Abstract

Aim: To determine the impact of tumor sidedness on all-cause mortality for early- (age 18–49 years) and older-onset (age ≥50 years) colorectal cancer (CRC). Materials & methods: We conducted a retrospective study of 650,382 patients diagnosed with CRC between 2000 and 2016. We examined the associations of age, tumor sidedness (right colon, left colon and rectum) and all-cause mortality. Results: For early-onset CRC (n = 66,186), mortality was highest in the youngest age group (18–29 years), driven by left-sided colon cancers (vs 50–59 years, hazard ratio: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.03–1.34). 5-year risk of death among 18–29-year-olds with left-sided colon cancer (0.42, 95% CI: 0.38, 0.46) was higher than all other age groups. Conclusion: Left-sided colon cancers are enriched in younger adults and may be disproportionately fatal.

Trends in the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer (CRC) have dramatically changed over the past several decades. While incidence and mortality among older adults has declined, the incidence of early-onset CRC (diagnosed before age 50 years) has nearly doubled since the 1990s [Citation1]. Early-onset CRC is now the second most common cancer diagnosis and third leading cause of cancer death in young adults [Citation2]. These tumors appear to have distinct molecular, clinical and epidemiologic features compared with those diagnosed in older adults [Citation3–8].

At the same time, CRC is increasingly recognized as a heterogeneous disease, including differences in epidemiology and biology between so-called ‘right-sided’ versus ‘left-sided’ colon cancers, as well as between colon and rectal cancers, thought to originate from their distinct embryologic origins or changes in the intestinal environmental along the colorectum [Citation9,Citation10]. For example, left-sided or distal colon cancers tend to spread to the lungs and liver, whereas peritoneal carcinomatosis is more common with right-sided or proximal colon cancers [Citation11]. Rectal cancer, given its location within the narrow pelvis, more often recurs locally compared with colon cancers [Citation12]. Others have identified significant differences in molecular profiles by sidedness, notably that right-sided colon cancers have a higher frequency of BRAF mutations, microsatellite instability and CpG island promoter methylation, when compared with left-sided colon cancers [Citation9,Citation13]. Rectal cancers have similar molecular profiles as left-sided colon cancers, although some studies suggest rectal cancers have distinct features, such as KRAS and SMAD4 mutation [Citation14]. Tumor sidedness also predicts response to anti-EGFR therapies, and growing evidence suggests only patients with left-sided colon cancers benefit from cetuximab or panitumumab as first-line therapy for metastatic disease [Citation15,Citation16]. Finally, in terms of survival, right-sided colon cancers are generally associated with worse mortality, although there may be some differences by stage [Citation17–20].

Despite rapid increases in early-onset CRC – and convincing evidence of the predictive and prognostic value of tumor sidedness – there has been limited research on the impact of sidedness in younger adults. Therefore, we used population-based cancer registry data to examine the association between tumor sidedness (left colon, right colon, rectum), age and all-cause mortality, and to determine whether the impact of sidedness on survival differs for early- versus older-onset CRC.

Materials & methods

Study population

We identified persons (age ≥18 years) newly diagnosed with CRC (codes C18.0–C20.9) [Citation21] during 2000–2016 using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of cancer registries. SEER routinely collects data on demographics, primary tumor site, tumor morphology, stage at diagnosis and first course of treatment from all persons diagnosed with cancer in defined geographic regions. The SEER 18 registries cover approximately 28% of the US population and include: Alaska Native Tumor Registry, Connecticut, Detroit, Georgia Center for Cancer Statistics, Greater Bay Area Cancer Registry, Greater California, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Los Angeles, Louisiana, New Mexico, New Jersey, Seattle-Puget Sound and Utah.

Statistical analysis

We compared characteristics of persons diagnosed with early-onset CRC (age 18–49 years) versus older-onset CRC (age ≥50 years) using Chi-square tests. Characteristics included sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, other), year of diagnosis (2000–2003, 2004–2007, 2008–2011, 2012–2016), stage at diagnosis and tumor sidedness. SEER defines stage at diagnosis using historic summary staging: local disease is confined to the large bowel, regional is limited to nearby lymph nodes or other organs and distant is systemic metastasis. We defined tumor sidedness using ICD-O-3 codes: right colon includes the appendix, cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure and transverse colon; left colon includes the splenic flexure, descending colon and sigmoid colon; and rectum includes the rectosigmoid junction and rectum.

