SUMMARY

Recent advances in breast cancer (BC) treatment and improved screening have resulted in an increasing number of BC survivors. However, since recurrences are still a relatively common event there is a critical need to investigate modifiable factors that could impact disease recurrence and long-term prognosis. There is substantial evidence from observational studies and increasingly from randomized controlled trials, showing that weight management, increased physical activity and dietary modification may be effective methods to improve BC survival and reduce recurrences, due to their interrelated beneficial effects on systemic inflammation, circulating reproductive hormones and metabolic imbalances. Although ongoing randomized controlled trials should be able to confirm the role of these lifestyle factors on BC prognosis, further research is needed to establish specific lifestyle recommendations.

• Improvements in breast cancer screening and major advances in treatment have significantly increased breast cancer prognosis.

• Breast cancer recurrences are still a relatively common event.

• There is a critical need to investigate modifiable factors that could impact breast cancer recurrence and survival.

• Epidemiological and clinical findings suggest that weight management, physical activity and dietary factors could influence breast cancer prognosis, however there is still no conclusive evidence from clinical trials.

• There are several large ongoing combined lifestyle randomized controlled trials that should be able to clarify if these behavioral modifications are effective at improving breast cancer prognosis.

• Several interrelated biological mechanisms could explain the role of diet, physical activity and weight management in breast cancer prognosis, including their effects on systemic inflammation, circulating reproductive hormones and metabolic imbalances.

• It is a public health priority to move from current evidence to practical changes in clinical practice.

• Specific and evidence-based lifestyle recommendations need to be given to women diagnosed with breast cancer, along with practical tools and strategies to help implement them.

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common tumor in women, with approximately 1.7 million new cases diagnosed in 2012 worldwide and it is also the first cause of cancer death among women [Citation1]. Over the last decades, improved screening and major advances in treatment have significantly increased BC prognosis. In all European regions, except eastern Europe, the mean age-standardized 5-year survival ranged from 76 to 86% for women diagnosed between 2000 and 2007 [Citation2]. In the USA, relative survival rates for women diagnosed with BC between 2001 and 2007 are 89% at 5 years after diagnosis [Citation3]. Despite the relatively high 5-year survival rates, large differences are still observed across age and stage at diagnosis or tumor characteristics, with the most favorable prognosis observed in women diagnosed after 40 years old, in tumors ≤2.0 cm and those expressing estrogen and/or progesterone receptors [Citation3,Citation4]. In addition, 5-year BC recurrence has been reported to range from 7 to 22% according to cancer subtype [Citation5]. Therefore, for the effective management of BC, there is a critical need to investigate modifiable factors that could impact disease recurrence and long-term prognosis.

Current evidence not only indicates that adiposity and physical inactivity are associated with risk of developing BC [Citation6,Citation7] but also suggests they could be important determinants of BC prognosis, independently or through their influence on weight control [Citation8]. Therefore, the aim of the present paper is: to review the current epidemiological evidence on the association between diet, weight control and physical activity (PA) and BC prognosis; to briefly mention the ongoing studies designed to assess the role of lifestyle interventions on BC prognosis; to identify the biological mechanisms likely to underlie these associations; and to discuss actual results and future research perspectives.

