Abstract

Background: We examined characteristics of early-onset colorectal cancer (CRC) patients to identified factors, which may lead to earlier diagnosis. Materials & methods: This is a retrospective study with inclusion criteria: CRC diagnosed between 2012 and 2018 and age at diagnosis <50 years. Results: A total of 209 patients were included (mean age 41.8 years). Of those patients 42.5% had rectal cancer and 37.8% were stage IV at initial diagnosis. Of patients with data available for rectal bleeding history (n = 173), 50.8% presented with rectal bleeding and median time from onset of bleeding to diagnosis was 180 days (interquartile range 60–365), with longer duration noted in advanced cancer. Conclusion: Prolonged rectal bleeding history was noted in a significant proportion of early-onset CRC patients, with longer duration of rectal bleeding noted in stage IV patients. Patients and primary care physicians should be made aware of this finding in order to facilitate timely referral for diagnostic workup.

In contrast with the older population, the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in early-onset patients (defined as less than 50 years of age at the time of CRC diagnosis) has been increasing over the last three decades [Citation1–5]. While the decreasing incidence of CRC in older adults in the United States is largely attributed to implementation of screening through colonoscopies and stool based tests [Citation1] in the 1990s, the precise etiology of rising incidence in early-onset patients is not entirely clear, but could conceivably be associated with increasing rate of obesity and changing dietary and environmental factors [Citation6–8]. Similar trends have been noticed across Europe and several other countries, although the rate of increasing incidence in not as dramatic [Citation9,Citation10]. It is also known that when compared with older patients, early-onset patients with CRC tend to have a higher proportion of left-sided tumors [Citation11], microsatellite instability (MSI) [Citation12], underlying hereditary syndromes [Citation13], exhibit specific molecular [Citation14,Citation15] and clinical characteristics associated with a distinct biologic phenotype (e.g., higher grade and mucinous or signet ring histology) [Citation16] and receive more aggressive treatment [Citation17]. Furthermore, younger patients tend to present at a more advanced stage [Citation18,Citation19], although there is conflicting data on survival when compared with stage matched older patients [Citation19–23]. Specifically in early-onset CRC patients, venous invasion [Citation24], signet-ring cell carcinoma, infiltrating tumor edges and aggressive histologic grade [Citation25] have been associated with poor prognosis. In a study from Denmark, compared with older patients, patients with early-onset CRC were shown to be more likely to present with abdominal pain, although a similar trend for hematochezia was seen only in patients with rectal cancer [Citation26]. However, other studies have reported similar rates and duration of symptoms in younger and older patients [Citation27,Citation28].

Given the increasing incidence of CRC in younger patients, in 2018, the American Cancer Society (ACS; NY, USA) made a qualified recommendation to decrease the age at which patients should start screening for CRC to age 45 and above [Citation29]. However, there is considerable variation in coverage by state and insurance provider, and screening for average risk individuals between the age 45 and 49 is not currently widely implemented. Unfortunately, even the age 45 cut off for screening will still miss a substantial proportion of early-onset CRCs. As a result, most early-onset patients are diagnosed after the onset of symptoms [Citation30], which may contribute to advanced stage at diagnosis compared with older patients. Understanding whether there is an association between duration of symptoms prior to presentation and stage at diagnosis in early-onset CRC patients could lead to implementation of timely diagnostic testing and less advanced cancer at diagnosis. In this study, we evaluate the association between onset of symptoms prior to diagnosis and stage at diagnosis and describe the characteristics of early-onset patients with CRC.

Materials & methods

Study design & patient population

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective observational study of all CRC patients available through the University of Colorado Cancer Center Registry (CO, USA) that were seen at the Anschutz medical campus in Aurora, Colorado. CRC was defined as any cancer that originated in colon or rectum and we included the following histology – adenocarcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, signet cell and carcinoma undifferentiated not otherwise specified. Right sided colon cancer was defined as cancer originating from the cecum to the right flexure; left sided colon cancer was defined as cancer originating from left flexure to the sigmoid colon; while cancer originating in the transverse colon was defined as transverse colon cancer. The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer between the years 2012 and 2018 and age at diagnosis of less than 50 years. Rectal bleeding was defined as ‘bleeding per rectum’ and was obtained from electronic medical records in the history of presenting illness section. Family history of any cancer in first and second degree relatives was obtained from the cancer registry. We chose 50 years as the age cutoff to define early-onset CRC as multiple professional societies [Citation31–33] recommend starting CRC screening at age 50. Pertinent data including baseline characteristics, clinical presentation, family history, pathology, molecular testing and staging were collected.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as mean (standard deviation) and median (range), while categorical variables were reported as frequency (percentage). The duration of rectal bleeding prior to diagnosis was stratified by American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition 2017 staging at diagnosis [Citation34]. The Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to determine if there were any statistically significant difference in duration of rectal bleeding across all four stage groups and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare stage I to stage IV. All tests were 2 sided, with an alpha level set at 0.05 for statistical significance. The data collected were analyzed using the Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP.

