Abstract

The management of patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome, especially in prehospital settings, is challenging. This Special Report focuses on studies in emergency medical services concerning chest pain patients’ triage and risk stratification. In addition, it emphasizes advancements in point-of-care cardiac troponin testing. These developments are compared with in-hospital guidelines, proposing an initial framework for a new acute care pathway. This pathway integrates a risk stratification tool with high-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing, aiming to deliver optimal care and collaboration within the acute care chain. It has the potential to contribute to a significant reduction in hospital referrals, reduce observation time and overcrowding at emergency departments and hospital admissions.

Chest pain evaluation remains a worldwide challenge creating diagnostic uncertainties both at emergency medical services (EMS) and at the emergency department (ED). It is one of the most common complaints for urgent ambulances rides and the large volume of chest pain patients at the ED causes overcrowding.

Since the late 1990s, much has changed in the triage and treatment of patients with chest pain in the acute care chain, especially in the ambulance. The introduction of portable 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) devices, combined with highly educated ambulance personnel, facilitated the diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI) much earlier in the care process than before. This prehospital ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) diagnosis resulted in direct referral to a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) center thereby improving time-to-treatment. Besides that, early STEMI diagnosis also led to prehospital initiation of antithrombotic and antiplatelet agents which also improved patient outcome [Citation1,Citation2].

However, of all patients presenting with chest pain to the EMS, only a small percentage (~5%) have an evident STEMI, while only 20% of patients presenting to the ED are diagnosed with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The remaining 80% usually spend several hours at the ED in diagnostic uncertainty while the majority of them end up with a non-cardiac diagnosis at discharge [Citation3].

In the prehospital setting, for EMS personnel and general practitioners in particular, it can be challenging to early identify patients at (very) low risk for an ACS with limited diagnostic options. However, if general practitioners and EMS personnel would play a more prominent role in the early triage of patients with chest pain or suggestive symptoms, this could significantly reduce hospital referral, ED overcrowding, overdiagnosis and hospital admissions. In order to increase diagnostic certainty, they should be supported by a risk stratification tool combined with a (high-sensitivity) point-of-care (POC) cardiac troponin measurement. In recent years, the sensitivity of these POC measurements has continued to improve, increasing their reliability and usefulness for early and rapid rule out of ACS, without the use of a central laboratory. Ideally, in addition to this prehospital diagnostic strategy, (high-sensitivity) POC troponin could also be implemented at the ED, decreasing time to diagnosis and decreasing overcrowding at the ED.

This Special Report aims to provide information on recently acquired and published evidence in prehospital studies on risk stratification in patients suspected for non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS). Besides this overview, it also has the objective of providing suggestions for application in daily practice and giving direction for better harmonization in the acute cardiac care chain.

Current ACS management prehospital versus in-hospital

Inside the hospital, chest pain management worldwide is well defined in guidelines such as from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American Heart Association (AHA), suggesting on a combination of clinical presentation and symptoms, vital parameters, ECG and cardiac troponin levels to support clinical decision making [Citation4,Citation5].

These guidelines mainly describe in-hospital triage and diagnosing in patients suspected for NSTE-ACS. The description of the prehospital situation is lacking in these guidelines, particularly when it comes to rule out an acute coronary syndrome. Prehospital rule in has scope in the guidelines. Mainly focused on medication and direct referral to, for example, an interventional center for a primary PCI. But current guidelines do not address the prehospital management for the group at (very) low risk of acute coronary syndrome, who may not need to be referred to an ED at all.

In the past decade, several studies have focused on improved triage and care of patients with chest pain in the prehospital setting, including the use of risk stratification and POC troponin [Citation6–18]. However, so far, these studies have not led to a widespread implementation of this approach and a change in common practice.

When evaluating a patient with chest pain, general practitioners often lack the option to perform and read an ECG or to measure a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn). Therefore, triage in the prehospital setting is often dependent on EMS support [Citation19] and thus this review is focused mainly on research performed in that setting.

Currently, most EMS guidelines and protocols do not focus on the decision-making process of the ambulance personnel and their autonomous decisions, but emphasize on a low threshold for hospital referral. Depending on education of EMS professionals and their permission to make independent decisions, local protocols might vary widely.