Epidemiological evidence

• Effects of diet & weight control on BC outcomes

Although several dietary factors or dietary patterns have been implicated in the risk of developing BC [Citation7,Citation9,Citation10], the evidence is still largely inconclusive, and according to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research 2007 report alcoholic drinks are the only convincing risk factor [Citation7]. Observational studies in BC survivors have also linked certain dietary factors to several measures of prognosis, although for total fat the evidence is still inconsistent, and for fruit, vegetables, whole grains and fiber the evidence is fairly weak [Citation8,Citation11]. Moreover, the only two large randomized dietary intervention trials conducted in BC patients, the WIN [Citation12] and WHEL studies [Citation13] have not provided clear support for the role of diet in BC recurrence. The WINS study dietary intervention assigned 2437 postmenopausal women with early-stage BC to either a low-fat (less than 15% energy from lipids) or standard diet. After approximately 5 years of follow-up, the intervention group had a 24% (p = 0.034) lower risk of BC recurrence compared with the control group with an effect of the intervention mostly observed in women with estrogen receptor-negative tumors [Citation12]. By contrast, the WHEL study [Citation13] found that an intervention diet rich in vegetables, fruit and fiber and low in fat (15–20%) compared with a government recommended ‘5-a-day’ control diet did not reduce risk of BC recurrence or mortality; after a 7.3-year follow-up the risk of recurrences among the 3088 pre- and post-menopausal BC patients was 16.7% in the intervention group and 16.9% among controls. Several reasons have been put forward to explain these discrepancies, including the fact that WHEL trial volunteers had eating habits that were much healthier than the average BC survivor population [Citation13], and therefore dietary changes may have had a greater benefit in women already eating below current recommendations [Citation14]. However, the most remarkable difference is that in WHEL there was no significant weight modification either in the control or intervention group (<1 kg difference in average weight between study arms at any time point), while in WINS there was a significant, though unplanned, weight reduction (2.4 kg on average at 5 years; p = 0.005) in the intervention arm [Citation13,Citation14]. These results suggest that energy balance could play a significant role in BC cancer prognosis, and might be more important than the modest effects of total fat intake reduction or other dietary factors. This is particularly relevant considering the high prevalence of overweight and obesity and sedentary lifestyles among women diagnosed with BC [Citation15,Citation16]. In addition, weight gain is commonly observed in BC survivors; as many as 50% of women experience significant weight gain during their cancer treatment [Citation10]. Among those who gain weight, average increases typically range from 2.5 to 6.2 kg [Citation17]. Weight gain is more common in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy, appears to be especially pronounced in premenopausal women, and often involves unfavorable changes in body composition, characterized by high body fat and low lean body mass [Citation10].

Observational data from research on BC survivors consistently indicate that women with BC who are overweight or obese or gain weight after diagnosis have a poorer prognosis, with a greater risk of BC recurrence or death compared with lighter women or those who maintain their weight [Citation18–20]. A recent meta-analysis of 82 follow-up studies, including 213,075 BC survivors, found that compared with a normal weight, prediagnosis obesity was associated with a 41% increased risk of overall mortality, and overweight was associated with a 7% significant increased risk [Citation21]. Postdiagnosis BMI was also significantly associated with BC specific mortality, with a 35 and 11% increased risk for obese and overweight women respectively. A review published in 2010 [Citation8] on adiposity and additional BC events found that out of the six observational studies identified (including several large cohorts) four reported significant associations, with an approximately 10% increased risk of a BC recurrence related to postdiagnosis obesity. In addition, there is a greater risk of cancer treatment complications and numerous comorbidities that are related to being overweight or obese. Weight gain after diagnosis is also associated with worse prognosis [Citation22] with several cohort studies have shown that weight gain during chemotherapy decreased disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival [Citation23–25]. This suggests that intentional weight loss or weight maintenance after diagnosis might improve BC prognosis; however, this area has not been widely studied. The WINS study [Citation12], which reported reduced BC recurrence after a dietary intervention also found a 6-pound difference in weight between the intervention and control group after the 5-year follow-up, suggesting weight loss may influence DFS. However, there is currently no conclusive evidence from clinical trials indicating that weight loss or maintenance after diagnosis increases survival or reduces recurrences.

• Effects of PA on BC outcomes

There is accumulating evidence that PA protects against postmenopausal BC whereas the evidence suggesting that it protects against premenopausal BC is limited [Citation7]. These results have led investigators to assess the effects of postdiagnosis PA in BC survivors and the resulting studies can be divided into two main categories, those focused on short-term effects such as fatigue, quality of life (QoL), anthropometry and cardiorespiratory fitness and those focused on BC recurrence and survival.

To date, numerous randomized controlled trials have studied the short-term effects of postdiagnosis exercise in BC survivors. The meta-analyses published by McNeely and Bicego that exclusively focused on randomized controlled trials in BC survivors concluded that exercise was an effective intervention to improve QoL [Citation26,Citation27]. Positive effects of exercise were also reported for cardiorespiratory fitness, physical functioning and fatigue [Citation26]. An important limitation of these reviews was the nonspecificity with respect to the timing of the exercise intervention, therefore more recent meta-analyses have differentiated the interventions offered during and after adjuvant therapy. Two meta-analyses published in 2012 assessed the effect of PA in adults who had completed their main cancer treatment [Citation28,Citation29]. Although one review concluded that PA was associated with improvements in IGF-I, muscle strengths, fatigue, depression and QoL [Citation28], the other review only showed an increase in health-related QoL in the exercise group, and no improvement was observed for anxiety, depression, well-being and fatigue [Citation29]. Two recent meta-analyses also evaluated the effects of exercise on cancer-related fatigue and psychological outcomes in BC patients receiving adjuvant therapy [Citation30,Citation31]. The meta-analysis focused on cancer-related fatigue revealed significant differences in fatigue between the intervention group and the control group [Citation30]; however, the results were not consistent for all fatigue measures and only observed among Asian populations. The meta-analysis assessing the psychological effects of exercise showed significant improvement for fatigue, QoL and depression as well as a significant inverse dose-response between the volume of prescribed exercise and fatigue and QoL [Citation31].

