SUMMARY

This paper will present the multiple roles and the impact of cancer advocates. The emerging literature provides evidence for the consideration and integration of African–American breast cancer survivors as advocates in practice, policy and research relevant to cancer prevention and control. We present a practical outline for organizational assessment for the inclusion of advocates in these arenas. This assessment can be conducted by all levels of partners, including community advocacy and scientific organizations.

• African–Americans experience multiple barriers and challenges that lead to breast cancer survival and survivorship vulnerabilities.

• Given the persistence and scope and of these problems, innovative, multilevel strategies that embrace multisectoral representation, including researchers and advocates from various disciplines and sectors, are warranted.

• Advocacy is the focused actions and work of supporters from various walks of life, including cancer survivors and their loved ones, civil society organizations, clinicians and researchers.

• Cancer advocates can have a far-reaching impact, influencing key players at multiple levels to improve cancer prevention and control with the aim of improving patient health outcomes.

• Self-advocacy is carried out as the cancer survivor participates as an active, engaged member of the healthcare team.

• Greater self-advocacy results in improved quality of care, better psychosocial adjustment and adaptation to cancer and an enhanced overall survivorship experience.

• Community advocacy refers to the actions of individuals and organizations on behalf of cancer patients, survivors and caregivers.

• At the national level, cancer advocates are integral in shaping initiatives, policies and legislation to improve public health and healthcare systems as well as influencing funding decisions.

• African–American breast cancer survivors may have unique support and advocacy needs.

• The use of narratives and stories can establish personal and collective priorities, ultimately helping to define the state of affairs with regard to the cancer burden in the African–American community.

• There is a growing demand for community-engaged research, which embodies the equitable engagement of communities in all aspects of the research process.

• Advocacy is an important output of community-engaged research, as it positions community members, equipped with scientific knowledge, to advocate on their own behalf.

• We present a practical outline for advocates and researchers to achieve their goals and aims.

• To most aggressively combat breast health disparities, the work of researchers must be informed by the voices of community members.

• Breast cancer survivor advocates can galvanize effective breast cancer control among African–Americans, resulting in improved healthcare and health status in this vulnerable population.

African–Americans & breast cancer inequity

According to American Cancer Society estimates, the number of new breast cancer (BC) cases among African–Americans increased dramatically from 19,540 in 2009 [Citation1] to 27,060 in 2013 [Citation2], indicating that women in this group will be increasingly represented among the growing number of BC survivors. African–Americans are more likely to succumb to cancer-related death than any other ethnic group [Citation3] and bear a disproportionate burden of BC, with significant late-stage diagnoses, premenopausal onset, aggressive neoplasms and complex tumor histologic characteristics (i.e., estrogen-, progesterone-, and HER2-negative) [Citation4]. Furthermore, African–American women are among the most medically underserved, often with less access to quality care and worse health outcomes [Citation2,Citation5,Citation6,Citation2]. The existing surveillance, diagnostic and access to care barriers, as well as poorer prognostic characteristics and medical care, and significant co-occurring chronic illnesses and socio-ecological stressors of African–Americans lead to breast cancer survival and survivorship vulnerabilities [Citation6,Citation7].

In examining patient-reported outcomes, African–American breast cancer survivors (BCS) report significant physical, functional and social well-being challenges and psychological difficulties [Citation5,Citation8,Citation10,Citation5]. Factors contributing to these challenges are multifaceted and contextual [Citation9]. However, publications elucidating strategies to address the undue burden of BC among African–American women are limited [Citation10,Citation11]. Given the persistence and scope of the problem of unfavorable outcomes among African–American BCS, innovative, multilevel strategies that include multisectoral representation are warranted [Citation10,Citation12]. Hence, engaging diverse stakeholders, including BC survivors representing their communities, must be considered as central to the solution toward eradicating BC disparities [Citation13–16]. The aim of this paper is to present a brief, yet overarching overview of the relevance and potential impact of engaging and partnering with African–American BC advocates in advancing the future of cancer prevention and control for this particularly vulnerable population. We emphasize the roles of advocates in the research and health policy arenas to facilitate and enhance the responsiveness, applicability and benefit of policy priorities and strategies, and scientific advancements to relieve the undue burden of BC in our African–American community.