Cardiac troponin

Cardiac troponin is the most sensitive and specific biomarker of cardiomyocyte injury. Levels of cardiac troponin rise rapidly after symptom onset. Developments in technology, including the availability of hs-cTn, have improved the diagnostic accuracy for MI. A combination of a suspicious history and a (dynamic) troponin elevation above the 99th percentile indicates an MI. The improvements in troponin diagnostics have not only been limited to central laboratory devices. A recent study demonstrated comparable diagnostic accuracy between a POC assay and an assay in a central laboratory using 99th percentiles [Citation20]. Several other studies demonstrated also an increase in sensitivity and negative predictive values for POC hs-cTn measurements. From here, suggestions are made, even with a single determination of hs-cTn, to rapidly identify patients to be at low or high risk for an ACS which can either lead to rapid discharge from the ED or faster rerouting for advanced care at an intervention center [Citation20–26].

The currently available high-sensitivity POC troponin devices, with or without a risk stratification tool, all support in identifying both low- and high-risk patients, which improves early rule in and rule out of an ACS and improves therapeutic and referral decisions. It is important in the prehospital setting to use a robust handheld device with a short measurement time and the highest possible sensitivity. lists currently available devices that meet these specifications to a greater or lesser extent.

Table 1. Handheld point of care cardiac troponin devices and specifications.

Risk stratification & prehospital studies

In terms of risk stratification, within hospitals, in patients with chest pain, currently the widely validated HEART score (History, ECG, Age, Risk factors and Troponin) is the most commonly used (). The HEART score adequately stratifies patients into low, intermediate and high risk for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) [Citation27,Citation28]. In a study comparing different risk stratification tools, the HEART score outperformed the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) and Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score [Citation29]. This same study by Poldervaart et al. describes that the HEART score is specifically developed to be used in unselected patients with chest pain. The TIMI and GRACE score are more suitable as a further prognostic score in patients already diagnosed with an ACS. Other described and validated risk stratification tools are the Emergency Department Assessment of Chest Pain (EDACS) score and the Troponin-only Manchester Acute Coronary Syndromes (T-MACS) decision aid. Given the in-hospital performance of the EDACS, TIMI and T-MACS scores it is imaginable that these risk scores would have similar performance when implemented in the prehospital setting. However, these instruments have not (yet) been researched and published from this prehospital perspective.

Table 2. Calculation of the history, electrocardiogram, age, risk factors and troponin score.

In order to improve prehospital triage, several studies are performed, assessing the safety and efficacy of prehospital triage by EMS personnel. The FamouS Triage study demonstrated the feasibility of prehospital triage of chest pain patients by EMS personnel, based on the HEART score, using contemporary POC troponin T (Roche Cobas h232) [Citation7,Citation8,Citation17]. The study showed that not transferring low-risk patients to a hospital, is feasible and noninferior to transferring all patients to the hospital [Citation11].

A similar study, the ARTICA trial, investigated the safety and efficacy of a prehospital rule out strategy with the HEART score [Citation15,Citation30]. Randomizing patients with a low HEAR score ≤3 (without T) to either evaluation in the ED (current practice) or prehospital rule out based on a contemporary POC troponin T measurement (Roche Cobas h232) and thus completing a prehospital HEART score. This study focused on the reduction of healthcare costs, patient anxiety and ED overcrowding. Mean healthcare costs were significantly lower in the prehospital rule out strategy. MACE rate in both groups was comparable and in patients where ACS was ruled out by POC troponin a very low MACE rate was observed, comparable to patients with ACS ruled out at the ED (0.5% vs 1.0%, P-0.41) [Citation13].

In the pre-HEART study [Citation16], triage decisions of EMS personnel were based on a modified version of the HEART score plus a contemporary POC troponin I (Abbott i-STAT). The authors concluded that the pre-HEART score is reliable and useful in prehospital decision making [Citation31].

The PORT trial [Citation10] investigated the agreement between the HEART score using a contemporary POC troponin T (Roche Cobas h232) and the HEART score using a central laboratory high-sensitivity assay. It showed an almost perfect agreement which supports the implementation of the HEART score in combination with contemporary POC troponin by EMS personnel.