The results presented above show evidence for some short-term effects of PA in BC survivors; however, the role of exercise on long-term outcomes such as recurrence and survival have not yet been widely studied and evidence is so far limited to observational studies. In a recent meta-analysis postdiagnosis PA was associated with a reduction in BC death of 34% (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.57–0.77), all causes mortality of 41% (HR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.53–0.65) and disease recurrence of 24% (HR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.66–0.87) [Citation32]. These results were confirmed by a subsequent meta-analysis, which found that PA postdiagnosis reduced total mortality by 48% (HR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.42–0.64) and BC mortality by 28% (HR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.60–0.95) [Citation33]. Both meta-analyses also indicated that the effect of postdiagnosis PA on total mortality was more pronounced among patients with estrogen receptor-positive tumors. To our knowledge, to date, there is only one paper based on randomized data that has assessed the role of postdiagnosis exercise on BC survival. This paper reports the exploratory follow-up of an RCT originally designed to assess the role of aerobic and resistance training during adjuvant therapy on QoL in 242 BC patients. The results suggest that adding exercise to standard chemotherapy may improve BC outcomes [Citation34]; 8-year DFS was 82.7% for the exercise group compared with 75.6% for the control group (HR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.37–1.24) and slightly stronger effects were observed for overall survival (HR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.27–1.33) and recurrence-free survival (HR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.30–1.11). This result is in agreement with those of the meta-analyses of observational studies described previously [Citation32,Citation33]. However, the exploratory nature of the analysis and its underpowered sample size to provide definitive conclusions, points to the need to define Phase III trials assessing the role of postdiagnosis exercise on BC survival.

Ongoing trials based on lifestyle interventions

Growing evidence strongly suggests that weight control may reduce BC recurrence. In addition, diet and PA have been found to be associated with improved BC prognosis. Since weight control can be achieved through calorie restriction or increase in calorie expenditure, these findings suggest that lifestyle interventions combining dietary and PA components may represent the best strategy to improve BC prognosis and also increase the QoL of BC survivors. To our knowledge four trials designed with this objective are currently ongoing with no primary end point results published to date.

The DIANA-5 study [Citation35] is a multi-institutional RCT set in Italy designed to assess the effectiveness of an intensive Mediterranean and macrobiotic style diet combined with moderate PA in reducing BC recurrences. Between 2008 and 2010, the study recruited 1208 women with early-stage invasive BC and at high risk of recurrence because of metabolic or endocrine milieu. Another European trial, set up in Germany, the SUCCESS C study, aims to include 3547 women with early-stage, HER2/neu-negative BC and will involve two successive randomization processes [Citation36]. The first one will compare two chemotherapy protocols in order to evaluate the role of anthracycline-free chemotherapy. The second one will compare DFS in overweight and obese patients receiving either a telephone-based individualized lifestyle intervention program aiming at moderate weight loss or general recommendations for a healthy lifestyle alone. The ENERGY trial [Citation37] is a feasibility trial set in the USA designed to demonstrate the effect of a lifestyle intervention in achieving a sustained weight loss in overweight and obese women diagnosed with early-stage BC. This trial, involving currently 693 women, is a vanguard component of a fully-powered trial that will include approximately 2500 women and will examine the effect on cancer-specific outcomes. The PREDICOP study is a multicentric RCT designed to assess the effects of a lifestyle intervention involving diet, weight control and PA on BC prognosis. A one-arm prepost feasibility study, involving the same intervention, showed a significant weight loss and significant increases in QoL and cardiorespiratory fitness in overweight and obese BC survivors [Citation38]. The recruitment of the PREDICOP study is currently ongoing in eight hospitals in and around Barcelona (Spain) and the aim is to include 2000 nonmetastatic BC patients, without restriction of menopausal status or risk of recurrence and including normal as well as overweight and obese women.