Cancer advocacy & the health of the public

The term advocacy refers to the focused actions and work of supporters from various walks of life, aiming to influence public policy and resource allocation decisions within political, economic and social systems and institutions for the benefit of an underserved group or vulnerable population [Citation17]. Historically, advocates have been the driving force behind pivotal public health campaigns [Citation18]. The past two decades, in particular, have brought about the formation of national and local advocacy organizations with wide variability in size and scope. Independently and as a collective, these advocacy groups have been particularly successful at raising public and political awareness, calling attention to improved standards and accountability for quality care and policies and elevating BC as the eminent public health priority for women in the USA [Citation19,Citation20].

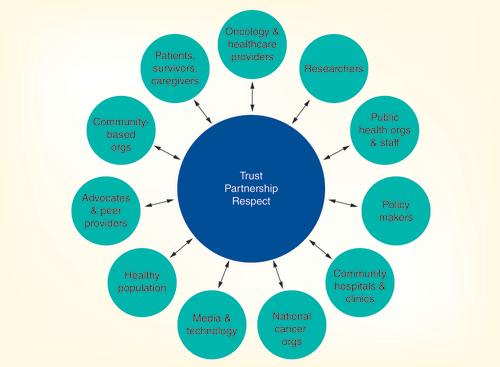

Self-advocacy, community advocacy and public interest advocacy represent the key components of the advocacy continuum [Citation21]. In concert with the evolving needs of the patient and the public health impact of BC, the role of advocacy may evolve from functioning at the individual level (e.g., cancer patients and caregivers) to operating at the community (e.g., cancer support groups, patient advocacy organizations [PAOs]) and systemic (national cancer advocacy organizations [CAOs]) levels [Citation22]. Therefore, cancer advocates can have a far-reaching impact, influencing key players at multiple levels to improve cancer prevention and control with a special emphasis on improving patient health outcomes [Citation23].

Self-advocacy

Self-advocacy is carried out as the cancer survivor joins and maintains an integral role as an active member of the healthcare team. Self-advocacy requires patient education and activation, such that the understanding of diagnosis, treatment options, treatments received and potential treatment side effects lead to effective disease self-management and patient–provider communication and shared medical decision-making [Citation24,Citation25]. In addition, self-advocating survivors are well acquainted with follow-up care recommendations, health advisories (e.g., healthy lifestyle practices) and strategies for improving quality of life. Greater self-advocacy results in improved quality of care [Citation26], better psychosocial adjustment and adaptation to cancer and an enhanced overall survivorship experience [Citation25,Citation27].

Cancer care education and self-advocacy skills sets can enable cancer survivors to overcome unique barriers (e.g., discrimination and stigmatization) [Citation28], fostering self-care, symptom management and coping [Citation29]. However, the effectiveness of self-advocacy depends greatly upon the survivor’s level of empowerment [Citation21] and is affected by various factors, including personal characteristics and technical skills, the complexity of the patient’s illness [Citation28,Citation30,Citation32,Citation28], and availability and utilization of various forms of support [Citation27]. Therefore, in addition to self-advocacy education and training, some cancer patients and survivors may benefit from broader empowerment strategies and support. This support may entail implementation of survivorship care plans [Citation11,Citation31], peer support [Citation21,Citation32] and professional counseling and navigation [Citation33] to direct patients to survivorship resources and to help them navigate through an increasingly complicated and costly healthcare system [Citation34]. A fully activated self-advocate is often savvy about resources related to research engagement and participation to increase the potential personal benefit, but more often to increase the voice of other affected persons to enhance their benefit from scientific advancement.

Community advocacy: ‘Advocacy for others’

Community advocacy refers to the actions of individuals and organizations on behalf of cancer patients, survivors and caregivers [Citation35,Citation36]. Advocates at the community level include patients, family members, friends and caregivers, as well as healthcare professionals and researchers [Citation25]. In the healthcare arena, many hospitals and organizations have developed patient advocacy programs, with nurses, social workers, patient navigators and lay community members carrying out the advocacy role to improve patient-oriented outcomes (e.g., health literacy, clinical research participation rates and survival rates) [Citation37,Citation38].