Results

Baseline characteristics

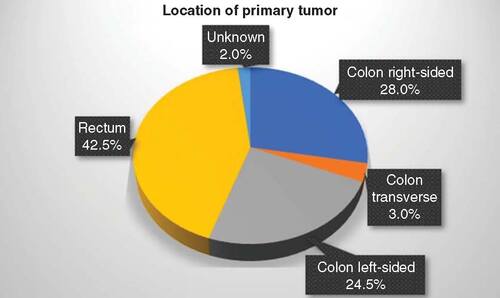

A total of 209 patients with early-onset CRC were available for review and the baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in . Mean age at diagnosis was 41.8 ± 6.5 years and 55.9% were males. 42.5% had rectal cancer and a majority of the CRC diagnoses had left-sided tumors (67.0%), which includes both rectal cancer and left sided colon cancer. 24.0% of the CRCs were left-sided colon and 28.0% were right-sided, while 3.0% of patients had transverse colon cancer, as demonstrated in . 89.4% were adenocarcinomas and 14.8% were tumor differentiation grade 3. At diagnosis, the mean body mass index was 26.6 ± 5.7 and the mean carcinoembryonic antigen was 135.5 ± 749.4 ng/ml. A total of 72.7% had a family history of any cancer. MSI instability status was known in 174 patients, of whom 10.9% were MSI-High. Of the 135 patients with known RAS mutation status (NRAS or KRAS), 49.6% of patients had a RAS mutation. 3.9% of patients with known BRAF mutation status had a BRAF mutation. A total of 37.8% of early-onset CRC patients were stage IV at the time of initial diagnosis, while 32.0% were stage III, 17.2% were stage II and 8.1% stage I, as depicted in .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study population.

n = 209.

AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Reproduced with permission from [Citation34].

![Figure 2. American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition 2017 stage at diagnosis in the study population.n = 209.AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.Reproduced with permission from [Citation34].](/cms/asset/a0aa8bfc-6a12-4ec8-a6a9-38050dc0d04a/icrc_a_12323728_f0002.jpg)

Association of bleeding history with stage at diagnosis

Patients whose information regarding history of rectal bleeding was available (n = 173), 50.8% presented with rectal bleeding prior to diagnosis. Of those who presented with rectal bleeding (n = 88), the mean time from the onset of bleeding to diagnosis was 295 ± 327 days, with the median of 180 days (interquartile range 60–365). Among the 173 patients with available bleeding history information, 75 had rectal cancer and 118 had left-sided cancer (including rectal and left-sided colon cancers). Among these 173 patients, 61 out of 75 (81.3%) rectal cancer patients and 81 out of 118 (68.6%) with left-sided tumors, presented with rectal bleeding. In contrast, only 27 out of the 98 (27.5%) colon cancer patients and 6 out of the 55 (10.9%) of the right-sided tumors presented with rectal bleeding.

The duration of bleeding prior to diagnosis was significantly different across groups stratified by stage at diagnosis (p = 0.004; Kruskal–Wallis H test), with longer duration of bleeding noted for more advanced stage as shown in . Median duration of bleeding was 333.5 days for Stage IV patients, compared with 30 days for Stage I patients (p = 0.05; Mann–Whitney U test).

‘x’ represents the mean for the particular column.

AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Reproduced with permission from [Citation34].

![Figure 3. Duration of rectal bleeding prior to diagnosis stratified by American Joint committee on cancer 8th edition 2017 stage at diagnosis.‘x’ represents the mean for the particular column.AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer.Reproduced with permission from [Citation34].](/cms/asset/df075c99-1ca8-4318-bb18-33cfa8a048da/icrc_a_12323728_f0003.jpg)

Discussion

In this study we analyzed data of early-onset CRC patients from the University of Colorado Cancer Center registry and report three major findings: patients presented with prolonged rectal bleeding history prior to diagnosis; longer duration of bleeding was noted for patients with more advanced stage at diagnosis; and finally we confirmed prior reporting that early-onset CRC patients present at a higher stage.