Mechanistic considerations

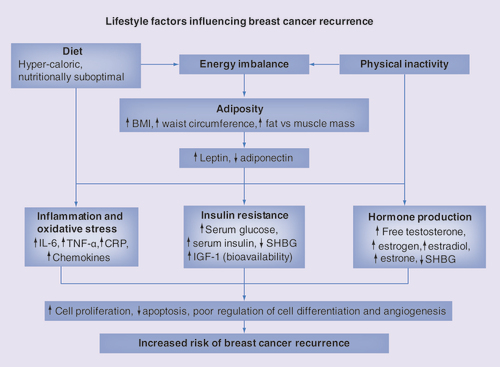

Several biological mechanisms could explain the interrelated effects of diet, adiposity and PA on risk of BC recurrences and overall prognosis (), including endogenous reproductive hormones; chronic inflammation and; metabolic changes such as insulin resistance [Citation39–42]. Adiposity has a key role in the production of reproductive hormones, due to adipose tissue’s endocrine function, expressing and secreting various hormones including estrogen and adipose tissue’s ability to convert androgens to estrogen. In support of this, obese women, in particular postmenopausal, have higher concentrations of circulating estrogen, estrone, estradiol and testosterone and lower levels of SHBG [Citation42]. The active hormones estradiol and testosterone have been implicated in tumor growth due to their ability to directly promote cellular division and proliferation in the breast epithelium and inhibit apoptosis [Citation43] and through indirect effects on hormone production and growth factors. Therefore, increased risk of BC recurrences in patients who are overweight/obese or gain weight after diagnosis may be explained by their raised levels of estrogens and androgens [Citation44,Citation45]. Dietary factors may also alter sex hormone levels and consequently influence BC prognosis. For instance, the WHEL study’s intervention diet lowered serum bioavailable estradiol in BC survivors [Citation46]. Sedentary lifestyles have also been linked to higher levels of estrogens and androgens [Citation47].

Adiposity, in particular centrally located adipose tissue, is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation () that is implicated in cancer pathology including risk of BC and BC survival and recurrence [Citation42,Citation48]. Adipose tissue’s adipocytes produce various inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, TNF-α and adiponectin, which along with CRP (produced in the liver) [Citation49] are higher in obese subjects [Citation40]. Inflammation can lead to tumor growth and progression through its influence on cellular proliferation, tumor survival and metastasis. There is accumulating evidence linking inflammation to BC prognosis [Citation42], since higher levels of many of these inflammatory markers predict worse BC survival (CRP, IL-6) and increased risk of recurrence (CRP) [Citation48,Citation50–52]. In turn, moderate calorie restriction has been related to decreased chronic inflammatory markers [Citation53], and may therefore reduce BC recurrences. Certain dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, have been shown to have anti-inflammatory effects, reducing CRP, IL-6 and chemokines [Citation54]. The beneficial effects of postdiagnosis PA on BC prognosis and survival could be explained by ability of exercise to reduce, directly or indirectly (via reduction in visceral fat mass), chronic low-grade inflammation [Citation55,Citation56]. Indeed, according to Beavers and Gleeson, skeletal muscles may act as an endocrine organ and by contraction induce myokine production associated with a reduced production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. A meta-analysis focusing exclusively on summarizing the randomized controlled trials evaluating the effects of postdiagnosis PA on biomarkers in BC survivors indicated that PA may result in beneficial changes in certain inflammatory biomarkers, although no evidence for a role of interleukins was found [Citation57]. Adipose tissue is correlated with higher concentrations of leptin and lower levels of adiponectin which are related to increased risk of BC and tumor growth and progression [Citation58].

Obesity, above all abdominal obesity is linked to metabolic disturbances, including elevated serum glucose and insulin levels, increased insulin resistance and compensatory chronic hyperinsulinemia () [Citation42,Citation59]. Increased insulin levels in turn lead to reduced liver synthesis of IGF binding proteins, resulting in increased levels of bioavailable insulin and IGF-1, which have been shown to stimulate cellular proliferation and differentiation of mammary cells and inhibit apoptosis in many tissues. Elevated serum levels of insulin, IGF-1 and glucose are associated with poorer BC prognosis and greater risk of recurrence [Citation60–63]. In addition, obesity induced hyperinsulinemia causes a reduction in the synthesis of SHBG leading to increased levels of circulating steroids, which as mentioned above has been linked to poorer BC prognosis and recurrences. The beneficial effects of postdiagnosis PA in BC survivors on fatigue and BC prognosis effects might also be due to reductions in circulating serum levels of IGFs and IGF binding proteins [Citation64].

Certain diets may also be better at promoting sustained weight loss and/or may improve BC relevant biomarkers independent of their effect on weight. Many small clinical trials have been developed to address the overweight/obesity and weight gain often observed in women diagnosed with BC [Citation37]. The majority have found that interventions including dietary counseling (with or without PA components) have achieved significant weight losses in this target population. However, these trials have had more success when targeted at women who have finished adjuvant treatment [Citation38,Citation65–68], compared with weight loss interventions carried out during treatment [Citation37].