• Need for increased BC advocacy in the African–American community

African–American BCS may have unique support and advocacy needs [Citation10,Citation13,Citation39]. For example, there are data documenting that African–American women are not adequately educated about the benefit of appropriate surveillance [Citation40] and the impact of timely diagnostic, therapeutic care and follow-up care [Citation41]. In a study of the unmet needs of African–American BCS [Citation13], it was determined that, although African–American BCS were satisfied with their cancer treatment, they reported that their physicians did not provide sufficient disease/treatment information, discuss clinical trials participation, or refer them to BC support services.

African–American BCS value culturally informed emotional support services tailored to their individual needs [Citation11] and express the importance of peer-based support groups to provide multilevel functions, including emotional, social, spiritual, informational and financial support [Citation42]. The use of narratives and stories can establish personal and collective priorities, ultimately helping to define the state of affairs with regard to the cancer burden in the African–American community. Ashing-Giwa et al. [Citation42] suggest that advocacy challenges and transforms the secrecy, or ‘taboo,’ surrounding cancer among African–Americans. Their paper also highlights the importance of sharing family history to motivate others toward health-promoting practices and understanding familial and genetic vulnerability to improve risk reduction and appropriate surveillance, as well as the need for BCS to help change the community’s perceptions to reduce the stigma associated with BC.

National advocacy: ‘Public interest advocacy’

• Advocacy for policy

At the national level, cancer advocates are integral in shaping initiatives, policies and legislation to improve public health and healthcare systems [Citation31,Citation43], as well as influencing funding decisions (e.g., increasing training and education for minority health professionals) [Citation44–46]. BC policy advocacy includes: advancing breast health and cancer care policy at the state and federal levels; building leadership at various levels to bring about equity in BC outcomes; engaging researchers, clinicians, educators and survivors in ongoing dialogue to identify strategies for addressing breast health disparities; working collectively in multilevel coalitions to raise awareness of BC issues; and supporting community organizations in identifying and implementing effective interventions to reduce BC disparities.

African–American BC advocates are needed to represent their communities at the local and national levels. African–American BC advocacy organizations, including Sisters Network, Inc. [Citation47], Black Women’s Health Imperative [Citation48], African American Breast Cancer Alliance [Citation49] and African American Breast Cancer Coalition have directed their efforts and energies in presenting the experience and voice of African–American BC survivors and community to inform health policies and clinical practice. However, there are notable gaps in the tangible capital (i.e., finances), and social capital (i.e., influence and prominence) of ethnic minority advocacy organizations at the national level [Citation50]. These system and resource level disparities present important opportunities to for supporting and bi-directional learning, training and partnering with African–American BC advocates to better inform and advance the future of cancer prevention and control for this particularly vulnerable population. The inclusion of advocates in the health policy arenas may facilitate and enhance the responsiveness, applicability and benefit of policy priorities and strategies for the intended community.

• Advocacy for funding & research

Cancer research provides a scientific evidence base regarding the cancer landscape and burden, to inform health policy and public health decision-making. BC advocates and CAOs have a key role in shaping, securing and distributing funding for BC programs and research through their ability to cultivate and maintain relationships with donors and volunteers, corporate sponsors and political leaders [Citation51]. In addition, advocates are instrumental in raising public awareness about the community impact of cancer and partnering with medical experts and researchers to set forth new research questions, novel approaches, and public dissemination of findings that inform and motivate political leaders to support the advancement of cancer research [Citation52,Citation53]. Moreover, advocates can contribute to improving data collection; increasing minority participation in health research including clinical trials, biospecimen studies, and behavioral and survivorship research; and disseminating research findings to the public; thus, accelerating the translation research into practice [Citation54] for greater community benefit.

• The role of advocates in community-engaged research

There is a growing demand for community-engaged research (CER), which embodies the equitable engagement of communities in all aspects of the research process. At the heart of the CER model is partnership between the community being served and other stakeholders, including, advocates, researchers and funding agencies [Citation55,Citation56]. Each partner is empowered through bi-directional learning, and equipped with the necessary tools to implement changes and to document the efforts, successes, and lessons learned. Thus, carefully executed CER benefits both researchers and the community under study by targeting the appropriate health determinants [Citation57], enables the translation of science into practice [Citation10,Citation58] and, hence, addresses health disparities [Citation55,Citation59].