The HART-c study [Citation32] focused on all prehospital patients with suspected cardiac symptoms, not only those with chest pain. Hemodynamically unstable patients were excluded. The main goal was to reduce hospital referrals and interhospital transfers. A newly developed triage platform was introduced where EMS nurses consult cardiologists who are on-call. Both have access to live-streamed patient data from the ambulance, such as vital parameters and (serial) ECGs and real-time regional ED, hospital and cardiac care unit (CCU) capacity. After initial assessment, the EMS nurse and cardiologist agree on whether hospital referral is needed and, if so, which regional hospital is most appropriate. Results from the HART-c study showed a significant decrease in interhospital transfers and a significant increase in patients safely kept at home (11.8% in intervention versus 5.9% in control, odds ratio 2.31 [95% CI: 1.74–3.05]) [Citation33].

In the URGENT trial [Citation14] the HEART score is combined with a finger prick (capillary blood) high-sensitivity POC troponin I measurement (Siemens Atellica VTLi), again with the aim of leaving patients with a low HEART score and negative POC hs-cTn at home without unnecessary hospital referral. A first small study showed promising results. A second randomized controlled trial (NCT04904107) from this study is currently taken place.

The PRESTO study performed in the UK evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of the T-MACS decision aid to rule out an ACS in the ambulance with POC troponin assays. This could allow paramedics to immediately rule out ACS for patients with very low risk and avoid hospital transfers. Besides safely ruling out, this project can also improve the timing of ruling in an ACS, allowing to refer faster to the appropriate hospital and thus facilitate earlier specialist treatment [Citation34]. Results of this study are expected soon.

While several of the above studies examined safety, feasibility and MACE end points, a number of studies also focused on cost–effectiveness. All concluded that improved triage based on risk stratification combined with a POC troponin measurement can lead to substantial cost reduction, decrease overcrowding in EDs and reduce interhospital ambulance transfers [Citation15,Citation35,Citation36].

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin within rapid rule in & rule out algorithms

When hs-cTn tests are available, the ESC recommends the use of a 0h/1h algorithm [Citation4]. Sandoval et al. even advocate to rule out ACS based on a single hs-cTn measurement with assay-specific cut-off values, when the initial ECG is normal and the patients clinical situation is not concerning [Citation37].

If harmonized care is implemented in the acute care chain, it is not unimaginable that in a 0h/1h algorithm, the first determination of hs-cTn will be performed in the prehospital setting. This initial POC hs-cTn measurement (T0), combined with a risk stratification tool, supports prehospital decision-making and decrease hospital referral, but could also significantly decrease observation time in the ED, were only the second hs-cTn measurement (T1) is needed, and thus diminishing overcrowding.

Nowadays reliable and valid POC hs-cTnI devices are available which may further improve the risk stratification in quality and safety. This may result in a modified score of the troponin element of a risk score, with new cut-off values based on the limit of quantitation (LoQ). The LoQ is the lowest concentration, with a 20% coefficient of variation, that can be quantified [Citation37]. Using a modified HEART score, with troponin points based on values of hs-cTn below the limit of quantitation (0 points), between the limit of quantitation and the 99th percentile (1 point) and above the 99th percentile (2 points) the score turned out to be stronger and more reliable with increasing safety and higher sensitivity and negative predictive value in ruling out patient with suspected NSTE-ACS () [Citation38].

Table 3. Cardiac troponin cut-off values within the modified history, electrocardiogram, age, risk factors and troponin score.

Future perspective

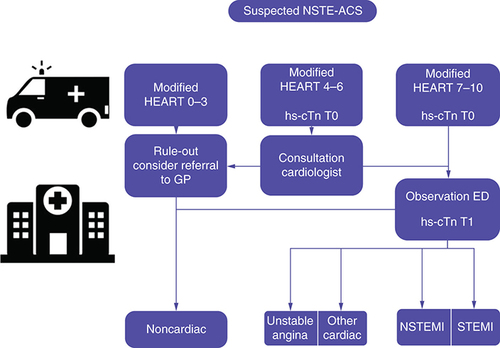

Taken all the evidence and developments into account a new pathway of acute cardiac care should be considered in which prehospital care is integrated into existing in-hospital guidelines and the chain of care is aligned in the process. In this pathway () initial risk stratification with the modified HEART score is performed by EMS personnel, including a hs-cTn measurement on a POC device.

Low risk patients, with a modified HEART score from 0–3, should not be referred to the hospital, unless there is a suspicious anamnesis for either a cardiac or other serious diagnosis. Based on the clinical judgment of the EMS nurse, referral to a GP might be of additional value. It is important to state that the modified HEART score should support the EMS decision, but the score itself is not leading. Consideration of other diagnoses that require further analysis by a GP or in the hospital remains important. In case of any doubt, consultation with a cardiologist should ideally be possible (as in the HART-c study).