However, the optimal macronutrient distribution of weight-loss diets for BC patients is still not established [Citation40,Citation42], although low-carbohydrate diets [Citation69] may be favorable over the traditionally recommended low-fat diets [Citation11,Citation42,Citation70], as they have been found to reduce serum glucose and insulin levels and increase insulin sensitivity [Citation71–73]. While diets abundant in fruit and vegetables may also potentially contribute to improving BC prognosis, possibly due to their phytochemicals which have the ability to regulate cell growth, differentiation and inhibition of angiogenesis and have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant role [Citation74], the epidemiological evidence is still weak [Citation7,Citation75].

Conclusion & future perspective

There is increasing insight into how women who have been diagnosed with BC can modify certain behaviors in order to reduce their risk of BC recurring and increase overall survival. Weight management, in particular reducing excess abdominal adiposity, increased PA and dietary modification may be the promising tools, due to their consequential interrelated beneficial effects on systemic inflammation, circulating reproductive hormones and metabolic imbalances.

Current international nutritional and PA guidelines for cancer survivors [Citation6,Citation75] recommend that after cancer treatment weight gain or loss should be managed (to reach an ideal weight) through a combination of PA and diet (low-energy dense foods, limiting portion sizes, limiting foods high in fat and sugar etc.). PA is also recommended, independent from weight loss goals, with the aim to maintain activity as much as feasible during treatment and increase levels to moderate/vigorous intensity once treatment is complete [Citation75,Citation76]. Although the evidence is still not conclusive on whether these behavioral strategies can help prevent BC reoccur, BC survivors will at least gain other health benefits from increasing PA and following a healthy diet, and even weight losses of 5–10% can have a significant impact on health [Citation75].

The ongoing combined lifestyle randomized controlled trials should therefore be able to give greater insight into whether these lifestyle changes are effective at improving BC prognosis, further elucidate the mechanisms behind the interconnected relationship between diet, PA and adiposity, and help identify early predictive markers of women at high risk. However, a common limitation of these studies is that even if they do confirm that lifestyle factors can reduce BC recurrence and improve other BC related outcomes, it will be difficult to disentangle if the effect is due to PA, dietary modification or their influence on weight maintenance. In addition, further studies are needed to clarify the optimal timing, frequency and intensity of PA and the most effective and appropriate dietary recommendations that can benefit weight maintenance and other BC risk factors. Future intervention studies also need to address the challenges of measuring PA and diet, which is a limitation in some previous studies. PA is a complex construct and the choice of assessment instrument is a difficult decision as questionnaires and accelerometry-based objective measures have strengths and limitations that need to be acknowledged and taken into account [Citation77]. Measuring diet in overweight and obese participants is also particularly challenging, as they are more prone to under-report dietary intake than lean participants, therefore implausible dietary reporting should be accounted for in data analyses [Citation78].

If the ongoing randomized controlled trials prove to be effective in improving BC prognosis, then a new generation of studies involving more affordable intervention programs are needed because most of the interventions currently offered in these trials have costs that can only be handled in small, highly controlled environments, and which are impossible to implement at a larger scale, especially considering the current world economy in which healthcare budgets are increasingly cut. On the other hand, new strategies are needed to reach a wider part of the target population, as so far most experimental studies in BC survivors have been set-up in very specific settings. For instance, numerous studies have focused on specific subgroups of BC survivors (white, middle-aged, postmenopausal, overweight or obese or high risk of recurrence), which limits the generalizability of their findings to all BC survivors. In addition, lifestyle interventions often include long intense programmes in supervised hospital-based settings, which are not necessarily tailored to the patient’s interests or often busy lifestyles. Providing support to BC patients in their lifestyle changes through new technologies available on the internet or smartphone applications may help reach a wider BC survivor population and be more cost effective and feasible on a larger scale.

Finally, because a cancer diagnosis as often been described as ‘a teachable moment’, with BC patients being very motivated to make lifestyle changes [Citation79], it is important to find ways to try to convert this one-time event into an opportunity to set up effective long-term behavioral changes that can maximise their health and wellbeing. The ongoing research should help confirm and consolidate the existing nutrition and PA guidelines, and provide practical tools and strategies to help implement them [Citation75]. While it is a public health priority to move from current evidence to applied changes in clinical practice, this process is not complete as yet. Although some guidelines are now available, clinicians do not systematically provide BC patients with this information. As a consequence numerous BC survivors are still overweight/obese or gain weight after treatment and continue to lead inactive lifestyles, which is likely to increase their risk of BC recurring and decrease their overall survival and QoL.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Ferlay J , ShinHR, BrayFet al.; GLOBOCAN. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. International Agency for Research on Cancer v1.0.International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France (2012). http://globocan.iarc.fr.

