Abstract

Background: The avoidance of prolonged hospital stay is a major goal in the management of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) – medically and economically. Materials & methods: We compared the time range of the preprocedural length of stay in 2014/2015 with 2016/2017, after the implementation of the TAVI coordinator in 2016. This included restructured pathways for screening and pre-interventional diagnosis, performed examinations during the inpatient stay and major outcome variables. Results: After 2016, we observed a significant reduction in preprocedural length of stay (admission to procedure) compared with 2014/2015 (11.3 ± 7.9 vs 7.5 ± 5.6 days, p = 0.001). There was no difference in other major outcome variables. Conclusion: The introduction of the TAVI coordinator caused a shortening of preprocedural length of stay.

Over one million people in Europe aged 75 years and older exhibit a severe aortic stenosis, and due to the demographic change, the incidence is still rising [Citation1]. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is recommended in patients who are not eligible for surgical aortic valve replacement due to older age and/or increased surgical risk [Citation2]. Given concerns regarding eligible TAVI patients who are more often elderly with increased comorbidities, it is necessary to identify determinants to improve outcomes. A potential surrogate for improved quality of care is the length of stay. Prolonged inpatient stays have already been shown to be associated with a higher risk of nosocomial infections, including pneumonia and urinary tract infections [Citation3–5] and subsequent utilization of healthcare resources, as well as associated cost of care for the healthcare provider [Citation6–8]. While some factors, such as patient age and severity of disease, were observed as independent predictors of prolonged hospital stays in patients undergoing TAVI [Citation9], no model for the optimization of the inner clinical processing in TAVI exists so far. In contrast to most cardiologic diseases, TAVI is a mostly electively planned procedure and therefore offers the opportunity for planned processing.

The present study aimed to analyze the impact of clinical process optimization on the length of stays in 2014/2015 compared with 2016/2017 after the introduction of a TAVI coordinator in 2016.

Materials & methods

Study design & population

All patients undergoing transfemoral TAVI at the West German Heart and Vascular Center between 2014 and 2017 were included in the retrospective analysis. The indication followed the current guidelines respecting special patient characteristics at the discretion of the treating physician. All patients were discussed in the weekly Heart Team conference as required by the European guidelines for valvular heart diseases [Citation10]. No exclusion criteria were applied. Basic demographic data, including EuroScore, comorbidities, preparatory TAVI-examinations (at our department and at outside facilities) and 30-day mortality were assessed. The preprocedural length of stay (day of admission to day of procedure) and postprocedural length of stay (day of procedure to day of dismissal) were assessed. Since the introduction of the TAVI coordinator took place in the beginning of 2016, we analyzed the time periods 2014/2015 and 2016/2017.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of our institution and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient records were de-identified and analyzed anonymously. The local ethics committee approved the retrospective analysis of patient data without the need to obtain patient consent.

Implementation of the TAVI coordinator

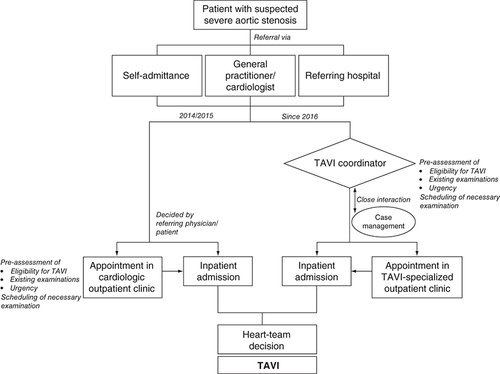

Since 2016, we implemented a TAVI coordinator as the first contact person for patients with planned TAVI procedure or already implanted TAVI (). The TAVI coordinator is a TAVI-experienced (senior) consultant, who is involved in and performs all TAVI procedures. The TAVI coordinator is also involved in the coordination of appointments for screening and implantation by the case management, is part of the local Heart Team and operates the specialized outpatient clinic for TAVI. The TAVI coordinator is reachable for treating general practitioners/cardiologists or outside facilities through the ‘aortic valve-hotline’ aiming for an easy scheduling of appointments.

The TAVI coordinator serves as interface between coordination and optimization of external relations to general practitioners and cardiologists and the optimization of the intrahospital flow. The TAVI coordinator is only involved in the context of TAVI-related examinations and procedures and supports the nonmedical staff with administrative activities.

The TAVI coordinator was introduced to address the need for an internal pre-assessment of potentially eligible TAVI candidates before an outpatient appointment or admission by screening medical records and/or telephone consultation with the treating primary physician or cardiologist. The purpose was to avoid the unnecessary repetition of examinations already carried out in outside facilities, to identify the necessary repetition of examinations due to, for example, impaired imaging quality and to schedule necessary examinations in advance to access a reliable schedule for each patient. It should be noted that the internal pre-assessment of the TAVI coordinator is not binding for a further Heart Team decision. The need for a Heart Team consensus is mandatory following the decree of the Federal Joint Committee since 2015.