The incidence of early-onset CRC has been increasing at a troubling rate over the last 3 decades [Citation1–5]. An analysis from the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) database showed that colon cancer incidence rates increased by 1–2.4% annually since the mid-1980s for adults 20–30 years and 0.5–1.3% since the mid-1990s in adults aged 40–54 years, with similar trends observed in other parts of the world [Citation23]. Even more alarming is the trend in rectal cancer incidence, which has been increasing even faster and for a longer period of time (3.2% annually since the 1970s in adults aged 20–29 years) [Citation1], although a diverging trend has been noticed in parts of Italy [Citation35]. This rising incidence of CRC in early-onset patients coinciding with declining rates of CRC in older adults has led to a dramatic shift in the age adjusted percentage of CRC in adults <55 years of age (11.6% during 1989–1990 to 16.6% during 2012–13 for colon cancers and from 14.6 to 29.2%, respectively, for rectal cancers) [Citation1].

The precise etiology and risk factors associated with the rising incidence of CRC in early-onset patients remain unknown and is an active area of investigation [Citation36]. Although lifestyle habits such as red meat consumption and sedentary lifestyle are known risk factors for CRC and the prevalence of such habits has dramatically increased over the past few decades in the United States [Citation37], their contribution to rising early-onset CRC incidence is not yet established [Citation6–8]. Hereditary genetic syndromes (e.g., familial adenomatous polyposis and Lynch syndrome [Citation38,Citation39]) and predisposing medical conditions (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease [Citation40]) account for a higher proportion of cases in early-onset CRC patients, however, that alone would not explain the increasing incidence of CRC in these patients as the percentage of patients with these conditions has remained relatively stable [Citation23]. Further population-based studies will need to be performed to elucidate the exact etiology of the increasing incidence of CRC in early-onset patients.

Given the increasing incidence of CRC in early-onset patients, in 2018, ACS made a qualified recommendation to decrease the age at which patients start screening for CRC from age 50 to age 45 [Citation29]. Retrospective data from colonoscopies performed in individuals age 40 to 49 years have shown similar rates of adenoma detection when compared with older adults, however, there is a lower rate of advanced neoplasia in younger patients [Citation23,Citation41]. Nevertheless, updated modeling adjusting for increasing early-onset CRC incidence indicated that initiating colonoscopy screening at age 45 (compared with age 50) increased life-years gained by 6.2% at the cost of 17.0% more colonoscopies per 1000 adults over an individual’s lifetime of screening. ACS’s recommendation does allow for other forms of screening such as radiographic and stool-based tests. This study lends support to this change in the screening guidelines. However, since the absolute risk of developing CRC in patients younger than 45 still remains relatively low (1:1200 for <40 years old compared with 1:25 for >70 years old) [Citation42], routine screening for patients under age 50 is still controversial and not endorsed by all professional societies [Citation31–33].

In the absence of screening for early-onset patients, other methods need to be pursued to avoid delays in diagnosis and lower the percentage of early-onset CRC patients diagnosed with advanced stage cancer. Some studies have shown that younger patients are more likely to present with abdominal pain and rectal bleeding [Citation26], although other studies have reported similar symptoms in older and younger patients [Citation27,Citation28]. It is known that younger patients tend to wait longer before seeking medical care and can experience further delay in diagnostic studies and initiation of treatment at the level of the healthcare system [Citation43]. Indeed, this may explain the prolonged duration of rectal bleeding history noted in our study. The delay could be related to lack of insurance or underinsurance in early-onset patients, low suspicion of underlying malignancy from both patients and healthcare providers and attribution of symptoms to more benign etiologies like hemorrhoids. In addition, it is conceivable that the longer duration of bleeding translates to late diagnosis, which subsequently allows more time for the cancer to spread both locally and distantly, leading to more advanced stage at diagnosis, as noted in our study. The predilection for left-sided and rectal tumors in early-onset CRC patients translates to symptoms such as rectal bleeding, rectal pain and abdominal pain [Citation44]. This in turn affords the opportunity to recognize these symptoms as concerning and initiate early investigation. Moreover, given the high proportion of left-sided tumors, flexible sigmoidoscopy could be a useful initial screening tool in early-onset patients when the suspicion is not high enough to warrant a colonoscopy. The findings of this study should promote increased awareness among the general public and primary care providers and should lead to early pursuit of aforementioned symptoms in otherwise young, low-risk patients, as these symptoms may represent an underlying colorectal malignancy.