Advocacy is an important output of CER, as the exchange of information among community and academic partners positions community members, equipped with scientific knowledge, to advocate on their own behalf [Citation60]. In the context of CER, advocates can help to publicize knowledge gained from culturally and community responsive research, informing the community-at-large and health policy-makers [Citation61]. The Institute of Medicine has acknowledged the critical role of advocacy and community ownership in the effective translation of research findings into interventions that improve health outcomes [Citation62]. Ashing-Giwa et al. (2012) applied the CER concept to a study exploring the impact of peer-led (community-based) support groups on psychosocial care among African–American BCS [Citation42]. The support group curricula emphasized community engagement in advocacy activities. Participants in the support groups expressed that, given the relative dearth of information and resources specific to BC in African–American women, involvement of African–American BCS in the advocacy movement is essential to getting the attention and services they need. One support group participant offered a provocative statement: “I couldn’t find information on African–American women 5 years ago, that’s why I started working with American Cancer Society; if we don’t make them aware of us they won’t have anything to report.”

Developing an advocacy action plan to bring breast cancer equity

The following outline is a practical tool that may be used by researchers and advocates to facilitate the accomplishment of their research goals:

• Define the state of affairs and the burden: use data, narratives and personal stories to establish priority needs and concerns for self and others (e.g., community and country);

• Overall goal identification and establishment of aims: how will advocacy address stated priority(ies)? How will aims achieve the goal and make progress toward addressing priority(ies)?;

• Audience identification: who is the target audience(s)? What strategies and actions are needed to achieve the aims and goals? Identify short-, medium- and long-term activities;

• Internal capacity identification: who within the organization can lead the implementation of each strategy or activity? Succession planning processes can align leadership with aims and goals;

• Partner/collaborator identification: determine supporters, contributors and champions of the cause. Think broadly, in terms of varied resources, technical support, funding, location and personnel, among others;

• Timeline establishment: how long will each strategy take from planning, to implementation and evaluation?;

• Costs establishment: determining the cost of the programmatic and overall advocacy plan. Consider short, medium and long-term activities;

• Development of monitoring, evaluation, dissemination and sustainability plans: establish these early and create an opportunity for continuous monitoring and evaluation with rapid response change considerations, so that there are no ties to strategies or partner(s) who are not advancing priorities. What are lessons learned and progress toward goal(s) and aims? How can lessons learned, strategies, and approaches be shared for the greater good?

Conclusion

Cancer has a very powerful human side. Fear, anxiety, depression, beleaguerment and exasperation are common emotional responses among cancer patients and their family members. The intensity, pervasiveness and protractedness of the cancer experience can result in an enduring and profound life impact. Vulnerable groups, including African–Americans, are in urgent need of broad and targeted advocacy for greater BC prevention, control and care and improved survivorship and quality of life.

As cancer is fast becoming a primary cause of morbidity and mortality in the USA, we must accelerate research that can curtail cancer’s devastation, especially among our most vulnerable survivors. Toward this aim, research must include underrepresented groups as participants; community-based health organizations and peer-based support groups are crucial to accomplishing this task. The convincing justification for the inclusion of grass-roots advocates lies in their unique strengths of their community identities and commonality with their peers. They are culturally consonant, peer-based and responsive to cancer-related and personal needs, and their contribution expands our paradigm of supportive care. Thus, these groups extend the net of care to underserved cancer survivors. Moreover, the inherent, fundamental socio-ecological embeddedness of peer-based services seems to cultivate fertile ground for members’ personal development, empowerment, and sense of purpose. This purposefulness may readily translate into advocacy action for community benefit.

Advocacy involves the focused actions of individuals from various walks of life, including cancer survivors and their loved ones, civil society organizations, clinicians and researchers, and aims to influence public policy and resource allocation decisions within political, economic and social systems and institutions for the benefit of an underserved group or vulnerable population [Citation17]. Cancer advocates take an active role as informed, credible champions who promote prevention, timely detection, quality treatment and improved quality of life for those affected by cancer. We acknowledge, however, while the passion and enthusiasm of many breast cancer advocates are essential elements to powerful and effective advocacy, their work must be informed by evidence and presented in a balanced manner, approaching health promotion from a holistic and contextual perspective.