The implementation of the TAVI coordinator was part of a restructuring initiative and included also the implementation of a specialized outpatient clinic for patients with aortic valve stenosis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as means ± standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Chi-square test was used for comparing categorical variables. Student’s t-test was used for the analysis of continuous variables. We used the Mann–Witney U test for the comparison of time ranges. Data referred to time ranges were presented as median and interquartile ranges. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data and statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24 (IL, USA) for Mac and Microsoft Excel 2011 for Mac.

Results

TAVI procedures & basic patient demographics

In the observational period between 2014 and 2017, 458 patients underwent transfemoral TAVI. An almost continuous increase in transfemoral TAVI procedures was seen annually; while 71 patients received implants in 2014, an increase of 85% up to 131 procedures in 2015 was detected. In 2016, there was a slight decrease of 19% in implanted TAVI to 109 procedures. The following year, 2017, showed an increase up to 147 procedures.

Basic patient demographics for both periods are shown in . Periprocedural risk, as assessed by EuroScore I, ejection fraction and relevant comorbidities were comparable between both periods. The higher age in 2016/2017 made the only exception between both groups.

Table 1. Patient demographics.

Preparatory examinations before inpatient stay

Preparatory examinations for TAVI included transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiography for valve assessment, coronary angiography to capture the status of a potential coronary disease and a computed tomography (CT) angiography from the aortic valve level down to the femoral artery by using the femoral approach.

The total number of performed coronary angiograms was high in both groups (n = 201 vs 255, p = 0.482) in order to assess the actual coronary status. Almost half of the performed coronary angiograms in both groups were performed in-hospital (n = 97 vs 133, p = 0.472). The number of needed percutaneous coronary interventions was also comparable in both groups (n = 36 vs 35, p = 0.206). All patients received a computed tomography before valve implantation. The number of CT angiographies carried out in outside facilities or within previous inpatient stays was comparatively small (n = 39 vs 66, p = 0.105). The same tendency was seen in terms of transesophageal echocardiography. All patients had transesophageal echocardiography in advance and only a minority (n = 12 vs 10, p = 0.310) had this examination carried out in outside facilities or within previous inpatient stays.

The main relevant factors for the prolongation of the preprocedural length of stay were associated with necessary preliminary examinations and were comparable in both groups for coronary angiography (n = 97 vs 133, p = 0.472), CT (n = 39 vs 65, p = 0.105) and transesophageal echocardiography (n = 12 vs 10, p = 0.310; ).

Table 2. Comparison of main relevant examinations covering pretranscatheter aortic valve implantation inpatient stay between 2014/2015 and 2016/2017.

It is remarkable, that the number of repeated examinations during the inpatient stay decreased significantly from 2014/2015 to 2016/2017 for coronary angiography (n = 63 vs 34, p = 0.001) and CT (n = 30 vs 21, p = 0.022). Only the number for transesophageal echocardiography remained largely stable (n = 10 vs 5, p = 0.126; ).

Comparison of length of stays & major outcome variables

The total length of stay decreased from 2014/2015 to 2016/2017 with a median of 21 days [Citation11] to 14 days [Citation12] (p = 0.001). Comparing the needed time for preparatory examination until TAVI procedure, we found a significant shorter duration from the day of admission to implantation in 2016/2017 (2014/2015: 9 days [Citation7,Citation13], 2016/2017: 6 days [Citation3,Citation10]; p = 0.001). The same tendency was seen for the time range from implantation to discharge (2014/2015: 9 days [Citation7,Citation11], 2016/2017: 7 days [Citation6,Citation12]; p = 0.001).

Although we observed a reduction of days of inpatient stay, major outcome variables did not differ: 30-day mortality showed a slight decreasing tendency without a significant difference. The number of postprocedural pacemaker implantation and femoral access complications were also comparable between both groups ().

Table 3. Comparison of length of stays and patients’outcomes between 2014/2015 and 2016/2017.

Discussion

The current study investigated the influence of clinical restructuration on the reduction of the preprocedural length of stay in patients undergoing TAVI. The shortening of inpatient stays has already been shown to be beneficial for major outcome variables, is a surrogate factor for quality of care, and comes with high cost reduction potential.

For this purpose, all transfemoral TAVI procedures performed at the West German Heart and Vascular Center between 2014 and 2017 were evaluated. In particular, the days of preprocedural inpatient stay in 2014/2015 compared with 2016/2017 were analyzed, following the implementation of the TAVI coordinator in 2016. The effects of prolonged inpatient stays, especially for older patients, have been shown to be linked to a worse outcome [Citation12,Citation14]. Additionally, the pressure of rising costs in the healthcare sector demands the reduction of the length of stay, and therefore, such reduction is gaining increasing importance as a measure to counteract this trend. In comparison to surgical aortic replacement, TAVI has still higher procedural costs, but there is a chance of compensation mainly through shortened inpatient stays and reduced need for rehabilitation [Citation13,Citation15]. Shortening of the length of stay in patients undergoing TAVI has previously been shown to not be associated with an early readmission or higher 30-day mortality [Citation11,Citation16].