Although our findings suggest an important link between duration of rectal bleeding and stage at presentation, we acknowledge the limitations of our study. Given the inherent retrospective nature and selection of patients, we cannot confirm a causal relationship between duration of symptoms and higher stage at diagnosis. Furthermore, patients seen at Anschutz Medical campus, which is a tertiary care medical center, are more likely to be referred from other medical centers, which increases their probability of having more advanced disease at the time of diagnosis. Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings yield important clinical implications.

Conclusion & future perspective

To conclude, this study found prolonged rectal bleeding history prior to diagnosis in a significant proportion of early-onset patients with CRC, with higher duration of bleeding noted in more advanced stage. Furthermore, we confirmed prior reporting that early-onset patients present at a higher stage. Patients and primary care physicians should be made aware of this finding in order to facilitate timely referral for diagnostic studies, which may lead to earlier diagnosis, less advanced disease at diagnosis and improved outcomes.

In contrast to the older population, the incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in early-onset patients (defined as age <50 years in this study) has been increasing over the last three decades, the precise etiology of which remains unclear.

In this study of early-onset CRC patients, we found that patients presented with prolonged rectal bleeding history (median 180 days) prior to diagnosis.

We also noted longer duration of bleeding in patients with more advanced stage at diagnosis.

Furthermore, we confirm prior reporting that early-onset CRC patients present at a higher stage.

Patients and primary care physicians should be made aware of these findings in order to facilitate timely referral for diagnostic studies, which may lead to earlier diagnosis, less advanced disease at diagnosis, and improved outcomes.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- SiegelRL, FedewaSA, AndersonWFet al.Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J. Natl Cancer Inst.109(8), djw322 (2017).

- AbdelsattarZM, WongSL, RegenbogenSE, JomaaDM, HardimanKM, HendrenS. Colorectal cancer outcomes and treatment patterns in patients too young for average-risk screening. Cancer122(6), 929–934 (2016).

- BaileyCE, HuCY, YouYNet al.Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975–2010. JAMA Surg.150(1), 17–22 (2015).

- JacobsD, ZhuR, LuoJet al.Defining early-onset colon and rectal cancers. Front. Oncol.8, 504 (2018).

- YouYN, XingY, FeigBW, ChangGJ, CormierJN. Young-onset colorectal cancer: is it time to pay attention?Arch. Intern. Med.172(3), 287–289 (2012).

- WolinKY, YanY, ColditzGA, LeeIM. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer100(4), 611–616 (2009).

- LarssonSC, WolkA. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Cancer119(11), 2657–2664 (2006).

- HofsethLJ, HebertJR, ChandaAet al.Early-onset colorectal cancer: initial clues and current views. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.17(6), 352–364 (2020).

- VuikFE, NieuwenburgSA, BardouMet al.Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in young adults in Europe over the last 25 years. Gut68(10), 1820–1826 (2019).

- SiegelRL, TorreLA, SoerjomataramIet al.Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence in young adults. Gut68(12), 2179–2185 (2019).

- SegevL, KaladyMF, ChurchJM. Left-sided dominance of early-onset colorectal cancers: a rationale for screening flexible sigmoidoscopy in the young. Dis. Colon Rectum61(8), 897–902 (2018).

- BolandCR, GoelA. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology138(6), 2073–2087e2073 (2010).

- MorkME, YouYN, YingJet al.High prevalence of hereditary cancer syndromes in adolescents and young adults with colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.33(31), 3544–3549 (2015).

- LieuCH, GolemisEA, SerebriiskiiIGet al.Comprehensive genomic landscapes in early and later onset colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.25(19), 5852–5858 (2019).

- SerebriiskiiIG, ConnellyC, FramptonGet al.Comprehensive characterization of RAS mutations in colon and rectal cancers in old and young patients. Nat. Commun.10(1), 3722 (2019).

- YeoH, BetelD, AbelsonJS, ZhengXE, YantissR, ShahMA. Early-onset colorectal cancer is distinct from traditional colorectal cancer. Clin. Colorectal Cancer16(4), 293–299.e296 (2017).

- QuahHM, JosephR, SchragDet al.Young age influences treatment but not outcome of colon cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol.14(10), 2759–2765 (2007).

- YouYN, DozoisEJ, BoardmanLA, AakreJ, HuebnerM, LarsonDW. Young-onset rectal cancer: presentation, pattern of care and long-term oncologic outcomes compared to a matched older-onset cohort. Ann. Surg. Oncol.18(9), 2469–2476 (2011).

- KasiPM, ShahjehanF, CochuytJJ, LiZ, ColibaseanuDT, MercheaA. Rising proportion of young individuals with rectal and colon cancer. Clin. Colorectal Cancer18(1), e87–e95 (2019).