Ultimately, cancer advocacy is about changing minds and driving policy, practice, social and funding progress toward the betterment of those affected by this disease. The scarcity of resources and services that are culturally salient for African–Americans, along with the growing number of African–American patients suffering with cancer, makes a compelling call for their inclusion in advocacy efforts toward building cancer prevention and control systems and a healthcare system that is responsive to these communities, in order to reduce cancer disparities and bring about health equity. There is a tremendous need to train new advocates to catalyze and strengthen these efforts.

The potential for survivor and civil society advocacy activities is broad and can include prevention education, screening programs, patient navigation, policy involvement, funding allocation and research engagement. In addition, a practical, community-engaged approach in cancer prevention, control, medical care and the psychosocial net of care is necessary and urgent. However, more studies of broad advocacy inclusion are needed to further examine their efficacy, sustainability and cost-effectiveness before such approaches are widely accepted and implemented.

Future perspective: the role of advocacy in paving the way for health equity

We have emphasized the important role of African–American BCS in community-engaged research. Community-engaged research facilitates a sense of ownership and enhanced community capacity, especially among the underserved. In order to most aggressively combat breast health disparities, the work of researchers must be informed by the voices of community members. BCS are uniquely positioned to represent their own communities as partners in research projects and will be instrumental in understanding the needs and priorities of the community, defining the research questions and study designs, implementing the studies and disseminating the research results. As such, BC survivor advocates can galvanize effective BC control among African–Americans, resulting in improved healthcare and health status in this vulnerable population [Citation11,Citation39].

As we make tremendous strides in biomedical research and treatment advancements, we see persistent BC disparities and, perhaps, even a widening of the gaps in health status and outcomes between racial/ethnic groups. Thus, there is a critical call to action for inclusion of African–American BC survivors in advocacy efforts that are most current and salient to the African–American community. In particular, these women must contribute to the emerging research agenda, including assessment of genetic determinants as well as epigenetic factors such as environmental exposures (e.g., increased air pollution in urban regions; early and long-term use of hair products containing flame retardants and other potential carcinogens) and socio-ecological contexts (e.g., neighborhood segregation; healthcare discrimination and marginalization), and behavior-related factors (e.g., sedentary lifestyle, food choices and adiposity), which may increase the BC burden and mortality among African–American survivors. Furthermore, in the age of the Affordable Care Act, quality care and care accountability are paramount and measurable, providing further opportunity for African–American survivor advocates to join forces with other stakeholders to help bring about equitable care and health outcomes ().

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This paper is informed by the work of the African American Breast Cancer Coalition (AABCC) led by RH Santifer, KMcDowell, E Mitchell, V Martin, P Clark and the African Caribbean Cancer Consortium (AC3) led by C Ragin. Funding provided by the Excellence Award, City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center awarded to KT Ashing and a Charles R Drew University Women’s Health Collaborative Grant awarded to KT Ashing. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2009–2010.American Cancer Society, Inc., Atlanta, GA, USA (2009). www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/cffaa20092010pdf.pdf

- American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2013–2014.American Cancer Society, Inc., Atlanta, GA, USA (2013). www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-036921.pdf

- American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2014.American Cancer Society, Inc., Atlanta, GA, USA (2014). www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/webcontent/acspc-042151.pdf

- Desantis C , MaJ, BryanL, JemalA. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J. Clin.64(1), 52–62 (2014).

- Siegel R , DesantisC, VirgoKet al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin.62(4), 220–241 (2012).

- Lechner SC , Ennis-WhiteheadN, RobertsonBRet al. Adaptation of a psycho-oncology intervention for black breast cancer survivors: project CARE. Couns. Psychol.41(2), 286–312 (2013).

- Matthews AK , TejedaS, JohnsonTP, BerbaumML, ManfrediC. Correlates of quality of life among African American and white cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs.35(5), 355 (2012).

- Ashing-Giwa KT , TejeroJS, KimJ, PadillaGV, HellemannG. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Qual. Life Res.16(3), 413–428 (2007).

- Wu AH , GomezSL, VigenCet al. The California Breast Cancer Survivorship Consortium (CBCSC): prognostic factors associated with racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer survival. Cancer Causes Control24(10), 1821–1836 (2013).

- Mollica M , NewmanSD. Breast cancer in African Americans: from patient to survivor. J. Transcult. Nurs.25(4), 334–340 (2014).