We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to examine the associations of age, tumor sidedness and all-cause mortality. Follow-up was accrued from the date of diagnosis until date of death or 31 December 2016. For purposes of analysis, we assigned a follow-up time of 0.5 months to those with 0 months recorded in SEER. We used approximate 10-year age groups (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and ≥70 years) and developed separate models for right colon, left colon and rectum. We built an adjusted model including covariates statistically significantly associated with age and all-cause mortality (p < 0.20): sex, race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis and year of diagnosis. We report crude and adjusted hazards ratios (aHR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

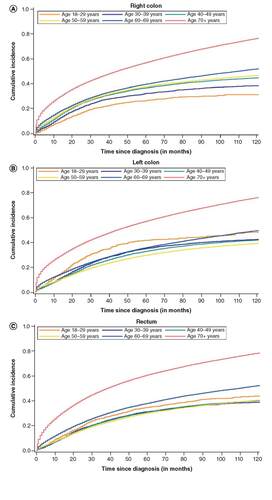

To illustrate findings, we plotted cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality by age, separately for right colon, left colon and rectum. The log-rank test was used to compare all-cause mortality across age groups. We then estimated 5-year risk of all-cause mortality for each age-tumor side group (e.g., age 18–29 years right colon, age 40–49 years left colon).

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, NC, USA).

Results

During the period 2000–2016, 650,382 persons were diagnosed with CRC, representing 66,186 (10.2% of total) and 584,196 (89.8% of total) incident cases of early-onset and older-onset CRC, respectively. A total of 351,677 deaths occurred over approximately 2.9 million person-years of follow-up.

Characteristics of the study population are demonstrated in . A higher proportion of early-onset CRC occurred in men, racial/ethnic minorities and the left colon and rectum (all p < 0.01). Specifically, 30.0% of younger adults were diagnosed with rectal tumors compared with 20.5% of older adults, and there were notable differences in the proportion of tumors in the cecum (8.9 vs 16.2%), ascending colon (7.4 vs 13.7%) and sigmoid colon (21.5 vs 19.3%), by age (p < 0.01). Younger adults more often presented with metastatic disease (26.4 vs 20.6%, p < 0.01).

Table 1. Characteristics of 650,382 people diagnosed with colorectal cancer by age at diagnosis (±50 years), Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results 18, 2000–2016.

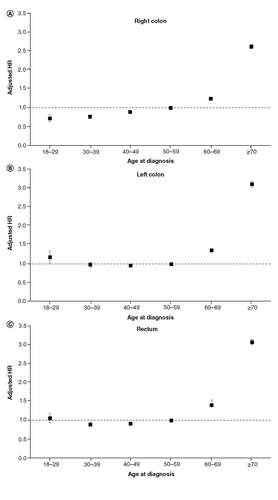

Among those with right-sided colon cancer (n = 262,713), there were marked differences in all-cause mortality by age at diagnosis (). Mortality followed a linear trend (). Compared with age 50–59 years, mortality was lowest at age 18–29 years (aHR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.83, 0.82) and highest at age ≥70 years (aHR: 2.61, 95% CI: 2.56, 2.67). Five-year risk of death similarly ranged from 0.27 (95% CI: 0.24, 0.29) to 0.57 (95% CI: 0.57, 0.58) for the youngest and oldest age groups, respectively ().

Table 2. Crude and adjusted hazard ratios demonstrating association between age at diagnosis and all-cause mortality, by tumor side, Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results 18, 2000–2006.

Adjusted hazard ratios demonstrating association between age at diagnosis and all-cause mortality for right colon (A), left colon (B), and rectal (C) cancer, SEER 18, 2000–2016.

HR: Hazard ratio; SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Result.

Table 3. Five-year risk (95% CI) of all-cause mortality by age at diagnosis and tumor side.

In sharp contrast to right-sided colon cancer, age-related differences in mortality for left-sided colon cancer (n = 169,830) followed a ‘J-shaped’ trend (). Specifically, being diagnosed at age 18–29 years was associated with higher all-cause mortality (aHR: 1.18, 95% CI 1.03, 1.34) when compared with 50–59 year olds (). The 5-year risk of death for 18–29 year olds with left colon cancer (0.42, 95% CI: 0.38, 0.46) was higher than nearly every age group, except those ≥70 years, corresponding to risk differences ranging from 6 to 12% (). Mortality () and 5-year risk of death () for 30–39 and 40–49 year olds was similar to 50–59 year olds.

Cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality by age at diagnosis for right colon (A), left colon (B) and rectal (C) cancer, SEER 18, 2000–2016.

SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Result.

Finally, for those with rectal cancer (n = 187,826), 5-year risk of death was highest for the oldest age groups () but similar (range 0.31–0.34) for all age groups less than 50 years. Compared with 50–59 year olds, mortality was slightly elevated among 18–29 year olds, although this was not statistically significant ().

Discussion

In this population-based study of more than 650,000 adults diagnosed with CRC, all-cause mortality generally increased with age. However, among those diagnosed before age 50 years, mortality was highest in the youngest age group (age 18–29 years), primarily driven by tumors of the left colon. In fact, the 5-year risk of death among 18–29 year olds with left-sided colon cancers exceeded that of nearly all other age groups. Younger adults were also more likely to present with left colon and rectal cancers and to be diagnosed with metastatic disease.

Our study adds to the literature by providing more granular detail on differences in the anatomic distribution of CRC and how these differences disproportionately affect mortality. Prior studies have similarly observed that early-onset CRC occurs more frequently in the left colon and rectum compared with older-onset CRC, where right-sided tumors predominate [Citation3,Citation22–24]. We observed 71% of young adults were diagnosed with left-sided colon or rectal cancers compared with 58% of older adults, and this difference contributed to higher risks of all-cause mortality, even for the youngest age group. Among those diagnosed between ages 18–29 and 30–39, mortality was actually greatest for left-sided colon cancers, even after adjusting for stage at diagnosis. Further, for 18–29 year olds, mortality associated with left-sided colon cancer was higher than 50–59 year old and no better for 30–39 and 40–49 year olds. We were surprised by these findings for several reasons: younger adults are generally healthier and able to receive more aggressive therapies both at initial diagnosis and recurrence; younger patients with tumors in the adjacent right colon fared best and our primary outcome was all-cause mortality, and we expected younger adults to be far less likely to die of competing causes. In contrast, other studies generally report higher mortality among patients diagnosed with right-sided colon cancers [Citation17–20], but these studies comprise predominantly older adults. Our study therefore shows that not only are left-sided colon cancers enriched in younger adults, but they may also be disproportionately fatal. By exploring both the epidemiology and mortality of tumor sidedness in early-onset CRC, our findings have important implications for treatment, screening and etiology.

Given the higher mortality of left-sided colon cancers in younger adults, our results highlight the need for biomarkers that can identify subsets of patients who may benefit from anti-EGFR therapies. Post-hoc analyses of two randomized trials of metastatic CRC demonstrated improved overall survival with the combination of chemotherapy and panitumumab versus chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with RAS wild-type left-sided tumors only [Citation25]. A meta-analysis also demonstrated the predictive value of tumor-sidedness to anti-EGFR therapy in patients diagnosed with RAS wild-type metastatic CRC: those with left-sided colon cancers benefited from anti-EGFR therapy compared with those with right-sided cancers, among whom survival was actually worse when cetuximab or panitumumab was added to their treatment regimen [Citation26]. Given these findings, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has recently included tumor-sidedness in their treatment guidelines, recommending cetuximab or panitumumab only for KRAS wild-type and left-sided metastatic tumors [Citation27]. Treatment recommendations for CRC do not vary by age, although studies have shown that younger patients are more likely to receive aggressive multimodal therapies, with questionable gains [Citation28]. However, because left-sided colon cancers appear disproportionately fatal in young adults, combined with better underlying health status of this age group allowing more intensive therapies, it is possible that a subset of young adults with left-sided cancers may particularly benefit from anti-EGFR therapy.