Based on the present results, we were able to show that the implementation of a TAVI coordinator who has supervisory responsibility and duties in TAVI organization led to a reduction in the length of preprocedural inpatient stay, in particular. We could demonstrate a correlation between an improved workflow and a smoother operation by concentrating organizational power in the TAVI coordinator. One main relevant factor for the implementation of the TAVI coordinator was the moving forward of pre-assessment from an experienced TAVI specialist to optimize the prescheduling of necessary examinations before implantation and to avoid redundant and expensive imaging without additional relevance. We saw a significant decrease of redundant preparatory examinations for coronary angiographies and CTs. No differences in repeated transesophageal echocardiographies could be shown. That might be because of the missing standardized protocol for transesophageal echocardiography and the lacking possibility of reconstructional imaging data.

We also attached a specialized outpatient clinic for patients with severe aortic valve stenosis, which was also introduced at the beginning of 2016. Its aim was to define a therapy pathway suitable for the patient before the actual inpatient stay, and it represents the basis for further interventional, surgical or conservative treatment. The goal is to plan the further therapeutic procedure together with the patient through a TAVI-experienced specialist and, if necessary, to schedule inpatient admission including the necessary preliminary examinations. By the initiation of a special outpatient clinic on pre- and post-interventional care, we adhere to the structural, professional and personal requirements in order to perform the TAVI procedure. The reorganization of the outpatient clinic targeted the length of inpatient stay, in particular the preprocedural length of stay, that was often subsidized by healthcare providers until 2015 when the upper length of stay was exceeded [Citation6,Citation7,Citation17]. The decrease in the preprocedural inpatient length of stay might reduce the risk of exceeding the upper length of stay, but due to the increasing complexity of procedures in a group of patients that is by definition older and severely ill with a high risk of complications such as postinterventional bleeding, prolonged intensive care unit stay cannot be completely avoided [Citation18]. In these cases especially, a detailed and complete documentation with regard to medical justification is required [Citation19].

Limitations

The current study discusses the length of inpatient stays but does not state outcome variables beyond the 30-day mortality. Additionally, no calculation of definite cost savings was performed, because statements about definite cost savings are difficult to provide as the healthcare system differs between countries. However, reducing the length of stay indicates savings in this sector. The analysis of economic questions often excludes patient-centered interrogations. Hence, patient satisfaction with the shortening of preprocedural length of stay was not assessed. Additionally, no data on nosocomial infections were included, leading to an impaired assessment of the clinical relevance.

As severe aortic stenosis is mainly characterized by slow progression, most planned TAVI procedures are planned electively. The transfer to other diseases might be restricted. The present study refers to the German health system, including accounting for national characteristics. A special feature of the German healthcare system is the financial penalty for falling below the lower length of stay, avoiding a further reduction of in-hospital stay. The transfer into a different health system is limited, but economization is a global goal. The preprocedural streamlining of preliminary examinations might be among the first steps toward accounting for this issue.

Conclusion

The early pre-assessment of potential TAVI candidates aims for inner-clinical optimization by avoidance of unnecessary repetition of examinations, identification of necessary repetition of examinations, and scheduling of necessary examinations in advance to access a reliable schedule for each patient and reduce the risk of adverse outcomes associated with a prolonged length of stay. Through the introduction of the TAVI coordinator, we particularly found a significant reduction of preprocedural length of stay, without an increase in postprocedural major outcome variables.

The introduction of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) enabled the therapeutic option for patients with severe aortic stenosis who were ineligible for surgical aortic valve replacement.

The reduction in hospital length of stay is a major medically and economically goal. Through the appointment of a centralized TAVI coordinator in 2016 at our department, we aimed for an earlier pre-assessment of patients and necessary examinations to reduce the preprocedural length of stay.

In total, we analyzed 458 patients, who underwent TAVI between 2014 and 2017.

After the implementation of the TAVI coordinator in 2016, we observed a significant reduction in preprocedural length of stay (admission to procedure) compared with 2014/2015.

No difference in 30-day mortality, the postprocedural pacemaker implantation or major femoral complication was observed.

In summary, the introduction of the TAVI coordinator caused a shortening of preprocedural length of stay.

This had no influence on major outcome variables like 30-day mortality, postprocedural pacemaker implantation or femoral complication.