- Ashing-Giwa K , TappC, BrownSet al. Are survivorship care plans responsive to African–American breast cancer survivors? Voices of survivors and advocates. J. Cancer Surviv.7(3), 283–291 (2013).

- Meade CD , MenardJM, LuqueJS, Martinez-TysonD, GwedeCK. Creating community-academic partnerships for cancer disparities research and health promotion. Health Promot. Pract.12(3), 456–462 (2011).

- Von Friederichs-Fitzwater MM , DenyseRT. The unmet needs of African American women with breast cancer. Adv. Breast Cancer Res.1, 1 (2012).

- Ashing-Giwa KT , PadillaG, TejeroJet al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psychooncology13(6), 408–428 (2004).

- Jones CE , MabenJ, JackRHet al. A systematic review of barriers to early presentation and diagnosis with breast cancer among black women. BMJ Open4(2), e004076 (2014).

- Yoo GJ , LevineEG, PasickR. Breast cancer and coping among women of color: a systematic review of the literature. Support. Care Cancer22(3), 811–824 (2014).

- Almog-Bar M , SchmidH. Advocacy activities of nonprofit human service organizations a critical review. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q.43(1), 11–35 (2014).

- Rayner G , LangT. Ecological Public Health: Reshaping the Conditions for Good Health.Routledge, London, UK (2013).

- Bell K . The breast-cancer-ization of cancer survivorship: implications for experiences of the disease. Soc. Sci. Med.110, 56–63 (2014).

- Hassett MJ , McNiffKK, DickerAPet al. High-priority topics for cancer quality measure development: Results of the 2012 American Society of Clinical Oncology Collaborative Cancer Measure Summit. J. Oncol. Pract.10(3), e160–e166 (2014).

- Hoffman B , StovallE. Survivorship perspectives and advocacy. J. Clin. Oncol.24(32), 5154–5159 (2006).

- Stovall EL . Cancer advocacy. In: Cancer Survivorship.GanzPA ( Ed.). Springer, NY, USA, 283–286 (2007).

- Gorin SS , BadrH, KrebsP, DasIP. Multilevel interventions and racial/ethnic health disparities. J. Natl Cancer Inst.2012(44), 100–111 (2012).

- Fiscella K , RansomS, Jean-PierrePet al. Patient-reported outcome measures suitable to assessment of patient navigation. Cancer117(S15), 3601–3615 (2011).

- National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship . The Cancer Advocacy Continuum (2006). www.canceradvocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/2006-annual-report.pdf

- Burg MA , ZebrackB, WalshKet al. Barriers to accessing quality health care for cancer patients: a survey of members of the association of oncology social work. Soc. Work Health Care49(1), 38–52 (2010).

- Hagan TL , DonovanHS. Self-advocacy and cancer: a concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs.69(10), 2348–2359 (2013).

- Wiltshire J , CroninK, SartoGE, BrownR. Self-advocacy during the medical encounter: use of health information and racial/ethnic differences. Med. Care44(2), 100–109 (2006).

- McCorkle R , ErcolanoE, LazenbyMet al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J. Clin.61(1), 50–62 (2011).

- Anthony JS . Self-advocacy in health care decision-making among elderly African Americans. J. Cult. Divers.14(2), 88–95 (2007).

- McCabe MS , BhatiaS, OeffingerKCet al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J. Clin. Oncol.31(5), 631–640 (2013).

- Lim J , BaikOM, Ashing-GiwaKT. Cultural health beliefs and health behaviors in Asian American breast cancer survivors: a mixed-methods approach. Oncol. Nurse. Forum39, 388–397 (2012).

- Volker DL , BeckerH, KangSJ, KullbergV. A double whammy: health promotion among cancer survivors with preexisting functional limitations. Oncol. Nurs. Forum40(1), 64–71 (2013).

- Sesto M , TevaarwerkA, WiegmannD. Human factors engineering: targeting systems for change. In: Health Services for Cancer Survivors, FeuersteinM, GanzPA ( Eds). Springer, NY, USA, 329–352 (2011).

- Hewitt M , GreenfieldS, StovallE. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition.National Academies Press, DC, USA (2005).

- Rivera-Colón V , RamosR, DavisJLet al. Empowering underserved populations through cancer prevention and early detection. J. Community Health38(6), 1067–1073 (2013).