- De Angelis R , SantM, ColemanMPet al. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5 – a population-based study. Lancet Oncol.15(1), 23–34 (2014).

- American Cancer Society . Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2011–2012.American Cancer Society Inc., Atlanta, GA, USA (2014).

- Allemani C , MinicozziP, BerrinoFet al. Predictions of survival up to 10 years after diagnosis for European women with breast cancer in 2000–2002. Int. J. Cancer132(10), 2404–2412 (2013).

- Minicozzi P , BellaF, TossAet al. Relative and disease-free survival for breast cancer in relation to subtype: a population-based study. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol.139(9), 1569–1577 (2013).

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research . Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective.AICR, Washington, DC, USA (2007).

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research . Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Breast Cancer.AICR, Washington, DC, USA (2010).

- Patterson RE , CadmusLA, EmondJA, PierceJP. Physical activity, diet, adiposity and female breast cancer prognosis: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Maturitas66(1), 5–15 (2010).

- Brennan SF , CantwellMM, CardwellCR, VelentzisLS, WoodsideJV. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.91(5), 1294–1302 (2010).

- Vance V , MourtzakisM, McCargarL, HanningR. Weight gain in breast cancer survivors: prevalence, pattern and health consequences. Obes. Rev.12(4), 282–294 (2011).

- Rock CL , Demark-WahnefriedW. Can lifestyle modification increase survival in women diagnosed with breast cancer?J. Nutr.132(11 Suppl.), 3504S–3507S (2002).

- Chlebowski RT , BlackburnGL, ThomsonCAet al. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. J. Natl Cancer Inst.98(24), 1767–1776 (2006).

- Pierce JP , NatarajanL, CaanBJet al. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: the women’s healthy eating and living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA298(3), 289–298 (2007).

- Nelson N . Dietary intervention trial reports no effect on survival after breast cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst.100(6), 386–387 (2008).

- Bourke L , HomerKE, ThahaMAet al. Interventions to improve exercise behaviour in sedentary people living with and beyond cancer: a systematic review. Br. J. Cancer110(4), 831–841 (2014).

- Courneya KS , KatzmarzykPT, BaconE. Physical activity and obesity in Canadian cancer survivors: population-based estimates from the 2005 Canadian community health survey. Cancer112(11), 2475–2482 (2008).

- Irwin ML , McTiernanA, BaumgartnerRNet al. Changes in body fat and weight after a breast cancer diagnosis: influence of demographic, prognostic, and lifestyle factors. J. Clin. Oncol.23(4), 774–782 (2005).

- Chlebowski RT , AielloE, McTiernanA. Weight loss in breast cancer patient management. J. Clin. Oncol.20(4), 1128–1143 (2002).

- McTiernan A , IrwinM, VongruenigenV. Weight, physical activity, diet, and prognosis in breast and gynecologic cancers. J. Clin. Oncol.28(26), 4074–4080 (2010).

- Bradshaw PT , IbrahimJG, StevensJet al. Postdiagnosis change in bodyweight and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. Epidemiology23(2), 320–327 (2012).

- Chan DS , VieiraAR, AuneDet al. Body mass index and survival in women with breast cancer-systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 82 follow-up studies. Ann. Oncol.25(10), 1901–1914 (2014).

- Ligibel J . Obesity and breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park)25(11), 994–1000 (2011).

- Kroenke CH , ChenWY, RosnerB, HolmesMD. Weight, weight gain, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J. Clin. Oncol.23(7), 1370–1378 (2005).

- Nichols HB , Trentham-DietzA, EganKMet al. Body mass index before and after breast cancer diagnosis: associations with all-cause, breast cancer, and cardiovascular disease mortality. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.18(5), 1403–1409 (2009).

- Thivat E , TherondelS, LapirotOet al. Weight change during chemotherapy changes the prognosis in non-metastatic breast cancer for the worse. BMC Cancer10, 648 (2010).

- McNeely ML , CampbellKL, RoweBHet al. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ175(1), 34–41 (2006).

- Bicego D , BrownK, RuddickMet al. Effects of exercise on quality of life in women living with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast J.15(1), 45–51 (2009).