Author contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work was given by J Lortz, TP Lortz, L Johannsen, RA Jánosi and T Rassaf. Data acquisition was done by L Johannsen, C Rammos and A Lind. Data analysis was performed by J Lortz, M Steinmetz, TP Lortz and RA Jánosi. Interpretation of data for the work was done by J Lortz, TP Lortz, T Rassaf and RA Jánosi. Drafting the work was done by J Lortz, TP Lortz, C Rammos, M Steinmetz A Lind, T Rassaf and RA Jánosi and revising it critically for important intellectual content was done by L Johannsen, M Steinmetz, T Rassaf and RA Jánosi. All authors did the final approval of the version to be published. All authors did the agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethical conduct of research

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Duisburg-Essen and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient records were de-identified and analyzed anonymously. The local ethics committee approved the retrospective analysis of patient data without the need to obtain patient consent.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The authors certify that this manuscript reports original clinical trial data. Individual, de-identified participant data that underlie the results reported in this article (text, tables, figures, and appendices) will be available to anyone who wishes to access the data, for any purpose. Data will be available immediately following publication with no end date. Proposals should be directed to the corresponding author (A Janosi, [email protected]). To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

References

- Iung B , BaronG, ButchartEGet al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: the euro heart survey on valvular heart disease. Eur. Heart J., 24(13), 1231–1243 (2003).

- Baumgartner H , FalkV, BaxJJet al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur. Heart J., 38(36), 2739–2791 (2017).

- Kaye KS , MarchaimD, ChenTYet al. Effect of nosocomial bloodstream infections on mortality, length of stay, and hospital costs in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc., 62(2), 306–311 (2014).

- Mitchell BG , FergusonJK, AndersonM, SearJ, BarnettA. Length of stay and mortality associated with healthcare-associated urinary tract infections: a multi-state model. J. Hosp. Infect., 93(1), 92–99 (2016).

- Menendez R , FerrandoD, VallesJM, MartinezE, PerpinaM. Initial risk class and length of hospital stay in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J., 18(1), 151–156 (2001).

- Accordino MK , WrightJD, VasanS, NeugutAI, HillyerGC, HershmanDL. Factors and costs associated with delay in treatment initiation and prolonged length of stay with inpatient EPOCH chemotherapy in patients with hematologic malignancies. Cancer Invest., 35(3), 202–214 (2017).

- Reed T Jr , VeithFJ, GargiuloNJ3rdet al. System to decrease length of stay for vascular surgery. J. Vasc. Surg., 39(2), 395–399 (2004).

- Abdelnoor M , AndersenJG, ArnesenH, JohansenO. Early discharge compared with ordinary discharge after percutaneous coronary intervention - a systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and cost. Vasc. Health Risk Manag., 13, 101–109 (2017).

- Arbel Y , ZivkovicN, MehtaDet al. Factors associated with length of stay following trans-catheter aortic valve replacement - a multicenter study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord., 17(1), 137 (2017).

- Vahanian A , AlfieriO, AndreottiFet al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012): the Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg., 42(4), S1–S44 (2012).

- Sud M , QuiF, AustinPCet al. Short length of stay after elective transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement is not associated with increased early or late readmission risk. J. Am. Heart Assoc., 6(4), (2017).

- Chevreul K , BrunnM, CadierBet al. Cost of transcatheter aortic valve implantation and factors associated with higher hospital stay cost in patients of the FRANCE (FRench Aortic National CoreValve and Edwards) registry. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis., 106(4), 209–219 (2013).

- Reynolds MR , MagnusonEA, WangKet al. Cost-effectiveness of transcatheter aortic valve replacement compared with standard care among inoperable patients with severe aortic stenosis: results from the placement of aortic transcatheter valves (PARTNER) trial (Cohort B). Circulation, 125(9), 1102–1109 (2012).

- George AJ , BoehmeAK, SieglerJEet al. Hospital-acquired infection underlies poor functional outcome in patients with prolonged length of stay. ISRN Stroke, 2013, (2013). doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/312348

- Reynolds MR , LeiY, WangKet al. Cost–effectiveness of transcatheter aortic valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis versus surgical aortic valve replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., 67(1), 29–38 (2016).

- Kotronias RA , TeitelbaumM, WebbJGet al. Early versus standard discharge after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC. Cardiovasc. Interv., 11(17), 1759–1771 (2018).

- Skillman JJ , ParasC, RosenM, DavisRB, KimD, KentKC. Improving cost efficiency on a vascular surgery service. Am. J. Surg., 179(3), 197–200 (2000).

- Cremer J , HeinemannMK, MohrFWet al. [Commentary by the German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery on the positions statement by the German Cardiology Society on quality criteria for transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)]. Thoracic Cardiovasc. Surg., 62(8), 639–644 (2014).

- Braun JP , BauseH, BloosFet al. Peer reviewing critical care: a pragmatic approach to quality management. Ger. Med. Sci., 8, Doc23 (2010).