Patients with a HEART score >3 are referred to a hospital ED. More research is required to determine whether patients with an intermediate risk score (HEART 4–6) could also be spared from being transported to hospital after consulting a cardiologist. Within this group, with MACE rates between 13% and 20%, it might also be possible, particularly in combination with POC hs-cTn, to make significant improvements. For those patients transferred to the hospital a 0h/1h algorithm should be used, the first blood sample taken in the ambulance serves as T0. To rule in or rule out an ACS, only one more hs-cTn is necessary in the ED (T1), preferably on a similar type of POC device. Further diagnostics can be performed in the meantime.

Such protocol would significantly reduce hospital referrals, decrease observation time at the ED, reduce ED overcrowding, overdiagnosis and hospital admissions. Direct rule in for NSTE-ACS based on a high threshold value for hs-cTn reveals high specificity and positive predictive value [Citation21,Citation39]. Potentially, those patients might be transferred directly to an interventional center, where they can be treated more rapidly in accordance with the ESC Guidelines [Citation4]. More research is required to provide evidence of the added value of this strategy.

ED: Emergency department; GP: General practitioner; HEART: History, ECG, Age, Risk factors and Troponin; hs-cTn: High-sensitivity cardiac troponin; NSTE-ACS: Non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome; NSTEMI: Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Implementation & continuation

When preparing for implementation and also the continuation of new pathways, it is evident that it is important to consider several factors. We mention a few. First of all, training of prehospital professionals will have to be covered. Training in how to determine the HEART score, but also training in the use of the POC devices and especially the interpretation of the results. This will also need to come back with periodic training of the professionals. We recommend in the prehospital setting to use POC devices that are supported by an ISO 15189 accredited laboratory for validation and quality management. Above all, prepare the implementation together with all stakeholders in the chain. After all, the chain, from general practitioner and ambulance to hospital, should be well aligned.

Conclusion

There is growing evidence that prehospital triage of patients suspected for NSTE-ACS is possible with a risk stratification tool combined with a prehospital determination of cardiac troponin without compromising safety. Further development of devices now allows determination of POC hs-cTn as well. This increases the possibilities for prehospital application and combining prehospital care with in-hospital guidelines. In this Special Report, a new care pathway is proposed, in which further harmonization in the chain of acute cardiac care is central. This has the potential to provide the right care at the right place for patients and contribute to a significant reduction in hospital referrals, reduce observation time and overcrowding at emergency departments and hospital admissions.

Introduction

The management of patients presenting with chest pain is challenging, especially in the prehospital setting.

Triage and treatment of patients with chest pain usually starts already in the prehospital setting where guidelines mainly focus on pharmacological treatment and referral to the appropriate hospital while the largest group do not turn out to have acute coronary syndrome (ACS) at all.

Professionals in the prehospital setting can be supported in the triage of chest pain by using a risk stratification tool in combination with a point-of-care determination of cardiac troponin.

ACS management prehospital versus in-hospital

The management for patients suspected of non ST-elevation ACS is well described in guidelines for the in-hospital situation, but the prehospital role in this is lacking.

Cardiac troponin

Cardiac troponin is the most sensitive and specific biomarker of cardiomyocyte injury and can nowadays be determined with excellent diagnostic accuracy on handheld point-of-care devices.

Point-of-care determination of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin, in combination with a risk stratification tool, improves early rule in and rule out of an ACS and therapeutic and referral decisions.

Risk stratification & prehospital studies

The HEART score (history, ECG, age, risk factors and troponin) is a frequently used risk stratification instrument which can be easily and reliable used within all patients presenting with chest pain, also in the prehospital setting.

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin within rapid rule in & rule out algorithm

If high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays are available, rapid decision algorithms are recommended.

Good harmonization in the acute cardiac care chain may allow triage initiated in the prehospital setting to have a direct follow-up in the hospital.

Combined with a risk stratification tool it supports prehospital decision-making and decrease hospital referral, but could also decrease observation time in the emergency department and thus diminishing overcrowding.

Future perspective

A new pathway of acute cardiac care in cooperation with all stakeholders in the acute care chain should be considered.