Higher mortality from left-sided colon and rectal cancers in younger adults also suggests there may be a role for tailored screening approaches in this population, such as flexible sigmoidoscopy. The American Cancer Society recently lowered the recommended age for average-risk screening to 45 (vs 50 recommended by other groups [Citation29]), largely driven by increasing incidence rates of early-onset CRC [Citation30]. Another recent study showing large increases in incidence from age 49 to 50 years further emphasizes the potential benefit of earlier screening [Citation31]. Although colonoscopy is widely considered the ‘gold standard’ in screening, flexible sigmoidoscopy may be an alternative option for younger adults because it visualizes the distal colon and rectum [Citation32,Citation33] without the discomforts of prolonged bowel preparation and sedation. Flexible sigmoidoscopies also have the advantages of convenience and lower cost, and they can be performed by most primary care physicians. Of course, right-sided tumors will be missed by flexible sigmoidoscopy alone and using occult blood testing in combination may increase sensitivity for cancers throughout the entire colorectum. An important next step is to quantify the risk/benefit ratio, cost–effectiveness and patient acceptability of using flexible sigmoidoscopy for screening young adults.

Beyond treatment and screening, age-related differences in tumor sidedness and mortality make a compelling argument for distinct mechanisms driving early- compared with older-onset CRC. Risk factors appear to differ by age [Citation34] and tumor sidedness (). For example, obesity is consistently associated with right-sided colon cancers [Citation35,Citation36] but may have a smaller effect on risk of rectal cancer. Cigarette smoking is also consistently associated with right-sided colon cancer [Citation37–40], likely because smoking is associated with hypermethylation, microsatellite instability and BRAF mutations – common characteristics of these tumors [Citation41]. Risk of rectal cancer is similarly increased in current and former smokers, but it is not yet clear whether this risk is related to a similar mechanism of epigenetic alterations from cigarette smoking observed in right-sided colon cancer. Finally, ‘Western’ diets high in red or processed meats, added sugars and refined grains are associated with higher risk of left-sided compared with right-sided colon cancers [Citation42]. Our findings underscore the importance of better understanding the etiology of sidedness and how these etiologic differences may also contribute to differences in survival.

Table 4. Summary of risk factors for right colon, left colon and rectal cancer.

Limitations of our study include lack of information in SEER data on tumor-specific genetic factors, such as KRAS or BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability and comorbidities predisposing higher risk, such as inflammatory bowel disease or familial syndromes. Further, the SEER program does not routinely collect type of chemotherapy, radiation dose or toxicities of treatment. However, these limitations would not affect interpretation of our findings related to tumor sidedness, and the majority of published statistics on cancer survival are treatment agnostic. There was some missing data on patient and tumor characteristics, including tumor location, however the proportion with missing data was low (<5%). Finally, because guidelines recommend similar treatment for rectosigmoid and rectal cancers, we grouped these together as rectal cancers. It is possible that some rectosigmoid cancers were mostly located in the distal colon, with only a small portion traversing the rectum. However, we would expect any misclassification to bias our findings toward the null because we observed worse mortality among young adults with left colon, compared with rectal cancers.

Conclusion & future perspective

In summary, our study suggests that among those with early-onset CRC, mortality is highest in the youngest age group (less than 30 years), driven by left-sided colon cancers. The ‘J-Shaped’ trend in mortality for left colon cancer also shows the disproportionate impact of this disease by age. We suspect that as-yet-unknown environmental and genetic factors driving excess incidence of left-sided colon cancers in young adults similarly contribute to more aggressive tumor biology, perhaps leading to treatment resistance and higher all-cause mortality. Future studies are needed to elucidate the molecular underpinnings of this disparity, including research on risk factors and differences in the microbiome and molecular profile by tumor sidedness. If our findings are supported by additional studies, they could have important implications for the management of CRC, such as integrating age and tumor sidedness into screening and treatment recommendations. In the meantime, ongoing trials should consider stratifying their outcomes by side-associated and age variables, which will allow for more rapid tailoring of future care for early-onset CRC.

Among 650,382 patients newly diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) between 2000 and 2016, about 10% (n = 66,186) were aged 18–49 and classified as early-onset CRC.

Patients with early onset-CRC were more likely to have tumors located in the left colon and rectum and to present with metastatic disease compared with patients with older-onset CRC diagnosed at age 50 years or more.

Among those with early-onset CRC, all-cause mortality was highest for the youngest age group (18–29 years) and similar for the 30–39 and 40–49-year age groups.

In patients with right colon cancers, all-cause mortality increased successively by age and was highest for age ≥70 years.

All-cause mortality for rectal cancers also generally increased by age, although it was similar for all ages 18–69 years and increased at age ≥70 years.

