureless areas, central crusts, and polymorphic vessels in the nodular component of lesions [Citation11,Citation16].

The color heterogeneity and vascularization on dermatoscopy are indicators of a high percentage of tumor cells on histology and a poor prognosis [Citation15]; this was also noticed in our case where we observed these findings in nodular lesions with massive proliferation of atypical cells.

The key to improve survival of patients with LST is the early diagnosis. Primary care physicians may perform dermoscopy regularly in patients with pertinent history and suspicious clinical presentations [Citation6], in order to increase the accuracy of the physical examination, and to detect this aggressive tumor at an early stage based on the white lines, color heterogeneity and vascularization in dermoscopy without conspicuous lacunae.

Conclusion

In this first dermoscopic description of LST, we point out the role of dermoscopy in the early diagnosis of this aggressive tumor and the monitoring of the mastectomy scar with residual lymphedema.

Future perspective

Dermoscopy can be a great tool in the diagnosis and monitoring of LST, with well-described dermoscopic features, that may help the clinicians in order to differentiate it from other malignancies like melanoma and metastatic carcinoma to the skin, which is not possible at this moment.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Informed consent disclosure

The authors state that they have obtained verbal and written informed consent from the patient/patients for the inclusion of their medical and treatment history within this case report.

References

- Pantoja E , Beecher TS , Cross VF . Cutaneous lymphangiosarcoma of Stewart–Treves. Cutis 17(5), 883–886 (1976).

- Miglino B , Maldi E , Tiberio R et al. Stewart–Treves syndrome of the breast after quadrantectomy for breast carcinoma. Breast J. 21(5), 552–554 (2015).

- McKeown D , Boland P . Stewart–Treves syndrome: a case report. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 95(5), e6–e8 (2013).

- Mamelak AJ , Collie MRV , Kroll R , Hanson ML , Harris HM . Lymphangiosarcoma of the scalp. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 18(2), 132–136 (2014).

- Marando A , Bernasconi B , Sabatino D , Militti L , Capella C . Complex karyotype in a case of cutaneous lymphangiosarcoma associated with chronic lymphedema of the lower limb. Pathol. Res. Pract. 210(12), 1138–1141 (2014).

- Cui L , Zhang J , Zhang X et al. Angiosarcoma (Stewart–Treves syndrome) in postmastectomy patients: report of 10 cases and review of literature. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8(9), 11108–11115 (2015).

- McConnell AH , Haslam P . Angiosarcoma in post-mastectomy lymphedema:report of five cases and review of the literature. Br. J. Surg. 46, 322–332 (1959).

- Sanada T , Hata H , Sato K et al. Usefulness of dermoscopy in distinguishing benign lesions from angiosarcoma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 42(6), 676–678 (2017).

- Satta R , Fresi L , Cottoni F . Dermoscopic rainbow pattern in Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions: our experience. Arch. Dermatol. 148(10), 1207 (2012).

- Sharma A , Schwartz RA . Stewart-Treves syndrome: pathogenesis and management. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 67(6), 1342–1348 (2012).

- De Giorgi V , Grazzini M , Rossari S et al. Dermoscopy pattern of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Eur. J. Dermatol. 21(1), 113–114 (2011).

- Lallas A , Moscarella E , Argenziano G et al. Dermoscopy of uncommon skin tumors: dermoscopy of uncommon skin tumors. Australas. J. Dermatol. 55(1), 53–62 (2014).

- Minagawa A , Koga H , Okuyama R . Vascular structure absence under dermoscopy in two cases of angiosarcoma on the scalp. Int. J. Dermatol. 53(7), e350–e352 (2014).

- Zalaudek I , Gomez-Moyano E , Landi C et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathological features of spontaneous scalp or face and radiotherapy-induced angiosarcoma: dermoscopic patterns of angiosarcoma. Australas. J. Dermatol. 54(3), 201–207 (2013).

- Oiso N , Matsuda H , Kawada A . Various color gradations as a dermatoscopic feature of cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: dermoscopy of cutaneous angiosarcoma. Australas. J. Dermatol. 54(1), 36–38 (2013).

- Figueroa-Silva O , Argenziano G , Lallas A , Longo C , Piana S , Moscarella E . Dermoscopic pattern of radiation-induced angiosarcoma (RIA). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 73(2), e51–e55 (2015).