- Hall-Long B . Nurse matters: assuming your role in advocacy. Home Healthc. Nurs.28(5), 309–316 (2010).

- Meade CD , WellsKJ, ArevaloMet al. Lay navigator models for impacting cancer health disparities. J. Cancer Educ.29, 449–457 (2014).

- Wells, AA, Gulbas, L, Sanders-Thompson, V. Shon, E-JKreuter, MW African–American breast cancer survivors participating in a breast cancer support group: translating research into practice. J. Canc Educ.29, 619–625 (2014).

- Advani PS , YingJ, TheriaultRet al. Ethnic disparities in adherence to breast cancer survivorship surveillance care. Cancer120(6), 894–900 (2014).

- Ashing-Giwa KT , GonzalezP, LimJWet al. Diagnostic and therapeutic delays among a multiethnic sample of breast and cervical cancer survivors. Cancer116(13), 3195–3204 (2010).

- Ashing-Giwa K , TappC, RosalesMet al. Peer-based models of supportive care: the impact of peer support groups in African American breast cancer survivors. Oncol. Nurs. Forum39(6), 585–591 (2012).

- Gregg G . Psychosocial issues facing African and African American women diagnosed with breast cancer. Soc. Work Public Health24(1–2), 100–116 (2009).

- Keller AC , PackelL. Going for the cure: patient interest groups and health advocacy in the United States. J. Health Polit. Policy Law, 39(2), 331–367 (2013).

- Bliss K . Role of advocacy in health care reform: literature review and call to action. Am. J. Health Stud.28(2), 41–49 (2013).

- Best RK . Disease politics and medical research funding three ways advocacy shapes policy. Amer. Soc. Rev.77(5), 780–803 (2012).

- Sisters Network, Inc. www.sistersnetworkinc.org/

- Black Womens Health Imperative . www.bwhi.org/

- African American Breast Cancer Alliance (AABCA) . http://aabcainc.org/

- Andrews C . Unintended consequences: Medicaid expansion and racial inequality in access to health insurance. Health Soc. Work39(3), 131–133 (2014).

- Weberling B . Framing breast cancer: building an agenda through online advocacy and fundraising. Public Relat. Rev.38(1), 108–115 (2012).

- Perlmutter J , BellSK, DarienG. Cancer research advocacy: past, present, and future. Cancer Res.73(15), 4611–4615 (2013).

- Printz C . Survivors advocate for cancer research and patients: these advocates offer a unique perspective when communicating with lawmakers, care providers, and the scientific community. Cancer118(6), 1471–1473 (2012).

- Simon M , RivaE, BerganRet al. Improving diversity in cancer research trials: the story of the cancer disparities research network. J. Canc. Educ.29(2), 366–374 (2014).

- Rodgers KC , AkintobiT, ThompsonWW, EvansD, EscofferyC, KeglerMC. A model for strengthening collaborative research capacity illustrations from the Atlanta clinical translational science institute. Health Educ. Behav.41(3), 267–274 (2013).

- Michener L , CookJ, AhmedSM, YonasMA, Coyne-BeasleyT, Aguilar-GaxiolaS. Aligning the goals of community-engaged research: why and how academic health centers can successfully engage with communities to improve health. Acad. Med.87(3), 285 (2012).

- Wallerstein NB , YenIH, SymeSL. Integration of social epidemiology and community-engaged interventions to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health101(5), 822 (2011).

- Osuch JR , SilkK, PriceCet al. A historical perspective on breast cancer activism in the United States: from education and support to partnership in scientific research. J. Womens Health21(3), 355–362 (2012).

- Sabo S , IngramM, ReinschmidtKMet al. Predictors and a framework for fostering community advocacy as a community health worker core function to eliminate health disparities. Am. J. Public Health103(7), e67–e73 (2013).

- Brown P , Morello-FroschR, BrodyJGet al. Institutional review board challenges related to community-based participatory research on human exposure to environmental toxins: a case study. J. Environ. Health9(1), 39 (2010).

- Cohen A , LopezA, MalloyN, Morello-FroschR. Our environment, our health: a community-based participatory environmental health survey in Richmond, California. Health Educ. Behav.39(2), 198–209 (2012).

- Hicks S , DuranB, WallersteinNet al. Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Prog. Community Health Partnersh.6(3), 289 (2012).