In contrast, for left colon tumors, all-cause mortality followed a ‘J-shaped’ trend, whereby mortality was highest for the youngest (age 18–29 years) and oldest (age ≥70 years) groups.

Among patients age 18–29 years, 5-year risk of death was highest for those with left colon cancer. Notably, this is in contrast to previous studies, comprising predominantly older adults, suggesting right colon cancers have a worse prognosis.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health under award number R01CA242558 (CC Murphy) and the Dedman Family Scholars in Clinical Care at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (NN Sanford). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- SiegelRL, FedewaSA, AndersonWFet al.Colorectal Cancer Incidence Patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J. Natl Cancer Inst.109(8), djw322 (2017).

- HofsethLJ, HebertJR, ChandaAet al.Early-onset colorectal cancer: initial clues and current views. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.doi:10.1038/s41575-019-0253-4 (2020) ( Epub ahead of print).

- ChangDT, PaiRK, RybickiLAet al.Clinicopathologic and molecular features of sporadic early-onset colorectal adenocarcinoma: an adenocarcinoma with frequent signet ring cell differentiation, rectal and sigmoid involvement, and adverse morphologic features. Mod. Pathol.25(8), 1128–1139 (2012).

- LimburgPJ, HarmsenWS, ChenHHet al.Prevalence of alterations in DNA mismatch repair genes in patients with young-onset colorectal cancer. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.9(6), 497–502 (2011).

- WillauerAN, LiuY, PereiraAaLet al.Clinical and molecular characterization of early-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer125(12), 2002–2010 (2019).

- JacobsD, ZhuR, LuoJet al.Defining early-onset colon and rectal cancers. Front. Oncol.8, 504 (2018).

- AhnenDJ, WadeSW, JonesWFet al.The increasing incidence of young-onset colorectal cancer: a call to action. Mayo Clin. Proc.89(2), 216–224 (2014).

- KetsCM, Van KriekenJH, Van ErpPEet al.Is early-onset microsatellite and chromosomally stable colorectal cancer a hallmark of a genetic susceptibility syndrome?Int. J. Cancer122(4), 796–801 (2008).

- LeeMS, MenterDG, KopetzS. Right versus left colon cancer biology: integrating the consensus molecular subtypes. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw.15(3), 411–419 (2017).

- WangC, WainbergZA, RaldowA, LeeP. Differences in cancer-specific mortality of right- versus left-sided colon adenocarcinoma: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database analysis. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform.1, 1–9 (2017).

- RiihimakiM, HemminkiA, SundquistJ, HemminkiK. Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Sci. Rep.6, 29765 (2016).

- KustersM, MarijnenCA, VanDe Velde CJet al.Patterns of local recurrence in rectal cancer; a study of the Dutch TME trial. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol.36(5), 470–476 (2010).

- IacopettaB. Are there two sides to colorectal cancer?Int. J. Cancer101(5), 403–408 (2002).

- ZhangZ, WangA, TangX, ChenY, TangE, JiangH. Comparative mutational analysis of distal colon cancer with rectal cancer. Oncol. Lett.19(3), 1781–1788 (2020).

- DouillardJY, OlinerKS, SienaSet al.Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med.369(11), 1023–1034 (2013).

- Van CutsemE, LenzHJ, KohneCHet al.Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.33(7), 692–700 (2015).

- PetrelliF, TomaselloG, BorgonovoKet al.Prognostic survival associated with left-sided vs right-sided colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol.3(2), 211–219 (2017).

- BenedixF, KubeR, MeyerFet al.Comparison of 17,641 patients with right- and left-sided colon cancer: differences in epidemiology, perioperative course, histology, and survival. Dis. Colon Rectum53(1), 57–64 (2010).

- MeguidRA, SlidellMB, WolfgangCL, ChangDC, AhujaN. Is there a difference in survival between right- versus left-sided colon cancers?Ann. Surg. Oncol.15(9), 2388–2394 (2008).

- WeissJM, PfauPR, O’connorESet al.Mortality by stage for right- versus left-sided colon cancer: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results–Medicare data. J. Clin. Oncol.29(33), 4401–4409 (2011).

- World Health OrganisationInternational Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O)(3rd Edition). PercyC, JackA, ParkinMD ( Eds). World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland (2000).