In this pathway routing of the patients is based on a prehospital modified HEART score with a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurement. In case a patient is referred to the hospital, In case a patient is referred to hospital, they follow the triage that has already been initiated prehospital.

Conclusion

This strategy has the potential to provide the right care at the right place for patients and contribute to a significant reduction in hospital referrals, reduce observation time and overcrowding at emergency departments and hospital admissions.

Author contributions

RT Tolsma and BE Backus drafted the manuscript and all other authors contributed in revising and approving the final version for publication.

Financial disclosure

The authors have no financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Competing interests disclosure

The authors have no competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Ernst NM , DeBoer MJ, Van’ tHof AWet al. Prehospital triage for angiography-guided therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Neth. Heart J., 12(4), 151–156 (2004).

- Van’ t Hof AW , RasoulS, VanDe Wetering Het al. Feasibility and benefit of prehospital diagnosis, triage, and therapy by paramedics only in patients who are candidates for primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J., 151(6), 1255 e1251–e1255 (2006).

- Vester MPM , EindhovenDC, BontenTNet al. Utilization of diagnostic resources and costs in patients with suspected cardiac chest pain. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes, 7(6), 583–590 (2021).

- Byrne RA , RosselloX, CoughlanJJet al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191 (2023) ( Online ahead of print).

- Gulati M , LevyPD, MukherjeeDet al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 144(22), e368–e454 (2021).

- Tolsma RT , Van DongenDN, FokkertMJet al. 48 The pre-hospital HEART score is a strong predictor of MACE in patients with suspected non-STEMI. Eur. Heart J., 38(Suppl. 1), 5 (2017).

- Van Dongen DN , FokkertMJ, TolsmaRTet al. Accuracy of pre-hospital HEART score risk classification using point of care versus high sensitive troponin in suspected NSTE-ACS. Am. J. Emerg. Med., 38(8), 1616–1620 (2020).

- Van Dongen DN , TolsmaRT, FokkertMJet al. Pre-hospital risk assessment in suspected non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: a prospective observational study. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care, 9(Suppl. 1), 5–12 (2020).

- Wibring K , LingmanM, HerlitzJ, AminS, BangA. Prehospital stratification in acute chest pain patient into high risk and low risk by emergency medical service: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 11(4), e044938 (2021).

- Van Der Waarden N , SchottingB, RoyaardsKJ, VlachojannisG, BackusBE. Reliability of the HEART-score in the prehospital setting using point-of-care troponin. Eur. J. Emerg. Med., 29(6), 450–451 (2022).

- Tolsma RT , FokkertMJ, Van DongenDNet al. Referral decisions based on a pre-hospital HEART score in suspected non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: final results of the FamouS Triage study. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care, 11(2), 160–169 (2022).

- Demandt JPA , ZelisJM, KoksAet al. Prehospital risk assessment in patients suspected of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 12(4), e057305 (2022).

- Camaro C , AartsGWA, AdangEMMet al. Rule-out of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome by a single, pre-hospital troponin measurement: a randomized trial. Eur. Heart J., 44(19), 1705–1714 (2023).

- Koper LH , FrenkLDS, MeederJGet al. URGENT 1.5: diagnostic accuracy of the modified HEART score, with fingerstick point-of-care troponin testing, in ruling out acute coronary syndrome. Neth. Heart J., 30(7–8), 360–369 (2022).

- Aarts GWA , VanDer Wulp K, CamaroC. Pre-hospital point-of-care troponin measurement: a clinical example of its additional value. Neth. Heart J., 28(10), 514–519 (2020).

- Sagel D , VlaarPJ, Van RoosmalenRet al. Prehospital risk stratification in patients with chest pain. Emerg. Med. J., 38(11), 814–819 (2021).

- Ishak M , AliD, FokkertMJet al. Fast assessment and management of chest pain patients without ST-elevation in the pre-hospital gateway (FamouS Triage): ruling out a myocardial infarction at home with the modified HEART score. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care, 7(2), 102–110 (2018).

- Stopyra JP , HarperWS, HigginsTJet al. Prehospital modified HEART score predictive of 30-day adverse cardiac events. Prehosp. Disaster Med., 33(1), 58–62 (2018).

- Backus BE , TolsmaRT, BoogersMJ. The new era of chest pain evaluation in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Emerg. Med., 27(4), 243–244 (2020).