- Fong DY , HoJW, HuiBPet al. Physical activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ344, e70 (2012).

- Mishra SI , SchererRW, GeiglePMet al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane. Database. Syst. Rev.8, CD007566 (2012).

- Zou LY , YangL, HeXL, SunM, XuJJ. Effects of aerobic exercise on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol.35(6), 5659–5667 (2014).

- Carayol M , BernardP, BoicheJet al. Psychological effect of exercise in women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant therapy: what is the optimal dose needed? Ann. Oncol. 24(2), 291–300 (2013).

- Ibrahim EM , Al HomaidhA. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: meta-analysis of published studies. Med. Oncol.28(3), 753–765 (2011).

- Schmid D , LeitzmannMF. Association between physical activity and mortality among breast cancer and colorectal cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol.25(7), 1293–1311 (2014).

- Courneya KS , SegalRJ, McKenzieDCet al. Effects of exercise during adjuvant chemotherapy on breast cancer outcomes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.46(9), 1744–1751 (2014).

- Villarini A , PasanisiP, TrainaAet al. Lifestyle and breast cancer recurrences: the DIANA-5 trial. Tumori98(1), 1–18 (2012).

- Rack B , AndergassenU, NeugebauerJet al. The German SUCCESS C Study – the first European lifestyle study on breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel)5(6), 395–400 (2010).

- Rock CL , ByersTE, ColditzGAet al. Reducing breast cancer recurrence with weight loss, a vanguard trial: the exercise and nutrition to enhance recovery and good health for you (ENERGY) trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials34(2), 282–295 (2012).

- Travier N , Fonseca-NunesA, JavierreCet al. Effect of a diet and physical activity intervention on body weight and nutritional patterns in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors. Med. Oncol.31(1), 783 (2014).

- Calle EE , KaaksR. Overweight, obesity and cancer: epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Cancer4(8), 579–591 (2004).

- Patterson RE , RockCL, KerrJet al. Metabolism and breast cancer risk: frontiers in research and practice. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet.113(2), 288–296 (2013).

- Neilson HK , FriedenreichCM, BrocktonNT, MillikanRC. Physical activity and postmenopausal breast cancer: proposed biologic mechanisms and areas for future research. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.18(1), 11–27 (2009).

- Champ CE , VolekJS, SiglinJ, JinL, SimoneNL. Weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and breast cancer recurrence: are dietary recommendations supported by the data?Int. J. Breast Cancer doi:10.1155/2012/506868506868 (2012) ( Epub ahead of print).

- Lorincz AM , SukumarS. Molecular links between obesity and breast cancer. Endocr. Relat Cancer13(2), 279–292 (2006).

- McTiernan A , RajanKB, TworogerSSet al. Adiposity and sex hormones in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol.21(10), 1961–1966 (2003).

- Rock CL , FlattSW, LaughlinGAet al. Reproductive steroid hormones and recurrence-free survival in women with a history of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.17(3), 614–620 (2008).

- Rock CL , FlattSW, ThomsonCAet al. Effects of a high-fiber, low-fat diet intervention on serum concentrations of reproductive steroid hormones in women with a history of breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.22(12), 2379–2387 (2004).

- McTiernan A , WuL, ChenCet al. Relation of BMI and physical activity to sex hormones in postmenopausal women. Obesity (Silver Spring)14(9), 1662–1677 (2006).

- Pierce BL , Ballard-BarbashR, BernsteinLet al. Elevated biomarkers of inflammation are associated with reduced survival among breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol.27(21), 3437–3444 (2009).

- Nimmo MA , LeggateM, VianaJL, KingJA. The effect of physical activity on mediators of inflammation. Diabetes Obes. Metab15(Suppl. 3), 51–60 (2013).

- Allin KH , NordestgaardBG. Elevated C-reactive protein in the diagnosis, prognosis, and cause of cancer. Crit Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci.48(4), 155–170 (2011).

- Vona-Davis L , RoseDP. Angiogenesis, adipokines and breast cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.20(3), 193–201 (2009).

- Salgado R , JuniusS, BenoyIet al. Circulating interleukin-6 predicts survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer103(5), 642–646 (2003).

- Holloszy JO , FontanaL. Caloric restriction in humans. Exp. Gerontol.42(8), 709–712 (2007).

- Estruch R . Anti-inflammatory effects of the Mediterranean diet: the experience of the PREDIMED study. Proc. Nutr. Soc.69(3), 333–340 (2010).

- Gleeson M , BishopNC, StenselDJet al. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol.11(9), 607–615 (2011).