- DozoisEJ, BoardmanLA, SuwanthanmaWet al.Young-onset colorectal cancer in patients with no known genetic predisposition: can we increase early recognition and improve outcome?Medicine87(5), 259–263 (2008).

- SegevL, KaladyMF, ChurchJM. Left-sided dominance of early-onset colorectal cancers: a rationale for screening flexible sigmoidoscopy in the young. Dis. Colon Rectum61(8), 897–902 (2018).

- SnaebjornssonP, JonassonL, JonssonT, MollerPH, TheodorsA, JonassonJG. Colon cancer in Iceland–a nationwide comparative study on various pathology parameters with respect to right and left tumor location and patients age. Int. J. Cancer127(11), 2645–2653 (2010).

- BoeckxN, KoukakisR, OpDe Beeck Ket al.Primary tumor sidedness has an impact on prognosis and treatment outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from two randomized first-line panitumumab studies. Ann. Oncol.28(8), 1862–1868 (2017).

- ArnoldD, LuezaB, DouillardJYet al.Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann. Oncol.28(8), 1713–1729 (2017).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Colon Cancer (Version 2.2020). www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf

- KneuertzPJ, ChangGJ, HuCYet al.Overtreatment of young adults with colon cancer: more intense treatments with unmatched survival gains. JAMA Surg.150(5), 402–409 (2015).

- Final Recommendation Statement: Colorectal Cancer: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2020). www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/RecommendationStatementFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening1

- WolfAMD, FonthamETH, ChurchTRet al.Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J. Clin.68(4), 250–281 (2018).

- AbualkhairWH, ZhouM, AhnenD, YuQ, WuXC, KarlitzJJ. Trends in incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer in the united states among those approaching screening age. JAMA Netw. Open3(1), e1920407 (2020).

- HolmeO, LobergM, KalagerMet al.Effect of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA312(6), 606–615 (2014).

- SchoenRE, PinskyPF, WeissfeldJLet al.Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. N. Engl. J. Med.366(25), 2345–2357 (2012).

- CavestroGM, MannucciA, ZuppardoRA, DiLeo M, StoffelE, TononG. Early onset sporadic colorectal cancer: worrisome trends and oncogenic features. Dig Liver Dis50(6), 521–532 (2018).

- JohnsonCM, WeiC, EnsorJEet al.Meta-analyses of colorectal cancer risk factors. Cancer Causes Control24(6), 1207–1222 (2013).

- World Cancer Research Fund. Aicr, Wcrf. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and colorectal cancer. (2017). www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Colorectal-cancer-report.pdf

- WeiEK, ColditzGA, GiovannucciELet al.A comprehensive model of colorectal cancer by risk factor status and subsite using data from the nurses’ health study. Am. J. Epidemiol.185(3), 224–237 (2017).

- DembJ, EarlesA, MartínezMEet al.Risk factors for colorectal cancer significantly vary by anatomic site. BMJ Open Gastroenterol.6(1), e000313 (2019).

- MurphyN, WardHA, JenabMet al.Heterogeneity of colorectal cancer risk factors by anatomical subsite in 10 European countries: a multinational cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol. Hepatol.17(7), 1323–1331.e1326 (2019).

- LeufkensAM, Van DuijnhovenFJ, SiersemaPDet al.Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.9(2), 137–144 (2011).

- LimsuiD, VierkantRA, TillmansLSet al.Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer risk by molecularly defined subtypes. J. Natl Cancer Inst.102(14), 1012–1022 (2010).

- MehtaRS, SongM, NishiharaRet al.Dietary patterns and risk of colorectal cancer: analysis by tumor location and molecular subtypes. Gastroenterol.152(8), 1944–1953.e1941 (2017).

- RobsahmTE, AagnesB, HjartakerA, LangsethH, BrayFI, LarsenIK. Body mass index, physical activity, and colorectal cancer by anatomical subsites: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur. J. Cancer Prev.22(6), 492–505 (2013).

- DongY, ZhouJ, ZhuYet al.Abdominal obesity and colorectal cancer risk: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Biosci. Rep.37(6), BSR20170945 (2017).

- HidayatK, YangCM, ShiBM. Body fatness at an early age and risk of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer142(4), 729–740 (2018).

- FedirkoV, TramacereI, BagnardiVet al.Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies. Ann. Oncol.22(9), 1958–1972 (2011).