- Gunsolus IL , SchulzK, SandovalYet al. Diagnostic performance of a rapid, novel, whole blood, point of care high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I assay for myocardial infarction. Clin. Biochem., 105–106, 70–74 (2022).

- Boeddinghaus J , NestelbergerT, KoechlinLet al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with point-of-care high-sensitivity cardiac Troponin I. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., 75(10), 1111–1124 (2020).

- Rasmussen MB , StengaardC, SorensenJTet al. Predictive value of routine point-of-care cardiac troponin T measurement for prehospital diagnosis and risk-stratification in patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care, 8(4), 299–308 (2019).

- Johannessen TR , AtarD, VallersnesOM, LarstorpACK, MdalaI, HalvorsenS. Comparison of a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T measurement with the HEART score for rapid rule-out of acute myocardial infarction in a primary care emergency setting: a cohort study. BMJ Open, 11(2), e046024 (2021).

- Apple FS , SmithSW, GreensladeJHet al. Single high-sensitivity point of care whole blood cardiac Troponin I measurement to rule out acute myocardial infarction at low risk. Circulation, 146(25), 1918–1929 (2022).

- Chapman AR , HesseK, AndrewsJet al. High-sensitivity cardiac Troponin I and clinical risk scores in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. Circulation, 138(16), 1654–1665 (2018).

- Khand A , FrostF, ChewPet al. Modified heart score improves early, safe discharge for suspected acute coronary syndromes: a prospective cohort study with recalibration of risk scores to undetectable high sensitivity Troponin T limits. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., 69(Suppl. 11), 238 (2017).

- Poldervaart JM , ReitsmaJB, BackusBEet al. Effect of using the HEART score in patients with chest pain in the emergency department: a stepped-wedge, cluster randomized trial. Ann. Int. Med., 166(10), 689–697 (2017).

- Backus BE , SixAJ, KelderJCet al. A prospective validation of the HEART score for chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int. J. Cardiol., 168(3), 2153–2158 (2013).

- Poldervaart JM , LangedijkM, BackusBEet al. Comparison of the GRACE, HEART and TIMI score to predict major adverse cardiac events in chest pain patients at the emergency department. Int. J. Cardiol., 227, 656–661 (2017).

- Aarts GWA , CamaroC, Van GeunsRJet al. Acute rule-out of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome in the (pre)hospital setting by HEART score assessment and a single point-of-care troponin: rationale and design of the ARTICA randomised trial. BMJ Open, 10(2), e034403 (2020).

- Van der Harst P . European Society of Cardiology. A single troponin-based tool to support EMS conyence strategy. https://esc365.escardio.org/presentation/255409

- De Koning E , BierstekerTE, BeeresSet al. Prehospital triage of patients with acute cardiac complaints: study protocol of HART-c, a multicenter prospective study. BMJ Open, 11(2), e041553 (2021).

- De Koning ER , BeeresS, BoschJet al. Improved prehospital triage for acute cardiac care: results from HART-c, a multicenter prospective study. Neth. Heart J., 31(5), 202–209 (2023).

- Alghamdi A , CookE, CarltonEet al. PRe-hospital Evaluation of Sensitive TrOponin (PRESTO) Study: multicenter prospective diagnostic accuracy study protocol. BMJ Open, 9(10), e032834 (2019).

- Van Dongen DN , OttervangerJP, TolsmaRet al. In-hospital healthcare utilization, outcomes, and costs in pre-hospital-adjudicated low-risk chest-pain patients. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy, 17(6), 875–882 (2019).

- Johannessen TR , HalvorsenS, AtarDet al. Cost-effectiveness of a rule-out algorithm of acute myocardial infarction in low-risk patients: emergency primary care versus hospital setting. BMC Health Serv. Res., 22(1), 1274 (2022).

- Sandoval Y , AppleFS, MahlerSAet al. High-sensitivity cardiac Troponin and the 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guidelines for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Acute Chest Pain. Circulation, 146(7), 569–581 (2022).

- Tolsma RT , FokkertMJ, OttervangerJPet al. Consequences of different cut-off values for high-sensitivity cardiac troponin for risk stratification of patients suspected for NSTE-ACS with a modified HEART score. Future Cardiol., 19(10), 497–504 (2023).

- Stengaard C , SorensenJT, RasmussenMB, BotkerMT, PedersenCK, TerkelsenCJ. Prehospital diagnosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Diagnosis (Berl.), 3(4), 155–166 (2016).