- Beavers KM , BrinkleyTE, NicklasBJ. Effect of exercise training on chronic inflammation. Clin. Chim. Acta411(11–12), 785–793 (2010).

- Lof M , BergstromK, WeiderpassE. Physical activity and biomarkers in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Maturitas73(2), 134–142 (2012).

- Schaffler A , ScholmerichJ, BuechlerC. Mechanisms of disease: adipokines and breast cancer – endocrine and paracrine mechanisms that connect adiposity and breast cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab.3(4), 345–354 (2007).

- Pollak MN , SchernhammerES, HankinsonSE. Insulin-like growth factors and neoplasia. Nat. Rev. Cancer4(7), 505–518 (2004).

- Goodwin PJ , EnnisM, PritchardKIet al. Fasting insulin and outcome in early-stage breast cancer: results of a prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol.20(1), 42–51 (2002).

- Erickson K , PattersonRE, FlattSWet al. Clinically defined type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.29(1), 54–60 (2011).

- Railo MJ , vonSK, PekonenF. The prognostic value of insulin-like growth factor-I in breast cancer patients. Results of a follow-up study on 126 patients. Eur. J. Cancer30A(3), 307–311 (1994).

- Turner BC , HafftyBG, NarayananLet al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor overexpression mediates cellular radioresistance and local breast cancer recurrence after lumpectomy and radiation. Cancer Res.57(15), 3079–3083 (1997).

- Fairey AS , CourneyaKS, FieldCJet al. Effects of exercise training on fasting insulin, insulin resistance, insulin-like growth factors, and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.12(8), 721–727 (2003).

- Djuric Z , DiLauraNM, JenkinsIet al. Combining weight-loss counseling with the weight watchers plan for obese breast cancer survivors. Obes. Res.10(7), 657–665 (2002).

- Befort CA , KlempJR, AustinHLet al. Outcomes of a weight loss intervention among rural breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat.132(2), 631–639 (2012).

- Thomson CA , StopeckAT, BeaJWet al. Changes in body weight and metabolic indexes in overweight breast cancer survivors enrolled in a randomized trial of low-fat vs. reduced carbohydrate diets. Nutr. Cancer62(8), 1142–1152 (2010).

- Goodwin PJ , SegalRJ, VallisMet al. Randomized trial of a telephone-based weight loss intervention in postmenopausal women with breast cancer receiving letrozole: the LISA trial. J. Clin. Oncol.32(21), 2231–2239 (2014).

- Emond JA , PierceJP, NatarajanLet al. Risk of breast cancer recurrence associated with carbohydrate intake and tissue expression of IGF-1 receptor. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev.23(7), 1273–1279 (2014).

- Hession M , RollandC, KulkarniU, WiseA, BroomJ. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat/low-calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities. Obes. Rev.10(1), 36–50 (2009).

- Westman EC , YancyWS, EdmanJS, TomlinKF, PerkinsCE. Effect of 6-month adherence to a very low carbohydrate diet program. Am. J. Med.113(1), 30–36 (2002).

- Keogh JB , BrinkworthGD, NoakesMet al. Effects of weight loss from a very-low-carbohydrate diet on endothelial function and markers of cardiovascular disease risk in subjects with abdominal obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.87(3), 567–576 (2008).

- Gannon MC , NuttallFQ. Effect of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet on blood glucose control in people with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes53(9), 2375–2382 (2004).

- Gonzalez-Vallinas M , Gonzalez-CastejonM, Rodriguez-CasadoA, Ramirez deMA. Dietary phytochemicals in cancer prevention and therapy: a complementary approach with promising perspectives. Nutr. Rev.71(9), 585–599 (2013).

- Rock CL , DoyleC, Demark-WahnefriedWet al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J. Clin.62(4), 243–274 (2012).

- Schmitz KH , CourneyaKS, MatthewsCet al. American college of sports medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.42(7), 1409–1426 (2010).

- Troiano RP . Can there be a single best measure of reported physical activity?Am. J. Clin. Nutr.89(3), 736–737 (2009).

- Mendez MA , WynterS, WilksR, ForresterT. Under- and overreporting of energy is related to obesity, lifestyle factors and food group intakes in Jamaican adults. Public Health Nutr.7(1), 9–19 (2004).

- Alfano CM , DayJM, KatzMLet al. Exercise and dietary change after diagnosis and cancer-related symptoms in long-term survivors of breast cancer: CALGB 79804. Psychooncology18(2), 128–133 (2009).