- LieuCH, RenfroLA, DeGramont Aet al.Association of age with survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis from the ARCAD Clinical Trials Program. J. Clin. Oncol.32(27), 2975–2984 (2014).

- WangW, ChenW, LinJ, ShenQ, ZhouX, LinC. Incidence and characteristics of young-onset colorectal cancer in the United States: an analysis of SEER data collected from 1988 to 2013. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol.43(2), 208–215 (2019).

- ShidaD, AhikoY, TanabeTet al.Shorter survival in adolescent and young adult patients, compared to adult patients, with stage IV colorectal cancer in Japan. BMC Cancer18(1), 334 (2018).

- MauriG, Sartore-BianchiA, RussoAG, MarsoniS, BardelliA, SienaS. Early-onset colorectal cancer in young individuals. Mol. Oncol.13(2), 109–131 (2019).

- MakelaJT, KiviniemiH. Clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer in patients under 40 years of age. Int. J. Colorectal. Dis.25(7), 823–828 (2010).

- CusackJC, GiaccoGG, ClearyKet al.Survival factors in 186 patients younger than 40 years old with colorectal adenocarcinoma. J. Am. Coll. Surg.183(2), 105–112 (1996).

- FrostbergE, RahrHB. Clinical characteristics and a rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer in a nationwide cohort of 521 patients aged 18–40 years. Cancer Epidemiol.66, 101704 (2020).

- KarstenB, KimJ, KingJ, KumarRR. Characteristics of colorectal cancer in young patients at an urban county hospital. Am. Surg.74(10), 973–976 (2008).

- ChanKK, DassanayakeB, DeenRet al.Young patients with colorectal cancer have poor survival in the first twenty months after operation and predictable survival in the medium and long-term: analysis of survival and prognostic markers. World J. Surg. Oncol.8, 82 (2010).

- WolfAMD, FonthamETH, ChurchTRet al.Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J. Clin.68(4), 250–281 (2018).

- DozoisEJ, BoardmanLA, SuwanthanmaWet al.Young-onset colorectal cancer in patients with no known genetic predisposition: can we increase early recognition and improve outcome?Medicine (Baltimore)87(5), 259–263 (2008).

- ForceUSPST, Bibbins-DomingoK, GrossmanDCet al.Screening for colorectal cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA315(23), 2564–2575 (2016).

- RexDK, BolandCR, DominitzJAet al.Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology153(1), 307–323 (2017).

- Screening NCPGIOCC. (2019). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colorectal_screening.pdf

- AminMb ES, GreeneFlet al.et al. ( Eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual.Springer International Publishing, New York, 8 (2017).

- RussoAG, AndreanoA, Sartore-BianchiA, MauriG, DecarliA, SienaS. Increased incidence of colon cancer among individuals younger than 50 years: a 17 years analysis from the cancer registry of the municipality of Milan, Italy. Cancer Epidemiol.60, 134–140 (2019).

- DwyerAJ, MurphyCC, BolandCRet al.A summary of the fight colorectal cancer working meeting: exploring risk factors and etiology of sporadic early-age onset colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology157(2), 280–288 (2019).

- GuthrieJF, LinBH, FrazaoE. Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977–78 versus 1994–96: changes and consequences. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav.34(3), 140–150 (2002).

- PearlmanR, FrankelWL, SwansonBet al.Prevalence and spectrum of germline cancer susceptibility gene mutations among patients with early-onset colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol.3(4), 464–471 (2017).

- StoffelEM, KoeppeE, EverettJet al.Germline genetic features of young individuals with colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology154(4), 897–905e891 (2018).

- NadeemMS, KumarV, Al-AbbasiFA, KamalMA, AnwarF. Risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel diseases. Semin. Cancer Biol.doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.05.001 (2019) ( Epub ahead of print).

- RundleAG, LebwohlB, VogelR, LevineS, NeugutAI. Colonoscopic screening in average-risk individuals ages 40 to 49 vs 50 to 59 years. Gastroenterology134(5), 1311–1315 (2008).

- SiegelR, NaishadhamD, JemalA. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J. Clin.63(1), 11–30 (2013).

- ChenFW, SundaramV, ChewTA, LadabaumU. Advanced-stage colorectal cancer in persons younger than 50 years not associated with longer duration of symptoms or time to diagnosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.15(5), 728–737.e723 (2017).

- ChenFW, SundaramV, ChewTA, LadabaumU. Low prevalence of criteria for early screening in young-onset colorectal Cancer. Am. J. Prev. Med.53(6), 933–934 (2017).